Abstract

We demonstrate theoretically all-electric control of the superconducting transition temperature using a device comprised of a conventional superconductor, a ferromagnetic insulator and semiconducting layers with intrinsic spin-orbit coupling. By using analytical calculations and numerical simulations, we show that the transition temperature of such a device can be controlled by electric gating which alters the ratio of Rashba to Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling. The results offer a new pathway to control superconductivity in spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dissipationless flow of electric charge and phase coherence are major driving forces for the research and development of superconducting electronics along with phase coherence. For example, superconducting logic circuits have already been implemented, including computer processors and memory chips that work at frequencies up to several gigahertz1,2,3,4. For spintronics5,6,7,8 the main aim is to create logic and memory devices that exploit both the charge and spin degrees of freedom of electrons and which offer high operating frequencies and low energy consumption9.

In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in the intersection of these fields and new discoveries have enabled the new field of superconducting spintronics10,11. At the interface between a conventional superconductor and a ferromagnet, the singlet electron pairs |↑↓〉 − |↓↑〉 in the superconductor can be transformed into spin-polarized triplet pairs through a two-step process involving spin-mixing and spin-rotation10. Spin-mixing occurs at magnetic interfaces whereas magnetic inhomogeneities12,13 or spin-orbit coupling14,15,16 can rotate triplet Cooper pairs into each other, leading to long-ranged proximity effects in strong ferromagnets17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31.

One important application of superconducting spintronics is to control the temperature Tc at which a material becomes superconducting using spin-valves32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. These systems consist of a superconductor proximity-coupled to two ferromagnetic layers. By changing the relative magnetization direction of two ferromagnets one can toggle superconductivity on and off. A key to achieving this effect lies in whether the magnetic configuration allows generation of spin-polarized Cooper pairs or not. When permitted, the generation of spin-polarized pairs which can penetrate deeper into adjacent ferromagnets opens an extra proximity “leakage channel”. This contributes to the draining of superconductivity from the superconductor and therefore further reduces Tc. Although much research has been dedicated to magnetic control of Tc, it would be beneficial to be able to electrically control Tc, as that would enable integration of superconducting nanostructures into electronic circuits without the requirement of applying magnetic fields, e.g. by changing the quasiparticle distribution45,46.

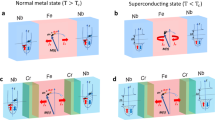

Here we propose a device comprised of a ferromagnetic insulator (FI) and a semiconductor with a two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) in contact with a conventional superconductor (S). Experimentally, it is known that the Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling in a 2DEG can be tuned via a gate voltage47,48,49,50: this voltage can change the Rashba coefficient by a factor of 1.5–2.5 in thin-film structures based on GaAs or InAs47,48,49 and up to a factor of ~6 in nanowires50. These results were obtained for different gate voltage ranges; e.g., ref. 48 varied it from −6 V to +2 V, while ref. 42 used −1.0 V to +1.5 V. It has also been shown that a suitably doped 2DEG can have Rashba and Dresselhaus coefficients of the same order of magnitude, with a ratio of ~1.5 in GaAs/AlGaAs51. It should therefore be possible to engineer a thin-film semiconductor with approximately matching Rashba and Dresselhaus couplings and dynamically modulate the ratio between them by a factor of ~2 via a gate voltage.

Recently, it was demonstrated that the superconductor proximity effect depends strongly on the amount of Rashba and Dresselhaus coupling that is present in the system52. Because of this, we set out to determine if Tc could be controlled purely electrically by tuning the ratio of Rashba to Dresselhaus interactions with an electric field when a 2DEG is in electrical contact to a superconductor via a FI, the latter one serving as a source of triplet pairs. In this work, we confirm this conjecture and predict that all-electric control of Tc is possible in a S/FI/2DEG device. In addition to a gate voltage control, Tc also responds to a change in the FI magnetization orientation, causing our proposed device to function as a combined superconducting transistor and magnetic spin-valve. By superconducting transistor, we mean a device where a gate voltage is used to switch on and off superconductivity in the structure, thus controlling to what extent a supercurrent can flow through the superconductor. This type of functionality is of interest since it corresponds to an electrically controlled transition from finite to zero resistance.

Here we investigate a setup where magnetism and spin-orbit coupling are split into two distinct layers rather than coexisting in the same material52, the former being experimentally more feasible to achieve. Furthermore, whereas previous works have modelled the superconductor/ferromagnet interface using spin-independent tunneling boundary conditions, we here use the recently derived boundary conditions for strongly spin-polarized interfaces53. This means that spin-dependent tunneling, phase-shifts and depairing effects for arbitrarily strong polarization are included in our new model whereas this has not been possible previously in the literature.

