Abstract

Spectral relaxation from fluorescent probes is a useful technique for determining the dynamics of condensed phases. To this end, we have developed a method based on wide-field spectral fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy to extract spectral relaxation correlation times of fluorescent probes in living cells. We show that measurement of the phase and modulation of fluorescence from two wavelengths permit the identification and determination of excited state lifetimes and spectral relaxation correlation times at a single modulation frequency. For NBD fluorescence in glycerol/water mixtures, the spectral relaxation correlation time determined by our approach exhibited good agreement with published dielectric relaxation measurements. We applied this method to determine the spectral relaxation dynamics in membranes of living cells. Measurements of the Golgi-specific C6-NBD-ceramide probe in living HeLa cells revealed sub-nanosecond spectral dynamics in the intracellular Golgi membrane and slower nanosecond spectral dynamics in the extracellular plasma membrane. We interpret the distinct spectral dynamics as a result of structural plasticity of the Golgi membrane relative to more rigid plasma membranes. To the best of our knowledge, these results constitute one of the first measurements of Golgi rotational dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solvent or dipolar relaxation is a fundamental process that could be conveniently monitored in the condensed phase, where the rate of solvent (dipolar) reorientation is comparable to or slower than the fluorescence lifetime. Chemical as well as biological reactions can be influenced by the rate of dipolar relaxations. Examples range from charge transfer reactions to protein folding and membrane dynamics. From a cell biophysics perspective, one would like to have an experimental measure of these processes within the complex environment of the living cell with an overall goal of generating a dynamic map of the living cell.

Fluorescence offers a physical means to determine dipolar relaxation processes in the vicinity of a fluorescent probe. The emission spectrum of a fluorescent probe undergoes a detectable red shift from the initially excited Franck-Condon (or vertically excited) state to the solvated or relaxed state, if there is a dipole moment difference between ground and excited states. This spectral relaxation can be followed in real time using time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy1,2. Alternatively, the presence of a red-shifted steady state emission spectrum upon excitation at the red edge of the absorption band (called red edge excitation shift or REES) is also a signature of dipolar relaxation on the fluorescence timescale3,4.

A unique feature of the cellular organization is morphological compartmentalization provided by cellular membranes. While the integrity of the cell as a whole is maintained by the outer plasma membrane, thereby providing the cell with its much needed individuality5, the intracellular matter remains spatially localized by a number of organelle membranes (such as Golgi, mitochondrial and nuclear membranes). Although the dynamics of the cellular plasma membrane has been studied by a number of approaches, relatively little information is available on the dynamics of intracellular organelle membranes. The Golgi apparatus is an organelle in the cell that plays an essential role in sorting, processing, modification and trafficking of proteins and lipids6. The Golgi apparatus consists of stacks of flattened disc-shaped membrane-bound compartments called cisternae, which are highly concentrated near the peri-centriolar region of the cell. The Golgi complex functions as a molecular factory in which proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum are chemically processed and sorted for transport to their eventual destination in the cell. Cholesterol concentration has been reported to increase progressively along the cis, medial and trans Golgi stacks, thereby providing a mechanism of protein sorting7. In addition, glycolipids and sphingomyelin are synthesized within the Golgi. The distinctive structure of the Golgi is not a static one but is instead maintained by a steady state dynamic equilibrium of membranes to and from other organelles in the cell. The remarkable structural plasticity and dynamic organization of this organelle eventually contribute to its complex function.

In this paper, we report the spectral relaxation dynamics in Golgi membranes and compare with dynamics in non-Golgi membranes in living cells. To achieve this, we use a Golgi-specific membrane probe, C6-NBD-ceramide8, which preferentially partitions into the membranes of the Golgi apparatus. We utilized fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy with tuneable emission wavelength detection to determine the spatial distribution of the C6-NBD-ceramide probe and its associated excited state dynamics in single HeLa cells. Interestingly, we observed spectral relaxation dynamics in a sub-nanosecond timescale in Golgi membranes, distinct from the plasma membrane where the corresponding dynamics is in nanoseconds. We propose that these altered dynamics in Golgi membranes is related to the complex protein sorting function of the Golgi. To the best of our knowledge, these results constitute one of the early reports on rotational dynamics in Golgi using spectral relaxation imaging microscopy.

