Abstract

In this study, a fixed-site field experiment was conducted to study the influence of different combinations of tillage and straw incorporation management on carbon storage in different-sized soil aggregates and on crop yield after three years of rice-wheat rotation. Compared to conventional tillage, the percentages of >2 mm macroaggregates and water-stable macroaggregates in rice-wheat double-conservation tillage (zero-tillage and straw incorporation) were increased 17.22% and 36.38% in the 0–15 cm soil layer and 28.93% and 66.34% in the 15–30 cm soil layer, respectively. Zero tillage and straw incorporation also increased the mean weight diameter and stability of the soil aggregates. In surface soil (0–15 cm), the maximum proportion of total aggregated carbon was retained with 0.25–0.106 mm aggregates, and rice-wheat double-conservation tillage had the greatest ability to hold the organic carbon (33.64 g kg−1). However, different forms occurred at higher levels in the 15–30 cm soil layer under the conventional tillage. In terms of crop yield, the rice grown under conventional tillage and the wheat under zero tillage showed improved equivalent rice yields of 8.77% and 6.17% compared to rice-wheat double-cropping under zero tillage or conventional tillage, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, soil stores approximately 1,500 Pg of carbon in the form of organic carbon. The soil organic carbon (SOC) pool is 2.5 and 2 times the carbon pool in terrestrial vegetation and the atmosphere, respectively1. Thus, small changes in soil organic carbon can cause dramatic changes in the concentration of atmospheric CO22. Before this problem was recognized, the primary purpose of soil tillage was to create suitable soil environmental conditions for crop growth, to conserve soil water, and to promote crop-yield increases3. However, with the increased awareness of the greenhouse effect, soil organic carbon has been found to be easily affected by tillage and fertilization, and various tillage practices were found to exert a significant influence on soil disturbances, aggregate stability, and organic carbon flux rates4,5,6. Thus, the purpose of soil tillage was no longer limited to increasing crop yields, and a greater consideration was given to the efficacy of enhancing soil carbon preservation and preventing the occurrence of greenhouse effects7,8.

Extensive studies have shown that compared to conventional tillage, conservation tillage (including zero tillage, minimum tillage, and straw incorporation) can be effective in reducing soil disturbances and soil aggregate structure destruction. Conservation tillage can also slow the turnover rate of macroaggregates, prevent the decomposition of organic carbon by microbes, and extend the storage period of organic carbon in aggregates9,10,11. However, numerous studies hold the opposite view. For example, Carter12 and Blanco-Canquia13 believe that conservation tillage induces less carbon storage than conventional tillage throughout the soil profile. Thus, whether conservation tillage can increase organic carbon storage in the soil remains an important issue despite extensive studies that have investigated the influence of various tillage practices and field management measures on the content and storage of soil organic carbon14,15,16,17. Moreover, previous research has primarily investigated a particular type of crop in dryland or paddy fields18,19,20, and limited research has been conducted under a background of paddy-dryland rotation. The use of any tillage measure affects the soil’s physicochemical properties and crop yields at various levels. Additionally, the long-term application of a single tillage measure results in unfavourable soil conditions for crop growth21. Therefore, it is unclear whether conventional tillage or zero tillage and straw incorporation with conservation tillage can satisfy the demand of both ecological and production benefits, namely, increasing the capacity of soil carbon preservation and improving crop yields.

In this study, we chose a rice-wheat double cropping system from a rice-wheat cropping area. A fixed-site field experiment was performed in three consecutive years to achieve the following objectives: (1) to determine the influence of various tillage practices and straw incorporation on the soil aggregate percentage distribution, aggregate stability, and associated organic carbon preservation under rice-wheat rotation; (2) to determine the influence of various tillage practices and straw incorporation on rice-wheat yields and yield components under rice-wheat rotation; and (3) to provide evidence for the development of a reasonable tillage management model in rice-wheat cropping areas.

Results

Size composition of the soil aggregates

Table 1 presents the test results of the aggregate size composition in the soil samples collected in November 2013. Under the influence of different tillage practices and straw incorporation measures, the percentage of aggregates of different size classes significantly varied in the topsoil (0–15 cm) and subsurface (15–30 cm) layers. Zero tillage increased the percentage of macroaggregates and water-stable macroaggregates in the soil. In the 0–15 cm soil layer, the mean percentage of A1 was 12.77% higher for the three rice-wheat under zero tillage (RWzt) treatments (T1, T2, and T3) compared to the rice-wheat under conventional tillage (RWct) treatments (T7, T8, and T9). The increase in the percentage of WSA1 was 43.21%. The same trend was observed in the 15–30 cm soil layer. Moreover, the percentage of WSA2 was significantly higher for the RWzt treatment than for the RWct treatment and the treatment of rice under conventional tillage + wheat under zero tillage (RctWzt); the increases were 24.90% and 17.90% in the 0–15 cm soil layer and up to 39.35% and 33.45% in the 15–30 cm soil layer. Under the same tillage practice, the percentage of soil aggregates did not show significant differences among the three treatments of straw incorporation regardless of the depth (0–15 cm or 15–30 cm). However, the percentages of WSA1 and WSA2 in the treatments were ranked as follows: rice-wheat straw incorporation (RWsi) > wheat straw incorporation (Wsi) > no straw incorporation (Nsi). The highest percentages of A1 and WSA1 were observed for the RWzt + RWsi (T3). These high values were higher than those obtained for the RWct + Nsi (T7) by 17.22% and 36.39% in the 0–15 cm soil layer and 28.93% and 66.34% in the 15–30 cm soil layer.

