Abstract

P-type doping in high Al-content AlGaN alloys is a main challenge for realizing AlGaN-based deep ultraviolet optoelectronics devices. According to the first-principles calculations, Mg activation energy may be reduced so that a high hole concentration can be obtained by introducing nanoscale (AlN)5/(GaN)1 superlattice (SL) in Al0.83Ga0.17N disorder alloy. In this work, experimental evidences were achieved by analyzing Mg doped high Al-content AlGaN alloys and Mg doped AlGaN SLs as well as MgGa δ doped AlGaN SLs. Mg acceptor activation energy was significantly reduced from 0.378 to 0.331 eV by using MgGa δ doping in SLs instead of traditional doping in alloys. This new process was confirmed to be able to realize high p-type doping in high Al-content AlGaN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High Al-content AlGaN alloys are ideal materials for deep ultraviolet (DUV)1 optoelectronic devices due to their large direct band gaps with operating wavelengths from 364 nm down to 200 nm2,3,4,5. The external quantum efficiency (EQE) of AlGaN-based DUV light-emitting diodes (LEDs), however, is as extremely low as 0.1%, which is still a formidable obstacle6,7. N-type AlGaN can be produced relatively easily8,9. The very low p-type doping efficiency in AlGaN hinders the further improvement of AlGaN-based DUV LEDs. The difficulty to realize p-type doping is related to the high acceptor activation energy (EA), the compensation by nitrogen vacancies, the increased hole scattering, and the limited acceptor solubility10,11. For the most widely used p-type dopant of Mg, its EA in AlxGa1−xN increases monotonically with increasing Al-content from 0.17 eV in GaN to 0.51 eV in AlN11,12. This behavior indicates that only a very tiny fraction (~10−9) of Mg dopants can be activated in AlN at room temperature 11. Therefore, decreasing Mg acceptor activation energy is one of the most challenges in AlGaN-based DUV optoelectronic devices.

Great efforts have been devoted to improve p-type conduction in group-III nitrides13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Different from suppressing the charge separation effect in InGaN-based devices, polarization doping has been applied to increase the hole concentration in AlGaN alloys by ionizing Mg acceptor in the polarization field13,14. Alternative acceptor-donor co-doping and non-equilibrium growth with Mg pulse doping and Mg δ-doping have also been developed to reduce the acceptor activation energy, and thus, increase the hole concentration and enhance the p-type conductivity of AlGaN alloys15,16,17,18,19,20. So far, most experiments were focused on the p-type conductions of GaN and low Al-content AlGaN alloys, but the bottlenecks of the p-type doping in high Al-content AlGaN still remain20,21,22.

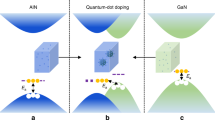

Many works were concentrated on the doping in the superlattices (SLs)23,24,25,26,27,28,29, where a periodic oscillation of the valence band edge was created by the valence band discontinuity and innate polarization fields in Mg-doped AlGaN/GaN SLs, resulting in the accumulation of holes near the valance band edge close to the Fermi energy forming the so-called two-dimensional (2D) hole gases. In our previous work, we have used SiGa δ doping in Al0.6Ga0.4N alloys to increase the n-type carrier density30. Recent theoretical works predicted that the nanoscale (AlN)m/(GaN)n (m > n) SL could convert the valence-band maximum (VBM) from the crystal-field split-off hole to heavy hole band, leading to the increase of the transverse electric (TE) polarized light emission efficiency31,32. The influence of the nearest and next-nearest (NN) atoms on Mg electronic structures in nanoscale (AlN)5/(GaN)1 SL substitution for Al0.83Ga0.17N disorder alloy was theoretically investigated by Zhong et al.1. The results showed that the EA decreases if the NN Ga atom number increased and the Mg-centered tetrahedron volume decreased. In this way, the Mg acceptor activation energy can significantly be reduced to 0.26 eV, very close to that of GaN, in (AlN)5/(GaN)1 SL by MgGa δ-doping1. Recently, improved p-type conductivity was achieved in multidimensional Al0.63Ga0.37N/Al0.51Ga0.49N SLs33. In this work, we use MgGa δ doping in (AlN)m/(GaN)n SLs to study Mg acceptor activation energy, aiming to find a proper way to minimize it in high Al-content AlGaN.