Results

Spectral relaxation in viscous solvents

Molecules labelled with the NBD group has been extensively used as fluorescent probes to monitor membrane environment and dynamics due to a number of excellent photophysical properties of the NBD fluorophore9,10. To evaluate the behavior of the NBD fluorophore in a model solvent system, we measured the excited state decay of NBD-X dissolved in glycerol. Figure 1 depicts the phase lifetime (τφ) and modulation lifetime (τm) of NBD-X as a function of emission wavelength. Of particular note is the change in relative magnitude of the phase lifetime compared with the modulation lifetime as the detection wavelength is shifted from the blue to the red region (short to long wavelength) of the emission spectrum. For example, at wavelengths less than 560 nm, τφ is less than τm, whereas τφ is greater than τm at wavelengths greater than 560 nm. As previously shown by Lakowicz and Balter11, this behaviour is characteristic of an excited state process, such as solvent relaxation.

Fluorescence lifetime data for NBD-X in glycerol as a function of emission wavelength.

Lifetimes were derived from the measured phase (τφ, black) and the measured modulation (τm, red) at a frequency of 35 MHz. Note the change in relative magnitude of τφ and τm at wavelengths greater than 560 nm. Temperature was 20 °C.

Figure 2 represents the data of Fig. 1 in the form of a phasor plot where x = mcosφ, and y = msinφ, and m is modulation and φ is phase. Data recorded from the red part of the emission spectrum exhibited an increased phase compared to the blue part of the spectrum, which is consistent with a spectral relaxation process (i.e., a phase delay in the emission from blue to red)12. Interestingly, data obtained from several wavelengths is well approximated by a straight line in phasor space which suggests a two state model is adequate to describe the excited state dynamics in this system. Due to this linearity (R2 = 0.999), we could use data from two wavelengths to extract the relevant decay dynamics (see Fig. 3).

Phasor plot of NBD-X in glycerol for different detection wavelengths.

Data corresponds to 11 FLIM measurements at detection wavelengths ranging from 510 to 620 nm with an increment of 10 nm. Solid line is a fit to a linear function (msinφ = −0.485*mcosφ + 0.704) with R2 = 0.999. Temperature was 20 °C.

Phasor plot for NBD-X in solvents of varying viscosity.

Data shown correspond to 100% glycerol (red line), 97% glycerol/3% water (black line), 90% glycerol/10% water (blue line), 80% glycerol/20% water (brown line), 70% glycerol /30% water (grey line), 50%/50% (purple line). In each set, there are two phasor points (one located outside and one inside of the semi-circle; shown in green) that correspond to detection wavelengths of 600 and 530 nm, respectively. Each of the fitted lines intersect the guiding semi-circle at two points (e.g., T1 and T2 for the red line, as shown in the graph). Temperature was 20 °C.

To provide a quantitative estimate for the rates of spectral relaxation processes, we analyzed the data according to an approximate model for the relaxation processes. This model considers a time-dependent spectral shift in terms of detected emissions at 530 (I530) and 600 (I600) nm and an instrument correction factor G. The Generalized Polarization (GP) is given by:

During spectral relaxation, GP will change from a value corresponding to the Franck-Condon spectrum (GPo) to that of the relaxed spectrum (GP∞). Assuming an exponential time course for the relaxation process with spectral relaxation correlation time Ts, the time-dependent GP function is given by:

Assuming that the depopulation of the excited state is also exponential with lifetime T2 (i.e., Itotal(t) = (I530 + I600)(t) = Io exp(−t/T2)), one can express the time-dependent emissions detected at 530 and 600 nm as:

Substitution of equation (2) into equations (3) and (4) yields equations (5–7):

Equations (5) and (6) reveal that for the simplest model of spectral relaxation considered here, fluorescence dynamics consists of two relaxation times, T1 and T2, but with relative amplitudes which depend on the detection wavelength. In particular, this model predicts (for GPo > GP∞) that data recorded in the blue side of the emission will exhibit double exponential decay in time with a phasor inside the universal circle. Data recorded on the red side of the emission will have a time-dependent rise and decay profile and a phasor outside the universal circle (see Fig. 2). In analogy with other systems displaying excited state dynamics13,14, T1 and T2 can be extracted from analysis of the phasor components recorded at 530 and 600 nm (equations 8, 9):

where w is the modulation frequency (w = 0.2512 ns−1 (40 MHz) or w = 0.22 ns−1 (35 MHz) for our experiments). Note that unlike the determination of the steady-state GP, which requires a G-factor, no G-factor is required to extract the time constants T1 and T2.

