Abstract

A novel process for the preparation of aggregate-free metal oxide nanopowders with spherical (0D) and non-spherical (1D) hollow nanostructures was introduced. Carbon nanofibers embedded with iron selenide (FeSe) nanopowders with various nanostructures are prepared via the selenization of electrospun nanofibers. Ostwald ripening occurs during the selenization process, resulting in the formation of a FeSe-C composite nanofiber exhibiting a hierarchical structure. These nanofibers transform into aggregate-free hollow Fe2O3 powders via the complete oxidation of FeSe and combustion of carbon. Indeed, the zero- (0D) and one-dimensional (1D) FeSe nanocrystals transform into the hollow-structured Fe2O3 nanopowders via a nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process, thus conserving their overall morphology. The discharge capacities for the 1000th cycle of the hollow-structured Fe2O3 nanopowders obtained from the FeSe-C composite nanofibers prepared at selenization temperatures of 500, 800, and 1000 °C at a current density of 1 A g−1 are 932, 767, and 544 mA h g−1, respectively; and their capacity retentions from the second cycle are 88, 92, and 78%, respectively. The high structural stabilities of these hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders during repeated lithium insertion/desertion processes result in superior lithium-ion storage performances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hollow nanopowders with controlled size and morphology have wide applications in various fields, such as rechargeable batteries, hydrogen evolution reactions, gas sensors, catalysis, and drug delivery1,2,3,4,5,6,7. To date, zero- (0D), one- (1D), two- (2D), and three-dimensional (3D) hollow nanostructures with various compositions have been developed based on the requirements of the various applications8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Generally, spherical (0D) and non-spherical (1D, 2D, and 3D) hollow nanostructures are prepared by the application of removable organic and inorganic templates in liquid solution processes13,14,15,16,17. For example, organic polymers such as polystyrene (PS) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), in addition to silica nanopowders have been widely used as sacrificial templates for hollow nanospheres (0D), as they can be easily removed, and their size can be easily controlled18,19,20.

Recently, nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion and Ostwald ripening processes, in which filled structures are transformed into hollow structures during heat treatment, have been applied in the preparation of hollow nanospheres (0D) in the absence of templates21,22,23,24,25. More specifically, metal nanospheres embedded within amorphous carbon and reduced graphene oxide were transformed into their corresponding oxide and selenide hollow nanospheres during the heat treatment stage of the nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process26,27,28,29. However, controlling the metal oxide nanopowder dimensions through the oxidation of metallic nanopowders was challenging. Thus, to date, a simple and general process for the control of hollow nanostructure dimensions has not yet been developed. In addition, the preparation of aggregate-free metal oxide nanopowders via an electrospinning process has received little attention. Furthermore, the application of metal selenide nanomaterials with various morphological characteristics for the formation of hollow structured nanomaterials via the nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process has yet to be examined in detail.

Nanostructured Fe2O3 materials including hollow spheres, core-branch arrays, nanosheets, and graphene hybrids have been extensively studied as the anode material for LIBs due to their high capacity, natural abundance, and environmental benignity30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Chen et al. synthesized aligned Fe2O3 nanotubes by a templating technique and proved their feasibility in anode materials for LIBs36. Lou et al. fabricated single-crystal Fe2O3 nanodiscs and microparticles containing porosity via a controlled H2C2O4 etching process37. Particles with higher porosity showed superior capacity retention due to effective buffering of volume changes during repetitive cycling.

Thus, we herein investigate the nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process for the preparation of metal oxide nanopowders with hollow nanostructures of equal compositions but different dimensions (i.e., 0D and 1D). No additional surfactants or sacrificial templates were required using our procedure. Carbon nanofibers embedded with metal selenide nanopowders exhibiting nanostructures of different dimensions were prepared via selenization of the electrospun nanofibers. A subsequent oxidation process under air produced the desired aggregate-free metal oxide nanopowders via the nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process. Finally, the morphological and electrochemical properties of the iron oxide (Fe2O3) nanopowders, which were selected as the initial target material, were systematically studied.

