Abstract

Bmi-1, CD133, Nanog and Oct-4 have been reported as cancer stem cell (CSC) markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). However, the prognostic value of them in HNSCC remains controversial. Hence, this meta-analysis was conducted to access the association between the four CSC markers and survival outcome of HNSCC patients. A total of 22 articles with 27 studies met the inclusion criteria and the combined hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. Data analysis showed that high expression of CSC markers was associated with poor overall survival (OS) (HR = 1.93; 95% CI: 1.46–2.55, P < 0.001) and disease free survival (DFS) (HR = 4.78; 95% CI: 2.95–7.75, P < 0.001) but not disease specific survival (DSS) (HR = 1.17; 95% CI: 0.74–1.84, P = 0.50) of HNSCC patients. Subgroup analysis indicted that high expression of CD133 (HR = 2.33, 95%CI: 1.42–3.83, P < 0.001), Oct-4(HR = 2.10, 95%CI: 1.36–3.22, P = 0.007) and Nanog (HR = 2.49, 95%CI: 1.66–3.72, P < 0.001) could predict poor OS in HNSCC patients respectively whereas overexpression of Bmi-1 was not related to the reduced OS in HNSCC patients (HR = 1.32, 95%CI: 0.66–2.65, P = 0.43). Therefore, we concluded that CSC markers, especially CD133, Nanog and Oct-4, might be predictive factors in HNSCC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the most common histological type of head and neck cancer which is the sixth leading cancer by incidence worldwide, leading to more than 200,000 deaths annually1,2. Although treatments for HNSCC have been progressing rapidly recently, the overall survival of patients with HNSCC is relatively low because the regional and distant metastases are already existed at diagnosis. More seriously, the five-year survival rate of HNSCC on the whole is lower than 50%3,4.

Accumulated evidence suggests that cancer stem cells (CSCs) may played an important role in the progression and prognosis of cancers, including HNSCC5. CSCs, a small subpopulation of cancer cells, possess the ability to initiate neoplasm and sustain tumor self-renewal6. Several stem cell markers have been described for HNSCC, such as CD44, Bmi-1, CD133, ALDH1, Nanog, Oct-4 and SOX27,8,9. Furthermore, it has been reported that patients with high expression of ALDH1, CD44 and SOX2 had worse prognosis10,11,12. However, due to differences in research method, study population and sample size, the role of Bmi-1, CD133, Nanog and Oct-4 in HNSCC is still not clear to date. There are conflicting opinions about their prognostic value.

In the present study, we collected the available literatures and conducted this meta-analysis to combine the evidence of CSC markers (CD133, Nanog, Bmi-1, Oct-4) in patients with HNSCC, in order to address controversial issues.

Results

Study characteristics

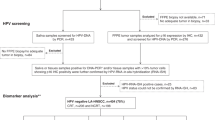

The literature selection process of the eligible studies was presented in Fig. 1. A total of 22 articles13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 including 27 studies and 2143 patients met the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis. The basic characteristics of each eligible studies were summarized in Table 1. All articles were published between 2006 and 2016, and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) scores of them were listed in Table 1 35. The majority of these studies were proceeded in Asia (n = 22), and others were conducted in Europe (n = 5). Among the 27 included studies, 9 studies involved patients with Bmi-1, 3 studies involved patients with CD133, 9 studies involved patients with Oct-4 and 6 studies involved patients with Nanog. The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 50 to 436. According to the median of all samples, 14 studies were classified as large sample size (n > 72) studies and 13 studies were small sample size (n < 72) studies. Twenty-two studies explored the prognostic value of the four markers in overall survival (OS), whereas 9 studies investigated the prognostic significance of the four markers in disease free survival (DFS) or disease specific survival (DSS).

CSC markers and OS in HNSCC

Twenty-two studies14,15,16,18,20,21,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,34 with 1759 patients reported the data of 4 CSC markers and OS in HNSCC. High expression of CSC markers was associated with poor OS (HR = 1.93; 95% CI: 1.46–2.55, P < 0.001) although with heterogeneity (I2 = 59%, Ph < 0.001; Fig. 2).

