Abstract

Natural anion channelrhodopsins (ACRs) discovered in the cryptophyte alga Guillardia theta generate large hyperpolarizing currents at membrane potentials above the Nernst equilibrium potential for Cl− and thus can be used as efficient inhibitory tools for optogenetics. We have identified and characterized new ACR homologs in different cryptophyte species, showing that all of them are anion-selective, and thus expanded this protein family to 20 functionally confirmed members. Sequence comparison of natural ACRs and engineered Cl−-conducting mutants of cation channelrhodopsins (CCRs) showed radical differences in their anion selectivity filters. In particular, the Glu90 residue in channelrhodopsin 2, which needed to be mutated to a neutral or alkaline residue to confer anion selectivity to CCRs, is nevertheless conserved in all of the ACRs identified. The new ACRs showed a large variation of the amplitude, kinetics, and spectral sensitivity of their photocurrents. A notable variant, designated “ZipACR”, is particularly promising for inhibitory optogenetics because of its combination of larger current amplitudes than those of previously reported ACRs and an unprecedentedly fast conductance cycle (current half-decay time 2–4 ms depending on voltage). ZipACR expressed in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons enabled precise photoinhibition of individual spikes in trains of up to 50 Hz frequency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Versatile control of the membrane potential in optogenetic studies requires both depolarizing and hyperpolarizing tools. Cation channelrhodopsins from green (chlorophyte) algae (CCRs) are widely used to depolarize the membrane and stimulate neuronal activity1. Hyperpolarization of the membrane and inhibition of neuronal firing by light was first achieved with rhodopsin ion pumps2,3. However, these molecules transport only one charge per absorbed photon, which intrinsically limits their efficiency. They have been successfully used to silence neurons in live animals, but have required high-density expression and intense light (10–20 mW/mm24,5,6). To create better inhibitory tools, CCRs were engineered by mutagenesis to conduct Cl− 7,8,9,10. The latest version of the fast mutants, iC++, permits inhibition of evoked neuronal spiking at higher injected currents than the Cl− pump eNpHR3.0 (enhanced Natronomonas pharaonis halorhodopsin version 3.0)10. The light sensitivity of the Cl−-conducting CCR mutants was further increased by an additional mutation that extends the photocycle duration7,8. The slow mutants can be switched off with red light to improve temporal control of inhibition10, but this photochromicity does not eliminate the need for a long illumination to reach the maximal current amplitude.

Recently discovered natural anion channelrhodopsins (ACRs) from the cryptophyte alga Guillardia theta have fast photocycles and 10,000-fold higher sensitivity than previously used fast silencing tools11. ACR expression in excitable cells allowed specific and robust inhibition of several behavioral responses in live Drosophila at light intensities much lower than those required with eNpHR12. Much more efficient inhibition of action potentials by ACRs than by the proton pump archaeorhodopsin-3 (Arch) at the unperturbed transmembrane Cl− gradient has been demonstrated by extracellular recording from cultured rat ventricular cardiomyocytes13. A homologous protein (PsuACR1) from another cryptophyte, Proteomonas sulcata, also showed anion selectivity14,15, indicating that ACRs are not confined to a single species.

Here we report the identification of new ACR homologs in the transcriptomes of diverse cryptophyte species and electrophysiological analysis of those that produced photocurrents when expressed in cultured mammalian cells. All exhibited anion selectivity, as did the first discovered G. theta ACRs (GtACRs). Sequence alignment of 20 functionally confirmed ACRs shows that the naturally evolved anion conductance has a different structural basis than that created in engineered Cl−-conducting mutants of CCRs. The new natural ACRs demonstrated large variation of their spectral and kinetic properties.

Earlier reported ACRs are appealing either for their large (GtACRs) or relatively fast-decaying (PsuACR1) photocurrents. One of the new ACRs, named PsuACR_973 or “ZipACR” for its fast kinetics, excels in both of these characteristics, being superior to PsuACR1 in its current decay rate and to GtACRs in its current amplitude. In addition, its spectral sensitivity is more red-shifted than that of GtACR2 previously used to suppress neuronal firing. ZipACR expression in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons enabled selective inhibition of individual spikes in neurons firing at 50 Hz, the upper frequency limit for regular spiking in this neuronal type16.

