Abstract

We demonstrate the high structural and optical properties of InxGa1−xN epilayers (0 ≤ x ≤ 23) grown on conductive and transparent ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrates using a low-temperature GaN buffer layer rather than AlN buffer layer, which enhances the quality and stability of the crystals compared to those grown on (100)-oriented β-Ga2O3. Raman maps show that the 2″ wafer is relaxed and uniform. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) reveals that the dislocation density reduces considerably (~4.8 × 107 cm−2) at the grain centers. High-resolution TEM analysis demonstrates that most dislocations emerge at an angle with respect to the c-axis, whereas dislocations of the opposite phase form a loop and annihilate each other. The dislocation behavior is due to irregular (

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrates using a low-temperature GaN buffer layer rather than AlN buffer layer, which enhances the quality and stability of the crystals compared to those grown on (100)-oriented β-Ga2O3. Raman maps show that the 2″ wafer is relaxed and uniform. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) reveals that the dislocation density reduces considerably (~4.8 × 107 cm−2) at the grain centers. High-resolution TEM analysis demonstrates that most dislocations emerge at an angle with respect to the c-axis, whereas dislocations of the opposite phase form a loop and annihilate each other. The dislocation behavior is due to irregular ( 01) β-Ga2O3 surface at the interface and distorted buffer layer, followed by relaxed GaN epilayer. Photoluminescence results confirm high optical quality and time-resolved spectroscopy shows that the recombination is governed by bound excitons. We find that a low root-mean-square average (≤1.5 nm) of InxGa1−xN epilayers can be achieved with high optical quality of InxGa1−xN epilayers. We reveal that (

01) β-Ga2O3 surface at the interface and distorted buffer layer, followed by relaxed GaN epilayer. Photoluminescence results confirm high optical quality and time-resolved spectroscopy shows that the recombination is governed by bound excitons. We find that a low root-mean-square average (≤1.5 nm) of InxGa1−xN epilayers can be achieved with high optical quality of InxGa1−xN epilayers. We reveal that ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate has a strong potential for use in large-scale high-quality vertical light emitting device design.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate has a strong potential for use in large-scale high-quality vertical light emitting device design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wide bandgap III-nitride semiconductors have several material properties that make them attractive for potential application to devices that emit and detect light in the spectrum between ultraviolet (UV) and visible light and for high-power electronic devices1,2,3. Therefore, both research and industry are motivated to produce high-performing III-nitride devices. However, the high cost of native substrates is one of the key challenges to overcome in the field and commonly used substrates (sapphire (Al2O3), SiC, or Si) add complexity and cost to the device fabrication. Particularly, III-nitride based vertical devices, such as vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs), are costly and challenging to produce, thus compromising on the efficiency obtained. For example, the efficiency of devices grown on Al2O3 is threatened by the introduction of high threading dislocation density (TDD)4,5 due to a large lattice mismatch (14%) and a large difference in thermal expansion coefficients between III-nitride semiconductor and the substrate6,7. This high TDD causes many nonradiative recombinations and scattering centers, which will deteriorate the optical and electrical quality of III-nitride devices8. To date, several attempts have been made to increase the quantum efficiency, albeit with limited success. For example, although threading dislocations (TDs) ending with V-shaped defects in InGaN/GaN light-emitting diodes (LEDs) help to reduce the nonradiative recombination inside TDs, the total effective area contributing to the emission is still reduced9. Furthermore, high TDD leads to efficiency decline in AlGaN/GaN UV LEDs10. Therefore, low TDD is preferable, as it can improve the continuous operation lifetime for devices and high quantum efficiency8. Moreover, as Al2O3 substrates are insulating, the contacts should be established at the top surface of the devices. This not only reduces the total available light emission area but also increases the fabrication process complexity, in addition to requiring specialized packaging and integration of devices. Moreover, LEDs grown on Al2O3 exhibit current crowding due to lateral injection, which leads to poor current management and heat distribution, undermining device efficiency. For devices grown on SiC, micropipes are introduced during crystal growth, preventing the use of full wafers. In addition, SiC is very expensive and the incorporation of N2 dopants diminishes its transparency11. Even though this substrate is characterized by a smaller lattice mismatch (3.1%)12 compared to Al2O3 and provides vertical current injection geometry, the lack of the transparency of this conductive SiC decreases the LED efficiency due to the substrate light absorption. Therefore, as additional processing steps are required, the device fabrication is made more complex. Efforts are being made to enhance the light efficiency of LEDs on SiC by using substrate transferring technique (substrate liftoff or introduction of distributed Bragg reflectors (DBRs) between the nitride and the substrate to reflect the light back from the substrate are employed)13. Nonetheless, producing good quality nitride DBRs remains a challenge. Therefore, there is still a significant need for alternative substrates that can be employed in the fabrication of bright vertical light-emitting devices with good lattice match, high thermal and electrical conductivity and high transparency in UV spectral regions.

The β-Ga2O3 substrate combines the beneficial properties (low lattice mismatch, transparency and conductivity) of both Al2O3 and SiC. β-Ga2O3 is a promising candidate as a wide bandgap (4.8 eV)14 substrate for fabricating tunable bright III-nitride vertical light-emitting devices because it satisfies these conditions and surpasses several other substrates. Conducting β-Ga2O3 allows vertical current flow, reduces the forward operating voltage and series resistance and improves current distribution and thermal management. Conductive substrates allow fabricating the contacts at both the top and the bottom surface, which simplifies device fabrication, integration process and packaging. This approach also reduces the fabrication cost and increases the number of devices in a single chip, resulting in greater light extraction efficiency (LEE) compared to Al2O3 substrates. Furthermore, the transparent nature of β-Ga2O3 as a substrate provides a wider light-emitting area than do conductive SiC and Si substrates. Therefore, emission from vertical devices grown on β-Ga2O3 is omnidirectional, which further increases the LEE, resulting in a bright-light-emitting device and supporting high power operations. Conversely, emission from that grown on SiC is permitted through the top side only. In addition, Ga2O3 shows high stability at high growth temperatures of around 1100 °C15. Relative to GaN substrates, Ga2O3 has a wider bandgap and is cheaper to grow and process.

Previous attempts to grow high-quality III-nitride quantum-well-based (100)-oriented β-Ga2O3 have been unsuccessful, as the quality of these crystals is inadequate for high-performance devices16,17,18. The strong cleavage nature of the (100)-plane caused the GaN epilayer to detach and peel off from the (100) β-Ga2O3 plane19, causing complications to the required step of separating wafers by dicing. In our previous study, we found that using monoclinic ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate led to a high optical and structural quality GaN material using an AlN buffer layer20. Using this (

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate led to a high optical and structural quality GaN material using an AlN buffer layer20. Using this ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate, we found that (0002) GaN rocking curve (RC) has a significantly enhanced full width at half maximum (FWHM) value (430 arcsec)20 compared to that grown on (100)-oriented β-Ga2O3 (1200 arcsec)21. We reported a relatively low lattice mismatch of ~4.7% and an in-plane epitaxial orientation relationship of (010) β-Ga2O3 || (11

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate, we found that (0002) GaN rocking curve (RC) has a significantly enhanced full width at half maximum (FWHM) value (430 arcsec)20 compared to that grown on (100)-oriented β-Ga2O3 (1200 arcsec)21. We reported a relatively low lattice mismatch of ~4.7% and an in-plane epitaxial orientation relationship of (010) β-Ga2O3 || (11 0) GaN and (

0) GaN and ( 01) β-Ga2O3 || (0001) GaN20. The growth of InGaN LEDs on (

01) β-Ga2O3 || (0001) GaN20. The growth of InGaN LEDs on ( 01) β-Ga2O3 with an AlN buffer layer is presently under investigation22.

