Abstract

Electrical stimulation is a common adjunct used to promote bone healing; its efficacy, however, remains uncertain. We conducted a meta-analysis of randomized sham-controlled trials to establish the efficacy of electrical stimulation for bone healing. We identified all trials randomizing patients to electrical or sham stimulation for bone healing. Outcomes were pain relief, functional improvement, and radiographic nonunion. Two reviewers assessed eligibility and risk of bias, performed data extraction, and rated the quality of the evidence. Fifteen trials met our inclusion criteria. Moderate quality evidence from 4 trials found that stimulation produced a significant improvement in pain (mean difference (MD) on 100-millimeter visual analogue scale = −7.7 mm; 95% CI −13.92 to −1.43; p = 0.02). Two trials found no difference in functional outcome (MD = −0.88; 95% CI −6.63 to 4.87; p = 0.76). Moderate quality evidence from 15 trials found that stimulation reduced radiographic nonunion rates by 35% (95% CI 19% to 47%; number needed to treat = 7; p < 0.01). Patients treated with electrical stimulation as an adjunct for bone healing have less pain and are at reduced risk for radiographic nonunion; functional outcome data are limited and requires increased focus in future trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone healing is a complex physiological process and is the end goal in the treatment of patients with fractures, surgical osteotomies and spinal fusion procedures. Failure or delays in bone healing often require further intervention and may result in serious morbidity such as increased pain and functional limitations1. Secondary procedures to promote bone healing may be invasive, expensive, and result in significant patient morbidity. The socioeconomic burden associated with bone healing complications such as delayed union or nonunion is substantial and includes direct treatment costs as well as personal and societal costs, such as lost wages, decreased productivity and delays returning to work2,3,4.

Electrical stimulation is a popular adjunctive therapy used to promote bone healing across a range of indications5,6. Basic science research suggests that electrical stimulation enhances the process of bone healing by stimulating the calcium-calmodulin pathway secondary to the upregulation of bone morphogenetic proteins, transforming growth factor-β and other cytokines3,7,8,9,10,11. Clinical evidence to support the use of electrical stimulators for bone healing has been inconclusive. Prior systematic reviews of electrical stimulation have been limited by narrow scope, poor methodologic quality, and a focus on radiographic healing over patient-important outcomes12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. We performed a meta-analysis of randomized sham-controlled trials to determine the effect of electrical stimulation on bone healing, focusing on patient-important outcomes.

Methods

We report this study according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement20 and the protocol for reviews outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions21.

Identification of Studies

We systematically searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library from inception of the database to March 6, 2016. We used MeSH and EMTREE headings in various combinations and supplemented with free text to increase sensitivity (Appendix 1). Manual searches of the reference lists of included trials were conducted to identify any additional articles. We hand-searched major orthopaedic conference proceedings from March 2013 to March 2016 to identify unpublished studies that were potentially eligible.

Assessment of eligibility

Two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts and applied eligibility criteria to the methods section of potentially eligible trials using an electronic screening form. All discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

We included all studies fulfilling the following criteria:

1) Adult patients >16 years of any sex undergoing operative or nonoperative treatment for a fresh fracture, nonunion, delayed union, osteotomy, or symptomatic spinal instability requiring fusion.

2) Trials comparing direct current (DC), capacitive coupling (CC), or pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMF).

3) Randomized sham-controlled trials (RCT) only22.

No restrictions were made for publication date, language, presence or absence of co-interventions, or length of follow-up. Studies using multiple bones in the same patients as the unit of randomization, rather than patients were excluded due to lack of independence23.

Assessment of risk of bias

Two reviewers independently performed outcome-specific assessment of risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for risk-of-bias assessment21. Attempts were made to contact study authors to resolve any uncertainties when required. When the issues bearing on the risk of bias were identical across outcomes within a study, a single risk of bias assessment was reported24.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data using a piloted electronic data extraction form. Extracted data included author names, journal names and publication year, funding source, sample size, mean ages and proportion of each sex in treatment and control groups, descriptions of the interventions in each group, all reported outcomes and follow-up times, and loss to follow-up. We attempted to contact study authors for clarification if important data were unclear or not reported.

