Abstract

Highly conserved short sequences help identify functional genomic regions and facilitate genomic annotation. We used Salmonella as the model to search the genome for evolutionarily conserved regions and focused on the tetranucleotide sequence CTAG for its potentially important functions. In Salmonella, CTAG is highly conserved across the lineages and large numbers of CTAG-containing short sequences fall in intergenic regions, strongly indicating their biological importance. Computer modeling demonstrated stable stem-loop structures in some of the CTAG-containing intergenic regions, and substitution of a nucleotide of the CTAG sequence would radically rearrange the free energy and disrupt the structure. The postulated degeneration of CTAG takes distinct patterns among Salmonella lineages and provides novel information about genomic divergence and evolution of these bacterial pathogens. Comparison of the vertically and horizontally transmitted genomic segments showed different CTAG distribution landscapes, with the genome amelioration process to remove CTAG taking place inward from both terminals of the horizontally acquired segment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterial genomes may contain highly conserved short sequences that are lineage-specific, such as the tetranucleotide sequence CTAG in Escherichia coli and Salmonella1,2. Genomic regions containing such conserved short sequences carry information about the evolution and phylogenetic divergence of the bacteria, but so far such information, especially that embedded in the intergenic regions, has not been efficiently extracted, due largely to the lack of theoretical or methodological strategies to reveal such conserved sequences. As a result, intergenic regions of the bacterial genomes have been poorly annotated in contrast to genes, which researchers often compare with those of E. coli3 for annotation, taking the advantage that functions of many of the E. coli genes have been validated by molecular biology experiments. Such a situation calls for novel approaches to facilitate genomic annotation, and characterization of conserved short sequences may prove instrumental in the identification of functional intergenic sequences.

For this purpose, we have focused on the identification and characterization of short sequences in the bacterial genome, using representative Salmonella lineages as the models. Previously, we reported that the CTAG-containing endonuclease cleavage sites such as that of XbaI (TCTAGA) are highly conserved4,5. In a recent study, we found that many of such cleavage sites are located in common intergenic regions across Salmonella and E. coli1. This finding strongly suggests the potential importance of such sequences and brings up the hopes that the identification and functional analyses of such genomic regions may facilitate bacterial genome annotation and functional studies. We anticipate that the highly conserved intergenic regions may be involved in gene expression regulation and pathogenic evolution. In the case of Salmonella, more enhanced genome annotation strategies are especially needed for understanding the divergence processes that have created diverse and distinct pathogens from common ancestors.

One of the main reasons for us to use Salmonella as the models in this study is that this genus contains the most widely distributed bacterial lineages known to date, which are genetically highly similar among them but pathogenically each drastically distinct6, with the genetic factors that have made these closely related bacteria different pathogens remaining largely unknown. Since the first isolation of a Salmonella strain from a typhoid patient in 1881, more than 2600 Salmonella lineages, classified as serotypes based on their different combinations of the somatic (O) and flagellar (H) antigens, have been documented7. The genetic similarity among the Salmonella serotypes was revealed by comparison of genome structures in the last century8,9 and genomic sequences since the beginning of this century10,11,12, although these bacteria cause different diseases, from self-limited gastroenteritis (such as S. typhimurium, S. enteritidis, etc.) to potentially fatal systemic infections like typhoid (such as S. typhi)13. The current bacterial taxonomy tends to classify the gastroenteritis-causing S. typhimurium and the typhoid-causing S. typhi into the same subspecies as Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovars Typhimurium and Typhi, respectively, however we and many other authors have continued using the traditional nomenclature to avoid confusion; we explained the rightfulness of treating S. typhimurium and S. typhi as separate species in a recent perspective article14.

Previous studies have shown that the Salmonella lineages that elicit similar disease phenotypes may have evolved by either divergent or convergent processes12. However, whether similar pathogens may use the same set or overlapping sets of genes for the infections remains unclear. Further, very possibly, some elements encoded by intergenic sequences might be involved in the modulation of virulence expression. Complicating this issue is the fact that more than half of the genes in Salmonella genomes still await convincing annotation, and deciphering the seemingly non-coding sequences in the intergenic regions is even more challenging.