Results

Proposed experimental setup

Our proposed experimental setup is sketched in Fig. 1. The electrically controlled superconducting switch is based on an S/FI bilayer grown on an epitaxial GaAs-based (e.g. AlGaAs/GaAs) semiconductor thin-film multilayer. To enable electrical control over the Rasha spin-orbit interaction in the 2DEG, Au gate electrodes are fabricated by electron-beam lithography on a few-nanometer-thick insulating SiO2 layer deposited after the growth and lithographic patterning of the S/FI stack. A four-point probe setup is used to measure changes in the superconducting critical temperature as a function of applied gate voltage Vg. Although the insulating SiO2 layer should minimize possible modulations in the Curie temperature Tc of the FI driven by the applied gate voltage Vg, which can alone have an effect on the superconducting proximity effect, control samples without the FI layer should also be fabricated to exclude this possibility. We also note that the Rasha spin-orbit coupling is independent on the polarity of Vg50. In contrast, Vg usually has an opposite effect on Tc, meaning that a positive Vg normally enhances Tc, while a negative Vg decreases Tc54. Therefore, modulations in Tc due to Vg can also be excluded by investigating variations in the spin-orbit-driven superconducting proximity effect as a function of the Vg polarity.

Analytical results

To explain the mechanism of the electric control of Tc, we first approximate the multilayer structure as an effective monolayer structure where spin-orbit coupling and magnetic exchange fields coexist. This analogy is relevant because the spin-dependent phase-shifts induced by proximity to a FI are known to act as an effective exchange field in thin superconducting structures55. Afterwards, we will confirm the analytical treatment by full numerical simulations performed without these approximations.

To the linear order in the superconducting pair amplitudes, the diffusion equations of the system are52

The symbols  refer to the electron pair amplitudes with spin-singlet, short-range spin-triplet and long-range spin-triplet projections, respectively. We have also defined the the triplet mixing factor

refer to the electron pair amplitudes with spin-singlet, short-range spin-triplet and long-range spin-triplet projections, respectively. We have also defined the the triplet mixing factor

and the effective triplet energies

The ferromagnetism is described by an in-plane exchange splitting h = h(cos θ ex + sin θ ey), which is parametrized in terms of a magnitude h and direction θ. We also assume an in-plane spin-orbit coupling, which is described in polar coordinates by a magnitude  and type χ ≡ atan(α/β), where α and β are the Rashba and Dresselhaus coefficients. The spin-orbit coefficients are defined by the single-particle Hamiltonian

and type χ ≡ atan(α/β), where α and β are the Rashba and Dresselhaus coefficients. The spin-orbit coefficients are defined by the single-particle Hamiltonian  , where m* is the effective mass, p the momentum and σ the spin. Finally, D is the diffusion coefficient of the material and

, where m* is the effective mass, p the momentum and σ the spin. Finally, D is the diffusion coefficient of the material and  is the quasiparticle energy.

is the quasiparticle energy.

The singlet component fs is produced in all conventional superconductors. When these pairs leak into the adjoining ferromagnet, eqs (1, 2, 3) show that a magnetic exchange splitting h induces a nonzero short-ranged triplet component  , as is well-known13. When spin-orbit coupling is present (A ≠ 0), with both Rashba and Dresselhaus contributions (sin 2χ ≠ 0), one also generates the long-range15 triplet component f⊥ so long as the magnetization direction satisfies cos 2θ ≠ 0. It is the latter observation which offers several ways to control the long-ranged triplet generation. Firstly, since the triplet mixing term is proportional to cos 2θ, we may enable this mechanism by letting θ → 0, or disable it by letting θ → ±π/4. Secondly, since the same term is also proportional to sin 2χ, where we defined χ = atan(α/β), the mechanism is enhanced for α ≅ β, but suppressed when α ≪ β or α ≫ β. Since the magnetization direction θ can be changed using an external magnetic field and the Rashba coefficient α can be changed using an external electric field, this means that the triplet mixing can be in principle be controlled using either a magnetic field by itself 56,57,58,59,60, an electric field by itself, or a combination thereof.

, as is well-known13. When spin-orbit coupling is present (A ≠ 0), with both Rashba and Dresselhaus contributions (sin 2χ ≠ 0), one also generates the long-range15 triplet component f⊥ so long as the magnetization direction satisfies cos 2θ ≠ 0. It is the latter observation which offers several ways to control the long-ranged triplet generation. Firstly, since the triplet mixing term is proportional to cos 2θ, we may enable this mechanism by letting θ → 0, or disable it by letting θ → ±π/4. Secondly, since the same term is also proportional to sin 2χ, where we defined χ = atan(α/β), the mechanism is enhanced for α ≅ β, but suppressed when α ≪ β or α ≫ β. Since the magnetization direction θ can be changed using an external magnetic field and the Rashba coefficient α can be changed using an external electric field, this means that the triplet mixing can be in principle be controlled using either a magnetic field by itself 56,57,58,59,60, an electric field by itself, or a combination thereof.

It is important to note that the spin-orbit coupling not only introduces a coupling between the different types of spin-polarized Cooper pairs, but that it also has a depairing effect. This is seen by how A modifies the diagonal terms in the equations above, resulting in an alteration of the effective energies in eqs (5) and (6) associated with the superconducting correlation functions f. Imaginary terms in the effective energy can be interpreted as a destabilization and suppression of the given correlations, so the spin-orbit coupling can suppress either  , f⊥, or both, depending on the parameters χ and θ. It follows from eq. (5) that increasing the magnitude of A and sin 2χ increases this pair-breaking effect, meaning that the same spin-orbit coupling that maximizes the triplet mixing also maximizes the depairing. However, while the mixing term is proportional to cos 2θ, the depairing terms are proportional to sin 2θ. A key observation which enables the purely electric control over Tc is that for a fixed magnetization orientation θ, the depairing energy is controlled by the ratio of Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling χ = atan(α/β). This argument is of importance since we from the numerical simulations find that the dominant effect of the spin-orbit coupling on the critical temperature is not the long-range triplet generation, but rather the short-range triplet suppression. In fact, the most extreme results were obtained for θ = ±π/4, which are precisely the configurations where the linearized diffusion equations disallow triplet mixing.

