Abstract

Physical activity is disrupted in many psychiatric disorders. Advances in everyday technologies – such as accelerometers in smart phones – opens exciting possibilities for non-intrusive acquisition of activity data. Successful exploitation of this opportunity requires the validation of analytical methods that can capture the full movement spectrum. The study aim was to demonstrate an analytical approach to characterise accelerometer-derived activity patterns. Here, we use statistical methods to characterize accelerometer-derived activity patterns from a heterogeneous sample of 99 community-based adults with mental illnesses. Diagnoses were screened using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, and participants wore accelerometers for one week. We studied the relative ability of simple (exponential), complex (heavy-tailed), and composite models to explain patterns of activity and inactivity. Activity during wakefulness was a composite of brief random (exponential) movements and complex (heavy-tailed) processes, whereas movement during sleep lacked the heavy-tailed component. In contrast, inactivity followed a heavy-tailed process, lacking the random component. Activity patterns differed in nature between those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and a primary psychotic disorder. These results show the potential of complex models to quantify the rich nature of human movement captured by accelerometry during wake and sleep, and the interaction with diagnosis and health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mobile smart phones are ubiquitous in modern society, and their numerous sensors, such as GPS (Global Positioning System), gyroscopes and accelerometers, offer a unique opportunity to gather rich empirical data on free-living activity patterns1,2,3,4,5. Smart phones have been used to facilitate monitoring of early warning signs of relapse in patients with bipolar disorder (e.g. self-reporting sleep patterns)6, and smart phone accelerometers can be used to discern mood changes by monitoring the frequency and duration of bursts of activity7. Mobile technologies are crucial in the development of ‘telehealth’ systems, enabling remote interaction between patients and clinicians, and automated monitoring of symptoms8,9,10,11. Accelerometry also has potential in monitoring physical health, by measuring total activity and the distribution of sedentary bouts, which have been shown to be major risk factors for adverse physical health outcomes12. The opportunity to obtain rich behavioral data, using non-invasive methods, has elevated smart phone employment to a priority position in several large-scale international research efforts13,14,15,16,17. There is a pressing need to explore more sophisticated analytical techniques for quantifying mental illness symptoms using accelerometry18.

Previous use of accelerometry in psychiatric research has established proof-of-principle utility, but has predominantly only analyzed basic properties of the available data. For example, accelerometry has been used to distinguish subtypes of schizophrenia using simple summary statistics, namely the mean of activity counts7,19,20,21,22. Patients with schizophrenia appear to exhibit more structured activity than healthy controls or people with depression, as quantified by inter-daily stability and intra-daily variance23, but increased disorder at shorter timescales24. Increased dynamical entropy at short timescales has also been found in people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder25. Over longer times, bipolar disorder is associated with higher intra-daily variability and lower inter-daily stability26. Bipolar patients hospitalized during either manic or depressive episodes have different activity patterns quantified using measures of variability27, and circadian rhythms are related to mood variation in outpatients with euthymic bipolar disorder28. A systematic review reported that patients with depression have a lower daytime activity and higher night-time activity than individuals without depression, and concluded that analytical methods need to be improved to extract all relevant features from actigraph data18. Whilst informative, use of summary statistics fails to capture the rich complexity of human behavioral data stretching across many orders of magnitude, from a brief motion (e.g. a foot tap), to lengthy outcome-oriented endeavors (e.g. purposeful walking). Capturing the breadth of active and inactive behaviors requires techniques that quantify the entire spectrum of movement29.

Human activity can be conceptualized as a combination of internally-driven and external cue-triggered actions. Internally-driven actions are voluntary, purposeful actions, whereas externally-triggered actions are executed in response to dynamic environmental stimuli30. Although these components – volitional versus reactive – appear to arise from distinct neural processes occurring in different regions of the brain31, most free-living activities are motivated by a combination of internal and external influences. Given the broad spectrum of influences that could potentially determine the timing of any action, one might assume that free-living activity can be characterized by random, uncorrelated statistical processes (i.e., Poisson statistics). Recent work in quantifying the waiting times of inter-human communications, however, points toward non-Poisson processes governing email communication32, web browsing33 and printing requests34. Such activities are characterized by bursts of rapidly occurring events interspersed with longer waiting times, resulting in a so-called heavy-tailed distribution of the waiting time between tasks35. This suggests that other types of human activity, such as physical movement, might be of a non-Poisson nature.

Recent work building on this approach has revealed novel differences in movement patterns of adults with mental illness. In a small but intriguing study, Nakamura et al. demonstrated that the distributions of active or inactive periods in healthy adults followed distinct classes of non-Poisson models36. They showed that active distributions followed a stretched exponential (Weibull) form, implying that we become “trapped” in active states: that is, the longer we are active, the less likely we are to cease movement at any particular moment. In contrast, inactive distributions followed a power-law form, implying that inactive periods do not have a characteristic time scale. Moreover, the inactive distributions in patients with depression followed the same power-law form as healthy adults, but with an altered scaling parameter, indicating more frequent episodes of longer resting periods29,36. Further, people with schizophrenia exhibited an enhanced persistency for both inactivity and activity when compared with controls37. This method has also been used to identify motor retardation in depressed patients, with a higher scaling parameter describing patients with motor retardation38.