In this study, we profiled the CTAG sequences, which are relatively rare in Escherichia coli and Salmonella15, in representative Salmonella serotypes. To evaluate their level of conservation in evolution, we determined their genomic distribution in comparison with E. coli and other bacteria. We hypothesize that it is the potential biological significance of the intergenic CTAG-containing sequences that have made them highly conserved, therefore they survived the elimination process by the Very Short Patch (VSP) repair mechanism2. We ranked the profiled CTAG sequences according to their theoretical importance in function by their levels of evolutionary conservation. As the most highly conserved sequences may retain key functions, we focused on the CTAG sequences that are present in the least annotated intergenic regions across Salmonella and E. coli. Computer modeling demonstrated that, for the CTAG sequences conserved in bacteria across the Enterobacteriaceae genera, substitution of any of the four nucleotides may disrupt the stem-loop structure of the CTAG-containing intergenic sequence, potentially affecting their biological functions. We also documented CTAG sequence degeneration patterns and found that the CTAG sequence decays in serotype-specific ways. Of particular interest, the degeneration processes of CTAG seemed to be current and still going on at different stages in the genome.

Methods

Bacterial strains

Information on all bacterial strains used in this study can be found at the Salmonella Genetic Stock Center (http://www.ucalgary.ca/~kesander/), and the accession numbers of the sequenced genomes can be found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome. We use the traditional Salmonella nomenclature for reasons detailed in a previous publication14.

Construction of phylogenetic trees

We aligned the 16S rDNA sequences of the bacterial strains in comparison using the Clustal X program and constructed the phylogenetic trees by MEGA6 using the Neighbor-Joining algorithm.

General strategies of computer modeling to predict secondary structures of short sequences

The modeling was conducted based on the Free Energy Minimization method16,17,18. As free energy models typically assume that the total free energy of a given secondary structure for a molecule is the sum of independent contributions of adjacent or stacked base pairs in stems, we particularly focused on the stem-loop structures. Specifically, we employed the Vienna RNA Package (http://www.tbi.univie.ac.at/RNA/), which consists of a C code library and several stand-alone programs, including RNAfold. This program reads RNA sequences from standard inputstdin, calculates their minimum free energy (mfe) structure and prints to standard output. The mountain.pl script produces a mountain plot, which is an xy-diagram plotting the number of base pairs enclosing a sequence position. The resulting plot shows three curves (red, black and green, respectively; Fig. 1), with the red one showing two peaks derived from the MFE structure, the black one demonstrating the pairing probabilities, and the green one indicating the positional entropy. Well-defined regions are identified by low entropy. By superimposing several mountain plots, the structures can easily be compared.

To test the reliability of the modeling, we also used the Maximum Expected Accuracy method by the program CONTRAfold19 and predicted the most probable structure and the pseudo-knot-free structures by maximizing the sum of the base-paired and single-stranded nucleotide probabilities, called expected accuracy, where pairing probabilities can be weighted by a specific factor. CONTRAfold uses probabilistic parameters learned from a set of RNA secondary structures to predict base-pair probabilities and then predicts structures using the maximum P (i, j) expected accuracy approach. In this study, we referred to The MaxExpect program (http://rna.urmc.rochester.edu/RNAstructureWeb), which is part of the RNAstructure package by Mathews Lab, University of Rochester Medical Center, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics. To run the programs for the prediction, we used an HPC Cluster based on Ubuntu 14.04.2 LTS (Trusty), employing the Sun Grid Engine 6.2u5–7.3 amd64 as queue manager and scheduler to accept jobs. We ran the programs on the cluster in “trivial parallel computing” way and obtained the results from RNAfold v. 2.19 and MaxExpect v. 5.6 linked to Perl v.5.18.2. Throughout the modeling, we used both strategies to crosscheck each other’s performance and evaluate the quality of the obtained predictions.

Using the RNAfold program to model the structure

We used two scripts, mountain.pl and relplot.pl, We used two scripts, mountain.pl and relplot.pl, which are part of the core routines on-board with the Vienna RNA Package (www.tbi.univie.ac.at/RNA/), with the former for predicting pair probabilities within the equilibrium ensemble and the latter for producing a diagram of the predicted structure containing also information about probability. The Perl script relplot.pl adds reliability information to a RNA secondary structure plot and computes a well-definedness measure, which we call “positional entropy” (Fig. 1).

Secondary structure prediction by the MEA approach

Using the MaxExpect program, we executed the following command: MaxExpect –sequence LT2-SpeI.fasta LT2-SpeI.out –gamma 1 –percent 10 –structures 20 –window 3″. This will generate a file name containing information about the predicted structure.