Results

Sequences of the new ACR homologs

To identify transcripts encoding proteins homologous to earlier known ACRs from G. theta11 and P. sulcata14 we searched algal transcriptomes generated by the Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP)17 and 1,000 Plants Project (1KP)18. Of all algal groups, ACR homologs were found only in cryptophytes; Supplementary Table S1 contains a list of analyzed cryptophyte species, their habitats and the output of the search. No ACR homologs were found in freshwater species, but only a small number of such have been analyzed. We synthesized mammalian codon-adapted versions of the seven-transmembrane-helix domains of ACR homologs, the protein alignment of which is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Usually, the first letters of the genus and species names are used in abbreviated rhodopsin names, e.g. Gt for G. theta, and we followed this convention when possible. However, because one Geminigera strain and two Rhodomonas strains from which the new sequences were derived were not classified at the species level, we used italicized numbers instead of the species names in protein abbreviations, i.e. G1, R1 and R2. Two transcripts originated from a cryptophyte strain that has not yet been classified at the genus level, so we included C1 in the genus-species position in the corresponding protein names.

The transcripts were fused in frame with the C-terminal enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) tag, and human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were transfected with the resultant constructs. Seventeen constructs generated transmembrane currents in response to illumination (Supplementary Fig. S2); two constructs that did not generate currents were excluded from further analysis. The spectral sensitivity was determined as described previously19. In most chlorophyte (green) algae only two channelrhodopsin genes have been found20, and a historical convention is to assign the number “1” to the more red-shifted variant from the same species, and number “2”, to the more blue-shifted one21,22. Such spectrally shifted pairs also exist among ACR homologs derived from the same source organism (Fig. 1, C1ACR_023 and C1ACR_887). However, in some cryptophyte species the number of ACR paralogs was larger than two, and the difference between the spectral maxima of their photocurrents was very small, if any (Fig. 1, the three R1ACR paralogs). Therefore, we distinguished them by including the last three digits of the transcript name in the abbreviated protein names. GenBank accession numbers, source organisms, transcript names, the wavelength of the maximal sensitivity and protein name abbreviations are listed in Table 1.

An example of a spectrally shifted ACR pair from a single cryptophyte species (C1ACR_023 and C1ACR_887), and an example of three spectrally matching ACRs from another species (R1ACR_367, R1ACR_877 and R1ACR_741). The initial slopes of photocurrents were measured in the linear range of the intensity dependence, corrected for the quantum density, and normalized to the maximal value obtained for each protein (for more detail see Methods). The data points are the mean values ± sem (n = 4–6 measurements in 3–4 cells). The spectra of other proteins were measured in a similar way and the resultant spectral maxima are listed in Table 1.

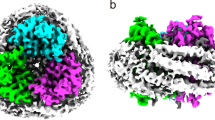

All of the new ACR homologs are natural chloride-conducting channelrhodopsins

To test whether the new ACR homologs indeed conduct anions we measured the current-voltage relationships and determined the shift of the reversal potentials (Er) upon partial replacement of Cl− in the bath with non-permeable Asp−, as was done earlier for GtACRs and PsuACR111,14. Representative series of currents traces recorded from PsuACR_973 (nicknamed ZipACR based on its robust currents, rapid kinetics, and function in neuron silencing shown below) in the standard bath (black lines) and after replacement (red lines) are shown in Fig. 2a, and the corresponding current-voltage relationships (IE curves) for the peak and stationary currents are shown in Fig. 2b. In contrast to some CCRs23, ionic selectivity of natural ACRs does not change during illumination (Fig. 2b). The difference between the Er measured for the peak and stationary currents was <2 mV for all tested natural ACRs. Therefore, Er shifts were calculated for the currents averaged over the entire 1-s illumination period to improve the accuracy of measurements. The results showed that all tested ACR homologs conduct anions (Fig. 2c).

(a) A representative series of photocurrent traces recorded in response to a 1-s light pulse of the saturating intensity from PsuACR_973 (ZipACR) expressed in HEK293 cells in the standard bath (black lines) and upon partial replacement of Cl− with Asp− in the bath (red lines). The holding voltage (Eh) was changed in 20-mV steps from −60 mV at the amplifier output (bottom trace). (b) The current-voltage relationships of peak (filled symbols) and stationary (empty symbols) photocurrents determined from current traces as shown in panel a. The data points are the mean values ± sem (n = 3 measurements in the same typical cell). The data were corrected for liquid junction potentials. (c) The Er shifts (Er in the standard bath minus Er in the Asp bath) measured for the currents averaged over the entire 1-s illumination period for all tested ACR homologs and GtACR1 mutants. The data are mean values ± sd (n = 3–5 cells). The data for the earlier studied ACRs are included for comparison.

Structural determinants of anion selectivity in natural channelrhodopsins

With a set of now 20 functionally confirmed ACRs we performed protein sequence analysis to compare natural cryptophyte ACRs with Cl−-conducting mutants engineered from chlorophyte CCRs. The first two lines in Fig. 3 show amino acid residues of CCR sequences. The third and fourth lines are the mutations introduced to confer Cl− selectivity to the latest versions of Cl−-conductive mutants of CCRs, iC++10 and iChloC9, respectively. The remaining lines show the corresponding residues in six of the confirmed natural ACRs (for the residues in the remaining 14 sequences see Supplementary Fig. S1).

