Abstract

Hematite and goethite are the two most abundant iron oxides in natural environments. Their formation is controlled by multiple environmental factors; therefore, their relative concentration has been used widely to indicate climatic variations. In this study, we aimed to test whether hematite and goethite growth is influenced by ambient magnetic fields of Earth-like values. Ferrihydrite was aged at 95 °C in magnetic fields ranging from ~0 to ~100 μT. Our results indicate a large influence of the applied magnetic field on hematite and goethite growth from ferrihydrite. The synthesized products are a mixture of hematite and goethite for field intensities <~60 μT. Higher fields favour hematite formation by accelerating ferrimagnetic ferrihydrite aggregation. Additionally, hematite particles growing in a controlled magnetic field of ~100 μT appear to be arranged in chains, which may be reduced to magnetite keeping its original configuration, therefore, the presence of magnetic particles in chains in natural sediments cannot be used as an exclusive indicator of biogenic magnetite. Hematite vs. goethite formation in our experiments is influenced by field intensity values within the range of geomagnetic field variability. Thus, geomagnetic field intensity could be a source of variation when using iron (oxyhydr-)oxide concentrations in environmental magnetism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hematite and goethite are the two most abundant iron oxides in soils and sediments from many climatic zones; they are, however, generated in competition with each other1,2,3. Therefore, the ratio of these two minerals is often used to indicate climatic and environmental variation in soil records4,5 and in marine sediments6,7. Hematite and/or goethite growth from precursor ferrihydrite is controlled by many factors, such as temperature, pH, humidity, oxygen fugacity, and the presence of other ions in the system (e.g., Al and Si)8,9,10,11,12,13. Generally, warm and dry conditions favour hematite formation14,15, while more humid conditions favour goethite formation16,17. Neutral pH and temperatures >~90 °C induce hematite formation while acid or alkaline solutions at temperatures <~80 °C yield goethite17. Increasing temperature and Al content favours hematite formation while an alkaline solution with high pH favours goethite formation11. The presence of dissolved phosphate and/or silicate may retard hematite and goethite formation8,13. In addition, hematite crystallizes along the direction of an applied magnetic field and faithfully records that field direction18,19. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask whether growth of hematite and goethite is influenced by the ambient geomagnetic field, which undergoes considerable variation both spatially and temporally20,21. However, it is presently unknown whether magnetic fields with different, Earth-like, intensities exert control on magnetic mineral growth. The range of field intensities up to ~100 μT is relevant in this context.

Possible magnetic field control has been studied in relation to formation of magnetite22,23 and greigite (Fe3S4)24. The saturation magnetization (Ms), saturation remanent magnetization (Mr), and coercive force (Bc) are markedly higher for samples synthesized in strong applied magnetic fields (0.25 T in the cited experiments) than for samples synthesized in the much weaker geomagnetic field23. It was also found that chain-like magnetic particles can grow under the influence of an external magnetic field23. For magnetite, higher magnetic fields (~0.35 T) tend to result in formation of larger and more crystalline particles23. He et al.24 investigated the magnetic-field-induced phase-selective formation of ferrosulphide microrods for materials applications. This was done using a hydrothermal process, where ammonium iron sulphate hexahydrate and different sulphur precursors were dissolved in distilled water and stirred vigorously for 30 min, and then aged in the presence or absence of a magnetic field (45 mT) at 180 °C in a Teflon vessel with circular disk-shaped magnets at the top and bottom of a stainless steel autoclave. Pure greigite was produced in the 45 mT field, whereas a mixture of Fe3S4 and FeS2 was produced in the much weaker geomagnetic field. Therefore, these authors proposed that introduction of a strong magnetic field to the reaction system preferentially induced formation of a pure magnetic phase over a mixture with a paramagnetic phase24.

The magnetic fields used in previous studies were in the millitesla (mT) range, which is larger than typical geomagnetic field intensities. Also, these studies focused on strongly magnetic minerals with materials applications in mind. Thus, the cited results cannot be extrapolated directly to natural soil and sediment samples. In this study, we synthesized a series of hematite and goethite samples under a range of controlled Earth-like fields to investigate a possible field dependence of hematite and goethite formation.