01) β-Ga2O3 with an AlN buffer layer is presently under investigation22.

In this paper, we demonstrate high optical and structural quality of Si-doped GaN and InxGa1−xN epilayers grown on ( 01) β-Ga2O3 substrate using a low-temperature GaN buffer layer by metal organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). Our results are a testament to the potential for producing InGaN vertical LEDs that are more efficient, of better quality and more simply and cheaply produced than LEDs grown on Al2O3 or SiC.

01) β-Ga2O3 substrate using a low-temperature GaN buffer layer by metal organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). Our results are a testament to the potential for producing InGaN vertical LEDs that are more efficient, of better quality and more simply and cheaply produced than LEDs grown on Al2O3 or SiC.

Growth and Characterization

The low-temperature undoped GaN buffer layer was grown to a thickness of ~9 nm at 500 °C under an N2 and NH3 atmosphere on ( 01)-oriented monoclinic conductive β-Ga2O3 substrates using a low-pressure, vertical MOCVD reactor. The (

01)-oriented monoclinic conductive β-Ga2O3 substrates using a low-pressure, vertical MOCVD reactor. The ( 01) β-Ga2O3 substrate was doped with Sn to increase its conductivity, whereby Hall measurements revealed an electron concentration in the order of 1018 cm−3. A low-temperature grown GaN buffer layer is known to decrease hillocks in the GaN epilayer surface23,24,25 on the Ga2O3 substrate and decrease the TDD compared to that on AlN buffer layer20. After changing the carrier gas from N2 to H2, the temperature of the substrate was increased to 1020 °C to grow the Si-doped GaN (n-GaN) epilayer (with a carrier density of 4 × 1018 cm−3 and a nominal thickness of ~1.75 μm). The temperature was further increased to 1100 °C during the deposition of the remainder of the Si-doped GaN layer (of ~1.75 μm thickness). This two-step growth process decreases the formation of epicracks by reducing dislocations between the GaN layers grown in the first and the second steps26,27. Current-voltage measurements confirmed that the interface between the Ga2O3 substrate and the GaN epilayer is conductive. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images confirmed that the total thickness of the GaN epilayer was 3.7 μm. InxGa1−xN layers (5 ≤ x ≤ 23) with a nominal thickness of 40 nm were grown on n-GaN/Ga2O3 with a GaN buffer layer by MOCVD. During the InxGa1−xN layer growth, precursors of trimethylgallium (TMGa), trimethylindium (TMIn) and NH3 were used as source gasses and N2 as the carrier gas at a pressure 400 mbar. The growth temperature was varied for different x values: 0.01 (875 °C), 0.05 (820 °C), 0.1 (795 °C), 0.15 (775 °C) and 0.23 (720 °C). For the purpose of comparison, we grew InxGa1−xN films on Al2O3 using similar optimization growth process.

01) β-Ga2O3 substrate was doped with Sn to increase its conductivity, whereby Hall measurements revealed an electron concentration in the order of 1018 cm−3. A low-temperature grown GaN buffer layer is known to decrease hillocks in the GaN epilayer surface23,24,25 on the Ga2O3 substrate and decrease the TDD compared to that on AlN buffer layer20. After changing the carrier gas from N2 to H2, the temperature of the substrate was increased to 1020 °C to grow the Si-doped GaN (n-GaN) epilayer (with a carrier density of 4 × 1018 cm−3 and a nominal thickness of ~1.75 μm). The temperature was further increased to 1100 °C during the deposition of the remainder of the Si-doped GaN layer (of ~1.75 μm thickness). This two-step growth process decreases the formation of epicracks by reducing dislocations between the GaN layers grown in the first and the second steps26,27. Current-voltage measurements confirmed that the interface between the Ga2O3 substrate and the GaN epilayer is conductive. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images confirmed that the total thickness of the GaN epilayer was 3.7 μm. InxGa1−xN layers (5 ≤ x ≤ 23) with a nominal thickness of 40 nm were grown on n-GaN/Ga2O3 with a GaN buffer layer by MOCVD. During the InxGa1−xN layer growth, precursors of trimethylgallium (TMGa), trimethylindium (TMIn) and NH3 were used as source gasses and N2 as the carrier gas at a pressure 400 mbar. The growth temperature was varied for different x values: 0.01 (875 °C), 0.05 (820 °C), 0.1 (795 °C), 0.15 (775 °C) and 0.23 (720 °C). For the purpose of comparison, we grew InxGa1−xN films on Al2O3 using similar optimization growth process.

Cross-sectional and plan-view TEM specimens were prepared using a lamellar lift-out procedure on an FEI Helios focused ion beam scanning electron microscope and cross-sectional imaging was performed on a JEOL 4000 EX TEM operating at 400 kV. The plan-view TEM images were obtained using FEI Tecnai TWIN TEM operated at 120 kV. Atomic resolution High Angle Annular Dark Field-Scanning Transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) study was carried out with a Titan Cs-Probe Corrected (FEI Co.) microscope operated at 300 kV. In order to get the strain maps from the HAADF images, we used The Geometric Phase Analysis (GPA) plug-in package (HREM Research Inc.), which was implemented in the Digital Micrograph software (Gatan). The surface morphology and roughness of the InGaN epilayers were examined by atomic force microscopy (AFM) using the Agilent 5400 scanning probe microscope. The X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) was performed on a Bruker D8 diffractometer system using a Cu Kα1 radiation. The emission characteristics of this GaN epilayer were compared to a similar GaN epilayer grown by the same growth process but with an AlN buffer layer. Photoluminescence (PL) was measured to investigate the optical properties of the n-GaN film using a 325-nm He-Cd laser at different temperatures. The spectra were collected by an Andor monochromator attached to a charge-coupled device camera. The samples were mounted in a closed-cycle helium cryostat for low-temperature PL (6 K). Time-resolved PL (TRPL) experiments were carried out with a Hamamatsu Synchroscan streak camera. The samples were excited by the third harmonic UV (λ = 266 nm) pulses of a mode-locked Ti:sapphire femtosecond pulsed laser (frequency was doubled using a barium borate crystal) with a pulse width of ~150 fs and a power density of 70 W/cm2 (with 76 MHz repetition rate). A Coherent Verdi-V18 diode-pumped solid-state continuous wave laser was used to pump the Ti:sapphire laser. Emission of the sample was detected by a monochromator attached to a UV-sensitive Hamamatsu C6860 streak camera with a temporal resolution of 2 ps. The samples were mounted in a variable temperature open-helium cryostat for measurements between 2 and 300 K.

