Abstract

This anatomical study sought to investigate the morphological characteristics and biomechanical properties of the oblique popliteal ligament (OPL). Embalmed cadaveric knees were used for the study. The OPL and its surrounding structures were dissected; its morphology was carefully observed, analyzed and measured; its biomechanical properties were investigated. The origins and insertions of the OPL were relatively similar, but its overall shape was variable. The OPL had two origins: one originated from the posterior surface of the posteromedial tibia condyle, merged with fibers from the semimembranosus tendon, the other originated from the posteromedial part of the capsule. The two origins converged and coursed superolaterally, then attached to the fabella or to the tendon of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius and blended with the posterolateral joint capsule. The OPL was classified into Band-shaped, Y-shaped, Z-shaped, Trident-shaped, and Complex-shaped configurations. The mean length, width, and thickness of the OPL were 39.54, 22.59, and 1.44 mm, respectively. When an external rotation torque (18 N·m) was applied both before and after the OPL was sectioned, external rotation increased by 8.4° (P = 0.0043) on average. The OPL was found to have a significant role in preventing excessive external rotation and hyperextension of the knee.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oblique popliteal ligament (OPL) is the largest structure on the posterior aspect of the knee, and given its broad shape, it is probably vulnerable to, or easily involved in, posterior knee injuries1. However, current surgical reconstruction procedures usually ignore potential tears of the OPL, thus inducing an inability to reproduce native dynamic knee function1,2. Insufficient awareness of the anatomic characteristics, radiographic features, and biomechanical properties of the OPL may result in a failure to recognize and replicate normal anatomical structures and functional rehabilitation in the management of traumatic injuries to the knee joint. Thus, a combined anatomical and biomechanical study of the OPL would contribute to “rediscovery” of the posterior structures and corresponding function of the knee, thereby providing a more anatomical and functional basis for the treatment of OPL injuries.

Several investigators have attempted to explore the characteristics of the OPL1,2,3,4,5. However, descriptions of the morphology and role of the OPL in the knee joint remain inconsistent in the literature. Some textbooks and articles3,4,5 report that the OPL originates with the tendon of the semimembranosus muscle, whereas other sources have described that the OPL is formed by a confluence of the lateral expansion of the semimembranosus tendon and the capsular arm of the posterior oblique ligament1,6,7. The course of the OPL is fairly similar, and its terminal attachments are relatively uniform, but the description of its arms or attachments is variable. Furthermore, there remains a paucity of data describing the external features, anatomical characteristics, and biomechanical properties of the OPL.

It has also been reported that the OPL is a primary ligament restraint to knee hyperextension2,8. However, on the basis of the oblique course of the OPL and the Parallelogram of Force (Fig. 1)9, we deduce that the OPL not only has the function of preventing hyperextension, but also plays a significant role in preventing excessive external knee rotation. Therefore, given the contradictions and limitations found in the literature, it is necessary to perform further study of the anatomical and biomechanical characteristics of the OPL, which would contribute to the recognition and restoration of OPL injuries and would help surgeons avoid iatrogenic injuries.

The purpose of the present study was twofold. First, this study attempted to provide a detailed description of the anatomical structures and to complement the quantitative data on the OPL in the Asian population. Second, our study sought to characterize the biomechanical properties and to provide a comprehensive analysis of the primary function of the OPL.

Results

Anatomy of the OPL

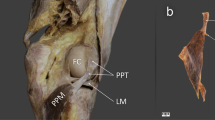

The OPL was identified in all specimens as a broad and flat ligament that diagonally crossed the posterior knee joint and overlaid the posterior surface of the knee joint capsule. The OPL was a well-defined ligament that crossed superficially from the posteromedial aspect of the capsule and attached to the posterolateral corner of the knee. In each knee pair in our study, the morphology of the OPL was roughly symmetrical bilaterally. The OPL originated from the posterior surface of the posteromedial tibial plateau and blended with fibers from the semimembranosus tendon (Fig. 1). Additionally, some fibers from the posteromedial part of the capsule blended with the OPL and formed a secondary medial origin. The two origins merged and coursed superolaterally, then attached to the fabella or to the tendon of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius (if there was no bony fabella), blending into the posterior capsule over the lateral femoral condyle.