Methods

In this work, traditional Mg doped AlGaN alloys (in which Al, Ga, Mg and N atoms arrived at the substrate at the same time), Mg doped AlGaN SLs and MgGa δ doped AlGaN SLs were grown on c-plane sapphire substrates by using the radio-frequency plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy system (rf-MBE, SVTA 35-V-2). The growth details are shown in Table 1 Sample D1 and D2 were Mg doped AlGaN alloys with traditional doping method. Mg doping was continuously carried out for 30 min. Sample D3 and D4 were Mg doped AlGaN SLs. Mg doping was continuously performed for 10 s at each cycle and the total deposition lasted for 180 cycles. Hence the real Mg doping time was also 30 min. Sample D5 and D6 were MgGa δ doped AlGaN SLs with a cycle period of 15 s for 180 cycles. Although the cycle period of sample D5 and D6 was 15 s, the effective growth time in a cycle was still kept as 10 s and the total effective growth time was also 30 min. For sample D5, the growth process consisted of two loops as shown in Fig. 1. During the growth of AlGaN thin films, the nitrogen flow rate was set at 2.65 sccm under 375 W rf-plasma power. Prior to the growth, nitridation was performed at 810 °C for 10 min under 500 W rf-plasma power with a nitrogen flow rate of 2.65 sccm. AlGaN films were examined by high-resolution x-ray diffraction (HRXRD, Bede D1) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, JEOL JEM 2010 FEF UHR). Ni/Au electrodes (15 nm Ni and 50 nm Au) were made by thermal evaporation with templates of 150 × 150 μm2 in area. Current versus voltage (I-V) characteristics were measured by using a semiconductor device analyzer (Keithley 4200, Keithley Instruments).

Results

Figure 2 shows XRD patterns of AlGaN films grown on sapphire substrates. AlGaN (0002) peaks were found between the GaN (0002) peak at 34.543° and AlN (0002) peak at 36.033°. The Al2O3 (0006) peaks were normalized at 41.700°. The full widths at half maximum (FWHM) of the Mg-doped AlGaN (0002) peaks were around 800 arcsec in alloys and 1000 arcsec in SLs. AlGaN peaks were fitted with Gauss model to get more accurate peak information. According to the alloy crystal parameter formula  and Bragg’s law 2dhklsinθ = nλ as well as hexagonal interplanar distance formula

and Bragg’s law 2dhklsinθ = nλ as well as hexagonal interplanar distance formula  , the compositions of AlxGa1−xN thin films were determined by using standard crystal parameter cGaN of 0.5189 nm and cAIN of 0.4981 nm. In this way, the compositions of all samples from D1 to D6 were Al0.97Ga0.03N, Al0.75Ga0.25N, Al0.79Ga0.21N, Al0.53Ga0.47N, Al0.76Ga0.24N and Al0.47Ga0.53N, respectively. The compositions of (AlN)m/(GaN)n in D3 and D5 nearly matched to the designed value of 4:1, while those in D4 and D6 nearly approached to the designed 1:1.

, the compositions of AlxGa1−xN thin films were determined by using standard crystal parameter cGaN of 0.5189 nm and cAIN of 0.4981 nm. In this way, the compositions of all samples from D1 to D6 were Al0.97Ga0.03N, Al0.75Ga0.25N, Al0.79Ga0.21N, Al0.53Ga0.47N, Al0.76Ga0.24N and Al0.47Ga0.53N, respectively. The compositions of (AlN)m/(GaN)n in D3 and D5 nearly matched to the designed value of 4:1, while those in D4 and D6 nearly approached to the designed 1:1.