Carrying out this analysis for NBD-X in glycerol, the spectral relaxation correlation time (Ts) was found to be 1.88 ± 0.04 ns. The value for Ts obtained from NBD-X excited state dynamics is in agreement (i.e., within 10%) with other reported values obtained using different approaches (Ts = 1.8 ns (NMR)15, Ts = 2 ns (dielectric relaxation)16, Ts = 1.98 ns (theoretical approach)17).

Figure 3 displays phasor plots for NBD-X in glycerol/water mixtures of differing composition recorded at 530 and 600 nm, and the corresponding relaxation times (T2 and T1) are shown. It is clear that adding water decreases the value of T2 and T1, and decreases the value of TS. This is in accordance with previous reports on polarity and hydrogen bonding decreasing the excited state NBD lifetime (decreasing T2)18 and decreased viscosity of glycerol (decreasing TS)16 with increasing water fraction. It is important to note that the phasors for NBD-X recorded at 600 nm for the higher water fractions (Fig. 3) lie at or below the universal circle, which does not strictly conform to the simple model proposed here. Thus the parameters obtained from these datasets should be treated as being approximate.

A comparison of NBD-X spectral relaxation correlation time (Ts) with literature data on glycerol/water mixtures using the principal dielectric relaxation time from dielectric relaxation measurements16 (Tdr) is shown in Fig. 4. The regression line reveals good agreement between the two approaches (y = 1.05x + 0.02; R2 = 0.99 (Fig. 4)). Nevertheless because of the approximations in our method, we suggest that relaxation times greater than 0.5 ns can be reliably measured with our approach.

Taken together, these experiments in glycerol/water solution using a model NBD fluorophore demonstrate that our instrumentation and analysis can provide a quantitative measure of spectral relaxation in the time range of >0.5 ns with a NBD-linked biomolecule. We next turn to the application of these approaches to determining the spectral relaxation behavior of Golgi membranes and plasma membranes in living cells. For this purpose, we use C6-NBD-ceramide, which has been shown previously to be a specific probe for the membrane of Golgi8.

Spectral relaxation of C6-NBD-ceramide in the Golgi and plasma membranes of living cells

Figure 5 shows a representative confocal laser scanning image of a HeLa cell stained with C6-NBD-ceramide. Fluorescence intensity and lifetime images of a typical HeLa cell stained with C6-NBD-ceramide obtained with our wide-field fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) set-up are shown in Fig. 6. As can be seen in Fig. 6A, most of the probe is located in internal structures (resembling Golgi) and excluded from the nucleus. There is weaker fluorescence from the plasma membrane, which can be excluded by applying an intensity threshold. These observations are consistent with previous reports19. Figure 6B,C represents fluorescence lifetime images of the Golgi-stained membranes, Fig. 6D,E non-Golgi membranes, and Fig. 6F,G plasma membrane. When detected at 530 nm, the NBD-ceramide probe has a lifetime of about 7 ± 0.2 ns and the lifetime is largely independent of spatial location as determined from the phase or modulation of the emission. However, differences in fluorescence lifetimes are more evident for the data collected at 600 nm (Fig. 7). In the Golgi, non-Golgi and plasma membranes, the phase lifetime is significantly larger than the modulation lifetime (Δ0.6 ns, Golgi; Δ1.0 ns, non-Golgi; Δ1.0 ns, plasma membrane). This shows the spectral relaxation of C6-NBD-ceramide in HeLa cell membranes. In addition, the extent of relaxation appears to be different in Golgi membranes. Phasor plots corresponding to Figs 6 and 7 are shown in Figs S1–S4 (see Supporting Information).

Fluorescence intensity and lifetime images of a HeLa cell labeled with C6-NBD-ceramide at the blue edge.

