Abstract

Inducing α-helicity through side-chain cross-linking is a strategy that has been pursued to improve peptide conformational rigidity and bio-availability. Here we describe the preparation of small peptides tethered to chiral sulfoxide-containing macrocyclic rings. Furthermore, a study of structure-activity relationships (SARs) disclosed properties with respect to ring size, sulfur position, oxidation state, and stereochemistry that show a propensity to induce α-helicity. Supporting data include circular dichroism spectroscopy (CD), NMR spectroscopy, and a single crystal X-ray structure for one such stabilized peptide. Finally, theoretical studies are presented to elucidate the effect of chiral sulfoxides in inducing backbone α-helicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to recent statistical analysis of the Protein Data Bank (PDB), roughly 60 percent of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) involve α-helices at the interface, and most of the α-helices consist of 15 amino acids or less1,2. These PPIs play a critical role in numerous biological processes and represent a rich array of potential therapeutic targets3,4,5. Despite small molecule’s therapeutic potential6,7,8,9, development of small molecule PPI ligands is still formidable due to the shallow, large, and even disconnected PPI surfaces10; meanwhile, large proteins are often unsuitable for intracellular PPIs due to poor cell permeability. Consequently, intracellular PPIs were once considered “undruggable”.

Short peptides are generally less structurally defined in aqueous solutions as water molecules can disrupt the intramolecular hydrogen bonding of the peptide backbone. When constrained into rigid α-helical conformations, short peptides can mimic protein binding surfaces and exhibit greater resistance against metabolizing enzymes11. Developing methodologies to predictably induce α-helices in short peptides is therefore of considerable interest for peptide-based drug development12,13,14,15,16. Over the past several decades, various approaches, spanning non-covalent and covalent strategies, to reinforcing the bioactive helical conformation were developed17. Various non-covalent strategies have been used to stabilize peptide backbone toward the a-helical conformation, including helix-nucleating templates18,19,20,21 and introducing α, α-disubstituted amino acid, such as aminoisobutyric acid22,23. While for covalent strategies, a common approach for inducing and stabilizing fixed secondary structure in peptides is by tethering two side chains on the same face of the helix via different cross-links. These so-called stapled peptides have been extensively studied in recent years and have been the subjects of numerous reviews24,25,26. In general, these stapled peptides have different cross-links, such as aryl, alkenyl, disulphide, “click” triazole, amide, and thioether connectors16,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Besides, while we know that peptides are composed of chiral L-amino acids, the effect of stereocenters within the cross-links in peptide secondary structure has not been extensively studied.

Results and Discussion

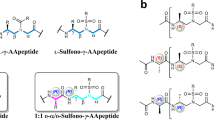

Recently, our group reported a chiral carbon-centered tether that controlled the secondary structure of peptides via its absolute configuration35. Meanwhile, Moore et al. reported that a chiral center on a stapled peptide affected a peptide’s secondary structure36 (Fig. 1). Notably, the preference of different chiral center positions of Moore et al.’s system and ours may be caused by the missing of α-methyl groups on the linking amino acid residues in our system and the bonding pattern differences between olefin and single bonded thiolether tethers. In the present study, we set out to evaluate short peptides with chiral sulfoxide-containing cross-links and examined the structure-activity relationships (SARs) that induced α-helicity within these molecules. Comparing with the thiolether tethered peptides, the oxidized peptides showed better solubility in aqueous solution. Notably, experimental and simulation results for the less hindered sulfoxide model elucidate the importance of a precisely positioned chiral center for inducing backbone peptides’ helicity. We discovered that in addition to cross-link length and the position of the sulfoxide moiety, the absolute configuration of the sulfoxide appears to be essential for inducing α-helicity. Importantly, this on-tether chiral-centered-induced α-helicity appears to afford general flexibility in amino acid content for the peptides that were evaluated. The measured enhancement in α-helicity induction is comparable to the highest reported values by CD spectrum, but have a relatively higher fray at C-terminal compared with the amide cross-linked peptides Ac-c(1,5)-[KAAAD]-NH2 by 2D NMR study34,37.