Results

Structure and morphological properties

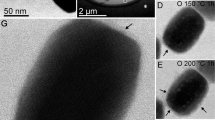

From X-ray diffractograms (Fig. 1), it is clear that the magnetic field strongly affects the transformation of ferrihydrite to hematite and goethite. For fields below ~60 μT, hematite and goethite coexist. In contrast, above 60 μT, hematite is dominant and goethite is undetectable. Based on XRD results, we infer that the rod-shaped particles in TEM observations (Fig. 2) are goethite, while the relatively small oblate grains are hematite. For growth fields <~60 μT, goethite is observed commonly with an axial length of up to 700 nm and width of up to 200 nm (Fig. 2a–d). Hematite grains with a particle size of ~300 nm are dispersed around goethite. When the applied field during synthesis exceeds ~100 μT, most hematite particles appear to be arranged in chains (Fig. 2f). The size of individual platelets is remarkably uniform at ~260 nm.

The red and blue lines represent the characteristic lattice reflections for hematite and goethite, respectively, where Hm and Gt stand for hematite and goethite respectively, and numbers between the brackets are Miller indices for respective reflections for goethite and hematite. Numbers in the sample labels represent the field intensity, e.g., F15.4 μT represents a sample synthesized in a 15.4 μT field.

Sample labelling is as in Fig. 1.

Magnetic Properties

The samples are not saturated magnetically even in a 5 T field (Figs 3 and 4a). The hysteresis loops before slope correction also become wider with increasing applied field during synthesis, and Bc and Mr values for the samples generally increase with increasing applied field during synthesis (Fig. 3). IRM@5T increases gradually from 6 × 10−2 to 19 × 10−2Am2/kg with increasing applied field during synthesis. IRM@5T for samples that grew in fields <~60 μT is smaller than the SIRM of typical hematite (~0.1 Am2kg−1), which may be attributed to goethite contamination and lower overall particle crystallinity, or to different synthesis conditions. IRM component analyses indicate the presence of two magnetic components, a relatively low coercivity (L) component (IRML) with a mean coercivity of around 100–300 mT, and a high coercivity (H) component (IRMH) with a mean coercivity of around 1 T (Fig. 4b–g, Table 1). Pure goethite (i.e., that lacks cation substitution) has large coercivities and cannot be saturated even in a 57 T field25. Therefore, the two identified coercivity components are attributed to hematites with different coercivities. Apparently, the IRM of these samples is dominated by IRMH, which contributes 82% to 95% of the IRM (Table 1). IRML may be attributed to fine particles that are also produced through the aging in solution. The IRM of these quasi-superparamagnetic particles is sensitive to the process of thermal activation which leads to a softer IRM component, IRML, next to the dominant IRMH26.

Bc values are indicated in green and orange, respectively. The left-hand ordinate axis refers to hysteresis loops before slope correction while the right-hand axis represents those after slope correction. Sample labelling is as in Fig. 1.

(a) IRM acquisition curves and DC demagnetization curves for samples grown in different applied fields. (b–g) IRM component analysis for hematite powder samples, where the red, blue, and pink lines indicate, respectively, the low coercivity component (IRML), high coercivity component (IRMH), and the sum of the two components (IRML + IRMH). Open circles represent the measured data.

FORC distributions for all of the synthesized samples are elongated with closed contours, which are indicative of stable single domain (SD) particles (Fig. 5)27,28. For samples F0 μT and F29.1 μT, the interaction field is ~50 mT, which is determined from the full width of the FORC distribution at half of its peak value. However, as the applied field during synthesis increases, the vertical spread of the FORC distribution becomes narrower and stabilizes at ~40 mT. Goethite is not detected in the FORC diagrams because of its large coercivity (>1 T). Significant magnetostatic interactions tend not to be important in natural and some synthetic goethite and hematite samples because the weak spontaneous magnetization of these minerals makes them less susceptible to strong interactions29. The interaction field distributions evident in Fig. 5 are, therefore, a likely consequence of the close packing of magnetic particles in our measurements.

Hysteresis parameters for our samples are summarized in Fig. 6. Bcr decreases with increasing applied field during synthesis (Fig. 6a). In contrast, Mr increases with field in a quasi-linear trend (Fig. 6b). The median coercivity (B1/2) of IRMH is denoted by B1/2H, which decreases linearly with increasing field applied during synthesis in accord with Bcr (Fig. 6c). This further indicates that IRMH is the dominant component at higher applied fields during synthesis. Hm/(Hm + Gt) calculated from XRD data increases with applied field during synthesis up to ~60 μT, and reaches ~100% when applied fields during synthesis are >~60 μT (Fig. 6d). This demonstrates that the hematite content increases with increasing applied field during synthesis.