Images were acquired with excitation at 470 nm and emission at 530 ± 20.2 nm. (A) Intensity image of cell (color table inset: low, 0 and high, 35,000 arbitrary units). Images in the left column represent modulation lifetime images and images on the right are phase lifetime images. Golgi membrane: (B) τm = 6.99 ns. (C) τφ = 6.79 ns. Golgi-excluded membranes: (D) τm = 6.94 ns. (E) τφ = 7.04 ns. Plasma membranes: (F) τm = 6.97 ns (G) τφ = 7.1 ns. The scale bar represents 10 μm. See text for other details. Temperature was 20 °C.

Fluorescence intensity and lifetime images of a HeLa cell labeled with C6-NBD-ceramide at the red edge.

Images were acquired with excitation at 470 nm and emission at 600 ± 20.8 nm. (A) Intensity image of cell (color table inset: low, 0 and high, 35,000 arbitrary units). Images in the left column represent modulation lifetime images and images on the right are phase lifetime images. Golgi membrane: (B) τm = 7.08 ns. (C) τφ = 7.66 ns. Golgi-excluded membranes: (D) τm = 7.12 ns. (E) τφ = 8.12 ns. Plasma membranes: (F) τm = 7.2 ns (G) τφ = 8.13 ns. The scale bar represents 10 μm. See text for other details. Temperature was 20 °C.

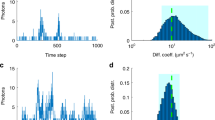

Figure 8 provides a representation of this analysis. In Fig. 8A, we have plotted the phasor clouds corresponding to the pixel-by-pixel data from cells recorded at 530 and 600 nm. The average values of these clouds are shown by the red and blue dots in the main plot in Fig. 8A. Values for T1, T2 and Ts from 10 individual cells are summarized in Fig. 8B. T1 was found to be significantly shorter in Golgi membranes (T1 = 0.8 ns) relative to the corresponding value in non-Golgi regions (T1 = 2 ns) or plasma membrane (T1 = 2 ns). However, T2 values were similar in all detected membranes (T2 ~ 8 ns). As a consequence, Ts in Golgi membranes is much smaller (Ts = 0.8 ns) than that in non-Golgi regions (Ts = 3.5 ns) or plasma membrane (Ts = 2.9 ns). This suggests that spectral relaxation in the membrane interface of Golgi is less restricted (faster) than non-Golgi membranes. These results could have significant implications in the context of Golgi dynamics and function.

(A) Phasor (or polar or AB) plot representation of FLIM measurements. The inset diagrams and associated phasor clouds represent lifetime information from individual cells at pixel resolution. The averages of the phasor clouds (the region-averaged phasors) collected from the blue part (shorter wavelength) of the emission spectrum and the red part (longer wavelength) of the emission spectrum are depicted by the blue dot and red dot in the main diagram, respectively. A linear extrapolation is denoted by the black line with the two component lifetimes, T1 and T2 indicated by the positions of intersection of the line with the semi-circle. Note the position of one of the phasors is outside the semi-circle, indicative of excited state relaxation. (B) Derived lifetimes (T1, T2) and spectral relaxation correlation time (Ts) from Golgi (shown as maroon bars), non-Golgi (blue bars) and plasma membrane (green bars) of 10 individual HeLa cells. The magnitudes of the columns are related to the average value while the error bars represent one standard deviation. Note the significantly faster spectral relaxation in the Golgi membrane (Ts = 0.8 ns) compared to the membranes in the non-Golgi (Ts = 3.5 ns) and plasma membranes of the cells (Ts = 2.9 ns). Temperature was 20 °C.

Discussion

Lateral dynamics in Golgi membranes has been previously studied20,21. On the other hand, rotational dynamics, a better indicator of protein-protein interaction and oligomerization due to weak dependence of lateral diffusion on the mass of the diffusing object in a membrane22, has not been previously explored in Golgi membranes. In this context, our results assume relevance and constitute a novel study in the overall area of organelle membrane dynamics.