Illustration of CTAG frequency and landscape on genomic sequences

The frequency of the CTAG sequence was analyzed using our own Perl scripts. To profile the CTAG sequences, we first looked for the positions of all CTAG and then extended the analysis to 50 bp of the genomic sequence both up- and down-stream of the CTAG. We used this 104 bp sequence as query to search in BLAST db (like subject sequence). To illustrate the CTAG frequency on the genomic sequence, we showed the numbers of the tetranucleotide per 10 kb window.

Determining the level of sequence conservation

To determine how a given sequence is conserved across different bacteria, we searched it against the NCBI databases by the BLAST service and ranked the level of conservation by the set of parameters including Max and Total scores, E-values and sequence coverage and percent identity. In the case of the inter-lpp-pykF sequence, we used the sequence as query in the search against the database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome) that contains all published genomes of Enterobacteriaceae family.

Results

Profiling the CTAG sequence in bacterial genomes

The tetranucleotide sequence CTAG is remarkably under-abundant in E. coli and Salmonella as previously evidenced by the relatively small numbers of endonuclease cleavage sites containing CTAG such as XbaI (TCTAGA), BlnI or AvrII (CCTAGG), and SpeI (ACTAGT)5,15,20, a phenomenon of biased codon usage intensively studied in E. coli21,22. E. coli and closely related bacteria contain the Very Short Patch repair system, which tends to eliminate CTAG where possible in the genome2,23. To quantitatively validate the scarcity of the CTAG sequence in Salmonella and E. coli, we profiled the tetranucleotides consisting of one each of C, T, A and G ordered randomly in the genome by the formula of:

In S. typhimurium LT2, p(C), p(T), p(A) and p(G) are 0.26, 0.24, 0.24 and 0.2610,22, respectively, and the frequency of a random combination of C, T, A and G comes to 0.00389376, which would lead to an estimated number of a random combination of C, T, A and G to be 18914 in the genome of S. typhimurium LT2, which is 4857432 bp. When we actually profiled the tetranucleotide sequences consisting of one each of C, T, A and G in S. typhimurium LT2 and representative strains of S. typhi, S. paratyphi A, B, C, and S. gallinarum in comparison with E. coli K12, we found that the majority of the combinations have numbers greater than twelve thousand in all Salmonella genomes analyzed and the numbers of many of them are close to the estimated 18914 (Table 1), e.g., CAGT (18347), TGAC (19229), ACTG (18472) or GATC (19168).

To test the postulation that the CTAG sequence scarcity seen in Salmonella1 is not a general feature of bacteria at large, we screened sequenced strains of phylogenetically diverse bacteria to document the number of the CTAG sequence and determine its frequency per kb genome (Supplementary Table 1). We found that the CTAG sequence frequency varies widely among the bacteria, from as low as 0.023 per kb in Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii DSM 11347 (Phylum: Nitrospira, Class: Nitrospira, Order: Nitrospirales, Family: Nitrospiraceae; Chromosome 1, GC percentage: 34%) to as high as 3.933 per kb in Thermobaculum terrenum ATCC BAA-798 (Thermobaculum; GC percentage: 48%). E. coli K12 and S. typhimurium LT2 had a CTAG sequence frequency of 0.191 and 0.175 per kb, respectively. It is worth noting that bacteria with CTAG sequence frequencies lower than those of E. coli and Salmonella were seen in both low and high GC categories, demonstrating that the CTAG sequence frequency is not correlated with GC contents. Even within a narrow range of GC compositions, such as GC percentages of >45 and <=55%, which cover those of E. coli and Salmonella (around 51–52%), CTAG sequence frequencies vary remarkably, e.g., from 0.095 per kb in Prosthecochloris aestuarii DSM 271 (GC 50%) to 3.933 per kb in T. terrenum ATCC BAA-798 (GC 48%). Additionally, at the level of phyla, bacteria having very different GC contents and CTAG sequence frequencies are mixed without a noticeable phylogenetic tendency. For example, bacteria as closely related as Aminobacterium colombiense DSM 12261 and Thermanaerovibrio acidaminovorans DSM 6589 may have GC compositions as different as 45% and 64%, and CTAG sequence frequencies as different as as 0.988 and 0.684 per kb, respectively (see arrows in Fig. 2A, and Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, at the highest evolutionary branches, bacteria do not exhibit phylogenetic tendencies of CTAG frequency or GC content.

(A) Bacterial strains representing a wide range of phyla; color categories for GC percentages: black, GC up to 45%; red, GC 46–55%; blue, GC >55% (see Supplementary Table 1). (B) Bacterial strains representing main branches of the Proteobacteria Phylum; purple color indicates bacteria that had lowest CTAG frequencies among the strains compared (see Supplementary Table 2). (C) Bacterial strains representing main branches of the Gammaproteobacteria Class; orange color indicates bacteria that had lowest CTAG frequencies among the strains compared (see Supplementary Table 3).