Results and Discussion

Structural characterization of GaN 2″ wafer

It is important to obtain high quality and uniform wafers for large-size fabrication technology for use in vertical emitting devices. Raman spectroscopy and XRD measurements were used to examine the material quality and uniformity across the whole 2″ wafer. The strain in GaN/( 01) β-Ga2O3 epilayer was estimated by Raman measurements. Figure 1(a) (top panel) indicates the Raman mapping E2(high) peak position across the 2′′ GaN/β-Ga2O3 wafer. The E2(high) mode was confirmed to be sensitive to biaxial strain in GaN epilayers28. The Raman maps reveal a homogenous uniform stress distribution over the entire wafer with a negligible left shift of ~0.7 cm−1 observed between the center (567.3 cm−1) and the edge (568.0 cm−1) of the wafer, indicating that the stress is fully released to the edge. The E2(high) peak exhibits an average value of ~567.93 cm−1 with a very small left shift (−0.07 cm−1) compared to that of bulk relaxed GaN (568 cm−1)28. This strain value indicates that the uniform GaN/Ga2O3 wafer is nearly strain-free, whereby the presence of a very slight tensile strain suggests low TDD (It is noteworthy that the low lattice mismatch between (

01) β-Ga2O3 epilayer was estimated by Raman measurements. Figure 1(a) (top panel) indicates the Raman mapping E2(high) peak position across the 2′′ GaN/β-Ga2O3 wafer. The E2(high) mode was confirmed to be sensitive to biaxial strain in GaN epilayers28. The Raman maps reveal a homogenous uniform stress distribution over the entire wafer with a negligible left shift of ~0.7 cm−1 observed between the center (567.3 cm−1) and the edge (568.0 cm−1) of the wafer, indicating that the stress is fully released to the edge. The E2(high) peak exhibits an average value of ~567.93 cm−1 with a very small left shift (−0.07 cm−1) compared to that of bulk relaxed GaN (568 cm−1)28. This strain value indicates that the uniform GaN/Ga2O3 wafer is nearly strain-free, whereby the presence of a very slight tensile strain suggests low TDD (It is noteworthy that the low lattice mismatch between ( 01) β-Ga2O3 and the GaN film (~4.7%) can effectively reduce TDD). On the other hand, a high-quality GaN/Al2O3 2″ wafer (grown with the same structure) shows a considerable left shift of ~1.4 cm−1 (Fig. 1(a) bottom panel). Furthermore, GaN grown on AlN buffer layer showed a compressive strain in the film with the E2(high) peak shifted to the right by 1.04 cm−1 compared to the bulk GaN20. The wafer uniformity of high-quality GaN grown on (

01) β-Ga2O3 and the GaN film (~4.7%) can effectively reduce TDD). On the other hand, a high-quality GaN/Al2O3 2″ wafer (grown with the same structure) shows a considerable left shift of ~1.4 cm−1 (Fig. 1(a) bottom panel). Furthermore, GaN grown on AlN buffer layer showed a compressive strain in the film with the E2(high) peak shifted to the right by 1.04 cm−1 compared to the bulk GaN20. The wafer uniformity of high-quality GaN grown on ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 is enhanced significantly using GaN buffer layer by formation of nucleation centers, which is particularly beneficial for good quality two-dimensional lateral growth GaN layer29.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 is enhanced significantly using GaN buffer layer by formation of nucleation centers, which is particularly beneficial for good quality two-dimensional lateral growth GaN layer29.

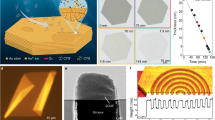

(a) Raman mapping of the E2(high) peak position from the center (red) to the edge (green) of the 2″ n-GaN/( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 wafer (top panel) and n-GaN/sapphire wafer (bottom panel). (b) The XRD RC around GaN (0002) reflection peak on n-GaN/(

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 wafer (top panel) and n-GaN/sapphire wafer (bottom panel). (b) The XRD RC around GaN (0002) reflection peak on n-GaN/( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 wafers with GaN buffer (FWHM = 330 arcsec) and AlN buffer (FWHM = 430 arcsec). 5 × 5-μm2 AFM image of the same wafers with (c) GaN as the buffer layer and (d) AlN buffer layer.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 wafers with GaN buffer (FWHM = 330 arcsec) and AlN buffer (FWHM = 430 arcsec). 5 × 5-μm2 AFM image of the same wafers with (c) GaN as the buffer layer and (d) AlN buffer layer.

To study the reduction in TD, AFM and XRD measurements were conducted across the wafer. The XRD RC analysis of the GaN (0002) reflection peak was performed on the GaN/( 01) β-Ga2O3 wafer. The FWHM value showed a sharper peak of ~330 arcsec (Fig. 1(b)), disclosing a better quality GaN epilayer grown on GaN buffer layer compared to that grown on AlN buffer layer (~430 arcsec), as shown in Fig. 1(b). To the best of our knowledge, this is the best RC FWHM value for GaN obtained for materials grown on a Ga2O3 substrate. This FWHM of the RC confirms that (

01) β-Ga2O3 wafer. The FWHM value showed a sharper peak of ~330 arcsec (Fig. 1(b)), disclosing a better quality GaN epilayer grown on GaN buffer layer compared to that grown on AlN buffer layer (~430 arcsec), as shown in Fig. 1(b). To the best of our knowledge, this is the best RC FWHM value for GaN obtained for materials grown on a Ga2O3 substrate. This FWHM of the RC confirms that ( 01) orientation of β-Ga2O3 substrates improves the crystal quality significantly compared to the (100) orientation (1200 arcsec)21. The surface morphology of GaN epilayers was analyzed by examining the AFM images across the whole wafer. Figure 1(c) illustrates that the GaN grown on (

01) orientation of β-Ga2O3 substrates improves the crystal quality significantly compared to the (100) orientation (1200 arcsec)21. The surface morphology of GaN epilayers was analyzed by examining the AFM images across the whole wafer. Figure 1(c) illustrates that the GaN grown on ( 01) β-Ga2O3 with GaN buffer layer confirms a decrease in TDD (>50%) compared to that with AlN buffer layer (Fig. 1(d)) using the same substrate. The average TDD count (obtained by averaging over >20 AFM 5 × 5 μm2 images at different positions on the 2″ wafer) on GaN buffer layer is found to be 1.8 (±0.2) × 108 cm−2 and that on AlN buffer is 4.5 (±0.2) × 108 cm−2. This low TDD confirms the Raman results, indicating that such substrate can be used for large-scale technology based on GaN vertical light emitting devices.

01) β-Ga2O3 with GaN buffer layer confirms a decrease in TDD (>50%) compared to that with AlN buffer layer (Fig. 1(d)) using the same substrate. The average TDD count (obtained by averaging over >20 AFM 5 × 5 μm2 images at different positions on the 2″ wafer) on GaN buffer layer is found to be 1.8 (±0.2) × 108 cm−2 and that on AlN buffer is 4.5 (±0.2) × 108 cm−2. This low TDD confirms the Raman results, indicating that such substrate can be used for large-scale technology based on GaN vertical light emitting devices.