(a) Coercivity of remanence (Bcr) vs. applied field; (b) saturation remanent magnetization (Mr) vs. applied field; (c) B1/2 of IRMH (B1/2H) vs. applied field; (d) Hm/(Hm + Gt), calculated from XRD data, vs. applied field. In each subfigure, the applied field is the magnetic field in which each synthesis was performed.

Discussion

Control mechanism of Earth-like fields on hematite/goethite formation

A fair number of synthesis pathways have been proposed for hematite and goethite formation, such as hydrolysis of acid solutions of Fe(III) salts, transformation of ferrihydrite, oxidative hydrolysis of Fe(II) salts, the gel-sol method, and several others8,9,10,11,12,30. Formation reactions of goethite and hematite from precursor ferrihydrite suspension are different. Goethite forms by precipitation from solution after ferrihydrite dissolution, while hematite formation is preceded by ferrihydrite aggregation and hematite nucleation within these aggregates as a solid phase reaction8,10. However, it is proposed recently that goethite rods can be formed from ferrihydrite through phase transformation followed by oriented aggregation31,32, where ferrihydrite suspension has been dialyzed against Milli-Q water to remove the solvent and/or surface molecules, which favours an irreversibly oriented aggregate formation32. However, in natural environments, it is difficult to remove the solvent. Given that ferrihydrite suspension to hematite or goethite pathway is so prominent in natural environments1,2, we, therefore, primarily focus on the influence of magnetic fields on the final product synthesized via this route.

In general, higher or lower pH and lower temperature (<80 °C) favour goethite formation while neutral pH and higher temperature (>90 °C) favour hematite formation since dissolution of ferrihydrite is retarded at neutral pH10,17. In our experiments, NaHCO3 was added to bring pH to ~7 at room temperature and aging temperature was fixed at 95 °C to inhibit goethite formation. The actual pH at 95 °C is not easy to measure, but it will be the same for all samples. However, substantial goethite still formed at 95 °C, where its concentration decreased with increasing applied field during synthesis (Figs 1,2 and 6). This demonstrates that the applied field strength during synthesis plays a significant role in the formation of these two minerals, even in weak Earth-like fields.

Based on our results and the different formation mechanisms of hematite and goethite, we infer that an applied magnetic field should favour ferrihydrite aggregation. To test this inference, we synthesized a sample under the same conditions as sample F104.4 μT, but stirred the suspension for 5 minutes at 5-hour intervals with a glass stick to disturb ferrihydrite particle aggregation. This sample is labeled ‘F104.4 μT-agitation’. XRD results indicate that the final product is a mixture of hematite and goethite (Fig. 7a). This means that, although aging took place in a magnetic field of ~100 μT, the preference for hematite formation was disturbed by the agitation. Therefore, we propose a model in which ferrihydrite can aggregate or dissolve depending on the solution conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, etc.). Without an applied field (Fig. 7b), hematite and goethite form simultaneously (apparently the two formation mechanisms compete). However, if a magnetic field is applied above a certain threshold value, ferrimagnetic ferrihydrite, which is an intermediate transformation product in the reaction from ferrihydrite to hematite33, can aggregate parallel to the field direction (Fig. 7c) and hematite will form preferentially. Even in a relatively high applied field, this aggregation can be disrupted by intermittent agitation (Fig. 7d); then both hematite and goethite are produced (Fig. 7a). The suggested mechanism is a preliminary hypothesis. Recently, it is proposed that goethite rods can be formed from ferrihydrite through phase transformation followed by oriented aggregation31,32, but magnetic field effect was not involved. So no other studies exist along these lines, more explicit explanations for the apparent control of an ambient magnetic field on magnetic mineral formation are needed, including further experimentation and molecular dynamics calculations34,35.

(a) X-Ray diffractograms of samples grown in a ~0 μT field, and a 104.4 μT field with and without agitation; (b–d) the model proposed for ferrihydrite aging (b) without an applied field, (c) in an applied field and (d) with agitation in an applied field, where the orange circles with arrows represent ferrimagnetic ferrihydrite particles, and the arrows above the cylinders indicate the applied field direction.

