Abstract

Catabolite control protein A (CcpA) is a highly conserved, master regulator of carbon source utilization in gram-positive bacteria, but the CcpA regulon remains ill-defined. In this study we aimed to clarify the CcpA regulon by determining the impact of CcpA-inactivation on the virulence and transcriptome of three distinct serotypes of the major human pathogen Group A Streptococcus (GAS). CcpA-inactivation significantly decreased GAS virulence in a broad array of animal challenge models consistent with the idea that CcpA is critical to gram-positive bacterial pathogenesis. Via comparative transcriptomics, we established that the GAS CcpA core regulon is enriched for highly conserved CcpA binding motifs (i.e. cre sites). Conversely, strain-specific differences in the CcpA transcriptome seems to consist primarily of affected secondary networks. Refinement of cre site composition via analysis of the core regulon facilitated development of a modified cre consensus that shows promise for improved prediction of CcpA targets in other medically relevant gram-positive pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is being increasingly appreciated that efficient acquisition and metabolism of nutrients are key aspects of bacterial pathogenesis1,2,3. Adaptation to various nutritional niches depends critically on the ability of bacteria to respond to diverse environmental stimuli4,5. Perception of these stimuli is relayed by regulatory proteins to effect changes at transcriptional and translational levels leading to adaptive changes at the cellular level6. Not surprisingly, therefore, regulatory proteins that affect basic bacterial physiology and metabolism have been found to be intimately linked to virulence in several infectious bacteria7,8,9. Carbon catabolite repression (CCR) is one of the most fundamental and highly conserved mechanisms which ensures optimal utilization of energy resources10. In many gram-positive bacteria, CCR is primarily mediated by the highly conserved catabolite control protein A (CcpA)11 which interacts with pseudo-palindromic cis-acting DNA motifs known as catabolite responsive elements (cre) to alter target gene expression12. In the presence of its phosphorylated co-effector histidine-containing protein HPr (HPr-Ser46-P), CcpA binds target DNA with increased affinity13. The production of HPr-Ser46-P by HPr kinase/phosphorylase (HPrK/P), in turn, is determined by the intra-cellular energy status and thus the CcpA-(HPr-Ser46-P) interaction links CcpA-mediated transcription to changing nutritional conditions14.

Several studies have demonstrated a connection between CcpA and the virulence of major gram-positive pathogens such as Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococccus aureus, Clostridium difficile, Bacillus anthracis and Enterococcus faecium15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. In light of the tremendous burden of gram-positive bacterial infections, CcpA is one of the most influential regulatory proteins modulating the virulence landscape of pathogenic bacteria26. Despite being extensively investigated for over 20 years, there remains numerous, critical knowledge gaps regarding CcpA function and its impact on bacterial pathogenesis. For example, although CcpA is known to affect expression of ~15% of the genomes of numerous bacterial species, the contribution of direct vs. indirect CcpA-mediated effects on transcription remains unclear15,27. Similarly, the role of CcpA in gram-positive bacterial virulence has primarily been studied in bacteremia models, which only represent a fraction of the types of infections that CcpA-containing bacteria cause28. Further information regarding the contribution of CcpA to gram-positive bacterial pathogenesis is needed given the potential role of the CcpA-(HPr-Ser46-P)-HPrK/P axis as a novel antimicrobial target29.

The majority of knowledge regarding CcpA-mediated effects on gene expression has occurred in the avirulent Bacillus subtilis which is distantly related to most organisms in which a role for CcpA in pathogenesis has been established16,21,30,31. In contrast, Group A Streptococcus (GAS) causes a wide range of infections in humans for which animal models are established32, is rendered less virulent by CcpA-inactivation and is closely related to other organisms whose infectivity is affected by CcpA-deletion such as S. pneumoniae and Streptococcus suis15,18. Thus, GAS can be used to assess the nature of the regulatory impact of CcpA on the infectivity of gram-positive pathogens. We previously established that CcpA-inactivation in a serotype M1 GAS strain affects the expression of ~15% of the genome and reduces lethality in a bacteremia infection model. There are >140 distinct M serotypes of GAS and inactivation of a regulatory protein can have dramatically different effects depending on the GAS serotype being studied33,34. Thus, we sought to study CcpA-inactivation in multiple GAS serotypes to test the hypotheses that the effect of CcpA-inactivation on GAS virulence is not serotype dependent and that comparative transcriptomics of GAS strains lacking CcpA would facilitate identification of the core GAS CcpA regulon.