, f⊥, or both, depending on the parameters χ and θ. It follows from eq. (5) that increasing the magnitude of A and sin 2χ increases this pair-breaking effect, meaning that the same spin-orbit coupling that maximizes the triplet mixing also maximizes the depairing. However, while the mixing term is proportional to cos 2θ, the depairing terms are proportional to sin 2θ. A key observation which enables the purely electric control over Tc is that for a fixed magnetization orientation θ, the depairing energy is controlled by the ratio of Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling χ = atan(α/β). This argument is of importance since we from the numerical simulations find that the dominant effect of the spin-orbit coupling on the critical temperature is not the long-range triplet generation, but rather the short-range triplet suppression. In fact, the most extreme results were obtained for θ = ±π/4, which are precisely the configurations where the linearized diffusion equations disallow triplet mixing.

Numerical results

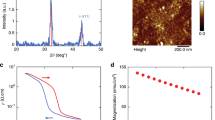

We have calculated Tc numerically and the results are shown in Fig. 2. S is taken as conventional (e.g. Nb), the FI (e.g. GdN, EuO) is treated as a polarized spin-active interface and the semiconducting layer (e.g. GaAs, InAs) is treated as a normal metal with a Rashba–Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling. We used the Ricatti-parametrization61 including the case of spin-orbit coupling52 together with general magnetic boundary conditions53 valid for arbitrary polarization of the interface region. We provide a detailed exposition of the computation of the critical temperature in the Methods section.

Critical temperature results.

(a–c) Critical temperature normalized by the bulk value Tc/Tcs (colors) as a function of the in-plane magnetization angle θ/π (horizontal axis) and spin-orbit ratio α/β (vertical axis). We have used the parameters (a) β = 1, GT/G = 0.2, (b) β = 5, GT/G = 0.2 and (c) β = 5, GT/G = 0.3. (d) Variation [Tc(α/β) − Tc(0.5)]/Tcs in the critical temperature as a function of α/β when θ/π = −0.25. The different curves correspond to the systems used in (a–c). For other magnetization angles |θ/π| ≠ 0.25, the variation of Tc with α/β is non-monotonic since such orientations allow for long-range triplet generation.

For all structures, we assumed a thickness of 0.65ξ for the superconductor and 0.15ξ for the 2DEG, where ξ is the zero-temperature coherence length of a bulk superconductor. Assuming ξ = 30 nm, this would imply a superconductor thickness of ~20 nm and thickness of ~4 nm for the spin-orbit coupled layer. As for the magnitude of the spin-orbit coupling, we normalized both α and β to  . If the effective quasiparticle mass m* is assumed equal to the bare electron mass and we again set ξ = 30 nm, we find that α, β = 1 in dimensionless units corresponds to a coupling α/m*, β/m* = 2.2 × 10−12 eV m. The spin-active interface was taken to have an experimentally realistic spin-polarization of 50%, a tunneling conductance GT/G ∈ {0.2, 0.3} and a spin-mixing conductance Gφ/GT = 1.25, where G is the bulk normal-state conductance of both materials (taken as equal for simplicity). We have run extensive Tc calculations for other parameter values as well (not shown here), where we find qualitatively the same behavior as in Fig. 2, but quantitatively less variation if either the tunneling conductance GT is reduced, the spin-mixing conductance Gφ is reduced, or the spin-polarization is increased. In particular, depending on the quality of the contact between the 2DEG and the FI layer, the tunneling conductance could be very small compared to the normal-state conductance, GT ≪ G.

. If the effective quasiparticle mass m* is assumed equal to the bare electron mass and we again set ξ = 30 nm, we find that α, β = 1 in dimensionless units corresponds to a coupling α/m*, β/m* = 2.2 × 10−12 eV m. The spin-active interface was taken to have an experimentally realistic spin-polarization of 50%, a tunneling conductance GT/G ∈ {0.2, 0.3} and a spin-mixing conductance Gφ/GT = 1.25, where G is the bulk normal-state conductance of both materials (taken as equal for simplicity). We have run extensive Tc calculations for other parameter values as well (not shown here), where we find qualitatively the same behavior as in Fig. 2, but quantitatively less variation if either the tunneling conductance GT is reduced, the spin-mixing conductance Gφ is reduced, or the spin-polarization is increased. In particular, depending on the quality of the contact between the 2DEG and the FI layer, the tunneling conductance could be very small compared to the normal-state conductance, GT ≪ G.

The results in Fig. 2 display the same basic dependence on the magnetic field direction: the critical temperature is maximal when θ →− π/4 and minimal when θ → +π/4. It is interesting to note how spin-valve functionality is obtained in the present structure with just one magnetic layer, tuning Tc from a maximum to minimum upon 90 degrees rotation of the magnetization. The magnitude of this variation depends strongly on the parameters. For strong spin-orbit coupling and moderate interface conductance, we see a variation of nearly 0.6Tcs in Fig. 2, where Tcs is the critical temperature of a bulk superconductor. This corresponds to 5.5 K for niobium; for comparison, the current experimental record for spin-valve effects is around 1 K62. Furthermore, in the region where θ > 0, the critical temperature drops to zero, which means that such a device could in principle function as a spin-valve even at absolute zero. Increasing the interface polarization or weakening the spin-orbit coupling diminishes this effect.