Results and Discussion

Figure 1 outlines the mechanism of the formation of Fe2O3 nanopowders exhibiting hollow nanostructures of different dimensions via the nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process. Following the selenization processes at different temperatures (i.e., 500, 800, or 1000 °C), the electrospun nanofibers (Fig. 1-①) were transformed into the hierarchical nanostructures. Selenization of the iron components located close the nanofiber surface resulted in the formation of FeSe nanocrystals during the early stages of the process. Ostwald ripening then occurred during further selenization to yield the hierarchical FeSe-C composite nanofiber. In this process, the ultrafine FeSe nanocrystals formed inside the carbon nanofiber diffused to the surface to produce FeSe crystals via Ostwald ripening. Complete selenization at 500 °C resulted in the carbon nanofiber being uniformly embedded with ultrafine FeSe nanocrystals (Fig. 1-②). However, at higher selenization temperatures (Fig. 1-③), crystal growth occurred via the segregation of nanocrystals and spheroidization due to melting. Finally, the hierarchical FeSe-C nanofibers transformed into hollow aggregate-free Fe2O3 nanopowders (Fig. 1-④ and 1-⑤) via the complete combustion of carbon and oxidation of FeSe. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 2, FeSe nanocrystals with 0D and 1D structures transformed into the hollow-structured Fe2O3 nanopowders via a nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process, thus conserving their overall morphology. For simplicity, the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders obtained from the FeSe-C composite nanofibers prepared at 500, 800, and 1000 °C are referred to as “Sel.500-Oxi.600,” “Sel.800-Oxi.600,” and “Sel.1000-Oxi.600,” respectively.

The mechanism of formation of the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders with 1D (Fig. 2a) and 0D structures (Fig. 2b) was investigated based on the morphologies and crystal structures of the materials obtained in each step. The morphologies and crystal structures of the electrospun nanofibers stabilized at 120 °C under air are shown in Figure S1. The nanofibers exhibited a clean surface structure and an amorphous-like crystal structure with small Fe3O4 crystalline peaks, and transformed into the desired hierarchical structured nanofibers following selenization at 500, 800, and 1000 °C, as shown in Fig. 3. During this selenization process, the carbonization of PAN resulted in the formation of carbon nanofibers. As confirmed by XRD studies (Figure S2), the nanocrystals decorated on the carbon nanofiber surfaces were iron selenide (FeSe). Interestingly, although the composite nanofibers obtained at a selenization temperature of 500 °C exhibited a pure hexagonal FeSe phase, those obtained at 800 and 1000 °C exhibited mixed hexagonal FeSe and tetragonal FeSe crystal structure phases. As outlined previously (Fig. 1), FeSe nanocrystals formed over the carbon nanofibers during the Ostwald ripening process. Indeed, following selenization at 500 °C, rod-like FeSe nanocrystals were obtained, as shown in the SEM images of the FeSe-C composite nanofibers provided in Fig. 3a. However, at higher temperatures (i.e., 800 °C), a number of FeSe nanorods underwent spheroidization, as indicated by the arrows in Fig. 3b. Furthermore, upon increasing the selenization temperature to 1000 °C, complete spheroidization took place, resulting in the carbon nanofibers being decorated by spherical nanocrystals, as shown in Fig. 3c. Moreover, due to Ostwald ripening, upon increasing the selenization temperature, the size of the FeSe nanocrystals increased due to crystal growth. However, even at high temperatures, the carbon nanofibers minimized crystal growth, giving a mean size of 0.9 μm for the FeSe nanospheres, as determined from the SEM images.

XPS was then employed to determine the chemical states and molecular environments of the FeSe-C composite obtained at 800 °C, as shown in Fig. 4. In the Fe 2p spectrum shown in Fig. 4a, the main peaks were observed at the characteristic FeSe binding energies of 710.2 eV (Fe 2p3/2) and 724.1 eV (Fe 2p1/2)38,39,40. In addition, in the Se 3d spectrum shown in Fig. 4b, signals were observed at binding energies of 54.5 and 55.3 eV, corresponding to Se 3d5/2 and Se 3d3/2, respectively. Signals corresponding to the oxidized-Se (Se-O) and metalloid Se (Se-Se) bonds were also observed in the XPS spectrum of Se, with the former due to the partial oxidation of metalloid Se under atmospheric conditions, and the latter likely due to the deposition of small amounts of metalloid Se within the porous carbon nanofiber during the selenization process39. Furthermore, in the C 1 s XPS spectrum (Fig. 4c), peaks corresponding to sp2-bonded carbon (C–C), epoxy and alkoxy groups (C–O), and carbonyl and carboxylic (C = O) components were observed at 284.2, 286.5, and 288.0 eV, respectively. As the peak corresponding to the C–C bond exhibited the highest intensity, and those corresponding to the C–O and C = O bonds exhibited particularly low intensities, this indicates that graphitic carbon was formed during the selenization process40.