The most revealing difference between the artificial and natural Cl−-conductive proteins is the position corresponding to Glu90 in CrChR2: it needed to be replaced with a neutral or positively charged residue to convert a CCR into a Cl− channel, whereas it is present in all natural ACRs. Moreover, replacement of the Glu90 homolog Glu68 in GtACR1 with a neutral (Gln) or alkaline (Lys) residue does not alter its anion selectivity, but rather strongly influences the ACR’s gating properties24, both of these effects in stark contrast to the corresponding mutations in CrChR27. Furthermore, out of two positions at which positive charges were introduced in iC++, one (Gln-117 in CrChR2) is occupied with a neutral residue, and another (Val242 in CrChR2), with a negative charge in all confirmed natural ACRs (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1). These findings indicate that the anion conduction pathways in natural and artificial ACRs are very different and the conserved Glu90 residue in helix 2 has diverged to serve different roles in the CCR and ACR mechanisms.

In addition to the aforementioned Glu90, most CCRs contain four other Glu residues in the 2nd helix and the loop between helices 2 and 3 (Glu82, Glu83, Glu90, Glu97 and Glu101 in CrChR2). It has been proposed that the absence of Glu residues in the positions corresponding to Glu83, Glu97 and Glu101 contributes to the formation of an anion-conducting pore in natural ACRs10. Indeed, in nearly all confirmed natural ACRs non-carboxylic residues are found in these three positions (Supplementary Fig. S1). However in the highly conductive ZipACR (Fig. 2), Glu101 is conserved (Supplementary Fig. S1), which demonstrates that the presence of a non-carboxylate residue at least in this position is not absolutely necessary for anion conductance.

To further test the hypothesis that the absence of Glu83, Glu97 and Glu101 determines anion conductance of natural ACRs, we introduced these glutamates in the corresponding positions in GtACR1. Glu83 and Glu97 of CrChR2 are located in the 2nd transmembrane helix, which was confirmed by the high-resolution crystal structure of a hybrid channelrhodopsin25. The corresponding residues in the predicted 2nd helix of GtACR1 are Ala61 and Ala75 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Glu101 of CrChR2 is located in the 2nd loop; therefore to determine its counterpart in GtACR1 is more difficult. Gln79 in GtACR1 is separated by 3 residues from Ala75, as is Glu101 from Glu97 in CrChR2. We generated the A61E, A75E and N79E mutants of GtACR1, expressed them in HEK293 cells and measured their IE curves in the standard buffer and upon partial replacement of Cl− with Asp− in the bath, as we did for natural ACR homologs. The shifts of the Er upon such replacement determined for each of these mutants were almost as large as those of natural ACRs (Fig. 2c). Therefore, we conclude that the presence of individual conserved residues in the 2nd helix is not sufficient to predict anion or cation selectivity of channelrhodopsins. This conclusion is corroborated by an earlier observation that Mesostigma viride channelrhodopsin 1 (MvChR1) in which Glu83 and Glu97 homologs are also replaced with neutral residues as in ACRs is in fact a CCR with one of the highest Na+/H+ permeability ratios among CCRs19. However, the A61E and A75E mutations of GtACR1 strongly decreased the current amplitude. In the standard bath (pH 7.4) at −60 mV the peak current of the A61E mutant was 48 ± 9 pA (n = 11 cells) and that of the A75E mutant, 109 ± 21 pA (n = 14 cells). On the other hand, the N79E mutation did not affect the peak current amplitude (6.0 ± 4.3 nA, n = 3 cells).

Cl−-conducting CCR mutants in which the residue corresponding to Glu83 of CrChR2 was retained generated larger photocurrents at low pH than at neutral pH7,8. The photocurrent of the A61E mutant in which a Glu residue was introduced in the corresponding position in GtACR1 did not increase at pH 5.4 (51 ± 19 pA; n = 8 cells) as compared to that at pH 7.4. This observation further confirmed the difference in anion conductance mechanisms in engineered CCR mutants and natural ACRs.

Functional Diversity in the ACR family

Photocurrents generated by new ACRs greatly differed in amplitude, kinetics and spectral sensitivity, demonstrating diversity of this protein family (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S2). The range of the wavelengths of the ACR spectral maxima extended from 445 (C1ACR_023) to 535 (C1ACR_887) nm. The degree of current inactivation during 1-s continuous illumination varied between 12.5% (R1ACR_877) and 83.6% (R2 ACR_853). PsuACR_973, R1ACR_741 and R2ACR_142 generated currents larger than those produced by the previously known ACRs. PsuACR_973 also exhibited the by far fastest current decay among all so far identified ACRs (~2.2 ms current half-decay time at zero voltage; Supplementary Fig. S4 shows the voltage dependence of the current half-decay time), the main reason we nicknamed it “ZipACR”. The dependence of ZipACR photocurrent on the light intensity is shown in Supplementary Fig. S4.

