Abstract

Thorough mixing of the starting materials is the first step of a crystal growth procedure. This holds true for almost any standard technique, whereas the intentional separation of educts is considered to be restricted to a very limited number of cases. Here we show that single crystals of α-Li2IrO3 can be grown from separated educts in an open crucible in air. Elemental lithium and iridium are oxidized and transported over a distance of typically one centimeter. In contrast to classical vapor transport, the process is essentially isothermal and a temperature gradient of minor importance. Single crystals grow from an exposed condensation point placed in between the educts. The method has also been applied to the growth of Li2RuO3, Li2PtO3 and β-Li2IrO3. A successful use of this simple and low cost technique for various other materials is anticipated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The honeycomb iridates α-Li2IrO3 and Na2IrO3 attracted a lot of attention after Khaliullin and co-workers proposed that these systems offer a physical realization of the Kitaev interaction1 in a solid2,3. Motivated by their proposal, several experimental studies on single crystalline Na2IrO3 and polycrystalline α-Li2IrO3 have been performed4,5,6. Direct evidence for the entanglement between spatial and spin directions, which is a consequence of the Kitaev exchange coupling, was recently observed in Na2IrO3 by means of diffuse magnetic X-ray scattering7. These experiments were facilitated by the availability of sizable single crystals4, however, the microscopic details of the growth are not well understood.

For α-Li2IrO3 it has not been possible so far to obtain single crystalline material – not even on a length scale of 10 µm. Accordingly, there has been no direct access to the anisotropy of the physical properties, and the magnetic structure as well as the contribution of the Kitaev exchange has been still under debate.

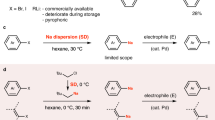

The growth procedure presented in this letter allows the growth of single crystals of α-Li2IrO3 of one millimeter along a side. A schematic sketch of the synthesis method and the phase formation as function of time and temperature are shown in Fig. 1. A remarkable feature is the isothermal nature of the process that was revealed by careful temperature measurements at different positions of the crucible (see Supplementary Figure 1): instead of a temperature gradient, here  , it is the formation of α-Li2IrO3 itself that drives the transport by maintaining a concentration gradient. The proposed, relevant transport equations are [ref. 8, p. 166, 217]:

, it is the formation of α-Li2IrO3 itself that drives the transport by maintaining a concentration gradient. The proposed, relevant transport equations are [ref. 8, p. 166, 217]:

Schematic description of the synthesis method (inset) and temperature profile.

Elemental Li and Ir are spatially separated in an open crucible. Upon heating in air Li initially forms solid LiOH that transforms to Li2O at T > 500 °C. Ir partially oxidizes to IrO2. The formation of α-Li2IrO3 takes place at T = 750–1050 °C. Single crystals grow from an exposed condensation point placed in between the educts.

Single crystalline α-Li2IrO3 forms from gaseous LiOH and IrO3. The X-ray diffraction pattern and the sharpness of the phase transition to the magnetically ordered state revealed a superior sample quality when compared to polycrystalline material (see below). Furthermore, the magnetic structure has been solved by recent single crystal magnetic resonant X-ray diffraction measurements performed on these samples (published separately9). The synthesis of α-Li2IrO3 was first reported by Kobayashi et al.10. Polycrystalline material was obtained by heating mixtures of Li2CO3 and IrO2 to temperatures between 650 °C–1050 °C. The presence of a low-spin Ir4+ state with an effective spin 1/2, as one of the essential ingredients of the Kitaev model, was reported soon after11. Despite the substantial interest in this material, the basic synthesis root has not changed since: to the best of our knowledge all attempts made are based on using Li2CO3 as starting material. Heating mixtures of Li2CO3 with Ir or IrO2 to sufficiently high temperatures leads to the formation of α-Li2IrO3 under release of CO2. This process, often referred to as ‘calcination’, has been applied to the growth of several other related materials, e.g.: Li2RuO312, Na2IrO313 or Na2PtO313. In this way comparatively large single crystals of Na2IrO3 were obtained4,7. The samples show a plate-like habit with typical lateral dimensions of a few square millimeter and a thickness of 100 μm. They grow out of a polycrystalline base (‘poly bed’) and form predominantly at the upper part of the product. For α-Li2IrO3, however, the similar approach leads to only a fine powder. Different flux methods, especially pre-sintered α-Li2IrO3 in LiCl flux, failed to increase the crystal size. Nevertheless, a better crystallinity was inferred from X-ray powder diffraction measurements14. In those attempts, the LiCl does not act as a ‘classical’ flux, it rather promotes a solid state reaction with enhanced diffusion.

