Abstract

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation by bacterial infection, or by sterile inflammatory insult is a primary trigger of spontaneous preterm birth. Here we utilize mouse models to investigate the efficacy of a novel small molecule TLR4 antagonist, (+)-naloxone, the non-opioid isomer of the opioid receptor antagonist (−)-naloxone, in infection-associated preterm birth. Treatment with (+)-naloxone prevented preterm delivery and alleviated fetal demise in utero elicited by i.p. LPS administration in late gestation. A similar effect with protection from preterm birth and perinatal death, and partial correction of reduced birth weight and postnatal mortality, was conferred by (+)-naloxone administration after intrauterine administration of heat-killed E. coli. Local induction by E. coli of inflammatory cytokine genes Il1b, Il6, Tnf and Il10 in fetal membranes was suppressed by (+)-naloxone, and cytokine expression in the placenta, and uterine myometrium and decidua, was also attenuated. These data demonstrate that inhibition of TLR4 signaling with the novel TLR4 antagonist (+)-naloxone can suppress the inflammatory cascade of preterm parturition, to prevent preterm birth and perinatal death. Further studies are warranted to investigate the utility of small molecule inhibition of TLR-driven inflammation as a component of strategies for fetal protection and delaying preterm birth in the clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preterm birth, defined as birth at less than 37 weeks of gestation, accounts for 12% of all births worldwide,varying from 5–13% according to geographic region, race and socioeconomic status1,2. The cost to infant health is enormous, particularly in undeveloped nations where the majority of spontaneous premature birth occurs3. Preterm birth is now the major cause of death in children under 5 years, accounting for 1.1 million deaths annually4, while surviving infants are at risk of a raft of developmental impairments with lifelong consequences5,6. Even late preterm infants born at 34–36 weeks gestation have substantial mortality and neonatal morbidity, and have elevated risk of long-term cardiovascular and metabolic conditions5,7. New interventions are urgently needed to tackle the underlying causes of preterm birth and stem the impact on fetal injury and ensuing child health8.

Preterm delivery (PTD) results when the labour and birth processes of normal parturition are prematurely activated. On-time, term labour involves events characteristic of a progressively accelerating inflammatory cascade9. Fetal signals trigger a surge in pro-inflammatory cytokines including Il1b, Il6 and Tnf within the fetal membranes, uterus and cervix and an accompanying influx of leukocytes into the gestational tissues10,11 amplifies the inflammatory sequalae to promote cervical ripening and rupture of the fetal membranes12,13. Cytokines interact with hormone changes to mediate induction of uterine activation genes (UAGs) and prostaglandin signaling, culminating in uterine contractions and expulsion of the fetus14,15.

Precocious inflammation leading to preterm labor can be triggered by infection or by sterile pro-inflammatory insults, originating either within gestational tissues or systemically, from tissues distal to the placenta and fetus1,16. Detection of infection is mediated by sensing molecules known as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) that bind conserved molecular structures carried by microorganisms, known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). TLRs also sense silent inflammation resulting from non-infectious insult, through ligation of endogenous agents released by injured tissue (damage-associated molecular patterns, DAMPs). The archetypal receptor in this detection system is TLR4, which is activated by the bacterial cell wall component lipopolysaccharide (LPS). TLR4 is extensively expressed throughout the female reproductive tract including the fetal membranes17,18 and placental trophoblasts19,20, as well as leukocytes, epithelial and mesenchymal cells in the cervix20 and uterus21. TLR-driven pathways are involved in normal on-time parturition, since mice with null mutation in Tlr4 or Tlr2 exhibit a delay in the timing of term labour22,23.

Infection-induced preterm labor can be modelled in mice by administration of LPS systemically or locally into the gestational tissues24,25,26, or delivery of killed E. coli into the uterine cavity or fetal membranes to mimic ascending infection and chorioamnionitis27,28. TLR4 is a key sensor for infection-induced preterm birth, since protection is afforded in mice by spontaneous mutation of Tlr4 in C3H/HeJ mice27,29,30, null mutation of Tlr4 in C57Bl/6 mice22,30, and genetic deficiency in the MyD88 and TRIF adaptor proteins required for TLR4 signaling28. TLR4 inhibitors including a lipid A mimetic and anti-TLR4 neutralising antibodies have previously shown promise in attenuating preterm birth in mouse infection models24,30, but neither of these are suitable for human clinical application.

These observations underpin our hypothesis that TLR4 inhibition with a novel TLR4 antagonist (+)-naloxone might comprise a useful strategy for targeted suppression of inflammation underlying preterm birth. (+)-Naloxone is a newly identified TLR4 antagonist that is the non-opioid isomer of the opioid receptor antagonist (−)-naloxone31, a well-described nonselective antagonist of the μ-opioid receptor commonly prescribed for opioid addiction, including in pregnant women and neonates32. (+)-Naloxone binds MD2 to prevent LPS engagement with TLR433 leading to diminished immune NFκB activation and IL1B, IL6 and TNF synthesis34,35,36. In contrast to anti-TLR4 neutralizing antibodies24, (+)-naloxone is a small molecule which can penetrate across the placenta37, with a pharmacokinetic profile affording it short systemic exposure or longer term delivery if required. (−)-Naloxone has anti-inflammatory activity and provides protection against sepsis in animal models38,39. (+)-Naloxone has similar properties but unlike (−)-naloxone, does not have opioid receptor-binding activity, and is a specific antagonist of TLR4 signaling31.

In view of the attractive pharmacological properties of (+)-naloxone as a TLR4 antagonist and our previous observation that (+)-naloxone can delay the timing of natural on-time parturition22, we sought to investigate the possible utility of (+)-naloxone as a novel anti-inflammatory tocolytic agent. Here, we use two common mouse models of infection-induced preterm birth to show (+)-naloxone protects against preterm delivery and alleviates in utero and postnatal loss induced by TLR-driven inflammation.