Radiographic healing was determined according to the methods implemented in each trial. When multiple criteria for union were described, we recorded the most conservative estimate of union. For each trial we determined whether radiographic assessment was blinded or independently assessed and judged by consensus whether the determination of union was reasonable or not reasonable. We converted radiographic union rates to the number of nonunions by subtracting from the total number of patients in each group. For patients already presenting with a nonunion or delayed union, we recorded the number of patients with persistent or on-going nonunions. In trials that reported union based on CT-scan and plain radiographs, we recorded plain film radiographic healing for consistency.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated agreement for reviewers’ assessments of study eligibility with the Cohen’s kappa coefficient and agreement for assessments of risk of bias using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Kappa values ≥0.65 were considered adequate25.

Among eligible trials we found substantial diversity in the types of bone lesions targeted for treatment. Although baseline bone healing time differs by size of bone and the site of lesion, the biologic process of healing is consistent across all bone lesions26,27,28,29 and the effect of electrical stimulation compared with control on the time to bone healing is therefore likely to be similar. We reasoned that pooling trials exploring the effect of electrical stimulation for different bone lesions would increase the generalizability of our results30. We explored the validity of this assumption. We further anticipated that different forms of electrical stimulation may produce different effects, and explored this issue.

We utilized the conservative random-effects model of DerSimonian and Laird to pool effect estimates21,31. Our primary meta-analysis was an intention-to-treat analysis in which all patients were analysed in the groups to which they were originally randomized. We reported pooled estimates as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) was used to calculate the Number Needed to Treat (NNT) when applicable to aid interpretability32,33. Continuous outcome instruments measuring the same constructs were summarized using mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs21. If standard deviations were not available, they were estimated from trials with similar outcomes21,34. We transformed pain scores expressed in different units to the 0 to 100 mm visual analogue scale to facilitate pooling as a weighted mean difference. When there were at least 10 studies in a particular meta-analysis, we examined publication bias by using funnel plots comparing sample size versus treatment effect across the included trials21. All tests of significance were two-tailed and p-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Evaluation of heterogeneity

We quantified heterogeneity using the Χ2test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic21. I2 values were interpreted according to the Cochrane Handbook21 as: 0–30% might not be important, 30–60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50–90% substantial heterogeneity and 75–100% considerable heterogeneity. We prespecified the following two subgroup hypotheses to explain potential heterogeneity35.

-

1

Clinical indication: fresh fractures, delayed union or nonunion, spinal fusion, or surgical osteotomy.

-

2

Type of stimulation: direct current (DC), capacitive coupling (CC), or pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF).

For each subgroup, we performed tests for interaction using a chi-square significance test36.

Sensitivity Analyses

Our main reported analysis is a complete case analysis in which participants with missing data were excluded from both the numerator and denominator. To explore the effects of missing outcome data, we performed sensitivity analyses. For the control group, we assumed the event rate to be the same for patients with missing data and those successfully followed; for the treatment group we assumed plausible ratios of event rates in patients with missing data compared with those who were successfully followed at ratios of: 1.5:1, 2:1, and 2.5:137. As such, we tested the robustness of the results of the primary meta-analysis under relatively extreme assumptions with variable degrees of plausibility37,38. When only total losses to follow-up were reported and not specific numbers of losses in each arm, we assumed that losses in each arm were equal.

Given potential variability in the methods used to evaluate radiographic union39,40,41 we performed three further sensitivity analyses: (1) including only trials in which an independent assessor was used to determine radiographic union; (2) including only trials in which consensus judgment was reasonable with regards to overall determination of union; (3) including only trials that defined union as >70% of bony continuity, or three of four cortices, as the most conservative estimate of bony union.