Geological significance

Transformation of ferrihydrite to hematite or goethite in soil solutions is controlled by various environmental factors (pH, water activity, temperature, surface poisoners, etc.)8,9,10,11,12,13,36. For example, Torrent and Guzmán11 reported that hematite is favoured over goethite by decreasing water activity. Furthermore, they reported that higher ionic strength, i.e., a more concentrated solution, also influences the transformation pathway, e.g., calcium and magnesium favour hematite over goethite. Thus, hematite can form and will be favoured over goethite in natural environments with low water activity, for instance dry or saline soils or sediments37,38. In addition, mobile Al in the form of Al3+, Al(OH)2+ or Al(OH)2+, and Si in the form of H4SiO4 in the solution may also promote hematite formation by reducing ferrihydrite solubility, which in turn favours the internal hematite crystallization mechanism over the via-solution mechanism required for goethite crystallization2,39. However, it is evident from our results that hematite and goethite concentration is controlled not only by environmental factors but also by applied field strength. Mr increases with applied field strength during synthesis (Figs 3,4a and 6b,c), which may be caused by varying hematite and goethite contents that formed in competition. In addition, the relative hematite content (Hm/(Hm + Gt)) increases with applied field strength (Fig. 6d). Thus, geomagnetic field intensity variations could play an important role in the selective formation of iron oxides, which has been largely overlooked until now.

For a dipole field, the field intensity at the poles is twice that at the equator. Typical Earth-like values are ~30 μT at the equator and ~60 μT at the poles40,41. The minimum intensity of the present-day geomagnetic field, which occurs within the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly region, is ~22 μT while the highest field intensity is ~64 μT in Siberia and in the Southern Ocean and Antarctica south of Australia40. In addition, non-transitional paleointensities over the past 300 Ma typically range from ~20 to ~80 μT21,42. Therefore, geomagnetic intensity influence on iron oxide formation could be a source of variation when using magnetic concentration proxies to investigate climate variations on long time scales or spatial scales, e.g., studies of dry versus humid variability on the Chinese Loess Plateau4,5, paleoclimatic studies of marine sediments7,8, or spatial variations of hematite and goethite contents14.

Indicators for identification of biogenic magnetite

Biogenic magnetic minerals (i.e., magnetite or greigite magnetosomes) have widespread occurrence in natural environments and make significant contributions to the paleomagnetic and paleoenvironmental record of sediments, because of their stable SD remanence and sensitivity to geochemical conditions that control their growth and preservation43,44,45. Discrimination of these biogenic magnetic minerals is important for environmental interpretations, especially in relation to assessing records of ancient magnetosome occurrences46. Such magnetofossils have distinct crystal morphologies, narrow particle size distributions, and chain structures; thus, criteria have been developed to identify their presence based on these features29,44,46,47,48,49. TEM observation of aligned magnetite crystals in chains and their general cuboidal shape are interpreted to indicate a bacterial origin44,47. Magnetic techniques for magnetofossil detection are rapid and nondestructive, and include low temperature magnetism50,51, coercivity analysis of IRM acquisition curves52, and FORC diagrams and ferromagnetic resonance spectroscopy (FMR)29,44,47,48,49. Magnetosome chain structures produce FMR spectra with multiple derivative maxima, asymmetry (A) <1 and an effective g-factor (geff) <2.1244,47,48. FORC analysis provides an excellent tool for isolating the biogenic component as a ‘central ridge’ signature with a peak in the switching field distribution between ~20 and 60 mT29,44,49.

Our results indicate that hematite synthesized in a magnetic field of ~100 μT can also have chain-like arrangements with unique particle size of around 260 nm. If these samples were preserved in short-lived periods with reducing conditions, they may be reduced to magnetite but inherit the same shape. For example, in the presence of iron-reducing bacteria and organic matter, hematite in well-drained soils can be transformed to magnetite through fermentation53,54 or be reduced to magnetite during burning and maintain its morphology, as discussed by Jiang et al.55. This kind of abiotic chain-like magnetite may confuse magnetofossil identification, and would lead to erroneous paleoenvironmental interpretation56. Thus, attention should be paid to this aspect when assessing probable records of biogenic magnetic minerals.