As XRD results reveal only the macro compositions of the AlGaN films, the (AlN)m/(GaN)n SLs were confirmed by HRTEM results. Figure 3(a) shows the cross-sectional HRTEM image of AlGaN SLs grown on sapphire in sample D5. The total thickness of AlGaN SLs were about 210 nm. The magnified HRTEM image of AlGaN SLs and the corresponding FFT image are shown in Fig. 3(b) and (c). The growth direction of AlGaN SLs on sapphire was [0002], in agreement with the XRD results. As shown in Fig. 3(c), five extra diffraction spots were obtained along [0002] axis in one unit. The four quinquesection spots were attributed to the (AlN)4/(GaN)1 SLs, indicating that the monolayer SL structure was achieved and NN Ga atom number increased in sample D5. The one bisection spot might be caused by the dislocations. Hence sample D5 was measured to be (AlN)4/(GaN)1 superlattices, achieving the designed (AlN)m/(GaN)n SLs structure with increased NN Ga atom number.

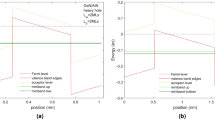

Figure 4 shows the I-V characteristics of sample D4, D5 and D6 at different temperatures. The linear I-V behavior indicated the Ohmic contacts between Ni/Au electrodes and AlGaN films. The good ohmic behavior could be attributed to the formation of p-type NiO34. As for sample D5, the resistances were deduced to be 13.67 GΩ, 5.776 GΩ, 2.090 GΩ, 1.042 GΩ, 547.8 MΩ and 340.3 MΩ at temperatures of 50, 80, 110, 140, 170 and 200 °C, respectively. The insets show the corresponding Arrhenius plot of the resistivity (ρ) versus temperature (T). Since  , the ionization energy (EA) of Mg in AlxGa1−xN in sample D5 was fitted to be 0.331 eV as shown in Fig. 4(b). The same procedures were also performed for other samples. As for the asymmetry I-V curves as shown in Fig. 4(c), EA was calculated separately under positive and negative voltages and then made of an average. The EA for samples D1-D6 were 0.386, 0.378, 0.358, 0.344, 0.331, and 0.311 eV, respectively. The highest EA as 0.386 eV was in sample D1 and the lowest EA as 0.311 eV lied in sample D6, in match with calculated results that high EA in high Al component alloys, and low EA in low Al component SLs.

, the ionization energy (EA) of Mg in AlxGa1−xN in sample D5 was fitted to be 0.331 eV as shown in Fig. 4(b). The same procedures were also performed for other samples. As for the asymmetry I-V curves as shown in Fig. 4(c), EA was calculated separately under positive and negative voltages and then made of an average. The EA for samples D1-D6 were 0.386, 0.378, 0.358, 0.344, 0.331, and 0.311 eV, respectively. The highest EA as 0.386 eV was in sample D1 and the lowest EA as 0.311 eV lied in sample D6, in match with calculated results that high EA in high Al component alloys, and low EA in low Al component SLs.

I-V characteristics of (a) sample D4, (b) sample D5 and (c) sample D6 at different temperatures. The insets show the corresponding Arrhenius plots of the resistivity versus temperature. The ionization energy of Mg in AlGaN in sample D4, D5 and D6 was determined to be 0.344, 0.331 and 0.311 eV, respectively.