Within the Proteobacteria Phylum, bacteria among different Classes have a much narrower range of GC compositions, i.e., from 45 to 55%, but their CTAG sequence frequencies still vary broadly, from 0.125 to 4.590 per kb (Supplementary Table 2), demonstrating that low CTAG sequence frequencies are not common either within the Proteobacteria branch. Of interest, bacteria with lower CTAG frequencies tended to cluster to the Gammaproteobacteria Class, which contains the Enterobacteriaceae including the Genera Salmonella and Escherichia (Fig. 2B). When we focused on representative bacteria among the Gammaproteobacteria branches, we found that bacteria with low CTAG frequencies, such as Salmonella and Escherichia, where the CTAG frequencies are around 0.2 per kb or lower, mostly belong to the Enterobacteriaceae Family (Fig. 2C), although many Enterobacteriaceae bacteria had much higher CTAG frequencies, e.g., >0.7 per kb in Yersinia (Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, CTAG frequency as low as those of Salmonella and Escherichia is not a general feature of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae Family but is common only to Salmonella, Escherichia and their close relatives (Table 2).

Evolutionary implications of the CTAG sequence

Assuming that the common ancestor of Salmonella and E. coli had a much higher frequency of CTAG 200 million years back in evolution, one would anticipate seeing different patterns of the degeneration process of the CTAG sequence among the descendants of the assumed ancestor. In Salmonella, all serotypes have diverged from their ancestors during adaptation to their specific niches under distinct selection pressures. To look into the hypothesized degeneration patterns of the CTAG sequence in different lineages of the bacteria, we profiled CTAG and those deemed homologous to CTAG but with one or two of the four nucleotides replaced by other nucleotides in representative Salmonella strains and found lineage-specific patterns of the degeneration. For example, the CTAG in gene yiaE is conserved in S. typhimurium and S. heidelberg but is degenerated to CTGG in the other Salmonella lineages compared; similarly, the CTAG between genes yjjY and lasT is conserved in most analyzed Salmonella lineages except S. heidelberg, where this tetranucleotide is degenerated to ATAG (Table 3). Overall, each analyzed Salmonella lineage has a distinct pattern of CTAG degeneration, reflected by “signature CTAG degeneracies” such as the ATAG between genes yjjY and lasT in S. heidelberg or combinations of specific CTAG degeneracies, which are present in all strains of a given Salmonella lineage (lineage-specific CTAG degeneration pattern; Supplementary Table 4). For instance, all eight strains of S. typhimurium analyzed in this study have a common pattern and all three strains of S. typhi have another pattern (e.g., the sequence CTAG at the genomic location 2948212–2948215 of S. typhimurium LT2 and all other analyzed Salmonella strains is conserved except S. typhi, in which the sequence is CTAT; Supplementary Table 4). Interestingly, many degenerated sequences are common to several bacterial lineages (e.g., CTAG in cdsA of S. typhimurium strain D23580 is CTGG in all other Salmonella strains compared here including those of S. bongori). Among the degenerated forms, CTGG is the most common degenerated sequence across all bacterial lineages compared throughout the genome, and many other degenerated forms, such as CTCG, are also conserved in certain locations, both reflecting a tendency of preferred nucleotide composition in the amelioration process. We anticipated that comparison of similar and dissimilar CTAG degeneration patterns among the Salmonella lineages may lead to novel discoveries about the divergence and evolution of the diverse pathogens originating from a common ancestor.

Differential levels of evolutionary conservation of the CTAG sequence

We postulated that most ancestral CTAG sequences were degenerated in evolution and became unrecognizable by sequence and this postulation is at least partly supported by the results in Supplementary Table 4, in which the degeneration follows a phylogenetic trend among the bacteria. Based on this finding, we ranked the existing CTAG sequences according to their range of prevalence across bacteria of different taxonomic ranks (e.g., within a bacterial lineage, across different lineages within a genus, or between different genera) and divided them into three levels of conservation: level 1, conserved in Salmonella, as represented by Salmonella subgroup I and V strains, and E. coli, represented by strain K12 MG1655 (Table 4); level 2, conserved among Salmonella but not with E. coli; and level 3, conserved among only Salmonella subgroup I strains; genomic locations of CTAG conserved at the three levels are summarized in Supplementary Table 5.