Soil aggregate-associated organic carbon

As shown in Table 2, regardless of the results obtained by dry or wet sieving, the SOC concentration in the aggregates of various size classes was markedly higher in the 0–15 cm layer compared to that in the 15–30 cm soil layer. Among the various size classes, the SOC concentration in the dry-sieved aggregates was highest for M1 in the 0–15 cm soil layer, which had a mean of 31.08 g·kg−1 for the different treatments. In addition, the aggregate-associated SOC generally occurred at similar levels in the other three size classes (A1, A2, and <0.106 mm aggregates (P2)) and had means of 21.28, 22.20, and 20.05 g·kg−1, respectively. The SOC concentrations in the water-stable aggregates obtained by wet sieving were ranked as follows: WSA2 > WSM1 > WSA1, with means of 25.14, 23.34, and 20.54 g·kg−1. Compared to the 0–15 cm soil layer, limited differences were observed for the aggregate-associated SOC concentrations between various size classes in the 15–30 cm soil layer, and the mean of the different treatments ranged from 10.42 to 11.77 g·kg−1.

For the different treatments, the aggregate-associated SOC concentration in the 0–15 cm soil layer ranked higher in the RWzt treatment than in the RctWzt treatment group and RWct treatment group. In addition, the two treatment groups with straw incorporation produced higher aggregate-associated SOC concentrations than the treatment without straw incorporation. The dry sieving results showed that the aggregate-associated SOC concentrations in the A1, A2, and M1 size classes were significantly higher in the RWzt treatment group than in the RWct treatment group (F = 8.265, 5.483, and 10.326, respectively); however, significant differences were not observed between the RctWzt treatment group and the above two groups. The above trend was more obvious in the water-stable aggregates. This result indicates that the double crop under zero tillage was conducive to improving the aggregate-associated SOC concentrations. For the double crop under zero tillage groups, the SOC concentrations of the aggregates of various size classes were significantly higher for the double crop (T3) and single-crop straw incorporation (T2) treatments compared to the no straw incorporation (T1) group regardless of the results obtained by dry or wet sieving. Similarly, the same trend was observed in the RWct and RctWzt treatment groups. In particular, the T3 treatment with RWzt + RWsi resulted in higher SOC concentrations in the aggregates of various size classes compared to the other treatments. According to the results of dry sieving, the aggregate-associated SOC concentrations in the A1, A2, and M1 size classes were higher than those under the T7 treatment with differences of 12.90%, 26.50%, and 17.74%, respectively, which reached statistical significance. The differences between the treatments were more significant in the results obtained by wet sieving. The aggregate-associated SOC concentrations in WSA1, WSA2, and WSM13 were higher under the T3 treatment compared to those under the T7 treatment by 25.04%, 28.55%, and 18.12%, respectively.

In the 15–30 cm soil layer, the aggregate-associated SOC concentration under the different tillage practices presented the following rank: RWct > RctWzt > RWzt, which differed from the trend in the 0–15 cm soil layer. For the three treatments without straw incorporation (T7, T4, and T1), the mean SOC concentrations in the dry-sieved aggregates of the various size classes were 11.22, 10.35, and 10.19 g·kg−1, respectively, and in the wet-sieved aggregates, they were 11.60, 10.83, and 10.33 g·kg−1, respectively. The mean values obtained by both methods were markedly higher for T7 than for T4 and T1. Under the same tillage practice, straw incorporation increased the aggregate-associated SOC concentrations in the 15–30 cm soil layer. For the three treatments with rice-wheat under conventional tillage (T7, T8, and T9), the total SOC concentrations in the aggregates of various size classes under the dry sieving method were 11.22, 12.42, and 12.44 g·kg−1, respectively, whereas the SOC concentrations in water-stable aggregates were 11.60, 12.14, and 12.33 g·kg−1, respectively. The values of the T9 treatment with double-crop straw incorporation and the T8 treatment with single-crop straw incorporation were markedly higher than those of the T7 treatment without straw incorporation. Similar trends were observed in the results obtained for the other two tillage practices.

Crop yields

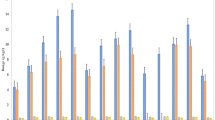

According to the crop yields from the six crop seasons over three years (Fig. 1), the mean rice yield of the nine treatments in 2011 was 8,173.99 kg/hm2, and the coefficient of variance (CV) was 3.34%. The highest rice yield was found for the T4 treatment with RctWzt, 8,763.15 kg/hm2. The lowest rice yield was found for the T1 treatment with RWzt, 7,699.67 kg/hm2. In 2012, the rice yields varied between 7,534.20 and 8,651.60 kg/hm2 and presented a mean of 8,063.15 kg/hm2 and a CV of 4.84%. There were more significant differences between treatments in 2012 than in 2011. In 2013, the rice yields of the various treatments ranged from 7,232.85 to 9,457.51 kg/hm2, the mean was 8326.16 kg/hm2, and the CV was 7.82%. Under the different tillage practices, the mean rice yields were 8,669.14 kg/hm2 for the RctWzt treatment group and 8,554.94 kg/hm2 for the RWct treatment group. These two values were significantly higher than the mean rice yield from the WRzt treatment group (F = 8.206, P < 0.05). This result indicates that conventional tillage was more conducive to increasing rice yields. In particular, the tillage model wherein wheat under zero tillage precedes rice under conventional tillage could increase rice yields. With regard to straw incorporation, the mean rice yields were 8,640.92 and 8,525.47 kg/hm2 for the treatment groups of no straw incorporation and wheat straw incorporation + no rice straw incorporation, respectively. These two values were significantly higher than the mean rice yield from the treatment group of double-crop straw incorporation (F = 9.148, P < 0.05). This result indicates that straw incorporation for both crops after the harvest could reduce rice yields.

