Abstract

Gymnosporangium species (Pucciniaceae, Pucciniales) cause serious diseases and significant economic losses to apple cultivars. Most of the reported species are heteroecious and complete their life cycles on two different plant hosts belonging to two unrelated genera, i.e. Juniperus and Malus. However, the phylogenetic relationships among Gymnosporangium species and the evolutionary history of Gymnosporangium on its aecial and telial hosts were still undetermined. In this study, we recognized species based on rDNA sequence data by using coalescent method of generalized mixed Yule-coalescent (GMYC) and Poisson Tree Processes (PTP) models. The evolutionary relationships of Gymnosporangium species and their hosts were investigated by comparing the cophylogenetic analyses of Gymnosporangium species with Malus species and Juniperus species, respectively. The concordant results of GMYC and PTP analyses recognized 14 species including 12 known species and two undescribed species. In addition, host alternations of 10 Gymnosporangium species were uncovered by linking the derived sequences between their aecial and telial stages. This study revealed the evolutionary process of Gymnosporangium species and clarified that the aecial hosts played more important roles than telial hosts in the speciation of Gymnosporangium species. Host switch, losses, duplication and failure to divergence all contributed to the speciation of Gymnosporangium species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The plant genus Malus (Rosaceae family) comprises 33 to 55 species and species in this genus were mainly cultivated for fruit production1. They have great economic importance worldwide, especially in China, where apple production accounts for more than half of world production (http://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/fruit.pdf). Cedar-apple rust diseases, caused by species from genus Gymnosporangium R. Hedw. ex DC. (1805) (Pucciniaceae, Pucciniales), are one of the most devastative diseases occurring on apple cultivars. The Gymnosporangium species can infect leaves, fruits and stem of Malus species and cause premature defoliation and eventually kill the plants2,3.

The genus Gymnopsorangium was established to accommodate G. fuscum DC. on Juniperus sabina L4. Up to date, around 57 species have been reported worldwide in this genus5, among which, 17 species were reported with their aecial stage on Malus species6. These 17 species were described by various mycologists in Asia, Europe and North America and they had heteroecious and demicyclic life cycles7. To complete the life cycle, these species have their aecial stage on Malus species and telial stage on Juniperus or Chamaecyparis species5,8.

Taxonomic studies on Gymnopsorangium have long been conducted in Europe, North America and Japan9,10,11. Among the five spore stages (i.e., spermogonium, aecium, uredinium, telium and basidium), morphological characters in aecial and telial stages were of significant importance for species recognition5,10,11,12. However, due to lack of a consistent species concept, different taxonomic systems have employed various morphological characters and aecial or telial host range for species delimitation. Kern5 presented a taxonomic monograph of Gymnosporangium and emphasized the importance of morphology in aecial and telial stages, the phylogenetic significance of those emphasized criteria however, have not been evaluated. In recent years, molecular data have been more and more frequently employed to resolve taxonomic issues especially for species with little morphological variation13,14. However, most of the recent molecular taxonomic studies simply recognized well supported clades as distinct species without implementing careful examination of species boundary; thus, use of coalescent approach has been recommended in order to assess the consistency of delineated species from different models15,16,17.

The first report of Gymnosporangium in China was G. corniforme on J. formosana18. Subsequently, described species in Gymnosporangium gradually increased to five19,20. Based on the aecial spore morphology, Zhuang et al.21 collectively treated the causal agents of 12 Malus hosts as G. yamadae, which were previously recognized as G. asiaticum, G. fenzelianum, G. globosum, G. laeve or G. yamadae19,20 based only on the morphological similarities in the aecial stage. In addition, Zhuang et al.21 speculated that J. chinensis was the telial host of G. yamadae, but lack experimental or molecular evidences.

Previously, uredinologists held the opinions that rust fungi have coevolved with their hosts over long time and cospeciation played the most important role in host and rust fungi evolution22,23. However, recent study indicated that host jump, rather than cospeciation, were the main speciation events driving the evolution of rust fungi24. In the genus Gymnosporangium, controversial opinions were hold among researchers toward the evolutionary relationships with host species. Moran25 suggested that Gymnosporangium species are tightly coevolved with their hosts despite the absence of an overall cospeciation pattern. In contrast, based on the phylogenetic relationship of several Gymnosporangium species, Novick26 thought host switching rather than cospeciation was the primary speciation model in the group. Because only very limited Gymnosporangium species were included in their studies, the evolutionary history and speciation mode of Gymnosporangium species on Malus species remains largely unknown.