The peak current amplitude in response to a 1-s light pulse of the saturating intensity, decay rate (measured as the reciprocal of the time of the 50% decrease in the current amplitude after the light-off) and wavelength of maximal sensitivity (determined by continuous approximation of experimental data points as shown in Fig. 1) of cryptophyte ACR homologs. The amplitude and decay rate data were obtained at −60 mV holding potential in standard solutions (see Methods). The data points are the mean values; for sem values and the number of sampled cells see Supplementary Table S2. The numbers next to the data points correspond to the protein numbers in Table 1. The data for the previously known GtACR1, GtACR2 and PsuACR1 are included for comparison.

Protein sequence alignment revealed that ZipACR differs from the majority of functionally confirmed ACRs in the positions 101, 117 and 123 (according to CrChR2 numbering). The corresponding residues in ZipACR are Glu96, Asn108 and Gly114, whereas the majority of ACRs contain, respectively, Asn, Pro and Ser in these positions. We generated the E96N, N108P and G114S mutants of ZipACR and measured their photocurrents. No differences were found in the current decay rate between the mutants and the wild type (Supplementary Fig. S5), which showed that the mutated residues do not determine the fast decay kinetics of ZipACR.

ZipACR allows optical inhibition of individual neuronal spikes at unprecedentedly high frequencies

GtACR2, the fastest of the two G. theta ACRs, could be used in neurons to suppress individual spikes at firing frequencies up to 25 Hz11. However, its current decay is too slow for selective deletion of individual spikes in trains of higher frequency that may be required in certain optogenetic experiments26. Photocurrents from ZipACR exhibited ~21 times faster decay than those from GtACR2 in HEK293 cells, their amplitude was ~40% larger, and the wavelength of the maximal sensitivity was 45 nm red-shifted from that of GtACR2 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S2). We expressed ZipACR in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons under the control of an ubiquitin promoter using lentiviral delivery and tested its performance as an inhibitory optogenetic tool compared to that of GtACR2. Robust expression of ZipACR in neurons was evident from the tag fluorescence, whereas neuronal morphology and physiology in the dark was unaffected (Supplementary Fig. S6). We stimulated the neurons by somatic current injection at 50 Hz, which is the maximal frequency of regular spiking in pyramidal neurons of the rodent hippocampus16. Delivery of a 20-ms light pulse of a saturating intensity resulted in suppression of an individual spike in ZipACR-expressing neurons (Fig. 5b, top trace), whereas in GtACR2-expressing cells up to seven successive spikes were suppressed (Fig. 5b, bottom trace). The ensemble data are shown in Fig. 5c. These properties make ZipACR a likely first choice for many optogenetic applications, especially in high-frequency neurons.

(a) The decay of photocurrents generated by ACRs indicated in the figure legend in HEK293 cells after a 1-s pulse of continuous light of the saturating intensity at the wavelength of the peak absorption of the respective pigment. The traces were normalized at the stationary level measured near the end of the illumination period. (b) Photoinduced spike suppression in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons expressing ZipACR (red line) or GtACR2 (black line). Neurons were stimulated by injection of 1-ms current pulses at 50 Hz (schematically shown below). The wavelength of the 20-ms light pulses of the saturating intensity (shown on top of each trace) was 520 nm for ZipACR and 470 nm for GtACR2. (c) Photoinduced changes in the normalized spike amplitude measured as shown in panel b. The data points are the mean values ± sem (n = 7 cells). The amplitude was normalized to the mean amplitude of the last five spikes before switching on the light.

Discussion

Here we present the results of screening ACR homologs identified in high-throughput plant/protist transcriptome sequencing projects17,18. We found that all transcripts that generated photocurrents upon expression in mammalian cells acted as light-gated anion channels. This result confirmed that cation or anion selectivity of channelrhodopsins can be accurately predicted from the protein sequence information or, in other words, that ACRs and CCRs form two structurally and functionally distinct protein families. When only three natural ACRs were known, testable prediction of structural determinants of their anion conductance was difficult. The new expanded set of 20 functional sequences will serve as a better guide towards this goal.

Two sequences closely related to functional ACRs were found to generate no measurable photocurrents upon heterologous expression. This was not unusual, because one of three ACR homologs in G. theta also generated no photocurrents despite its robust expression in animal cells11, and many sequences highly homologous to CCRs were non-electrogenic when expressed in HEK cells or neurons27,28. The most likely explanation is improper folding of these algal proteins in animal cells that does not influence fluorescence of the C-terminal tag but disrupts their channel function.