Additionally, the middle genicular neurovascular bundle entered the midsection of the OPL and passed through elliptical-shaped holes in the posterior joint capsule to supply the cruciate ligaments and synovial membrane (Fig. 1). In our specimens, 11 pairs of 15 had two obvious holes, and the other four pairs had one hole. The shapes of the holes varied from ellipsoid to a long ellipse. The major axes of the elliptic holes were parallel with the courses of the OPL. Different shapes and entry points of the neurovascular holes divided the OPL into two (in 10 pairs of 15) or three (in 5 pairs of 15) bundles.

The origins and final insertions of the OPL were relatively stable, but there was significant variability in the attachments and shapes of the OPL. The most frequent branch was the tibial expansion of the OPL. The tibial expansion originated from the posterolateral corner of the knee and ran almost vertically downward, then attached to the tibia. The tibial expansion of the OPL was palpable in 7 pairs of 15, some of which were thin (2 pairs of 7), but most of which were thick and tough (5 pairs of 7). At the middle and distal part of the OPL, there were sparse fibers that attached at the upper margin of the intercondylar fossa and the posterior surface of the femur. The insertion of the OPL also blended with the fibers of the fabellofibular ligament.

Furthermore, we classified the OPL into five types according to the current external features of the OPL (Fig. 2): Band-shaped (5 pairs), Y-shaped (4 pairs), Trident-shaped (3 pairs), Z-shaped (2 pairs), and Complex-shaped (1 pair). The Band-shaped OPL did not have attachments to the tibia, and the two origins did not have an obvious separation; thus, it was stripe-shaped like a band (Figs 2 and 3). The Y-shaped OPL had two obvious separate origins: one originating from the medial tibial plateau and blending with semimembranosus tendon, and the other originating from the posteromedial part of the capsule (Figs 2, 4, 5 and 6). The Z-shaped OPL obtained its name mainly on the basis of two slender ellipses parallel to the three separate bundles (Figs 2, 7 and 8). The Trident-shaped OPL had two distinct origins and one main central tibial expansion of the OPL (Figs 2, 9 and 10). Finally, the Complex-shaped OPL was relatively uncommon and included double tibial expansions, sparse fibers attached to the margin of the intercondylar fossa, and a fiber bundle to the tendon of the plantaris muscle (Figs 2 and 11).

The mean length of the OPL was 39.54 ± 4.64 mm, but the ligament width was more variable. The average width at the midpoint was 22.59 ± 5.09 mm at the midpoint, and the average thickness at the midpoint was 1.44 ± 0.40 mm. The mean angle between the OPL and the joint line was 29.78 ± 2.62°.

Biomechanical properties

When we performed the hyperextension experiment, we observed that the OPL and tibial expansion of the OPL became tensioned, thus indicating its function in preventing knee hyperextension. When the flexion angle was set to 45° and a rotational torque was applied on the tibia, the tibia externally rotated and the OPL was qualitatively observed to be taut. The intact state external rotation angle averaged 20.2°; after the OPL was sectioned and the same rotational torque was applied, the average increase in tibial external rotation was 8.4° (P = 0.0043).

Discussion

The purpose of this descriptive laboratory study was to explore the anatomical characteristics and biomechanical properties of the OPL. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to date to describe the morphology of the OPL in detail and to classify the shape of the OPL into different types. Furthermore, we also performed a biomechanical analysis to demonstrate that the OPL plays significant roles in preventing both excessive external knee rotation and knee hyperextension, thus validating the structural properties of the OPL in providing stability to the human knee. Notably, this is also the first study to report on the size parameters of the OPL in the Chinese population.