The objectives of the current study are: 1) to conduct the species delimitation analyses for Gymnosporangium species; 2) to clarify the host alternation of these recognized Gymnosporangium species on Malus; 3) to conduct the cophylogenetic analyses of Gymnosporangium species with their aecial host and telial host respectively; 4) to infer the speciation modes (cospeciation, duplication, host switch, loss and failure to diverge) of Gymnosporangium species.

Results

Species delimitation

In the GMYC analyses, totally 80 haplotypes were found from 114 specimens and identical haplotypes and two outgroup samples were removed for final analyses. The GMYC analyses using the single- and multiple-threshold models revealed different results (Fig. 1). Both single- and multiple-threshold models were preferred over the null model of uniform branching rates. In the single-threshold analysis, confidence intervals for the estimated number of species varied from 10 to 25 and the model fitted the switch and lead to an estimation of 17 putative species. This species delimitation scenario was not well supported by the result of LR test (P-value = 0.3823). In the multiple-threshold analysis, the model fitted the switch in the branching patterns at 20 to 33 and the results lead to 27 putative species. In comparison with single-threshold analysis, the results from multiple-threshold analysis appeared to be more reliable because it was statistically supported by the result of LR test (P-value = 0.008733775**). In addition, due to different species delimitation scenarios based on single- and multiple-models, STEM was used to estimate the likelihood values of alternative species delimitation scenarios. Based on the protocol by Carstens & Deweya (2010), the likelihood scores of 1-species scenarios, 17-species scenarios and 27-species scenarios were analyzed. STEM analyses also supported a 27-species scenario over other species scenarios. In the PTP analyses, the ML-scenarios recognized 27 species, which was congruent with multiple-threshold GMYC models. Thus, based on concordant results from GMYC and PTP models, 27 species scenarios were recognized.

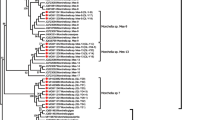

Phylogenetic trees of the combined data of the internal transcribed spacer regions and intervening 5.8S nrRNA gene (ITS) and the large subunit (LSU) rDNA obtained from parsimony analysis.

Bayesian posterior probabilities (Bpp) were given immediately followed by the bootstrap values of ML on the nodes in the topology. Asterisk (*) represented bootstrap values less than 50% or Bpp less than 0.75 in the topology. The first column depicts species recognized by the single-threshold GMYC model and second column depicts putative species recognized by multiple-threshold GMYC model. The third column depicts putative species recognized by PTP model. The name of each putative species was designated based mainly on Kern (1973).

Sequences obtained from this study scattered in 14 putative species. Morphological characters from aecia, peridium, aeciospores, telia and teliospores were observed and recognized among species (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). The proper name of each putative species was determined based on these morphological characters5,9,10,11,12,27,28,29. Our results are in good agreement with the taxonomic system of Kern5. Two unnamed species were recognized by our molecular analyses.

Host alternation

Based on the telial and aecial host information of specimens within each putative species, we clarified the host alternations of 10 species, which were previously unknown. The aecial and telial host ranges of each putative species were summarized in Supplementary Table 2. The telial hosts were mainly recognized in J. chinensis, J. communis, J. horizontalis, J. scopulorum and J. virginiana and they did not show apparent host specificity because six morphologically distinguishable Gymnosporangium species shared J. virginiana as one of the telial hosts. In addition, J. chinensis was also the telial host of seven Gymnoporangium species. Similarly, J. communis was found as host of two species, i.e. G. clavariiforme and G. clavipes. In the aecial stage, M. asiatica, M. micromalus, M. prunifolia and M. spectubilis were shown to be specific to certain Gymnoporangium species, but M. communis, M. malus, M. pumila and M. sylverstris were shown to be the aecial hosts of two or three Gymnosporangium species, respectively.

Divergent time of Gymnosporangium species

The root of the tree was calibrated based on the age of a fossil fungus in the genus Ravenelia. The mean age of the node marking the split of Gymnosporangium species were shown in the Fig. 2. The split of Gymnosporangium species from the genus Ravenelia occurred at the Eocene epoch of the Palaeogene period in the Cenozoic era, approximately 51.7–44.3 Mya with the calibration point of genus Ravenelia (55.8–40.4 Mya, fossil record). It can be recognized that the aecial host ranges gradually decreased in the evolution and divergence of species in Gymnosporangium. The early divergent species, such as G. asiaticum and G. confusum, had relatively wider aecial host range up to seven genera5. However, several recently divergent species, such as G. amelanchieris, G. atlanticum, G. bethelii, G. connersii, G. hemisphaericum, G. juniperi-virginianae, G. nelsonii, G. sabinae and G. yamadae, had their aecial host on only one host genus. On the other hand, no clear tendency was recognized from that of the telial hosts.