CSC markers and DSS in HNSCC

Five studies13,17,20,34 with 1182 patients showed the information of the 4 CSC markers and DSS in HNSCC. Data analysis showed that there was no significant relation between the overexpression of CSC markers and DSS (HR = 1.17; 95% CI: 0.74–1.84, P = 0.50). However, there was obvious heterogeneity (I2 = 69%, Ph = 0.01; Fig. 3A).

CSC markers and DFS in HNSCC

The association of the 4 CSC markers and DFS in HNSCC was supplied by 419,28,34 studies with 276 patients. Data analysis showed that the overexpression of CSC markers was related to poor DFS (HR = 4.78; 95% CI: 2.95–7.75, P < 0.001) without obvious heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, Ph = 0.60; Fig. 3B).

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analysis stratified by different CSC markers, ethnicity, sample size and tumor location were performed to detect the potential source of heterogeneity (Table 2). According to the stratification by different CSC markers, the finding of poor OS in patients with high expression of CSC markers was consistently found in CD133 (HR = 2.33, 95%CI: 1.42–3.83, P < 0.001; I2 = 22%, Ph = 0.28), Oct-4 (HR = 2.10, 95%CI: 1.36–3.22, P < 0.001; I2 = 40%, Ph = 0.11) and Nanog (HR = 2.49, 95%CI: 1.66–3.72, P < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Ph = 0.60) except Bmi-1(HR = 1.32, 95%CI: 0.66–2.65, P = 0.43; I2 = 81%, Ph < 0.001). Interestingly, poor DSS in patients was significantly associated with high expression of Bmi-1 (HR = 1.85, 95%CI: 1.24–2.76, P = 0.002; I2 = 0%, Ph = 0.47). There were consistent findings in Asian (HR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.37–2.80, P < 0.001; I2 = 65%, Ph < 0.001) and Caucasian (HR = 1.89, 95%CI: 1.39–2.59, P < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Ph = 0.96) between CSC markers and OS. However, overexpression of CSC markers did not predict poor DSS in Asians (HR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.61–1.34, P = 0.61, I2 = 45, Ph = 0.16). According to the subgroup analysis of tumor location, poor OS was related to CSC markers in oral/oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (HR = 2.14, 95%CI: 1.40–3.26, P = 0.004; I2 = 19%, Ph = 0.29), laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) (HR = 3.18, 95%CI: 1.75–5.78, P < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Ph = 0.58) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NEPC) (HR = 2.60, 95%CI: 1.58–4.30, P < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Ph = 0.91) without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) (HR = 1.48, 95%CI: 0.70–3.12, P = 0.30; I2 = 83%, Ph < 0.001). When it comes to the sample size, there was no significance between CSC markers and poor OS in large sample size (HR = 1.49, 95%CI: 0.97–2.30, P = 0.07, I2 = 75, Ph < 0.001) but in small sample size (HR = 2.41, 95%CI: 1.81–3.22, P < 0.001, I2 = 3, Ph = 0.41).

Sensitivity analysis and Publication Bias

Seventeen studies13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,30,34 that scored seven or more on the NOS were included in sensitivity analysis (Table 3).There was no change in the significance of most of the results except the relation between Oct-4 and OS (HR = 2.14, 95%CI: 0.97–4.74, P = 0.06, I2 = 62, Ph = 0.03), LSCC and OS (HR = 2.25, 95%CI: 0.58–8.69, P = 0.24), and NPEC and OS (HR = 2.39, 95%CI: 0.57–9.98, P = 0.23), which was shown to be no significance.

We performed a Begg’s funnel plot with using Begg’s test and Egger’s test to assess the publication bias of the included studies of OS. As showed in Fig. 4, there was no obvious publication bias in these studies (Begg’s test: P = 0.120; Egger’s test: P = 0.500).