For wheat (Fig. 2), the yields of the nine treatments ranged from 6,196.45 to 6,289.05 kg/hm2 in the year 2011, the mean was 6,248.86 kg/hm2, and the CV was 1.14%. In 2012, the wheat yields of the treatments varied between 5,379.75 and 6,546.30 kg/hm2, the mean was 6,162.04 kg/hm2, and the CV was 4.73%. In 2013, the wheat yields of the various treatments fell in the range of 5,391.06–6,920.18 kg/hm2, the mean was 6,200.26 kg/hm2, and the CV was 6.37%. A comparison of the tillage treatments showed that from 2012, the wheat yields ranked as follows: RctWzt > RWzt > RWct. In 2013, the mean wheat yields for the above three treatments were 6,562.94, 6,246.13, and 5,791.69 kg/hm2, respectively, which showed significant differences between tillage practices (F = 24.015, P < 0.05). This result indicates that sowing rice under zero tillage could improve the following wheat yields. In particular, wheat under zero tillage + rice under conventional tillage resulted in the highest wheat yield in the following harvest, whereas rice under conventional tillage caused a yield reduction in the following wheat harvest. With respect to straw incorporation, the following trend was found in wheat yields under the same tillage practice from 2012: Nsi > Wsi > RWsi. In 2013, however, the mean wheat yields for the above three treatments were 6,331.44, 6,257.57, and 6,011.75 kg/hm2, respectively, which showed no significant differences.

Crop yield components

The results of the rice yield components in 2013 (Table 3) showed that different tillage practices primarily affected the effective panicle number and grain number per panicle in rice. The results of the ANOVA showed that effective panicle number was higher for the RctWzt and RWct treatment groups than for the RWzt treatment group. The differences among the above treatment groups was statistically significant (F = 5.633, P < 0.05). The grain number per panicle showed a similar trend. The mean grain number per panicle was highest for the treatment group of RWct and lowest for the treatment group of RWzt. There was a significant difference between the above two treatments (F = 5.372, P < 0.05). The results indicate that conventional tillage could increase the effective panicle number and grain number per panicle in rice, which were the two main factors leading to increases in rice yields. The analysis of straw incorporation revealed that the effective panicle number was markedly lower with double-crop straw incorporation compared to no straw incorporation, and the difference was statistically significant (F = 2.710, P < 0.05). However, significant differences were not obtained between wheat straw incorporation and the above two treatments. Moreover, the different straw incorporation measures caused no significant differences in the grain number per panicle, 1000-grain weight, or seed setting rate. This result indicates that excessive straw incorporation in two consecutive crop seasons was not favourable for straw decomposition and mineralization. This measure could affect the emergence or growth of rice seedlings, thereby resulting in a reduction in effective panicle number and crop yields.

The results of the wheat yield components in 2013 (Table 4) showed that zero tillage increased the effective panicle number in wheat. The results of the ANOVA revealed that the mean effective panicle numbers of wheat were 669.49 × 104/hm2 for the RctWzt treatment group and 635.64 × 104/hm2 for the RWzt treatment group. These two values were significantly higher than that for the RWct treatment group, which was 573.70 × 104/hm2 (F = 13.705, P < 0.05). Except for the difference in effective panicle number, various tillage practices did not cause significant differences in the parameters of wheat yield components, including the grain number per panicle, 1000-grain weight, and seed setting rate. The analysis of various straw incorporation measures showed that the effective panicle number of wheat was relatively high for the treatment group with wheat straw incorporation; however, various straw incorporation rates did not present significant differences in the parameters of wheat yield components. These results indicate that zero tillage could increase the effective panicle number in wheat, which was the primary factor leading to an increase in wheat yields.