TEM analysis and low TDD

TEM and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) must be carried out to investigate the actual TDD and analyze the dislocation mechanism. The interface between GaN/β-Ga2O3 was studied by cross-sectional TEM, as shown in Fig. 2. The samples were examined by diffraction contrast, viewing close to the [1 00] zone axis by tilting the sample to excite the g = (0002) and (1

00] zone axis by tilting the sample to excite the g = (0002) and (1 20) Bragg reflections. The electron diffraction pattern taken from the GaN epilayer (the top inset in Fig. 2(a)) shows a single crystal wurtzite (0001) structure with no zinc-blende regions or misoriented grains. Diffraction patterns pertaining to the labeled regions in Fig. 2 are taken near the interface (center inset), revealing a strong epitaxial relationship between the substrate and the GaN epilayer. The bottom inset of Fig. 2 shows an image taken along the GaN [1

20) Bragg reflections. The electron diffraction pattern taken from the GaN epilayer (the top inset in Fig. 2(a)) shows a single crystal wurtzite (0001) structure with no zinc-blende regions or misoriented grains. Diffraction patterns pertaining to the labeled regions in Fig. 2 are taken near the interface (center inset), revealing a strong epitaxial relationship between the substrate and the GaN epilayer. The bottom inset of Fig. 2 shows an image taken along the GaN [1 00] zone axis, parallel to the β-Ga2O3 [110] direction.

00] zone axis, parallel to the β-Ga2O3 [110] direction.

Plan-view TEM analysis was performed to confirm the TDD on the epilayer by bright-field imaging in the vicinity of the [0001] zone axis. Figure 3(a) shows a plan-view TEM image taken under two-beam diffraction conditions, whereby g = (11 0) to allow for accurate determination of the TD from an average of 40 images. The TDD obtained at the centers of GaN grains (of ~1–~2-μm diameter) is considerably lower (~4.8 × 107 cm−2) for that grown on Ga2O3 than that grown on a flat Al2O3 using conventional MOCVD30. As can be seen in Fig. 3(a), TDs appear to migrate to the grain boundaries and are depicted in the image as chains of dark spots delineating the grain boundary. The total average TDD is found to be low (~1.9 (±0.2) × 108 cm−2). This TDD value is in good agreement with the results obtained by Raman and AFM analysis.

0) to allow for accurate determination of the TD from an average of 40 images. The TDD obtained at the centers of GaN grains (of ~1–~2-μm diameter) is considerably lower (~4.8 × 107 cm−2) for that grown on Ga2O3 than that grown on a flat Al2O3 using conventional MOCVD30. As can be seen in Fig. 3(a), TDs appear to migrate to the grain boundaries and are depicted in the image as chains of dark spots delineating the grain boundary. The total average TDD is found to be low (~1.9 (±0.2) × 108 cm−2). This TDD value is in good agreement with the results obtained by Raman and AFM analysis.

(a) Bright-field plan-view TEM micrograph of the n-GaN epilayer showing surface dislocation densities. Cross-sectional TEM image showing a detailed view of the dislocations with (b) g = (1 20) and (c) g = (0002) imaging conditions. (d) A magnified part from cross-sectional view with g = (0002) (panel c), indicating the closed dislocation loops pointed by yellow arrows. (e,f) HRTEM of some of the eliminated dislocation loops near the interface.

20) and (c) g = (0002) imaging conditions. (d) A magnified part from cross-sectional view with g = (0002) (panel c), indicating the closed dislocation loops pointed by yellow arrows. (e,f) HRTEM of some of the eliminated dislocation loops near the interface.

HRTEM analysis and TD annihilation mechanism

To investigate the TDD reduction mechanism, we carried out TEM and HRTEM analyses. The c- and a-components of the Burgers vectors of the TDs are visible, as shown in the cross-sectional images in Fig. 3(b,c), respectively. With diffraction condition g = (0002), only screw and mixed dislocations are visible, whereas edge and mixed components are visible in the g = (1 20) condition31. The (a):(c+a) dislocation ratio is observed to be approximately 1:2, thus differing from the 1:1 ratio typical for dislocation types in standard low TDD GaN grown on (0001) Al2O332. The TEM cross-sectional images (Fig. 3(b,c)) for g = (0002) and g = (1

20) condition31. The (a):(c+a) dislocation ratio is observed to be approximately 1:2, thus differing from the 1:1 ratio typical for dislocation types in standard low TDD GaN grown on (0001) Al2O332. The TEM cross-sectional images (Fig. 3(b,c)) for g = (0002) and g = (1 20) show that the GaN/Ga2O3 interface is abrupt and characterized by a high initial TDD followed by a gradual reduction in the GaN layer (at the distance <200 nm from the substrate) in density as the film continues to grow. Figure 3(d) shows closed dislocation loops (pointed by yellow arrows, taken with g = (0002)). Figure 3(e,f) show a HRTEM cross-sectional view with g = (0002) reflections of TD loops. Figure 3(d–f) demonstrate that the TDs bend into the basal plane and react with dislocations of the opposite phase and are eliminated by forming closed loops in the low-temperature GaN buffer layer and in the lower regions of the GaN epilayer. Therefore, the dislocation does not propagate to the upper part of the GaN epilayer.

20) show that the GaN/Ga2O3 interface is abrupt and characterized by a high initial TDD followed by a gradual reduction in the GaN layer (at the distance <200 nm from the substrate) in density as the film continues to grow. Figure 3(d) shows closed dislocation loops (pointed by yellow arrows, taken with g = (0002)). Figure 3(e,f) show a HRTEM cross-sectional view with g = (0002) reflections of TD loops. Figure 3(d–f) demonstrate that the TDs bend into the basal plane and react with dislocations of the opposite phase and are eliminated by forming closed loops in the low-temperature GaN buffer layer and in the lower regions of the GaN epilayer. Therefore, the dislocation does not propagate to the upper part of the GaN epilayer.

HRTEM and FFT analyses were carried out to investigate the origin of the TD annihilation mechanism. Figure 4(a) shows the HRTEM image of the overlying GaN epilayer, low-temperature grown undoped GaN buffer layer (9 ± 1 nm) and the interface between the buffer layer and the monoclinic β-Ga2O3 substrate. The surface of the flat β-Ga2O3 substrate is characterized by slightly irregular surface “nano hump-features” that reach <4 nm height at the interface. As a result of this irregular feature, the dislocation was grown with an angle with respect to the [0001] direction33, as indicated by the dotted yellow arrow in Fig. 4(a). These dislocation types usually bend and propagate horizontally33. FFT images taken from the overlaying n-GaN epilayer, the buffer layer and the interface are indicated in Fig. 4(b–d), respectively. FFT image (Fig. 4(d) of the interface reveals a complete distortion. This distortion extends to the buffer layer, as shown in the FFT image (Fig. 4(c)) of the low-temperature GaN buffer layer, followed by highly crystalline roughly relaxed n-GaN epilayer, depicted in the FFT image (Fig. 4b). The distortion of the buffer layer may absorb the effect of misfit dislocations caused by lattice mismatch, leading to TD bending in TD in the buffer layer34. These curved dislocations possess Burgers vectors of the same magnitude and opposite direction, which form pairs (Fig. 3(e,f)) and are eliminated near the interface. As a result, the TD propagation to the upper parts of the epilayer ceases. Figure 4(e) shows an HRTEM strain map along the vertical direction, produced by applying the Geometrical Phase Analysis (GPA) program on a dislocation loop with in the buffer layer, confirming the TD elimination near the interface. Furthermore, we observed TD defects grow vertically along the c-axis. Some of these defects stop propagating beyond the first 300 nm above the substrate, as shown in the HRTEM image (Fig. S1, supporting information) due to strain relaxation in the n-GaN epilayer above the distorted buffer layer34. This mechanism of low TDD is posited to be the reason behind the sharp (0002) RC peak of GaN grown on ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 with GaN buffer layer.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 with GaN buffer layer.