The initial construct of the peptides prepared for this investigation involved pentapeptides of similar composition to those that have appeared in relevant literature34. In this study, L-Cysteine and L-amino acids Xn (as shown in SI) with an aliphatic alkenyl modification were chosen as coupling partners38. Single turn peptides Ac-c(1,5)-[CAAAXn]-NH2 (1-4) and Ac-c(1,5)-[XnAAAC]-NH2 (5-8) were picked as simplified model peptides to eliminate possibility of any sequence perturbations (Fig. 2a). Peptides 1-8 exhibited only minimal helical character based on circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy measurements with 10 mM PBS (pH = 7.4) buffer as solvent (SI Fig. 1a)37. Peptides 5-8 (with cysteine at the C terminus) showed slightly more α-helical content than peptides 1-4 (with cysteine at the N terminus) in PBS and TFE buffer, with peptide 7 exhibiting the highest degree of α-helicity in TFE buffer (SI Fig. 1b). Oxidation of these peptides produced a mixture of their corresponding sulfoxide diastereomers, indicated as peptides 9-12 and peptides 13-16 (Fig. 2b). For peptides 9, 11 and 12, the diastereomers were difficult to separate by HPLC, and CD spectroscopy measurements of the mixtures suggested a random coil structure. The diastereomers of 10 were separable and exhibited only minimal α-helicity (SI Fig. 2a). The diastereomers of 13-16 were easily separable, suggesting they adopted higher conformational differences in solution. CD spectroscopy measurements of (R)-15B (the diastereomer with a longer retention time) consistently show a high degree of α-helicity, while the CD spectrum for (S)-15A indicates a random coil (Fig. 2b; see also SI Fig. 2b for CD spectra of peptides 13A-16A). Importantly, the CD spectra for peptides 13B-16B (SI Fig. 2c) suggest that X5 provided the optimal linker length for inducing α-helicity. We also evaluated the influence of chiral sulfoxide on CD spectrum by using (S)-(-)-2-Methyl-2-propanesulfinamide(S-BSN) and its enantiomer R-BSN, which have distinct t-butyl and amino group substitutions on the chiral center. By subtracting R-BSN and S-BSN absorption on (S)-15A and (R)-15B’s CD spectrum, their α-helical content is somewhat enhanced (base on [θ]215) while with a slightly shifted minima ([θ]203/[θ]217; 1.0:0.73) (SI Fig. 3). Overall, chiral sulfoxide center itself has limited influence on the peptides’ CD sepctra. Furthermore, these data clearly indicate that the C terminus is the optimal position for the cysteine and that shifting the sulfoxide moiety one atom towards the cross-linker center diminishes α-helicity (Ac-c(1,5)-[X4AAAC*(O)]-NH2 peptide 17; C*: homocysteine, See SI Fig. 4a for CD spectroscopies of peptide 17). 1H NMR and NOE measurements were taken for (S)-15A, (R)-15B and (R)-19B) (SI Fig. 5, SI Fig. 6). A number of characteristic spectral features of a high degree helical behavior were observed. First of all, conspicuously small 3JNH-Hα constants (<6 Hz) were observed for all amide resonances except Cys5 for (R)-15B (SI Table 1). For (R)-19B, the side chain difference on residue 3 resulted in a slightly larger 3JNH-Hα (7.2 Hz) (SI Table 1). The second NMR evidence for helicity was smaller Δδ/T (<4 ppb/K) for Ala2, Ala4, Cys5 and one C-terminal NH for (R)-15B, which suggested propensity of forming intra-molecular hydrogen bonds (SI Table 2). Long range ROEs (NH(i) – Hα(i-3)) were also observed for (R)-15B. However, due to the signal overlapping of α protons, it’s hard to confirm the key ROEs from NH(i) - Hα(i-4). Finally, from a practical standpoint, the chiral sulfoxide-containing cross-link approach avoids the need for quaternary carbon centers at the amino acid alpha position. This represents a potential advantage over methodologies requiring such a carbon center in order for olefin metathesis chemistry to proceed29,32,39. Notably, the addition of an α-methyl group to X5 of (R)-15B to get its derivative peptide (R)-18B (Ac-c(1,5)-[X5*AAAC(O)]-NH2, X5*: α methylated X5) greatly diminishes α-helicity (see SI Fig. 4b for CD spectroscopy of (S)-18A and (R)-18B). Sulfoxide could racemize under 6 M HClO440. Under the biorelevant acidic or basic conditions tested, there was no detectable sulfoxide racemization.