Accelerometry thus has substantial potential to detect clinically relevant changes in movement patterns. However, accelerometer-based studies to date have been limited by two important factors: Small sample size and the absence of robust statistical methods to compare movement patterns between mental illnesses. Moreover, analyses have employed only simple models and hence neglected the possibility that everyday activity reflects a composite of different modes of activity. Thus, the systematic validation of non-Poisson statistics in patterns of activity measured using accelerometry has not been achieved, and requires application to a large cohort with a spectrum of mental illnesses. This is a crucial prelude to broader translation of movement data acquired using mobile phones and other smart devices. Here, we demonstrate the utility of a rigorous quantitative analysis incorporating novel stochastic models for characterizing activity patterns in adults with mental illness.

Methods and Materials

Participants

One hundred and fourteen participants were recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinics and community-based mental health organizations in Brisbane, Australia. Participants were ambulatory, English speaking, and over 18 years of age, who self-identified as having a mental illness. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from The University of Queensland Behavioral and Social Sciences Human Ethical Review Committee (2012000908), and the Royal Brisbane & Women’s Hospital Human Ethical Review Committee (HREC/12/QRBW/286). These methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Of the 114 consenting participants, 13 did not complete the study. Reasons for withdrawal included lack of time (n = 2), anxiety/paranoia about the accelerometer (n = 3), forgetfulness (n = 2), self-perceived inability to adhere to the study (n = 2), and hospitalization (n = 2); two participants were withdrawn by clinical staff, because they considered their client’s mental health not suitable for participation. Data from two participants who completed the protocol were unable to be used because of an accelerometer fault (n = 1), or failure to follow the protocol (n = 1); data from 99 participants were therefore included in the analyses. The mean age was 40 (SD =11; range 18–74), and 48% were female. Formal assessment revealed considerable diagnostic heterogeneity: 83 participants screened positive for at least one of the 13 major diagnoses on the MINI-Plus, and 42 met criteria for two or more diagnoses. Positively screened diagnoses included anxiety (n = 33), psychoses (n = 31), bipolar disorder (n = 23), substance dependence (n = 23), and depression (n = 20). The cohort thus represents a typically heterogeneous population of community-dwelling adults with mental illness. Diagnostic information is provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

Data acquisition

Height and weight of all participants were measured during the first visit, and a Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI-Plus) was conducted to screen for 13 diagnoses. The MINI-Plus interview covers major depressive disorder (MDD), panic disorder (PD), agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance dependence (drug/alcohol), psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, psychotic disorder NOS), bipolar disorder 1 and 2 (BP1 and BP2), anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The MINI-Plus interview has been shown to have a sensitivity of 0.45–0.96, and specificity of 0.45–0.98 for these disorders, compared with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IIIR39.

Participants were asked to wear an ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL) on the right hip 24 hours/day for seven consecutive days. Acceleration data were sampled from the three axes at 30 Hz. Participants were asked to remove the device only to go in water (e.g. shower, swim), and to record the time to bed, time out of bed, and accelerometer non-wear times, in a diary.

Data Pre-processing

Raw acceleration data were filtered at a bandwidth of 0.25 to 2.5 Hz corresponding to the timescales of human movement40. Data were converted to counts per second (cps), and the vector magnitude was used to estimate the relative intensity of activity for each 1-second epoch. Data were also converted to counts per minute (cpm) for comparison with previous research, and daily averages of the proportion of time spent in sedentary behaviour (SB) and moderate-to-vigorous activity (MVPA) were calculated using validated thresholds: ≤100 counts per minute (cpm) and >2019 cpm, respectively41. Accelerometer non-wear time was identified from participant diaries, and from consecutive zero counts for 180 minutes or longer, and removed. Participants’ self-reported bed times were used to define their waking and sleeping data. Analyses were performed on pooled waking and sleeping data, and compared with analyses for waking and sleeping data alone. Analyses were conducted in Matlab 2016a (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States).

Participants wore the monitor for a median of 23.4 hours/day (IQR = 16.6 to 23.9). The median proportion of self-reported time spent awake, to time spent asleep, was 1.6 (IQR = 1.3 to 1.9). When considering the proportion of time that the monitor was worn in either waking hours or sleeping hours, the median ratio of these two proportions was 1.00 (IQR = 0.98 to 1.19), indicating an approximate balance between waking and sleeping data. Participants with insufficient sleep data were only included in the analysis of waking data (defined as a ratio of awake to sleep data greater than 3; ten (10%) cases had insufficient sleep data).