Divergence time estimation of Gymnosporangium species using the rDNA dataset.

The chronogram was obtained from the molecular clock analysis using BEAST. The Ravenelia (Raveneliaceae, Pucciniales) fossil was served as a reliable calibration point to estimate the divergent time of Gymnosporangium species. Species with aecial host on Malus species were indicated in red color. The estimated divergence time of telial and aecial hosts were indicated below the geographic time scale. In addition, the potential number of telial and aecial host genera was pointed out following the name of the species based on Kern (1973) and our study.

Cospeciation and cophylogeny

The tanglegrams of phylogenetic associations between Gymnosporangium species and their telial and aecial host species were shown respectively in Figs 3 and 4. Several codivergence events were revealed between Gymnopsorangium species and Juniperus species in Fig. 3, but global congruence between hosts and parasites was not significant. On the contrary, we found high incongruence between host and parasites. Event cost based tests by Jane 4.0 recognized the lowest overall costs recovered using the cost regimes “7”, which penalized cospeciation and assigned cost = 0 to loss and failures to diverge (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4). These reconstructions consisted of six duplications, four host switches, three losses and finally four failures to diverge (Fig. 5).

Cophylogenetic analysis of the Gymnosporangium–Juniperus pathosystem conducted with Jane 4 and using phylogenies including one representative per potential species of parasite and host.

Black branches represent the host phylogeny and blue branches the parasite phylogeny. Violet lines represent original polytomies resolved by Jane to minimize the overall cost of the solution. The cost regime used for the reconstruction was by following event costs: (cospeciation = 2, duplication = 0, host switch = 1, lineage sorting = 1 and failure to diverge = 1). The best-fit reconciliation of the Gymnosporangium and Juniperus trees included 6 duplications, four host switches, three losses and finally four failures to diverge.

Although we found certain codivergence between phylogenies of Gymnosporangium species and that of Malus species in Fig. 4, our results also recognized high discordance between topologies of the parasites and aecial hosts. Based on results from Jane 4.0, we recognized lowest overall costs recovered by cost regimes “6”, which assigned cost = 0 to duplication, host switch and failures to diverge (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 5). These reconstructions included four duplications, seven host switches, fifteen losses and four failures to divergence (Fig. 6).

Cophylogenetic analysis of the Gymnosporangium–Malus pathosystem conducted with Jane 4 and using phylogenies including one representative per potential species of parasite and host.

Black branches represent the host phylogeny and blue branches the parasite phylogeny. The cost regime used for the reconstruction was by following event costs: (cospeciation = 2, duplication = 0, host switch = 0, lineage sorting = 1 and failure to diverge = 0). The best-fit reconciliation of the Gymnosporangium and Malus trees included four duplications, seven host switches, fifteen losses and four failures to divergence.

Discussion

Recent phylogenetic studies confirmed the monophyly of the genus Gymnosporangium24,26,30. While at the species level, there are still considerable disagreements on the delimitation of species. Our results from PTP and GMYC models recognized 14 Gymnosporangium species associated with its aecial host on genus Malus. This delimitation was supported by morphological characters from both aecial and telial stages that should be observed using dissecting microscope, light microscope and scanning electron microscope. Our results uncovered significantly higher species diversity in comparison with previous studies, which recognized one to five species from Malus species based on morphology from single spore stage19,20,21. The importance of polyphasic approaches and morphological characters from both aecial and telial spores were herein demonstrated. This result is in agreement to that of Ono et al.31, who also recognized the importance of morphological characters in both telial and aecial stages for species delimitation in rust fungi Phakopsora ampelopsidis complex.

The understanding of host alternation of rust fungi is important to clarify their species evolution, disease epidemics, plant quarantine and disease control. Life cycle of rust species has been previously mostly investigated based on inoculation experiments and large scale natural surveys5,8. In traditional approaches, basidiospores induced from teliospores were used as inoculums and each potential aecial and telial hosts need to be inoculated to confirm the life cycle of certain rust fungus32,33. The process of inoculation experiment is very time-consuming and laborious and often gave false negative results because many factors, i.e., maturity of the inoculum, conditions of overwintering and inoculum germination and growing conditions of the plants, may affect the inoculation results33. Although many researchers conducted studies on host alternation5,11,34, the life cycles from the majority of rust fungi are still unknown35. Taking rust fungi in Japan as an example, approximately 763 species have been recorded but the life cycles of 46% species remained unknown although systematic studies have been conducted for over a century11. Recently, molecular data have been used to uncover the host alternation of rust fungi, such as Puccinia species36 and Phakopsora species on Grape31. In this study, we confirmed the host alternation between Malus species and Juniperus species of 10 Gymnosporangium species. Among them, the host alternations of G. juniperi-virginianae, G. tremelloides and G. yamadae, were partially consistent with previous inoculation tests recorded by Arthur9, Kern5, Harada33 and Hiratsuka et al.11. Thus, the molecular phylogenetic approach, which connected the sequences obtained from telial and aecial stages respectively, is shown to be a more efficient method to determine the host alternation of rust fungi.