Subsequently, the generality of these observations was examined. A series of single turn α-helical peptides with varying sequences and containing the on-tether chiral center as indicated above were synthesized. These peptides were separated by HPLC to give peptides (R)-19B-24B, and their α-helicities were tested via CD spectroscopy (Fig. 3a). As shown in Table 1, all of these peptides exhibited a high degree of α-helicity, including (R)-20B, which contained a flexible glycine. When sulfoxide-containing peptides 15 and 19 were further oxidized to their corresponding sulfones (25 and 26), significantly diminished α-helicity was observed (Fig. 3b). This finding suggests that the sulfoxide’s chirality plays a critical role in controlling the peptide backbone’s α-helicity.Additionally, temperature-dependent CD spectroscopy measurements on (R)- diastereomer 19B indicate temperature tolerance, and at 65 °C, (R)-19B retained 75% of the helicity that it showed at 30 °C (Fig. 3c,d).

(a) CD spectra of (R)-diastereomer 19B-24B. (b) CD spectra of sulfone-containing peptides 25 and 26 show minimal helix contents. (c) CD spectroscopy was performed for (R)-19B at increasing temperatures. Its helicity decreased slightly as temperature increased (d) At 65 °C, (R)-19B retained 75% of the helicity that it showed at 30 °C. CD spectroscopy was performed in 10 mM PBS (pH = 7.4) buffer at 25 °C.

Finally, X-Ray crystallography of (R)-19B confirmed the aforementioned CD and NMR data and unambiguously established the absolute (R) configuration for the sulfoxide (S=O) chiral center. Furthermore, the crystal structure clearly indicates that there is no hydrogen bond between the sulfoxide oxygen and any of the peptide backbone hydrogen bond donors, and that the intramolecular hydrogen-bonding pattern agrees with the proposed α-helix model (Fig. 4a). The small C-S-C bond angle at the sulfoxide (S=O) center measures 96°, which helps to constrain the peptide backbone (SI Fig. 9). By contrast, the (S)-19A could not be crystallized. In the crystal structure of (R)-19B, two nearly identical structures co-exist in one crystal lattice. In addition, the presence of water molecules within the crystal lattice suggests the peptide retains its helical conformation in solution. The three residues in the middle are very close to being an ideal α-helix with average rise-per-residue of 1.47 Å and 3.68 residues per turn, and the backbone dihedral angles (φ, ψ) of residues X5-1 to Ala-4 were very close to regular α-helical dihedral angles (SI Table 3). The dihedral angles of the C-terminal residue Cys-5 (φ = −109°, ψ = −8°) deviate significantly from those of a perfectly regular α-helix41 (φ = −65°, ψ = −40°). This observation is very similar to that seen in crystal structures of hydrogen bond surrogate (HBS)-stabilized α-helixes42 and protein crystal structures41.

Crystal structure of (R)-19B and calculated structures of (S)-15A, (R)-15B.

