Abstract

Mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have been developed to study the pathophysiology of amyloid β protein (Aβ) toxicity, which is thought to cause severe clinical symptoms such as memory impairment in AD patients. However, inconsistencies exist between studies using these animal models, specifically in terms of the effects on synaptic plasticity, a major cellular model of learning and memory. Whereas some studies find impairments in plasticity in these models, others do not. We show that long-term potentiation (LTP), in the CA1 region of hippocampal slices from this mouse, is impared at Tg2576 adult 6–7 months old. However, LTP is inducible again in slices taken from Tg2576 aged 14–19 months old. In the aged Tg2576, we found that the percentage of parvalbumin (PV)-expressing interneurons in hippocampal CA1-3 region is significantly decreased, and LTP inhibition or reversal mediated by NRG1/ErbB signaling, which requires ErbB4 receptors in PV interneurons, is impaired. Inhibition of ErbB receptor kinase in adult Tg2576 restores LTP but impairs depotentiation as shown in aged Tg2576. Our study suggests that hippocampal LTP reemerges in aged Tg2576. However, this reemerged LTP is an insuppressible form due to impaired NRG1/ErbB signaling, possibly through the loss of PV interneurons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Progressive loss of memory function and the accumulation of amyloid β protein (Aβ) in the brain are key characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology1,2. Previous findings have demonstrated that synaptic plasticity, regarded as the cellular basis for learning and memory3, is vulnerable to exposure to high levels of Aβ; hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) is impaired following exogenous exposure to soluble oligomeric Aβ4,5,6. To try to understand how memory function in AD becomes dysregulated, a vast number of studies have looked to determine the mechanisms underlying the Aβ-mediated impairment of synaptic plasticity.

To closely model AD pathology, transgenic mice carrying mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP), which causes excessive production of Aβ in the brain, have been developed, and are used to investigate the pathophysiology of Aβ toxicity7. However, inconsistencies remain in the pathological readouts from such animals; whether LTP is inhibited or normal in these mouse models remains unclear, as notably reported in papers using one of the most frequently used transgenic mice harboring the Swedish mutation in APP (APP695SWE)8,9. Here, whilst some studies report inhibition of LTP in the APP transgenic mouse10,11,12, others find no inhibition of LTP between 3 months and 12 months of age in these AD model mice13,14,15,16. An important aspect to consider in relation to this is the diverse ages of the animals used in these studies (ranging from 3 to 18 months of age). Here, some studies have reported a relationship between abnormal synaptic plasticity and the age of the APP transgenic mouse used, with young animals displaying profound LTP impairments that are not present in the older animals15,17. The reason for this apparent age-dependent effect, however, is unknown.

One explanation for these age-dependent effects could relate to the interneuronal control of pyramidal neurons. Most GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampal CA1 region innervate their synapses onto pyramidal cell dendrites where neuronal computation, such as modulation, integration of synaptic inputs and expression of synaptic plasticity, mainly occurs18,19,20. Recently, it was shown that loss of GABAergic interneurons leads to an enhanced LTP in the hippocampal CA1 region21. Interestingly, a significant decrease in the number of GABAergic interneurons was observed in the hippocampus of the AD mouse model and indeed in AD patients22,23. Furthermore, enhanced LTP was accompanied with reduced numbers of interneurons in the dentate gyrus of the mouse model of both amyloidosis and tauopathy24. One possible explanation, therefore, is that the age-dependent loss of GABAergic interneurons in the transgenic mice actually serves to facilitate the induction of LTP in the hippocampal CA1 region.