Hypothesizing that the most highly conserved sequences may retain biological functions across the bacteria that contain them, we focused on the level 1 CTAG sequences in the least annotated intergenic regions of Salmonella in comparison with E. coli. Although intergenic sequences may be involved in replicating the genome, coordinating the expression of other functionalities, mediating recombination24, etc., most intergenic sequences are known for little more than insulating the genes. Since the CTAG profiles of different bacterial lineages, such as S. typhi vs S. typhimurium, may reflect differential selection pressures on specific nucleotides as suggested by phylogenetic analyses described above, we focused on the CTAG sequences in representative Salmonella lineages and E. coli as well as some more distantly related bacteria.

One of the intergenic regions, inter-lpp-pykF between genes lpp and pykF (Fig. 3A), is conserved among bacteria of Salmonella, the E. coli complex (including E. coli and Shigella), Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Yersinia, Citrobacter, Cronobacter, Edwardsiella, Erwinia, Pantoea, Pectobacterium, Rahnella, Serratia, Shimwellia, Sodalis, Dickeya, etc (Supplementary Table 6). The high level of conservation of this intergenic region suggests that this segment might be functionally important and may form some conformational structure for a certain biological function.

(A) Location of lpp, the intergenic region and pykF, with the umbers at the bottom indicating the start and end nucleotides of genes lpp and pykF and the red vertical line indicating the location of CTAG (start and end nucleotides in the brackets); (B) Predicted stem-loop structure; (C) Changed structure when C in the CT(U)AG sequence is substituted by U. The positional entropy is coded by hues ranging from red (low entropy, well-defined) via green to blue and violet (high entropy, ill-defined) Predicted.

Structure prediction of the highly conserved CTAG-containing intergenic sequences

We conducted computer modeling on inter-lpp-pykF and some other intergenic sequences that contain CTAG for further characterization using the Free Energy Minimization method16,17,18, which is widely used for RNA secondary structure prediction based on empirical free energy change parameters derived from experiments. This thermodynamic model assumes that an RNA molecule folds into a structure that has the minimum free energy out of the exponentially increasing possibilities with the growth of lengths of the molecule. As exemplified by the analysis of inter-lpp-pykF, we conducted the modeling and predicted a stem-loop structure using services available at http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi (Fig. 3B). As demonstrated by the substitution of C with U, a base change would dramatically make the free energy re-distributed among the nucleotides (Fig. 3C; compare the change of nucleotide colors) and disrupt the stem-loop structure. Note in Fig. 3C that, even if the position correlation between U and G is the same as C and G before the substitution of C by U, the structure shown on Fig. 3B (before the substitution of C by U) becomes highly unstable (Fig. 3C, after the substitution of C by U) as judged by the changed topology and the radical changes in free energy on every nucleotide. The bioinformatics prediction and biological significance need to be validated by mutational experiments.

Continuing nucleotide refinement of the Salmonella genome to expel the CTAG tetranucleotide sequence – trend of degeneration

The differential numbers and distinct distributions of the CTAG sequence on the genomes among different Salmonella lineages and their degeneration patterns led us to postulate a continuing nucleotide amelioration tendency of the Salmonella genome to expel this tetranucleotide sequence.

We observed a common phenomenon that more-recently diverged Salmonella lineages tend to have greater numbers of the CTAG sequence. For example, S. typhi, which appeared only about 35–50 thousand years ago25, has 1025 CTAG sequences compared to 850 in S. typhimurium or 885 in E. coli, which have diverged millions of years prior to S. typhi in evolution26,27,28. This is mostly because of the newly acquired genomic regions, which were probably not affected by the Very Short Patch repair system before integration to the Salmonella genome.