At temperatures above 1000 °C the formation of α-Li2IrO3 competes with the high-temperature polytype β-Li2IrO315. After repetitive heating of α-Li2IrO3 at 1100 °C small single crystals up to several 10 μm of β-Li2IrO3 form16. Annealing β-Li2IrO3 at temperatures below 1000 °C did not lead to the formation of α-Li2IrO3, indicating that the transition is irreversible. Small single crystals of a third modification, the ‘harmonic’ honeycomb γ-Li2IrO3, were obtained by the calcination of Li2CO3 and IrO2 followed by annealing in molten LiOH at 700 °C to 800 °C17. An advantage of the calcination process is the ability to start from carbonates which are comparatively easy to handle and store. In contrast, elemental lithium is air sensitive and has been avoided as an educt in previous approaches. Furthermore, lithium reacts with many standard crucible materials and develops a moderately high vapor pressure (17 mbar at 900 °C18). On the other hand, elemental lithium has several advantages for the use as a flux. Its low melting point of 180 °C in comparison with a high boiling temperature of 1342 °C fulfill two key characteristics of a good flux19. Furthermore, lithium has a good solubility for iridium20. However, all our attempts to grow single crystals of α-Li2IrO3 from a lithium-rich flux and mixtures of lithium with LiCl, LiOH, LiBO2 and/or Li2CO3 failed. A comprehensive overview of those attempts is given in the Supplementary Table 1.

Comparatively large single crystals of several millimeter along a side, as observed for Na2IrO34,7 are not expected to grow in a solid state reaction due to the limited diffusion length. Given that the calcination process is completed at these temperatures (at 1050 °C) and the compound does not melt congruently indicates the relevance of a vapor transport process within the crucible. In order to investigate the possible formation and transport of Li-O, Ir-O, and/or Li-Ir-O gas specious during the syntheses of α-Li2IrO3, we started a growth attempt from elemental lithium and iridium in air. Lithium granules were placed on iridium powder in an Al2O3 crucible. The mixture was heated to 900 °C over 4 h, held for 72 h and quenched to room temperature. To our surprise, already the first attempt revealed α-Li2IrO3 single crystals of up to 50 μm along a side. The whole product appeared homogeneous and X-ray powder diffraction pattern showed only small amounts of IrO2 and Ir. This is even more surprising since only three small lithium granules (roughly 4 mm in length with a diameter of 1.5 mm) were used but α-Li2IrO3 formed over the whole bottom of the crucible (inner diameter of 16 mm). This observation strongly supports the idea of vapor transport playing a decisive role for the growth of this material. However, a classical vapor transport along a temperature gradient does not seem to take place: various growth attempts in a horizontal tube furnace indicated that once α-Li2IrO3 has formed it does not transport anymore. This observation is corroborated by an estimate of the free enthalpy of formation for α-Li2IrO3:  [M. Schmidt, MPI-CPfS, private communication]. It corresponds to a large, exothermic value of the free reaction enthalpy of

[M. Schmidt, MPI-CPfS, private communication]. It corresponds to a large, exothermic value of the free reaction enthalpy of  for the following equilibrium equation:

for the following equilibrium equation:

Therefore, we started to investigate the growth from spatially separated educts. For this purpose a specially designed setup has been constructed as depicted in Fig. 2a–c. It consists of a standard crucible, rings (washers), rings with spikes and a disc with a center hole (aperture). All parts are made from Al2O3. The rings act as spacers, hold the aperture in place and allow to vary the distance between starting materials and spikes.

Crystal growth equipment (crucible diameter 16 mm).

Arrangement of the materials before and after the growth process is depicted in (a,b), respectively. The rings with spikes are oriented like a spiral staircase in order to allow for nucleation at different positions with less intergrowth of the crystals. Formation of the largest α-Li2IrO3 single crystals is observed on spikes placed roughly 4 mm above the Ir starting material. (c) individual setup parts made from Al2O3 and (d) typical appearance of one of the lower spikes covered with α-Li2IrO3 crystals at the bottom side, scale bar 1 mm.