Both ErbB receptor kinases in GABAergic interneurons and the endogenous ligand neuregulin 1 (NRG1), a neurotropic factor implicated in neural development, neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity25, have been variously shown to regulate hippocampal LTP: (1) neutralization of endogenous NRG1 in the hippocampus enhances the magnitude of hippocampal LTP at CA1 region26, whereas addition of exogenous NRG1 suppresses the induction of LTP27,28; (2) inhibition of ErbB4 kinase increases the magnitude of hippocampal LTP, an effect similarly observed in ErbB4 knockout mice29,30; (3) ErbB4 is selectively expressed in interneurons but not in pyramidal neurons31, and ErbB4 deletion in parvalbumin (PV) interneurons, the major type of GABAergic interneurons in hippocampus32,33, completely blocks the LTP regulation induced by NRG126,30. Critically, NRG1 and ErbB4 distribution was found to be altered in the brains spotted with neuritic plaques in the mouse model of AD and in AD patients34. We therefore hypothesized that the age-dependent dysregulation of hippocampal LTP in the APP transgenic mouse was underpinned by the Aβ-mediated impairment of NRG1/ErbB signaling, leading to the facilitation of LTP. Here we demonstrate a possible link between a loss of interneurons, NRG1/ErbB signaling dysregulation and changes in synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of AD.

Results

The reemergence of LTP in the hippocampus of aged Tg2576

To examine whether LTP in Tg2576 mice is altered in an age-dependent manner, we compared LTP in two different age groups, 6–7 months old (adult) and 14–19 months old (aged), in the hippocampal CA1 region. Tg2576 is a well-documented mouse model of AD showing high levels of Aβ and memory impairment8,10, and soluble Aβ in the brains of these transgenic animals begins to be significantly accumulated at around 6 months of age after a non-accumulation phase from birth11,35. Increased fEPSP induced by high frequency stimulation (HFS) at the Schaffer collateral pathway was maintained for 2 hours in adult littermate WT, but returned to baseline levels in adult Tg2576 (Tg: 113.2 ± 7.4% of baseline, n = 8, closed circle; WT: 159.1 ± 9.4%, n = 8, open circle, P < 0.01 Fig. 1A), which is consistent with reports describing impaired LTP in Tg2576 of similar ages12,15. In contrast, the increased fEPSPs were maintained until 2 hours after HFS application in aged Tg2576, and there were no significant differences in the levels of the potentiated fEPSPs between the aged Tg2576 and littermate WT mice (Tg: 181.7 ± 12.0%, n = 7, closed circle; WT: 164.8 ± 7.2%, n = 7, open circle, P > 0.05, Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the observed time period for LTP inhibition and reappearance in Tg2576 mice is very similar to a previous report which pointed out that soluble Aβ levels in the brain was not correlated with the LTP deficit in aged animals15. Clearly, then, there is an interesting disparity in impaired synaptic plasticity in these AD mouse models; whilst LTP is inhibited at early ages after soluble Aβ accumulation begins, it reemerges at older ages.

(A) Applying two trains of tetanus stimuli (10 Hz in s, 3 s inter-train interval) to the Schaffer collateral pathway evoked LTP in the hippocampal CA1 region in 6–7 months old WT (open circle, n = 8) but did not in Tg2576, where the fEPSP was gradually decreased to the baseline level 2 hours after LTP induction by HFS (closed circle, n = 8). (B) In 14–19 months old animals, LTP was observed in both WT (open circle, n = 7) and Tg2576 (closed circle, n = 7) mice, and their increased fEPSP levels were not significantly different (P > 0.05). Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). fEPSP = field excitatory postsynaptic potential.

Decreased percentage of PV interneurons in hippocampal CA region of aged Tg2576

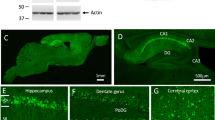

One possible explanation for the LTP reemergence in aged Tg2576 would be the decreased density of inhibitory interneurons in hippocampus, which could conceivably contribute to an enhancement of excitatory signaling and the facilitation of LTP. To test this hypothesis, we specifically measured the percentage of PV interneurons in hippocampal CA1-3 region. PV interneurons constitute a major proportion of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus32,33. Further, PV interneurons are critical for the NRG1/ErbB4-mediated down-regulation of LTP expression at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse26,30. PV-immunoreactive (IR) neurons were observed in hippocampus of both the adult and aged Tg2576 (Fig. 2A,B). To calculate the percentage of PV interneurons, NeuN and PV-IR neurons were counted in whole CA subfields, and the ratio of PV-IR to NeuN-IR cells was estimated. We found that the proportion of PV interneurons to NeuN-positive cells was significantly decreased in aged Tg2576 compared with adult Tg2576 (Fig. 2C). Importantly, this reduction was not solely due to the aging effect, since there was no significant difference in the percentage of the neurons between adult and aged littermate WT. Interestingly, it was recently shown that loss of PV interneurons is associated with enhanced LTP in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis36, suggesting a strong possibility of this neuronal loss enhancing LTP in aged Tg2576.