Results

(+)-Naloxone prevents LPS-induced preterm delivery (PTD)

To investigate the effect of (+)-naloxone in a TLR4-dependent model of infection-associated preterm birth, pregnant B6 dams were administered a low dose of LPS (0.5 μg i.p.), selected after titration of LPS in pilot studies to elicit ~50% PTD, as previously described40,41. LPS was administered at gestation day (gd) 16.5 (~3 days before expected on-time birth at gd 19.5), followed immediately by the first of 4 doses of (+)-naloxone or vehicle control at 12 h intervals until gd 18.0. Mice given LPS without (+)-naloxone exhibited adverse outcomes, with a majority delivering dead pups (9/20) or live pups (2/20) prematurely within 36 h (and generally within 24 h) of LPS administration (Fig. 1A). Those few pups delivered alive before gd 18.0 failed to survive beyond 36 h. In all, PTD (defined as delivery of live or dead pups before gd 18.0) occurred in 55% (11/20) LPS-treated, but 0% (0/15) PBS-treated mice (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). In the 45% (9/20) LPS-treated dams remaining undelivered at gd 18.5, autopsy revealed a higher incidence of severe fetal growth restriction and fetal death (18.9%, 10/53) compared to PBS-treated controls (1/115, 0.8%, p = 0.023) (Fig. 1C,D). Taking into account pups delivered dead or identified as non-viable in utero, there was a 58% reduction in the mean number of viable fetuses per pregnant dam, compared with PBS-treated mice (Fig. 1E).

(+)-Naloxone prevents LPS-induced PTD and fetal loss.

Pregnant B6 mice were administered LPS or PBS i.p. on gd 16.5, followed by (+)-naloxone or PBS i.p. on gd 16.5, 17.0, 17.5 and 18.0, then observed for PTD (delivered gd < 18.0) and autopsied at gd 18.5. (A) Dam outcomes at gd 18.5, classified as (i) pregnant (>1 live fetus); (ii) delivered early (gd 18.0–18.5); delivered preterm (gd < 18.0; >1 live pup), or (iv) delivered preterm, all pups dead. (B) The percentage of pregnant dams exhibiting PTD. (C) Fetuses and placentae dissected from a representative dam in each treatment group. Pups marked ‘*’ are judged non-viable. (D) Fetal outcomes at gd 18.5, classified as (i) resorbed; (ii) viable, in utero; (iii) viable, delivered preterm; (iv) non-viable, in utero, or (v) dead, delivered preterm. All pups born alive before gd 18.0 were dead within 36 h. (E) The number of viable pups per dam. Data in (A,B,D) are percentage analyzed by χ2 test. Data in (E) are mean ± SEM analysed by two-way ANOVA. Number of pregnant dams per group is shown in parentheses. a,b,cDifferent letters indicate differences between groups, p < 0.05.

Treatment with (+)-naloxone protected pregnancy from LPS challenge, completely abrogating PTD (0/14 mice delivered before gd 18.0) (Fig. 1A,B). The low survival rate of fetuses in utero after LPS challenge was also reversed by (+)-naloxone, such that the mean number of viable fetuses per dam was not less than the control PBS-treated group (Fig. 1C–E). Moreover, administration of (+)-naloxone alone in the absence of LPS did not induce PTD (0/14 mice) or affect fetal survival rates (Fig. 1A–E).

When fetuses surviving in utero at gd 18.5 were analysed for effects of treatments on fetal and placental weight, mixed model ANOVA showed that LPS reduced fetal weight (p = 0.033) (Fig. 2A) and elevated placental weight (p = 0.019) (Fig. 2B), causing a substantial reduction in fetal:placental weight ratio (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2C), a parameter indicative of placental functional efficiency. Conversely (+)-naloxone exerted a positive impact on fetal weight (p = 0.045), and did not affect placental weight or fetal:placental weight ratio. Post-hoc analysis to compare individual treatment groups demonstrated a 15.2% reduction in fetal:placental weight ratio after LPS treatment compared to PBS control (p = 0.036) (Fig. 2C), but (+)-naloxone treatment was not able to correct this.

Effects of LPS and (+)-naloxone on fetal and placental weight.

Pregnant B6 mice were administered LPS or PBS i.p. on gd 16.5, followed by (+)-naloxone or PBS i.p. on gd 16.5, 17.0, 17.5 and 18.0, then fetal weight, placental weight and fetal:placental weight ratio were measured at gd 18.5. (A) Fetal weight; (B) placental weight, and (C) fetal:placental weight ratio for surviving fetuses. Data are estimated marginal mean ± SEM, analyzed by Mixed Model Linear Repeated Measures ANOVA and post-hoc LSD t-test, with mother as the subject, adjusted for litter size. a,b,cDifferent letters indicate differences between groups, p < 0.05. *Significant effect of LPS, independent of (+)-naloxone, p < 0.05. #Significant effect of (+)-naloxone, independent of LPS, p < 0.05. Number of pregnant dams per group is shown in parentheses.

These data indicate that (+)-naloxone can effectively inhibit TLR4 signaling to prevent PTD and rescue fetal loss elicited by LPS administration in late gestation. However, fetuses that survive LPS challenge in utero exhibited altered placental efficiency indicated by reduced fetal:placental weight ratio, regardless of (+)-naloxone treatment.

(+)-Naloxone prevents heat-killed E. coli-induced preterm delivery

Given the ability of (+)-naloxone to prevent LPS-induced PTD, we next investigated whether (+)-naloxone can also prevent PTD induced by intact bacteria, which elicit PTD by ligation of multiple TLRs including TLR4 and TLR242,43. In this experiment, we used a proven model of chorioamnionitis-induced PTD wherein heat-killed E. coli are surgically instilled into the uterine cavity between gestation sacs27,28. The dose of heat-killed E. coli was selected to elicit ~50% PTD after titration of E. coli in pilot studies. After E. coli administration on gd 16.5, mice were monitored for time of delivery and the survival of pups. Instillation of killed E. coli into the uterus on gd 16.5 caused PTD in 70% (7/10) of treated mice (Fig. 3A), with an associated 36 h average reduction in gestation length (Fig. 3B) and 66% reduction in viable litter size at birth (Fig. 3C). The timing of birth and live birth rate were substantially rescued by (+)-naloxone treatment, with none of 10 mice delivering before gd 18.0, a comparable gestation length, and no change in mean number of viable pups born compared to PBS control (Fig. 3A–C). Again, (+)-naloxone alone had no impact on timing of birth or litter size (Fig. 3A–C).