(a) X-ray crystal structure of (R)-19B with thermal ellipsoids shown at the 50% probability level with three α-helical hydrogen bonds. (b) Conformers of (R)-diastereomer 15B (R1, R2) and (S)-diastereomer 15A (S1, S2, S3, S4) with increased stability, calculated with density functional theory at PBE1PBE/6-31 + G** level. Relative free energies are given below each structure. (c) Conformations sampled in REMD simulations of (S)-19A and (R)-19B. The x-axis is the backbone RMSD of the conformations, with respect to the X-ray structure of (R)-19B. The y-axis is the radius of gyration of the conformations. The clusters are labelled as R1′(19B), R2′(19B) and S1′-S3′(19A), similar to structures R1(15B), R2(15B), and S1-S3(15A) in (b), see SI Fig. 8 for the structures of R1′(19B), R2′(19B) and S1′-S3′(19A).

Further theoretical studies were carried out using (S)-15A and (R)-15B as models. Their possible conformations were researched using HyperChem software43. Low energy conformations were further optimized with the density functional theory (DFT) method of PBE1PBE44, and the SMD model45 was used to estimate the solvent effect of water. Free energies were obtained via vibrational frequency calculations. For the (R)-15B, the most stable conformer was found to be α-helical as indicated in structure R1(15B) (Fig. 4b). This is very similar to what was observed in the crystal structure of (R)-19B. R2(15B), with a 310-helix (two successive β-turns) was found to be less stable than R1 by about 1.2 kcal/mol. However, the two most stable conformers (S1(15A), S2(15A)) of the (S)-diastereomer (15A) are not α-helical, instead they contain a short 310-helical structure and two extended residues, which consistent with the NMR result of (S)-15A. A distorted α-helical structure S3(15A) is 1.6 kcal/mol less stable than S1(15 A). As shown in Fig. 4c, these results are in good agreement with the replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD)46 simulation (with AMBER99SB/GB47,48 force field) results for (S)-19A and (R)-19B, where R1′(19B) and S1′(19A), which correspond to R1(15B) and S1(15A), respectively, are dominant.

A question remains: why is the helical structure of the (S)-diastereomer disfavored? In the α-helical structure R1(15B), the χ1 (N-C-C-S) dihedral angle is approximately −66°. The S=O bond points away from the peptide α-helix so that there is no steric hindrance. We optimized a structure S4(15A) that is nearly identical to R1(15B) except that the sulfoxide center is in (S) configuration. S4(15A) is calculated to be less stable than S1(15A) by about 3.9 kcal/mol. This is due to the steric interactions between the S=O oxygen atom and the peptide as indicated by the increase in χ1 to −81°. One way to avoid the steric interactions is to rotate the χ1 dihedral angle so that the S=O is away from the peptide. This is the case in S1(15A) and S2(15A), where χ1 changes to around −167°. However, this change renders the linker too short to maintain the α-helix. As a result, the N-terminus is forced away from the α-helical structure and only a short 310-helix remains in S1(15A) and S2(15A). Another way to avoid the steric interactions in S4(15A) is to distort the α-helix, as is the case in S3(15A). However, this causes significant destabilization.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a precisely-positioned sulfoxide moiety in a peptide “staple”, with (R)-stereochemical configuration, is capable of inducing a single turn peptide into α-helical structure in aqueous solution. CD spectra and corroborating NMR experiments support these observations. By contrast, the corresponding peptides containing thioethers and sulfones exhibited minimal enhancement of α-helicity. α-helicity critically depends on the cross-link (staple) length, for which seven atoms are optimal. DFT and REMD calculations also show that peptides with an (R)-sulfoxide cross-link favor α-helical conformation, while the (S)-containing peptides do not. This stabilization strategy exhibits excellent peptide sequence tolerance. Finally, this investigation into the ability of (R)-sulfoxides to induce α-helical conformation in peptides informs research regarding the chiral modification of cross-links in staple peptides.