Data analysis

We reduced free-living activity data to a sequence of active events, and inactive waiting-times ( and

and  , respectively). These series represent accelerometer data above, and below, a threshold defined by the mean of non-zero activity counts (Figs 1 and 2)29. The respective time series are defined by

, respectively). These series represent accelerometer data above, and below, a threshold defined by the mean of non-zero activity counts (Figs 1 and 2)29. The respective time series are defined by  , and

, and  , where

, where  is the beginning (upward threshold crossing), and

is the beginning (upward threshold crossing), and  is the end (downward threshold crossing) of the ith event.

is the end (downward threshold crossing) of the ith event.

Series of (A) active events (successive durations above the threshold), and (B) inactive waiting-times (successive durations below the threshold). Data above the threshold are active events of duration  , and data below the threshold are inactive waiting-times of duration

, and data below the threshold are inactive waiting-times of duration  , where

, where  is the beginning (upward threshold crossing), and

is the beginning (upward threshold crossing), and  is the end (downward threshold crossing), of the ith event.

is the end (downward threshold crossing), of the ith event.

Cumulative probability distributions (CDFs) were derived from these active and inactive time series. CDFs characterize the entire activity spectrum of a system, and their functional form reflects the nature of the underlying generative process35. We first fitted the CDFs with a power-law model using a robust fitting procedure, in which the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic is minimized, and the log-likelihood is maximized, over all possible xmin values, and a range of likely model parameters (α = 1.1 to 5.0, in steps of 0.01)42. Previous communications have cautioned against using limited sets of competing models for observed data43 – to compare the relative successes within a more comprehensive set, the optimal xmin value for the power-law fit was used to fit four other standard competing models: (i) truncated power-law; (ii) simple exponential; (iii) stretched exponential; and (iv) log-normal. In addition to these simple and long-tailed models, we also fitted two composite models: (v) bi-exponential, and (vi) sum of exponential and truncated power-law models, representing a composite of underlying processes. All models were fitted to the data using the maximum likelihood estimation technique, which maximizes the agreement of the model with the observed data44. Table 2 gives an overview of these models, and a description of the processes they represent.

More complex models have more parameters, and thus may ‘over fit’ the data. The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) is a measure of goodness-of-fit which penalizes each model’s relative complexity, thus favoring more parsimonious models. We used the BIC to determine the best fitting model for each subject, because it applies a stronger penalty to model complexity than other model selection statistics, such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). We then used a Bayesian model selection routine to determine the most likely model to describe the entire cohort. Each competing model’s exceedance probability (φ) was calculated, representing the probability that the model generated data from a randomly chosen subject within the group45. This method of model selection has been shown to be more robust than fixed-effects analysis, or conventional frequentist tests of model evidences, particularly in the presence of outliers45. The group-averaged parameters of the successful models were then calculated as the average of each subject’s model parameters, weighted by the renormalized model evidences of the plausible models46.

Individual participant characteristics may influence which model is most successful for each participant, and the model parameters of the successful group-wise model. We investigated the influence of (i) health and demographic characteristics: age, sex, BMI, psychological distress, smoking status (ex-smoker >6 months, occasional, daily); and (ii) summary statistics of each participant’s accelerometer data: MVPA and SB. To investigate the influence of these characteristics on model selection, we performed a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test between participants with different successful explanatory models for active and inactive periods (determined by their BICs). To investigate predictors of the model parameters, hierarchical multiple regressions were performed using participant characteristics to predict the model parameters of the successful group-wise models for active and inactive periods.

Results

Acceleration data show a striking diurnal cycle of increased day-time activity and decreased (but not absent) night activity (Fig. 1). The corresponding active and inactive time series show characteristic burst-like activity (Fig. 2), with the sporadic appearance of high amplitude (lengthy) events, suggesting that standard exponential models are unlikely to compete well against candidate heavy-tailed models for these data.

Pooled waking and sleeping data

The BICs for active period CDFs indicate that a composite of exponential and truncated power-law models (Fig. 3A) was the most successful model at the individual level (n = 54), followed by power-law (n = 29), truncated power-law (n = 9) and bi-exponential (n = 7). Those described by power-law had lower MVPA than those described by the composite model (mean = 2% vs. 6%; p < 0.001). Visually, the inactive distributions appear to follow the same composite model as the active distributions (Fig. 3B); however, after penalizing for model complexity, the simpler truncated power-law form dominates. Most inactive CDFs were described by truncated power-law (n = 75); 24 were described by power-law. The truncated power-law model indicates a curtailing of inactive periods at long timescales, and transition into activity. Participant characteristics (age, BMI, sex, psychological distress, smoking status) were similar between these two groups (p > 0.052).

Cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) and model fits for (A) active durations, and (B) inactive durations. The most successful group models (denoted by thick lines) were the sum of exponential and truncated power-law for active CDFs (parameters: α = 1.73, λ = 0.03, γ = 0.42, δ = 0.48), and truncated power-law for inactive CDFs (parameters: α = 1.64, λ = 0.0002).