The most interesting observation is nevertheless that we can achieve all-electric control over Tc for a fixed orientation θ of the FI magnetic moment. One particularly striking example is seen in Fig. 2: for a range of magnetization orientations θ, Tc increases from absolute zero at α/β = 1 to a substantial fraction of the bulk critical temperature Tcs as α/β is either increased or decreased. For instance, when θ/π = −0.125, Tc = 0 at α/β = 1 while Tc = 0.42Tcs at α/β = 1.5. For e.g. niobium, this yields a variation of 3.9 K by increasing the Rashba coefficient α by 50%. We highlight this behavior in Fig. 3, where Tc is plotted against the spin-orbit coupling ratio α/β for a fixed magnetization orientation. Moreover, we show in Fig. 3 the large change in Tc that occurs when altering the in-plane magnetization orientation θ for a fixed α/β.

Critical temperature highlights.

Normalized critical temperature Tc/Tcs as function of the spin-orbit coupling ratio α/β (blue line, θ/π = −0.125) and as function of the in-plane magnetization θ (red line, α/β = 1.5). The other parameters are the same as in Fig. 2.

Let us now interpret the numerical findings in terms of the previous analytical treatment. Although the 2DEG by itself has no intrinsic exchange field, rendering the distinction between short-ranged and long-ranged pairs more accurately described by the terminology “opposite and equal spin-pairing states relative the FI orientation”, we will continue to refer to  as short-ranged pairs for brevity and easy comparison with the analytical treatment. When α → β and θ →− π/4, the short-ranged triplet energy

as short-ranged pairs for brevity and easy comparison with the analytical treatment. When α → β and θ →− π/4, the short-ranged triplet energy  , resulting in a strong suppression of these triplet pairs. By closing the triplet proximity channel, this reduces the leakage of Cooper pairs from the superconductor, thus increasing the critical temperature of the structure. On the other hand, when α → β and θ →+ π/4, the energy

, resulting in a strong suppression of these triplet pairs. By closing the triplet proximity channel, this reduces the leakage of Cooper pairs from the superconductor, thus increasing the critical temperature of the structure. On the other hand, when α → β and θ →+ π/4, the energy  , resulting in a minimal suppression of short-ranged triplets. This causes a larger leakage from the superconductor and decreases the critical temperature. This leading-order analysis of the physics is in accordance with the numerical results in Fig. 2, as is reasonable since the weak proximity effect described by the linearized equations is expected to be a good approximation for T ≅ Tc.

, resulting in a minimal suppression of short-ranged triplets. This causes a larger leakage from the superconductor and decreases the critical temperature. This leading-order analysis of the physics is in accordance with the numerical results in Fig. 2, as is reasonable since the weak proximity effect described by the linearized equations is expected to be a good approximation for T ≅ Tc.

Discussion

In the quasiclassical theory used to compute the critical temperature, one assumes that the thickness of the layer exceeds the Fermi wavelength. This criterion is not satisfied in a 2DEG, which means that phenomena such as weak localization/antilocalization cannot be described by quasiclassical theory. However, the coupling mechanism governing the appearance of a superconducting triplet proximity channel in the system is not expected to change because of this and hence our results should remain qualitatively valid even in this scenario. Moreover, we have considered the diffusive limit of transport which is of relevance for the in-plane motion, whereas the 2DEG thickness is much smaller than the mean free path. There is nevertheless scattering at the multiple interfaces of our structure which is expected to enhance the effective diffusive character of quasiparticle motion considered in our model. 2DEGs can also feature a rather strong spin-orbit interaction, in which case corrections to the Usadel equation have been examined63. It could also be of interest to go beyond quasiclassical theory to study Tc and other proximity effects in this kind of system64, although this is beyond the scope of the present work.

Semiconductors such as GaAs and InAs are known to provide both an intrinsic Dresselhaus coupling and an electrically tunable Rashba coupling48,49,50. By combining such 2DEG materials with a superconductor and a ferromagnetic insulator, we have shown both analytically and numerically that Tc responds to changes in both electric and magnetic fields, either individually or combined. It should therefore be possible to create a device that can function as a superconducting transistor, superconducting spin-valve, or both, depending on whether electric or magnetic stimuli are used as the input signal.