Results and Discussion

CcpA deletion has serotype-specific effects

To improve understanding of the contribution of CcpA to the broad pathophysiology of GAS infections, we sought to analyze CcpA function in M serotype strains that are leading causes of GAS infections and are distantly related based on whole-genome phylogeny (Fig. 1a)35,36,37,38. We also used parental strains that are fully sequenced and known to lack mutations in the control of virulence (CovRS) two component system which affects the CcpA transcriptome because CovR and CcpA co-regulate numerous GAS genes39. Thus, we chose strains MGAS2221 (M1), MGAS10870 (M3) and MGAS6180 (M28) for our study36,37,38. The CcpA protein sequence in these three strains is identical (data not shown). Inactivation of CcpA in these three backgrounds resulted in a substantial growth defect in rich medium only for the serotype M3 strain MGAS10870 (Fig. 1b). Although why only the MGAS10870ΔccpA strain shows a growth defect is not known, importantly, this growth defect is recovered in the ccpA-complemented strain (Fig. 1b) attributing the absence of ccpA as the primary cause of the growth defect. Consistent with previous observations for serotype M1 strains, CcpA-inactivation reduced colony size in strain MGAS1087016,39. Conversely, MGAS6180 colonies were uniformly small and unaffected by the loss of ccpA (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Characterization of the GAS M serotype strains and their ccpA derivatives.

(a) Whole genome phylogeny of sequenced GAS strains. Complete GAS genomes of indicated M serotypes (blue) were obtained from NCBI. Relationships were inferred from 68,084 core single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci using SplitsTree. Location of parental strains used in this work are shown in red. (b) Growth curves for wild type, ccpA-inactivated and complemented strains in THY. Data points are mean and standard deviations from duplicate samples of each strain measured on two independent occasions.

CcpA affects GAS virulence in multiple infection models

The major disease manifestations of GAS in humans are bacteremia, necrotizing fasciitis, skin/soft tissue infection and pharyngitis, each of which have corresponding mouse models of infection40. Thus, we next assessed the contribution of CcpA to GAS virulence in each murine challenge model. Compared to their parental strains, all ccpA-inactivated strains caused significantly less mortality in the bacteremia model (Fig. 2a). We confirmed the lack of spurious mutations causing the observed differences by showing that complementation of the mutant strains with ccpA in trans restored virulence to wild-type levels (Fig. 2a). Similarly, in the myositis model, which mimics necrotizing fasciitis in humans, ccpA-inactivation significantly decreased mortality for all serotypes (Supplementary Fig. S2). Moreover, in the subcutaneous challenge model of skin/soft tissue infection, all three parental strains formed significantly larger ulcers than their ccpA-inactivated derivatives (Supplementary Fig. S2). Finally, following oropharyngeal challenge, a model for human pharyngitis, ccpA-inactivation caused a significant decrease in organism recovery for the M1 and M3 strains. However, we observed a significant increase in organism density over time for strain 6180ΔccpA compared to MGAS6180 (Fig. 2b). One possible explanation for these discordant results is the known inability of MGAS6180 to produce the broad-spectrum cysteine protease SpeB, which inactivates innate effector molecules present in human saliva41. Indeed, we found that CcpA-inactivation significantly decreased SpeB activity in MGAS2221 and MGAS10870, but did not affect the absence of SpeB production in MGAS6180 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Thus, in 11 of 12 animal challenge studies, CcpA-inactivation significantly decreased GAS virulence consistent with the idea that CcpA is critical to GAS pathogenesis across a diverse array of serotypes and infection models.

Effect of ccpA deletion on virulence of GAS serotype strains in mouse models of infection.

CD-1 swiss mice were inoculated with GAS strains by intraperitoneal (a) or intranasal (b) route. Mice were monitored to near-mortality for the bacteremia model (a) and survival was graphed. For the oropharyngeal model (b), throat swabs were obtained daily and the bacterial density was graphed. P values were derived from repeated measures analysis (see Methods).

Using a multi-serotype approach to define the core GAS CcpA regulon

Given that the CcpA regulon includes numerous transcription factors, the CcpA transcriptome consists of genes that are directly regulated by CcpA and those that are secondarily affected by CcpA-inactivation, but there is limited understanding of the relative contribution of direct vs. indirect CcpA-mediated regulation which in turn obscures precise characterization of CcpA-DNA interaction. We sought to better define genes that are directly regulated by CcpA by determining the CcpA transcriptome in multiple GAS serotypes with the idea that deletion of a highly conserved regulator should impact a core set of genes across multiple serotypes. Thus, we expect the “core” to consist mostly of conserved cre-bearing primary targets of CcpA and genes that are modulated by conserved CcpA-affected regulators. To this end, we performed RNAseq analyses in quadruplicate for the three serotype representatives and their ΔccpA mutants grown to mid-exponential phase in THY. RNAseq data has been deposited in GEO repository under the accession #GSE84641. Consistent with the reproducibility of the data, principal component analysis proved the transcriptomes of the wild-type and their ccpA-inactivated strains to be distinct in each serotype (Supplementary Fig. S4). We defined differentially expressed genes as those with a minimum mean transcript level difference of 2-fold and a corrected P value of ≤0.01. When analyzing genes that have homologs in all three serotypes, we observed significantly different transcript levels for 310, 386 and 307 genes in the ccpA mutants compared to their parental M1, M3 and M28 serotype strains respectively (Fig. 3a). This amounted to an average of 19% of ORFs in each serotype being differentially expressed, which is comparable to the observed CcpA regulon in Staphylococcus aureus (16%) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (14–19%)15,27. 173 genes were differentially expressed in all three serotypes thereby defining the core GAS CcpA regulon (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Table S1). Importantly, the core genes account for only 32% of the genes differentially expressed among the three serotypes indicating that our multi-serotype approach helped to remove serotype-specific genes that are unlikely to be directly regulated by CcpA. Supporting our hypothesis that the GAS CcpA core regulon was enriched for primary CcpA target genes, nearly 90% of the core genes were CcpA-repressed. This contrasted with an average of 63% repressed : 37% activated ratio when a particular serotype was studied (P < 0.001 by χ2 test; Supplementary Table S2). Of the 250 genes differentially regulated in only a single serotype, which accounted for 46% of all genes affected by CcpA-inactivation, only 35% were repressed by CcpA while 65% were activated. These findings suggest that much of CcpA-mediated activation, which has accounted for up to 40% of CcpA-influenced genes in previous investigations42, is unlikely to be a direct effect of CcpA, but rather to strain-specific regulatory circuits influenced by CcpA-inactivation. These data are in concert with those published in B. subtilis which identified only three operons as activated by CcpA43.