Exceedance probabilities quantitatively confirmed that the composite model for the active periods, and the truncated power-law for the inactive periods, were the most successful group-wise models (Table 3). Successful group-wise models identified from exceedance probabilities represent the most likely model to describe each individual’s CDF within the cohort, given the set of competing models. That is, a composite group-wise model reflects a winning composite model at the individual level, not a composite of different individual-level simple models. Multiple hierarchical regressions indicated that MVPA was a significant predictor for α, λ and μ of the composite model describing active periods; SB was also a significant predictor of α. For the truncated power-law model describing inactive periods, SB was a significant predictor for α and λ, with MVPA and smoking status also predicting α, and age also predicting λ. These results are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

CDFs generated from 60-sec epoch data (Supplementary Figure S1) were described by the simpler truncated power-law model (φ = 1.0), and lacked the two distinct regimes evident in 1-sec data (compare Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Waking vs. sleeping data

Similar characteristic behavior was found for participants’ waking patterns (Fig. 4): A sum of exponential and truncated power-laws described active distributions (φ = 0.961; Fig. 4A), and the truncated power-law described inactive distributions (φ = 0.988; Fig. 4B). Sleep exhibited an absence of heavy-tailed behavior for active distributions, following the simple exponential form (φ = 1.0; Fig. 4A). Inactive distributions during sleep were more complex, being described by the sum of exponential and truncated power-laws (φ = 1.0; Fig. 4B). Model statistics are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

During waking hours, the mean proportion of daily time spent in MVPA and SB was 4.5% (SD = 4.5%) and 65% (SD =11%), respectively. Other summary statistics of waking behaviour have been presented elsewhere47.

Subgroup comparisons

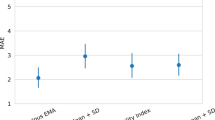

Prior research and clinical observations suggest that different clinical disorders may be characterized by distinct differences in activity patterns48. We compared activity patterns between participants with psychotic and bipolar disorders. Participants in these groups had similar age (mean = 45.1 vs. 45.9; p = 0.75), BMI (mean = 31.8 vs. 31.1; p = 0.72), distress (mean = 11.5 vs. 13.4; p = 0.23), SB (mean = 65% vs. 62%; p = 0.47), and sex (female = 31% vs. 50%; p = 0.26), but participants with psychotic disorders had higher MVPA than those with bipolar disorder (mean = 2.8% vs. 8.4%; p = 0.003). A composite of exponential and power-law models described psychoses, whereas a simpler power-law model described bipolar disorder (Fig. 5). We further confirmed that these two groups were generated from different distributions using the log Bayes factor (LogBF = 13.2, F-statistic = 7.5, corresponding to strong evidence).

Upper panels (A,B) represent exceedance probabilities for active distributions; lower panels (C,D) represent exceedance probabilities for inactive distributions. Left panels (A,C) show results of participants with bipolar disorders (n = 14), right panels (B,D) show results of participants with psychotic disorders (n = 13). Active distributions were best described by a power-law distribution for participants with bipolar disorders (exceedance probability φ = 0.77; parameter: α = 3.19), and a sum of exponential and truncated power-law for participants with psychotic disorders (exceedance probability φ = 0.79; parameters: α = 1.85, λ = 0.01, γ = 0.55, δ = 0.47). Inactive distributions were similar for both groups, being described by truncated power-laws, with parameters: α = 1.62, λ = 0.0002, and α = 1.69, λ = 0.0002, for participants with bipolar and psychotic disorder, respectively.

Physical activity and metabolic health have been increasingly recognized as crucial in people with psychoses49. We thus compared the group-averaged model parameters between obese (BMI > 32; n = 16) and non-obese (BMS < 32; n = 12) participants with psychotic disorders, using a Mann Whitney-U test. These participants had similar age (mean = 44 vs. 38; p = 0.07), distress (mean = 13 vs. 16; p = 0.63), SB (mean = 65% vs. 65%; p = 0.91), MVPA (mean = 3% vs. 5%; p = 0.21) and sex (female = 55% vs. 40%; p = 0.22). The truncation parameter was significantly higher for obese (λ = 0.02) than non-obese participants (λ = 0.003; p = 0.03).

Threshold variation

To verify that our results are insensitive to the exact choice of the threshold, we varied the threshold over a large range, from 0.5 to 1.5 times the mean of non-zero counts (Fig. 6). The inactive period CDFs, and corresponding parameter estimates, are robust over a wide range of threshold values. On average, the scaling parameter α changed by less than 10% over the range of threshold values. More variation was observed for the active period CDF and model parameters: on average, the scaling parameter α changed by less than 50% over the range of threshold values.

The chosen threshold was defined as the mean of non-zero activity counts, and varied by +/−50%. Data stability is shown for (A) active CDFs, and (B) inactive CDFs. Stability of the successful model parameters shown for (C,D,E,F) active distributions (parameters α, λ, γ, and δ of sum of exponential and truncated power-law), and (C,D) inactive distributions (parameters α and λ of truncated power-law); y-axes represent the parameter’s proportional change from the chosen threshold.