Methods

Diffusion equation

In the diffusive and quasiclassical limit, we can describe the structures discussed herein with the Usadel diffusion equation15,16,52

where  is the retarded quasiclassical propagator in Nambu ⊗ Spin space,

is the retarded quasiclassical propagator in Nambu ⊗ Spin space,  is the third Pauli matrix in Nambu space,

is the third Pauli matrix in Nambu space,  is the quasiparticle energy of the electrons and holes,

is the quasiparticle energy of the electrons and holes,  , Δ is the superconducting gap,

, Δ is the superconducting gap,  , h is the ferromagnetic exchange field, σ is the Pauli vector in spin space and D is the diffusion coefficient. The notation

, h is the ferromagnetic exchange field, σ is the Pauli vector in spin space and D is the diffusion coefficient. The notation  is used for the gauge covariant derivative, where

is used for the gauge covariant derivative, where  is a background field that accounts for spin-orbit coupling. In this paper, we assume that we have a thin-film structure oriented along the z-axis so ∇ → ∂z. We assume the exchange field and Rashba–Dresselhaus coupling are both confined to the xy-plane, so they can be parametrized as

is a background field that accounts for spin-orbit coupling. In this paper, we assume that we have a thin-film structure oriented along the z-axis so ∇ → ∂z. We assume the exchange field and Rashba–Dresselhaus coupling are both confined to the xy-plane, so they can be parametrized as

Note that it is the orientation of the spin-orbit field A that defines the x- and y-axes of our coordinate system, since the Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling is determined by the crystal structure. Thus, the magnetic orientation is measured relative to the crystal structure.

Numerically, solving directly for the propagator  is impractical for two reasons. Firstly, the elements of

is impractical for two reasons. Firstly, the elements of  are unbounded and can be arbitrarily large complex numbers. Secondly, the propagator satisfies a normalization condition and particle-hole symmetry which reduces the number of degrees of freedoms, such that solving for each individual matrix element in

are unbounded and can be arbitrarily large complex numbers. Secondly, the propagator satisfies a normalization condition and particle-hole symmetry which reduces the number of degrees of freedoms, such that solving for each individual matrix element in  would be redundant. Because of this, we have used the so-called Riccati parametrization of the propagators in the numerical simulations61:

would be redundant. Because of this, we have used the so-called Riccati parametrization of the propagators in the numerical simulations61:

where the Riccati parameters γ and  are 2 × 2 matrices in spin space which are related by tilde-conjugation

are 2 × 2 matrices in spin space which are related by tilde-conjugation  and the normalization matrices are defined by

and the normalization matrices are defined by  . For an in-plane spin-orbit interaction, eq. (7) parametrizes as

. For an in-plane spin-orbit interaction, eq. (7) parametrizes as

which is the form we use numerically. For more information about the derivation and interpretation of the above, see ref. 52.

Gap equation

Before we can calculate the critical temperature of a material, we require not only a way to calculate the propagator  , but also a way to dynamically update the superconducting gap Δ based on the calculated propagators. This gap equation can be written52

, but also a way to dynamically update the superconducting gap Δ based on the calculated propagators. This gap equation can be written52

where λ is a dimensionless coupling constant, fs the singlet component of the anomalous propagator, Δ0s the zero-temperature gap of a bulk superconductor, Tcs the critical temperature of a bulk superconductor and c the Euler–Mascheroni constant. In terms of the Riccati parametrization, fs = [Nγ]12 − [Nγ]21, where the subscript notation refers to individual matrix elements.

Boundary conditions

Since our purpose is to model a system where the superconductivity, ferromagnetism and spin-orbit coupling originate from different thin-film layers, we need boundary conditions that connect the propagators of these materials at the interfaces. Numerically, we focused on S/FI/N structures, in which case the ferromagnetic insulator itself is modelled as a strongly polarized spin-active interface. We have used the low-transparency limit of the general spin-active boundary conditions derived in ref. 53,

where  is the 4 × 4 matrix current on the left side of the interface, GT is the tunneling conductance of the interface, G1 describes the interfacial depairing, GMR describes the magnetoresistance, Gφ describes the spin-mixing,

is the 4 × 4 matrix current on the left side of the interface, GT is the tunneling conductance of the interface, G1 describes the interfacial depairing, GMR describes the magnetoresistance, Gφ describes the spin-mixing,  , m is a unit vector that describes the interface magnetization and

, m is a unit vector that describes the interface magnetization and  and

and  describes the propagators on the left and right side of the interface, respectively. An equivalent equation for the other side of the interface can be found by letting

describes the propagators on the left and right side of the interface, respectively. An equivalent equation for the other side of the interface can be found by letting  and L ↔ R in the equation above. Assuming that all the interface scattering have the same polarization P, it can be shown that

and L ↔ R in the equation above. Assuming that all the interface scattering have the same polarization P, it can be shown that  and

and  , so we can calculate G1 and GMR directly from the interface polarization.

, so we can calculate G1 and GMR directly from the interface polarization.

The matrix current is related to the propagators at the interface by  where G is the normal-state conductance and L the length of the material. It can then be shown that the Riccati parameters must satisfy the boundary condition

where G is the normal-state conductance and L the length of the material. It can then be shown that the Riccati parameters must satisfy the boundary condition

where I12 and I11 refers to the top-right and top-left 2 × 2 blocks of the 4 × 4 matrix current  . In this equation, the matrix current

. In this equation, the matrix current  should be interpreted as either

should be interpreted as either  or

or  , depending on which side of the interface the boundary conditions should describe.

, depending on which side of the interface the boundary conditions should describe.

Critical temperature

The critical temperature can be defined as the temperature Tc such that the superconducting gap Δ = 0 if and only if T ≥ Tc. However, in practice, we cannot expect to obtain the exact result Δ = 0 in simulations due to inexact numerical methods and random floating-point errors. For numerical simulations, we therefore use a more relaxed criterion |Δ| < δ to define the critical temperature Tc, where we have set δ = 10−5Δ0s and Δ0s is the zero-temperature gap of a bulk superconductor. See the solid black curve in Fig. 4 for a sketch of how Δ(T) typically behaves and how this is related to the critical temperature Tc.