The effect of ccpA deletion on the GAS transcriptome.

(a) Linear representation of the genome of GAS serotype strains showing the effect of ccpA-inactivation on gene expression depicted as log fold change. (b) A weighted Venn diagram displaying the distribution and overlap of the CcpA-affected genes in all three serotypes was generated using the BioVenn application60. Arrows indicate the number of genes repressed (down) and activated (up) by CcpA in individual serotypes and in the core regulon. (c) Genes affected by CcpA in each serotype are shown by order of COG categories. Each colored circle denotes the enrichment of a specific COG in the serotype strain. [C] Energy production and conversion; [E] Amino acid transport and metabolism; [G] Carbohydrate transport and metabolism; [I] Lipid transport and metabolism; [J] Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis; [L] Replication, recombination and repair; [M] Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis; [N] Cell motility; [O] Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones; [R] General function prediction only; [S] Function unknown; [U] Intracellular trafficking, secretion and vesicular transport.

To better understand the functional impact of the CcpA regulon across serotypes, we assigned genes into cluster of orthologous groups (COGs). Five COGs were consistently enriched in all three serotypes of which carbohydrate transport and metabolism [G] comprised the largest number of genes (Fig. 3c). Two of these COGS, G and S, have also been reported to dominate the CcpA-influenced genes in other gram-positive pathogens20,27,31,42. However, several COGs, such as M (Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis), R (General function prediction only) and E (Amino acid transport and metabolism), that had previously been identified as part of the CcpA regulon in other species31,42 were only enriched in one or two of the GAS serotypes studied here suggesting that these particular COGs may be part of the strain-specific CcpA regulon rather than a core aspect of CcpA physiology.

Given the critical impact of CcpA on GAS pathogenesis, we determined how CcpA-inactivation affected known virulence gene transcript levels. Interestingly, only the nine gene operon encoding the cytolysin, streptolysin S (sagA-sagI)44, was influenced by CcpA in every serotype (Supplementary Fig. S5). CcpA-dependent serotype-specific variation was observed for the IL-8-degrading Streptococcus pyogenes cell envelope proteinase (SpyCEP) and the immunoglobulin cleaving endoglycosidaseS (EndoS) (Supplementary Fig. S5)45,46. The promoter regions of the spyCEP and endoS genes contained no clear distinctions to account for the serotype-specific differences. Taken together, we conclude that the multi-serotype transcriptomic approach allowed for clarification of the core CcpA regulon.

Functional cre sites are highly conserved across GAS serotypes

Although we postulate that serotype-specific CcpA-affected genes primarily represent indirect effects, it remains formally possible that the observed differences could be due to heterogeneity in cre site composition between homologs in the various serotypes (e.g. while the promoter of a gene specifically regulated in MGAS2221 contains a cre site, this site is absent in MGAS10870 and MGAS6180). We searched for cre sites within 150 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream of predicted translation start sites for all genes (only the first gene for operons) in MGAS2221, MGAS10870 and MGAS6180. We identified 72, 71 and 75 cre sites respectively, of which 68, 82 and 74% were differentially regulated by CcpA as demonstrated by RNA-seq (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Table S3). Of the 173 core genes, 103, 95 and 90 genes in serotypes M1, M3 and M28 respectively were present in operons with cre operators. In contrast, only 4, 10 and 11 of the 250 genes that displayed serotype-specific alteration in M1, M3 and M28 strains had cre sites (Fig. 4b). Consistent with our core transcriptome data indicating that CcpA mainly functions as a repressor, 92, 84 and 90% of the regulated cre-bearing genes were derepressed in the ccpA mutants of M1, M3 and M28 respectively (Fig. 4c). These data support the idea that serotype-specific variation as well as CcpA-mediated gene activation in GAS is primarily driven by indirect targets of CcpA.

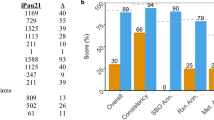

Distribution of cre and cre2 motifs.

(a) Percentage of cre and cre2-bearing operons that exhibit CcpA-dependent differential expression (DE) or do not (not), in the three GAS serotype strains. (b) Distribution of the core regulon genes based on the presence (cre) or absence (non-cre) of a cre site in the promoter. (c) Differentially regulated genes containing cre or cre2 operators displayed by relative percentages that are repressed (up) or activated (down) in ΔccpA. (d) Number of cre and cre2 sites in the GAS core CcpA regulon depicted as a Venn diagram.