Comparison of the mutations introduced in CCRs to convert them into Cl−-conducting channels with the corresponding positions in natural ACRs revealed a difference rather than a “striking convergence” as stated elsewhere10,26. The most conspicuous feature is the universal conservation of Glu90 (according to CrChR2 numbering) in all tested ACRs, which was replaced with a positive charge in the ChloC and iChloC Cl−-conducting mutants7,9 and with a neutral residue in the iC1C2 and iC++ mutants8,10. According to our analysis of the laser-evoked photocurrents and spectral transitions of purified wild-type GtACR1 and its mutants, Glu68, which corresponds to Glu90 in CrChR2, likely serves as a negative counterion and proton acceptor at least at high and neutral pH29. A Resonance Raman spectroscopy study suggested that Glu68 exists in a neutral state in unphotolyzed GtACR130, but notes that this residue may become transiently deprotonated during the photocycle as was earlier proposed for Glu169 in cation channelrhodopsin 1 from Chlamydomonas augustae (CaChR1)31.

In addition to the Glu90 homolog, all ACRs contain a Glu residue in the position of Val242 in CrChR2, in which a positive charge was introduced in the iC++ mutant10. Furthermore, we showed that although Glu residues corresponding to Glu83 and Glu101 of CrChR2, neutralized in Cl−-conducting mutants, are also neutral in most ACRs, introducing these glutamates in GtACR1 did not eliminate its anion selectivity.

Coupling between the chromophore photochemical reactions and channel opening in ACRs and CCRs appear to be very different. In CCRs the first phase of formation of an M-like intermediate with a deprotonated Schiff base occurs on the μs time scale, i.e. Schiff base proton transfer precedes channel opening32. In contrast, proton transfer accompanying M formation in the photocycle of ACRs is ~50 times slower than channel opening15,29.

In cation-conducting CrChR2 mutation of the Schiff base counterion (a homolog of Asp85 in bacteriorhodopsin) to a neutral residue resulted in profoundly accelerated kinetics of channel closing33. All so far confirmed ACRs contain a non-carboxylic residue in this position (Supplementary Fig. S1), but differ ~50 times in their current decay rate (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S2), indicating that it is regulated by other residues. Previously, we identified Glu68 (the homolog of Glu90 in CrChR2) in the middle of the 2nd helix as required for the fast phase of channel closing in GtACR129. This residue is universally conserved in ACRs, as is a homolog of Cys128 in CrChR2, mutation of which affects the slow phase of channel closing in GtACR129. Photocurrents from all five ACRs found in Rhodomonas sp. strain CCMP768 exhibit slower decay as compared to ACRs from other cryptophytes, which probably reflects the cellular physiology of this alga.

Among new ACRs ZipACR appears to be most promising for optogenetic applications, because it exhibits much faster current decay comparable to that of rhodopsin ion pumps most frequently used as optogenetic inhibitors3,34. ZipACR current amplitude is even greater than that of the potent earlier studied GtACRs, and has long-wavelength sensitivity. In cultured mouse hippocampal neurons ZipACR outperformed GtACR2 for precise inhibition of individual spikes in 50-Hz trains, the highest frequency for sustained spiking in this neuronal type16. At 25-Hz stimulation suppression of individual spikes could also be achieved using GtACR2 and stimuli of lower intensity, but only at the expense of time resolution because a longer time was needed to reach sufficient hyperpolarization of the membrane11.

The upper limit of the firing frequency at which ZipACR can suppress individual spikes can be roughly estimated from the time constant of its current decay in neurons. The rate constant obtained by single exponential fit was 2.3 ± 0.4 ms (mean ± sem, n = 9 cells; pooled data at the holding voltages from −60 to −20 mV). Therefore, 90% channel closing would take place within <6 ms, enabling single spike suppression in neurons firing up to at least 180 Hz.

Our expansion of the family of natural ACRs to include 20 functional members provides the foundation for further deciphering anion conductance mechanisms of these proteins and for their molecular engineering to better suit the needs of inhibitory optogenetics.