Sketch of the superconducting gap Δ as a function of temperature T for a superconducting hybrid structure.

When performing a binary search for the critical temperature, we check whether Δ > δ at a certain number of temperatures–in other words, whether the black solid line is above the red dashed line. The numbered markers show which points on the curve would be evaluated during the first five bisections of such a binary search and in what order. Note that since the algorithm is actually looking for the intersection between the black solid curve and red dashed curve, we need δ ≪ Δ0s to obtain accurate results.

Conceptually, the simplest way to find this critical temperature is to explicitly calculate the superconducting gap Δ as a function of temperature T and check directly at which temperature we first find |Δ| < δ. However, such a linear search can be very costly when a high accuracy is desired. For instance, to determine the critical temperature to a precision of 0.0001Tcs, where Tcs is the critical temperature of a bulk superconductor, this would require that Δ(T) be calculated for 10,000 different values of T. For each of these temperatures, we need to solve a set of nonlinear diffusion equations for 150 positions and 800 energies and repeat this procedure in one material of the hybrid structure at a time until a selfconsistent solution is found. Thus, the calculation at each of these 10,000 temperatures can in some cases take hours, making this method quite inefficient.

We have instead used a much more efficient binary search algorithm to determine the critical temperature numerically. The main benefit of this algorithm is that after calculating Δ(T) for N particular values of T, we can determine the critical temperature to a precision Tcs/2N+1. So in contrast to the linear search algorithm, an accuracy of around 0.0001Tcs would require calculations at 12 temperatures instead of 10,000. Furthermore, we do not actually need to calculate Δ(T) exactly at these temperatures–it is sufficient to check whether |Δ| < δ or |Δ| > δ to determine whether T > Tc or T < Tc. Thus, at each of these 12 temperatures, we only have to initialize the entire system to a BCS superconducting state with Δ = δ, then solve the Usadel equation and gap equation a fixed number of times in each material and finally check whether |Δ| < δ or |Δ| > δ to determine whether T is an upper or lower bound on Tc. How the binary search algorithm converges is illustrated in Figs 4 and 5.

Sketch of how the binary search algorithm works.

The blue dotted line at T = Tc shows the critical temperature we wish to find, the solid black line shows the critical temperature estimate after N bisections and the red dashed lines shows the bounds for the critical temperature after N bisections. After N bisections, Tc has been determined with an accuracy Tcs/2N+1.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ouassou, J. A. et al. Electric control of superconducting transition through a spin-orbit coupled interface. Sci. Rep. 6, 29312; doi: 10.1038/srep29312 (2016).

References

Dorojevets, M., Bunyk, P. & Zinoviev, D. FLUX chip: design of a 20-GHz 16-bit ultrapipelined RSFQ processor prototype based on 1.75-pm LTS technology. IEEE T. Appl. Supercond. 11, 326 (2001).

Likharev, K. K. & Semenov, V. K. RSFQ logic/memory family: a new Josephson-junction technology for sub-terahertz-clock-frequency digital systems. IEEE T. Appl. Supercond. 1, 3 (1991).

Nagasawa, S., Hashimoto, Y., Numata, H. & Tahara, S. A 380 ps, 9.5 mW Josephson 4-kbit RAM operated at a high bit yield. IEEE T. Appl. Supercond. 5, 2447 (1995).

Tanaka, M. et al. Demonstration of a single-flux-quantum microprocessor using passive transmission lines. IEEE T. Appl. Supercond. 15, 400 (2005).

Johnson, M. & Silsbee, R. H. Interfacial charge-spin coupling: injection and detection of spin magnetization in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1790 (1985).

Ralph, D. C. & Stiles, M. D. Spin transfer torques. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 320, 1190 (2008).

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472 (1988).

Binasch, G., Grunberg, P., Saurenbach, F. & Zinn, W. Enhanced magnetoresistance in layered magnetic structures with antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange. Phys. Rev. B 39, 4828(R) (1989).

Brataas, A., Kent, A. & Ohno, H. Current-induced torques in magnetic materials. Nat. Mater. 11, 372 (2012).

Eschrig, M. Spin-polarized supercurrents for spintronics. Phys. Today 64, 43 (2011).

Linder, J. & Robinson, J. W. A. Superconducting spintronics. Nat. Phys. 11, 307 (2015).

Bergeret, F. S., Volkov, A. F. & Efetov, K. B. Long-range proximity effects in superconductor-ferromagnet structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4096 (2001).

Buzdin, A. I. Proximity effects in superconductor-ferromagnet heterostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 935 (2005).

Annunziata, G., Manske, D. & Linder, J. Proximity effect with noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 86, 174514 (2012).

Bergeret, F. S. & Tokatly, I. V. Singlet-triplet conversion and the long-range proximity effect in superconductor-ferromagnet structures with generic spin dependent fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 117003 (2013).

Bergeret, F. S. & Tokatly, I. V. Spin-orbit coupling as a source of long-range triplet proximity effect in superconductor-ferromagnet hybrid structures. Phys. Rev. B 89, 134517 (2014).