Comparison of cre and cre2 sites in the GAS CcpA regulon

Although the vast majority of CcpA-DNA interaction has focused on cre sites12, a recent study assessing the targets of CcpA in S. suis reported a second CcpA-binding DNA motif, designated as cre2 42. Given that the CcpA protein in GAS and S. suis is highly conserved (79% identity), we next sought to determine the occurrence of cre2 sites in our representative GAS strains. A consensus motif developed from 45 cre2 sites reported in S. suis was used to search the regulatory region of the first genes of operons in MGAS2221, MGAS10870 and MGAS6180. Approximately 100 putative cre2 sites were identified in each serotype (Supplementary Table S4); nearly twice that reported in S. suis. The proportion of cre2-containing genes that had differential transcript levels were significantly lower compared to cre-bearing genes (P < 0.001, Fig. 4a). Moreover, genes with cre2 operators had a significantly lower frequency of CcpA-dependent repression than cre-containing genes (P < 0.001, Fig. 4c). The core GAS CcpA regulon has only 19 cre2-bearing operons compared to 35 cre-bearing operons, with 12 operons containing both (Fig. 4d). Thus, although cre2 sites might be involved in mediating CcpA-based regulation in a different growth phase or metabolic status of the cell, our data suggest that cre sites predominate in determining the CcpA regulon under the tested conditions.

Developing an improved cre motif

To this point, we had more clearly defined the core GAS CcpA regulon through our multi-serotype transcriptomic approach which facilitated removal of off-target effects that pervaded previous single strain studies. Thus, we next sought to use these data to optimize a cre consensus for GAS in particular and pathogenic gram-positive bacteria in general. Importantly, the cre site consensus derived from our GAS CcpA core regulon had several key differences from the B. subtilis motif (Fig. 5). A recent study reported a near absolute occurrence of Cytosine (C) and Guanine (G) at positions 8 and 9 in B. subtilis43. In GAS, the occurrence of C8 is also nearly absolute, but position 9 shows more flexibility, with almost 20% of the regulated genes coding for a nucleotide other than G at this position. The predominance of G at position 7 for B. subtilis is not observed for GAS, which showed greater variation (Fig. 5). There is also increased flexibility at position 3 in terms of its requirement of a G in GAS. In contrast, the requisite of a Thymine (T) at positions 11 and 12 is much more stringent in GAS compared to B. subtilis. The amino acid residues in the CcpA protein identified as interacting with these specific cre base pairs in a crystallographic analysis are highly conserved within the CcpA subfamily12 and show no differences between S. pyogenes and B. subtilis. However, there is increased amino acid variation between CcpA from GAS and B. subtilis in the C-terminal region, which has been shown to interact with the N-terminal DNA binding domain, that may account for the observed heterogeneity in cre site composition.

The improved GAS cre motif.

Weblogo representation of the GAS cre consensus motif. The frequency of occurrence of nucleotides for all core GAS cre sites is compared to that reported for B. subtilis43. Positions displaying notable differences between S. pyogenes and B. subtilis are marked with red boxes.

Next we sought to determine whether the GAS-optimized cre consensus (denoted as creGAS for the remainder of this manuscript) improves the ability to identify CcpA-regulated genes in major pathogenic gram-positive bacteria with published CcpA transcriptomes15,21. To this end, creGAS sites were predicted for S. aureus and S. pneumoniae and then compared to their published CcpA regulons to determine how many of our predicted creGAS sites have experimental evidence of CcpA-dependent gene expression changes. We then performed a similar comparison for the cre sites of S. aureus and S. pneumonia predicted by the RegPrecise47 database, which uses in sillico methods to curate regulons of various transcription factors. In S. pneumoniae, we predicted 60 sites in concert with RegPrecise, of which 39 (65%), have been confirmed to be regulated experimentally15 (Fig. 6a). We identified 68 sites not called by RegPrecise, of which 24 (35%) had reported CcpA-dependent regulation15. Among these were genes encoding an arginine deiminase and a neuraminate lyase, both of which contribute to S. pneumoniae virulence48,49. In contrast, of the 18 cre sites predicted by RegPrecise alone, only 3 (17%) were affected by CcpA-inactivation15. Similarly, in S. aureus we identified 17 creGAS sites that are present in CcpA-affected genes27 but were not predicted by RegPrecise whereas RegPrecise alone identified only 4 such sites (Fig. 6b). Hence, our creGAS consensus derived from our multi-strain approach proved to be a powerful tool to refine understanding of the CcpA regulons of pathogenic gram-positive organisms.

Prediction of cre operators in other gram-positive pathogens.

The suite of cre sites predicted for (a) S. pneumonia and (b) S. aureus using the creGAS and by RegPrecise (RP) are compared and displayed as Venn diagrams (calls). The RegPrecise database was accessed in November, 2015. Cre sites that have reported experimental evidence of CcpA-dependent expression are displayed in the lower panel (regulated genes).