Figure 5 shows the dependence of EA on Al composition in AlGaN with three doping methods. Obviously, the EA reaches the lower values in MgGa δ doped AlGaN SLs, the medium in Mg doped SLs and the higher in traditional Mg doped AlGaN alloys. As for Al content around 0.8, the EA decreases from 0.378 to 0.358, then to 0.331 eV by the three methods in turn as Mg doped AlGaN alloys, Mg doped SLs and MgGa δ doped SLs. Hence, Mg acceptor activation energy can be significantly reduced from 0.378 to 0.331 eV by using MgGa δ doping in (AlN)4/(GaN)1 SLs instead of traditional Mg doping in Al0.8Ga0.2N alloys. The difference between the theoretical value (0.26 eV) and the experimental one (0.331 eV) is attributed to two reasons: firstly, the macro function of Mg activation energy in Ga and Al was measured in this experiment while only the Mg activation energy in Ga was calculated to be 0.26 eV; secondly, the as-grown (AlN)4/(GaN)1 SLs were not perfect single crystal with dislocations which might affect the Mg activation energy. Therefore, we have experimentally proved the theoretical prediction that Mg acceptor activation energy can be significantly decreased in (AlN)m/(GaN)n SL1.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have systematically studied Mg doping in high Al-content AlGaN by using different doping methods. For high Al-content AlGaN, Mg acceptor activation energy can be significantly reduced from 0.378 to 0.331 eV by using MgGa δ doping in (AlN)4/(GaN)1 SLs instead of traditional Mg doping in Al0.8Ga0.2N alloys. Our experimental study verifies the prediction of the first-principles calculations1, and provides potential applications in AlGaN-based DUV optoelectronic devices.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, X. et al. Experimental evidences for reducing Mg activation energy in high Al-content AlGaN alloy by MgGa δ doping in (AlN)m/(GaN)n superlattice. Sci. Rep. 7, 44223; doi: 10.1038/srep44223 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Zhong, H. X. et al. Reducing Mg acceptor activation-energy in Al0.83Ga0.17N disorder alloy substituted by nanoscale (AlN)5/(GaN)1 superlattice using MgGa δ-doping: Mg local-structure effect. Sci. Rep. 4, 6710 (2014).

Zhao, S. et al. Aluminum nitride nanowire light emitting diodes: Breaking the fundamental bottleneck of deep ultraviolet light sources. Sci. Rep. 5, 8332 (2015).

Yang, W. et al. High density GaN/AlN quantum dots for deep UV LED with high quantum efficiency and temperature stability. Sci. Rep. 4, 5166 (2014).

Huang, K. et al. Top- and bottom-emission-enhanced electroluminescence of deep-UV light-emitting diodes induced by localized surface plasmons. Sci. Rep. 4, 4380 (2014).

Al Tahtamouni, T. M., Sedhain, A., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Growth and photoluminescence studies of a-plane AlN∕AlxGa1−xN quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 221105 (2007).

Kneissl, M. et al. Advances in group III-nitride-based deep UV light-emitting diode technology. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 26, 014036 (2011).

Gao, N. et al. Surface-plasmon-enhanced deep-UV light emitting diodes based on AlGaN multi-quantum wells. Sci Rep. 2, 816 (2012).

Nakarmi, M. L., Kim, K. H., Zhu, K., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Transport properties of highly conductive n-type Al-rich AlxGa1−xN (x≥0.7). Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 3769 (2004).

Al Tahtamouni, T. M., Sedhain, A., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Si-doped high Al-content AlGaN epilayers with improved quality and conductivity using indium as a surfactant. Appl. Phys. Lett. 9, 092105 (2008).

Yan, Y., Li, J., Wei, S. & Al-Jassim, M. M. Possible approach to overcome the doping asymmetry in wideband gap semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 135506 (2007).

Nam, K. B., Nakarmi, M. L., Li, J., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Mg acceptor level in AlN probed by deep ultraviolet photoluminescence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 878 (2003).

Nakarmi, M. L., Nepal, N., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Photoluminescence studies of impurity transitions in Mg-doped AlGaN alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 091903 (2009).

Simon, J., Protasenko, V., Lian, C., Xing, H. & Jena, D. Polarization-Induced Hole Doping in Wide-Band-Gap Uniaxial Semiconductor Heterostructures. Science 327, 60 (2010).

Gao, L., Xie, F. & Yang, G. Numerical study of polarization-doped AlGaN ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. Superlatt. Microstruct. 71, 1 (2014).

Wu, R. Q. et al. Enhancing hole concentration in AlN by Mg:O codoping: Ab initio study. Phys. Rev. B 77, 073203 (2008).

Aoyagi, Y., Takeuchi, M., Iwai, S. & Hirayama, H. High hole carrier concentration realized by alternative co-doping technique in metal organic chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 112110 (2011).

Aoyagi, Y., Takeuchi, M., Iwai, S. & Hirayama, H. Formation of AlGaN and GaN epitaxial layer with high p-carrier concentration by pulse supply of source gases. AIP Advances 2, 012177 (2012).