(a) HRTEM images of the interface between the overlying GaN layer, low-temperature grown GaN buffer layer and the ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate. An angled Dislocation originating from the interface is shown with a yellow dotted arrow. FFT images are taken from the (b) overlaying n-GaN epilayer, (c) the GaN buffer layer and the (d) interface are shown at different positions (red rectangles). (e) Strain map by GPA method on the area shown in (a) in y-direction as shown in the figure.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 substrate. An angled Dislocation originating from the interface is shown with a yellow dotted arrow. FFT images are taken from the (b) overlaying n-GaN epilayer, (c) the GaN buffer layer and the (d) interface are shown at different positions (red rectangles). (e) Strain map by GPA method on the area shown in (a) in y-direction as shown in the figure.

Optical properties of n-GaN epilayer

A time-integrated low-temperature PL spectrum of the Si-doped GaN/( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 epilayer (GaN buffer layer) is shown in Fig. 5(a). The spectrum displays an intense near-band-edge (NBE) emission under an excitation density of 6 W/cm2, centered at 3.47 eV, which has previously been attributed to band-to-band recombination and to bound and free exciton recombination35,36. The inset of Fig. 5(a) shows that a GaN epilayer grown on a GaN buffer layer rather than on an A1N buffer layer has a 12-fold higher PL intensity at RT with negligible yellow-band luminescence, suggesting a higher quality GaN epilayer and low TDD by using Low-temperature GaN buffer layer. The peak at 3.47 eV (Fig. 5(a)) can be attributed to direct transitions between the conduction and the valence band tail states, as well as random distribution of dopants, resulting in random fluctuations of the doping concentration on a microscopic scale37,38. At RT, a slight broadening in the FWHM of the NBE peak (74 meV) is observed, due to the presence of the Si dopant39. This broadening of the FWHM is expected as a result of high carrier concentration (at the low-energy side) introduced by Si impurities compared to undoped GaN and it can be explained by the tailing of the density of states caused by potential fluctuations introduced by the random distribution of Si dopants39. In addition, residual acceptors may contribute to the NBE peak broadening in the same way by introducing potential fluctuations40. Intensity power dependence studies show that decreasing the excitation intensity by three orders of magnitude produces no significant changes in the observed PL spectra, indicating that no band-gap filling or saturation of the defect level occurs and suggesting that these effects do not contribute to the broadening41. Peaks ascribed to donor-acceptor pair recombination accompanied by longitudinal optical (LO) phonon replicas were observed in the 3.28 − 2.98 eV energy range as shown in Fig. 5(a,b). The phonon replicas are observed in an energy difference of about 97 meV. Figure 5(b) shows a typical temperature-dependent PL spectrum of Si-doped GaN between 8 K and RT. As the temperature increases, the NBE peak weakens and becomes slightly red shifted. The LO phonon replicas weaken dramatically after 150 K and almost disappear at RT.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 epilayer (GaN buffer layer) is shown in Fig. 5(a). The spectrum displays an intense near-band-edge (NBE) emission under an excitation density of 6 W/cm2, centered at 3.47 eV, which has previously been attributed to band-to-band recombination and to bound and free exciton recombination35,36. The inset of Fig. 5(a) shows that a GaN epilayer grown on a GaN buffer layer rather than on an A1N buffer layer has a 12-fold higher PL intensity at RT with negligible yellow-band luminescence, suggesting a higher quality GaN epilayer and low TDD by using Low-temperature GaN buffer layer. The peak at 3.47 eV (Fig. 5(a)) can be attributed to direct transitions between the conduction and the valence band tail states, as well as random distribution of dopants, resulting in random fluctuations of the doping concentration on a microscopic scale37,38. At RT, a slight broadening in the FWHM of the NBE peak (74 meV) is observed, due to the presence of the Si dopant39. This broadening of the FWHM is expected as a result of high carrier concentration (at the low-energy side) introduced by Si impurities compared to undoped GaN and it can be explained by the tailing of the density of states caused by potential fluctuations introduced by the random distribution of Si dopants39. In addition, residual acceptors may contribute to the NBE peak broadening in the same way by introducing potential fluctuations40. Intensity power dependence studies show that decreasing the excitation intensity by three orders of magnitude produces no significant changes in the observed PL spectra, indicating that no band-gap filling or saturation of the defect level occurs and suggesting that these effects do not contribute to the broadening41. Peaks ascribed to donor-acceptor pair recombination accompanied by longitudinal optical (LO) phonon replicas were observed in the 3.28 − 2.98 eV energy range as shown in Fig. 5(a,b). The phonon replicas are observed in an energy difference of about 97 meV. Figure 5(b) shows a typical temperature-dependent PL spectrum of Si-doped GaN between 8 K and RT. As the temperature increases, the NBE peak weakens and becomes slightly red shifted. The LO phonon replicas weaken dramatically after 150 K and almost disappear at RT.

(a) PL spectra of n-GaN/( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 epilayer at 8 K grown on a GaN buffer layer. The inset shows the RT PL spectra in comparison with a GaN epilayer grown on an AlN buffer layer. (b) Temperature dependence of the PL spectrum is measured between 8 K and RT. (c) Time-resolved PL spectra of the n-GaN epilayer measured at RT (squares) and at 4 K (circles) with the double exponential decay fit (red and magenta lines) for each temperature. (d) Temperature dependence of radiative recombination lifetimes (squares) and non-radiative recombination lifetimes (circles) taken from the sample.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 epilayer at 8 K grown on a GaN buffer layer. The inset shows the RT PL spectra in comparison with a GaN epilayer grown on an AlN buffer layer. (b) Temperature dependence of the PL spectrum is measured between 8 K and RT. (c) Time-resolved PL spectra of the n-GaN epilayer measured at RT (squares) and at 4 K (circles) with the double exponential decay fit (red and magenta lines) for each temperature. (d) Temperature dependence of radiative recombination lifetimes (squares) and non-radiative recombination lifetimes (circles) taken from the sample.