Conclusions

Herein, we employed a multi-serotype approach to clarify the core GAS CcpA regulon, which we found to mainly consist of repressed genes that are likely to be directly affected by CcpA given the presence of cre elements. The power of this method is exemplified by the fact that only 173 of the 540 genes (32%) differentially regulated in the three serotypes were affected in all three strains. Thus, our data suggest that many of the previously published CcpA transcriptomes are likely to contain strain-specific, secondary effects of CcpA-inactivation. Our improved creGAS motif derived from the multi-strain transcriptome data should facilitate more accurate in sillico prediction of CcpA-regulated genes in a broad array of pathogens.

Interestingly, we observed that a significant proportion of the CcpA core regulon (55%) is non-cre-bearing. This observation could indicate an undiscovered, non-cre-based mode of CcpA regulation, such as the cre2 motif recently proposed in S. suis42. However, even incorporation of the cre2 motif accounted for only 15 additional genes in the core regulon. It remains possible that the core GAS CcpA regulon genes that lack cre or cre2 sites are part of the transcriptional regulatory network of a CcpA-affected regulator, given that the core CcpA regulon includes at least two TCSs, eight stand-alone regulators and two transcriptional antiterminator proteins (Supplementary Table S1).

The concept of metabolic regulators as virulence determinants is supported by the fact that the ability of a pathogen to thrive requires the capacity to exploit food sources in the host, which in turn relies on control of metabolic pathways. Thus, further understanding of CcpA function could assist in the development of novel preventive or therapeutic strategies applicable to numerous gram-positive pathogens.

Methods

Ethics Statement

Mouse experiments were conducted as per protocols approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol Number: 00000808). All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Bacterial Strains, media and growth

All strains used in this study are listed in Table S5. Group A Streptococcus (GAS) strains were routinely grown in Todd-Hewitt media supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Chloramphenicol (4 ug/ml) and spectinomycin (150 ug/ml) were used to select for the CcpA-complementing and CcpA-inactivating plasmids respectively. Non-polar insertional mutagenesis was employed to obtain isogenic ccpA mutants in each of the serotype strains as previously described for MGAS222139. The ccpA gene from each serotype strain was used to create their respective CcpA-complementing plasmid as described previously39 and introduced into these mutants for genetic complementation. Mutants and complemented strains were verified by Southern blots and qRT-PCR of ccpA and known CcpA-regulated genes (data not shown) as described previously50.

Animal Studies

Twenty five female outbred CD-1 Swiss mice (Harlan-Spraigue-Dawley) were used for each GAS strain for the bacteremia51 and the myositis52 models respectively. Mice were injected intraperitoneally (IP, bacteremia) and intramuscularly (IM, myositis) with 1 × 107 CFUs of MGAS2221 and MGAS10870 strains and their derivatives. In keeping with the less virulent nature of strain MGAS6180, we used 2 × 108 and 3.5 × 108 CFU for the IP and IM models respectively. Mice were observed until no deaths had occurred for 72 hrs in any group. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to compare the near-mortality rates and differences were considered statistically significant for a P < 0.05 after considering multiple comparisons. For the oropharyngeal model53, 35 mice were used for each of the GAS strains. We inoculated 1 × 107 CFUs of MGAS2221 and MGAS10870 and their derivative strains, whereas 2 × 108 CFUs were used for MGAS6180 and its derivative strains. The throats of all mice were swabbed before inoculation and daily after to determine GAS CFU density over time. For skin/soft tissue infections, immunocompetent hairless SKH1-hrbr female mice (Charles River BRF) were used, because the lack of hair facilitates lesion monitoring and excision. Twenty mice were used for each GAS strain tested and inoculated subcutaneously with 1 × 107 CFU of MGAS2221 and MGAS10870 and their derivative strains and 4 × 108 CFU MGAS6180 and its derivative strains. Development of ulcers were monitored and lesion sizes were measured daily until healing. Groups were compared using a Two Way ANOVA and considered significant for a P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. To ensure that observed phenotypic differences were not due to spurious mutations, we included the complemented strains in the bacteremia model. Given that complementation led to a restored phenotype in the bacteremia model, the complemented strains were not included in the remainder of the animal challenge studies in order to minimize animal numbers.

Statistics

For the bacteremia and the myositis models of infection, a total of 25 mice per strain was chosen because this number provides an 80% chance of detecting a 50% change in mortality rate using a log-rank test power calculation. The power calculation was based on previous studies done using strain MGAS2221 in this model. A total of 35 animals per strain was used for the pharyngeal challenge studies as this number provides an 80% chance of detecting a 35% reduction in pharyngeal colonization rates for the isogenic mutant strains compared to wild-type. The power calculation is based on pilot dose-challenge studies done with strain MGAS2221 and prior investigations with other GAS strains using this model. For skin/soft-tissue infection model, a total of 20 mice per strain was chosen because this number provides an 80% chance to detect a 30% decrease in median lesion size between the two strains. The power calculation was based on a pilot dose-escalation study using strain MGAS2221 and previous studies done using strain MGAS2221 in this model.