(A) Representative PV immunohistochemistry stains in the hippocampus of a 6–7 months old (adult) WT (n = 4) and Tg2576 (n = 4) mouse. PV-positive interneurons are shown in the hippocampus at a low magnification (original magnification, ×40), and at a closer distance from the CA1 (original magnification, ×100, pointed by arrowheads) and CA3 (original magnification, ×100). (B) Representative PV immunohistochemistry stains in the hippocampus of a 14–19 months old (aged) WT (n = 6) and Tg2576 (n = 6) mouse. (C) The ratio of PV-positive cells to NeuN-positive cells (data not shown) in aged Tg2576 is significantly lower than in adult Tg2576 (**P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001).

NRG1-induced LTP inhibition and depotentiation are impaired in aged Tg2576

We next tested whether the regulation of synaptic plasticity by NRG1/ErbB signaling is intact in aged Tg2576. Previous studies demonstrated that perfusion of hippocampal slices with recombinant NRG1 peptide inhibits the induction of hippocampal LTP by activating ErbB4 receptor kinase in PV interneurons26,30. We first measured hippocampal LTP in 2–4 months old (young) Tg2576, in which Aβ is produced only marginally in the brain35, and littermate WT. We found that LTP was readily induced in both age groups (Tg: 185.5 ± 11.2%, n = 7, closed circle; WT: 177.4 ± 10.3%, n = 7, open circle, P > 0.05, Fig. 3A). We next investigated the NRG1-induced LTP inhibition using those mice, by measuring fEPSP in hippocampal slices perfused with 1 nM NRG1 peptide, stimulated with HFS 20 minutes after onset of NRG1 perfusion. The NRG1 perfusion readily suppressed the induction of LTP in both young Tg2576 and littermate WT (Tg vehicle: 166.9 ± 13.6%, n = 7, grey closed circle; WT vehicle: 187.0 ± 17.0%, n = 6, grey open circle; Tg NRG1: 98.4 ± 6.4%, n = 6, maroon closed circle, P < 0.01 compared with Tg vehicle; WT NRG1: 111.0 ± 3.7%, n = 6, maroon open circle, P < 0.01 compared with WT vehicle, Fig. 3B). We then tested the integrity of NRG1-induced LTP inhibition in aged Tg2576 and littermate WT. Interestingly, we found that NRG1 perfusion inhibited LTP induction in aged WT, but did not in aged Tg2576 (Tg vehicle: 179.0 ± 15.3%, n = 5, grey closed circle; WT vehicle: 170.2 ± 16.1%, n = 6, grey open circle; Tg NRG1: 175.6 ± 14.1%, n = 6, maroon closed circle, P > 0.05 compared with Tg vehicle; WT NRG1: 112.7 ± 4.4%, n = 6, maroon open circle, P < 0.05 compared with WT vehicle, Fig. 3C). These data suggest that an NRG1/ErbB-mediated signaling pathway that can suppress LTP does not function normally in aged Tg2576 in which LTP reappears after the deficit period at adult age.

(A) LTP was readily induced in both 2–4 months old WT (open circle, n = 7) and Tg2576 (closed circle, n = 7) mice. (B) Perfusion of nM NRG1 peptide during the period indicated by the heavy line suppressed LTP in both 2–4 months old WT (maroon open circle, n = 6), and Tg2576 (maroon closed circle, n = 6). (C) NRG1 perfusion also suppressed LTP in 14–19 months old WT (maroon open circle, n = 6), but did not in Tg2576 (maroon closed circle, n = 6) (D) Applying theta pulse stimulation (TPS, 100 pulses with Hz) 5 minutes after HFS reversed LTP in both 2–4 months old WT (open circle, n = 6) and Tg2576 (closed circle, n = 7). (E) TPS also reversed LTP in 14–19 months old WT (open circle, n = 6), but did not in Tg2576 (closed circle, n = 6). (F) In both Tg2576 and WT mice, the expression of NRG1 and ErbB4 in the hippocampus was not significantly different among 3 aged groups (P > 0.05). However, this data showed that the expression of ErbB4 tended to decrease in Tg2576 (closed bar, n = 5) in comparison with littermate WT (open bar, n = 5) at each aged group. Two-way ANOVA and Turkey’s multiple comparison tests were used for the statistical analysis of this data. Error bars represent SEM. fEPSP = field excitatory postsynaptic potential.