Discussion

This meta-analysis of 27 studies including 2143 patients assessing the prognostic value of 4 CSC markers in HNSCC showed that a high expression level of CSC markers was a promising prognostic factor for lower DFS and OS in HNSCC patients. However, the expression of CSC markers had no obvious influence on DSS of HNSCC patients. According to the current results, CSC markers may play an important role in the relapse of HNSCC rather than death from HNSCC. However, considering that the sample sizes about DSS and DFS are relatively limited, our results need to be cautiously interpreted.

Bmi-1 was related to multiple human cancers which played an indispensable role in maintaining the self-renewal ability of both normal and malignant cancer stem cells. It has been reported that high expression of Bmi-1 could significantly lead to a poor OS in gastric cancer patients36. But in our subgroup analyses, Bmi-1 could not influence the OS of HNSCC patients. However, poor DSS in HNSCC patients was significantly associated with high expression of Bmi-1 with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, Ph = 0.47). It is worth noting that there was high heterogeneity between OS and HNSCC (I2 = 81%, Ph < 0.001). We tried to find what caused this. When we ruled out the study of Chen 201315, the association of poor OS and high expression of Bmi-1 was changed to be significant, meanwhile the heterogeneity was lower than before. This results suggested that we need more studies to get a conclusion whether the expression of Bmi-1 can influence the OS of HNSCC patients.

CD133, also named prominin-1, has been verified to be a CSC marker in many cancers. Previous meta-analyses showed that high expression of CD133 was responsible for the reduced OS of ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, non-small cell lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma patients37,38,39,40. Our subgroup analysis revealed that a high expression of CD133 was related to a lower OS in HNSCC patients which was in keeping with those previous analyses.

Nanog and Oct-4, also known as embryonic stem cells markers, both have the ability in maintaining the self-renewal capacity in embryonic stem cells28. Moreover, studies have showed that the co-expression of Oct-4 and Nanog could be found in hepatocellular carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma41,42. Our results suggested that the high expression of Nanog and Oct-4 could reduce the OS of HNSCC patients, respectively. In the research of Chiou et al.16, patients with high expression of both Nanog and Oct-4 were associated with lower OS than those with high expression of Nanog or Oct-4 alone16. This reminded us that more studies about the relationship of co-expression of Nanog and Oct-4 and the survival outcome of HNSCC should be conducted.

In the subgroup analysis of tumor location, poor OS was related to CSC markers in OSCC, LSCC and NEPC except ESCC. Interestingly, when we tried to find the origin of the heterogeneity in CSC markers and ESCC, we found that, as same as the result of the association of Bmi-1 and OS, the heterogeneity was lower and the result was significantly changed (HR = 2.03, 95%CI: 1.47–2.82, P < 0.001, I2 = 10, Ph = 0.34) if we discarded the study of Chen 201315. Taking this into consideration, we could not simply conclude that poor OS was not related to high expression of CSC markers in ESCC because the number of included studies was a little small and we needed more powerful evidences.

Considering the subgroup of ethnicity, the OS of the Asian and Caucasian was the same to the overall OS. The DSS of the Asian was consistent with the overall DSS while the DSS of the Caucasian was changed to be significant without heterogeneity. In the subgroup analysis of sample size, we used the median as the boundary because most of the sample size of our included studies were relatively small. As showed in Table 2, poor OS of large sample size was not significantly associated with high expression of CSC markers with high heterogeneity because Chen 201315 was in this group. Without study of Chen 201315, the results would be changed (HR = 2.09, 95%CI: 1.68–2.60, P < 0.001, I2 = 30, Ph = 0.10).

This meta-analysis has the following limitations that must be taken into consideration. First, both the number of included studies about each CSC markers and the number of included HNSCC patients in each study are relatively small, which, to some extent, may reduce the power and precision of our subcategory analyses. Second, most of the included studies were conducted in Asian and a few studies were about the Caucasians but no studies were about the black populations, which may produce potential population selection bias. Third, nonuniform cut-off value defining high and low expression of CSC markers may impact the results of this meta-analysis. Despite these limitations, we provided a comprehensive analysis of the association between CSC markers and OS/DFS/DSS of HNSCC patients. To the best of our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to systematically assess the association of Bmi-1, Oct-4, Nanog and CD133 expression with survival outcome of HNSCC. So far, there are some meta-analyses showed that high expression of CSC markers, including ALDH1, CD44 and SOX2, could predict poor OS/DFS in head and neck cancer patients10,11,12. Our results were in line with these previous analyses.