Discussion

The management measures that include tillage and straw incorporation not only determine land productivity but also affect soil microbial biomass and activity by altering the temperature and humidity of the soil, the growth stage of the roots, and the quantity and quality of the crop residues, ultimately affecting the content and stability of soil aggregates22,23,24. Figures 3 and 4 show that both the mean weight diameter (MWD) and aggregate stability (AS) of the soil aggregates were higher for the RWzt + RWsi treatment than for the RWzt + Nsi treatment. From the perspective of a farmland ecosystem, zero tillage and straw incorporation enable the topsoil to form a complex decomposition sub-system that simulates the natural ecosystem. This sub-system can buffer the impact of external force on the soil mass and gather matter and energy in the topsoil under zero tillage, where the crop roots are growing. This phenomenon of identical distributions can improve the nutrient recycling capacity and energy utilization efficiency25,26,27. However, the input of plant residues combined with zero tillage can protect the topsoil from frequent wet-dry freeze-thaw effects, thereby increasing the content of stable macroaggregates and reducing the mineralization rate of soil organic carbon28. Our results showed that the mean percentages of >2 mm macroaggregates and water-stable macroaggregates were increased by 12.77% and 43.21%, respectively, for the treatment group of rice-wheat under zero tillage compared to RWct. In the 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm soil layers, the percentage of 2–0.25 mm water-stable macroaggregates was increased by 25% and 40%, respectively, for the RWzt treatment compared to the RWct treatment. Thus, compared to conventional tillage, zero tillage can reduce the turnover of macroaggregates in farmland and facilitate the enclosure of organic carbon in microaggregates, which enables microaggregates to preserve more physically protected organic carbon and form more macroaggregates29. Moreover, our results showed that under the same tillage practice, the treatment of RWsi resulted in a 10–40% higher percentage of macroaggregates and water-stable macroaggregates relative to the treatment without straw incorporation. This result is mainly because fresh straw and other organic materials release organic substances such as polysaccharides and organic acids. These organic substances provide attachment points and nutrients for the growth of fungi and microorganisms while simultaneously promoting the cementation of straw and soil particles to form macroaggregates30. Fonte et al.31 propose that a massive input of plant residues and the avoidance of disturbance under zero tillage are the main factors underlying the improved content and stability of macroaggregates in the surface soil layer.

Regarding SOC protection by soil aggregates, the newly added carbon provides physical protection and is then subjected to chemical conversion and structural stabilization; meanwhile, alternation of the properties and distribution of the carbon pool leads to both the diversification of aggregate-scale microbial habitats and the evolution of microbial biota, along with changes in various fertility service functions such as functional groups and enzyme activity, which promote the development of diverse biota and thereby stabilize ecosystem processes. Thus, the protective mechanism of aggregates for SOC can be summarized as three interacting and interdependent processes: physical protection, chemical bonding and stabilization, and adaptation of microbial biota and functional groups32. The above results showed that zero tillage resulted in higher organic carbon storage in soil aggregates in the 0–15 cm soil layer than did conventional tillage (Figs 5 and 6), primarily because conservation tillage reduces the damage to soil aggregates and increases the content and stability of associated organic carbon accordingly. Similar findings were reported by Srinivasan et al.33 and Six et al.34, who proposed that minimum tillage results in higher SOC content in the 0–15 cm soil layer compared to conventional tillage because of the lower contents of organic carbon and water-stable aggregates in the soil under conventional tillage. Our results also showed that regardless of tillage practice, the highest SOC concentration was found for the 0.25–0.106 mm microaggregates in the 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm soil layers, which is inconsistent with the result of Six et al.15, who found that >2 mm aggregates had the highest SOC level compared to the other size classes of aggregates. Six et al.15 suggested that macroaggregates are formed by the aggregation of soil particles through cementation of organic substances and indicated that macroaggregate particles are the main carrier of organic carbon. In the present study, light-fraction organic carbon was not deducted from the aggregate components, which largely increased the SOC concentration in the 0.25–0.106 mm aggregates. Moreover, it has been suggested that microaggregates, which possess a larger specific surface area with more abundant active points, can adsorb organic substances and preserve organic carbon through strong ligand exchange and multivalent cation bridging. Consequently, the SOC levels are even higher in microaggregates than in macroaggregates35,36.

Numerous studies focusing on the influence of tillage on soil organic carbon have only considered the shallow soil layer (0–15 cm) and ignore the SOC level in the deep soil if it shows little differences or exhibits the same distribution as observed in the shallow soil37,38,39,40. In the present study, the SOC concentrations of various treatments showed inconsistent trends between the 15–30 cm and 0–15 cm soil layers. In the 0–15 cm soil layer, the RWzt treatment resulted in a higher percentage of soil aggregates than did the RWct treatment. In addition, the aggregate-associated SOC concentration was higher for RWzt. In the 15–30 cm soil layer, the percentage of soil aggregates did not show ordered differences; however, the SOC concentration was higher with conventional tillage than with conservation tillage, exhibiting the following rank: RWct > RctWzt > RWzt. This result indicates that it is necessary to consider deeper soil when assessing the influence of tillage practices on soil organic carbon. Particularly in farmland under rice-wheat rotation, different tillage practices combined with the alternating wet and dry soil environment cause quantitative changes in the soil organic carbon of deep soil. However, compared to zero tillage, conventional tillage, such as ploughing, incorporates organic materials, including straw mulch at the soil surface and residual roots in shallow soil, into deeper soil. The organic materials are tightly bound to soil particles, thereby improving the stability of their mineralization and promoting the accumulation of organic carbon in the deep soil41. This result also indicates that the analysis of organic carbon only in shallow soil will result in underestimated values. Moreover, the influence of different farmland management practices (e.g., tillage and straw incorporation) on organic carbon in the deep soil must be further investigated to appropriately estimate the carbon preservation potential of bulk soil, particularly in deep soil.