GRADE quality assessment and summary of findings

We utilized the GRADE approach to summarize the quality of the evidence for or against the use of electrical stimulation by each outcome. Data from randomized controlled trials were considered high-quality evidence, but could have been rated down according to risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, or publication bias42.

Results

Eligible and Included Studies

Of 2025 potentially eligible articles, 1664 titles and abstracts were screened and 17 were eligible for our review. However, the authors of one trial43 clarified that the same patients were included in a more recent manuscript44 and Anderson et al. reported different outcomes of the same patient population in two separate publications45,46. Thus 15 trials that were reported in 16 manuscripts44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 with a total of 1247 patients were included (Fig. 1). No additional trials from conference proceedings were identified. Agreement between the reviewers for eligibility based on title and abstract screening was very high (kappa = 0.85, 95% CI 0.78–0.93).

Study characteristics

Mean age of study participants was 45 years in the experimental and control arm. The proportion of male patients in the experimental and control arm was 58.3% and 56.3%, respectively. Mean follow-up was 8.2 (SD 3.4) months for radiographic outcomes and 8.6 (SD 3.7) months for pain and function (Appendix 2).

Four trials included patients undergoing a spinal fusion45,46,49,52,55, five trials evaluated fresh fracture treatment44,47,50,51,54,60, five trials examined treatment of delayed or nonunions48,56,57,58,59 and one study included patients undergoing surgical osteotomy53. Trials of the appendicular skeleton assessed patients with tibial or femoral fractures47,48,53,54,57,59, femoral neck44, scaphoid fractures50,51, and other long-bone fractures56,58.

Twelve trials reported use of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy, one trial reported direct current (DC) stimulation and two trials reported continuous current (CC) stimulation. Details with regards to specific stimulator type, frequency and treatment duration for each study are reported in Appendix 3.

Radiographic union was described in all 15 of the included trials (Appendix 4). Consensus judgment with regards to the overall determination of union was deemed to be reasonable in all but four studies48,54,56,59. Sharrard57 reported results of radiographic union read by both orthopaedic surgeons and radiologists separately.

Pain was reported in four trials using either the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)44, Dallas Pain Questionnaire (DPQ)46 or a categorical pain scale48,57. The lower and upper limits of the categorical pain scale reported in one study57 (with demised single author) was assumed to be 0 to 5 based on the reported mean and standard deviations and a statistical simulation. Functional outcome was reported using components of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey in two trials46,47.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias assessments are presented in Fig. 2. The funnel plot for radiographic nonunion at last follow-up was symmetric and did not suggest publication bias (Fig. 3)21.

Pain and function

Pain was reported across four trials44,46,48,57 including a total of 195 patients. The pooled estimate of effect between electrical stimulation and sham control showed a statistically significant difference in pain (MD on the 100 mm visual analogue scale = −7.67 mm, 95% CI −13.92 to −1.43; p = 0.02; I2 = 0%; Fig. 4). In the GRADE quality assessment (Table 1) pain was rated as moderate quality due for imprecision given that the 95% CI includes values below and above the minimal important difference (MID) of 10 mm61. We found no evidence to support a difference in treatment effect due to treatment indication (interaction p = 0.41) or stimulator type (interaction p = 0.19).

Functional outcomes were compared in two trials that reported SF-36 scores (n = 316 patients). The pooled estimate of effect between electrical stimulation and control was not statistically significant (MD −0.88, 95% CI −6.63 to 4.87, p = 0.76) (Fig. 5). In the GRADE quality assessment, functional outcome was rated as low quality evidence due to risk of bias (high losses to follow-up in both studies46,47) and inconsistency due to unexplained heterogeneity (I2 = 57%)62.