The evolutionary pathways of rust fungi have been categorized into four types: 1) divergence and radiation with hosts; 2) jumps to new unrelated hosts; 3) life cycle expansion; and 4) life cycle reduction23. The evolutionary history of Gymnosporangium, however, appeared to be more complicated and different types of evolutionary patterns occurred at different time periods. Based on morphology and host range in aecial and telial stages, Leppik37 proposed a hypothesis that the evolution of Gymnopsorangium followed the life cycle reduction pattern and the ancestral Juniperus species were actually aecial hosts of some heteroecious rusts. Our estimation of the divergence schedule of hosts and parasite further supported the Leppik’s hypothesis. We estimated the first common ancestor of Gymnosporangium species emerged approximately 51.7–44.3 Mya, but the divergent date of telia host (Juniperus species) appeared much earlier. The recent reports on plant fossils indicated that the divergence time of the genus Juniperus was 71.9–49.7 Mya during the Paleocene or adjacent periods38. On the contrary, the divergence of Malus species (approximately 31.0 Mya in Oligocene) was much later than the emergence of Gymnosporangium ancestor39.

According to Leppik37, the rusts on ancestral Juniperus species became autoecious or microcyclic by losing the connection with their telial hosts (possibly some forest ferns) when the alternate hosts were scarce or absent due to environmental change and the rusts switched to produce urediniospores and teliospores on Juniperus species following “Tranzschel’s Law”23. Such process of evolution has already been supported by the reverse host sequence in comparison with other rust fungi, which commonly have aecial hosts on gymnosperm and telial hosts on angiosperm7,22. After adapting to new environment, Gymnosporangium restored the heteroecism and expanded its aecial host range to many hosts in genera of Rosaceae based on the biogenic radiation rule40 (Supplementary Fig. 2). This evolutionary pathway was supported by our studies because the basal linages in this genus were composed of species (G. asiaticum and G. confusum) with wide aecial hosts range up to seven genera. Our results revealed that life cycle expansion played a major role during the early evolution of Gymnosporangium species.

The diversification of Gymnosporangium species appeared to be gradually replying on their aecial hosts. According to the estimation of the divergence times of hosts and parasites, we found that early divergent Gymnosporangium species have a wider aecial host range at the genus level in comparison with recently divergent species. Except the uncertainty of host ranges in Gymnosporangim sp. 1 and Gymnosporangim sp. 2, our results indicated that the early divergent species group possessed aecial hosts on two to seven genera but the recent divergent species group had their aecial hosts solely on one genus, i.e. Malus5. Host ranges of Gymnosporangium species were shown to gradually decrease in the evolutionary process. All these species have their telial hosts on only one or two genera and no clear tendency could be recognized. We therefore speculated that the aecial hosts played more important roles than telial hosts in the evolution and speciation of Gymnosporangium species.

According to the analysis of cophylogeny at species level, the driving forces of speciation appeared to be more complicated. Previously, host switch was considered to be difficult for Gymnopsorangium species because their life cycles are mainly restricted to Cupressaceae and Rosaceae8. Most Gymnopsorangium species were thought to be tightly coevolved with their host species albeit lack of the overall cospeciation model. Novick26 however, raised a different opinion that host switch was a main speciation pattern. According to Johnson et al.41, the processes in host–parasite coevolutionary histories could be divided into eight different events: cospeciation, failure to speciate, duplication, extinction, missing the boat, incomplete host switching, host switch with extinction, host switch with speciation, host switch with speciation and extinction. Through the molecular clock analyses, McTaggart et al.24 concluded that host jumps, rather than coevolution, were the main speciation events that drove the diversification of rust fungi at family and genus level. They also suspected that cospeciation and host switch might be main force at species level. However, we did not recognize cospeciation event of Gymnosporangium species with its aecial and telial hosts, although codivergences were recognized in the tanglegram of host and parasite phylogenies. Our results revealed that host switch, duplication, losses and failure to divergence all played certain roles in driving the speciation in both Juniperus-parasite system and Malus-parasite system. Among them, the process of host switch with speciation and extinction appeared to play the most important roles in the evolutionary history of Gymnosporangium-Malus system. The noteworthy multiple speciation mechanisms existed in this group might be a reflection of their complicated life cycles, as compared to other phytophathogenic fungi. It is therefore very interesting for future studies to investigate why diversified speciation mechanisms exist in the genus Gymnopsorangium.