Extensive studies have shown that zero tillage can improve wheat yields42,43. However, different results have been obtained for the effect of zero tillage on rice yields, including yield improvement and yield reduction. There are different opinions about the reason for rice yield reduction. Zhuang44 suggested that zero tillage results in a higher bulk density in the 7–14 cm soil layer, which might be the primary cause of early ageing and yield reduction in rice. Feng45 reported that rice yield reductions might be attributable to the enhancement of soil permeability under zero tillage, which accelerates water percolation and fertilizer leakage, resulting in decreased rice tillering and inadequate population. In the present study, zero tillage markedly improved wheat yields. More specifically, the yield increase reached 13.32% for RctWzt compared to RWct. For rice, however, zero tillage produced a negative effect and caused a yield reduction of 10.55%. The highest crop yield of the entire wheat-rice rotation was obtained for the model of RctWzt. Combined with the above results of the aggregate-associated SOC and yield components, we conclude that zero tillage can cause nutrient enrichment in the topsoil46,47,48, increase the contents of soil aggregates and organic carbon, and thus increase the effective panicle number and improve the yield of wheat. However, tillage is not applied to paddy fields under zero tillage; thus, it is difficult to blend the soil and fertilizers. At the early growth stage of rice, substantial nutrients are lost via runoff or evaporation in the topsoil, resulting in lower levels of soil-available nutrients at the mature stage of rice, which in turn causes a shortage of fertilizers at the middle to late stage of rice. Consequently, the effective panicle number and grain number per panicle were both lower for rice under zero tillage than for rice under conventional tillage. This may be the primary cause of rice yield reductions under zero tillage. Therefore, it is recommended to grow wheat under zero tillage and rice under conventional tillage in rice-wheat cropping areas, thus achieving a high yield and saving labour.

It is indisputable that straw incorporation can improve soil fertility, reduce soil bulk density, enhance soil permeability, and increase organic carbon content in the soil49. Our results also showed that with increases in the straw incorporation rate, the soil carbon preservation capacity (CPC) was enhanced and the aggregate-associated SOC concentration was increased. However, in terms of crop yield, straw incorporation might affect wheat yields. In particular, rice-wheat straw incorporation caused a reduction in wheat yields, primarily because excess incorporated straw cannot be rapidly decomposed and mineralized. After entering the surface soil layer and mixing with the soil through conventional tillage, the large spacing among straw pieces in the topsoil causes serious soil water losses and affects seedling germination and rooting. Water shortages and straw obstacles affect the emergence rate of wheat and growth quality at the seedling stage. Consequently, wheat yields were markedly reduced under straw incorporation combined with conventional tillage. In the paddy fields, because there is an adequate water supply and a strong water retention capacity, an appropriate rate of straw incorporation will not affect the growth of rice seedlings. However, excessive straw incorporation continues to affect the effective panicle number of rice, which is unfavourable for a high yield. Additionally, the process of straw decomposition and mineralization is associated with the release of toxins, which can prevent the growth and development of crop seedlings and further affect crop yields.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that zero tillage and straw incorporation increased the contents of soil macroaggregates and organic carbon under a rice-wheat double cropping system. After three years of rice-wheat rotation, zero tillage and straw incorporation in rice-wheat double-cropping significantly increased (compared to conversion tillage) the percentage of >2 mm macroaggregates and water-stable macroaggregates and aggregate- and water stable aggregate-associated organic carbon in the soil. They also increased the mean weight diameter and stability of the soil aggregates. However, in the straw incorporation and conventional tillage treatments, straw mulch on the soil surface and residual roots from the shallow soil were incorporated by ploughing into the deep soil layer, and different forms of organic carbon occurred at higher levels in the 15–30 cm soil layer under the conventional tillage system compared to the zero tillage system. In terms of crop yield, the rice grown under the conventional tillage and the wheat grown under zero tillage showed improved equivalent rice yields of 8.77% and 6.17% compared to the rice-wheat double-cropping under zero tillage and conventional tillage, respectively. Based on the ecological and yields dual benefits, growing wheat under zero tillage and rice under conventional tillage are recommended in combination with single-crop straw incorporation in the rice-wheat cropping area.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was conducted on the Changjiang Farm (121°33′05″, 31°42′10″) in Chongming County, Shanghai, China. The study area is located in the northern subtropical zone under a typical subtropical monsoon climate. The annual average temperature is 15 °C, the annual average rainfall is 1,003.7 mm, and the annual average sunshine time is 2,104.0 hours. The frost-free period lasts approximately 229 days. The experimental soil was a waterloggogenic paddy soil. The topsoil contained organic matter, 14.0 g·kg−1; total nitrogen, 0.85 g·kg−1; alkali-hydrolysable nitrogen, 82.0 mg·kg−1; available phosphorus, 41.1 mg·kg−1; and available potassium, 118.3 mg·kg−1. The pH was 8.2 (water:soil ratio = 5:1). The cropping system under study was a rice-wheat rotation.

Experimental materials

In the experiment, rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivar Hanyou 8 was planted at a seeding rate of 185 kg·hm−2 and a row spacing of 23 cm. Wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivar Wanmai 52 was planted at a seeding rate of 120 kg·hm−2 and a row spacing of 25 cm. Straw incorporation was performed during the wheat-growing season using rice straw (C/N = 51) harvested from the experimental plots’ preceding crop, which contained 38.7% cellulose, 21.7% hemicellulose, and 19.3% lignin. Straw incorporation was performed during the rice-growing season using wheat straw (C/N = 82.74) harvested from the preceding crop, which contained 35.72% cellulose, 21.93% hemicellulose, and 18.64% lignin. Nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium fertilizers were applied as urea (N-46%), calcium superphosphate (P2O5-46%), and potassium chloride (K2O-60%), respectively.