Methods

Search strategy for transcriptomes

Over 2000 transcriptomes from two sequencing projects, the MMETS project17 and 1KP project18 were searched using probabilistic inference methods based on profile hidden Markov models (profile HMMs) implemented in HMMER software (version 3.1b2; ref. 35). Initially a profile HMM was built from previously known ACR sequences using default parameters. When resultant sequences from preliminary transcriptome searches were confirmed by electrophysiological measurements to be functional ACRs, these sequences were used in a recursive manner for the construction of profile HMMs to search the data again. A sample profile HMM is included in the Supplementary Material and can be viewed on Skyline web server36. Calling HMMER3 tools, parsing the results, and retrieving and renaming sequences was automated with Python 2.7 and the Biopython module37. HMMER3 tools were called with default parameters as shown in the Supplementary Note. Sequences exceeding a score of 70 were aligned to the search profile by the hmmalign tool of HMMER3. The alignment obtained was checked manually to remove partial sequences as well as almost identical sequences from the same transcriptomes that varied only in terminal positions, not in the transmembrane region. The manual editing was done with AliView 1.17.138 and SeaView 1:4.5.1-139. For automatic alignments MAFFT 7.164b was used40.

Molecular biology

DNA polynucleotides encoding the 7TM domains of transcripts showing homology to G. theta ACRs optimized for human codon usage were synthesized (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ) and cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in frame with an EYFP tag for expression in HEK293 cells. The sequence information was deposited in GenBank (for accession numbers see Table 1). For expression in neurons, ZipACR-EYFP fusion construct was transferred to the pFUGW vector backbone41. Mutants were generated using Quikchange XL kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and verified by sequencing.

HEK293 recording

HEK293 (human embryonic kidney) cells were transfected using the ScreenFectA transfection reagent (Waco Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA). All-trans-retinal (Sigma) was added as a stock solution in ethanol at the final concentration of 5 μM. Measurements were performed 48–72 h after transfection with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) using the 2 kHz low-pass Bessel filter. The signals were digitized at 5 kHz with a Digidata 1440 A using pClamp 10 software (both from Molecular Devices). Patch pipettes with resistances of 2–5 MΩ were fabricated from borosilicate glass. The pipette solution contained (in mM): KCl 126, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 0.5, Na-EGTA 5, HEPES 25, pH 7.4. The standard bath solution contained (in mM): NaCl 150, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1, glucose 5, HEPES 10, pH 7.4. A 4 M KCl bridge was used in all experiments, and possible diffusion of Cl− from the bridge to the bath was minimized by frequent replacement of the bath solution with fresh buffer. Series resistance was periodically checked during recording, and cells showing >20% change were not included in the analysis. All current-voltage dependencies were corrected for liquid junction potentials calculated using the ClampEx built-in LJP calculator. Continuous light pulses were provided by a Polychrome IV light source (T.I.L.L. Photonics GMBH, Grafelfing, Germany) at the half-bandwidth 15 nm in combination with a mechanical shutter (Uniblitz Model LS6, Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY; half-opening time 0.5 ms). The light intensity was attenuated with neutral density filters. Maximal quantum density at the focal plane of the 40× objective lens was 7.6 mW/mm2 for 520 nm. For measurements of the action spectra cells were illuminated with monochromatic (half-bandwidth 10 nm) of low light intensity pulses within the linear range of the dependence. The initial slope of the photocurrent was assessed from the mean amplitude of the signal recorded during the close to linear rise of the current, usually during the first 5–15 ms depending on the rate of photocurrent saturation. To avoid possible changes during the measurements, the spectral sensitivity was scanned first from the shortest wavelength to the longest one and then again in the reversed order. The data were corrected for quantum density measured for each wavelength with a calibrated photodiode. All measurements were carried out at room temperature (25 °C).

Neuronal lentiviral transduction and recording

Lentivirus was produced in HEK293FT cells (Invitrogen) through triple-transfection of plasmids pCMV-VSVG, pΔ8.9 and pFUGW-ZipACR-EYFP. The virus was purified from the cell culture supernatant by ultracentrifugation through a 20% Sucrose layer at 20,000 rpm in an SW32 rotor for 2 hours. Neurons isolated from E18 mouse hippocampi purchased from BrainBits (Springfield, IL) by papain digestion were cultured on top of a glia feeder layer in NbActiv4 medium (BrainBits) supplemented with all-trans retinal (0.4 μM). BrainBits collects the brains using procedures that are approved by their Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Neurons were infected with lentivirus one day after plating. Patch clamp measurements were carried out 9–14 days after lentivirus infection. The same photoexcitation source and measuring setup was used as described above for HEK cells, except that neurons were bathed in Tyrode’s solution (in mM: KCl 2, NaCl 125, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 3, glucose 30, HEPES 25, pH 7.3) and the pipette solution contained (in mM): K gluconate 135, MgCl2 2, HEPES 20, pH 7.2. Spiking was measured in the current clamp mode at room temperature (25 °C). For measurement of the spike thresholds, neurons were injected with a current ramp (0–1000 pA, 1 s) in the dark.