Methods

Preparation of thiolether, sulfoxide and sulfone cross-linking peptides

Thiolether cross linking peptide 1 and 2 was synthesized following general procedure A in supporting information. First H2N-Ala-Ala-Ala-Xn-resin (Rink amide MBHA, n = 3, 4) was synthesized using Fmoc chemistry. Then thiol-addition of N-Acetyl-L-cysteine to the terminal olefin of resin bond Xn was conducted by DMPA catalyst and UV irradiation. The result peptide H2N-Ala-Ala-Ala-Xn(N-Acetyl-L-cysteine)-NH2 was cleaved by cleavage cocktail (TFA/TIS/EDT/H2O 94/1/2.5/2.5) from resin, and then macro-cyclized in solution by amide bond formation. Peptides 3, 4, 7, 8 and the thiolether counterpart for peptide 17-24 was synthesized following our former study35, and detailed procedure was presented in the supporting information (general procedure B). Peptide 5 and 6 was synthesized with similar procedure as 1 and 2, except that CTC resin and L-Cysteinamide monohydrochloride was used instead of Rink amide AM resin and N-Acetyl-L-cysteine.

The sulfoxide cross linking peptide was produced by oxidation of their thiolether counterpart. Oxidation reaction was conducted in 5% H2O2 (1 mL per 2.5 mg thiolether peptide) for 3 h at room temperature (1% H2O2 and ice bath for 23 and 24).

Sulfone cross linking peptide 25 and 26 was synthesized by oxidizing sulfoxide peptide 15 and 19 with 1.5% H2O2 in acetic acid (1 mL per 3 mg peptide) for 8 h at room temperature.

Characterization of Peptides by CD spectroscopy

Stapled peptides were dissolved in aqueous 10 mM potassium phosphate solution (pH 7.4) or 50% TFE buffer to concentrations of 50–800 μM. CD spectra were obtained on a Chirascan Circular Dichroism Spectrometer at 25 °C using the following standard measurement parameters: wavelength, 190–250 nm; step resolution, 0.5 nm; speed, 20 nm/sec; accumulations, 10; response, 1 sec; bandwidth, 1 nm; path 3 length, 0.1 cm. Every sample was scanned twice and the final CD spectrum was smoothed to reduce noise. The α-helical content of each peptide was calculated by dividing the mean residue ellipticity [θ]222obs by the reported [θ]222obs for a model α-helical pentapeptide.

Crystallization and Data Collection

Peptide 19B was dissolved in 50% CH3OH with 10 mg/mL and crystallized at 25 °C using sitting drop vapor diffusion method against reservoir solution of 90% CH3OH. Crystals appeared, attained full size within 20 days, and then started to decay after four weeks. Crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and cryo-protected by 30% Glycerol in mother liquor. The crystals were screened and collected at 100 K by in-house X-ray diffraction system equipped with high-intensity sealed Copper tube X-ray generator (Rigaku® MicroMax-002+), an AFC11 goniometer, a Saturn 944+ CCD detector (Rigaku®) and an Oxford Cryo-system.

NMR data acquisition and processing

Peptides were prepared in 1 × PBS buffer containing 10% D2O or PBS/TFE (50/50 v/v) within a concentration range of 1–5 mM. 0.5 mM sodium (3-trimethylsilyl)-2, 2, 3, 3-tetradeuterio-propionate (TSP) was added for 1 H chemical shift reference. NMR data was recorded on Bruker AVANCE III 500 MHz spectrometer. 1D spectra were acquired using excitation sculpting for water suppression. 32 K data points were collected with 8000 Hz sweep width, 3 s repetition time and 16 scans. The temperature ranged between 283 K and 303 K for temperature coefficient measurement. Standard 2D NMR methods were used to make assignments of proton signals. TOCSY (mixing time 80 ms) and ROESY(relaxation delay 2.0 s, mixing time 200 ms) experiments were recorded at 283 K in phase-sensitive mode with spectral width of 5000 Hz, 2048 points on F2 and 256 increments on F1. Solvent suppression was achieved using water gate W5 method. NMR data were processed using Topspin 3.0. We used the temperature coefficient as a tool to characterize the propensity of exchangeable protons to form IMHBs. The protection of IMHBs decreased the temperature dependence of the chemical shift of the exchangeable protons. This resulted in a smaller value of Δδ/T compared to the non-IMHB donors. In general, the cutoff value for Δδ/T for IMHBs was solvent dependent. In aqueous solution, values of Δδ/T less negative than −4.0 ppb/K usually indicated hydrogen bonding. Peptide characterization 1HNMR was performed in DMSO-d6 or in H2O/D2O 9:1.