Materials and Methods

Fungal specimens

A total of 173 herbarium specimens were loan from the Mycological Herbarium of Institute of Microbiology, CAS, China (HMAS) to cover the largest possible hosts and localities of Gymnosporangium species based on previous taxonomic literatures19,20,21. Specimens with either aecial or telial stage were chosen according to the names on the attached labels and their host information. Among these, 72 specimens were collected from J. chinensis and 101 specimens were collected from Malus species. In addition, 85 specimens, which were labeled as Gymnosporangium species on Malus species and Juniperus species from Europe and North America, were loaned from following herbaria: Plant Pathology Herbarium, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA (CUP); and New York Botanical Garden, New York, USA (NYBG). The detailed information of specimens used in this study is listed in Supplementary Table 6.

DNA extraction, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

For the fungal specimens, single sorus from each specimen was excised and DNAs were extracted from all studied herbarium specimens by using Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. From the crude extracts, 1 to 3 μl DNA templates were used directly for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the internal transcribed spacer regions and intervening 5.8S nrRNA gene (ITS) and the large subunit (LSU) rDNA and nested PCR method was employed to improve the amplification. The detailed information of primers was listed in the Supplementary Table 7 and the annealing temperatures of these target fragments were followed by Beenken et al.42.

The rDNA ITS and LSU were successfully obtained from 72 herbarium specimens and their herbarium number, host species, geographical origins and GenBank accession numbers were shown in Supplementary Table 6. Additional 42 sequence data of Gymnospornagium species, which including both rDNA ITS regions and LSU, were retrieved from GenBank for comparable studies (Supplementary Table 8). Two sequences of Ravenelia species were selected as the outgroups. A dataset was constructed including 114 sequence data. Sequences were manually aligned by using Bioedit v.7.0.943 and multiple alignments were performed in Clustal X v.1.844. Gaps were treated as missing data for all analyses. The Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) in Modeltest v.3.745 was used to estimate the best-fit substitution models. Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses were performed using RAxML v.8.0.X46 and Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses were performed by MrBayes v.3.1.247.

GMYC and PTP analyses

Species were recognized based on the concordant results from GMYC and PTP models. The GMYC model uses the distinct branching patterns between a Yule model (modeling interspecific speciation events) and a coalescent model (modeling expected coalescent times of genes at an intraspecific level) to distinguish between species48. Thus, GMYC model was employed to delimit phylogenetic species. Ultrametric trees required to rim the GMYC algorithm were created using BEAST ver. 1.7.549. Two sets of analyses, single-threshold and multiple-threshold models, were performed in the GMYC and three independent MCMC analyses were run for 100 million generations, sampling trees every 10,000 generations. The posterior tree was summarized using TreeAnnotator after discarding burn-in which was determined by Tracer ver. 1.650. The selected topologies were used to optimize the single- and multiple-threshold GMYC models, using the ‘splits’ package51 available for R 3.0.2 (R Core Team 2013). At last, the program STEM was used to estimate likelihood scores of alternative species delimitation scenarios obtained from single- and multiple-threshold GMYC52 and the putative species scenario was selected based on the value of estimated likelihood scores according to Carstens & Dewey53.

As to the species delimitation by PTP model, it uses the branch lengths to estimate the mean expected number of substitutions per site between two branching events54. The model assumes that each substitution has a small probability of generating a speciation event, the model then implements two independent classes of Poisson processes (one describing speciation and the other describing within species branching events) and searches for transition points between interspecific and intraspecific branching patterns. Potential species clusters are then determined by identifying the clades (or single lineages) that originate after these transition points54. The analyses were conducted on the web server for PTP (available at http://species.h-its.org/ptp/) using the RAxML topology as advocated for this method54.

In this study, the species boundary was determined based on consistent results obtained from GMYC and PTP models. Thereafter, the detailed morphological characters of each specimen were observed under the dissecting microscope (SMZ745, Nikko, Japan), the light microscope (Axio Imager A2, ZEISS, Germany) and the scanning electron microscope (Quanta 200, FEITM, USA). The proper name of each putative species was determined based mainly on the keys developed by Kern5 and Peterson8. Besides, morphological characteristics were compared with the original descriptions and other published descriptions of species involved5,9,10,12,27,29.