The anatomic characteristics and biomechanical properties of the OPL have been recognized for a long time10,11,12,13. However, with the rapid development of sports medicine, the key stabilizing elements of the knee have recently been rediscovered1,2,4,14,15,16,17. Customarily, these studies have dissected and described the anatomy of fresh-frozen human cadaveric knees and conducted quantitative biomechanical experiments1,2,3,4,18,19,20,21. Although these explorations1,2,3,5 have described the shape and parameters of the OPL and have provided quantitative biomechanics, which have contributed to a better understanding of the role of the OPL in preventing knee hyperextension2, the diversity of the morphology of the OPL has rarely been reported to date, and its function of preventing excessive external rotation of the knee was neglected in studies.

It is unknown whether prenatal heredity, postnatal development, or both cause the various OPL shapes. We infer that the different types of OPL would produce slight differences in knee stability when they are injured. Compared with the Band-shaped OPL, the origin of the Y-shaped OPL was divaricate, thereby contributing to resolving the bearing strength of the OPL. Compared with the Y-shaped OPL, the most prominent characteristic of the Z-shaped OPL was its division into bundles, thus reciprocally spreading the force among the bundle bands. The Trident-shaped and Complex-shaped OPL had multiple attachments and arms, thus making it easier to spread force to the surrounding structures; the unfavorable consequence of such a divaricate structure is that it may be more vulnerable and easily damaged or involved in peripheral injuries. Additional research is warranted to explore exactly how the force is resolved from the trunk of the ligament to these multiple insertions or attachments. Such knowledge would contribute to understanding and predicting the individual impaired segments.

The average length of the OPL in our study was approximately 39.54 ± 4.64 mm, which was shorter than the 48.0 mm (range, 43.0–55.0) reported by LaPrade et al.1 and 45.56 ± 4.67 mm reported by Osti et al.4, but longer than the 33.6 ± 4.8 mm reported by Fam et al.3. The mean angle between the OPL and the horizontal joint line in our study was 29.78 ± 2.62°, which was smaller than the 32.2 ± 6.6° reported by Fam et al.3. These differences may be primarily attributed to different methods of measurement; another potential explanation is ethnic differences, although this possibility is uncertain, owing to limited data.

The OPL is an important stabilizing structure on the posterior aspect of the knee joint, and it also provides an important reinforcing function in joint stability. However, its biomechanical characteristics together with its structural properties, have not been well recognized. Although a previous study has reported its role in preventing knee hyperextension11, a recent in-depth study applying a sequential sectioning technique on the major structures of the posterior knee has found that the OPL is the primary ligamentous restraint to knee hypertension, thus highlighting the biomechanical importance of the OPL2. Similarly, both the “posterolateral corner” and the “posteromedial corner” resist tibial rotation22, yet a main primary stabilizer against excessive external knee rotation has not been well identified and requires further exploration.

Because of the diagonal oblique course of the OPL, the forces along it could be separated into a horizontal force and a vertical force (Fig. 1); it is therefore logical, that the horizontal force can prevent excessive external rotation and the vertical force can prevent hyperextension. The horizontal force was greater than the vertical force according to the angle down from the horizontal joint line, thus possibly indicating that preventing excessive external knee rotation is a relatively more important function of this structure. In extreme cases (Figs 6 and 7), the OPL was horizontally located in the posterior aspect of the knee, thus highlighting its unique function in preventing excessive external knee rotation. Moreover, the neurovascular apertures on the OPL were generally elliptical, and the long shaft paralleled the course of the main OPL trunk, a result that may indicate flexible margins of the OPL. Thus, the biomechanical function of the OPL appears to be preventing both excessive external knee rotation and knee hyperextension. When the knee joint moves from flexion to extension, there would be an accompanied tibial axial external rotation23,24,25,26, and the OPL provides stability in hyperextension and axial rotation in normal activities, extreme sports, and serious trauma.