Discussion

Monitoring free-living physical activity patterns has important applications in psychiatry, for which mobile phones offer a powerful “real world” medium for data acquisition. However, validation of robust analytical techniques for the characterization of movement patterns is needed prior to broader implementation. Using a novel analytical method to analyze accelerometer data from adults with mental illness, we demonstrated that the stochastic models that best describe behavior are more complex than previously thought. This approach can be applied to accelerometer data acquired from mobile phones, and may have broader applications in monitoring severity and progression of other psychiatric and neurological disorders, such as dementia, Alzheimer’s50 and Parkinson’s disease51.

Our main finding was that free-living activity in our heterogeneous clinical sample was described by a previously unrecognized composite of two distinct regimes of behavior. Short duration (~10 s) exponential behavior may be caused by externally-triggered reactions to environmental stimuli, whereas longer duration (~1000 s) heavy-tailed activity may be caused by internally-driven cognitive processes responsible for task priority queuing32. Our data suggests that both movement and the cessation of movement have characteristic time scales: Inactive distributions spanned four orders of magnitude (1 second to ~2.5 hours), and active distributions spanned three orders of magnitude (1 second to ~17 minutes). Here, truncation of active distributions may be caused by the energetic extent of the system (e.g. fatigue), or the completion of tasks, resulting in cessation of meaningful activity. During periods of rest, the need to respond to internal and external influences (e.g. hunger, adjustments while seated, the development of a task priority) prevail at long timescales, and transition into activity. These findings help constrain the type of generative dynamics occurring in the cortical areas associated with motor preparation of self-initiated movement, such as the anterior mid-cingulate cortex and the supplementary motor area52. Whereas uncorrelated, random events yield exponential CDFs, the presence of long-tailed statistics in time series data speaks to more complex underlying processes, such as temporal memory, metabolic constraints and strong feedback35. These findings thus help constrain the type of underlying dynamics occurring in the cortical areas associated with motor preparation of self-initiated movement such as the anterior mid-cingulate cortex and the supplementary motor area52. In particular, while the neural substrates for these areas are well known, the dynamics that arise from their interactions – and that support movement onset and maintenance – are not well known. The presence of long-tailed statistics and composite statistical models suggests that the underlying dynamics occur in the presence of nonlinear instabilities and, possibly, multi-attractor systems35,53,54. This is an intriguing area that warrants further study.

Previous research has found that power-law and stretched exponential (Weibull) models best describe the cumulative distributions of inactive and active periods, respectively36. Differences between previous research and our findings may arise from the limited number of previous models studied, the absence of a formal inversion scheme, and the different time scales used (data averaged over 30-second55, or 60-second epochs29,36,37,38) which appears to be insensitive to this composite behavior. The position of accelerometer wear also influences the resultant activity pattern56: we used hip-worn monitors which measure “whole body” movement (and may more closely mimic the position of a mobile phone), whereas previous studies have used wrist-worn devices.

We also found that heavy-tailed behavior was not evident during sleep. The observed dominance of exponential behavior during sleep may support the preceding hypothesis, because higher order task queuing is removed during sleep, superseded by environmental responses (e.g. uncomfortable sleep position), or lower order cognitive processes (e.g. dreams). The distinction between ‘sleep’ and ‘awake’ data, however, was made from self-reported time to bed and time out of bed, which does not consider waking periods in bed (e.g. sleep latency, awakenings), or napping during the day. The Bayesian model selection routine is robust to outliers, so participants with particularly restless sleeps, or extensive daytime napping, are not likely to have altered the group-wise model selection.

The utility of these findings is exemplified by our application of a comprehensive set of competing models to the data, and the quantification of group-based likelihood of the models using a Bayesian approach. Previous studies have applied a smaller number of model hypotheses to activity data, which can lead to misinformed conclusions57, and have not formally appraised group-wise model success. We used a threshold defined by the mean of activity counts to define the time-series of activity or inactivity, consistent with previous literature29,36,37. This approach may be advantageous because the threshold is driven by the data, and may therefore be more sensitive to differences in activity patterns. However, other widely accepted accelerometer statistics use externally-validated thresholds that correspond with categories of energy expenditure. Whilst useful for determining the time spent at different intensities of activity, these thresholds are dependent upon the method of validation (e.g. lab-based vs. free-living) and individual characteristics (e.g. age, sex, BMI)58, which can produce large discrepancies in outcomes59. Identification of potentially abnormal activity patterns using our presented analyses would require comparison with a control group matched on the time spent in physical activity. Future research could investigate threshold-free analyses.

We additionally performed a proof-of-principle contrast between participants with different psychiatric diagnoses. Interestingly, the short-duration exponential behavior evident in the active distributions of participants with a psychotic disorder was absent in those with bipolar disorder. Instead, a simple power-law model best governed the active distributions in bipolar patients, potentially representing a reduction in reactional behavior (Fig. 5). This finding is broadly consistent with the hypothesis of neuronal dysregulation of dopamine in bipolar disorder, causing over-excitation of the processes responsible for volition60. Previous research has found that bipolar patients in a manic episode exhibited a greater degree of exploratory behavior when faced with a novel environment7,61, which may be reflected in the present findings, and may have clinical implications for the monitoring of psychopathological symptoms. Interestingly, participants with psychotic disorders had a higher level of moderate-to-vigorous activity than bipolar patients. This may seem contradictory with the preceding hypothesis, however, the composite model describing activity patterns of participants with psychoses curtails active periods at long durations indicating a ‘ceiling’ effect, whereas the power-law describing those with bipolar disorder does not have a characteristic time-scale. Future research should compare participants with different psychiatric diagnoses matched by physical activity level to verify if the difference in activity patterns between diagnostic groups are independent of activity level.