Molecular clock analysis

To determine the evolutionary history of Gymnosporangium species, the Ravenelia (Raveneliaceae, Pucciniales) fossil was selected as a reliable calibration point to estimate the divergence time of Gymnosporangium species in the Pucciniales and this genus was separated from other members of the rust fungi at the minimum ages of 55.8–40.4 Mya55. The calculations of molecular clock dated linearized BI trees were performed in BEAST v.1.7.5 with the concatenated sequences of rDNA ITS regions and LSU. BEAST input files were constructed using BEAUti (within BEAST) and the lognormal relaxed molecular clock model and the Yule speciation prior set were used to estimate the divergence times and the corresponding credibility intervals. FigTree v.1.4.0 was used to visualize the resulting tree and to obtain the means and 95% higher posterior densities (HPD).

Cospeciation analysis

To conduct the cospeciation analyses, we tried to extract DNA from aecial and telial host species. Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit was used to extract DNA from plant tissues and rDNA ITS and the large subunit of the ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase gene (rbcL) were selected for amplification. Detailed information of primers and PCR procedures was shown in Supplementary Table 7 and information of specimens and their GenBank accession No. was also shown in Supplementary Table 9. PCR amplification procedure and primers of Robinson et al.1 were used to amplify these two target regions from Malus species. In addition, the same primers and PCR procedure of Adams et al.56, were employed to amplify target regions from Juniperus species. Due to limited sequence variations of rbcL gene among host species, especially Malus species, we only used rDNA ITS regions from host species for further cophylogenetic analyses.

Cospeciation analysis was conducted based on an event-cost based test of cospeciation and Treemap 3.0ß and Jane 4.057 were employed to test for significant congruence between the Gymnosporangium and its aecial and telia host’s topologies, respectively. The tanglegram from the phylogenetic trees and individual associations were built by Treemap. In the event cost based tests implemented by Jane 4.0, a pruned ITS regions and nLSU alignment including only one representative per putative species of hosts and parasites was used for analyses. Cophylogeny mapping in Jane 4.0 used heuristics to reconstruct histories that explain the similarities and differences between associated phylogenies. It prioritized minimizing the overall cost, given a cost regime for evolutionary events including “cospeciation”, “duplication”, “duplication and host switch”, “loss” or “lineage sorting” and “failure to diverge”57,58. In all analyses the number of generations was set to 100 and the population size to 300, with a maximum of 99,999 stored solutions in each run. Statistical analyses were then performed to test whether the cost of the reconstructions obtained was significantly lower than expected by chance. Jane 4.0 was used to generate a pseudorandom sample of minimal costs from a null distribution of problem instances with the same model phylogeny. The null distribution was generated by repeatedly randomizing the host–parasite associations (Random Tip Mapping) and the significant matching of host and parasite phylogenies was evaluated by computing the costs of 1000 replicates to compare the resulting costs to the cost of the original cophylogeny.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhao, P. et al. Inferring phylogeny and speciation of Gymnosporangium species and their coevolution with host plants. Sci. Rep. 6, 29339; doi: 10.1038/srep29339 (2016).

References

Robinson, J. P., Harris, S. A. & Juniper, B. E. Taxonomy of the genus Malus Mill. (Rosaceae) with emphasis on the cultivated apple, Malus domestica Borkh. Plant Syst. Evol. 226, 35–58 (2001).

Li, B. H., Wang, C. X. & Dong, X. L. Research progress in apple diseases and problems in the disease management in China (in Chinese). Plant Prot. 39, 46–54 (2013).

Sinclair, W. A. & Lyon, H. H. Diseases of trees and shrubs. 2nd ed. Ithaca, New York, USA: Cornell University Press. (2005).

Lamarck, J. B. & de Candolle, A. P. Flore française. 2, 1–600 (1805).

Kern, F. D. A revised taxonomic account of Gymnosporangium. University Park, Pennsylvania, USA: Pennsylvania State University Press. (1973).

Farr, D. F. & Rossman, A. Y. Fungal Databases, Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, ARS, USDA. Available at: http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/. (Accessed: 20 October 2015) (2013).

Cummins, G. B. & Hiratsuka, Y. Illustrated genera of rust fungi, 3rdedn. St. Paul, Minnesota, USA: American Phytopathological Society. (2003).

Peterson, R. S. Rust fungi (Uredinales) on Cupressaceae. Mycologia 74, 903–910 (1982).

Arthur, J. C. Manual of the rusts in United States and Canada. West Lafayette, Indiana, USA: Purdue Research Foundation. (1962).

Wilson, M. & Henderson, D. M. The British rust fungi. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (1966).

Hiratsuka, N. et al. The rust flora of Japan. Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan: Tsukuba: Shuppankai,. (1992).

Sydow, P. & Sydow, H. Monographia Uredinearum. III: Melampsoraceae, Zaghouaniaceae, Coleosporiaceae. Berlin, Germany: Borntraeger, Leipzig. (1915).