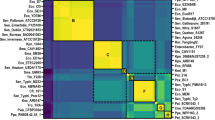

We postulated that analysis of the newly acquired genomic regions may provide a snapshot of the possible scenarios of CTAG degeneration in the Salmonella genome. To look into this postulation, we conducted systematic comparative analyses on two selected S. heidelberg strains, B18229 and SL47630, which have several large genomic insertions present in one but not in the other strain, and profiled the CTAG sequences. We first confirmed that S. heidelberg B182 and S. heidelberg SL476 belong to the same Salmonella natural cluster (as opposed to those of polyphyletic Salmonella serotypes like S. paratyphi B) based on their common genomic features31, and then compared their genomes for the numbers and distributions of the CTAG sequence. We found that for most of the genomes, the two bacterial strains have nearly identical CTAG profiles, with most of the differences being seen only in the laterally acquired DNA segments. Among the genomic insertions present only in S. heidelberg SL476 but not in B182 are Insertions 1 and 2 (marked Insertions 1 and 2, respectively, in Panel A and shown in red color in Panel B, Fig. 4). As anticipated, both insertions have much more densely distributed CTAG sequences than the vertically transmitted genome (the core genome). S. heidelberg SL476 had 108 more CTAG sequences than S. heidelberg B182, most of which (97 out of the 108) were located in the two largest insertions (Insertions 1 and 2; Fig. 4), where we also found many tetranucleotide sequences with one degeneracy. We are inclined to believe that many of tetranucleotide with 75% similarity to CTAG might be the degeneration products of CTAG, but this postulation remains to be validated using homologous DNA segments/sequences from diverse bacteria. The CTAG sequences within each of Insertions 1 and 2 tended to be more densely distributed toward the middle part of the insertions than the upstream- and downstream parts (Fig. 4). To see if this phenomenon might reflect a fact that Salmonella may tend to expel the CTAG sequences in a DNA segment by starting the process from two ends toward the center of the laterally acquired DNA segment, we profiled their CTAG sequence frequencies (Table 5). Notably, these two insertions seemed to be in different stages of the nucleotide amelioration process to degenerate the CTAG sequences since the time when they became incorporated into a Salmonella genome, as judged by the comparison of their calculated and profiled numbers of CTAG (Table 5). S. heidelberg SL476 has 833 CTAG sequences in the core genome, a number that is very similar to that of S. heidelberg B182 (830) and other Salmonella and E. coli strains (such as 850 in S. typhimurium LT2 and 885 in E. coli K12; see Table 1). Whereas Insertion 1 has more than eight time greater density of the CTAG sequences than the core genome, Insertion 2 has half of the density as in Insertion 1 (Table 6), suggesting that Insertion 2 has been in the genome for a much longer time than Insertion 1 to degenerate the CTAG sequences. Additionally, the greater number of CTAG sequences in Insertion 1 than in Insertion 2 is mostly in the middle part of the 41.6 kb insertion, prompting one to believe that the genomic process of degenerating the CTAG sequences had taken place inward from both terminals of the laterally acquired segment, which is illustrated in Fig. 4, where the CTAG sequences have a normal distribution in Insertion 1, but the distribution in Insertion 2 is already similar to that of the core genome. Further scrutiny of the genomic nucleotide composition refinement processes will provide novel information on bacterial genomic evolution that leads to the creation of diverse and distinct pathogens.

(A) Whole genome alignment to show the two largest insertions in SL476 but not B182; (B) Distribution patterns of CTAG inside insertions 1 and 2. The red color indicates the regions of the insertions, with the start and end positions marked in both insertions, and black color indicates the up- and down-stream genomic sequences.

Discussions

To reveal evolutionarily conserved intergenic regions for analyses of their potential functions, we previously profiled the XbaI cleavage site, which is a hexanucleotide sequence containing the tetranucleotide sequence CTAG, in representative Salmonella serotypes and demonstrated that the XbaI cleavage patterns are serotype-specific and so could be used to delineate Salmonella into natural genetic clusters1. Of special significance, many of the profiled XbaI cleavage sites fell in intergenic regions, indicating potential biological importance of these sequences, but their functions remain largely unknown. As profiling the XbaI cleavage site TCTAGA could sample only a subset of the sequences that contain the highly conserved CTAG tetranucleotides2, in this study we documented all CTAG sequences of the genome in representative Salmonella lineages in comparison with E. coli.

Overall, we found that the CTAG sequence is more than 20 times rarer than what would be estimated for a random tetranucleotide sequence consisting of one each of C, T, A and G. Most existing CTAG sequences, except those acquired relatively recently through lateral transfer, are conserved at a certain level: within a Salmonella serotype, among different serotypes of Salmonella subgroup I, across the Salmonella subgroups such as I and V, between Salmonella and E. coli or even more distantly related bacteria, such as CTAG in the inter-lpp-pykF region, which is conserved in bacteria across most genera of the Enterobacteriaceae family (See Supplementary Table 6). We believe that although many of the existing CTAG sequences in the Salmonella genomes may still be in the degenerating process, some of them will stay unchanged in the genomes due to their sequence importance. As such, the comparison of the CTAG degeneration patterns among different bacterial lineages should be a reasonably effective way to reveal hitherto unknown functional genomic regions according to their levels of evolutionary conservation. Computer modeling in this study supported this assumption, demonstrating that substituting any of the tetranucleotides C, T, A or G at highly conserved genomic regions like inter-lpp-pykF would disrupt the stem-loop structure (see Fig. 3).