We now turn to possible explanations for the observed spectral relaxation dynamics. One possible explanation for the observed spectral relaxation dynamics could be that the NBD probe is located in heterogeneous locations of the lipid bilayer, i.e., in a less polar, longer lifetime environment and a more polar, shorter lifetime environment. For example, NBD-ceramide has been reported to co-exist between liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered domains of membranes23. Herrmann’s laboratory24 has further shown that the excited state lifetime of NBD-C6 is about 11 ns in liquid-ordered domains and 7 ns in liquid-disordered domains. Because the polar environment in the liquid-disordered domains has a red-shifted emission relative to the non-polar environment in the liquid-ordered domains, this would give rise to an apparent spectral shift in time. However, because the blue emission in the liquid-ordered domains is longer lived (11 ns) than the red-shifted polar solvent emission from the liquid-disordered domains (7 ns), this would give rise to a longer phase in the blue part of the emission than in the red. The present data clearly show that the phase of the emission is larger in the red than the blue. A simple ‘population heterogeneity’ model therefore cannot account for our observations in membranes of living cells.

These observations are more consistent with a solvent relaxation model where the spectral relaxation time is related to relaxation of the solvent cage around the newly created NBD excited state due to the increase in dipole moment25 of the NBD group upon excitation. Trivial differences in level of hydration or polarity (as reflected in the lifetime values (T2) for Golgi and plasma membranes) cannot account for the differences in dynamics between Golgi and other membranes, since T2 values are essentially the same in both membranes. Therefore, the most likely conclusion is that the solvation dynamics in the different membranes are intrinsically different.

A possible contributing factor for faster solvent relaxation may lie in the metabolism of the C6-NBD-ceramide which is time-dependent and results in the production of NBD-cerebroside, NBD-sphingomyelin and the relocation of the probe from the Golgi to the plasma membrane26. Although the precise distribution of these different metabolites is unknown, having a different lipid tail may locate the probe in a different transverse or lateral location in the membrane where motional dynamics is altered. For example, a polarity gradient from non-polar to polar begins in the hydrocarbon region of the bilayer and extends out through the membrane interface to the water region. The lipid dynamics also exhibits a motional gradient but in the opposite direction with the membrane interface being most restricted and the hydrocarbon region least restricted3. Another possible contributing factor is the composition of the different membranes. The membrane composition of the Golgi27 and plasma membranes are in turn is related to their biogenic functions. The cis-Golgi is composed of thin bilayers with loose lipid packing and relatively low cholesterol content7. The loose lipid packing could contribute to faster overall rotational dynamics. The plasma membrane, in contrast, contains thick bilayers (due to high amount of cholesterol) with tight lipid packing related to its barrier function.

The analysis and results presented here indicate that spectral relaxation imaging microscopy promises to be a useful tool for quantitative imaging of spectral dynamics in complex environments. Our method provides quantitative estimates of excited state lifetimes and spectral relaxation correlation times from image data collected at two wavelength regions. The frequency-domain wide-field FLIM approach is characterized by fast acquisition, making it suitable for live cell imaging where reduction in light dose and tracking of processes in biological timescales are desired. It is important to emphasize that the analysis presented here is based on a simple model and only yields an apparent spectral relaxation time. For many systems undergoing spectral relaxation the correlation functions are typically non-exponential and characterized by the sum of two or more exponentially-decaying processes28,29. The interpretation of faster or slower dynamics could therefore also be interpreted as changes in the proportion of faster processes relative to slower processes. We have simulated the cases of two spectral relaxation times and one lifetime and found that the apparent spectral relaxation time obtained from our analysis is intermediate between the amplitude-weighted average of the two spectral relaxation times and the fluorescence-weighted average of the two spectral relaxation times (data not shown). We therefore believe that our model, although approximate, provides a useful parameter even in complex dynamic situations.

There is a wealth of studies on model membranes30,31,32,33,34,35,36 and an emerging literature12,36,37,38 on the use of dynamic imaging approaches to measure spectral relaxation in living cells. At the time this work was being completed, the Gratton laboratory12 published a phasor-based approach to measure membrane polarity and microviscosity. The phasor in the blue part of the spectrum was used to examine polarity or hydration, while the phasor in the green (longer wavelength) part of the spectrum was used to examine solvent dipolar dynamics12. Changes in polarity or microviscosity in living cells were inferred relative to measurements on model membranes of differing cholesterol content or phase state.

Further work is needed to understand dipolar solvent dynamics in membranes of living cells. A future goal is to understand the factors influencing solvent dynamics in complex environments and whether solvent relaxation can be used as a biosensor for detection of organelle-affected diseases. Since impairment of Golgi function appears to be linked to several diseases39, it is possible that these impairments could influence solvent relaxation times. At present, we are actively pursuing investigations along these lines.