The knee is one of the largest and most complex pivotal hinge joints in the body. The patella and patellar ligament and four key ligaments of the knee including the anterior/posterior cruciate ligaments and the medial/lateral (fibular) collateral ligaments are responsible for the anterior, medial, and lateral stability of the knee joint; however, the posterior aspect of the knee is relatively feeble. Another important function of the OPL is to reinforce the posterior knee capsule, which together with other ligaments forms a circumferential sleeve around the knee, thus providing stability to the knee overall. Even so, there remains an area without external support between the OPL, the expansion over the popliteus muscle, and the lateral side of the posterior cruciate ligament, which are strongly related to the formation of popliteal cysts27,28,29. The elliptical holes in the OPL (Figs 3,4,7 and 8) are also weak areas and may be associated with popliteal cyst formation30. Therefore, the morphology and attachments of the OPL may influence the formation of popliteal cysts to some extent.

The tibial expansion of the OPL that belongs to the posterolateral corner of the knee has been reported to strengthen the knee in hyperextension31. Attention should be focused on preventing iatrogenic injuries to the OPL, especially to the tibial expansion, during a posterior approach to the knee32. Damage to the OPL or the tibial expansion of the OPL can be debilitating to patients and may require prompt recognition and treatment to avoid long-term consequences33. If there is posterolateral instability of the knee or in planning for surgical intervention, the involvement and biomechanical function of the OPL should be considered.

Injuries to the posterior aspect of the knee, especially the posterolateral corner, are common21,34. It has not been well studied whether the OPL attachments are involved in these injuries. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans should be recommended to evaluate injury to the OPL or its attachments35,36,37,38,39.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, because it was difficult to obtain fresh-frozen cadaveric knees in our institute, we had to utilize specimens fixed with formalin in our experiment. This issue probably had no effect on the description of the shape of the OPL and its classification; however, the biomechanical testing data may have been strongly influenced. Nonetheless, as mentioned previously, we were still able to demonstrate its function in preventing excessive external knee rotation and hyperextension. Second, the self-designed tensile testing instrument did not have a high-precision measurement tool; however, it was adequate for this experiment.

Conclusion

The medial and lateral attachments of the OPL were relatively consistent, but its course and structure were variable and were classified into types on the basis of its shape. The OPL plays significant roles in preventing both excessive external knee rotation and hyperextension and in strengthening the stability of the knee. Improved recognition of the OPL may help define its involvement in posterior knee injuries and the consequences of damaging this ligament during posterior knee surgery.

Materials and Methods

Specimen information

This descriptive laboratory study used 15 pairs of embalmed cadaveric knee specimens from 11 male and 4 female Chinese donors. Knees with damaged posterior structures, a history of injury or surgery, cachexia, ligamentous injury, or indications of osteoarthritis were excluded. The average age of the donors at the time of death was 62.7 years (range, 49–76). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chongqing Medical University. All methods and procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations40. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Anatomy dissection

Preparation, detailed dissection, and sectioning of the knees were performed according to a standardized procedure. The dissection was performed by means of posterior access. A gross anatomic dissection was performed to completely remove the skin and subcutaneous tissues around the knee. Next, precise dissection of the posterior structures of the knee was performed to identify the deep layers. We removed the neurovascular bundle to ensure sufficient exposure and to improve visualization. The dissections consisted of identification of the deep layer of the knee which was located between the posterior borders of the semimembranosus and the tibial course of the superficial medial collateral ligament medially, and the medial border of the long head of the biceps femoris and fibula laterally. All relative structures anterior (deep) to the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus were preserved and identified. The OPL was then isolated and cleared of residual tissues, the origins were dissected, and the attachments were identified. The OPL and the structures confluent with it were also dissected, carefully observed, recorded, and measured. Additionally, the morphology of the OPL was classified into types according to the external features on the basis of its shape.

Quantitative analysis

Characteristics of the OPL and its orientation relative to the surrounding structures were recorded after OPL identification. The size of the OPL was measured to provide supplemental data about the OPL in the Chinese population. To perform the measurements, needles were used to identify the precise origin and insertion points and bony landmarks, and then the OPL was measured with a Vernier caliper with a reported measurement accuracy to 0.02 mm (JiangHua, Shanghai, China). The length was measured by taking the distance from the origin of the major structures of the OPL to the selected osseous landmarks (the midportion of the capsule on the femur distally). The width and thickness of the OPL were gauged at the midpoint of the OPL. The angle between the OPL and the horizontal joint line was measured with Image-Pro Plus version 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). The measured data were reported as the means with standard deviations (SD), which were calculated using the appropriate t-score with SAS software, version 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Biomechanical testing