To summarize, our results indicate that Earth-like magnetic fields affect hematite and goethite growth. Aging of ferrihydrite at 95 °C yields as the final synthesis product a mixture of hematite and goethite for field intensities <~60 μT. The hematite content increases with increasing applied field during synthesis at the expense of the goethite content. Higher fields favour hematite formation, which is illustrated by decreased Bcr and increased Mr values. Hematite formation from ferrihydrite is a solid-phase reaction, while goethite is precipitated from solution after ferrihydrite dissolution. Magnetic fields are interpreted to accelerate ferrihydrite aggregation via a ferrimagnetic intermediate phase. This implies that the effect of geomagnetic field intensity variations on iron oxide formation could be relevant when evaluating the climatic significance of their concentration variations, e.g., in loess/paleosol sequences. Furthermore, hematite particles grown in magnetic fields of ~100 μT appear to be arranged in chains with individual particles having a unique size of around 260 nm. Chain-like magnetic particle arrangements cannot, therefore, be used as an exclusive indicator of biogenic magnetofossils.

Methods

Sample preparations

Fourteen samples starting from pure ferrihydrite (Fe8.2O8.5(OH)7.4) were prepared under similar conditions. Ferrihydrite was synthesized by mixing 100 mL of 0.5 M Fe(NO3)3 and 100 mL of 2 M NaOH at room temperature. Subsequently 50 mL of 1 M NaHCO3 was added to bring the pH to ~7 at room temperature. The deionized water used for the solutions was heated to 95 °C in advance to inhibit goethite formation. The ferrihydrite was aged under controlled temperature and field conditions. The temperature of the suspensions was maintained at 95 ± 3 °C in a small furnace equipped with a digital thermometer. A controlled magnetic field was obtained with two sets of cubic Helmholtz coils (1 metre × 1 metre), which were aligned with the declination of the ambient laboratory field. One pair of coils was set horizontally to produce the vertical field component, while the other pair was set vertically to produce the horizontal component. The fields were set to ~0 (which probably deviated from 0 μT but not by more than 100–200 nT), 15.4, 29.1, 43.6, 58.8, 73.2, and 104.4 μT, respectively. The samples are labeled with their growth field intensities as F0 μT, F0 μTb, F15.4 μT, F15.4 μTb, F29.1 μT, F29.1 μTb, F43.6 μT, F43.6 μTb, F58.8 μT, F58.8 μTb, F73.2 μT, F73.2 μTb, F104.4 μT, and F104.4 μTb, where sample labels ending with ‘b’ are replicate samples and ‘F’ is the abbreviation for ‘field’. In order to determine when the reaction was completed, 10 mL of suspension was extracted every five hours to measure magnetic susceptibility variations in a trial experiment as described by Jiang et al.19. After aging, samples were washed free of salts by centrifuging the suspension with deionized water until the electrical conductivity of the equilibrium solution became <0.01 dS/m (dS/m: 10−2 Siemens per meter). Finally, the samples were dried in an oven at 40 °C.

XRD and TEM analysis

Sample purity was verified with powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a D/MAX-2400XRD instrument with monochromatic CuΚα radiation, a scan step size of 0.017° 2θ, and a scan step time of 1 s. The receiving slit size was 0.1 mm. Semi-quantitative values for hematite and goethite proportions within samples were calculated from XRD data based on a standard curve for hematite and goethite mixtures, which was calibrated from the area underneath the diffraction peaks from several mixtures with known hematite and goethite contents57. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were obtained with a JEM-2010 microscope operating at 100 kV to examine particle morphology and possible grain size variation as a function of applied field during sample synthesis.