No inclusion/exclusion was applied to the animals and no randomization was used. All investigators were blinded for all the infection models using letter codes for each group. The code was broken only after completion of all analysis. Assumptions of normal distribution were tested in GraphPad Prism using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test when appropriate and variance was estimated using the F test.

Analysis of transcript levels

For RNA seq analysis, RNA was isolated from four replicate cultures from each strain grown to mid-exponential phase in THY (OD ~ 0.6) using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and processed as previously described50. Each Illumina FASTQ library was first processed by FASTX (version 0.0.6; http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/download.html) to remove low complexity and low quality reads. EDGE-pro v1.3 (Estimated Degree of Gene Expression in Prokaryotes) software54, was then used to align the reads using Bowtie2 v2.1.0 and estimate gene expression directly from the alignment output. For MGAS2221 and MGAS6180 strains, FASTA of the references genome sequences (.fna), protein translation table with coordinates of protein coding genes (.ptt) and a table containing coordinates of tRNA and rRNA genes for each strain was obtained from the NCBI database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria/Streptococcus_pyogenes_MGAS6180_uid58335/; ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria/Streptococcus_pyogenes_MGAS5005_uid58337/). As the MGAS2221 genome is not publicly available, we used the MGAS5005 genome, which is identical to MGAS222138 in gene content. For the MGAS10870 strain, the.ptt and.rnt files were generated from an in house genome assembly and were used as inputs into EDGE-pro. Gene names in MGAS10870 correspond to the previously defined open reading frames from the fully sequenced strains MGAS315. EDGE-pro was run with default parameters to generate a RPKM value table, except for defining the read length as 50 bp and using 64 threads (-t 32) on a Dell PowerEdge R910 (32-Core, 1Tb ram). RSeQC program was used for QC metrics and alignment statistics54. Samples were concatenated through edgeToDeseq.perl script provided by EDGE-pro. DESeq55 was used to identify the gene expression level (http://www.r-project.org). Differentially expressed genes between the wild-type and ΔccpA strains were considered significant based on a p-value ≤ 0.01. Over-represented COG group of differentially expressed genes were calculated by Fisher Exact test (p-values > 0.05) using in-house R script. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment was performed by Gorilla56.

For Taqman real-time qRT-PCR, strains were grown in duplicate on two separate occasions to mid-exponential phase in THY and processed as described previously50. The gene transcript levels between the wild-type and ccpA-inactivated derivative of each serotype strain was compared using an ordinary one way ANOVA. Primers and probes used are listed in Table S5.

In silico CcpA regulon identification

The CcpA regulon was predicted in silico using a classical probabilistic weight matrix strategy57. Briefly, we considered an operon as a cluster of genes encoding in the same direction with less than 50 base pairs between them58. We generated two independent CcpA binding site consensus weight matrices according to previously reported data42,43. Using the algorithm MAST59 each of the matrices was used to screen 150 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream of each operon contained in MGAS2221, MGAS6180 and MGAS 10870 strains of S. pyogenes genomes. Finally, we accepted only those CcpA binding site predictions which presented a similarity higher than 70% with the corresponding consensus matrix. Using the predicted CcpA binding site sequences conserved in the core regulon, we generated the new consensus matrix, creGAS and screened the complete genome of S. pneumoniae TIGR4 (NC_003028.3) and S. aureus Newman (NC_009641.1).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: DebRoy, S. et al. A Multi-Serotype Approach Clarifies the Catabolite Control Protein A Regulon in the Major Human Pathogen Group A Streptococcus. Sci. Rep. 6, 32442; doi: 10.1038/srep32442 (2016).

References

Pacheco, A. R. et al. Fucose sensing regulates bacterial intestinal colonization. Nature 492, 113–117 (2012).

Eisenreich, W., Dandekar, T., Heesemann, J. & Goebel, W. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacterial pathogens and possible links to virulence. Nat Rev Microbiol 8, 401–412 (2010).

Rohmer, L., Hocquet, D. & Miller, S. I. Are pathogenic bacteria just looking for food? Metabolism and microbial pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol 19, 341–348 (2011).

Santos-Beneit, F. The Pho regulon: a huge regulatory network in bacteria. Front Microbiol 6, 402 (2015).

Loughman, J. A. & Caparon, M. G. A novel adaptation of aldolase regulates virulence in Streptococcus pyogenes. Embo J 25, 5414–5422 (2006).

Stock, A. M., Robinson, V. L. & Goudreau, P. N. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 69, 183–215 (2000).

Munoz-Elias, E. J. & McKinney, J. D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence. Nat Med 11, 638–644 (2005).

Graham, M. R. et al. Analysis of the transcriptome of group A Streptococcus in mouse soft tissue infection. Am J Pathol 169, 927–942 (2006).

Jones, A. L., Knoll, K. M. & Rubens, C. E. Identification of Streptococcus agalactiae virulence genes in the neonatal rat sepsis model using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 37, 1444–1455 (2000).

Sonenshein, A. L. Control of key metabolic intersections in Bacillus subtilis. Nat Rev Microbiol 5, 917–927 (2007).