(+)-Naloxone prevents E. coli-induced PTD and fetal loss.

Pregnant B6 mice were administered intrauterine heat-killed E. coli or PBS on gd 16.5, followed by (+)-naloxone or PBS i.p. on gd 16.5, 17.0, 17.5 and 18.0, then observed for PTD and allowed to progress to birth. (A) The percentage of pregnant dams exhibiting PTD, analyzed by χ2 test. (B) The gestation length, (C) number of viable pups born per dam, (D) pup weight at 24 h, (E) pup survival to 3 weeks and (F) weight of surviving pups at 3 weeks. (B,C,E) Data are mean ± SEM analyzed by two-way ANOVA, and (D,F) data are estimated marginal mean ± SEM, analysed by Mixed Model Linear Repeated Measures ANOVA and post-hoc LSD t-test, with mother as the subject. a,b,cDifferent letters indicate differences between groups, p < 0.05. *Significant effect of E. coli, independently of (+)-naloxone, p < 0.001. Number of pregnant dams per group is shown in parentheses.

When surviving delivered pups were analysed for effects of treatments at 12–24 h after birth, mixed model ANOVA showed E. coli administration had a strong negative impact on pup birth weight (p < 0.001). (+)-Naloxone did not affect birth weight independently, but a significant interaction with E. coli was present (p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that co-administration of (+)-naloxone alleviated the reduction in birth weight caused by E. coli treatment, such that the pups born after exposure in utero to both (+)-naloxone and E. coli were not different in weight to pups of PBS-treated control dams (Fig. 3D).

The majority of pups born small were lost in the post-natal and pre-weaning period, with only 13% of pups born alive from dams administered E. coli surviving to 3 weeks of age, compared to 90% and 88% respectively of pups from dams given PBS or (+)-naloxone controls. Co-administration of (+)-naloxone rescued the majority of pups with 56% surviving to 3 weeks of age (Fig. 3E), at which time their growth was comparable to those of the control groups (Fig. 3F).

This experiment demonstrates the utility of the TLR4 antagonist (+)-naloxone in preventing prematurity and perinatal death, and alleviating fetal and postnatal growth impairment, in a physiologically relevant model of preterm birth and in utero inflammation.

(+)-Naloxone abrogates fetal and uterine cytokine expression induced by heat-killed E. coli

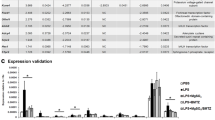

E. coli-induced preterm birth is elicited when ligation of TLRs activates an inflammatory cascade, initiated when activation of NFκB triggers expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines Il1b, Il6 and Tnf in the fetal membranes and other gestational tissues22,28,44. In turn, cytokines induce uterine activation genes to cause prostaglandin synthesis and signaling, cervical ripening and uterine contractions15,45. To examine the mechanisms underlying the protective action of (+)-naloxone, we evaluated whether pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by intrauterine instillation of E. coli are influenced by (+)-naloxone administration. The placenta and fetal membranes, as well as maternal decidua and myometrium were collected from the two fetal units located immediately adjacent to the injection site, 4 h after E. coli administration with or without (+)-naloxone treatment, as before. In the fetal membranes and placenta, the sites of earliest response to TLR ligation to trigger the labor cascade22, E. coli induced a 9.1-fold and 2.1-fold increase in Il1a expression, a 62-fold and 6.3-fold increase in Il1b, a 33-fold and 3.3-fold increase in Il6, a 131-fold and 3.7-fold increase in Tnf, and 95-fold and 4.3-fold increase in Il10, compared to tissues from control mice given PBS (Fig. 4A–J). Administration of (+)-naloxone substantially reduced E. coli-driven cytokine expression particularly in fetal membranes, meeting statistical significance for Il1b, Il6, Tnf and Il10, which were reduced by 78%, 84%, 66% and 73% respectively (Fig. 4G–J).

(+)-Naloxone suppresses E. coli–induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in placenta and fetal membranes.

Pregnant B6 mice were administered intrauterine heat-killed E. coli or PBS on gd 16.5, followed by (+)-naloxone or PBS i.p., and 4 hours later, placenta and fetal membranes were recovered from the two adjacent implantation sites. Relative expression of Il1a (A,F), Il1b (B,G), Il6 (C,H), Tnf (D,I) and Il10 (E,J) mRNAs were determined in placenta (A–E) and fetal membranes (F–J) by qPCR and normalised to Actb. Data are mean ± SEM relative gene expression of n = 12 tissues from n = 6 dams/group and were analysed by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Sidak t-test. a,b,cDifferent letters indicate differences between groups, p < 0.05.

In the maternal tissues of the uterine decidua and myometrium, which are more spatially distant from the injection site, E. coli elicited increases in some of the same pro-inflammatory cytokines, although to a lesser extent than in fetal tissues (Fig. 5A–L). (+)-Naloxone given with E. coli challenge reduced decidual expression of Il1a by 62% (Fig. 5G), and reduced Tnf in both the myometrium and decidua by 43% and 45% respectively (Fig. 5D–J). Most uterine activation genes (Gja1, Oxtr, Ptger4, Ptgfr and Ptgs1; data not shown) were not elevated by E. coli treatment, likely because of the short 4 h time window between treatment and tissue analysis. However, Ptgs2 encoding prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (cyclooxygenase-2, Cox2) was increased in response to E. coli challenge in both the myometrium (12.1-fold, Fig. 5F) and decidua (7.0-fold, Fig. 5L) compared to control. A trend towards decreased Ptgs2 after (+)-naloxone treatment in E. coli challenged mice did not reach statistical significance in either tissue (Fig. 5F,L). (+)-Naloxone administered without E. coli had no impact on gene expression in any of the fetal or maternal tissues (Figs 4 and 5).

(+)-Naloxone suppresses E. coli–induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in uterine decidua and myometrium.