Magnetic measurements

Both acquisition curves of the isothermal remanent magnetization (IRM) and back-field curves with 80 steps that were logarithmically distributed over the field range were measured with a Quantum Design Magnetic Properties Measurement System (MPMS XL-5, with a sensitivity of 5.0 × 10−10 Am2). A maximum field of 5 T was applied to determine the coercivity of remanence (Bcr) at room temperature. The IRM acquired at 5 T is labeled as IRM@5T. IRM acquisition curves were decomposed into magnetic coercivity components following the method of Kruiver et al.58 in which it is assumed that the IRM acquisition curves are a linear sum of components represented by cumulative log-Gaussian functions. Subsequently, hysteresis loops for all samples were measured at room temperature using a MPMS XL-5 system with a maximum field of 5 T with 190 field steps. Bc, Ms, and Mr were calculated from the loops. First-order reversal curve (FORC) diagrams59 were acquired using a Princeton Measurements Corporation vibrating sample magnetometer (Micromag VSM 3900) at room temperature. A total of 180 FORCs were measured with saturation field up to 2 T and a field increment of 10.2 mT. FORC diagrams were processed using the FORCinel version 1.18 software60 with smoothing factor of 7.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Jiang, Z. et al. Control of Earth-like magnetic fields on the transformation of ferrihydrite to hematite and goethite. Sci. Rep. 6, 30395; doi: 10.1038/srep30395 (2016).

References

Schwertmann, U. Occurrence and formation of iron oxides in various pedoenvironments, In Iron in Soils and Clay Minerals ( Stucki, J. W. et al. eds). Springer. pp. 267‒308 (1988).

Cornell, R. & Schwertmann, U. The Iron Oxides: Structure, Properties, Reactions, Occurrences and Uses. John Wiley & Sons, Darmstadt, Germany (2003).

Liu, Q. S. et al. Environmental magnetism: Principles and applications. Rev. Geophys. 50, RG4002, doi: 10.1029/2012RG000393 (2012).

Balsam, W., Ji, J. & Chen, J. Climatic interpretation of the Luochuan and Lingtai loess sections, China, based on changing iron oxide mineralogy and magnetic susceptibility. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 223, 335‒348 (2004).

Ji, J. et al. High resolution hematite/goethite records from Chinese loess sequences for the last glacial-interglacial cycle: rapid climatic response of the East Asian Monsoon to the tropical Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L03207, doi: 10.1029/2003GL018975 (2004).

Zhang, Y. G. et al. High resolution hematite and goethite records from ODP 1143, South China Sea: co-evolution of monsoonal precipitation and El Nino over the past 600,000 years. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 264, 136‒150 (2007).

Abrajevitch, A., Van der Voo, R. & Rea, D. K. Variations in relative abundances of goethite and hematite in Bengal Fan sediments: climatic vs. diagenetic signals. Mar. Geol. 267, 191‒206 (2009).

Cornell, R., Giovanoli, R. & Schindler, P. Effect of silicate species on the transformation of ferrihydrite into goethite and hematite in alkaline media. Clays Clay Miner. 35, 21‒28 (1987).

Cornell, R. & Schneider, W. Formation of goethite from ferrihydrite at physiological pH under the influence of cysteine. Polyhedron 8, 149‒155 (1989).

Lewis, D. & Schwertmann, U. The influence of aluminum on the formation of iron oxides. IV. The influence of [A1], [OH], and temperature. Clays Clay Miner. 27, 195–200 (1979).

Torrent, J. & Guzmán, R. Crystallization of Fe (III)-oxides from ferrihydrite in salt solutions: osmotic and specific ion effects. Clay Miner. 17, 463‒469 (1982).

Schwertmann, U. & Murad, E. Effect of pH on the formation of goethite and hematite from ferrihydrite. Clays Clay Miner. 31, 277‒284 (1983).

Gálvez, N., Barrón, V. & Torrent, J. Effect of phosphate on the crystallization of hematite, goethite, and lepidocrocite from ferrihydrite. Clays Clay Miner. 47, 304‒311 (1999).

Kämpf, N. & Schwertmann, U. Goethite and hematite in a climosequence in southern Brazil and their application in classification of kaolinitic soils. Geoderma 29, 27‒39 (1983).

Maher, B. A. Characterisation of soils by mineral magnetic measurements. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 42, 76‒92 (1986).

Balsam, W. L., Otto-Bliesner, B. L. & Deaton, B. C. Modern and last glacial maximum eolian sedimentation patterns in the Atlantic Ocean interpreted from sediment iron oxide content. Paleoceanography 10, 493‒507 (1995).

Schwertmann, U. & Cornell, R. M. Iron Oxides in the Laboratory. Weinheim, Wiley-VCH (2000).

Stokking, L. B. & Tauxe, L. Acquisition of chemical remanent magnetization by synthetic iron oxide. Nature 327, 610‒612 (1987).