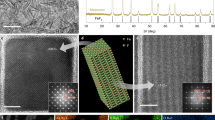

Following oxidation at 600 °C, the FeSe-C composite nanofibers formed at different selenization temperatures transformed into pure Fe2O3 nanopowders with various morphologies. The XRD patterns shown in Figure S3 confirm the complete oxidation of FeSe into Fe2O3 for all FeSe nanocrystal morphologies during the oxidation process. In addition, the SEM and TEM images shown in Fig. 5a–g reveal the formation of aggregate-free hollow Fe2O3 nanorods via the complete oxidation of the FeSe-C composite nanofibers that were obtained at a selenization temperature of 500 °C. From the SEM image, the Fe2O3 nanorods measured ~0.49 μm (mean width) by 3.40 μm (mean length), while the mean thickness of the hollow shell was determined to be 63 nm from the TEM images. The high-resolution TEM image shown in Fig. 5e shows clear lattice fringes separated by 0.25 and 0.27 nm, which correspond to the (110) and (104) crystal planes of rhombohedral hematite Fe2O3, respectively. The morphologies of the Sel.800-Oxi.600 and Sel.1000-Oxi.600 Fe2O3 powders are shown in Fig. 5h–n and o–u, respectively. Indeed, the SEM and TEM images shown in Fig. 5h–k of the Sel.800-Oxi.600 revealed two types of Fe2O3 hollow nanopowders, based on spherical and rod-like shapes, while the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders shown in Fig. 5o–r of the Sel.1000-Oxi.600 exhibited only a spherical shape. In addition, the high-resolution TEM images shown in Fig. 5i and s show clear lattice fringes separated by 0.37 and 0.27 nm, which correspond to the (012) and (104) crystal planes of Fe2O3, respectively. The FeSe crystals obtained from the FeSe-C composite nanofibers that were transformed into hollow Fe2O3 powders by the nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process are outlined in Fig. 2. Surface oxidation of the FeSe crystal resulted in the formation of an FeSe@Fe2O3 powder, which exhibited a core-shell structure. The outward diffusion of the smaller Fe cations (Fe2+ = 76 pm, Fe3+ = 65 pm) and Se anions (184 pm) occurred more rapidly than the inward diffusion of O2 gas. Thus, the formation of an SeO2 layer over the hollow powder due to the oxidation of diffused Se was eliminated by volatilization at an oxidation temperature of 600 °C. Therefore, complete diffusion of the Fe and Se components to the outside surface of the powder resulted in the formation of hollow Fe2O3 powders. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern and elemental mapping images shown in Fig. 5 therefore confirm the formation of single phase Fe2O3 powders containing no Se or C impurities.

Morphologies, SAED pattern, and elemental mapping images of the hollow-structured Fe2O3 nanopowders after oxidation at 600 °C, from the FeSe-C composite nanofibers selenized at (a–g) 500 °C, (h–n) 800 °C, and (o–u) 1000 °C: (a,h,o) SEM images, (b–d,i–k,p–r) TEM images, (e,l,s) HR-TEM images, (f,m,t) SAED patterns, and (g,n,u) elemental mapping images.

The XPS spectra and TG curve of the hollow-structured Sel.800-Oxi.600 nanopowders are shown in Fig. 6. In the Fe 2p spectrum shown in Fig. 6a, the major signals are observed at binding energies of 711.2 eV (Fe 2p3/2) and 724.2 eV (Fe 2p1/2), which are characteristic of Fe2O341,42,43,44,45. In addition, the O 1 s spectrum shown in Fig. 6b exhibits two peaks centered at 529.7 eV and 531.6 eV, which could be assigned to the oxygen atoms in the Fe2O3 lattice and to adsorbed water present on the powder surfaces45. Thus, combined with the observation of Fe 2p and O 1 s signals as discussed above, these results confirmed the formation of pure Fe2O3 phase. No components related to zero-valent Fe or Fe2+ were observed. Furthermore, the TG curve shown in Fig. 6c confirmed no distinct weight loss, with an increase in mass being observed at temperatures <600 °C, revealing the phase purity of the obtained Fe2O3 powders. Moreover, as shown in Figure S4, the BET surface areas of the hollow Sel.500-Oxi.600, Sel.800-Oxi.600, and Sel.1000-Oxi.600 nanopowders were 66, 61, and 27 m2 g−1, respectively.