Radiographic nonunion

Radiographic nonunion was compared across 15 trials with 1247 patients. The pooled estimate of effect between electrical stimulation and sham controls at last reported follow-up up to 12 months found that electrical stimulation reduced the relative risk for nonunion or persistent nonunion by 35% (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.81, p < 0.01, moderate certainty) and the absolute risk by 15%. Overall between-study heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 46%; p = 0.02) (Fig. 6). Interpreted another way, for every 7 patients treated with electrical stimulation, 1 nonunion or persistent nonunion could be averted (NNT = 7). In the GRADE quality assessment radiographic nonunion was rated as moderate quality evidence due to indirectness (Table 1). We found no evidence to support a difference in treatment effect due to treatment indication (interaction p = 0.75) or stimulator type (interaction p = 0.05) (Appendices 5 and 6). An analysis conducted with the spine studies removed still showed a significant pooled treatment effect in favor of electrical stimulation for acute fracture, nonunion or delayed union, and osteotomy (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.91, p = 0.01).

Sensitivity Analyses

Our complete case analysis showed a significant difference (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.80) that remained robust when assumed nonunion rates in patients with missing data were 1.5:1 and 2:1. When the assumed nonunion rates in patients with missing data went up to 2.5:1 the pooled estimate of effect was no longer significant (Appendix 7).

In only trials in which an independent assessor was used to determine union, a significant difference in favor of electrical stimulation was found (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.87, p < 0.01). Trials in which consensus judgment deemed the definition and assessment as reasonable showed a significant difference in favor of electrical stimulation (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.85, p < 0.01). Finally, the most conservative estimate in only those trials44,47,50,51,52,53,57,58 explicitly defining union as >75% of bony continuity also favored electrical stimulation (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.91, p < 0.01).

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis of eligible randomized controlled trials found moderate quality evidence for electrical stimulation in reducing patient-reported pain and radiographic nonunion or persistent nonunion. Low-quality functional outcome data showed no difference with electrical stimulation compared to sham treatment.

Our findings are strengthened by our comprehensive search and broad clinical eligibility criteria, and by including only randomized sham-controlled trials. We hypothesized the effect of electrical stimulation on bone healing would be similar across different types of stimulation and different clinical lesions, and our subgroup analyses support this assumption. We found no evidence to support a difference in treatment effect due to treatment indication (interaction p = 0.75). In keeping with other orthopaedic trials of bone healing, most trials reported only surrogate end points. Limited reporting of patient-important outcomes is highlighted in this review and has been identified as a significant problem in the surgical literature63,64. The calculation of Minimally Important Differences (MIDs) can further aid the interpretation of treatment effects, but they are often context- or instrument- specific and may have limited generalizability across clinical indications or varying pain measures65,66. Although we found the mean difference in pain statistically significant, it is possible that this may not represent a difference important to patients67.

A Cochrane review published in 2011 reported non-significant differences for electrical stimulation in improving union rates in four trials involving 125 patients15. Two reviews done in 2014 also showed an inconclusive benefit of electrical stimulation. Hannemann et al.51,60 performed a systematic review evaluating the effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) and electrical stimulation specifically in acute fractures; results for LIPUS and electrical stimulation, however, were pooled together and not reported separately. In 2013, Tian et al. conducted a meta-analysis looking at the efficacy of various types of electrical stimulation on spinal fusion18. Randomized trials and observational trials were, however, combined to provide a pooled estimate and no assessment of methodological quality or risk of bias was performed.

A previous review performed by our group in 200816 specifically assessed long-bone fracture healing and failed to show a significant impact of electrical stimulation on radiographic healing, and inconsistent results for pain relief. In 201414, we performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis to indirectly comparing low-intensity pulsed ultrasonography (LIPUS) and electrical stimulation. Results were pooled separately by 3, 6 and 12-month time points and a borderline significant effect in improving union rates in nonunions or delayed unions at 3 months with electrical stimulation but not at 6 or 12 months was seen. Two trials included in that review, however, were found to have used the same patient groups on contact with the authors43,44. The present review’s results differ given that our interpretation of the evidence is based upon the addition of 6 recent trials (424 patients) relating to fresh fractures, nonunions/delayed unions and osteotomies44,47,50,51,54,58 (Table 2). Moreover, we restricted eligible trials to only sham-controlled randomized trials and assessed both patient-important and radiographic outcomes. Finally, we broadened our eligibility criteria to include bone healing in spinal fusions and tested the assumption regarding similarity of treatment effect using a formal test of interaction. The addition of this information suggests that electrical stimulation for bone healing may improve rates of radiographic union and produce modest but clinically significant improvements in pain relief.