Adults with mental illness have poor physical health compared with the general population62. Changes in activity patterns may reflect a higher risk of developing physical complications. We examined a limited number of parameters pertaining to physical health, and found that the model statistics for obese people with psychotic disorders were different from those who were not obese. A larger truncation parameter was found for the active distributions of those who were obese, indicating a reduced likelihood of remaining active for longer periods of time. This could be due to a higher propensity to fatigue in obese participants with a psychotic disorder, possibly driven by ‘negative’ symptomatology. The application of this analytical method is formative, however, and a larger sample would be required to investigate the possible influences of health and demographic characteristics on model parameters.

Our data were recorded during free-living conditions, sampled from a diverse sample of adults across a range of mental illnesses. While this approach has strong ecological validity, it also presents a number of limitations. In particular, there were only 14 participants that had a single psychiatric diagnosis without comorbidities, which limits investigation into the specific influence of diagnosis, medications, and demographic characteristics. Sixteen participants did not meet the MINI-Plus criteria for a current mental illness (as indicated in Table 1, note c); however, these participants may have had symptoms of poor mental health that did not reach clinical levels. The sample heterogeneity may also have advantages, in that the application of this analytical method to a broad sample is more reflective of real world conditions.

Future work could focus on applying these analytical techniques to larger samples of participants with a specific psychiatric diagnosis, and correlating model parameters with dimensional symptomatic measures (e.g. positive and negative symptoms of people with schizophrenia) rather than contrasts between diagnostic categories. A previous study reported that avolition, but not qualitative motor disturbance, was associated with reduced activity levels in adults with schizophrenia21; analyses presented here quantify the complete activity distribution, and may have utility for detecting motor disturbances38. Our analyses could also be used to quantify sleep disturbances. Indictors of disturbed motor activity or sleep could be used as early warning signs of relapse and to promote early intervention, or to assess treatment progression or efficacy. We analysed pooled waking and sleeping data, and waking and sleeping data separately; this technique could also be applied to shorter time periods (e.g. ~1-hr) similar to other research63. Further, the parameters of the active and inactive distributions for each participant may correlate with over- or under-activity of different brain regions, similar to previous research64. Future work should compare activity patterns with a healthy comparison group to detect potentially abnormal movement patterns associated with particular illnesses.

In summary, we presented a novel approach that may have applications in the monitoring of pathophysiological symptoms related to movement abnormalities in adults with mental illness. This methodology holds promise for broader application, particularly with the roll-out of mobile phone-based psychiatry research.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chapman, J. J. et al. Quantification of free-living activity patterns using accelerometry in adults with mental illness. Sci. Rep. 7, 43174; doi: 10.1038/srep43174 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Tully, L. M. et al. Using a Novel Mobile Health Application to Monitor Symptoms and Functioning in an Early Psychosis Program: Preliminary Data on Feasibility and Acceptability. Biol Psychiatry 75, 387S–387S (2014).

Smith, J. C. & Schatz, B. R. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 757 (American Medical Informatics Association).

Bardram, J. E. et al. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2627–2636 (ACM).

Burns, M. N. et al. Harnessing context sensing to develop a mobile intervention for depression. J Med Internet Res 13 (2011).

Depp, C. A. et al. Mobile interventions for severe mental illness: design and preliminary data from three approaches. J Nerv Ment Dis 198, 715 (2010).

Marcu, G., Bardram, J. E. & Gabrielli, S. In International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare. 1–8 (IEEE).

Minassian, A. et al. The quantitative assessment of motor activity in mania and schizophrenia. J Affect Disord 120, 200–206 (2010).

Patrick, K., Griswold, W. G., Raab, F. & Intille, S. S. Health and the mobile phone. Am J Prev Med 35, 177–181 (2008).

Morris, M. & Guilak, F. Mobile heart health: project highlight. IEEE Pervasive Comput 8, 57–61 (2009).

Pharow, P., Blobel, B., Ruotsalainen, P., Petersen, F. & Hovsto, A. In Medical Informatics in a United and Healthy Europe. 1012–1016 (2009).

Andreu-Perez, J., Leff, D. R., Ip, H. & Yang, G.-Z. From Wearable Sensors to Smart Implants–Toward Pervasive and Personalized Healthcare. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on 62, 2750–2762 (2015).

Hamilton, M. T., Healy, G. N., Dunstan, D. W., Zderic, T. W. & Owen, N. Too little exercise and too much sitting: inactivity physiology and the need for new recommendations on sedentary behavior. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2, 292–298 (2008).