Analysis of neuronal morphology

Hippocampal neurons at day 14 post-transduction were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed, permeabilized (0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS), washed once more, and blocked with 2% goat serum in PBS for 30 min. They were incubated with rabbit anti-GFP IgG (Life technologies, 1:200) and mouse anti-MAP2 IgG1 (Synaptic Systems, 1:500); or with polyclonal rabbit anti-synapsin antibody42 (E028, 1:1000) and guinea pig anti-Tau IgG2a (Synaptic Systems, 1:500) at 4 °C overnight. They were washed and secondarily stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG at room temperature for 1 hour, washed and mounted with ProLongDiamondAntifade with DAPI mounting medium (Molecular Probes). Images were obtained with the Zen software using an LSM 510 META laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The laser wavelengths were 488 nm (KrAr), 543 nm (HeNe), and 633 nm (HeNe). Emission filters BP 490-510, BP 560-615 and LP 650 were used, respectively. Primary dendrites from randomly selected neurons were identified as MAP2-positive branches originating from the soma and crossing the circumference of a 25 μm radius. Synapses (identified by synapsin staining) were quantified using PunctaAnalyzer plugin for ImageJ in a circular area with a radius of 25 μm from the soma as described43.

Statistics

Statistical data are shown as mean ± sem, unless otherwise indicated. The n values indicate the number of independent experiments (different cells, unless otherwise stated). For analysis of significance a Mann-Whitney test was used, and p values > 0.05 were considered not significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Govorunova, E. G. et al. The Expanding Family of Natural Anion Channelrhodopsins Reveals Large Variations in Kinetics, Conductance, and Spectral Sensitivity. Sci. Rep. 7, 43358; doi: 10.1038/srep43358 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Deisseroth, K. Optogenetics: 10 years of microbial opsins in neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1213–1225 (2015).

Zhang, F. et al. Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature 446, 633–639 (2007).

Chow, B. Y. et al. High-performance genetically targetable optical neural silencing by light-driven proton pumps. Nature 463, 98–102 (2010).

Maurice, N. et al. Striatal cholinergic interneurons control motor behavior and basal ganglia function in experimental parkinsonism. Cell Rep. 13, 657–666 (2015).

Parker, K. L., Kim, Y., Alberico, S. L., Emmons, E. B. & Narayanan, N. S. Optogenetic approaches to evaluate striatal function in animal models of Parkinson disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 18, 99–107 (2016).

Arguello, A. A. et al. Role of a lateral orbital frontal cortex-basolateral amygdala circuit in cue-induced cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology, doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.1157 (2016).

Wietek, J. et al. Conversion of channelrhodopsin into a light-gated chloride channel. Science 344, 409–412 (2014).

Berndt, A., Lee, S. Y., Ramakrishnan, C. & Deisseroth, K. Structure-guided transformation of channelrhodopsin into a light-activated chloride channel. Science 344, 420–424 (2014).

Wietek, J. et al. An improved chloride-conducting channelrhodopsin for light-induced inhibition of neuronal activity in vivo . Sci. Rep. 5, 14807 (2015).

Berndt, A. et al. Structural foundations of optogenetics: Determinants of channelrhodopsin ion selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 822–829 (2016).

Govorunova, E. G., Sineshchekov, O. A., Liu, X., Janz, R. & Spudich, J. L. Natural light-gated anion channels: A family of microbial rhodopsins for advanced optogenetics. Science 349, 647–650 (2015).

Mohammad, F. et al. Optogenetic inhibition of behavior with anion channelrhodopsins. Nat. Methods doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4148 (2017).

Govorunova, E. G., Cunha, C. R., Sineshchekov, O. A. & Spudich, J. L. Anion channelrhodopsins for inhibitory cardiac optogenetics. Sci. Rep. 6, 33530 (2016).

Govorunova, E. G., Sineshchekov, O. A. & Spudich, J. L. Proteomonas sulcata ACR1: A fast anion channelrhodopsin. Photochem. Photobiol. 92, 257–263 (2016).

Wietek, J., Broser, M., Krause, B. S. & Hegemann, P. Identification of a natural green light absorbing chloride conducting channelrhodopsin from Proteomonas sulcata . J. Biol. Chem. 291, 4121–4127 (2016).

Graves, A. R. et al. Hippocampal pyramidal neurons comprise two distinct cell types that are countermodulated by metabotropic receptors. Neuron 76, 776–789 (2012).

Keeling, P. J. et al. The Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP): illuminating the functional diversity of eukaryotic life in the oceans through transcriptome sequencing. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001889 (2014).

Matasci, N. et al. Data access for the 1,000 Plants (1KP) project. Gigascience 3, 17 (2014).

Govorunova, E. G., Spudich, E. N., Lane, C. E., Sineshchekov, O. A. & Spudich, J. L. New channelrhodopsin with a red-shifted spectrum and rapid kinetics from Mesostigma viride . mBio 2, e00115–00111 (2011).