Al Tahtamouni, T. M., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Effects of Mg-doped AlN/AlGaN superlattices on properties of p-GaN contact layer and performance of deep ultraviolet light emitting diodes. AIP Advances 4, 047122 (2014).

Nakarmi, M. L., Kim, K. H., Li, J., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Enhanced p-type conduction in GaN and AlGaN by Mg-δ-doping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 3041 (2003).

Chen, Y. et al. High hole concentration in p-type AlGaN by indium-surfactant-assisted Mg-delta doping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 162102 (2015).

Nakarmi, M. L. et al. Electrical and optical properties of Mg-doped Al0.7Ga0.3N alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 092108 (2005).

Kinoshita, T., Obata, T., Yanagi, H. & Inoue, S. I. High p-type conduction in high-Al content Mg-doped AlGaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 012105 (2013).

Schubert, E. F., Grieshaber, W. & Goepfert, I. D. Enhancement of deep acceptor activation in semiconductors by superlattice doping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 3737 (1996).

Kozodoy, P., Hansen, M., DenBaars, S. P. & Mishra, U. K. Enhanced Mg doping efficiency in Al0.2Ga0.8N/GaN superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 3681 (1999).

Goepfert, I. D., Schubert, E. F., Osinsky, a., Norris, P. E. & Faleev, N. N. Experimental and theoretical study of acceptor activation and transport properties in p-type Al x Ga1−x N/GaN superlattices. J. Appl. Phys. 88, 2030 (2000).

Waldron, E. L., Li, Y.-L., Schubert, E. F., Graff, J. W. & Sheu, J. K. Experimental study of perpendicular transport in weakly coupled Al x Ga1−x N/GaN superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 4975 (2003).

Waldron, E. L., Graff, J. W. & Schubert, E. F. Improved mobilities and resistivities in modulation-doped p-type AlGaN/GaN superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 2737 (2001).

Kauser, M. Z., Osinsky, a., Dabiran, a. M. & Chow, P. P. Enhanced vertical transport in p-type AlGaN⁄GaN superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 5275 (2004).

Wang, L. et al. Strain modulation-enhanced Mg acceptor activation efficiency of Al0.14Ga0.86N/GaN superlattices with AlN interlayer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 061110 (2010).

Wang, W. et al. High quality n-type aluminum gallium nitride thin films grown by interrupted deposition and in-situ thermal annealing. Mat. Sci. Semicon. Proc. 30, 512 (2015).

Taniyasu, Y. & Kasu, M. Polarization property of deep-ultraviolet light emission from c-plane AlN/GaN short-period superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 251112 (2011).

Jiang, X.-h. et al. Enhancement of TE polarized light extraction efficiency in nanoscale (AlN)m/(GaN)n(m>n) superlattice substitution for high Al content AlGaN disorder alloy: ultra-thin GaN layer modulation. New J. Phys. 16, 113065 (2014).

Zheng, T. C. et al. Improved p-type conductivity in Al-rich AlGaN using multidimensional Mg-doped superlattices. Sci. Rep. 6, 21897 (2016).

Ho, J. et al. Low-resistance ohmic contacts to p-type GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 1275 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the NSFC under Grant Nos 11574235, 11175135, J1210061 and the MOST China under Grant Nos 2014GB109004. The authors would like to thank Dr. He Zheng, Fan Cao and Ligong Zhao for the technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. carried out the experiments and drafted the manuscript. W.W. participated in the design of the study and performed the analysis. J.L.W. participated in the measurements. H.W. conceived the study and participated in its design. C.L. supervised the overall study and polished the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Wang, W., Wang, J. et al. Experimental evidences for reducing Mg activation energy in high Al-content AlGaN alloy by MgGa δ doping in (AlN)m/(GaN)n superlattice. Sci Rep 7, 44223 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44223

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44223

This article is cited by

-

Progress on AlGaN-based solar-blind ultraviolet photodetectors and focal plane arrays

Light: Science & Applications (2021)

-

Quantum engineering of non-equilibrium efficient p-doping in ultra-wide band-gap nitrides

Light: Science & Applications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.