Warner, J. B. & Lolkema, J. S. CcpA-dependent carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67, 475–490 (2003).

Schumacher, M. A. et al. Structural basis for allosteric control of the transcription regulator CcpA by the phosphoprotein HPr-Ser46-P. Cell 118, 731–741 (2004).

Deutscher, J., Herro, R., Bourand, A., Mijakovic, I. & Poncet, S. P-Ser-HPr–a link between carbon metabolism and the virulence of some pathogenic bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1754, 118–125 (2005).

Deutscher, J., Francke, C. & Postma, P. W. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70, 939–1031 (2006).

Iyer, R., Baliga, N. S. & Camilli, A. Catabolite control protein A (CcpA) contributes to virulence and regulation of sugar metabolism in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 187, 8340–8349 (2005).

Shelburne, S. A. 3rd et al. A direct link between carbohydrate utilization and virulence in the major human pathogen group A Streptococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 1698–1703 (2008).

Kietzman, C. C. & Caparon, M. G. CcpA and LacD.1 affect temporal regulation of S. pyogenes virulence genes. Infect Immun (2009).

Willenborg, J. et al. Role of glucose and CcpA in capsule expression and virulence of Streptococcus suis. Microbiology 157, 1823–1833 (2011).

Somarajan, S. R., Roh, J. H., Singh, K. V., Weinstock, G. M. & Murray, B. E. CcpA is important for growth and virulence of Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun 82, 3580–3587 (2014).

Zeng, L. et al. Gene regulation by CcpA and catabolite repression explored by RNA-Seq in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 8, e60465 (2013).

Antunes, A. et al. Global transcriptional control by glucose and carbon regulator CcpA in Clostridium difficile. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 10701–10718 (2012).

Mertins, S. et al. Interference of components of the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system with the central virulence gene regulator PrfA of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 189, 473–490 (2007).

Chiang, C., Bongiorni, C. & Perego, M. Glucose-dependent activation of Bacillus anthracis toxin gene expression and virulence requires the carbon catabolite protein CcpA. J Bacteriol 193, 52–62 (2011).

Mendez, M. B., Goni, A., Ramirez, W. & Grau, R. R. Sugar inhibits the production of the toxins that trigger clostridial gas gangrene. Microb Pathog 52, 85–91 (2012).

Almengor, A. C., Kinkel, T. L., Day, S. J. & McIver, K. S. The catabolite control protein CcpA binds to Pmga and influences expression of the virulence regulator Mga in the group A Streptococcus. J Bacteriol 189, 8405–8416 (2007).

Holland, T., Fowler, V. G. Jr. & Shelburne, S. A. 3rd. Invasive gram-positive bacterial infection in cancer patients. Clin Infect Dis 59, Suppl 5, S331–S334 (2014).

Seidl, K. et al. Effect of a glucose impulse on the CcpA regulon in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol 9, 95 (2009).

Efstratiou, A. & Lamagni, T. Epidemiology of Streptococcus pyogenes. In Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations (eds. Ferretti, J. J., Stevens, D. L. & Fischetti, V. A. ) (Oklahoma City (OK), 2016).

Nessler, S. The bacterial HPr kinase/phosphorylase: a new type of Ser/Thr kinase as antimicrobial target. Biochim Biophys Acta 1754, 126–131 (2005).

Seidl, K. et al. Staphylococcus aureus CcpA affects virulence determinant production and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50, 1183–1194 (2006).

Carvalho, S. M., Kloosterman, T. G., Kuipers, O. P. & Neves, A. R. CcpA ensures optimal metabolic fitness of Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS One 6, e26707 (2011).

Tart, A. H., Walker, M. J. & Musser, J. M. New understanding of the group A Streptococcus pathogenesis cycle. Trends Microbiol 15, 318–325 (2007).

Ribardo, D. A. & McIver, K. S. Defining the Mga regulon: Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals both direct and indirect regulation by Mga in the group A Streptococcus. Mol Microbiol 62, 491–508 (2006).

Dmitriev, A. V., McDowell, E. J. & Chaussee, M. S. Inter- and intraserotypic variation in the Streptococcus pyogenes Rgg regulon. FEMS Microbiol Lett 284, 43–51 (2008).

Steer, A. C., Law, I., Matatolu, L., Beall, B. W. & Carapetis, J. R. Global emm type distribution of group A streptococci: systematic review and implications for vaccine development. Lancet Infect Dis 9, 611–616 (2009).

Beres, S. B. et al. Molecular complexity of successive bacterial epidemics deconvoluted by comparative pathogenomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 4371–4376 (2010).

Green, N. M. et al. Genome sequence of a serotype M28 strain of group A Streptococcus: potential new insights into puerperal sepsis and bacterial disease specificity. J Infect Dis 192, 760–770 (2005).

Sumby, P. et al. Evolutionary origin and emergence of a highly successful clone of serotype M1 group A Streptococcus involved multiple horizontal gene transfer events. J Infect Dis 192, 771–782 (2005).

Shelburne, S. A. et al. A combination of independent transcriptional regulators shapes bacterial virulence gene expression during infection. PLoS Pathog 6, e1000817 (2010).