Virtudazo, E. V., Nakamura, H. & Kakishima, M. Phylogenetic analysis of sugarcane rusts based on sequences of ITS, 5.8 S rDNA and D1/D2 regions of LSU rDNA. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 67, 28–36 (2001).

Tian, C. M., Shang, Y. Z., Zhuang, J. Y., Wang, Q. & Kakishima, M. Morphological and molecular phylogenetic analysis of Melampsora species on poplars in China. Mycoscience 45, 55–66 (2004).

Pons, J. et al. Sequence-based species delimitation for the DNA taxonomy of undescribed insects. Syst. Biol. 55, 595–609 (2006).

Parnmen, S. et al. Using phylogenetic and coalescent methods to understand the species diversity in the Cladia aggregata complex (Ascomycota, Lecanorales). PLoS ONE 7, e52245 (2012).

Singh, G. et al. Coalescent-based species delimitation approach uncovers high cryptic diversity in the cosmopolitan lichen-forming fungal genus Protoparmelia (Lecanorales, Ascomycota). PLoS ONE 10, e0124625 (2015).

Sawada, K. Descriptive catalogue of the Formosan fungi IV. Report of the Department of Agriculture Government Research Institute of Formosa 35, 1–123 (1928).

Tai, F. L. Sylloge Fungorum Sinicorum (in Chinese). Beijing, China: Science Press. (1979).

Zhuang, W. Y. Fungi of northwestern China. : Ithaca, New York, USA, : Mycotaxon Ltd. (2005).

Zhuang, J. Y., Wei, S. X. & Wang, Y. C. Flora fungorum sinicorum. Vol. 41. Uredinales IV. Beijing, China: Science Press. (2012).

Leppik, E. E. Some viewpoints on the phylogeny of rust fungi. II. Gymnosporangium. Mycologia 48, 637–654 (1956).

Hennen, J. F. & Buriticá, P. A. A brief summary of modern rust taxonomic and evolutionary theory. Rep. Tottori Mycol. Inst. 18, 243–256 (1980).

McTaggart, A. R. et al. Host jumps shaped the diversity of extant rust fungi (Pucciniales). New Phytol. 10.1111/nph.13686 (2016).

Moran, N. Benefits of host plant specificity in Uroleucon (Homoptera: Aphididae). Ecology 67, 108–115 (1986).

Novick, R. S. Phylogeny, taxonomy and life cycle evolution in the cedar rust fungi (Gymnosporangium). PhD Thesis, Yale University. New Haven. Connecticut, USA (2008).

Kuprevich, V. F. & Tranzschel, V. G. Rust fungi. 1. Family Melampsoraceae. (ed. Savich, V. P. ) Cryptogamic plants of the USSR. vol 4. Komarova, Russia: Botanicheskogo Instituta, 423–464 (1957).

Lee, S. K. & Kakishima, M. Surface structures of peridial cells of Gymnosporangium and Roestelia (Uredinales). Mycoscience 40, 121–131 (1999).

Yun, H. Y. et al. The rust fungus Gymnosporangium in Korea including two species G. monticola and G. unicorne. Mycologia 1, 790–809 (2009).

Maier, W., Begerow, D., Weiss, M. & Oberwinkler, F. Phylogeny of the rust fungi: an approach using nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Can. J. Bot. 81, 12–23 (2003).

Ono, Y., Chatasiri, S., Pota, S. & Yamaoka, Y. Phakopsora montana, another grapevine leaf rust pathogen in Japan. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 78, 338–347 (2012).

Parmelee, J. A. Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae. Fungi Canadensis 137, 1–2 (1979).

Harada, Y. Pear and apple rusts in Japan, with special reference to their life cycles and host ranges. Rep. Tottori Mycol. Inst. 22, 108–119 (1984).

Klebahn, H. Uredineae (in German). Kryptogamenflora der Mark Brandenburg Va. Berlin, Germany: Leipzig Gebrüder Borntraeger. (1914).

Arthur, J. C. The Uredinales (rusts) of Iowa. Bulletin of Iowa Academy of Science 31, 229–255 (1924).

Anikster, Y. et al. Morphology, life cycle biology and DNA sequence analysis of rust fungi on garlic and chives from California. Phytopathology 94, 569–577 (2004).

Leppik, E. E. Origin and evolution of conifer rusts in the light of continental drift. Mycopathologia et Mycologia Applicata 49, 121–136 (1973).

Mao, K. S., Hao, G., Liu, J. Q., Adam, R. P. & Milne, R. I. Diversification and biogeography of Juniperus (Cupressaceae): variable diversification rates and multiple intercontinental dispersals. New Phytol. 188, 254–272 (2012).