Jiang, Z. et al. Acquisition of chemical remanent magnetization during experimental ferrihydrite–hematite conversion in Earth-like magnetic field‒implications for paleomagnetic studies of red beds. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 428, 1‒10 (2015).

Valet, J. P., Meynadier, L. & Guyodo, Y. Geomagnetic dipole strength and reversal rate over the past two million years. Nature 435, 802‒805 (2005).

Biggin, A. J. et al. Possible links between long-term geomagnetic variations and whole-mantle convection processes. Nature Geosci. 5, 526‒533 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. Magnetic properties improvement in Fe3O4 nanoparticles grown under magnetic fields. J. Cryst. Growth 266, 500‒504 (2004).

Wu, M. et al. Magnetic field-assisted hydrothermal growth of chain-like nanostructure of magnetite. Chem. Phys. Lett. 401, 374‒379 (2005).

He, Z. et al. Magnetic-field-induced phase-selective synthesis of ferrosulfide microrods by a hydrothermal process: microstructure control and magnetic properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 16, 1105‒1111 (2006).

Rochette, P. et al. Non-saturation of the defect moment of goethite and fine-grained hematite up to 57 Teslas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L22309, doi: 10.1029/2005GL024196 (2005).

Heslop, D., McIntosh, G. & Dekkers, M. J. Using time- and temperature-dependent Preisach models to investigate the limitations of modelling isothermal remanent magnetization acquisition curves with cumulative log Gaussian functions. Geophys. J. Int. 157, 55‒63 (2004).

Egli, R. et al. Detection of noninteracting single domain particles using first-order reversal curve diagrams. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, Q01Z11, doi: 10.1029/2009GC002916 (2010).

Roberts, A. P. et al. Understanding fine magnetic particle systems through use of first-order reversal curve diagrams. Rev. Geophys. 52, 557‒602, doi: 10.1002/2014RG000462 (2014).

Roberts, A. P. et al. Characterization of hematite (α-Fe2O3), goethite (α-FeOOH), greigite (Fe3S4), and pyrrhotite (Fe7S8) using first-order reversal curve diagrams. J.Geophys. Res. 111, B12S35, doi: 10.1029/2006JB004715 (2006).

Schwertmann, U. & Cornell, R. M. Iron Oxides In The Laboratory, Weinheim, Wiley-VCH (2000).

Guyodo, Y. et al. From nanodots to nanorods: Oriented aggregation and magnetic evolution of nanocrystalline goethite. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1512, doi: 1510.1029/2003GL017021 (2003).

Burleson, D. J. & Penn, R. L. Two-step growth of goethite from ferrihydrite. Langmuir 22, 402‒409 (2006).

Michel, F. M. et al. Ordered ferrimagnetic form of ferrihydrite reveals links among structure, composition, and magnetism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2787‒2792 (2010).

Rustad, J. R. & Felmy, A. R. The influence of edge sites on the development of surface charge on goethite nanoparticles: a molecular dynamics investigation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 1405–1411 (2005).

Chicot, D. et al. Mechanical properties of magnetite (Fe3O4), hematite (α-Fe2O3) and goethite (α-FeOOH) by instrumented indentation and molecular dynamics analysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 129, 862–870 (2011).

Till, J. et al. Goethite as a potential source of magnetic nanoparticles in sediments. Geology 43, 75–78 (2015).

Walker, T. R. Red color in dune sand. A study of global sand seas: US Geol. Surv. Prof. Pap. 1052, 61–81 (1979).

Gardner, R. A. Reddening of dune sands—evidence from southeast India. Earth Surf. Proc. Landf. 6, 459‒468 (1981).

Schwertmann, U., Friedl, J. & Stanjek, H. From Fe (III) ions to ferrihydrite and then to hematite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 209, 215–223 (1999).

Finlay, C. et al. International geomagnetic reference field: the eleventh generation. Geophys. J. Int. 183, 1216–1230 (2010).

Thébault, E. et al. International geomagnetic reference field: the 12th generation. Earth Planets Space 67, doi: 10.1186/s40623-015-0228-9 (2015).

Tanaka, H., Kono, M. & Uchimura, H. Some global features of palaeointensity in geological time. Geophys. J. Int. 120, 97–102 (1995).