The electrochemical properties for lithium-ion storage of the hollow 0D and 1D Fe2O3 nanopowders are shown in Fig. 7. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the hollow Fe2O3 powders for the first 5 cycles at a scan rate of 0.07 mV s−1 over the potential range of 0.001–3 V are shown in Figs 7a and S5. The first sharp reduction peak observed at ~0.7 V in the initial cathodic sweep corresponded to the conversion of Fe2O3 to metallic Fe and Li2O46,47,48. The two broad oxidation peaks at ~1.6 and 1.8 V in the anodic sweeps were attributed to the oxidation of Fe0 to Fe2+ and Fe2+ to Fe3+, respectively47,48. After the first cycle at a current density of 1.0 A g−1, the sharp reduction peak moved to ~0.8 V due to the conversion of Fe2O3 into ultrafine nanocrystals during the initial cycle48,49,50. In addition, Fig. 7b shows the initial charge and discharge profiles of the hollow 0D and 1D Fe2O3 nanopowders at a current density of 1 A g−1. The three samples yielded similar initial charge/discharge profiles irrespective of their morphologies. A plateau at ~0.84 V due to conversion of Fe2O3 to metallic Fe and Li2O was observed in the initial discharge process of all three samples. In addition, the initial discharge capacities of the hollow Sel.500-Oxi.600, Sel.800-Oxi.600, and Sel.1000-Oxi.600 nanopowders were 1399, 1194, and 1028 mA h g−1, respectively, their initial charge capacities were 1025, 796, and 694 mA h g−1, respectively, and their corresponding Coulombic efficiencies were 73, 67, and 68%, respectively. Indeed, the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders with 1D structure formed by oxidation of the FeSe-C composite nanofibers obtained at a selenization temperature of 500 °C exhibited the highest initial discharge capacity and Coulombic efficiency of the three samples. However, as shown in Fig. 7c, the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders exhibited excellent cycling performances at a current density of 1 A g−1 irrespective of morphology. Furthermore, the discharge capacities for the 1000th cycle of the hollow Sel.500-Oxi.600, Sel.800-Oxi.600, and Sel.1000-Oxi.600 nanopowders were 932, 767, and 544 mA h g−1, respectively, and their capacity retentions measured from the second cycle were 88, 92, and 78%, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7d, all three hollow Fe2O3 powders also exhibited excellent rate performances. The final discharge capacities of the hollow Sel.500-Oxi.600 powders at current densities of 0.5, 1.5, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, and 10.0 A g−1 were 1041, 926, 844, 785, 747, and 700 mA h g−1, respectively. Indeed, all three samples prepared at different selenization temperatures exhibited good capacity recovery when the current density returned to 0.5 A g−1, even after cycling at high current densities. As shown in Figure S6, the rate capability of the hollow Sel.500-Oxi.600 powders at extremely high current densities was also analyzed. The hollow 1D Fe2O3 nanopowders had final discharge capacities of 1083, 895, 801, 691, 613, 547, and 500 mA h g−1 at current densities of 0.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0 and 50.0 A g−1, respectively. In general, electrochemical properties of anode materials in LIBs are strongly affected by many factors, including their morphologies, crystal structures, crystallite sizes, and BET surface areas, etcetera. Therefore, the characteristics of the samples are summarized in Table S1. The rod-like Sel.500-Oxi.600 nanopowders showed the smallest crystallite and particle size, and the largest BET surface area among the samples. These features provide short transport lengths for Li ions and electrons, increased contact areas between the electrolyte and electrode for Li ions insertion–desertion, and efficient electron transport along the interconnected nanoparticle network, hence enhancing electrochemical properties. Consequently, Sel.500-Oxi.600 nanopowders with the smaller crystallite and particle size, and larger BET surface area exhibited enhaced the initial discharge capacity and cycling performance.