Methods

Fluorescent membrane probe stock preparation

C6-NBD-ceramide (N-[6-[(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino]hexanoyl]-D-erythro-sphingosine) (Avanti Polar Lipids; Alabaster, AL) was used as a fluorescent lipid. 10 μl of chloroform solution of the fluorescent lipid was dried and dissolved in 1 ml DMEM to give a concentration of 5.75 μM of stock solution of C6-NBD-ceramide. The solution was vortexed and kept at 4 °C before use.

Cell culture and treatments

HeLa Cells were cultured in a flask for 2 days in DMEM (+HEPES + 5–10% FCS + 1:100 Glutamate in 10% CO2) at 37 °C in CO2 incubator. After splitting, cells were freshly plated onto chambered coverglass (Lab-Tek II; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Rochester, NY) and were incubated for 1 day. Cells were first rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice. Cells were then labelled with C6-NBD-ceramide by incubating the cells for 30 minutes at 37 °C with a solution containing 1 ml DMEM and 40 μl of prepared stain solution (final concentration of 0.2 μM C6-NBD-ceramide). Prior to imaging, the cells were washed twice with DMEM.

Solution experiments

The solvent relaxation of NBD-X (6-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)hexanoic acid) (AnaSpec Inc; Fremont, CA) was measured in glycerol and in glycerol/water mixtures. NBD-X was dissolved in glycerol at a concentration of 31.25 μM. Solutions of NBD-X in glycerol/water were prepared by mixing different volumes of water with the glycerol/NBD-X solution. NBD-X in glycerol/water mixtures contained 0, 3, 10, 20 30 and 50% (v/v) water.

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy

A Nikon microscope (Model Ti, Nikon, Japan) with Lambert instruments LIFA (Leutingwolde, The Netherlands) FLIM attachment was employed to measure FLIM images of HeLa cells. Samples were excited with sinusoidally-modulated (35 MHz) 474 nm light focused through a 100x/1.4NA oil objective and emission was observed through a hyper-spectral imaging system (His-400; Gooch & Housego; Orlando, FL) set at 530 ± 20.2 nm and 600 ± 20.8 nm, respectively. Twelve phase steps were recorded in pseudo-random order by using software provided by the manufacturer. Rhodamine 6 G in distilled water (lifetime = 4.1 ns) was used as a reference40. Lambert LI-FLIM software was used for analysis of experimental data. The phasor plots were exported using the Lambert LI-FLIM software. To measure lifetime of solutions in a cuvette, a 40x/0.7NA air objective was employed.

Image analysis of FLIM data

The FLIM microscope produces wide-field images of fluorescence from the whole cell. Intensity thresholding was used to isolate fluorescence from the Golgi, non-Golgi or outer plasma membrane. C6-NBD-ceramide preferentially partitions to membranes of the Golgi apparatus but is also visible, to a lesser extent, in other cellular membranes including the plasma membrane. In this condition, non-Golgi membrane fluorescence was excluded with an intensity threshold to display pixels only with fluorescence signal above a certain threshold. Conversely, the plasma membrane regions were revealed by lowering the minimum intensity threshold and including an upper threshold on intensity values to exclude fluorescence from the internal membranes. Thresholding and FLIM analysis was performed using the LI-FLIM software.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

An Olympus FV1000 scanning laser confocal microscope was used to confirm Golgi localization of the C6-NBD-ceramide in HeLa cells. Excitation of the dye was provided with the 488 nm laser line focused through a 100x oil objective. Dye fluorescence was detected through a bandpass filter in the wavelength range 500–530 nm.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lajevardipour, A. et al. Imaging Cellular Dynamics with Spectral Relaxation Imaging Microscopy: Distinct Spectral Dynamics in Golgi Membranes of Living Cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 37038; doi: 10.1038/srep37038 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Maroncelli, M. & Fleming, G. R. Picosecond solvation dynamics of coumarin 153: the importance of molecular aspects of solvation. J. Chem. Phys. 86, 6221–6239 (1987).