Experimental design and field management

The experiment started in October 2010. Nine treatments were set up with different tillage practices (zero tillage and conventional plough tillage) and straw incorporation rates (Table 5).

Among these treatments, conventional tillage involved ploughing to a depth of 30 cm. There were three replicates per treatment, which were arranged using a single-factor randomized block design. Each plot was 40 m long and 6 m wide and covered an area of 240 m2. The ridges between plots and irrigation ditch ridges between blocks were wrapped and separated using plastic film. Fertilizers were applied at the following rates: N, 225 kg·hm−2; P2O5, 90 kg·hm−2; and K2O, 90 kg·hm−2 for rice; N, 270 kg·hm−2; P2O5, 60 kg·hm−2; and K2O, 90 kg·hm−2 for wheat. Straw incorporation was performed at a 100% rate (straw was pulverised into 10 cm lengths at harvest using an automatic harvester). For each crop, pulverised straw, phosphorous fertilizer, and potassium fertilizer were applied once as basal dressing before sowing. Nitrogen fertilizer was applied in two parts as basal and top dressings. The basal dressing of nitrogen fertilizer was applied at 135 and 162 kg·hm−2 for rice and wheat, respectively. The remainder of the nitrogen fertilizer was applied as a top dressing. Other field management and pest control followed local conventional practices.

Sample collection and analysis

Before the start of the experiment, basic soil samples were collected in September 2010. After the start of the experiment, rice and wheat yields were analysed in June 2011, June 2012, and June 2013 following the wheat harvest and in November 2011, November 2012, and November 2013 following the rice harvest. The soil samples were collected in November 2013. A soil auger was used to collect samples to depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm in an “S” pattern. The soil samples were immediately transported to the laboratory. Animal and plant debris, along with stones and other debris, were removed before use50. The size composition of the soil aggregates was determined by dry sieving, and the size composition of the water-stable aggregates was analysed using a DIK-2001 soil aggregate analyser (RKC instrument Inc., Saitama-ken, Japan). The aggregate-associated carbon was determined using a CHN-440 (United Instrument Co., Ltd, Chicago, USA) elemental analyser.

Data calculation and analysis

Data calculation

Where Ai% is the mass percentage of the aggregates for a certain size class, MAi is the mass of the aggregates (>2.0 mm, 2–0.25 mm, 0.25–0.106 mm, or <0.106 mm) and Ms is the mass of the air-dried soil.

Where WSAi% is the mass percentage of the water-stable aggregates for a certain size class, MWSAi is the mass of the water-stable aggregates in the size class of >2.0 mm, 2–0.25 mm, or 0.25–0.106 mm and Ms is the mass of the air-dried soil.

Where AS is the aggregate stability of the soil, n = 3, WSAMi is the mass of water-stable aggregates of >2.0 mm, 2–0.25 mm, or 0.25–0.106 mm and AMi is the mass of the aggregates of >2.0 mm, 2–0.25 mm, or 0.25–0.106 mm.

Where MWD is the mean weight diameter of the soil aggregates, n = 4, Di is the mean diameter of the soil particles in each size class (2.0 mm, 1.125 mm, 0.178 mm, or 0.53 mm) and MAi is the mass of the soil particles (>2.0 mm, 2–0.25 mm, 0.25–0.106 mm, or <0.106 mm).

Where CPC is the carbon preservation capacity of the soil aggregates, WSACi is the concentration of soil carbon in the water-stable aggregates of >2.0 mm, 2–0.25 mm, or 0.25–0.106 mm and WSAi is the percentage of water-stable aggregates of 2.0 mm, 2–0.25 mm, or 0.25–0.106 mm.

Where ERY is the equivalent rice yield, RY is the rice yield, WY is the wheat yield, RP is the government purchase price of rice for the year of the study and WP is the government purchase price of wheat for the year of the study.

Statistical analysis

The data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and then subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the SPSS 17.0 Statistical Package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Multiple comparisons of various treatments were conducted using Tukey’s method. The graphics were produced using Origin 8.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Song, K. et al. Influence of tillage practices and straw incorporation on soil aggregates, organic carbon, and crop yields in a rice-wheat rotation system. Sci. Rep. 6, 36602; doi: 10.1038/srep36602 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Brown, S. & Lugo, A. E. The storage and production of organic matter in tropical forests and their role in the global carbon cycle. Biotropica 14, 161–187 (1982).

Jarecki, M. K. & Lal, R. Crop management for soil carbon sequestration. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 22, 471–502 (2003).

Gao, H. W., Li, W. Y. & Li, H. W. Conservation tillage technology with Chinese characteristics. Trans. CSAE 19, 1–4 (2003).

Benbi, D. K. & Senapati, N. Soil aggregation and carbon and nitrogen stabilization in relation to residue and manure application in rice–wheat systems in northwest India. Nutr. Cycl Agroecosyst. 87, 233–247 (2010).

Erenstein, O. & Laxmi, V. Zero tillage impacts in India’s rice–wheat systems: a review. Soil Tillage Res. 100, 1–14 (2008).