Biomechanical characteristics of the OPL were tested using a self-designed tensile testing instrument (Fig. 12a–c). The instrument was composed of three parts: a mounting bracket, a torsion apparatus, and a circular scale (measurement accuracy 0.1°) with a pointer. The mounting bracket provided fixation of the femur and tibia and was simultaneously used to regulate the angle between the femur and tibia. The torsion apparatus was mainly used to apply torque (measurement accuracy 0.5 N·m) on the tibia, with the torque arising from a pair of unequal and equidirectional forces. A large-diameter lightweight sheave was bound and rotated together with the tibia; another strap was wrapped around the sheave for several coils; and each end of the strap was tied to unequal weights, thus generating a constant vertical downward torque. The sheave transmitted the torque to the tibia simultaneously. The circular scale fixed at the terminus of the tibia also rotated together with the tibia, and a stationary pointer reported the rotation angle. To verify the restraint effect of hyperextension, we applied a hyperextension force (Fig. 12d) and to qualitatively observe its function and confirm the results of previous studies2. To determine whether the OPL plays a role in preventing excessive external knee rotation, before and after sectioning was performed, we rigidly anchored the distal end of the femur and set the flexion angle to 45° (Fig. 12e,f). A rotational torque (18 N·m) was applied to the tibia to induce external rotation of the lower limb, and the rotation angle was measured and recorded. The OPL was then sectioned; the same rotational torque was applied; and the rotation angle was measured and recorded again. All anatomical and biomechanical measurements are reported as mean values.

(a) Illustration of our self-designed testing apparatus (front view): the circular scale (measurement accuracy 0.1°) with a pointer was fixed at the terminal of the tibia and rotated together with the tibia; (a) large-diameter lightweight sheave was wrapped around for several coils with (a) strap, and each end of the strap was tied to unequal weights that generated a constant vertical downward torque. (b) Illustration of our self-designed testing apparatus (lateral view): the large-diameter lightweight sheave was bound and rotated together with the tibia, and the sheave transmitted the torque to the tibia simultaneously; the femur was fixed on the mounting bracket; and the tibia rotated in the sleeve. (c) Illustration of our self-designed testing apparatus (oblique view): the angle between the femur and tibia could be regulated. (d) Illustration of verifying the restraint effect of hyperextension: the posterior knee was upward, and we applied a hyperextension force to qualitatively observe and verify its function. (e) Illustration of testing the effect of preventing excessive external knee rotation: the strap was tied to unequal weights and generated a constant vertical downward torque. (f) Illustration of testing the effect of preventing excessive external knee rotation: the tibia appeared to rotate counterclockwise, and the rotation angel before and after sectioning the oblique popliteal ligament was measured and recorded.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wu, X.-D. et al. Anatomical Characteristics and Biomechanical Properties of the Oblique Popliteal Ligament. Sci. Rep. 7, 42698; doi: 10.1038/srep42698 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10 April 2017

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

10 April 2017

Scientific Reports 7: Article number: 42698; published online: 16 February 2017; updated: 10 April 2017 This Article contains an error in the Discussion section. “Even so, there remains an area without external support between the OPL, the expansion over the popliteus muscle, and the lateral side ofthe posterior cruciate ligament, which are strongly related to the formation of popliteal cysts”.

References

LaPrade, R. F., Morgan, P. M., Wentorf, F. A., Johansen, S. & Engebretsen, L. The anatomy of the posterior aspect of the knee. An anatomic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89, 758–764 (2007).

Morgan, P. M., LaPrade, R. F., Wentorf, F. A., Cook, J. W. & Bianco, A. The role of the oblique popliteal ligament and other structures in preventing knee hyperextension. Am J Sports Med 38, 550–557 (2010).

Fam, L. P. D. A. et al. Oblique popliteal ligament-an anatomical study. Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia (English Edition) 48, 402–405 (2013).