Jurkiewicz, P., Sýkora, J., Olżyńska, A., Humpolíčková, J. & Hof, M. Solvent relaxation in phospholipid bilayers: principles and recent applications. J. Fluoresc. 15, 883–894 (2005).

Haldar, S., Chaudhuri, A. & Chattopadhyay, A. Organization and dynamics of membrane probes and proteins utilizing the red edge excitation shift. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 5693–5706 (2011).

Chattopadhyay, A. & Haldar, S. Dynamic insight into protein structure utilizing red edge excitation shift. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 12–19 (2014).

Budin, I. & Szostak, J. W. Expanding roles for diverse physical phenomena during the origin of life. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 39, 245–263 (2010).

Mellman, I. & Simons, K. The Golgi complex: in vitro veritas? Cell 68, 829–840 (1992).

Bretscher, M. S. & Munro, S. Cholesterol and the Golgi apparatus. Science 261, 1280–1281 (1993).

Lipsky, N. G. & Pagano, R. E. A vital stain for the Golgi apparatus. Science 228, 745–747 (1985).

Chattopadhyay, A. Chemistry and biology of N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl) labeled lipids: fluorescence probes of biological and model membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 53, 1–15 (1990).

Haldar, S. & Chattopadhyay, A. Application of NBD-labeled lipids in membrane and cell biology. Springer Ser. Fluoresc. 13, 37–50 (2013).

Lakowicz, J. R. & Balter, A. Analysis of excited-state processes by phase-modulation fluorescence spectroscopy. Biophys. Chem. 16, 117–132 (1982).

Golfetto, O., Hinde, E. & Gratton, E. Laurdan fluorescence lifetime discriminates cholesterol content from changes in fluidity in living cell membranes. Biophys. J. 104, 1238–1247 (2013).

Clayton, A. H. A. The polarized AB plot for the frequency-domain analysis and representation of fluorophore rotation and resonance energy homotransfer. J. Microsc. 232, 306–312 (2008).

Clayton, A. H. A., Hanley, Q. S. & Verveer, P. J. Graphical representation and multicomponent analysis of single-frequency fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy data. J. Microsc. 213, 1–5 (2004).

Kintzinger, J. P. & Zeidler, M. D. Nuclear magnetic relaxation study of glycerol. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 77, 98–103 (1973).

Behrends, R., Fuchs, K., Kaatze, U., Hayashi, Y. & Feldman, Y. Dielectric properties of glycerol/water mixtures at temperatures between 10 and 50 °C. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 144512 (2006).

Ngai, K. L. & Tsang, K. Y. Similarity of relaxation in supercooled liquids and interacting arrays of oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 60, 4511–4517 (1999).

Lin, S. & Struve, W. S. Time-resolved fluorescence of nitrobenzoxadiazole-aminohexanoic acid: effect of intermolecular hydrogen-bonding on non-radiative decay. Photochem. Photobiol. 54, 361–365 (1991).

Pagano, R. E., Sepanski, M. A. & Martin, O. C. Molecular trapping of a fluorescent ceramide analogue at the Golgi apparatus of fixed cells: interaction with endogenous lipids provides a trans-golgi marker for both light and electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 109, 2067–2079 (1989).

Cole, N. B., Smith, C. L., Sciaky, N., Terasaki, M., Edidin, M. & Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Diffusional mobility of Golgi proteins in membranes of living cells. Science 273, 797–801 (1996).

Sengupta, P. & Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Photohighlighting approaches to access membrane dynamics of the Golgi apparatus. Methods Cell Biol. 118, 217–234 (2013).

Saffman, P. G. & Delbrück, M. Brownian motion in biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72, 3111–3113 (1975).

Sot, J., Ibarguren, M., Busto, J. V., Montes, L.-R., Goñi, F. M. & Alonso, A. Cholesterol displacement by ceramide in sphingomyelin-containing liquid-ordered domains, and generation of gel regions in giant lipidic vesicles. FEBS Lett. 582, 3230–3236 (2008).

Stöckl, M., Plazzo, A. P., Korte, T. & Herrmann, A. Detection of lipid domains in model and cell membranes by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy of fluorescent lipid analogues. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30828–30837 (2008).

Mukherjee, S., Chattopadhyay, A., Samanta, A. & Soujanya, T. Dipole moment change of NBD group upon excitation studied using solvatochromic and quantum chemical approaches: implications in membrane research. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 2809- 2812 (1994).