Sineshchekov, O. A., Jung, K.-H. & Spudich, J. L. Two rhodopsins mediate phototaxis to low- and high-intensity light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8689–8694 (2002).

Nagel, G. et al. Channelrhodopsin-1: a light-gated proton channel in green algae. Science 296, 2395–2398 (2002).

Nagel, G. et al. Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13940–13945 (2003).

Berndt, A., Prigge, M., Gradmann, D. & Hegemann, P. Two open states with progressive proton selectivities in the branched channelrhodopsin-2 photocycle. Biophys. J. 98, 753–761 (2010).

Sineshchekov, O. A., Govorunova, E. G., Li, H. & Spudich, J. L. Gating mechanisms of a natural anion channelrhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14236–14241 (2015).

Kato, H. E. et al. Crystal structure of the channelrhodopsin light-gated cation channel. Nature 482, 369–374 (2012).

Berndt, A. & Deisseroth, K. Expanding the optogenetics toolkit. Science 349, 590–591 (2015).

Hou, S. Y. et al. Diversity of Chlamydomonas channelrhodopsins. Photochem. Photobiol. 88, 119–128 (2012).

Klapoetke, N. C. et al. Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat. Methods 11, 338–346 (2014).

Sineshchekov, O. A., Li, H., Govorunova, E. G. & Spudich, J. L. Photochemical reaction cycle transitions during anion channelrhodopsin gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E1993–2000 (2016).

Yi, A., Mamaeva, N. V., Li, H., Spudich, J. L. & Rothschild, K. J. Resonance Raman study of an anion channelrhodopsin: Effects of mutations near the retinylidene Schiff base. Biochemistry 55, 2371–2380 (2016).

Ogren, J. I. et al. Proton transfers in a channelrhodopsin-1 studied by FTIR-difference spectroscopy and site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 12719–12730 (2015).

Verhoefen, M. K. et al. The photocycle of channelrhodopsin-2: Ultrafast reaction dynamics and subsequent reaction steps. Chemphyschem 11, 3113–3122 (2010).

Gunaydin, L. A. et al. Ultrafast optogenetic control. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 387–392 (2010).

Gradinaru, V., Thompson, K. R. & Deisseroth, K. eNpHR: a Natronomonas halorhodopsin enhanced for optogenetic applications. Brain Cell Biol. 36, 129–139 (2008).

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195 (2011).

Wheeler, T. J., Clements, J. & Finn, R. D. Skylign: a tool for creating informative, interactive logos representing sequence alignments and profile hidden Markov models. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 7 (2014).

Cock, P. J. et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 25, 1422–1423 (2009).

Larsson, A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 30, 3276–3278 (2014).

Gouy, M., Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 221–224 (2010).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Lois, C., Hong, E. J., Pease, S., Brown, E. J. & Baltimore, D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science 295, 868–872 (2002).

Hosaka, M., Hammer, R. E. & Südhof, T. C. A phospho-switch controls the dynamic association of synapsins with synaptic vesicles. Neuron 24, 377–387 (1999).

Ippolito, D. M. & Eroglu, C. Quantifying synapses: an immunocytochemistry-based assay to quantify synapse number. J. Vis. Exp. (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Thomas Südhof (UT Southwestern; currently at Stanford University) for a gift of anti-synapsin antibody. This work was supported by NIH grants U01MH109146 and R01GM027750, and Endowed Chair AU-0009 from the Robert A. Welch Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.S., E.G.G., and O.A.S. conceived and designed the study. O.M., M.M., and G.K.-S.W. carried out transcriptome sequencing, assembly and analysis. E.M.R. and R.J. prepared neuronal cultures and performed neuronal imaging. E.G.G. generated expression constructs and E.G.G. and O.A.S. carried out electrophysiological measurements, All authors contributed to the discussion and preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston listing J.L.S., E.G.G. and O.A.S. as inventors has filed patent applications regarding ACRs.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Govorunova, E., Sineshchekov, O., Rodarte, E. et al. The Expanding Family of Natural Anion Channelrhodopsins Reveals Large Variations in Kinetics, Conductance, and Spectral Sensitivity. Sci Rep 7, 43358 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43358

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43358

This article is cited by

-

A blue-shifted anion channelrhodopsin from the Colpodellida alga Vitrella brassicaformis

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Cre-dependent ACR2-expressing reporter mouse strain for efficient long-lasting inhibition of neuronal activity

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Aion is a bistable anion-conducting channelrhodopsin that provides temporally extended and reversible neuronal silencing

Communications Biology (2022)

-

Gating and ion selectivity of Channelrhodopsins are critical for photo-activated orientation of Chlamydomonas as shown by in vivo point mutation

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Optogenetics for light control of biological systems

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.