Stolz, J. F., Chang, S.-B. R. & Kirschvink, J. L. Biogenic magnetite in stromatolites. I. Occurrence in modern sedimentary environments. Precambrian Res. 43, 295–304 (1989).

Roberts, A. P. et al. Searching for single domain magnetite in the ‘pseudo-single-domain’ sedimentary haystack: implications of biogenic magnetite preservation for sediment magnetism and relative paleointensity determinations. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B08104, doi: 10.1029/2012JB009412 (2012).

Reinholdsson, M. et al. Magnetic enhancement of Baltic Sea sapropels by greigite magnetofossils. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 366, 137–150 (2013).

Chang, S.-B. R. et al. Biogenic magnetite in stromatolites. II. Occurrence in ancient sedimentary environments. Precambrian Res. 43, 305–315 (1989).

Kopp, R. E. & Kirschvink, J. L. The identification and biogeochemical interpretation of fossil magnetotactic bacteria. Earth-Sci. Rev. 86, 42–61 (2008).

Gehring, A. U. et al. The detection of magnetotactic bacteria and magnetofossils by means of magnetic anisotropy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 309, 113–117 (2011).

Heslop, D., Roberts, A. P. & Chang, L. Characterizing magnetofossils from first-order reversal curve (FORC) central ridge signatures. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 15, 2170–2179 (2014).

Moskowitz, B. M., Frankel, R. B. & Bazylinski, D. A. Rock magnetic criteria for the detection of biogenic magnetite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 120, 283–300 (1993).

Chang, L. et al. Discrimination of biogenic and detrital magnetite through a double Verwey transition temperature. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 3–14, doi: 10.1002/2015JB012485 (2016).

Egli, R. Characterization of individual rock magnetic components by analysis of remanence curves. 3. Bacterial magnetite and natural processes in lakes. Phys. Chem. Earth 29, 869–884 (2004).

Mullins, C. E. Magnetic susceptibility of the soil and its significance in soil science–a review. J. Soil Sci. 28, 223–246 (1977).

Maher, B. A. Magnetic properties of modern soils and Quaternary loessic paleosols: paleoclimatic implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 137, 25–54 (1998).

Jiang, Z. et al. Magnetism of Al-substituted magnetite reduced from Al-hematite. J. Geophys. Res. 121, doi: 10.1002/2016JB012863 (2016).

Maher, B. A. & Taylor, R. M. Formation of ultrafine‒grained magnetite in soils. Nature 336, 368–370 (1988).

Cabello, E. Magnetic properties of iron oxides in Mediteranean soils, Universidad de Córdoba. pp. 179 (2008).

Kruiver, P. P., Dekkers, M. J. & Heslop, D. Quantification of magnetic coercivity components by the analysis of acquisition curves of isothermal remanent magnetisation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 189, 269–276 (2001).

Pike, C. R., Roberts, A. P. & Verosub, K. L. Characterizing interactions in fine magnetic particle systems using first order reversal curves. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 6660–6667 (1999).

Harrison, R. J. & Feinberg, J. M. FORCinel: an improved algorithm for calculating first-order reversal curve distributions using locally weighted regression smoothing. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q05016, doi: 10.1029/2008GC001987 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Lisa Tauxe, Prof. Michelle Coote and Dr. Huafeng Qin for useful discussions about this work. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 41504055, 41430962, 41374073, and 41025013). Z.X.J. further acknowledges support from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation. A.P.R. acknowledges support from the Australian Research Council (grants DP110105419 and DP120103952). We thank Prof. Yongjae Yu and an anonymous reviewer for comments that helped to improve this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J. and Q.L. designed the study. Z.J. prepared the samples and performed the measurements. Z.J., Q.L., M.J.D., V.B., J.T. and A.P.R. wrote the paper. All authors contributed to data interpretation and provided significant input to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Z., Liu, Q., Dekkers, M. et al. Control of Earth-like magnetic fields on the transformation of ferrihydrite to hematite and goethite. Sci Rep 6, 30395 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30395

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30395

This article is cited by

-

Electroactivity of the magnetotactic bacteria Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 and Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense MSR-1

Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering (2024)

-

Formation of iron oxide nanoparticles for the photooxidation of water: Alteration of finite size effects from ferrihydrite to hematite

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.