Meyer, H. W. & Manchester, S. R. The Oligocene bridge creek flora of the John Day formation, Oregon.v14. California, USA: University of California Press. (1997).

Leppik, E. E. Some viewpoints on the phylogeny of rust fungi. IV. Biogenic radiation. Mycologia 59, 568–579 (1967).

Johnson, K. P., Adams, R. J., Page, R. D. M. & Clayton, D. H. When do parasites fail to speciate in response to host speciation? Syst. Biol. 52, 37–47 (2003).

Beenken, L., Zoller, S. & Berndt, R. Rust fungi on Annonaceae II: the genus Dasyspora Berk. & M. A. Curtis. Mycologia 104, 659–681 (2012).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 (1999).

Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F. & Higgins, D. G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882 (1997).

Posada, D. & Crandall, K. A. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14, 817–818 (1998).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 (2014).

Huelsenbeck, J. P. & Ronquist, F. Mrbayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755 (2001).

Fujisawa, T. & Barraclough, T. G. Delimiting species using single-locus data and the generalized mixed yule coalescent (GMYC) approach: a revised method and evaluation on simulated datasets. Syst. Biol. 1, 1–18 (2013).

Drummond, A. J. & Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214 (2007).

Rambaut, A., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D. & Drummond, A. J. Tracer v1. 6. Available at: http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer. (Accessed: 1st August 2015) (2014).

Ezard, T., Fujisawa, T. & Barraclough, T. Species limits by threshold statistics. Available at: http://R-Forge.R-project.org/projects/splits/. (Accessed: 21st August 2015) (2009).

Kubatko, L. S., Carstens, B. C. & Knowles, L. L. STEM: species tree estimation using maximum likelihood for gene trees under coalescence. Bioinformatics 1, 1–3 (2009).

Carstens, B. C. & Dewey, T. A. Species delimitation using a combined coalescent and information-theoretic approach: an example from North American myotis bats. Syst. Biol. 59, 400–414 (2010).

Zhang, J. J., Kapli, P., Pavlidis, P. & Stamatakis, A. A. General species delimitation method with applications to phylogenetic placements. Bioinformatics 29, 2869–2876 (2013).

Ramanujan, C. K. & Ramachar, P. Spore dispersal of the rust fungi (Uredinales) from the Miocene lignite of South India. Curr. Sci. 32, 271–272 (1963).

Adams, R. P. & Schwarzbach, A. E. Phylogeny of Juniperus using nrDNA and four cpDNA regions. Phytologia 95, 179–185 (2013).

Conow, C., Fielder, D., Ovadia, Y. & Libeskind-Hadas, R. Jane: a new tool for the cophylogeny reconstruction problem. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 5, 16 (2010).

Charleston, M. A. Jungles: a new solution to the host/parasite phylogeny reconciliation problem. Math. Biosci. 149, 191–223 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by NSFC (31322001) and Fundamental Research on Science and Technology, MOST (2014FY120100). Yingming Li acknowledges NSFC (31110103906) for supporting her visit to Dr. RG Shivas’s lab in Australia for the training on the taxonomy of rust and smut fungi. Besides, we express our gratitude to Dr. Yi-Jian Yao (State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, CAS, Beijing, China), Dr. Scott LaGreca (Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium, Section of Plant Pathology & Plant-Microbe Biology, Cornell University, NY, USA), Dr. Barbara M. Thiers (The New York Botanical Garden, NY, USA), Dr. Cheng-Ming Tian and Dr. Ying-Mei Liang (Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China), for providing dried specimens for this study. We also acknowledge Dr. Jun-Min Liang and Dr. Yong-Zhao Diao for their valuable comments that helped us improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z. and L.C. designed the study. P.Z. F.L. and Y.M.L. performed all the experiments and statistical analyses. P.Z. and L.C. edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for publication.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, P., Liu, F., Li, YM. et al. Inferring phylogeny and speciation of Gymnosporangium species and their coevolution with host plants. Sci Rep 6, 29339 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29339

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29339

This article is cited by

-

Comparative transcriptome analysis of juniper branches infected by Gymnosporangium spp. highlights their different infection strategies associated with cytokinins

BMC Genomics (2023)

-

Species diversity of Basidiomycota

Fungal Diversity (2022)

-

Contribution to rust flora in China I, tremendous diversity from natural reserves and parks

Fungal Diversity (2021)

-

Comparative transcriptomics of Gymnosporangium spp. teliospores reveals a conserved genetic program at this specific stage of the rust fungal life cycle

BMC Genomics (2019)

-

Notes, outline and divergence times of Basidiomycota

Fungal Diversity (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.