Miura, T., Kaneko, N. & Komatsuzaki, M. [Earthworm contributes to supply available phosphorus in agricultural soil with no-tillage, weed-cover and low-input management. A case study of nature farming in Ibaraki Prefecture]. Org. Agric. Sci. 2, 30–39 (2010).

Bajracharya, R. M., Lal, R. & Kimble, J. M. Soil organic carbon distribution in aggregates and primary particle fractions as influenced by erosion phases and landscape position in Soil processes and the carbon cycle (ed. Lal, R., Kimble, J. M., Follett, R. F. & Stewart, B. A. ) 353–367 (CRC Press, 1997).

Koga, N. & Tsuji, H. Effects of reduced tillage, crop residue management and manure application practices on crop yields and soil carbon sequestration on an Andisol in northern Japan. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 55, 546–557 (2009).

Oades, J. M. Soil organic matter and structural stability: mechanisms and implications for management. Plant Soil 76, 319–337 (1984).

Muramoto, J. & Werner, M. R. Mustard powder vermifuge: an alternative to formalin expulsion method for earthworm sampling. Edaphologia 70, 7–11 (2002).

Paterson, E. Importance of rhizodeposition in the coupling of plant and microbial productivity. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 54, 741–750 (2003).

Carter, M. R. Soil quality for sustainable land management: organic matter and aggregation interactions that maintain soil functions. Agron. J. 94, 38–47 (2002).

Blanco-Canqui, H., Schlegel, A. J. & Heer, W. F. Soil-profile distribution of carbon and associated properties in no-till along a precipitation gradient in the central Great Plains. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 144, 107–116 (2011).

Fonte, S. J., Winsome, T. & Six, J. Earthworm populations in relation to soil organic matter dynamics and management in California tomato cropping systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 41, 206–214 (2009).

Six, J., Elliott, E. T. & Paustian, K. Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: a mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32, 2099–2103 (2000).

Li, X., Wang, Z., Ma, Q. & Li, F. Crop cultivation and intensive grazing affect organic C pools and aggregate stability in arid grassland soil. Soil Tillage Res. 95, 172–181 (2007).

Holland, J. M. The environmental consequences of adopting conservation tillage in Europe: reviewing the evidence. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 103, 1–25 (2004).

Choudhury, G. S., Bandyopadhyay, P. K., Mallick, S. & Sarkar, S. Soil aggregation as affected by cultivation under low and dryland situations. J. Ind. Soc. Soil Sci. 58, 371–375 (2010).

West, T. A. & Post, W. M. Soil organic carbon sequestration rates by tillage and crop rotation: a global data analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 66, 1903–1946 (2002).

Rudrappa, L., Purakayastha, T. J., Singh, D. & Bhadraray, S. Long-term manuring and fertilization effects on soil organic carbon pools in a typic Haplustept of semi-arid sub-tropical India. Soil Tillage Res. 88, 180–192 (2006).

Campbell, C. A., Selles, F., Lafond, G. P., Biederbeck, V. O. & Zentner, R. P. Tillage - fertilizer changes: effect on some soil quality attributes under long-term crop rotations in a thin Black chernozem. Can. J. Soil Sci. 81, 157–165 (2001).

Curaqueo, G. et al. Effects of different tillage system on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal propagules and physical properties in a Mediterranean agroecosystem in central Chile. Soil Tillage Res. 113, 11–18 (2011).

Ramachandran Nair, P. K., Mohan Kumar, B. & Nair, V. D. Agroforestry as a strategy for carbon sequestration. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 172, 10–23 (2009).

Zhang, S. et al. Effects of conservation tillage on soil aggregation and aggregate binding agents in black soil of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 124, 196–202 (2012).

Lorenz, K., Lal, R. & Donald, L. S. The depth distribution of soil organic carbon in relation to land use and management and the potential of carbon sequestration in subsoil horizons. Adv. Agron. 88, 35–66 (2005).

Husnjak, S., Filipovic, D. & Kosutic, S. Influence of different tillage systems on soil physical properties and crop yield. Rostlinna Vyroba 48, 249–254 (2002).

Aoyama, M., Angers, D. A. & N’Dayegamiye, A. Particulate and mineral-associated organic matter in water-stable aggregates as affected by mineral fertilizer and manure applications. Can. J. Soil Sci. 79, 295–302 (1999).

Bandyopadhyay, P. K., Saha, S., Mani, P. K. & Mandal, B. Effect of organic inputs on aggregate associated organic carbon concentration under long-term rice–wheat cropping system. Geoderma 154, 379–386 (2010).

Causarano, H. J. et al. Soil organic carbon fractions and aggregation in the Southern Piedmont and Coastal Plain. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 72, 221–230 (2008).

Decaëns, T. Degradation dynamics of surface earthworm casts in grasslands of the eastern plains of Colombia. Biol. Fertil. Soils 32, 149–156 (2000).

Fonte, S. J., Quintero, D. C., Velásquez, E. & Lavelle, P. Interactive effects of plants and earthworms on the physical stabilization of soil organic matter in aggregates. Plant Soil 359, 205–214 (2012).

Haile, S. G., Nair, P. K. R. & Nair, V. D. Carbon storage of different soil-size fractions in Florida silvopastoral systems. Environ. Qual. 37, 1789–1797 (2008).