Quantum Mechanical Calculations

To generate initial structures for further QM calculations, conformational searches were carried out with Amber and Charmm force fields and high temperature Monte Carlo simulations (MC, 300 K–2000 K, 105 steps) implemented in the HyperChem software. The solvent effect was treated implicitly using distance-dependent dielectric constants. The obtained structures were separated according to the chirality of the sulfoxide center (S- or R- peptides). For each diastereomer, the top 200 structures from each force field were selected and all 400 structures were optimized using density functional theory (DFT) method of PBE1PBE with 6–31 G* basis set. The popular PBE1PBE (also called PBE0) functional was found to be among the best for describing non-covalent interactions, especially H-bonding48. After removing nearly identical ones in the pool of optimized structures, the remaining structures within 5 kcal/mol were further optimized using PBE1PBE/6–31 + G**. All QM calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 software48.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Simulations were performed using AMBER10 software package with AMBER99SB43 force field, a modified Generalized Born solvation44 model. The missing force field parameters of the linkers were obtained from GAFF forcefield, and partial charges were calculated using Jaguar. All non-bonded interactions were evaluated at every 1.0 fs time step. The temperature in each simulation was kept constant using Langevin dynamics with the collision frequency of 1.0 ps-1. The initial structures were alpha-helices with linkers built by Maestro. To remove the bias of the initial structure, each peptide was simulated using regular MD for 10 ns. The final structure of the simulation was used for replica exchange MD (REMD)46 simulations. The conformations of the peptides were generated using REMD simulation method implemented in AMBER10. Eight replicas of the system were simulated simultaneously at temperatures 270, 300, 334, 372, 414, 461, 513, 571 K. At intervals of 10 ps, exchanges were attempted among conformations of the replicas at neighboring temperatures. The REMD simulations were carried out for 20 ns (a total of 160 ns simulation) and 20,000 snapshots were saved for each temperature. Conformations collected at 300 K were used for further analysis.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhang, Q. et al. Chiral Sulfoxide-Induced Single Turn Peptide α-Helicity. Sci. Rep. 6, 38573; doi: 10.1038/srep38573 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Jochim, A. L. & Arora, P. S. Assessment of helical interfaces in protein-protein interactions. Mol. BioSyst. 5, 924–926 (2009).

Jochim, A. L. & Arora, P. S. Systematic analysis of helical protein interfaces reveals targets for synthetic inhibitors. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 919–923 (2010).

Chène, P. Drugs Targeting Protein–Protein Interactions. ChemMedChem 1, 400–411 (2006).

Modell, A. E., Blosser, S. L. & Arora, P. S. Systematic Targeting of Protein–Protein Interactions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 37, 702–713 (2016).

Phillips, C. et al. Design and structure of stapled peptides binding to estrogen receptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9696–9699 (2011).

Arkin, M. R. & Wells, J. A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein–protein interactions: progressing towards the dream. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 301–317 (2004).

Arkin, M. R., Tang, Y. & Wells, J. A. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Protein-Protein Interactions: Progressing toward the Reality. Chem. Biol. 21, 1102–1114 (2014).

Thiel, P., Kaiser, M. & Ottmann, C. Small-molecule stabilization of protein-protein interactions: an underestimated concept in drug discovery? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2012–2018 (2012).

Scott, D. E., Bayly, A. R., Abell, C. & Skindmor, J. Small molecules, big targets: drug discovery faces the protein-protein interaction challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 533–550 (2016).