Figure 5(c) shows the TRPL spectra of Si-doped GaN/( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 epilayer (GaN buffer layer) at 4K and RT. The TRPL decay time of the Si-doped GaN epilayer can be described by a biexponential fitting. The biexponential decay process occurs in a multilevel system, which arises following the capturing of carriers at the deeper non-radiative centers either in the film or at the interface42,43. The biexponential decay can be described as44,

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 epilayer (GaN buffer layer) at 4K and RT. The TRPL decay time of the Si-doped GaN epilayer can be described by a biexponential fitting. The biexponential decay process occurs in a multilevel system, which arises following the capturing of carriers at the deeper non-radiative centers either in the film or at the interface42,43. The biexponential decay can be described as44,

where A1 and A2 are adjustable constants and τ1 and τ2 are the fast and slow decay times, respectively. Decay times for τ1 and τ2 are measured as 51 ps and 189 ps, respectively, at 4 K and as 71 ps and 352 ps, respectively, at RT. The radiative recombination lifetime of the donor-bound exciton in intentionally and unintentionally doped GaN is typically in the range of 30 to 100 ps45 at RT, increasing to 530 ps at 4 K41. A high donor concentration (1018 cm−1) in a high-quality n-GaN epilayer has previously been shown to lead to a fast decay and a broad spectrum43. Hence, even at low-temperature, it will be difficult to clearly distinguish between free and donor-bound excitons. By defining the internal quantum efficiency ηint(T) as the ratio of the time-integrated PL intensity at each temperature relative to that at the lowest temperature (4 K) and by assuming that the non-radiative channels are inactive at the lowest temperature (in line with the approach used in Rashba’s treatment43), we estimated the values of radiative τrad(T) and non-radiative τnr(T) recombination lifetimes using the following equations:

where τPL(T) is the total recombination lifetime. The radiative and non-radiative recombination lifetimes obtained are plotted in Fig. 5(d). The squares and the circles indicate estimated τrad and τnr, respectively. As the temperature increases from 4 K to RT, τrad increases super-linearly from 51ps to 2.8 ns as shown in Fig. 5(d). Such behavior has been reported at different Si-doping concentrations of GaN46. The decay time behavior of highly Si-doped GaN may be explained by the fact that the recombination is governed by bound excitons at low-temperatures (<10 K), whereas in the intermediate temperature range (20 to 100 K), the free exciton decay rate is largely weakened by the high electron background concentration (due to the presence of Si dopant atoms). Since the sample is heavily doped, the effect of the free excitons is weakened and donor-to-band transitions significantly contribute to the recombination events at intermediate and higher temperatures (~100 to 300 K). However, for undoped- and moderately-doped GaN epilayers, the radiative decay time is considerably enhanced by the free exciton transition43. When temperature increases, the radiative lifetime decreases from 300 to 72 ps and non-radiative lifetime decreases, reflecting the thermal activation of non-radiative recombination processes (Fig. 5(d))43.

The quality of InGaN grown on the n-GaN epilayer

The growth of InxGa1−xN epilayers by MOCVD is influenced by the surface morphology of the underlying n-GaN layer, growth mode, indium incorporation and carrier gas composition47. It is, therefore, necessary to demonstrate that the Ga2O3 substrate can produce high structural and optical quality InxGa1−xN materials grown on this n-GaN/( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 (using GaN buffer layer) that can be used in the development of single and multiple quantum well vertical devices. We investigated the morphology of InxGa1−xN samples through AFM (Fig. 6(a–c) whereby the surface roughness can be represented by the root-mean-square (RMS) average. Figure 6(a–c) show AFM images of In0.1Ga0.9N, In0.15Ga0.85N and In0.23Ga0.77N thin films, respectively, deposited on n-GaN/β-Ga2O3. We observed low RMS roughness values of 0.91, 0.98 and 1.5 nm, for In0.1Ga0.9N, In0.15Ga0.85N and In0.23Ga0.77N, respectively, indicating good quality smooth InGaN films on (

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 (using GaN buffer layer) that can be used in the development of single and multiple quantum well vertical devices. We investigated the morphology of InxGa1−xN samples through AFM (Fig. 6(a–c) whereby the surface roughness can be represented by the root-mean-square (RMS) average. Figure 6(a–c) show AFM images of In0.1Ga0.9N, In0.15Ga0.85N and In0.23Ga0.77N thin films, respectively, deposited on n-GaN/β-Ga2O3. We observed low RMS roughness values of 0.91, 0.98 and 1.5 nm, for In0.1Ga0.9N, In0.15Ga0.85N and In0.23Ga0.77N, respectively, indicating good quality smooth InGaN films on ( 01)-β-Ga2O3 substrates using GaN buffer layer, compared to Al2O3 and Si substates48. At least one pit (dislocation) located in the center of each spiral is observed for all InGaN epilayers, as shown in Fig. 6(a–c). Figure 6(d) shows the normalized PL spectra of these InxGa1−xN thin films, which exhibit an intense NBE emission at RT. The PL NBE peaks arising from In0.05Ga0.95N, In0.1Ga0.9N, In0.15Ga0.85N and In0.23Ga0.77N were observed at 383, 415, 428 and 487 nm, respectively. Moreover, the PL FWHM of these InxGa1−xN NBE peaks increases from 60 to 110 nm with increasing In concentration. The observed FWHM broadening is attributed to carrier localization due to the inhomogeneous compositional fluctuation of InN across the film as In concentration increases49. Furthermore, PL emissions of all InxGa1−xN films grown on the (

01)-β-Ga2O3 substrates using GaN buffer layer, compared to Al2O3 and Si substates48. At least one pit (dislocation) located in the center of each spiral is observed for all InGaN epilayers, as shown in Fig. 6(a–c). Figure 6(d) shows the normalized PL spectra of these InxGa1−xN thin films, which exhibit an intense NBE emission at RT. The PL NBE peaks arising from In0.05Ga0.95N, In0.1Ga0.9N, In0.15Ga0.85N and In0.23Ga0.77N were observed at 383, 415, 428 and 487 nm, respectively. Moreover, the PL FWHM of these InxGa1−xN NBE peaks increases from 60 to 110 nm with increasing In concentration. The observed FWHM broadening is attributed to carrier localization due to the inhomogeneous compositional fluctuation of InN across the film as In concentration increases49. Furthermore, PL emissions of all InxGa1−xN films grown on the ( 01) β-Ga2O3 substrate showed high peak intensity compared to those grown on Al2O3 substrates (Fig. 6(e)), indicating that the β-Ga2O3 substrate is a potential candidate for growing good quality InGaN materials. The blueshift of NBE peak (Fig. 6(e)) of the InGaN sample grown on (

01) β-Ga2O3 substrate showed high peak intensity compared to those grown on Al2O3 substrates (Fig. 6(e)), indicating that the β-Ga2O3 substrate is a potential candidate for growing good quality InGaN materials. The blueshift of NBE peak (Fig. 6(e)) of the InGaN sample grown on ( 01) β-Ga2O3 compared to that grown on Al2O3 can be due to a different degree of strain and InN compositional fluctuation.

01) β-Ga2O3 compared to that grown on Al2O3 can be due to a different degree of strain and InN compositional fluctuation.

The 2.5 × 2.5-μm AFM images of the InxGa1−xN epilayers for different. In concentrations (a) x = 0.1, (b) 0.15 and (c) 0.23. (d) The RT PL spectra of InxGa1−xN films; spectra show oscillations due to interference at interfaces. (e) PL spectra comparison between In0.15Ga0.85N grown on Ga2O3 and Al2O3.