Osti, M., Tschann, P., Künzel, K. H. & Benedetto, K. P. Posterolateral corner of the knee: microsurgical analysis of anatomy and morphometry. Orthopedics 36, e1114–20 (2013).

Hedderwick, M. The anatomy of the oblique popliteal ligament (Thesis, Master of Science). University of Otago. (available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10523/2359) (2012)

Hughston, J. C., Andrews, J. R., Cross, M. J. & Moschi, A. Classification of knee ligament instabilities. Part I. The medial compartment and cruciate ligaments. J Bone Joint Surg Am 58, 159–172 (1976).

Rossi, R. (Ed.) Knee ligament injuries: extraarticular surgical techniques. Springer. (2014).

Brantigan, O. C. & Voshell, A. F. The mechanics of the ligaments and menisci of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg 23, 44–66 (1941).

Routh, E. J. A treatise on analytical statics. Cambridge University Press (1896).

Abbott, L. C., John, B., Saunders, M., Bost, F. C. & Anderson, C. E. Injuries to the ligaments of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg 26, 503–521 (1944).

Kaplan, E. B. The fabellofibular and short lateral ligaments of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 43, 169–179 (1961).

Warren, L. F. & Marshall, J. L. The supporting structures and layers on the medial side of the knee: an anatomical analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 61, 56–62 (1979).

Welsh, R. P. Knee joint structure and function. Clin Orthop Relat Res 147, 7–14 (1980).

Vincent, J. P. et al. The anterolateral ligament of the human knee: an anatomic and histologic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20, 147–52 (2012).

Claes, S. et al. Anatomy of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. J Anat 223, 321–328 (2013).

Dodds, A. L., Halewood, C., Gupte, C. M., Williams, A. & Amis, A. A. The anterolateral ligament: Anatomy, length changes and association with the Segond fracture. Bone Joint J 96-B, 325–331(2014).

Kennedy, M. I. et al. The anterolateral ligament: an anatomic, radiographic, and biomechanical analysis. Am J Sports Med 43, 1606–1615 (2015).

Veltri, D. M., Deng, X. H., Torzilli, P. A., Warren, R. F. & Maynard, M. J. The role of the cruciate and posterolateral ligaments in stability of the knee. A biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med 23, 436–443 (1995).

Moorman, C. T. 3rd & LaPrade, R. F. Anatomy and biomechanics of the posterolateral corner of the knee. J Knee Surg 18, 137–145 (2005).

Maynard, M. J., Deng, X., Wickiewicz, T. L. & Warren, R. F. The popliteofibular ligament. Rediscovery of a key element in posterolateral stability. Am J Sports Med 24, 311–316 (1996).

Kawano, C. T., Bispo, R. Z. Jr, de Oliveira, M. G., Soejima, A. T. & Apostolopoulos, S. B. Posterolateral knee instability: an alternative proposal for surgical treatment. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 62, 371–374 (2007).

Vinson, E. N., Major, N. M. & Helms, C. A. The posterolateral corner of the knee, AJR Am J Roentgenol 190, 449–458 (2008).

Margareta, N. & Victor, H. F. Basic biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system 3rd. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (2001).

Shoemaker, S. C. & Markolf, K. L. In vivo rotatory knee stability. Ligamentous and muscular contributions. J Bone Joint Surg Am 64, 208–216 (1982).

Wang, C. J. & Walker, P. S. Rotatory laxity of the human knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 56, 161–170 (1974).

Matsumoto, H., Seedhom, B. B., Suda, Y., Otani, T. & Fujikawa, K. Axis location of tibial rotation and its change with flexion angle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 371, 178–182 (2000).

Johnson, L. L., van, Dyk, G. E., Johnson, C. A., Bays, B. M. & Gully, S. M. The popliteal bursa (Baker’s cyst): an arthroscopic perspective and the epidemiology. Arthroscopy 13, 66–72 (1997).

Labropoulos, N., Shifrin, D. A. & Paxinos, O. New insights into the development of popliteal cysts. Br J Surg 91, 1313–1318 (2004).