The excellent Li-ion storage performances of the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders formed from the FeSe-C composite nanofibers were confirmed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy(EIS) measurements before and after 1 and 200 cycles. The Nyquist plots (Fig. 8) exhibit compressed semicircles in the medium-frequency range, which describe the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) of the electrode51,52,53. In addition, the hollow Sel.1000-Oxi.600 nanopowders exhibited a slightly higher charge transfer resistance than the other two samples. However, the three samples had similar charge transfer resistances after 1 and 200 cycles, with the low charge-transfer resistances of the three samples observed following the 1st cycle (due to the formation of ultrafine nanocrystals) increasing slightly after 200 cycles. This is likely due to the partial structural destruction of the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders during repeated lithium insertion/desertion, which increases the charge transfer resistances for all morphologies. Finally, as shown in Fig. 9, the overall morphologies of the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders were maintained even after 200 cycles. The electrochemical properties of the hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders prepared from the FeSe-C composite nanofibers at different selenization temperatures were compared with those of hollow Fe2O3 materials reported in the literatures, and the results were summarized in Table S2. The hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders prepared in this study showed superior lithium-ion storage performances compared to those of the other Fe2O3 materials prepared from various processes even at a high current density of 1.0 A g−1 during 1000 cycles.

Conclusions

A new process for the preparation of aggregate-free iron oxide nanopowders with spherical (0D) and non-spherical (1D) hollow nanostructures was investigated and developed. Ostwald ripening and the nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process were successfully applied to the electrospinning process to synthesize the desired hollow nanopowders. The FeSe-C composite nanofibers formed via Ostwald ripening were transformed into hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders with either 0D or 1D nanostructures via a one-pot oxidation process through nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion, with selenization temperature of 500, 800, and 1000 °C being investigated. The prepared hollow Fe2O3 nanopowders exhibited excellent lithium-ion storage capabilities. We propose that the three-step process developed in this study can be efficiently applied in the preparation of other hollow metal oxide nanopowders with nanostructures of various dimensions (e.g., 0–3D) for applications such as lithium-ion batteries.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation

Spherical (0D) and non-spherical (1D) Fe2O3 hollow nanostructures were prepared in three steps, namely the formation of electrospun precursor nanofibers and two subsequent post-treatment steps. Initially, Fe(acac)3-polyacrylonitrile (PAN) [Fe(acac)3–PAN] composite nanofibers were prepared as the precursor nanofibers via electrospinning. The electrospinning precursor solution was prepared by dissolving Fe(acac)3 (6.0 g, STREM Chemicals, 99%) and PAN (4.0 g, Sigma-Aldrich, Mw: 150,000) in N,N-dimethylformamide (60 mL, DMF, Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) with vigorous stirring overnight. The prepared solution was loaded into a plastic syringe equipped with a 25-gauge stainless steel nozzle at a flow rate of 2 mL h−1. The solution was subsequently ejected and electrospun onto a drum collector covered with aluminum foil. During the electrospinning process, the distance between the tip and the collector was maintained at 20 cm, while the rotation of the drum was maintained at 100 rpm. The applied voltage between the collector and the syringe tip was 25 kV. The resulting Fe(acac)3–PAN composite nanofibers were stabilized at 120 °C under air for 5 h. Subsequently, the initial post-treatment step to achieve selenization of the electrospun nanofibers was conducted at 500, 800, or 1000 °C for 6 h under H2Se gas. H2Se was generated from commercial Se metal powder and H2 gas. In the selenization process, the Fe(acac)3–PAN composite nanofibers and Se metal powder were loaded into a covered alumina boat and placed in a quartz tube reactor. Selenization resulted in the formation of FeSe-carbon composite nanofibers. The subsequent oxidation process was conducted under air at 600 °C for 3 h. For simplicity, the hollow Fe2O3 powders obtained from the FeSe-C composite nanofibers prepared at 500, 800, and 1000 °C are referred to as “Sel.500-Oxi.600,” “Sel.800-Oxi.600,” and “Sel.1000-Oxi.600,” respectively.

Characterization

The hollow Fe2O3 powder microstructures were observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, S-4800, Hitachi) and field emission transmission electron microscopy (FE-TEM, JEM-2100F, JEOL). In addition, their crystal phases were evaluated by X-ray diffractometry (XRD, X’Pert PRO MPD, PANalytical) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at the Korea Basic Science Institute (Daegu). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific K-AlphaTM) with a focused monochromatic Al Kα beam at 12 kV and 20 mA was used to analyze the composition of the specimens. The surface areas of the nanofibers were measured using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, using N2 as the adsorbate gas. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a Pyris 1 TGA (Perkin Elmer) at 25–650 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under air.