Conclusion

We have reported high optical and structural quality InxGa1−xN epilayers (0 ≤ x ≤ 23) grown on ( 01) β-Ga2O3 substrate using low-temperature undoped GaN buffer layer β-Ga2O3 is a potential substrate material for III-nitrides, which incorporates the transparency of sapphire and the conductivity of SiC. Raman mapping and XRD RC show high-quality uniform and nearly strain-free 2″ wafer grown on (

01) β-Ga2O3 substrate using low-temperature undoped GaN buffer layer β-Ga2O3 is a potential substrate material for III-nitrides, which incorporates the transparency of sapphire and the conductivity of SiC. Raman mapping and XRD RC show high-quality uniform and nearly strain-free 2″ wafer grown on ( 01) β-Ga2O3 substrate by using GaN buffer layer, confirming that this substrate can be used for large-scale technology for nitride-based vertical devices. TEM analysis confirms the low TDD of the single-crystalline epilayers. We found that the TD annihilation occurred near the interface between the substrate and the buffer layer, as a result of TDs bending into the basal plane and reacting with dislocations of the opposite phase, before eliminating each other. The TD bending can be ascribed to the combination of the nature of the (

01) β-Ga2O3 substrate by using GaN buffer layer, confirming that this substrate can be used for large-scale technology for nitride-based vertical devices. TEM analysis confirms the low TDD of the single-crystalline epilayers. We found that the TD annihilation occurred near the interface between the substrate and the buffer layer, as a result of TDs bending into the basal plane and reacting with dislocations of the opposite phase, before eliminating each other. The TD bending can be ascribed to the combination of the nature of the ( 01) β-Ga2O3 surface (nano-humps) and the buffer layer distortion, followed by roughly strain-free single crystal Si-doped GaN epilayer, preventing these TD continuing propagating to this epilayer. The PL measurements revealed a high-intensity NBE emission peak with a weak yellow band, whereas TRPL showed a low non-radiative contribution to the NBE emission. This work demonstrates that improved quality and stable III-nitride crystals grown on (

01) β-Ga2O3 surface (nano-humps) and the buffer layer distortion, followed by roughly strain-free single crystal Si-doped GaN epilayer, preventing these TD continuing propagating to this epilayer. The PL measurements revealed a high-intensity NBE emission peak with a weak yellow band, whereas TRPL showed a low non-radiative contribution to the NBE emission. This work demonstrates that improved quality and stable III-nitride crystals grown on ( 01)-β-Ga2O3 substrate can be obtained, relative to those grown on (100)-orientated β-Ga2O3. We showed that conductive β-Ga2O3 promises better current distribution, thermal management and better light extraction compared to sapphire and testifies to its suitability as a substrate for manufacturing large scale high-efficiency vertical devices, which increases the lifetime and simplifies the fabrication process compared to lateral devices. Dislocation density in nitride films grown on (

01)-β-Ga2O3 substrate can be obtained, relative to those grown on (100)-orientated β-Ga2O3. We showed that conductive β-Ga2O3 promises better current distribution, thermal management and better light extraction compared to sapphire and testifies to its suitability as a substrate for manufacturing large scale high-efficiency vertical devices, which increases the lifetime and simplifies the fabrication process compared to lateral devices. Dislocation density in nitride films grown on ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 may be further reduced as crystal growth continues to be optimized either by lateral overgrowth or substrate patterning.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 may be further reduced as crystal growth continues to be optimized either by lateral overgrowth or substrate patterning.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Muhammed, M. M. et al. High-quality III-Nitride films on conductive, transparent ( 01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 using a GaN buffer layer. Sci. Rep. 6, 29747; doi: 10.1038/srep29747 (2016).

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 using a GaN buffer layer. Sci. Rep. 6, 29747; doi: 10.1038/srep29747 (2016).

References

M. Kneissl et al. Advances in group III-nitride-based deep UV light-emitting diode technology. Semiconductor Science and Technology 26, 014036 (2011).

C. J. Neufeld et al. High quantum efficiency InGaN/GaN solar cells with 2.95 eV band gap. Applied Physics Letters 93, 143502 (2008).

U. K. Mishra, L. Shen, T. E. Kazior & Y. F. Wu . GaN-Based RF power devices and amplifiers. Proceedings of the Ieee. 96, 287–305 (2008).

Z. Wan et al. Microstructural analysis of InGaN/GaN epitaxial layers of metal organic chemical vapor deposition on c-plane of convex patterned sapphire substrate. Thin Solid Films 546, 104–107 (2013).

J.-C. Song et al. Characteristics comparison between GaN epilayers grown on patterned and unpatterned sapphire substrate (0 0 0 1). Journal of Crystal Growth 308, 321–324 (2007).

T. Sugahara et al. Direct evidence that dislocations are non-radiative recombination centers in GaN. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. Part 2 - Lett. 37, L398–L400 (1998).

J. S. Speck & S. J. Rosner . The role of threading dislocations in the physical properties of GaN and its alloys. Physica B: Condensed Matter 273–274, 24–32 (1999).

S. E. Bennett . Dislocations and their reduction in GaN. Materials Science and Technology 26, 1017–1028 (2010).

M. Shiojiri, C. C. Chuo, J. T. Hsu, J. R. Yang & H. Saijo . Structure and formation mechanism of V defects in multiple InGaN∕GaN quantum well layers. Journal of Applied Physics 99, 073505 (2006).

T. Wang et al. Fabrication of high performance of AlGaN/GaN-based UV light-emitting diodes. Journal of Crystal Growth 235, 177–182 (2002).

E. Schmitt, T. Straubinger, M. Rasp & A. D. Weber . Defect reduction in sublimation grown SiC bulk crystals. Superlattices and Microstructures 40, 320–327 (2006).

L. Liu & J. H. Edgar . Substrates for gallium nitride epitaxy. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 37, 61–127 (2002).

P. Tao et al. Enhanced output power of near-ultraviolet LEDs with AlGaN/GaN distributed Bragg reflectors on 6H–SiC by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition. Superlattices and Microstructures 85, 482–487 (2015).

H. H. Tippins . Optical Absorption and Photoconductivity in the Band Edge of β–Ga2O3 . Physical Review 140, A316–A319 (1965).

R. Togashi et al. Thermal stability of β-Ga2O3 in mixed flows of H2 and N2 . Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 54, 041102 (2015).

S. Kiyoshi et al. Epitaxial Growth of GaN on (1 0 0) β-Ga2O3 Substrates by Metalorganic Vapor Phase Epitaxy. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 44, L7 (2005).

Z.-L. Xie et al. Demonstration of GaN/InGaN Light Emitting Diodes on (100) β-Ga2O3 Substrates by Metalorganic Chemical Vapour Deposition. Chinese Physics Letters 25, 2185 (2008).