NRG1/ErbB signaling is known to be involved in depotentiation, another form of synaptic plasticity where LTP can be reversed by a specific form of synaptic activity induced within a few minutes following LTP induction37,38. It has been shown that the application of NRG1 peptide or theta-pulse stimulation (TPS), a low frequency stimulation that is widely used to induce depotentiation37, reverses previously induced hippocampal LTP, and ErbB4 in PV interneurons is crucial for this effect30,39. To examine whether depotentiation is intact in both young and aged Tg2576, we applied TPS to the Schaffer collateral pathway in the hippocampus 5 minutes after HFS application. We found that potentiated fEPSPs by HFS application returned to the baseline at 1.5 hours after applying TPS in both young Tg2576 and littermate WT, indicative of a depotentiation of synapses (Tg: 118.3 ± 7.0%, n = 7, closed circle; WT: 103.8 ± 8.3%, n = 6, open circle, P > 0.05, Fig. 3D). LTP was also readily depotentiated by the application of TPS in aged littermate WT, but remained at an elevated level 2 hours after applying TPS in aged Tg2576 (Tg: 178.4 ± 13.7%, n = 6, closed circle; WT: 104.7 ± 5.0%, n = 6, open circle, P < 0.01, Fig. 3E). The absence of depotentiation in slices from aged Tg2576 animals is consistent with NRG1/ErbB signaling being impaired in aged Tg2576, and suggests that synaptic function in aged Tg2576 is abnormal in spite of the reemergence of LTP. We also observed that, in both Tg2576 and WT mice, the expression of NRG1 and ErbB4 in the hippocampus was not significantly different among 3 age groups (P > 0.05). However, this data showed that the expression of ErbB4 tended to decrease in Tg2576 in comparison with littermate WT (Tg: 78 ~ 82%, n = 5, closed bar, P > 0.05, Fig. 3F).

Inhibition of ErbB receptor kinase in adult Tg2576 can mimic the changes of the synaptic plasticity in aged Tg2576

If the impaired NRG1/ErbB signaling is actually correlated with the reemerged LTP in aged Tg2576 mice, disrupting NRG1/ErbB signaling in adult Tg2576 might induce similar synaptic characteristics to those observed in aged Tg2576: normal LTP but impaired depotentiation. We therefore investigated the effect of blocking the ErbB4 receptor on synaptic plasticity in adult Tg2576. To do this, we first perfused hippocampal slices from adult Tg2576 with 10 μM PD158780, an inhibitor of ErbB receptor kinase, for 10 minutes starting 2 minutes before HFS application. LTP was induced in PD158780 treated slices, and the potentiated fEPSP was maintained for more than 2 hours (Tg vehicle: 108.8 ± 8.8%, n = 6, grey closed circle; WT vehicle: 146.4 ± 6.7%, n = 3, grey open circle; Tg PD158780: 154.6 ± 3.9%, n = 6, maroon closed circle, P < 0.01 compared with Tg vehicle, WT PD158780: 176.2 ± 2.8%, n = 6, maroon open circle, P < 0.05 compared with WT vehicle, Fig. 4A). Interrupting endogenous NRG1/ErbB signaling by PD158780 is also known to enhance the level of fEPSPs at already potentiated synapses39. We therefore tested whether PD158780 perfusion after LTP induction could rescue the LTP deficit in adult Tg2576. Perfusion of 10μΜ PD158780 for an hour after LTP induction increased the level of diminishing LTP and the re-potentiated fEPSPs were maintained for another 2 hours (Tg PD158780: 168.7 ± 16.1%, n = 6, closed circle, Fig. 4B). Therefore, disrupted NRG1/ErbB signaling might be sufficient to induce LTP in aged Tg2576 as impaired LTP was rescued in adult Tg2576 upon the perfusion of PD158780 at both HFS induction and an hour followed by the induction. In addition, we measured TPS-induced depotentiation in conjunction with 10 minutes PD158780 perfusion begun 2 minutes before HFS application. We found that LTP could not be depotentiated by the TPS application in the PD158780 treated slices (Tg vehicle: 120.2 ± 8.5%, n = 5, grey closed circle; Tg PD158780: 200.5 ± 30.4%, maroon closed circle, n = 6, P < 0.05, Fig. 4C) but readily depotentiated in littermate WT mice (WT: 120.6 ± 5.6%, n = 5, open circle, Fig. 4D). These data suggest that the inhibition of NRG1/ErbB signaling in adult Tg2576 is sufficient to mimic the characteristics of hippocampal synaptic plasticity in aged Tg2576.