Yin, H. & Hamilton, A. D. Strategies for targeting protein-protein interactions with synthetic agents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4130–4163 (2005).

Bird, G. H., Crannell, W. C. & Walensky, L. D. Chemical synthesis of hydrocarbon-stapled peptides for protein interaction research and therapeutic targeting. Curr. Prot. Chem. Biol. 3, 99–117 (2011).

Walensky, L. D. & Bird, G. H. Hydrocarbon-stapled peptides: principles, practice, and progress. J. Med. Chem. 57, 6275–6288 (2014).

Spokoyny, A. M. et al. A perfluoroaryl-cysteine S(N)Ar chemistry approach to unprotected peptide stapling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5946–5949 (2013).

Blackwell, H. E. & Grubbs, R. H. Highly Efficient Synthesis of Covalently Cross-Linked Peptide Helices by Ring-Closing Metathesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 3281–3284 (1998).

Marqusee, S. & Baldwin, R. L. Helix stabilization by Glu−…Lys+ salt bridges in short peptides of de novo design. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 84, 8898–8902 (1987).

Meyer, F.-M. et al. Biaryl-bridged macrocyclic peptides: conformational constraint via carbogenic fusion of natural amino acid side chains. J. Org. Chem. 77, 3099–3114 (2012).

Bock, J. E., Gavenonis, J. & Kritzer, J. A. Getting in shape: controlling peptide bioactivity using conformational constraints. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 488–499 (2013).

Kemp, D. S. Peptidomimetics and the template approach to nucleation of beta-sheets and alpha-helices in peptides. Trends Biotechnol. 8, 249–255 (1990).

Mahon, A. B. & Arora, P. S. End-Capped α-Helices as Modulators of Protein Function. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 9, e57–e62 (2012).

Fremaux, J. et al. α-Peptide–Oligourea Chimeras: Stabilization of Short α-Helices by Non-Peptide Helical Foldamers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9816–9820 (2015).

Hoang, H. N. et al. Helix Nucleation by the Smallest Known α-Helix in Water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8275–8279 (2016).

García-Echeverría, C., Chène, P., Blommers, M. J. & Furet, P. Discovery of potent antagonists of the interaction between human double minute 2 and tumor suppressor p53. J. Med. Chem. 43, 3205–3208 (2000).

Banerjee, R., Basu, G., Chène, P. & Roy, S. Aib-based peptide backbone as scaffolds for helical peptide mimics. J. Pept. Res. 60, 88–94 (2002).

Mullard, A. Protein-protein interaction inhibitors get into the groove. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 173–175 (2012).

Estieu-Gionnet, K. & Guichard, G. Stabilized helical peptides: overview of the technologies and therapeutic promises. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 6, 937–963 (2011).

Craik, D. J., Fairlie, D. P., Liras, S. & Price, D. The future of peptide-based drugs. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 81, 136–147 (2013).

Kutchukian, P. S., Yang, J. S., Verdine, G. L. & Shakhnovich, E. I. All-atom model for stabilization of alpha-helical structure in peptides by hydrocarbon staples. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4622–4627 (2009).

Muppidi, A., Wang, Z., Li, X., Chen, J. & Lin, Q. Achieving cell penetration with distance-matching cysteine cross-linkers: a facile route to cell-permeable peptide dual inhibitors of Mdm2/Mdmx. Chem. Commun. 47, 9396–9398 (2011).

Schafmeister, C. E., Po, J. & Verdine, G. L. An All-Hydrocarbon Cross-Linking System for Enhancing the Helicity and Metabolic Stability of Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 5891–5892 (2000).

Jackson, D. Y., King, D. S., Chmielewski, J., Singh, S. & Schultz, P. G. General approach to the synthesis of short alpha-helical peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 9391–9392 (1991).

Lau, Y. H. et al. Functionalised staple linkages for modulating the cellular activity of stapled peptides. Chem. Sci. 5, 1804–1809 (2014).