S. Ito et al. Growth of GaN and AlGaN on (100) β-Ga2O3 substrates. Physica status solidi (c) 9, 519–522 (2012).

V. M. Bermudez . The structure of low-index surfaces of β-Ga2O3 . Chemical Physics 323, 193–203 (2006).

M. M. Muhammed et al. High optical and structural quality of GaN epilayers grown on ( 01) β-Ga2O3 . Applied Physics Letters 105, 042112 (2014).

K. Shimamura et al. Epitaxial Growth of GaN on (1 0 0) β-Ga2O3 Substrates by Metalorganic Vapor Phase Epitaxy. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 44, L7 (2005).

E. G. Víllora, S. Arjoca, K. Shimamura, D. Inomata & K. Aoki, et al. β-Ga2O3 and single-crystal phosphors for high-brightness white LEDs and LDs and β-Ga2O3 potential for next generation of power devices. Proceeding SPIE 8987, 89871U (2014).

T. Lang et al. Multistep method for threading dislocation density reduction in MOCVD grown GaN epilayers. physica status solidi (a) 203, R76–R78 (2006).

A. Usui . Gallium Nitride Crystals Grown by Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy with Dislocation Reduction Mechanism. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2, N3045–N3050 (2013).

Y. P. Hsu et al. Lateral epitaxial patterned sapphire InGaN/GaN MQW LEDs. Journal of Crystal Growth 261, 466–470 (2004).

N. Shuji . GaN Growth Using GaN Buffer Layer. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 30, L1705 (1991).

C. F. Lin et al. The dependence of the electrical characteristics of the GaN epitaxial layer on the thermal treatment of the GaN buffer layer. Applied Physics Letters 68, 3758–3760 (1996).

H. Hiroshi . Properties of GaN and related compounds studied by means of Raman scattering. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 14, R967 (2002).

I. Akasaki, H. Amano, Y. Koide, K. Hiramatsu & N. Sawaki . Effects of ain buffer layer on crystallographic structure and on electrical and optical properties of GaN and Ga1−xAlxN (0 < x ≦ 0.4) films grown on sapphire substrate by MOVPE. Journal of Crystal Growth 98, 209–219 (1989).

M. A. Moram et al. On the origin of threading dislocations in GaN films. Journal of Applied Physics 106, 073513 (2009).

Y. Zhang et al. Efficiency improvement of InGaN light emitting diodes with embedded self-assembled SiO2 nanosphere arrays. Journal of Crystal Growth 394, 7–10 (2014).

E. J. Tarsa et al. Homoepitaxial growth of GaN under Ga-stable and N-stable conditions by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. Journal of Applied Physics 82, 5472–5479 (1997).

S. Gradečak, P. Stadelmann, V. Wagner & M. Ilegems . Bending of dislocations in GaN during epitaxial lateral overgrowth. Applied physics letters 85, 4648–4650 (2004).

H.-Y. Shih et al. Ultralow threading dislocation density in GaN epilayer on near-strain-free GaN compliant buffer layer and its applications in hetero-epitaxial LEDs. Scientific Reports 5, 13671 (2015).

W. Shan et al. Temperature dependence of interband transitions in GaN grown by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Applied Physics Letters 66, 985–987 (1995).

B. Monemar Fundamental energy gap of GaN from photoluminescence excitation spectra. Physical Review B 10, 676–681 (1974).

E. Iliopoulos, D. Doppalapudi, H. M. Ng & T. D. Moustakas . Broadening of near-band-gap photoluminescence in n-GaN films. Applied Physics Letters 73, 375–377 (1998).

T. N. Morgan Broadening of Impurity Bands in Heavily Doped Semiconductors. Physical Review 139, A343–A348 (1965).

E. F. Schubert, I. D. Goepfert, W. Grieshaber & J. M. Redwing . Optical properties of Si-doped GaN. Applied Physics Letters 71, 921–923 (1997).

J. Alam et al. Effect of dislocations on luminescence properties of silicon-doped GaN grown by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition method. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B 22, 624–629 (2004).

G. E. Bunea, W. D. Herzog, M. S. Ünlü, B. B. Goldberg & R. J. Molnar . Time-resolved photoluminescence studies of free and donor-bound exciton in GaN grown by hydride vapor phase epitaxy. Applied Physics Letters 75, 838–840 (1999).

O. Brandt et al. Impact of exciton diffusion on the optical properties of thin GaN layers. Physical Review B 58, R13407–R13410 (1998).

O. Brandt, J. Ringling, K. H. Ploog, H.-J. Wünsche & F. Henneberger . Temperature dependence of the radiative lifetime in GaN. Physical Review B 58, R15977–R15980 (1998).

J. S. Im et al. Radiative carrier lifetime, momentum matrix element and hole effective mass in GaN. Applied Physics Letters 70, 631–633 (1997).

R. A. Mair, J. Li, S. K. Duan, J. Y. Lin & H. X. Jiang . Time-resolved photoluminescence studies of an ionized donor-bound exciton in GaN. Applied Physics Letters 74, 513–515 (1999).

K. P. Korona Erratum: Dynamics of excitonic recombination and interactions in homoepitaxial GaN. Physical Review B 66, 169901 (2002).

S. M. Ting et al. Morphological evolution of InGaN/GaN quantum-well heterostructures grown by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Journal of Applied Physics 94, 1461–1467 (2003).

E. Arslan et al. Evolution of the mosaic structure in InGaN layer grown on a thick GaN template and sapphire substrate. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Electronics 24, 4471–4481 (2013).

K. P. O’Donnell et al. Optical linewidths of InGaN light emitting diodes and epilayers. Applied Physics Letters 70, 1843–1845 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank KAUST for its financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed significantly to this work. M.M.M. wrote the main manuscript and she carried out the PL, TRPL, XRD, AFM, TEM analysis and the TEM FIB preparation. M.A.R. was responsible for high-resolution TEM cross-section and the TEM plan view analysis. I.A.A. contributed on TRPL measurements. S.-L.S. and C.J.H. were responsible for the TEM cross-section measurements. The samples were grown by Y.Y., K.I. and A.K. All the authors have together discussed and interpreted the results. I.S.R. is the principle investigator and supervised all aspects of the study.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Muhammed, M., Roldan, M., Yamashita, Y. et al. High-quality III-nitride films on conductive, transparent (2̅01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 using a GaN buffer layer. Sci Rep 6, 29747 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29747

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29747

This article is cited by

-

Analysis of the chemical states and microstructural, electrical, and carrier transport properties of the Ni/HfO2/Ga2O3/n-GaN MOS junction

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2023)

-

UWBG AlN/β-Ga2O3 HEMT on Silicon Carbide Substrate for Low Loss Portable Power Converters and RF Applications

Silicon (2022)

-

Nano-structured phases of gallium oxide (GaOOH, α-Ga2O3, β-Ga2O3, γ-Ga2O3, δ-Ga2O3, and ε-Ga2O3): fabrication, structural, and electronic structure investigations

International Nano Letters (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 using a GaN buffer layer with electron diffraction patterns collected from the GaN epilayer (top), interface (middle) and substrate (bottom).

01)-oriented β-Ga2O3 using a GaN buffer layer with electron diffraction patterns collected from the GaN epilayer (top), interface (middle) and substrate (bottom).