Electrochemical measurements

The electrochemical properties of the hollow Fe2O3 powders were analyzed by constructing a 2032-type coin cell. The anode was prepared by mixing the active material, carbon black, and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) in a weight ratio of 7:2:1. Li metal and microporous polypropylene film were used as the counter electrode and the separator, respectively. The electrolyte was composed of 1 M LiPF6 dissolved in a mixture of fluoroethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (FEC/DMC; 1:1 v/v). The discharge/charge characteristics of the samples were investigated by cycling over a potential range of 0.001–3 V at various current densities. Cyclic voltammograms were measured at a scan rate of 0.07 mV s−1. The Fe2O3-containing negative electrode measured 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm, and the mass loading of the active materials was kept approximately 1.5 mg cm−2 in every electrochemical test. Electrochemical impedance spectra were obtained by performing alternating current electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS, ZIVE SP1) over a frequency range of 0.01 Hz to 100 kHz.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Cho, J. S. et al. Preparation of Hollow Fe2O3 Nanorods and Nanospheres by Nanoscale Kirkendall Diffusion, and Their Electrochemical Properties for Use in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 6, 38933; doi: 10.1038/srep38933 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Wu, R. et al. Porous spinel ZnxCo3–xO4 hollow polyhedra templated for high-rate lithium-ion batteries. ACS Nano 8, 6297–6303 (2014).

Yu, L., Xia, B. Y., Wang, X. & Lou, X. W. General formation of M–MoS3 (M=Co, Ni) hollow structures with enhanced electrocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 28, 92–97 (2016).

Ji, L. et al. Controlling SEI formation on SnSb‐porous carbon nanofibers for improved Na ion storage. Adv. Mater. 26, 2901–2908 (2014).

Niu, C. et al. VO2 nanowires assembled into hollow microspheres for high-rate and long-life lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 2873–2878 (2014).

Liu, J. et al. Three-dimensionally interconnected nickel–antimony intermetallic hollow nanospheres as anode material for high-rate sodium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 16, 389–398 (2015).

Yang, T. et al. A sustainable route from biomass byproduct okara to high content nitrogen‐doped carbon sheets for efficient sodium ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 28, 539–545 (2016).

Wang, X., Chen, Y., Schmidt, O. G. & Yan, C. Engineered nanomembranes for smart energy storage devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 1308–1330 (2016).

Cho, J. S. & Kang, Y. C. Nanofibers comprising yolk–shell Sn@void@SnO/SnO2 and hollow SnO/SnO2 and SnO2 nanospheres via the Kirkendall diffusion effect and their electrochemical properties. Small 11, 4673–4681 (2015).

Zhang, K., Zhao, Q., Tao, Z. & Chen, J. Composite of sulfur impregnated in porous hollow carbon spheres as the cathode of Li-S batteries with high performance. Nano Res. 6, 38–46 (2013).

Cho, J. S., Won, J. M., Lee, J. K. & Kang, Y. C. Design and synthesis of multiroom-structured metal compounds–carbon hybrid microspheres as anode materials for rechargeable batteries. Nano Energy 26, 466–478 (2016).

Shim, J. O. et al. Highly active and stable Pt-loaded Ce0.75Zr0.25O2 yolk–shell catalyst for water–gas shift reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 17239–17244 (2016).

Patel, S. K. S., Choi, S. H., Kang, Y. C. & Lee, J. K. Large-scale aerosol-assisted synthesis of biofriendly Fe2O3 yolk–shell particles: a promising support for enzyme immobilization. Nanoscale 8, 6728–6738 (2016).

Xie, Q. et al. Template-free synthesis of amorphous double-shelled zinc–cobalt citrate hollow microspheres and their transformation to crystalline ZnCo2O4 microspheres. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 5, 5508–5517 (2013).

Lai, X. et al. General synthesis and gas‐sensing properties of multiple‐shell metal oxide hollow microspheres. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 123, 2790–2793 (2011).

Zhao, Y. & Jiang, L. Hollow micro/nanomaterials with multilevel interior structures. Adv. Mater. 21, 3621–3638 (2009).

Zhu, Y., Hu, D., Wan, M. X., Jiang, L. & Wei, Y. Conducting and superhydrophobic rambutan‐like hollow spheres of polyaniline. Adv. Mater. 19, 2092–2096 (2007).

Wang, Z. & Lou, X. W. TiO2 nanocages: fast synthesis, interior functionalization and improved lithium storage properties. Adv. Mater. 24, 4124–4129 (2012).