Zhang, Q., Shi, X., Jiang, Y. & Li, Z. Influence of α-methylation in constructing stapled peptides with olefin metathesis. Tetrahedron 70, 7621–7626 (2014).

Tian, Y. et al. Stapling of unprotected helical peptides via photo-induced intramolecular thiol–yne hydrothiolation. Chem. Sci. 7, 3325–3330 (2016).

de Araujo, A. D. et al. Comparative α-helicity of cyclic pentapeptides in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 6965–6969 (2014).

Hu, K. et al. An in-tether chiral center modulates peptides’ helicity, cell permeability and target binding affinity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8013–8017 (2016).

Speltz T. E. et al. Stapled Peptides with γ-Methylated Hydrocarbon Chains for the Estrogen Receptor/Coactivator Interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 4252–4255 (2016).

Shepherd, N. E., Hoang, H. N., Abbenante, G. & Fairlie, D. P. Single turn peptide alpha helices with exceptional stability in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 2974–2983 (2005).

Aimetti, A. A., Shoemaker, R. K., Lin, C. C. & Anseth, K. S. On-resin peptide macrocyclization using thiol-ene click chemistry. Chem. Commun. 46, 4061–4063 (2010).

Boal, A. K. et al. Facile and E-selective intramolecular ring-closing metathesis reactions in 3(10)-helical peptides: a 3D structural study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6986–6987 (2007).

Modena, G., Quintily, U. & Scorrano, G. Novel route to racemization of sulfoxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 202–208 (1972).

Walther, D. & Cohen, F. E. Conformational attractors on the Ramachandran map. Acta Crystallogr. D 55, 506–517 (1999).

Liu, J., Wang, D., Zheng, Q., Lu, M. & Arora, P. S. Atomic structure of a short alpha-helix stabilized by a main chain hydrogen-bond surrogate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 4334–4337 (2008).

HyperChem(TM) Release 8.0.9 for Windows. Hypercube Inc., Gainesville, FL. http://www.hyper.com/ (2011).

Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6158–6170 (1999).

Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396 (2009).

Mitsutake, A., Sugita, Y. & Okamoto, Y. Generalized-ensemble algorithms for molecular simulations of biopolymers. Pept. Sci. 60, 96–123 (2001).

Hornak, V. et al. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins 65, 712–725 (2006).

Onufriev, A., Bashford, D. & Case, D. A. Exploring protein native states and large-scale conformational changes with a modified generalized born model. Proteins 55, 383–394 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 21102007 and 21372023, the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee SW201110018, SGLH20120928095602764, Pfizer-Peking University platform to Z. G. L.; the Shenzhen Peacock Program (KQTD201103) to Y. D. W. and Z.G.L. MOST of China 2013CB911501, SZSTI Program KQCX20130627103353535, GGJS20130329180714793 to T.W.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Q.Z. designed and performed peptide syntheses and characterization and grew crystals. J.F. conducted the conformational search and Q.M. calculations and assisted with experimental design. B.C.Z. helped with peptide synthesis and developed the intra-molecular thiolene protocol. L.H.C. and Y.T. helped with peptide synthesis and characterization. M.X. helped with crystal growth and solved the crystal structure. G.B. and Y.W. performed 2DNMR studies, G.G., A.A.M., K.S. and M.T. conducted MD simulations, T.W. helped with crystal growth and solved the crystal structure. M.E.F., D.A.P. and S.L. directed the Pfizer team, designed experiments, and analyzed data, Y.D. designed experimental protocol and directed the computational simulation. Z.G.L. conceived and designed experiments, analyzed data, and directed the overall collaboration. Z.Q.Z., J.F., Y.T., M.E.F., A.M.G., Y.D.W. and Z.G.L. co-wrote the manuscript, with comments and contributions from all authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Jiang, F., Zhao, B. et al. Chiral Sulfoxide-Induced Single Turn Peptide α-Helicity. Sci Rep 6, 38573 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38573

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38573

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.