Pregnant B6 mice were administered intrauterine heat-killed E. coli or PBS on gd 16.5, followed by (+)-naloxone or PBS i.p., and 4 hours later, uterine decidua and myometrium were recovered from the two adjacent implantation sites. Relative expression of Il1a (A,G), Il1b (B,H), Il6 (C,I), Tnf (D,J), Il10 (E,K) and Ptgs2 (F,L) mRNAs were determined in placenta (A–F) and fetal membranes (G–L) by qPCR and normalised to Actb. Data are mean ± SEM relative gene expression of n = 12 tissues from ne = 6 dams/group and were analysed by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Sidak t-test. a,b,cDifferent letters indicate differences between groups, p < 0.05.

These data show that the surge in pro-inflammatory cytokines released from fetal tissues contacting killed E. coli to trigger PTD, is suppressed by (+)-naloxone. This is consistent with an action of (+)-naloxone in preventing TLR4 ligation to trigger initiation of the inflammatory cascade that ultimately leads to preterm birth.

Discussion

Normal on-time delivery is an inflammatory process that involves release of endogenous TLR ligands from the maturing fetus to ligate TLRs in fetal membranes and placental tissue22,23,46. Preterm delivery results when infection and/or sterile inflammatory agents cause pathogen-derived or endogenous TLR ligands to prematurely activate the TLR-induced inflammatory cascade8,26. Here we demonstrate that administration of a novel small molecule TLR4 antagonist (+)-naloxone is an effective treatment to suppress PTD and associated perinatal death induced in mice by systemic LPS or intrauterine administration of heat-killed E. coli. Gene expression analysis reveals that (+)-naloxone treatment inhibits E. coli-induced progression of the labor cascade by inhibiting induction in fetal membranes of pro-inflammatory cytokines Il1a, Il1b, Il6 and Tnf, which are identified as responsible for the amplification of inflammation and eventual maturation of the myometrium to overcome quiescence, induce cervical ripening, activate uterine contraction and expel the fetus41,47. All dams that received four doses of (+)-naloxone at 12 h intervals, effectively encompassing the window between inflammatory challenge and earliest gestational age compatible with post-delivery survival in mice, delivered on time with the expected number of pups. The majority of pups survived the perinatal period and developed normally to 3 weeks of age. This demonstrates that (+)-naloxone protection of fetuses from TLR4-driven inflammation in late gestation is consistent with normal birth, postnatal survival and development of offspring at least to weaning age.

Exposure to TLR4-induced inflammation impacted fetal growth in late gestation, in association with evidence of reduced placental transport function, as described in previous studies40,48. Although no protective effect on mean fetal weight in viable fetuses was discernible at gd 18.5, fetuses at this time had been exposed to a pro-inflammatory environment for just 48 h, and effects on growth were less evident than in the E. coli model where birth weights were examined. Reduced birth weight was evident in pups exposed in utero to E. coli, and this was at least partly reversed by (+)-naloxone treatment.

TLR4 is present in many compartments of the gestational tissues and reproductive tract and is well-positioned as a key sensing system and rapid first-line response to ascending or systemic bacterial infection. Fetal membrane TLR4 expression appears of paramount importance as the membranes comprise the site of earliest response to endogenous TLR ligation to trigger term labor22. The highest fold-change expression in inflammatory cytokines induced by E. coli was seen in this tissue as opposed to placental or uterine tissues, and additionally cytokine suppression by (+)-naloxone was most profound in this compartment.

Mouse models of preterm birth often report heterogeneous effects amongst dams including preterm delivery of dead and live pups, and/or fetal injury or death in utero without delivery48,49. In the current study most dams delivered dead pups within 36 h of LPS or E. coli administration. With this outcome it is not obvious whether fetal death occurs in utero or in the perinatal phase, and thus whether death is the cause or consequence of early delivery. However, the observation of fetal death in utero in several dams, 48 h after LPS administration at gd 18.5, is consistent with the view that fetal injury and death can occur in situ after inflammatory challenge, independently of early delivery. Likewise, birth of live pups in a small proportion of preterm deliveries suggests fetal death is not essential for premature activation of the maternal parturition response. Consistent with previous reports48, we found that live pups born before gd 18.0 died soon after birth, presumably due to a combination of developmental immaturity and inflammatory injury inflicted in utero. These observations are consistent with interacting but distinct causal pathways underpinning the effects of inflammatory triggers on fetal and maternal tissue compartments.

Suppression of TLR4-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in gestational tissues is inferred to be the key mechanism underlying the failure of bacterial agent-induced inflammation to progress to premature labor in mice given (+)-naloxone, in turn protecting mice from subsequent late gestation or perinatal death of fetuses. Our data using both LPS and heat-killed E. coli to induce preterm delivery are consistent with previous studies employing these models27,28, where elevated IL1B, IL6 and TNF signaling are implicated in progressing both the uterine maturation and injury to fetal tissues that ultimately results in preterm birth and fetal death respectively.

Administration of (+)-naloxone to mice given E. coli substantially suppressed cytokine expression, particularly in fetal membranes and variably in placenta, the tissues most proximal to E. coli deposition between fetal sacs. This demonstrates that inhibition of TLR4 signaling in these tissues can prevent the progression of the inflammatory cascade that culminates in preterm birth and fetal death. It is notable that (+)-naloxone is efficacious despite the fact that E. coli activates inflammation by activation of TLRs in addition to TLR4, including TLR242,43. Different TLRs can trigger different cellular responses in gestational tissues, for example in placental trophoblasts where TLR4 ligation induces cytokine expression whereas TLR2 predominantly leads to apoptosis19. This presumably affects placental function and fetal growth, thus explaining why despite robust protection from preterm birth and perinatal death, (+)-naloxone was only partially effective in mitigating fetal growth impairment and protecting growth restricted pups from death in the postnatal phase following E. coli treatment in utero. Although (+)-naloxone is a small molecule that is able to penetrate the placental barrier37, it is possible that (+)-naloxone accesses the maternal and fetal compartments to differing extents, perhaps reaching higher and more effective concentrations in maternal tissues than in fetal tissues. Further experiments are required to investigate this, as well as to evaluate how (+)-naloxone affects cervical ripening, another important aspect of the parturition cascade.