(A) Perfusion of 10 μM PD158780, an inhibitor of ErbB, for 10 minutes starting two minutes before HFS, as indicated by the heavy line, restored LTP in 6–7 months old Tg2576 (maroon closed circle, n = 6), and enhanced LTP in 6–7 months old wild-type (maroon open circle, n = 6). (B) Perfusion of PD158780 for 10 minutes starting an hour after HFS increased fEPSP slope, which was continuously decreased just before, and the re-potentiated fEPSP slope was maintained for another two hours. (closed circle, n = 6) (C) TPS did not reverse LTP in the hippocampal slices from 6–7 months old Tg2576 perfused with PD158780 (closed circle, n = 6). (D) TPS readily reversed LTP in 6–7 months old WT slices (open circle, n = 5). Error bars represent SEM. fEPSP = field excitatory postsynaptic potential.

Deficits in memory function in aged Tg2576

To assess whether learning and memory function changed during ageing in Tg2576 animals, we conducted a novel object recognition memory test. In all experimental conditions, total exploration time was not different between groups (training, Fig. 5A; test, Fig. 5B). However, the discrimination index indicates impaired object recognition memory in both groups of 6 month- and 13 month-old Tg2576 mice. Novel object recognition memory performance declined progressively during aging in Tg2576 mice compared with WT littermate mice (Fig. 5C).

Habituation training was conducted for 3 days by exposing the animal to the experimental apparatus for 10 min per day in the absence of objects for the indicated number of days. The training session was conducted 24 h following the last habituation training. During the training session, mice were placed in the experimental apparatus in the presence of two identical objects and allowed to explore for 10 min. After a retention interval of 24 h, mice were again placed in the apparatus; however, one of the objects was replaced with a novel one. Mice were allowed to explore for 10 min. (A) Total exploration time in training session. (B) Total exploration time in test session. (C) Discrimination index in test session. Adult Tg2576 (Tg) mice displayed a significant reduction in object recognition memory compared with wild-type (WT) mice (24.3 vs 39.1 at 6 months, 16.7 vs 35.2 at 13 months). Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05 (n = 7–10/group, t-test).

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that the number of PV interneurons is significantly reduced in the hippocampus of the aged Tg2576. Critically, we reveal that NRG1/ErbB4 signaling-mediated LTP regulation, TPS-induced depotentiation and NRG1-induced LTP suppression, for which PV interneurons are essential, are impaired in the aged Tg2576. An inhibitor of the ErbB receptor prevented the LTP deficit but blocked TPS-induced depotentiation in the adult Tg2576, suggesting that the disrupted NRG1/ErbB signaling would be a strong candidate for the cause of the LTP reemergence in aged Tg2576. Our results may contribute to a potential answer to the controversy over whether LTP is inhibited10,11,12 or normal13,14,15,16 in the transgenic mouse model of AD (expressing APPswe mutation): LTP is only hindered for a certain period of time and then reappears in spite of concomitant behavioral deficits at that time, but the revived LTP is still abnormal due to the lack of inhibitory control and is accompanied by learning and memory deficits. Accordingly, this could account for the observed LTP found in certain AD transgenic mice13,14,15,16; LTP is indeed inducible, but the fundamental molecular mechanisms responsible for its induction and expression have actually changed. Indeed, evidence suggests that LTP impairment is associated with behavioral deficits but the degree of LTP impairment is not related to the accumulation of Aβ and age from 3 to 12 months16.