The CTAG profiles (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5) and their degeneration patterns (each lineage having a specific degeneration pattern; Supplementary Table 4) are unique to each of the Salmonella serotypes analyzed in this study as a consequence of natural selection during the adaptation of the bacteria to a given niche, e.g., a particular host. In fact, the differential levels of conservation among the existing (and very rare) CTAG sequences at different genomic locations (See Table 2 and Supplementary Table 5) should reflect their functional importance and may lead to the discovery of motifs for gene expression regulation or other biological functions. We anticipate that other bacteria may have similarly under-abundant short sequences in the genome, profiling and analysis of which may facilitate the studies of genomic evolution and biological divergence of the bacteria.

One finding of special interest in this study is that the CTAG sequences in a relatively recent insertion have a normal distribution with a typical peak in the middle of the inserted DNA segment. This phenomenon reflects a way that the genome takes to “treat” an incoming DNA segment: if not treating it as a parasite or something useless, the genome may accept it and in time modify it according to the general genomic environment. The “modification” or amelioration process may take place inward from both terminals of the horizontally acquired segment. Detailed analyses of the processes may help in understanding the biological meaning of differential codon usages in different organisms, in correlating natural selection pressure to a particular niche of the bacteria, and in uncovering novel mechanisms of genomic regulation and evolution by the recognition of highly conserved short sequences and their functions.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tang, L. et al. Conserved intergenic sequences revealed by CTAG-profiling in Salmonella: thermodynamic modeling for function prediction. Sci. Rep. 7, 43565; doi: 10.1038/srep43565 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Tang, L. et al. CTAG-containing cleavage site profiling to delineate Salmonella into natural clusters. PLoS One 9, e103388, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103388 PONE-D-14-06722 [pii] (2014).

Bhagwat, A. S. & McClelland, M. DNA mismatch correction by Very Short Patch repair may have altered the abundance of oligonucleotides in the E. coli genome. Nucleic Acids Res 20, 1663–1668 (1992).

Blattner, F. R. et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science (New York, N.Y) 277, 1453–1474 (1997).

Liu, S. L., Hessel, A. & Sanderson, K. E. The XbaI-BlnI-CeuI genomic cleavage map of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 determined by double digestion, end labelling, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Journal of bacteriology 175, 4104–4120 (1993).

Liu, S. L. & Sanderson, K. E. I-CeuI reveals conservation of the genome of independent strains of Salmonella typhimurium. Journal of bacteriology 177, 3355–3357 (1995).

Popoff, M. Y. & Le Minor, L. E. In Bergey’s Mannual of Systematic Bacteriology Vol. 2 (eds Brenner, D. J., Krieg, N. R. & Stanley, J. T. ) 764–799 (Springer, 2005).

Popoff, M. Y., Bockemuhl, J. & Gheesling, L. L. Supplement 2002 (no. 46) to the Kauffmann-White scheme. Research in microbiology 155, 568–570 (2004).

Liu, S. L., Hessel, A. & Sanderson, K. E. Genomic mapping with I-Ceu I, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90, 6874–6878 (1993).

Liu, S. L., Schryvers, A. B., Sanderson, K. E. & Johnston, R. N. Bacterial phylogenetic clusters revealed by genome structure. Journal of bacteriology 181, 6747–6755 (1999).

McClelland, M. et al. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413, 852–856 (2001).

Parkhill, J. et al. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature 413, 848–852 (2001).

Liu, W. Q. et al. Salmonella paratyphi C: genetic divergence from Salmonella choleraesuis and pathogenic convergence with Salmonella typhi. PLoS One 4, e4510, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004510 (2009).

Parry, C. M., Hien, T. T., Dougan, G., White, N. J. & Farrar, J. J. Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med 347, 1770–1782 (2002).

Tang, L. & Liu, S. L. The 3Cs provide a novel concept of bacterial species: messages from the genome as illustrated by Salmonella. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 101, 67–72, doi: 10.1007/s10482-011-9680-0 (2012).

Liu, S. L. & Sanderson, K. E. A physical map of the Salmonella typhimurium LT2 genome made by using XbaI analysis. Journal of bacteriology 174, 1662–1672 (1992).

Gultyaev, A. P., van Batenburg, F. H. & Pleij, C. W. The computer simulation of RNA folding pathways using a genetic algorithm. Journal of molecular biology 250, 37–51, doi: S0022-2836(85)70356-7 [pii] 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0356 (1995).