Srinivasan, V., Maheswarappa, H. P. & Lal, R. Long term effects of topsoil depth and amendments on particulate and non particulate carbon fractions in a Miamian soil of Central Ohio. Soil Tillage Res. 121, 10–17 (2012).

Six, J., Conant, R. T., Paul, E. A. & Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant Soil 241, 155–176 (2002).

Razafimbelo, T. M. et al. Aggregate associated-C and physical protection in a tropical clayey soil under Malagasy conventional and no-tillage systems. Soil Tillage Res. 98, 140–149 (2008).

Álvaro-Fuentes, J., Arrúe, J. L., Gracia, R. & López, M. V. Tillage and cropping intensification effects on soil aggregation: temporal dynamics and controlling factors under semiarid conditions. Geoderma 145, 390–396 (2008).

Arai, M. et al. Changes in soil aggregate carbon dynamics under no-tillage with respect to earthworm biomass revealed by radiocarbon analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 126, 42–49 (2013).

De Deyn, G. B. et al. Additional carbon sequestration benefits of grassland diversity restoration. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 600–608 (2011).

Zhang, X. H., Li, L. Q. & Pan, G. X. Effect of different crop rotation systems on the aggregates and their SOC accumulation in Paludalfs in North Huai region. Chin. J. Ecol. 20, 16–19 (2001).

Spohn, M. & Giani, L. Impacts of land use change on soil aggregation and aggregate stabilizing compounds as dependent on time. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43, 1081–1088 (2011).

Pinheiro, E. F. M., Pereira, M. G. & Anjos, L. H. C. Aggregate distribution and soil organic matter under different tillage systems for vegetable crops in a red latosol from Brazil. Soil Tillage Res. 77, 79–84 (2004).

Changquan, W., Chengming, W. & Tingaiang, L. Effect of different zero tillage on the crop yield and soil property. J. Sichuan Agricult. Univ. 19, 152–155 (2001).

Lithourgidis, A. S., Dhima, K. V., Damalas, C. A., Vasilakoglou, I. B. & Eleftherohorinos, I. G. Tillage effects on wheat emergence and yield at varying seeding rates, and on labor and fuel consumption. Crop Sci. 46, 1187–1192 (2006).

Zhang, H. Y., Li, S. P. & Shen, X. P. [Effect of long: term minimal and zero tillages on rice-wheat yields, soil organic matter and bulk density]. Sci. Agricult. Sin. 32, 39–44 (1999).

Feng, Y. H., Zou, Y. B. & Roland, J. Effects of no-tillage and direct broadcasting on soil physical and chemical properties and growth and yield formation in hybrid rice. Acta Agron. Sin. 32, 1728–1736 (2006).

Gangwar, K. S., Singh, K. K. & Sharma, S. K. Effect of tillage on growth, yield and nutrient uptake in wheat after rice in the Indo-gangetic plains of India. J. Agric. Sci. 142, 453–459 (2004).

Li, H., Lu, W., Liu, Y. & Zhang, X. [Effect of different tillage methods on rice growth and soil ecology]. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 12, 553–556 (2001).

Shumin, L. et al. Effects of tillage systems on fields in chengdu plain. I. The effects of tillage systems on soil properties and crop yields. Sci. Agricult. Sin. 43, 3988–3996 (2010).

Shreyasi, G. C. et al. Tillage and residue management effects on soil aggregation, organic carbon dynamics and yield attribute in rice–wheat cropping system under reclaimed sodic soil. Soil Till. Res. 136, 76–83 (2013).

Lu, R. K. Agronomical and chemical analysis of soil [in Chinese] (Agriculture Press, 2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues at the Institute of Eco-Environment and Plant Protection, Shanghai Academy of Agricultural Sciences for their assistance with sample collection and analysis. This work was supported by the Growth of Youth Talents Program of Shanghai Municipal Agricultural Commission (Shanghai Agricultural Youth (2015) No. 1–22), the 1:50,000 Soil Map Compilation and High-Precision Digital Soil Construction Project of China (2012FY112100), and the Study on Key Technologies for Regulation of Straw Incorporation and Rapid Improvement of Farmland Productivity (12230707100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ke Song and Jianjun Pan designed the study; Ke Song and Xianqing Zheng performed the experiments; Ke Song wrote the manuscript. Jianjun Yang, Weiguang Lv and Yong Xue reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Song, K., Yang, J., Xue, Y. et al. Influence of tillage practices and straw incorporation on soil aggregates, organic carbon, and crop yields in a rice-wheat rotation system. Sci Rep 6, 36602 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36602

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36602

This article is cited by

-

Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation in rice agriculture

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Climate and soil management factors control spatio-temporal variation of soil nutrients and soil organic matter in the farmland of Jiangxi Province in South China

Journal of Soils and Sediments (2023)

-

Tillage and Residue Management Impact on Microbial and Nematode Abundance Under Diverse Rice-Based Cropping Systems in Calcareous and Non-calcareous Floodplain Soils

Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition (2023)

-

Different tillage and stubble management practices affect root growth and wheat production in a semi-arid area

Plant and Soil (2023)

-

Organic amendments and conservation tillage improve cotton productivity and soil health indices under arid climate

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.