The spikes provide an exposed condensation point in between the educts. They are stacked as a ‘spiral staircase’ in order to identify the ideal position for the growth. The aperture is placed above the spikes and acts as a platform for one of the starting materials. The other educt is placed on the bottom of the crucible in the center of two spacers. This avoids a direct contact between the material and the spikes which sit on top of the spacers. For the growth of α-Li2IrO3, iridium metal powder and lithium granules are used as starting materials. Iridium is placed on the bottom of the crucible, lithium on top of the aperture. The distance between the elements is roughly 11 mm with five spikes placed in-between. The masses were chosen in their stoichiometric ratio. The whole setup is placed in a box furnace at 200 °C, heated to 1020 °C with a rate of 180 °C per hour, held for three days and finally quenched to room temperature. While heating, lithium transforms to a Li2O/LiOH mixture at moderate temperatures. At 900 °C all lithium is burned to Li2O. See a detailed analysis of this process in the Supplementary Figure 2. Only small amounts of Li2O are found on top of the aperture (where the lithium was placed) after the process. The iridium powder placed at the bottom is partially oxidized to IrO2. α-Li2IrO3 covers large parts of the spikes, with the largest crystals growing at the tip of the spikes, 3–4 mm above the iridium (Fig. 2d).

Single crystals of dimensions larger than 1 mm were obtained (Fig. 3a). A good sample quality is inferred from Laue-back-reflection (Fig. 3b): the diffraction pattern shows the (nearly) three-fold rotational symmetry of the honeycomb layers (along the c*-direction). The spot-size of the X-ray beam was similar to the sample dimensions. Figure 3c shows the temperature dependent specific heat measured on the same single crystal in comparison with polycrystalline material that was grown by calcination5. The improved sample quality of the single crystal is apparent from a sharper transition to the antiferromagnetically ordered state at TN = 15 K. Temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility for field applied parallel (χab) and perpendicular ( ) to the honeycomb layers is shown in Fig. 3d. An easy-plane behavior with a sharp decrease of χab at TN is observed, whereas

) to the honeycomb layers is shown in Fig. 3d. An easy-plane behavior with a sharp decrease of χab at TN is observed, whereas  decreases only slightly. A measurement performed on polycrystalline material5 is included for comparison and can be roughly described by

decreases only slightly. A measurement performed on polycrystalline material5 is included for comparison and can be roughly described by  for T > TN.

for T > TN.

Sample quality and magnetic anisotropy of α-Li2IrO3.

(a) comparatively large single crystal (1.2 mm × 0.4 mm × 0.5 mm and m = 1.7 mg) grown from separated educts (scale bar 0.3 mm). The corresponding Laue-back-reflection pattern, depicted in (b), shows the (nearly) three-fold rotation symmetry perpendicular to the honeycomb layers. (c) temperature dependent specific heat of the single crystal shown in (a) in comparison with a typical polycrystalline sample. (d) an easy-plane anisotropy is apparent from the temperature dependent magnetic susceptibility (μ0H = 1 T, χab : H⊥c*,  ).

).

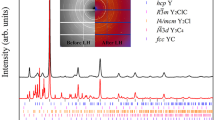

The structural order in the grown crystals was probed using X-ray diffraction and representative patterns are shown in Fig. 4a–d. The data are fully consistent with the expected monoclinic crystal structure21 of alternate stacking of honeycomb Li1/2IrO3 and hexagonal Li layers with space group C2/m (calculated patterns shown in Fig. 4e–f), and details of the full structural refinement are given in the Supplementary Note. Samples grown at 900 °C showed pronounced rods of diffuse scattering along the c* direction, normal to the layers, as evidenced in Fig. 4c. Rods of diffuse scattering with the same selection rule were also observed in the iso-structural materials Na2IrO3 and α-RuCl322 and attributed23 to occasional in-plane shifts of the stacked layers by ±b/3. Monitoring the structural order for different growth temperatures allowed us to optimize the synthesis parameters and obtain crystals with almost no detectable diffuse scattering (compare Fig. 4bc, and the intensity profile in Fig. 4g), showing that those crystals grown at 1020 °C are close to the limit of fully-coherent, three-dimensional structural ordering. Figure 4a,b show data from an un-twinned single crystal. Most as-grown crystals are twinned and a representative diffraction pattern shown in Fig. 4d can be understood by three additional twins: two twins rotated by ±120° around c*, and another twin with the a and c axes interchanged (for more details see Supplementary Note). We note that the susceptibility data in Fig. 3d was collected on a crystal that contained predominantly twins rotated by ±120° around c*, so under the assumption that the susceptibility tensor has only one unique axis c* (normal to the ab plane), all those twins had the same magnetic response in field applied along c* or perpendicular.