Zuker, M. & Stiegler, P. Optimal computer folding of large RNA sequences using thermodynamics and auxiliary information. Nucleic Acids Res 9, 133–148 (1981).

Mathews, D. H., Sabina, J., Zuker, M. & Turner, D. H. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. Journal of molecular biology 288, 911–940, doi: S0022-2836(99)92700-6 [pii]10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700 (1999).

Do, C. B., Woods, D. A. & Batzoglou, S. CONTRAfold: RNA secondary structure prediction without physics-based models. Bioinformatics 22, e90–98, doi: 22/14/e90 [pii]10.1093/bioinformatics/btl246 (2006).

Perkins, J. D., Heath, J. D., Sharma, B. R. & Weinstock, G. M. XbaI and BlnI genomic cleavage maps of Escherichia coli K-12 strain MG1655 and comparative analysis of other strains. Journal of molecular biology 232, 419–445, doi: S0022-2836(83)71401-4 [pii]10.1006/jmbi.1993.1401 (1993).

Phillips, G. J., Arnold, J. & Ivarie, R. The effect of codon usage on the oligonucleotide composition of the E. coli genome and identification of over- and underrepresented sequences by Markov chain analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 15, 2627–2638 (1987).

Phillips, G. J., Arnold, J. & Ivarie, R. Mono- through hexanucleotide composition of the Escherichia coli genome: a Markov chain analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 15, 2611–2626 (1987).

Lieb, M. Specific mismatch correction in bacteriophage lambda crosses by very short patch repair. Mol Gen Genet 191, 118–125 (1983).

Alokam, S., Liu, S. L., Said, K. & Sanderson, K. E. Inversions over the terminus region in Salmonella and Escherichia coli: IS200s as the sites of homologous recombination inverting the chromosome of Salmonella enterica serovar typhi. Journal of bacteriology 184, 6190–6197 (2002).

Kidgell, C. et al. Salmonella typhi, the causative agent of typhoid fever, is approximately 50,000 years old. Infect Genet Evol 2, 39–45 (2002).

Ochman, H. & Wilson, A. C. Evolution in bacteria: evidence for a universal substitution rate in cellular genomes. Journal of molecular evolution 26, 74–86 (1987).

Doolittle, R. F., Feng, D. F., Tsang, S., Cho, G. & Little, E. Determining divergence times of the major kingdoms of living organisms with a protein clock. Science (New York, N.Y) 271, 470–477 (1996).

Feng, D. F., Cho, G. & Doolittle, R. F. Determining divergence times with a protein clock: update and reevaluation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 13028–13033 (1997).

Le Bars, H., Bousarghin, L., Bonnaure-Mallet, M., Jolivet-Gougeon, A. & Barloy-Hubler, F. Complete genome sequence of the strong mutator Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Heidelberg strain B182. Journal of bacteriology 194, 3537–3538, doi: 10.1128/JB.00498-12194/13/3537 [pii] (2012).

Fricke, W. F. et al. Comparative genomics of 28 Salmonella enterica isolates: evidence for CRISPR-mediated adaptive sublineage evolution. Journal of bacteriology 193, 3556–3568, doi: 10.1128/JB.00297-11JB.00297-11 [pii] (2011).

Liu, S. L., Hessel, A., Cheng, H. Y. & Sanderson, K. E. The XbaI-BlnI-CeuI genomic cleavage map of Salmonella paratyphi B. Journal of bacteriology 176, 1014–1024 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Heilongjiang Innovation Endowment Award for graduate studies (YJSCX2012-197HLJ), a grant of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC31600001), an Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (AIHS) Postdoctoral Fellowship of Canada, and a National Postdoctoral Fellowship of China to LT; a Heilongjiang Innovation Endowment Award for graduate studies (YJSCX2012-214HLJ) to YJZ, and grants of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC81030029, 81271786, 81671980) to SLL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.T. participated in the designing of the study, carried out the experimental work and conducted genomic sequence analyses; S.L.Z., E.M., X.F. and Y.J.Z. were involved in genomic sequence analyses and CTAG-profiling; Y.G.L., Z.G., R.N.J. and G.R.L. participated in data analysis and discussions. S.L.L. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, L., Zhu, S., Mastriani, E. et al. Conserved intergenic sequences revealed by CTAG-profiling in Salmonella: thermodynamic modeling for function prediction. Sci Rep 7, 43565 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43565

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43565

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.