Implications for clinical practice and research

A survey of 450 Canadian trauma surgeons in 2008 (response rate 79%) demonstrated that 23% of surgeons used electrical bone stimulators to accelerate bone healing68. Our findings support electrical stimulation as an adjunctive modality for radiographic bone healing and reduction in pain. Large trials of high methodological quality focusing on patient important outcomes are needed to establish the effectiveness of electrical stimulation on functional outcomes69.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that patients treated with electrical stimulation as an adjunct for bone healing have significantly less pain and experience lower rates of radiographic nonunion or persistent nonunion. No difference was seen with regards to functional outcomes in a limited number of trials. Future trials focusing on functional outcomes to identify appropriate indications and ideal patient selection are warranted.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Aleem, I. S. et al. Efficacy of Electrical Stimulators for Bone Healing: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Sham-Controlled Trials. Sci. Rep. 6, 31724; doi: 10.1038/srep31724 (2016).

References

Cook, J. J., Summers, N. J. & Cook, E. A. Healing in the new millennium: bone stimulators: an overview of where we’ve been and where we may be heading. Clinics in podiatric medicine and surgery 32, 45–59, 10.1016/j.cpm.2014.09.003 (2015).

Goldstein, C., Sprague, S. & Petrisor, B. A. Electrical stimulation for fracture healing: current evidence. Journal of orthopaedic trauma 24 Suppl 1, S62–S65, 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181cdde1b (2010).

Heckman, J. D. & Sarasohn-Kahn, J. The economics of treating tibia fractures. The cost of delayed unions. Bulletin (Hospital for Joint Diseases (New York, N.Y.)) 56, 63–72 (1997).

Busse, J. W. et al. Low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for fractures: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 338, b351, 10.1136/bmj.b351 (2009).

Anglen, J. The clinical use of bone stimulators. J South Orthop Assoc 12, 46–54 (2003).

Einhorn, T. A. Enhancement of fracture-healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77, 940–956 (1995).

Aaron, R. K., Boyan, B. D., Ciombor, D. M., Schwartz, Z. & Simon, B. J. Stimulation of growth factor synthesis by electric and electromagnetic fields. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 30–37 (2004).

Boden, S. D., Schimandle, J. H. & Hutton, W. C. An experimental lumbar intertransverse process spinal fusion model. Radiographic, histologic, and biomechanical healing characteristics. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20, 412–420 (1995).

Ciombor, D. M. & Aaron, R. K. The role of electrical stimulation in bone repair. Foot and ankle clinics 10, 579–593, vii, 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.06.006 (2005).

France, J. C., Norman, T. L., Santrock, R. D., McGrath, B. & Simon, B. J. The efficacy of direct current stimulation for lumbar intertransverse process fusions in an animal model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26, 1002–1008 (2001).

Haddad, J. B., Obolensky, A. G. & Shinnick, P. The biologic effects and the therapeutic mechanism of action of electric and electromagnetic field stimulation on bone and cartilage: new findings and a review of earlier work. J Altern Complement Med 13, 485–490, 10.1089/acm.2007.5270 (2007).

Akai, M. & Hayashi, K. Effect of electrical stimulation on musculoskeletal systems; a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Bioelectromagnetics 23, 132–143 (2002).

Akai, M., Kawashima, N., Kimura, T. & Hayashi, K. Electrical stimulation as an adjunct to spinal fusion: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Bioelectromagnetics 23, 496–504, 10.1002/bem.10041 (2002).

Ebrahim, S., Mollon, B., Bance, S., Busse, J. W. & Bhandari, M. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasonography versus electrical stimulation for fracture healing: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie 57, E105–E118 (2014).