Calvisi, V., Lupparelli, S. & Giuliani, P. Arthroscopic all-inside suture of symptomatic Baker’s cysts: a technical option for surgical treatment in adults. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 15, 1452–1460 (2007).

Takahashi, M. & Nagano, A. Arthroscopic treatment of popliteal cyst and visualization of its cavity through the posterior portal of the knee. Arthroscopy 21, 638 (2005).

Terry, G. C. & LaPrade, R. F. The posterolateral aspect of the knee Anatomy and surgical approach. Am J Sports Med 24, 732–739 (1996).

Park, S. E., Stamos, B. D., DeFrate, L. E., Gill, T. J. & Li, G. The effect of posterior knee capsulotomy on posterior tibial translation during posterior cruciate ligament tibial inlay reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 32, 1514–1519 (2004).

LaPrade, R. F., Ly, T. V., Wentorf, F. A. & Engebretsen, L. The posterolateral attachments of the knee: a qualitative and quantitative morphologic analysis of the fibular collateral ligament, popliteus tendon, popliteofibular ligament, and lateral gastrocnemius tendon. Am J Sports Med 31, 854–860 (2003).

Geiger, D., Chang, E. Y., Pathria, M. N. & Chung, C. B. Posterolateral and posteromedial corner injuries of the knee. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 22, 581–599 (2014).

Recondo, J. A. et al. Lateral stabilizing structures of the knee: functional anatomy and injuries assessed with MR imaging. Radiographics 20 Spec No, S91–S102 (2000).

Beltran, J. et al. The distal semimembranosus complex: normal MR anatomy, variants, biomechanics and pathology. Skeletal Radiol 32, 435–445 (2003).

Munshi, M. et al. MR imaging, MR arthrography, and specimen correlation of the posterolateral corner of the knee: an anatomic study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 180, 1095–1101 (2003).

Chahal, J., Al-Taki, M., Pearce, D., Leibenberg, A. & Whelan, D. B. Injury patterns to the posteromedial corner of the knee in high-grade multiligament knee injuries: a MRI study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18, 1098–104 (2010).

Lundquist, R. B. et al. Posteromedial Corner of the Knee: The Neglected Corner. Radiographics 35, 1123–37 (2015).

Guidelines for anatomical examinationhttp://www.anatsoc.org.uk/education/guidelines/the-guidelines (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Hu-Qin Zhang, Yuan Zhong, Human Gross Morphology Lab, National Class Preclinical Medicine Experimental Teaching Demonstration Center, Chongqing Medical University, for their help in preparing the cadaveric specimens. We also gratefully thank the individuals (as well as their family members’ understanding and agreement) who generously donated their bodies for research and education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: Shan-Quan Sun, Xiang-Dong Wu. Performed experiments: Xiang-Dong Wu, Jin-Hui Yu, Tao Zou, Wei Wang. Acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data: Xiang-Dong Wu, Robert F. LaPrade, Wei Huang, Shan-Quan Sun. Drafted or revised the article: Xiang-Dong Wu, Robert F. LaPrade, Jin-Hui Yu, Tao Zou, Wei Wang, Wei Huang, Shan-Quan Sun. Final approval of the version to be published: Xiang-Dong Wu, Jin-Hui Yu, Tao Zou, Wei Wang, Robert F. LaPrade, Wei Huang, Shan-Quan Sun.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, XD., Yu, JH., Zou, T. et al. Anatomical Characteristics and Biomechanical Properties of the Oblique Popliteal Ligament. Sci Rep 7, 42698 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42698

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42698

This article is cited by

-

Morphological and morphometric analysis of oblique popliteal ligament in North Indian population: a cadaveric study

Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy (2024)

-

The prevalence and parameters of fabella and its association with medial meniscal tear in China: a retrospective study of 1011 knees

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2022)

-

Acute primary repair of extraarticular ligaments and staged surgery in multiple ligament knee injuries

Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology (2020)

-

An anomalous band originating from the fabella causing semimembranosus impingement presenting as knee pain: a case report

Journal of Medical Case Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.