In addition to pro-inflammatory genes, we examined effects of E. coli and (+)-naloxone on expression of UAGs. Induction of UAGs is secondary to hormone changes and pro-inflammatory cytokine upregulation15 so given the short time frame of the gene expression experiment, it is unsurprising that most UAGs were not elevated 4 h following E. coli administration. Expression of Ptgs2 which controls PGE2 synthesis was elevated 4 h after E. coli administration, and a trend to suppression in its expression was evident with (+)-naloxone treatment. (+)-Naloxone has previously been shown to reduce LPS-induced TLR4-mediated Ptgs2 and PGE2 synthesis in mouse macrophages36. PGE2 is a key factor in the prostaglandin signaling pathway required for cervical ripening and parturition50. Sustained delivery of (+)-naloxone beyond a single dose may be required to achieve greater Ptgs2 suppression.

Previous studies support the notion of targeting TLR4 to prevent infection-associated preterm birth. Blockade of TLR4 signaling with anti-TLR4 monoclonal antibody reduces leukocyte activation and the incidence of preterm labor induced by LPS24. In mice given Fusobacterium nucleatum, a gram negative bacteria associated with preterm birth and premature rupture of membranes in women51, administration of a TLR4 antagonist lipid A mimetic CXR-526 acted to reduce fetal loss30. CXR-526 did not suppress bacterial colonization of the placenta, but did reduce the extent of necrosis within placental tissue30. The authors concluded that decreased placental necrosis might reflect TLR4 antagonist-mediated suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, as reported previously for CXR-526 in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease52, but cytokines were not directly investigated in that study.

Other studies identify downstream agents of TLR4-driven inflammation as additional effective targets for inhibiting infection-induced preterm birth53. Experiments in null mutant mice implicate IL1 and IL6, cytokines induced by TLR4 activation of NFκB, in amplifying and accelerating the birth cascade41,47, while anti-inflammatory IL10 suppresses IL1 and IL6 production and protects against LPS-induced preterm birth48,54. As well as cytokines, immune regulators that attenuate TLR-mediated inflammation can impact susceptibility to LPS-induced preterm birth. For example, the cannabinoid receptor Cnr2 modulates dendritic cell production of IL10 and IL6, such that mice genetically deficient in Cnr2 are resistant to LPS-induced preterm birth55. Prostaglandins synthesized after Ptgs2 induction by LPS administration contribute to cervical ripening and other endpoints of parturition, and suppression of Ptgs2 with specific inhibitors can modulate LPS-induced PTD rate56. Pretreatment with rosiglitazone, which promotes placental synthesis of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) similarly attenuates responsiveness to LPS-induced PTD, in association with suppressed NFκB signaling and reduced synthesis of TNF, IL1, IL6 and other pro-inflammatory chemokines57. Thus the current study adds to considerable evidence that TLR-driven inflammatory signaling can be attenuated to effectively reduce susceptibility to preterm birth.

TLR4 is an attractive drug target in preterm birth because of its role at the apex of the inflammatory pathway. (+)-Naloxone and related drug compounds have potential benefits over neutralising antibodies and other TLR4 antagonists. (+)-Naloxone potently blocks LPS-induced TLR4-mediated signaling in a variety of non-pregnancy models, suppressing NFκB activation and inhibiting TNF and IL1B induction in immune cells34,35. As well as capacity to access and cross the placental barrier37, the established safety profile of closely related (−)-naloxone in pregnancy and infants is encouraging. In humans, (−)-naloxone is approved for use in pregnancy and no negative neonatal outcomes are reported58,59. Given the lack of opioid receptor activity of (+)-naloxone owing to the stereo-selectivity of opioid receptors33, (+)-naloxone has distinct advantages over the currently available (−)-naloxone by virtue of its inability to alter endogenous opioid signaling, which in a clinical setting would afford freedom to employ exogenous opioids for maternal pain relief in labor.

Together, these results indicate that (+)-naloxone is a useful experimental drug for investigating the utility of small molecule TLR inhibitors as pharmacological agents that might be administered in association with antibiotics to contain infection and suppress progression to preterm birth53. While clearly there are major challenges to consider in extrapolating this work to clinical application, we speculate that such TLR4 inhibitors may have particular value as prophylactic agents in threatened preterm labour where increased TLR4 expression disposes to elevated susceptibility, even in the absence of infection60,61, or when TLR4 SNPs associated with an increased risk of PTD and premature rupture of membranes are identified62,63. A likely advantage over current tocolytic agents is that TLR4 inhibitors act upstream of the pro-inflammatory cascade, overcoming the limitation of agents such as prostaglandin inhibitors which suppress uterine contractility, the final phase of labour, without impacting upstream pro-inflammatory activity45,64.

A key consideration is the impact on the neonate of in utero exposure to TLR4 inhibitors, and their effect on fetal capacity to withstand intrauterine inflammation, which is present to some extent in the majority of human preterm deliveries8. Sequalae of in utero inflammatory insult include fetal and newborn brain white matter disease, cerebral palsy, necrotizing enterocolitis, and chronic lung disease8, causing neurodevelopmental disability and a range of recurrent health problems in childhood5. Inflammation can provoke fetal brain injury even when inflammation is insufficient to activate parturition49, indicating the risk of sustained exposure to inflammatory mediators in utero. Clearly, clinical progression of this work requires extensive investigation of the benefits and risks of pharmacological delay of preterm birth for offspring, particularly effects on neurodevelopment, to ensure any treatment interventions adequately protect the fetus from inflammatory injury in utero.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57Bl/6 (B6) mice were obtained from Laboratory Animal Services, University of Adelaide and maintained in the specific pathogen-free University of Adelaide Medical School Animal House with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Animals were utilized in accordance with the NHMRC Australian Code of Practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes. All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Adelaide Animal Ethics Committee, using methods in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

One to three virgin female mice of 8–12 weeks of age were housed with a proven fertile B6 male and checked daily between 0800–1000 h for vaginal plugs, as evidence of mating. The morning of vaginal plug detection was designated gestational day (gd) 0.5. Females were removed from the male and housed individually.