Carapetis, J. R., Steer, A. C., Mulholland, E. K. & Weber, M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 5, 685–694 (2005).

Stetzner, Z. W. et al. Serotype M3 and M28 Group A Streptococci Have Distinct Capacities to Evade Neutrophil and TNF-alpha Responses and to Invade Soft Tissues. PLoS One 10, e0129417 (2015).

Willenborg, J., de Greeff, A., Jarek, M., Valentin-Weigand, P. & Goethe, R. The CcpA regulon of Streptococcus suis reveals novel insights into the regulation of the streptococcal central carbon metabolism by binding of CcpA to two distinct binding motifs. Mol Microbiol 92, 61–83 (2014).

Marciniak, B. C. et al. High- and low-affinity cre boxes for CcpA binding in Bacillus subtilis revealed by genome-wide analysis. BMC Genomics 13, 401 (2012).

Molloy, E. M., Cotter, P. D., Hill, C., Mitchell, D. A. & Ross, R. P. Streptolysin S-like virulence factors: the continuing sagA. Nat Rev Microbiol 9, 670–681 (2011).

Turner, C. E., Kurupati, P., Jones, M. D., Edwards, R. J. & Sriskandan, S. Emerging role of the interleukin-8 cleaving enzyme SpyCEP in clinical Streptococcus pyogenes infection. J Infect Dis 200, 555–563 (2009).

Collin, M. & Olsen, A. EndoS, a novel secreted protein from Streptococcus pyogenes with endoglycosidase activity on human IgG. EMBO J 20, 3046–3055 (2001).

Novichkov, P. S. et al. RegPrecise 3.0–a resource for genome-scale exploration of transcriptional regulation in bacteria. BMC Genomics 14, 745 (2013).

Gupta, R. et al. Deletion of arcD in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39 impairs its capsule and attenuates the virulence. Infect Immun (2013).

Brittan, J. L., Buckeridge, T. J., Finn, A., Kadioglu, A. & Jenkinson, H. F. Pneumococcal neuraminidase A: an essential upper airway colonization factor for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Oral Microbiol 27, 270–283 (2012).

Horstmann, N. et al. Dual-site phosphorylation of the control of virulence regulator impacts group a streptococcal global gene expression and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 10, e1004088 (2014).

Sumby, P., Whitney, A. R., Graviss, E. A., DeLeo, F. R. & Musser, J. M. Genome-wide analysis of group A streptococci reveals a mutation that modulates global phenotype and disease specificity. PLoS Pathog 2, e5 (2006).

Turner, C. E., Kurupati, P., Wiles, S., Edwards, R. J. & Sriskandan, S. Impact of immunization against SpyCEP during invasive disease with two streptococcal species: Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus equi. Vaccine 27, 4923–4929 (2009).

Shelburne, S. A. 3rd et al. Maltodextrin utilization plays a key role in the ability of group A Streptococcus to colonize the oropharynx. Infect Immun 74, 4605–4614 (2006).

Magoc, T., Wood, D. & Salzberg, S. L. EDGE-pro: Estimated Degree of Gene Expression in Prokaryotic Genomes. Evol Bioinform Online 9, 127–136 (2013).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11, R106 (2010).

Eden, E., Navon, R., Steinfeld, I., Lipson, D. & Yakhini, Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 48 (2009).

Travisany, D. et al. A new genome of Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans provides insights into adaptation to a bioleaching environment. Res Microbiol 165, 743–752 (2014).

McGuire, A. M., Hughes, J. D. & Church, G. M. Conservation of DNA regulatory motifs and discovery of new motifs in microbial genomes. Genome Res 10, 744–757 (2000).

Bailey, T. L., Williams, N., Misleh, C. & Li, W. W. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 34, W369–W373 (2006).

Hulsen, T., de Vlieg, J. & Alkema, W. BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics 9, 488 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by RO1 AI089891 (S.A.S), FONDECYT N°11150679, Center for Genome Regulation FONDAP 15090007 and Basal grant of the Center for Mathematical Modeling UMI2807 UCHILE-CNRS N° PFB03 project (D.T., M.G., A.Ma. and M.L.). We acknowledge the CCSG P30 CA016672 funds for the Bioinformatics Shared Resource, the Research Animal Support Facility and the Sequencing and Microarray facility at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D., S.A.S., J.G.P. and N.H. designed the research, S.D., M.S., A.M., J.G.P., N.H. and S.A.S. did the experiments, S.D., H.Y., D.T., M.G., A.Ma. and M.L. performed data analysis and S.D., S.A.S. and M.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

DebRoy, S., Saldaña, M., Travisany, D. et al. A Multi-Serotype Approach Clarifies the Catabolite Control Protein A Regulon in the Major Human Pathogen Group A Streptococcus. Sci Rep 6, 32442 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32442

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32442

This article is cited by

-

Functional analysis of the role of CcpA in Lactobacillus plantarum grown on fructooligosaccharides or glucose: a transcriptomic perspective

Microbial Cell Factories (2018)

-

Glucose Levels Alter the Mga Virulence Regulon in the Group A Streptococcus

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.