Hyodo, T., Sasahara, K., Shimizu, Y. & Egashira, M. Preparation of macroporous SnO2 films using PMMA microspheres and their sensing properties to NOx and H2 . Sens. Act. B 106, 580–590 (2005).

Meyer, U., Larsson, A., Hentze, H. P. & Caruso, R. A. Templating of porous polymeric beads to form porous silica and titania spheres. Adv. Mater. 14, 1768–1772 (2002).

Johnson, S. A., Ollivier, P. J. & Mallouk, T. E. Ordered mesoporous polymers of tunable pore size from colloidal silica templates. Science 283, 963–965 (1999).

Railsback, J. G., Johnston-Peck, A. C., Wang, J. & Tracy, J. B. Size-dependent nanoscale Kirkendall effect during the oxidation of nickel nanoparticles. ACS Nano 4, 1913–1920 (2010).

Lou, X. W., Wang, Y., Yuan, C., Lee, J. Y. & Archer, L. A. Template‐free synthesis of SnO2 hollow nanostructures with high lithium storage capacity. Adv. Mater. 18, 2325–2329 (2006).

Zeng, H. C. Ostwald ripening: A synthetic approach for hollow nanomaterials. Curr. Nanosci. 3, 177–181 (2007).

Pan, J. H., Zhang, X., Du, A. J., Sun, D. D. & Leckie, J. O. Self-etching reconstruction of hierarchically mesoporous F-TiO2 hollow microspherical photocatalyst for concurrent membrane water purifications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 11256–11257 (2008).

Cho, J. S., Won, J. M., Lee, J. H. & Kang, Y. C. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of spherical and hollow-structured NiO aggregates created by combining the Kirkendall effect and Ostwald ripening. Nanoscale 7, 19620–19626 (2015).

Aldinger, F. Controlled porosity by an extreme Kirkendall effect. Acta Metall. Mater. 22, 923–928 (1974).

Fan, H. J. et al. Influence of surface diffusion on the formation of hollow nanostructures induced by the Kirkendall effect: the basic concept. Nano Lett. 7, 993–997 (2007).

Yin, Y. et al. Formation of hollow nanocrystals through the nanoscale Kirkendall effect. Science 304, 711–714 (2004).

Cho, J. S., Hong, Y. J. & Kang, Y. C. Design and synthesis of bubble-nanorod-structured Fe2O3–carbon nanofibers as advanced anode material for Li-ion batteries. ACS Nano 9, 4026–4035 (2015).

Wang, R., Xu, C., Sun, J. & Gao, L. Three-dimensional Fe2O3 nanocubes/nitrogen-doped graphene aerogels: Nucleation mechanism and lithium storage properties. Sci. Rep. 4, 7171–7177 (2014).

Park, G. D., Cho, J. S., Lee, J. K. & Kang, Y. C. Na-ion storage performances of FeSex and Fe2O3 hollow nanoparticles-decorated reduced graphene oxide balls prepared by nanoscale Kirkendall diffusion process. Sci. Rep. 6, 22432–2441 (2016).

Yun, S., Lee, Y. C. & Park, H. S. Phase-controlled iron oxide nanobox deposited on hierarchically structured graphene networks for lithium ion storage and photocatalysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 19959–19967 (2016).

Chen, M. et al. The effect of crystal face of Fe2O3 on the electrochemical performance for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 6, 29381–29389 (2016).

Jeong, J. M. et al. Hierarchical hollow spheres of Fe2O3@ polyaniline for lithium ion battery anodes. Adv. Mater. 25, 6250–6255 (2013).

Gu, Y. et al. Construction of point-line-plane (0-1-2 dimensional) Fe2O3-SnO2/graphene hybrids as the anodes with excellent lithium storage capability. Nano Res. 1–13 (2016).

Chen, J., Xu, L., Li, W. & Gou, X. L. α‐Fe2O3 nanotubes in gas sensor and lithium‐ion battery applications. Adv. Mater. 17, 582–586 (2005).

Chen, J. S., Zhu, T., Yang, X. H., Yang, H. G. & Lou, X. W. Top-down fabrication of α-Fe2O3 single-crystal nanodiscs and microparticles with tunable porosity for largely improved lithium storage properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 13162–13164 (2010).

Sobhani, A. & Salavati-Niasari, M. Synthesis and characterization of FeSe2 nanoparticles and FeSe2/FeO (OH) nanocomposites by hydrothermal method. J. Alloys Compd. 625, 26–33 (2015).