Treatments and pregnancy outcomes, i.p. LPS model

Pregnant mice were administered lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 0.5 μg; S. typhimurium; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 200 μl PBS i.p., or PBS control, at 1100 h on gd 16.5; a protocol shown previously to induce PTD in ~50% of B6 mice40 41. Mice were immediately administered (+)-naloxone (60 mg/kg) in 100 μl PBS + 0.1% BSA i.p., or vehicle control, within 5 min of LPS injection on gd 16.5, plus a further 3 equivalent doses at 12 h intervals on gd 17.0, 17.5 and 18.0.

Mice were monitored for evidence of delivery at 12 h intervals after the gd 16.5 treatment until gd 18.5. Vaginal bleeding or the presence of intact or partial fetal tissue, viable or non-viable pups in the cage was noted. Delivery of live or dead pups before gd 18.0 was designated PTD. At gd 18.5 all mice were killed by cervical dislocation and the intact uterus was removed and analysed as described40. At autopsy, maternal outcomes were classified as pregnant with viable fetuses (at least one normal fetus of >800 mg); delivered early (>1 live pup born gd 18.0–18.5), delivered preterm with live pups (>1 live pup born gd 16.5–18.0), or delivered preterm with dead pups (gd 16.5–18.0, all pups dead). The % maternal outcome in each category for each treatment group was calculated as [number]/[total pregnant mice] × 100. Fetal outcomes were classified as viable in utero (normal fetus > 800 mg), non-viable in utero (fetus hemorrhagic, anemic, malformed, or severely growth retarded < 600 mg), delivered preterm, viable (fresh implantation scar, viable pup), delivered preterm, dead (fresh implantation scar, no viable pup) or resorbed (hemorrhagic mass < 5 mm in diameter). The % fetal outcome in each category for each treatment group was calculated as [number]/[total implantation site] × 100. When viable fetuses were present, each fetus was dissected from the amniotic sac and umbilical cord, fetuses and placentae were weighed, and the fetal:placental weight ratio calculated.

Treatment and pregnancy outcomes, in utero E. coli model

E. coli (serotype o55:K59(B5):H-) from American Type Culture Collection No. 12014 was grown overnight in 1000 ml Luria broth (LB) with shaking at 37 °C. Bacteria were washed by centrifugation in sterile PBS and killed at 100 °C for 20 min, verified by lack of growth overnight on LB agar plates. Prior to heat treatment, aliquots of live bacteria were plated on LB agar plates at 1 in 10 serial dilutions to quantify colony forming units (cfu). The heat-killed E. coli suspension was stored in aliquots of 1 × 1011 cfu/ml at −80 °C until use.

Pregnant mice were anesthetised with avertin at 1100 h on gd 16.5 and a 1.5 cm midline incision was made on the lower abdomen. Heat-killed E. coli (5 × 1010 cfu in 100 μl) or PBS was injected into the midsection of the left uterine horn at a site between two adjacent fetuses, in a treatment shown to elicit at least 50% PTD, as described28. The abdominal incision was closed in two layers, using sutures through the peritoneal wall and the skin. Mice were administered (+)-naloxone or vehicle as above immediately after wound closure, plus a further 3 doses at 12 h intervals as above, and allowed to recover. Females were monitored until birth for the time of parturition and the number of viable pups born, as above. Pups were weighed at 12–24 h post-delivery, at 8 days of age and at weaning.

Cytokine and uterine activation gene expression

A second cohort of pregnant females was administered E. coli or vehicle, as above. The site of injection was marked by a single interrupted suture through the uterus layer prior to injection. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation 4 h post-surgery and the intact uterus of each female was removed. The two implantation sites adjacent to the injection site were each dissected into uterine myometrium (between implantation sites), entire uterine decidua (at placental attachment site), placenta and fetal membranes, and snap-frozen in liquid N2, then stored at −80 °C.

Tissues were homogenised using ceramic beads (Mo Bio) in Trizol (Ambion RNA, Carlsbad CA) and RNA was precipitated using isopropanol and ethanol, then DNAse-treated using Ambion DNA-free™ Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity and concentration were determined by A260 and A280 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE) and RNA integrity was verified by denaturing agarose electrophoresis. First strand cDNA was reverse-transcribed from 2 μg extracted RNA with Superscript III (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with 200 ng random sequence oligohexamers (Geneworks, Adelaide, Australia) and 500 ng oligo dT18 (Proligo, Lismore, Australia) at 52 °C for 1 h. Each reaction contained 2 μL of cDNA (10 ng/μL) and 18 μL of master mix consisting of Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), 0.5–1 μM of 5′ and 3′ primers (listed in Supplementary Table S1) and RNase free water. PCR reactions were 10 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 sec and 60 °C for 45 sec, using a Rotorgene 6000 (Corbett Life Sciences, Sydney, Australia). PCR product integrity was confirmed by High Resolution Melt analysis. Data were normalized to β-actin mRNA expression and expressed as ΔΔCT using the formula mRNA level = Log2 - (CtBactin − Cttarget gene).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows, version 20.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Data were tested for normality using a Shapiro–Wilk test. ANOVA and post hoc T-tests were used when data were normally distributed. Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U-test were used when data were not normally distributed. Pregnancy outcome and fetal outcome data expressed as percentage were compared by χ2 analysis. Gestation length and viable litter size data expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) are analyzed by two-way ANOVA and post-hoc LSD test. Fetal weight, placental weight, fetal:placental weight ratio, growth trajectory and body composition data is expressed as estimated marginal means ± SEM and analysed by Mixed Model Linear Repeated Measures ANOVA and post-hoc LSD t-test, with mother as subject. Growth curve data was also analysed by Area Under the Curve (AUC) analysis in R studio. qPCR data are mean ± SEM analyzed by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Sidak t-test (to adjust for multiple comparisons). Differences between groups were considered significant when of p < 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chin, P. Y. et al. Novel Toll-like receptor-4 antagonist (+)-naloxone protects mice from inflammation-induced preterm birth. Sci. Rep. 6, 36112; doi: 10.1038/srep36112 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Goldenberg, R. L., Culhane, J. F., Iams, J. D. & Romero, R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 371, 75–84 (2008).