Robinson, J. W. A., Witt, J. D. S. & Blamire, M. G. Controlled injection of spin-triplet supercurrents into a strong ferromagnet. Science 329, 59 (2010).

Khaire, T. S., Khasawneh, M. A., Pratt, W. P. & Birge, N. O. Observation of spin-triplet superconductivity in co-based Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 137002 (2010).

Klose, C. et al. Optimization of spin-triplet supercurrent in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127002 (2012).

Witt, J. D. S., Robinson, J. W. A. & Blamire, M. G. Josephson junctions incorporating a conical magnetic holmium interlayer. Phys. Rev. B 85, 184526 (2012).

Robinson, J. W. A., Chiodi, F., Halász, G. B., Egilmez, M. & Blamire, M. G. Supercurrent enhancement in Bloch domain walls. Sci. Rep. 2, 699 (2012).

Banerjee, N., Robinson, J. W. A. & Blamire, M. G. Reversible control of spin-polarized supercurrents in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 5, 4771 (2014).

Robinson, J. W. A., Banerjee, N. & Blamire, M. G. Triplet pair correlations and nonmonotonic supercurrent decay with Cr thickness in Nb/Cr/Fe/Nb Josephson devices. Phys. Rev. B 89, 104505 (2014).

Di Bernardo, A. et al. Signature of magnetic-dependent gapless odd frequency states at superconductor/ferromagnet interfaces. Nat. Commun. 6, 8053 (2015).

Anwar, M. S., Czeschka, F., Hesselberth, M., Porcu, M. & Aarts, J. Long-range supercurrents through half-metallic ferromagnetic CrO2 . Phys. Rev. B 82, 100501(R) (2010).

Kalcheim, Y., Millo, O., Egilmez, M., Robinson, J. W. A. & Blamire, M. G. Evidence for anisotropic triplet superconductor order parameter in half-metallic ferromagnetic La0.7Ca0.3Mn3O proximity coupled to superconducting Pr1.85Ce0.15CuO4 . Phys. Rev. B 85, 104504 (2012).

Egilmez, M. et al. Supercurrents in half-metallic ferromagnetic La0.7Ca0.3MnO3 . Europhys. Lett. 106, 37003 (2014).

Kalcheim, Y. et al. Magnetic field dependence of the proximity-induced triplet superconductivity at ferromagnet/superconductor interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 89, 180506(R) (2014).

Kalcheim, Y., Millo, O., Di Bernardo, A., Pal, A. & Robinson, J. W. A. Inverse proximity effect at superconductor-ferromagnet interfaces: evidence for induced triplet pairing in the superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 92, 060501(R) (2015).

Di Bernardo, A., Salman, Z., Wang, X. L., Amado, M., Egilmez, M., Flokstra, M. G., Suter, A., Lee, S. L., Zhao, J. H. Prokscha, T., Morenzoni, E. Blamire, M. G., Linder, J. & Robinson, J. W. A. Intrinsic paramagnetic Meissner effect due to s-wave odd-frequency superconductivity. Physical Review X5, 041021 (2015).

Banerjee, N., Smiet, C. B., Smits, R. G. J., Ozaeta, A., Bergeret, F. S., Blamire, M. G. & Robinson, J. W. A. Evidence for spin-selectivity of triplet pairs in superconducting spin-valves. Nature Communications5, 3340 (2014).

Oh, S., Youm, D. & Beasley, M. R. A superconductive magnetoresistive memory element using controlled exchange interaction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 71, 2376 (1997).

Tagirov, L. R. Low-field superconducting spin switch based on a superconductor ferromagnet multilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 02058 (1999).

Buzdin, A. & Vedyayev, A. Spin-orientation–dependent superconductivity in F/S/F structures. Europhys. Lett. 686 (1999).

Bobkov, A. M. & Bobkova, I. V. Enhancing of the critical temperature of an in-plane FFLO state in heterostructures by the orbital effect of the magnetic field. JETP Lett. 99, 333 (2014).

Gu, J. Y. et al. Magnetization-orientation dependence of the superconducting transition temperature in the ferromagnet-superconductor-ferromagnet system: CuNi/Nb/CuNi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 267001 (2002).

Moraru, I. C., Pratt, W. P. & Birge, N. O. Magnetization-dependent Tc shift in ferromagnet/superconductor/ferromagnet trilayers with a strong ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 037004 (2006).

Fominov, Y. V. et al. Superconducting triplet spin valve. JETP Lett. 91, 308 (2010).

Zhu, J., Krivorotov, I. N., Halterman, K. & Valls, O. T. Angular dependence of the superconducting transition temperature in ferromagnet-superconductor-ferromagnet trilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 207002 (2010); Jara, A.A. et al. Angular dependence of superconductivity in superconductor/spin-valve heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B89, 184502 (2014).

Banerjee, N. et al. Evidence for spin selectivity of triplet pairs in superconducting spin valves. Nat. Commun. 5, 3048 (2014); Wang, X. L. et al. Giant triplet proximity effect in superconducting pseudo spin valves with engineered anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B89, 140508(R) (2014).

Chiodi, F. et al. Supra-oscillatory critical temperature dependence of Nb-Ho bilayers. Europhys. Lett. 101, 37002 (2013).

Gu, Y. et al. Magnetic state controllable critical temperature in epitaxial Ho/Nb bilayers. APL Mat. 2, 46103 (2014).