Lipsky, N. G. & Pagano, R. E. Sphingolipid metabolism in cultured fibroblasts: Microscopic and biochemical studies employing a fluorescent ceramide analogue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 80, 2608–2612 (1983).

van Meer, G., Voelker, D. R. & Feigenson, G. W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 112–124 (2008).

Bismuto, E., Irace, G., Colonna, G., Jameson, D. M. & Gratton, E. Dynamic aspects of the heme-binding site in phylogenetically distant myoglobins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 913, 150–154. (1987).

Hutterer, R., Schneider, F. W., Lanig, H. & Hof, M. Solvent relaxation behaviour of n-anthroyloxy fatty acids in PC-vesicles and paraffin oil: a time-resolved emission spectra study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1323, 195–207 (1997).

Viard, M., Gallay, J., Vincent, M., Meyer, O., Robert, B. & Paternostre, M. Laurdan Solvatochromism: Solvent Dielectric Relaxation and Intramolecular Excited-State Reaction. Biophys. J. 73, 2221–2234 (1997).

Bagatolli, L. A., Parasassi, T., Fidelio, G. D. & Gratton, E. A model for the interaction of 6-lauroyl-2-(n,ndimethylamino)naphthalene with lipid environments: implications for spectral properties. Photochem. Photobiol. 70, 557–564 (1999).

Vincent, M., de Foresta, B. & Gallay, J. Nanosecond dynamics of a mimicked membrane-water interface observed by time-resolved stokes shift of LAURDAN. Biophys. J. 88, 4337–4350 (2005).

Raghuraman, H. & Chattopadhyay, A. Orientation and dynamics of melittin in membranes of varying composition utilizing NBD fluorescence. Biophys. J. 92, 1271–1283 (2007).

Lúcio, A. D., Vequi-Suplicy, C., Fernandez, R. N. & Lamy, M. Laurdan spectrum decomposition as a tool for the analysis of surface bilayer structure and polarity: a study with DMPG, peptides and cholesterol. J. Fluoresc. 20, 473–482 (2010).

Dinic, J., Biverståhl, H., Mäler, L. & Parmryd, I. Laurdan and di-4-ANEPPDHQ do not respond to membrane-inserted peptides and are good probes for lipid packing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 298–306 (2011).

Parasassi, T., Gratton, E., Yu, W. M., Wilson, P. & Levi, M. Two-photon fluorescence microscopy of laurdan generalized polarization domains in model and natural membranes. Biophys. J. 72, 2413–2429 (1997).

Owen, D. M. & Gaus, K. Optimized time-gated generalized polarization imaging of Laurdan and di-4-ANEPPDHQ for membrane order image contrast enhancement. Microsc. Res. Tech. 73, 618–622. (2010).

Owen, D. M., Williamson, D. J., Magenau, A. & Gaus, K. Sub-resolution lipid domains exist in the plasma membrane and regulate protein diffusion and distribution. Nat. Commun. 3, 1256, (2012).

Bexiga, M. G. & Simpson, J. C. Human diseases associated with form and function of the Golgi complex. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 18670–18681 (2013).

Hanley, Q. S., Subramaniam, V., Arndt-Jovin, D. J. & Jovin, T. M. Fluorescence lifetime imaging: multi-point calibration, minimum resolvable differences, and artifact suppression. Cytometry 43, 248–260 (2001).

Acknowledgements

A.C. gratefully acknowledges a Visiting Professorship from Swinburne University of Technology and J.C. Bose Fellowship from the Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India. A.H.A.C. acknowledges ARC funding through DP110100164 grant. A.C. is an Adjunct Professor of Swinburne University of Technology. We sincerely thank Sreetama Pal and Parijat Sarkar for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L. and J.W.M.C. performed experiments and analyzed data; A.C. and A.H.A.C. designed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lajevardipour, A., Chon, J., Chattopadhyay, A. et al. Imaging Cellular Dynamics with Spectral Relaxation Imaging Microscopy: Distinct Spectral Dynamics in Golgi Membranes of Living Cells. Sci Rep 6, 37038 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37038

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37038

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic cellular maps of molecular species: Application to drug-target interactions

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.