Mattison, D. R., Damus, K., Fiore, E., Petrini, J. & Alter, C. Preterm delivery: a public health perspective. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 15 Suppl 2, 7–16 (2001).

Blencowe, H. et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 379, 2162–2172 (2012).

Lawn, J. E., Cousens, S. & Zupan, J. & Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering, T. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet 365, 891–900 (2005).

Saigal, S. & Doyle, L. W. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 371, 261–269 (2008).

Doyle, L. W. & Anderson, P. J. Adult outcome of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics 126, 342–351 (2010).

Hui, L. L., Lam, H. S., Leung, G. M. & Schooling, C. M. Late prematurity and adiposity in adolescents: Evidence from “Children of 1997” birth cohort. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23, 2309–2314 (2015).

Romero, R., Dey, S. K. & Fisher, S. J. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science 345, 760–765 (2014).

Challis, J. R. et al. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci 16, 206–215 (2009).

Young, A. et al. Immunolocalization of proinflammatory cytokines in myometrium, cervix, and fetal membranes during human parturition at term. Biol Reprod 66, 445–449 (2002).

Osman, I. et al. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol Hum Reprod 9, 41–45 (2003).

Athayde, N. et al. A role for matrix metalloproteinase-9 in spontaneous rupture of the fetal membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179, 1248–1253 (1998).

Kelly, R. W. Inflammatory mediators and cervical ripening. J Reprod Immunol 57, 217–224 (2002).

Allport, V. C. et al. Human labour is associated with nuclear factor-kappaB activity which mediates cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression and is involved with the ‘functional progesterone withdrawal’. Mol Hum Reprod 7, 581–586 (2001).

Zaragoza, D. B., Wilson, R. R., Mitchell, B. F. & Olson, D. M. The interleukin 1beta-induced expression of human prostaglandin F2alpha receptor messenger RNA in human myometrial-derived ULTR cells requires the transcription factor, NFkappaB. Biol Reprod 75, 697–704 (2006).

Yoon, B. H. et al. Clinical implications of detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in the amniotic cavity with the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183, 1130–1137 (2000).

Harju, K. et al. Expression of toll-like receptor 4 and endotoxin responsiveness in mice during perinatal period. Pediatr Res 57, 644–648 (2005).

Moco, N. P. et al. Gene expression and protein localization of TLR-1, -2, -4 and -6 in amniochorion membranes of pregnancies complicated by histologic chorioamnionitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 171, 12–17 (2013).

Abrahams, V. M. et al. Divergent trophoblast responses to bacterial products mediated by TLRs. J Immunol 173, 4286–4296 (2004).

Gonzalez, J. M., Xu, H., Ofori, E. & Elovitz, M. A. Toll-like receptors in the uterus, cervix, and placenta: is pregnancy an immunosuppressed state? Am J Obstet Gynecol 197, 296 e291–e296 (2007).

Sheldon, I. M. & Roberts, M. H. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates the response of epithelial and stromal cells to lipopolysaccharide in the endometrium. PLoS One 5, e12906 (2010).

Wahid, H. H. et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is an essential upstream regulator of on-time parturition and perinatal viability in mice. Endocrinology, EN20151089 (2015).

Montalbano, A. P., Hawgood, S. & Mendelson, C. R. Mice deficient in surfactant protein A (SP-A) and SP-D or in TLR2 manifest delayed parturition and decreased expression of inflammatory and contractile genes. Endocrinology 154, 483–498 (2013).

Li, L., Kang, J. & Lei, W. Role of Toll-like receptor 4 in inflammation-induced preterm delivery. Mol Hum Reprod 16, 267–272 (2010).

Friebe, A. et al. Neutralization of LPS or blockage of TLR4 signaling prevents stress-triggered fetal loss in murine pregnancy. J Mol Med (2011).

Salminen, A. et al. Maternal endotoxin-induced preterm birth in mice: fetal responses in toll-like receptors, collectins, and cytokines. Pediatr Res 63, 280–286 (2008).

Wang, H. & Hirsch, E. Bacterially-induced preterm labor and regulation of prostaglandin-metabolizing enzyme expression in mice: the role of toll-like receptor 4. Biol Reprod 69, 1957–1963 (2003).

Filipovich, Y., Lu, S. J., Akira, S. & Hirsch, E. The adaptor protein MyD88 is essential for E coli-induced preterm delivery in mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200, 93 e91–e98 (2009).

Elovitz, M. A., Wang, Z., Chien, E. K., Rychlik, D. F. & Phillippe, M. A new model for inflammation-induced preterm birth: the role of platelet-activating factor and Toll-like receptor-4. Am J Pathol 163, 2103–2111 (2003).

Liu, H., Redline, R. W. & Han, Y. W. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces fetal death in mice via stimulation of TLR4-mediated placental inflammatory response. J Immunol 179, 2501–2508 (2007).

Hutchinson, M. R. et al. Non-stereoselective reversal of neuropathic pain by naloxone and naltrexone: involvement of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). Eur J Neurosci 28, 20–29 (2008).

Bradberry, J. C. & Raebel, M. A. Continuous infusion of naloxone in the treatment of narcotic overdose. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 15, 945–950 (1981).

Hutchinson, M. R. et al. Exploring the neuroimmunopharmacology of opioids: an integrative review of mechanisms of central immune signaling and their implications for opioid analgesia. Pharmacol Rev 63, 772–810 (2011).

Cheng, W. et al. HSP60 is involved in the neuroprotective effects of naloxone. Mol Med Rep 10, 2172–2176 (2014).

Jiang, X. et al. Inhibition of LPS-induced retinal microglia activation by naloxone does not prevent photoreceptor death. Inflammation 36, 42–52 (2013).

Wang, T. Y., Su, N. Y., Shih, P. C., Tsai, P. S. & Huang, C. J. Anti-inflammation effects of naloxone involve phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta and gamma. J Surg Res 192, 599–606 (2014).

Dailey, P. A. et al. The effects of naloxone associated with the intrathecal use of morphine in labor. Anesth Analg 64, 658–666 (1985).

Miller, R. R. et al. The effect of naloxone on the hemodynamics of the newborn piglet with septic shock. Pediatr Res 20, 707–710 (1986).