Zheng, Q., Cheng, X. & Li, H. Microwave synthesis of high activity FeSe2/C catalyst toward oxygen reduction reaction. Catalysts 5, 1079–1091 (2015).

Cho, J. S., Lee, J. K. & Kang, Y. C. Graphitic carbon-coated FeSe2 hollow nanosphere-decorated reduced graphene oxide hybrid nanofibers as an efficient anode material for sodium ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 6, 23699 (2016).

Huang, S. et al. 3D hierarchical FeSe2 microspheres: Controlled synthesis and applications in dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano Energy, 15, 205–215 (2015).

Xia, H. et al. Hierarchical TiO2-B nanowire@α-Fe2O3 nanothorn core-branch arrays as superior electrodes for lithium-ion microbatteries. Nano Res. 7, 1797–1808 (2014).

Beidaghi, M. & Wang, C. Micro‐supercapacitors based on interdigital electrodes of reduced graphene oxide and carbon nanotube composites with ultrahigh power handling performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 4501–4510 (2012).

Hu, X., Yu, J. C., Gong, J., Li, Q. & Li, G. α‐Fe2O3 nanorings prepared by a microwave‐assisted hydrothermal process and their sensing properties. Adv. Mater. 19, 2324–2329 (2007).

Evangelisti, C. et al. Chemoselective hydrogenation of halonitroaromatics over γ-Fe2O3-supported platinum nanoparticles: The role of the support on their catalytic activity and selectivity. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 366, 288–293 (2013).

Reddy, M. V. et al. α‐Fe2O3 nanoflakes as an anode material for Li‐ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 2792–2799 (2007).

Qu, J. et al. Layer structured α-Fe2O3 nanodisk/reduced graphene oxide composites as high-performance anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 3932–3936 (2013).

Chaudhari, S. & Srinivasan, M. 1D hollow α-Fe2O3 electrospun nanofibers as high performance anode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 23049–23056 (2012).

Sun, Y., Hu, X., Luo, W., Xia, F. & Huang, Y. Reconstruction of conformal nanoscale MnO on graphene as a high‐capacity and long‐life anode material for lithium ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 2436–2444 (2013).

Rahman, M. M., Wang, J. Z., Hassan, M. F., Wexler, D. & Liu, H. K. Amorphous carbon coated high grain boundary density dual phase Li4Ti5O12‐TiO2: A nanocomposite anode material for Li‐ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 1, 212–220 (2011).

Xu, Y., Zhu, Y., Liu, Y. & Wang, C. Electrochemical performance of porous carbon/tin composite anodes for sodium‐ion and lithium‐ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 128–133 (2013).

Li, N. et al. Battery performance and photocatalytic activity of mesoporous anatase TiO2 nanospheres/graphene composites by template‐free self‐assembly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 1717–1722 (2011).

Guo, B. et al. Soft‐templated mesoporous carbon‐carbon nanotube composites for high performance lithium‐ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 23, 4661–4666 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (NRF-2015R1A2A1A15056049). This work was supported by the Energy Efficiency & Resources Core Technology Program of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), granted financial resource from the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy, Republic of Korea (20153030091450).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.C. and J.S.P are co-first authors with equal contribution to this work. J.S.C. and Y.C.K. devised the concept, designed the experiment, and wrote the manuscript. J.S.C. and J.S.P performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Y.C.K. supervised the project. J.S.C. and Y.C.K. discussed the results and contributed in this manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, J., Park, JS. & Kang, Y. Preparation of Hollow Fe2O3 Nanorods and Nanospheres by Nanoscale Kirkendall Diffusion, and Their Electrochemical Properties for Use in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci Rep 6, 38933 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38933

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38933

This article is cited by

-

Iron cobalt selenide counter electrode for application in dye-sensitized solar cell: synthesis parameter, structural, electrochemical, and efficiency studies

Ionics (2024)

-

Hierarchical Fe2O3 hexagonal nanoplatelets anchored on SnO2 nanofibers for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitor device

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Synthesis of Hollow Nanostructures Based on Iron Oxides and Their Applications in Lithium-Ion Batteries

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

-

Facile construction of honeycomb-shaped porous carbon electrode materials using recyclable sodium chloride template for efficient lithium storage

Science China Technological Sciences (2020)

-

Double-walled iron oxide nanotubes via selective chemical etching and Kirkendall process

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.