In summary, our meta-analysis revealed that high expression of CSC markers was significantly associated with poor OS and DFS but not DSS of HNSCC patients. However, because of certain limitations, different subgroup showed to some extent inconsistent results, which prompted future large-sample, well-designed with long-term follow-up to confirm and update the findings of this. Nevertheless, our study still gave some hints that CSC markers have prognostic value in HNSCC patients.

Methods

Literature search and eligibility Criteria

The databases of PubMed, Web of Science, the Cochrane library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) were thoroughly searched until July, 2016 without language restriction. The search strategy was listed as follows: (CD133 OR Bmi-1 OR Oct-4 OR Nanog) and (head and neck squamous cell carcinoma OR HNSCC OR ((oral OR laryn* OR pharyn* OR tongue OR oropharyn* OR nasopharyn* OR hypopharyn* OR trachea OR laryngopharyn* OR cervical tracheal OR cervical esophagus) AND (cancer* OR tumor* OR carcinoma* OR neoplasm*))). Two reviewers (F. Z. N and L. M. X) inspected all candidate articles independently. Discrepancies were resolved in consensus.

The inclusion criteria were: 1) the diagnosis of HNSCC was made based on pathological examination; 2) the expression of CD133 or Bmi-1 or Oct-4 or Nanog with OS/DSS/DFS about HNSCC was reported; 3) HRs and 95% CIs were provided in text or sufficient data was provided for the calculation of HRs and 95% CIs; 4) articles published as original research. In order to avoid duplicate inclusion of data, we selected only the more recent or complete article when multiple reports described the same population.

The exclusion criteria were:1) reviews, meeting abstracts, letters; 2) nonhuman studies; 3) sample size <50 patients.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (C. X. B and W. J) independently extracted the following information from included studies: author, year of publication, study country, sample size, clinicopathological parameters, cut-off value of CD133 or Bmi-1 or Oct-4 or Nanog, survival data and the tumor location. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (L. X. Y and W. H. F) independently assessed the quality of included studies by the NOS35. Studies with NOS scores of more than 7 were defined as high quality. Consensus was reached by discussion when there were inconsistent results.

Statistical Analysis

Hazard ratio (HR) was used as a summary statistic for survival outcomes as described by Parmar et al.43. An HR greater than 1 represented poor prognosis in HNSCC. Heterogeneity among primary studies was assessed by the Cochrane’s Q statistic and I2 statistic. Cochran Q test’ P value < 0.10 or I2 > 50% indicated large heterogeneity between studies and we used random effects models to calculate the pooled HR and 95% CI. Otherwise, the fixed effects model was used. We used the median as the boundary between the large and small sample size. Studies with sample size >72 were regarded as large sample size, otherwise was considered as small sample studies. Subgroup analyses stratified by different stem cell marker, ethnicity, sample size and tumor location were carried out. Sensitivity analysis were applied to high-quality studies (NOS > 6). The Begg’s funnel plots were used to evaluate publication bias. All statistical analysis were performed by using Review manager 5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and Stata 12.0 statistical software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Fan, Z. et al. Prognostic Value of Cancer Stem Cell Markers in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: a Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 43008; doi: 10.1038/srep43008 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Jemal, A. et al. Global cancer statistics. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 61, 69–90, doi: 10.3322/caac.20107 (2011).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 65, 5–29, doi: 10.3322/caac.21254 (2015).

Braakhuis, B. J., Leemans, C. R. & Visser, O. Incidence and survival trends of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in the Netherlands between 1989 and 2011. Oral oncology 50, 670–675, doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.03.008 (2014).

Fuller, C. D. et al. Conditional survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: results from the SEER dataset 1973–1998. Cancer 109, 1331–1343, doi: 10.1002/cncr.22563 (2007).

Major, A. G., Pitty, L. P. & Farah, C. S. Cancer stem cell markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Stem cells international 2013, 319489, doi: 10.1155/2013/319489 (2013).