X-ray diffraction pattern from three different α-Li2IrO3 crystals:

one un-twinned and without stacking faults (sample 1, panels (a,b)), one predominantly a single grain, but with significant stacking faults manifested in extended diffuse scattering along l (sample 2, panel c), and one multi-twin crystal (sample 3, panel d). Color is intensity on a log scale. Vertical arrows near k = 2 in panels b,c show direction along which the intensity is plotted in panel g, note the strong contrast between sample 1 with sharp peaks at integer l and sample 2 where diffuse scattering dominates. Bottom graphs (e,f,h) show the calculated X-ray diffraction pattern in the same axes as the above panels a,b,d, for the nominal monoclinic crystal structure of α-Li2IrO321. Panel h includes contribution from C± twins (grains rotated by ±120° around c* leading to the peaks at fractional coordinates (0, k, n ± 1/3), with n integer and k = ±2, ±4) and an A-type twin responsible for the peaks at (0, k, ±1) with k odd (see Supplementary Note for details).

The method described is not restricted to the growth of α-Li2IrO3. Single crystals of β-Li2IrO3 and Li2RuO3 were also obtained (Fig. 5a,b, see Supplementary Figure 3 for X-ray diffraction pattern). Formation of the latter is expected from the similar transport behavior of Ir and Ru [ref. 8, p. 214 ff]. For Li2PtO3 we obtained polycrystalline material of good quality (Fig. 5c, see Supplementary Figure 3 for X-ray diffraction pattern). In conclusion, the technique should be applicable to various transport active elements in air in its simplest form. Application to a broader class of materials could be achieved by providing a controlled atmosphere (static or flowing) of, for example, oxygen, chlorine or iodine. The combination of an isothermal vapor transport in an open crucible with separated educts is unique and provides another approach for the crystal growth community.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Freund, F. et al. Single crystal growth from separated educts and its application to lithium transition-metal oxides. Sci. Rep. 6, 35362; doi: 10.1038/srep35362 (2016).

References

Kitaev, A. Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006).

Jackeli, G. & Khaliullin, G. Mott insulators in the strong spin-orbit coupling limit: from Heisenberg to a quantum compass and Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 017205 (2009).

Chaloupka, J., Jackeli, G. & Khaliullin, G. Kitaev-Heisenberg model on a honeycomb lattice: possible exotic phases in iridium oxides A2IrO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 027204 (2010).

Singh, Y. & Gegenwart, P. Antiferromagnetic Mott insulating state in single crystals of the honeycomb lattice material Na2IrO3 . Phys. Rev. B 82, 064412 (2010).

Singh, Y. et al. Relevance of the Heisenberg-Kitaev model for the honeycomb lattice iridates A2IrO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127203 (2012).

Ye, F. et al. Direct evidence of a zigzag spin-chain structure in the honeycomb lattice: a neutron and x-ray diffraction investigation of single-crystal Na2IrO3 . Phys. Rev. B 85, 180403 (2012).

Chun, S. H. et al. Direct evidence for dominant bond-directional interactions in a honeycomb lattice iridate Na2IrO3 . Nat. Phys. 11, 462–466 (2015).

Binnewies, M., Glaum, R., Schmidt, M. & Schmidt, P. Chemical Vapor Transport Reactions (de Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2012).

Williams, S. C. et al. Incommensurate counterrotating magnetic order stabilized by Kitaev interactions in the layered honeycomb α-Li2IrO3 . Phys. Rev. B 93, 195158 (2016).