Griffin Xavier, L., Costa Matthew, L., Parsons, Nick & Smith, Nick Electromagnetic field stimulation for treating delayed union or non-union of long bone fractures in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2011). < http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008471.pub2/abstract>.

Mollon, B., da Silva, V., Busse, J. W., Einhorn, T. A. & Bhandari, M. Electrical stimulation for long-bone fracture-healing: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery-American Volume 90, 2322–2330 (2008).

Park, P., Lau, D., Brodt, E. D. & Dettori, J. R. Electrical stimulation to enhance spinal fusion: a systematic review. Evidence-based spine-care journal 5, 87–94, 10.1055/s-0034-1386752 (2014).

Tian, N. F. et al. Efficacy of electrical stimulation for spinal fusion: a meta-analysis of fusion rate. Spine J 13, 1238–1243, 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.056 (2013).

Walker, N. A., Denegar, C. R. & Preische, J. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and pulsed electromagnetic field in the treatment of tibial fractures: a systematic review. Journal of athletic training 42, 530–535 (2007).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8, 336–341, 310.1016/j.ijsu.2010.1002.1007. Epub 2010 Feb 1018 (2010).

Higgins JPT, G. S. editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, 2011).

Kaptchuk, T. J., Goldman, P., Stone, D. A. & Stason, W. B. Do medical devices have enhanced placebo effects? Journal of clinical epidemiology 53, 786–792 (2000).

Bryant, D., Havey, T. C., Roberts, R. & Guyatt, G. How many patients? How many limbs? Analysis of patients or limbs in the orthopaedic literature: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88, 41–45, 10.2106/jbjs.e.00272 (2006).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence–study limitations (risk of bias). Journal of clinical epidemiology 64, 407–415, 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017 (2011).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

Musculoskeletal injuries report: incidence, risk factors and prevention. (Rosemont, IL).

Khan, S. N. et al. The biology of bone grafting. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 13, 77–86 (2005).

Marsell, R. & Einhorn, T. A. The biology of fracture healing. Injury 42, 551–555, 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031 (2011).

Day, S. M., Ostrum, R. F., Chao, E. Y. S., Rubin, C. T., Aro, H. T. & Einhorn, T.A. Orthopaedic basic science: biology and biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system. 2 edn, 371–399 (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2000).

Gotzsche, P. C. Why we need a broad perspective on meta-analysis. It may be crucially important for patients. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 321, 585–586 (2000).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled clinical trials 7, 177–188 (1986).

Murad, M. H., Montori, V. M., Walter, S. D. & Guyatt, G. H. Estimating risk difference from relative association measures in meta-analysis can infrequently pose interpretational challenges. Journal of clinical epidemiology 62, 865–867, 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.11.005 (2009).

Akl, E. A. et al. Using alternative statistical formats for presenting risks and risk reductions. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, Cd006776, 10.1002/14651858.CD006776.pub2 (2011).

Hozo, S. P., Djulbegovic, B. & Hozo, I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 5, 13, 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13 (2005).

Sun, X., Briel, M., Walter, S. D. & Guyatt, G. H. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 340, c117, 10.1136/bmj.c117 (2010).

Altman, D. G. & Bland, J. M. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 326, 219 (2003).

Akl, E. A. et al. Addressing dichotomous data for participants excluded from trial analysis: a guide for systematic reviewers. PloS one 8, e57132, 10.1371/journal.pone.0057132 (2013).

Johnston, B. C. et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine 157, 878–888 (2012).

Kuurstra, N., Vannabouathong, C., Sprague, S. & Bhandari, M. Guidelines for fracture healing assessments in clinical trials. Part II: electronic data capture and image management systems–Global Adjudicator system. Injury 42, 317–320, 10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.054 (2011).

McKee, M. D. Displaced fractures of the clavicle: who should be fixed? commentary on an article by C.M. Robinson, FRCSEd(Tr&Orth) et al.: “Open reduction and plate fixation versus nonoperative treatment for displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial”. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95, e1291–e1292, 10.2106/jbjs.m.00527 (2013).