Dalerba, P., Cho, R. W. & Clarke, M. F. Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annual review of medicine 58, 267–284, doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.062105.204854 (2007).

Qian, X. et al. Biology and immunology of cancer stem(-like) cells in head and neck cancer. Critical Reviews In Oncology Hematology 95, 337–345, doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.03.009 (2015).

Patel, S. S., Shah, K. A., Shah, M. J., Kothari, K. C. & Rawal, R. M. Cancer Stem Cells and Stemness Markers in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 15, 8549–8556, doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.20.8549 (2014).

Satpute, P. S., Hazarey, V., Ahmed, R. & Yadav, L. Cancer Stem Cells in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Review. Asian Pacific Journal Of Cancer Prevention 14, 5579–5587, doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.10.5579 (2013).

Zhou, C. & Sun, B. The prognostic role of the cancer stem cell marker aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: a meta-analysis. Oral oncology 50, 1144–1148, doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.08.018 (2014).

Chen, J. et al. Significance of CD44 expression in head and neck cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC cancer 14, 15, doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-15 (2014).

Dong, Z., Liu, G., Huang, B., Sun, J. & Wu, D. Prognostic significance of SOX2 in head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine 7, 5010–5020 (2014).

Allegra, E. et al. Nuclear BMI-1 expression in laryngeal carcinoma correlates with lymph node pathological status. World journal of surgical oncology 10, 206, doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-206 (2012).

Canis, M. et al. CD133 is a predictor of poor survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Biomarkers 12, 97–105, doi: 10.3233/cbm-130297 (2012).

Chen Y. et al. Correlation between Rhoc and Bmi-1 invasiveness and migration and prognostic of esophageal squamous carcinoma. (Chinese). Journal of Xinjiang Medical University 36, 588–591 (2013).

Chiou, S. H. et al. Positive correlations of Oct-4 and Nanog in oral cancer stem-like cells and high-grade oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 14, 4085–4095, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-4404 (2008).

Fu, T. Y. et al. Association of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG expression with oral squamous cell carcinoma progression. Journal of oral pathology & medicine: official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology 45, 89–95, doi: 10.1111/jop.12335 (2016).

Ge, N. et al. Prognostic significance of Oct4 and Sox2 expression in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of translational medicine 8, doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-94 (2010).

Hayry, V. et al. Bmi-1 expression predicts prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. British journal of cancer 102, 892–897, doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605544 (2010).

Huber, G. F. et al. Expression patterns of Bmi-1 and p16 significantly correlate with overall, disease-specific, and recurrence-free survival in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 117, 4659–4670, doi: 10.1002/cncr.26100 (2011).

Lee, H. J. et al. Positive expression of NANOG, mutant p53, and CD44 is directly associated with clinicopathological features and poor prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC oral health 15, 153, doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0120-9 (2015).

Li, C. Study on Expression of OCT4 and BIRC5 and Molecular mechanisms of Their Dual-shRNA-induced Apoptosis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Chinese). Diss. Second Military Medical University (2012).

Li, X. J. et al. Expression of Oct4 and its prognostic significance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma(Chinese). Chin J Cancer Prev Treat 20, 753–756 (2013).

Li, X. J. et al. Expression of Nanog and its prognostic significance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma(Chinese). Chin J Cancer Prev Treat 21, 1962–1965 (2014).

Li, Z. W. et al. Oncogenic roles of Bmi1 and its therapeutic inhibition by histone deacetylase inhibitor in tongue cancer. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 94, 1431–1445, doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.123 (2014).

Liu, W. L. et al. Prognostic relevance of Bmi-1 expression and autoantibodies in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC cancer 10, doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-467 (2010).

Luo, W. et al. Embryonic stem cells markers SOX2, OCT4 and Nanog expression and their correlations with epithelial-mesenchymal transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PloS one 8, e56324, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056324 (2013).