Gu, Y., Halász, G. B., Robinson, J. W. A. & Blamire, M. G. Large superconducting spin valve effect and ultrasmall exchange splitting in epitaxial rare-earth-niobium trilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 067201 (2015).

Wang, X. L., Di Bernardo, A., Banerjee, N., Wells, A., Bergeret, F. S., Blamire, M. G. & Robinson, J. W. A. Giant triplet proximity effect in superconducting pseudo spin valves with engineered anisotropy. Physical Review B89, 140508(R) (2014).

Bobkova, I. V. & Bobkov, A. M. Recovering the superconducting state via spin accumulation above the pair-breaking magnetic field of superconductor/ferromagnet multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 84, 140508(R) (2011).

Bobkova, I. V. & Bobkov, A. M. Recovering of superconductivity in S/F bilayers under spin-dependent nonequilibrium quasiparticle distribution. Pis’ma v ZhETF 101, 442 (2015).

Nitta, J., Akazaki, T., Takayanagi, H. & Enoki, T. Gate control of spin-orbit interaction in an inverted In0.53Ga0.47As/In0.52Al0.48As Heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1335 (1997).

Engels, G., Lange, J., Schapers, T. & Luth, H. Experimental and theoretical approach to spin splitting in modulation-doped InxGa1–xAs/InP quantum wells for B→0. Phys. Rev. B 55, 1958 (1997).

Grundler, D. Large Rashba splitting in InAs quantum wells due to electron wave function penetration into the barrier layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 6074 (2000).

Liang, D. & Gao, X. P. A. Strong tuning of Rashba spin-orbit interaction in single InAs nanowires. Nano Lett. 12, 3263 (2012).

Giglberger, S. et al. Rashba and Dresselhaus spin splittings in semiconductor quantum wells measured by spin photocurrents. Phys. Rev. B 75, 035327 (2007).

Jacobsen, S. H., Ouassou, J. A. & Linder, J. Critical temperature and tunneling spectroscopy of superconductor-ferromagnet hybrids with intrinsic Rashba-Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 92, 024510 (2015).

Eschrig, M., Cottet, A., Belzig, W. & Linder, J. General boundary conditions for quasiclassical theory of superconductivity in the diffusive limit: application to strongly spin-polarized systems. New J. Phys. 17, 83037 (2015).

Chiba, D. et al. Electrical control of the ferromagnetic phase transition in cobalt at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 10, 853 (2011).

Cottet, A. Spectroscopy and critical temperature of diffusive superconducting/ferromagnetic hybrid structures with spin-active interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 76, 224505 (2007).

Jacobsen, S. H. & Linder, J. Giant triplet proximity effect in π-biased Josephson junctions with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 92, 024501 (2015).

Arjoranta, J. & Heikkilä, T. Intrinsic spin-orbit interaction in diffusive normal wire Josephson weak links: supercurrent and density of states. Phys. Rev. B 93, 024522 (2016).

Espedal, C., Yokoyama, T. & Linder, J. Anisotropic paramagnetic Meissner effect by spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 127002 (2016).

Mal’shukov, A. G. Nonlocal effect of a varying in-space Zeeman field on supercurrent and helix state in a spin-orbit-coupled s-wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054511 (2016).

Jacobsen, S. H., Kulagina, I. & Linder, J. Controlling superconducting spin flow with spin-flip immunity using a single homogeneous ferromagnet. Scientific Reports 6, 23926 (2016).

Schopohl, N. & Maki, K. Quasiparticle spectrum around a vortex line in a d-wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 52, 490 (1995); Schopohl, N. Transformation of the Eilenberger equations of superconductivity to a scalar Riccati equation. arXiv:cond-mat/9804064; Konstandin, A., Kopu, J. & Eschrig, M. Superconducting proximity effect through a magnetic domain wall. Phys. Rev. B72, 140501(R) (2005).

Singh, A., Voltan, S., Lahabi, K. & Aarts, J. Colossal proximity effect in a superconducting triplet spin valve based on the half-metallic ferromagnet CrO2 . Phys. Rev. X 5, 21019 (2015).

Houzet, M. & Meyer, J. S. Quasiclassical theory of disordered Rashba superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 014509 (2015).

Reeg, C. R. & Maslov, D. L. Proximity-induced triplet superconductivity in Rashba materials. Phys. Rev. B 92, 134512 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Niladri Banerjee for useful discussions. J.L. and J.A.O. acknowledge funding via the “Outstanding Academic Fellows” programme at NTNU, the COST Action MP-1201 and the Research Council of Norway Grant numbers 205591, 216700 and 240806. J.W.A.R. and A.D.B. acknowledge funding from the Leverhulme Trust (IN-2013-033), the Royal Society and the EPSRC through the Programme Grant “Superconducting Spintronics” (EP/N017242/1) and the Doctoral Training Grant (NanoDTC EP/G037221/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.O. and A.D.B. conceived the idea and J.A.O. performed the analytical and numerical calculations with support from J.L., J.A.O., A.D.B., J.W.A.R. and J.L. contributed to the discussion and writing of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ouassou, J., Di Bernardo, A., Robinson, J. et al. Electric control of superconducting transition through a spin-orbit coupled interface. Sci Rep 6, 29312 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29312

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29312

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.