Bhandari, M., Petrisor, B. & Schemitsch, E. Outcome measurements in orthopedic. Indian journal of orthopaedics 41, 32–36, 10.4103/0019-5413.30523 (2007).

Atkins, D. et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 328, 1490, 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 (2004).

Betti, E. M. S., Cadossi, R., Faldini, C. & Faldini, A. Effect of stimulation by low-frequency pulsed electromagnetic fields in subjects with fracture of the femoral neck. 853–855 (Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 1999).

Faldini, C., Cadossi, M., Luciani, D., Betti, E., Chiarello, E. & Giannini, S. Electromagnetic bone growth stimulation in patients with femoral neck fractures treated with screws: Prospective randomized double-blind study. Current Orthopaedic Practice 21, 282–287 (2010).

Andersen, T. et al. The effect of electrical stimulation on lumbar spinal fusion in older patients: a randomized, controlled, multi-center trial: part 2: fusion rates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34, 2248–2253, 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b02c59 (2009).

Andersen, T. et al. The effect of electrical stimulation on lumbar spinal fusion in older patients: a randomized, controlled, multi-center trial: part 1: functional outcome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34, 2241–2247, 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b02988 (2009).

Adie, S., Harris, I. A., Naylor, J. M., Rae, H., Dao, A., Yong, S. & Ying, V. Pulsed electromagnetic field stimulation for acute tibial shaft fractures: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery-American Volume 93, 1569–1576 (2011).

Barker, A. T., Dixon, R. A., Sharrard, W. J. W. & Sutcliffe, M. L. Pulsed magnetic field therapy for tibial non-union. Interim results of a double-blind trial. Lancet 1, 994–996 (1984).

Goodwin, C. B. et al. A double-blind study of capacitively coupled electrical stimulation as an adjunct to lumbar spinal fusions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 24, 1349–1356; discussion 1357 (1999).

Hannemann, P. F., Gottgens, K. W., van Wely, B. J., Kolkman, K. A., Werre, A. J., Poeze, M. & Brink, P. R. The clinical and radiological outcome of pulsed electromagnetic field treatment for acute scaphoid fractures: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery-British Volume 94, 1403–1408 (2012).

Hannemann, P. F., van Wezenbeek, M. R., Kolkman, K. A., Twiss, E. L., Berghmans, C. H., Dirven, P. A., Brink, P. R. & Poeze, M. CT scan-evaluated outcome of pulsed electromagnetic fields in the treatment of acute scaphoid fractures: a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Bone & Joint Journal 96-B, 1070–1076 (2014).

Linovitz, R. J. et al. Combined magnetic fields accelerate and increase spine fusion: a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27, 1383–1389; discussion 1389 (2002).

Mammi, G. I., Rocchi, R., Cadossi, R., Massari, L. & Traina, G. C. The electrical stimulation of tibial osteotomies. Double-blind study. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 246–253 (1993).

Martinez-Rondanelli, A., Martinez, J. P., Moncada, M. E., Manzi, E., Pinedo, C. R. & Cadavid, H. Electromagnetic stimulation as coadjuvant in the healing of diaphyseal femoral fractures: A randomized controlled trial. Colombia Medica 45, 67–71 (2014).

Mooney, V. A randomized double-blind prospective study of the efficacy of pulsed electromagnetic fields for interbody lumbar fusions. Spine 15, 708–712 (1990).

Scott, G. & King, J. B. A prospective, double-blind trial of electrical capacitive coupling in the treatment of non-union of long bones. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery-American Volume 76, 820–826 (1994).

Sharrard, W. J. A double-blind trial of pulsed electromagnetic fields for delayed union of tibial fractures. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery-British Volume 72, 347–355 (1990).

Shi, H. F., Xiong, J., Chen, Y. X., Wang, J. F., Qiu, X. S., Wang, Y. H. & Qiu, Y. Early application of pulsed electromagnetic field in the treatment of postoperative delayed union of long-bone fractures: a prospective randomized controlled study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 14, 35 (2013).