Gravenhorst, F. et al. Mobile phones as medical devices in mental disorder treatment: an overview. Pers Ubiquitous Comput 19, 335–353 (2015).

Tara A Niendam, L. T., Kathleen Burch, Cameron S Carter. Translational cognitive and affective neuroscience: Mobi, http://carterlab.ucdavis.edu/research/mobi.php (2015).

Welbourne, E. & Tapia, E. Building the Community’s Largest Labeled Mobile and Sensor Dataset, http://crowdsignals.io/ (2016).

Niendam, T. A., Tully, L., Burch, K. & Carter, C. S. In International Congress on Schizophrenia Research. S326–S327 (2015).

Welbourne, E. & Tapia, E. M. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing: Adjunct Publication. 873–877 (ACM).

Burton, C. et al. Activity monitoring in patients with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 145, 21–28 (2013).

Walther, S. et al. Quantitative motor activity differentiates schizophrenia subtypes. Neuropsychobiology 60, 80–86 (2009).

Walther, S., Horn, H., Koschorke, P., Müller, T. J. & Strik, W. Increased motor activity in cycloid psychosis compared to schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry 10, 746–751 (2009).

Docx, L., Sabbe, B., Provinciael, P., Merckx, N. & Morrens, M. Quantitative psychomotor dysfunction in schizophrenia: a loss of drive, impaired movement execution or both? Neuropsychobiology 68, 221–227 (2013).

Apiquian, R. et al. Variations of rest–activity rhythm and sleep–wake in schizophrenic patients versus healthy subjects: An actigraphic comparative study. Biol Rhythm Res 39, 69–78 (2008).

Berle, J. O., Hauge, E. R., Oedegaard, K. J., Holsten, F. & Fasmer, O. B. Actigraphic registration of motor activity reveals a more structured behavioural pattern in schizophrenia than in major depression. BMC research notes 3, 149 (2010).

Hauge, E. R., Berle, J. Ø., Oedegaard, K. J., Holsten, F. & Fasmer, O. B. Nonlinear analysis of motor activity shows differences between schizophrenia and depression: a study using Fourier analysis and sample entropy. PloS one 6, 1–10 (2011).

Perry, W. et al. A reverse-translational study of dysfunctional exploration in psychiatric disorders: from mice to men. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66, 1072–1080 (2009).

Jones, S. H., Hare, D. J. & Evershed, K. Actigraphic assessment of circadian activity and sleep patterns in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 7, 176–186 (2005).

Krane-Gartiser, K., Henriksen, T. E. G., Morken, G., Vaaler, A. & Fasmer, O. B. Actigraphic assessment of motor activity in acutely admitted inpatients with bipolar disorder. PloS one 9, e89574 (2014).

Krane-Gartiser, K. et al. Mood and motor activity in euthymic bipolar disorder with sleep disturbance. J Affect Disord 202, 23–31 (2016).

Nakamura, T. et al. Of mice and men - universality and breakdown of behavioral organization. PLoS One 3, e2050 (2008).

Jahanshahi, M. Willed action and its impairments. Cogn Neuropsychol 15, 483–533 (1998).

Krieghoff, V., Waszak, F., Prinz, W. & Brass, M. Neural and behavioral correlates of intentional actions. Neuropsychologia 49, 767–776 (2011).

Barabasi, A.-L. The origin of bursts and heavy tails in human dynamics. Nature 435, 207–211 (2005).

Dezsö, Z. et al. Dynamics of information access on the web. Phys Rev E 73, 066132 (2006).

Harder, U. & Paczuski, M. Correlated dynamics in human printing behavior. Physica A 361, 329–336 (2006).

Roberts, J. A., Boonstra, T. W. & Breakspear, M. The heavy tail of the human brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 31, 164–172 (2015).

Nakamura, T. et al. Universal scaling law in human behavioral organization. Phys Rev Lett 99, 1381031–1381034 (2007).

Sano, W. et al. Enhanced persistency of resting and active periods of locomotor activity in schizophrenia. PloS one 7, e43539 (2012).

Krane-Gartiser, K., Vaaler, A. E., Fasmer, O. B. & Morken, G. Distribution and Characteristics of Active and Inactive Periods Distinguish Unipolar Depression With and Without Motor Retardation. J Clin Psychiatry 77, 841–842 (2016).

Sheehan, D. V. et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59, 22–33 (1998).

John, D. & Freedson, P. ActiGraph and actical physical activity monitors: a peek under the hood. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44, S86–S89 (2012).

Troiano, R. P. et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40, 181–188 (2008).

Clauset, A., Shalizi, C. R. & Newman, M. E. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM review 51, 661–703 (2009).

Jansen, V. A., Mashanova, A. & Petrovskii, S. Comment on “Lévy walks evolve through interaction between movement and environmental complexity”. Science 335, 918–918 (2012).

Wasserman, L. All of Statistics: A Concise Course in Statistical Inference. (Springer-Verlag, 2003).

Stephan, K. E., Penny, W. D., Daunizeau, J., Moran, R. J. & Friston, K. J. Bayesian model selection for group studies. Neuroimage 46, 1004–1017 (2009).