Ravindran, G., Sawant, S. S., Hague, A., Kingsley, K. & Devaraj, H. Association of differential beta-catenin expression with Oct-4 and Nanog in oral squamous cell carcinoma and their correlation with clinicopathological factors and prognosis. Head & neck 37, 982–993, doi: 10.1002/hed.23699 (2015).

Song, L. B. et al. Bmi-1 is a novel molecular marker of nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression and immortalizes primary human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Cancer research 66, 6225–6232, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-0094 (2006).

Tang X. et al. The expression of stem cell transcription factor SOX2 and OCT4 in laryngeal carcinoma and its relationship with prognosis(Chinese). Journal of practical medicine 29, 751–753 (2013).

Yamazaki, H. et al. Stem cell self-renewal factors Bmi1 and HMGA2 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: clues for diagnosis. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 93, 1331–1338, doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.120 (2013).

Ventela, S. et al. CIP2A is an Oct4 target gene involved in head and neck squamous cell cancer oncogenicity and radioresistance. Oncotarget 6, 144–158 (2015).

Yu, M. Reaserch on the expression of Podoplanin, Bmi-1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and its clinical significance(Chinese). Diss. Luzhou Medical College (2013).

Yu, L. et al. Clinicopathological significance of cancer stem cells marked by CD133 and KAI1/CD82 expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. World journal of surgical oncology 12, 118, doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-118 (2014).

Wells, G. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute Web site. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (2012).

Yuan, B. et al. Prognostic Value and Clinicopathological Differences of Bmi1 in Gastric Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 16, 407–413 (2016).

Qu, H., Li, R., Liu, Z., Zhang, J. & Luo, R. Prognostic value of cancer stem cell marker CD133 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 6, 2644–2650 (2013).

Zhou, Q. et al. Prognostic value of cancer stem cell marker CD133 in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine 8, 3080–3088 (2015).

Wen, L. et al. Prognostic value of cancer stem cell marker CD133 expression in gastric cancer: a systematic review. PloS one 8, e59154, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059154 (2013).

Zhong, C., Wu, J., Fang, M. & Pu, L. Clinicopathological significance and prognostic value of the expression of the cancer stem cell marker CD133 in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Tumor Biology 36, 7623–7630, doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3487-y (2015).

Chiou, S. H. et al. Coexpression of Oct4 and Nanog enhances malignancy in lung adenocarcinoma by inducing cancer stem cell-like properties and epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation. Cancer research 70, 10433–10444, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2638 (2010).

Yin, X. et al. Coexpression of gene Oct4 and Nanog initiates stem cell characteristics in hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through activation of Stat3/Snail signaling. Journal of hematology & oncology 8, 23, doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0119-3 (2015).

Parmar, M. K., Torri, V. & Stewart, L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Statistics in medicine 17, 2815–2834 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81371148 and 81671000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B. and X.J. designed this review; F.Z.N. and L.M.X. searched the databases and inspected all candidate articles; C.X.B. and W.J. extracted the data; L.X.Y. and W.H.F. assessed the quality of included studies by the NOS; X.J. and W.Z. provided statistical advice and F.Z.N. and L.M.X. analyzed the data; C.B. checked the accuracy of the statistical analyses; F.Z.N., L.M.X. and C.X.B. wrote the manuscript, and all authors reviewed the manuscript critically.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Z., Li, M., Chen, X. et al. Prognostic Value of Cancer Stem Cell Markers in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: a Meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7, 43008 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43008

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43008

This article is cited by

-

Molecular mechanism(s) of regulation(s) of c-MET/HGF signaling in head and neck cancer

Molecular Cancer (2022)

-

Role of cancer stem cell markers ALDH1, BCL11B, BMI-1, and CD44 in the prognosis of advanced HNSCC

Strahlentherapie und Onkologie (2021)

-

The role of CD133 expression of cancer stem cells on radiotherapy response in early stage glottic cancers

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2020)

-

DSPP-MMP20 gene silencing downregulates cancer stem cell markers in human oral cancer cells

Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters (2018)

-

A subtype of cancer-associated fibroblasts with lower expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin suppresses stemness through BMP4 in oral carcinoma

Oncogenesis (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.