Simonis, R. B., Parnell, E. J., Ray, P. S. & Peacock, J. L. Electrical treatment of tibial non-union: a prospective, randomised, double-blind trial. Injury 34, 357–362 (2003).

Hannemann, P. F., Mommers, E. H., Schots, J. P., Brink, P. R. & Poeze, M. The effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and pulsed electromagnetic fields bone growth stimulation in acute fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 134, 1093–1106, 10.1007/s00402-014-2014-8 (2014).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence–imprecision. Journal of clinical epidemiology 64, 1283–1293, 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012 (2011).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence–inconsistency. Journal of clinical epidemiology 64, 1294–1302, 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017 (2011).

Jacquier, I., Boutron, I., Moher, D., Roy, C. & Ravaud, P. The reporting of randomized clinical trials using a surgical intervention is in need of immediate improvement: a systematic review. Ann Surg 244, 677–683, 10.1097/01.sla.0000242707.44007.80 (2006).

Poolman, R. W. et al. Does a “Level I Evidence” rating imply high quality of reporting in orthopaedic randomised controlled trials? BMC Med Res Methodol 6, 44, 10.1186/1471-2288-6-44 (2006).

Bannuru, R. R., Vaysbrot, E. E. & McIntyre, L. F. Did the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons osteoarthritis guidelines miss the mark? Arthroscopy 30, 86–89, 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.007 (2014).

Jaeschke, R., Singer, J. & Guyatt, G. H. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Controlled clinical trials 10, 407–415 (1989).

Busse, J. W. et al. Optimal Strategies for Reporting Pain in Clinical Trials and Systematic Reviews: Recommendations from an OMERACT 12 Workshop. J Rheumatol, 10.3899/jrheum.141440 (2015).

Busse, J. W., Morton, E., Lacchetti, C., Guyatt, G. H. & Bhandari, M. Current management of tibial shaft fractures: a survey of 450 Canadian orthopedic trauma surgeons. Acta orthopaedica 79, 689–694, 10.1080/17453670810016722 (2008).

Chan, S. & Bhandari, M. The quality of reporting of orthopaedic randomized trials with use of a checklist for nonpharmacological therapies. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89, 1970–1978, 10.2106/jbjs.f.01591 (2007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.S.A. and M.B. were involved in the study design and concept. I.S.A., I.A., N.E. and A.A. collected the data. I.S.A., I.A., N.E., J.W.B. and M.B. analyzed and interpreted the data. I.S.A., I.A., N.E. and M.B. drafted the initial manuscript. All authors made critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version. I.S.A. is the guarantor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MB has received honorariums from Smith & Nephew, Stryker, Amgen, Zimmer, Moximed, Bioventus, Merck, Eli Lilly, Sanofi and research grants from Smith & Nephew, DePuy, Eli Lily, Bioventus, Stryker, Zimmer, Amgen; JWB was a co-principal investigator for a recently completed trial of a competing device (low intensity pulsed ultrasound) that received funding from an industry sponsor (Smith & Nephew); no other relationships or activities have influenced the submitted work.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Aleem, I., Aleem, I., Evaniew, N. et al. Efficacy of Electrical Stimulators for Bone Healing: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Sham-Controlled Trials. Sci Rep 6, 31724 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31724

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31724

This article is cited by

-

Combined electric and magnetic field therapy for bone repair and regeneration: an investigation in a 3-mm and an augmented 17-mm tibia osteotomy model in sheep

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2023)

-

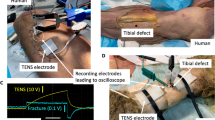

Efficacy of bone stimulators in large-animal models and humans may be limited by weak electric fields reaching fracture

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Recent advances in smart stimuli-responsive biomaterials for bone therapeutics and regeneration

Bone Research (2022)

-

Electrical stimulation in bone tissue engineering treatments

European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (2020)

-

Combining electrical stimulation and tissue engineering to treat large bone defects in a rat model

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.