Kobayashi, H. et al. Structure and charge/discharge characteristics of new layered oxides: Li1.8Ru0.6Fe0.6O3 and Li2IrO3 . J. Power Sources 68, 686–691 (1997).

Kobayashi, H., Tabuchi, M., Shikano, M., Kageyama, H. & Kanno, R. Structure, and magnetic and electrochemical properties of layered oxides, Li2IrO3 . J. Mater. Chem. 13, 957–962 (2003).

Dulac, J. F. Synthesis and crystallographic structure of a new ternary compound Li2RuO3 . C. R. l’Acad. Sci., Ser. B 270, 223–226 (1970).

McDaniel, C. L. Phase relations in the systems Na2O-IrO2 and Na2O-PtO2 in air. J. Solid State Chem. 9, 139–146 (1974).

Manni, S. Synthesis and investigation of frustrated Honeycomb lattice iridates and rhodates. Ph.D. thesis, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (2014).

Takayama, T. et al. Hyperhoneycomb iridate β-Li2IrO3 as a platform for Kitaev magnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 077202 (2015).

Biffin, A. et al. Unconventional magnetic order on the hyperhoneycomb Kitaev lattice in β-Li2IrO3: full solution via magnetic resonant x-ray diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 90, 205116 (2014).

Modic, K. A. et al. Realization of a three-dimensional spin–anisotropic harmonic honeycomb iridate. Nat. Commun. 5 (2014).

Honig, R. E. & Kramer, D. A. Vapor pressure data for solid and liquid elements. RCA Rev. 30, 285 (1969).

Jesche, A. & Canfield, P. C. Single crystal growth from light, volatile and reactive materials using lithium and calcium flux. Phil. Mag. 94, 2372–2402 (2014).

Massalski, T. B., Okamoto, H. & Subramanian, P. R. Binary Alloy Phase Diagrams, 2nd Edition (Volume 3) (A. S. M. International, Materials Park, OH, 1990).

O’Malley, M. J., Verweij, H. & Woodward, P. M. Structure and properties of ordered Li2IrO3 and Li2PtO3 . J. Solid State Chem. 181, 1803–1809 (2008).

Johnson, R. D. et al. Monoclinic crystal structure of α-RuCl3 and the zigzag antiferromagnetic ground state. Phys. Rev. B 92, 235119 (2015).

Choi, S. K. et al. Spin waves and revised crystal structure of honeycomb iridate Na2IrO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127204 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Schmidt, V. Tsurkan, A. Tsirlin, S. Manni, G. Hammerl, A. Erb, H. S. Jeevan, C. Krellner, S. Wurmehl, C. Geibel, T. Wolf, D. Schmitz and W. Scherer for fruitful discussions. For the technical support we like to thank A. Mohs, A. Herrnberger and K. Wiedenmann. This work has been supported by the German Science Foundation through projects TRR-80, SPP1666 and the Emmy Noether program − JE 748/1. Work in Oxford was partially supported by the EPSRC (UK) under Grants No. EP/H014934/1 and EP/M020517/1. R.D.J. acknowledges support from a Royal Society University Research Fellowship. In accordance with the EPSRC policy framework on research data, access to the data generated using EPSRC funds will be made available from X-ray data depository at http://dx.doi.org/10.5287/bodleian:O5YMYxv8R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.F. and A.J. developed the crystal growth technique. F.F. grew the single crystals and measured specific heat and magnetization. S.C.W., R.D.J. and R.C. performed and analyzed the X-ray diffraction experiments. F.F., S.C.W., P.G. and A.J. wrote the manuscript with the help of all authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Freund, F., Williams, S., Johnson, R. et al. Single crystal growth from separated educts and its application to lithium transition-metal oxides. Sci Rep 6, 35362 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35362

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35362

This article is cited by

-

Momentum-independent magnetic excitation continuum in the honeycomb iridate H3LiIr2O6

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Concept and realization of Kitaev quantum spin liquids

Nature Reviews Physics (2019)

-

Comparative study of monolithic platinum and iridium as oxygen-evolving anodes during the electrolytic reduction of uranium oxide in a molten LiCl–Li2O electrolyte

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2019)

-

Pressure-driven collapse of the relativistic electronic ground state in a honeycomb iridate

npj Quantum Materials (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.