Law, W. R. & Ferguson, J. L. Naloxone alters organ perfusion during endotoxin shock in conscious rats. Am J Physiol 255, H1106–H1113 (1988).

Robertson, S. A., Skinner, R. J. & Care, A. S. Essential role for IL-10 in resistance to lipopolysaccharide-induced preterm labor in mice. J Immunol 177, 4888–4896 (2006).

Robertson, S. A. et al. Interleukin-6 is an essential determinant of on-time parturition in the mouse. Endocrinology 151, 3996–4006 (2010).

Dziarski, R., Wang, Q., Miyake, K., Kirschning, C. J. & Gupta, D. MD-2 enables Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)-mediated responses to lipopolysaccharide and enhances TLR2-mediated responses to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and their cell wall components. J Immunol 166, 1938–1944 (2001).

Elson, G., Dunn-Siegrist, I., Daubeuf, B. & Pugin, J. Contribution of Toll-like receptors to the innate immune response to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Blood 109, 1574–1583 (2007).

Hirsch, E., Filipovich, Y. & Mahendroo, M. Signaling via the type I IL-1 and TNF receptors is necessary for bacterially induced preterm labor in a murine model. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194, 1334–1340 (2006).

Challis, J. R. et al. Prostaglandins and mechanisms of preterm birth. Reproduction 124, 1–17 (2002).

Gao, L. et al. Steroid receptor coactivators 1 and 2 mediate fetal-to-maternal signaling that initiates parturition. J Clin Invest 125, 2808–2824 (2015).

Nadeau-Vallee, M. et al. Novel Noncompetitive IL-1 Receptor-Biased Ligand Prevents Infection- and Inflammation-Induced Preterm Birth. J Immunol 195, 3402–3415 (2015).

Rivera, D. L. et al. Interleukin-10 attenuates experimental fetal growth restriction and demise. FASEB J. 12, 189–197 (1998).

Elovitz, M. A. et al. Intrauterine inflammation, insufficient to induce parturition, still evokes fetal and neonatal brain injury. Int J Dev Neurosci 29, 663–671 (2011).

Kelly, A. J., Malik, S., Smith, L., Kavanagh, J. & Thomas, J. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD003101 (2009).

Cahill, R. J. et al. Universal DNA primers amplify bacterial DNA from human fetal membranes and link Fusobacterium nucleatum with prolonged preterm membrane rupture. Mol Hum Reprod 11, 761–766 (2005).

Fort, M. M. et al. A synthetic TLR4 antagonist has anti-inflammatory effects in two murine models of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol 174, 6416–6423 (2005).

Ng, P. Y., Ireland, D. J. & Keelan, J. A. Drugs to block cytokine signaling for the prevention and treatment of inflammation-induced preterm birth. Front Immunol 6, 166 (2015).

Robertson, S. A., Care, A. S. & Skinner, R. J. Interleukin 10 regulates inflammatory cytokine synthesis to protect against lipopolysaccharide-induced abortion and fetal growth restriction in mice. Biol Reprod 76, 738–748 (2007).

Sun, X. et al. Cnr2 deficiency confers resistance to inflammation-induced preterm birth in mice. Endocrinology 155, 4006–4014 (2014).

Timmons, B. C. et al. Prostaglandins are essential for cervical ripening in LPS-mediated preterm birth but not term or antiprogestin-driven preterm ripening. Endocrinology 155, 287–298 (2014).

Bo, Q. L. et al. Rosiglitazone pretreatment protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced fetal demise through inhibiting placental inflammation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 423, 51–59 (2016).

McGuire, W. & Fowlie, P. W. Naloxone for narcotic exposed newborn infants: systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 88, F308–F311 (2003).

Debelak, K., Morrone, W. R., O’Grady, K. E. & Jones, H. E. Buprenorphine + naloxone in the treatment of opioid dependence during pregnancy-initial patient care and outcome data. Am J Addict 22, 252–254 (2013).

Pawelczyk, E. et al. Spontaneous preterm labor is associated with an increase in the proinflammatory signal transducer TLR4 receptor on maternal blood monocytes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10, 66 (2010).

Kim, J. et al. Analysis of monocyte subsets and toll-like receptor 4 expression in peripheral blood monocytes of women in preterm labor. J Reprod Immunol 94, 190–195 (2012).

Lorenz, E., Hallman, M., Marttila, R., Haataja, R. & Schwartz, D. A. Association between the Asp299Gly polymorphisms in the Toll-like receptor 4 and premature births in the Finnish population. Pediatr Res 52, 373–376 (2002).

Rey, G. et al. Toll receptor 4 Asp299Gly polymorphism and its association with preterm birth and premature rupture of membranes in a South American population. Mol Hum Reprod 14, 555–559 (2008).

Iams, J. D. Prevention of preterm parturition. N Engl J Med 370, 1861 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by project and fellowship grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1026178 and APP465423), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (2011-09-15) and the Australian Research Council (DP110100297). A portion of this work was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Y.C. completed experiments, analysed data and prepared Figures, and assisted with drafting the manuscript; C.D. completed experiments and analysed data; M.R.H. contributed to experimental design, interpretation of data, and writing the manuscript. D.M.O. provided advice on interpretation of data, manuscript revisions, and contributed to securing funding. K.C.R. provided (+)-naloxone; L.M.M. contributed to analysing data and writing the manuscript; S.A.R. devised and oversaw the study, analysed and interpreted data, prepared the manuscript, and secured funding.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chin, P., Dorian, C., Hutchinson, M. et al. Novel Toll-like receptor-4 antagonist (+)-naloxone protects mice from inflammation-induced preterm birth. Sci Rep 6, 36112 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36112

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36112

This article is cited by

-

Interventions for Infection and Inflammation-Induced Preterm Birth: a Preclinical Systematic Review

Reproductive Sciences (2023)

-

Toll-like receptor-4 null mutation causes fetal loss and fetal growth restriction associated with impaired maternal immune tolerance in mice

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Pathogenesis of preterm birth: bidirectional inflammation in mother and fetus

Seminars in Immunopathology (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.