Penny, W. D. et al. Comparing families of dynamic causal models. PLoS Comput Biol 6, e1000709 (2010).

Chapman, J. J., Fraser, S. J., Brown, W. J. & Burton, N. W. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour of adults with mental illness. J Sci Med Sport (2015).

Teicher, M. H. Actigraphy and motion analysis: new tools for psychiatry. Harv Rev Psychiatry 3, 18–35 (1995).

Mitchell, A. J. et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia bulletin 39, 306–318 (2013).

Coogan, A. N. et al. The circadian system in Alzheimer’s disease: disturbances, mechanisms, and opportunities. Biol Psychiatry 74, 333–339 (2013).

Chastin, S. F. et al. The pattern of habitual sedentary behavior is different in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 25, 2114–2120 (2010).

Nguyen, V. T., Breakspear, M. & Cunnington, R. Reciprocal interactions of the SMA and cingulate cortex sustain premovement activity for voluntary actions. J Neurosci 34, 16397–16407 (2014).

Friston, K., Breakspear, M. & Deco, G. Perception and self-organized instability. Front Comput Neurosci 6, 44 (2012).

Kelso, J. S. Dynamic patterns: The self-organization of brain and behavior (MIT press, 1997).

Chialvo, D. et al. How we move is universal: scaling in the average shape of human activity. Papers in Physics 7, 070017 (2015).

Atallah, L., Lo, B., King, R. & Yang, G.-Z. Sensor positioning for activity recognition using wearable accelerometers. IEEE transactions on biomedical circuits and systems 5, 320–329 (2011).

de Jager, M., Weissing, F. J., Herman, P. M., Nolet, B. A. & van de Koppel, J. Lévy walks evolve through interaction between movement and environmental complexity. Science 332, 1551–1553 (2011).

Jeran, S., Steinbrecher, A. & Pischon, T. Prediction of activity-related energy expenditure using accelerometer-derived physical activity under free-living conditions: a systematic review. Int J Obes (2016).

Loprinzi, P. D. et al. The relationship of actigraph accelerometer cut-points for estimating physical activity with selected health outcomes: results from NHANES 2003–06. Res Q Exerc Sport 83, 422–430 (2012).

Weissenborn, R. & Winn, P. Regulatory behaviour, exploration and locomotion following NMDA or 6-OHDA lesions in the rat nucleus accumbens. Behav. Brain Res. 51, 127–137 (1992).

Perry, W. et al. Quantifying over-activity in bipolar and schizophrenia patients in a human open field paradigm. Psychiatry research 178, 84–91 (2010).

Lawrence, D., Hancock, K. J. & Kisely, S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers. BMJ 346 (2013).

Krane-Gartiser, K., Henriksen, T. E., Vaaler, A. E., Fasmer, O. B. & Morken, G. Actigraphically assessed activity in unipolar depression: a comparison of inpatients with and without motor retardation. J Clin Psychiatry 76, 1181–1187 (2015).

Walther, S. & Strik, W. Motor symptoms and schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology 66, 77–92 (2012).

Corral, A. Long-term clustering, scaling, and universality in the temporal occurrence of earthquakes. Phys Rev Lett 92, 108501 (2004).

Brown, L. et al. Statistical analysis of a telephone call center: A queueing-science perspective. J Am Stat Assoc 100, 36–50 (2005).

Buzsáki, G. & Mizuseki, K. The log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions affect network operations. Nat Rev Neurosci 15, 264–278 (2014).

Tye, M. R., Stephenson, D. B., Holland, G. J. & Katz, R. W. A Weibull Approach for Improving Climate Model Projections of Tropical Cyclone Wind-Speed Distributions. J Clim 27, 6119–6133 (2014).

Roberts, J. A., Iyer, K. K., Finnigan, S., Vanhatalo, S. & Breakspear, M. Scale-free bursting in human cortex following hypoxia at birth. J Neurosci 34, 6557–6572 (2014).

Freyer, F., Roberts, J. A., Ritter, P. & Breakspear, M. A canonical model of multistability and scale-invariance in biological systems. PLoS Comput. Biol 8, e1002634 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, The Prince Charles Hospital, Communify QLD, Footprints Inc., Mental Illness Fellowship QLD, Brooke Red, and Reclink Australia for their support and assistance with recruitment. This work was not funded from any specific grant or sponsor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. collected all data, performed analyses, and prepared the manuscript text and figures. J.R. provided advice and direct assistance with analyses. V.N. provided advice on analyses. M.B. advised on project design, and directed analyses. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chapman, J., Roberts, J., Nguyen, V. et al. Quantification of free-living activity patterns using accelerometry in adults with mental illness. Sci Rep 7, 43174 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43174

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43174

This article is cited by

-

General spectral characteristics of human activity and its inherent scale-free fluctuations

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Objective assessment of motor activity in a clinical sample of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and/or cyclothymic temperament

BMC Psychiatry (2022)

-

Patterns of activity correlate with symptom severity in major depressive disorder patients

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.