Among the observed changes in aged Tg2576, loss of interneurons in the AD brain has attracted many investigators’ attention to examine the physiological consequences of the cell loss and its relevance to AD. Several studies reported that GABAergic interneurons are more vulnerable to the toxic oligomeric Aβ than pyramidal neurons23,40, and are observed to degenerate in the transgenic mouse model of tauopathy41 or both amyloidosis and tauopathy24, as well as in human apolipoprotein E4 knock-in mouse42 and in AD patients22. Interneuron degeneration in the AD mouse models led to alterations in synaptic plasticity24,41, stereotypic hyperactivity24, inhibited sensory motor gating41, and impaired learning and memory41,42. In addition, recent studies have shown that both hormonal intervention and transplantation of interneuron progenitors to prevent or replace GABAergic interneuronal loss in AD mouse models could restore memory and prevent cognitive dysfunctions which are usually observed in the transgenic mice43,44. Thus, loss of interneurons is a relatively established pathological change and a direct cause of cognitive and behavioral abnormalities in AD. Our finding that PV interneurons degenerates in the hippocampus of aged Tg2576 showing abnormal synaptic plasticity also supports this notion.

On the other hand, the relationship between NRG1/ErbB signaling and AD has just started to be examined. NRG1/ErbB signaling has recently been implicated in several neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, because of its importance in development and function of neural circuitry, relevant to behavioral deficits and genetic association with those diseases45. There was also a polymorphism study suggesting that the NRG1 gene is associated with AD46, (though see47). Some recent studies reported that, in the brains of both human and AD mouse models, expression levels of NRG1 and ErbB4 were changed48,49 and the distribution of those proteins in the hippocampus was altered along accumulated neuritic plaques34. However, further investigation is required to determine whether changes in NRG1 and ErbB expression actually contribute to the progression of AD. Interestingly, some studies have shown that pathophysiological features of AD can be remedied by modulating NRG1/ErbB4 signaling; treatment of NRG1 in APP/PS1 transgenic mice inhibits neuronal apoptosis in APP/PS1 transgenic mice via ErbB4-dependent PI3-kinase/Akt pathway activation49, and also prevents soluble Aβ1-42-induced LTP impairment via ErbB4 activation50. Collectively, therefore, although there are still only limited studies, NRG1 and ErbB kinases may play an important role in AD and other neurodegenerative disorders. In accordance with this, we also showed that NRG1/ErbB signaling was interrupted in the aged AD mouse model, as treatment of NRG1 did not suppress LTP in hippocampus of the aged Tg2576. This may be due to loss of PV interneurons, as NRG1 suppress LTP via activating ErbB4 receptor kinase in the specific neuron. We found that the percentage of PV interneurons in hippocampal CA region of aged Tg2576 was only about 70% of the percentage in adult Tg2576 and 50% in aged littermate WT. A direct relationship, however, between disruption of NRG1/ErbB4 signaling and loss of PV interneuron in aged AD mouse models, should be investigated in future studies.

Lastly, as far as we know, activity-dependent depotentiation in AD mouse model has not been previously measured. Along with LTP and long-term depression (LTD), depotentiation has been regarded as another important type of synaptic plasticity38. Acting as a counterbalance to the potential saturation of synaptic potentiation, depotentiation may contribute to synaptic homeostasis by which synaptic strength is maintained at a set level to be changeable by subsequent neuronal activity. In addition, depotentiation has been shown to play an important role in the refinement of developing neural circuits51, storage of novel spatial information52 and fear memory extinction in amygdala53. Clearly, then, depotentiation plays a critical role in normal physiological function. In this study, we observed that depotentiation could not be induced in aged Tg2576. This means that synaptic memory is still ablated in the aged Tg2576 in spite of the reemergence of LTP. Given that it has been suggested that depotentiation is related to specific neurological diseases and involves molecular mechanisms distinct from LTP and LTD54, it is reasonable to assume that Tg2576 would exhibit different behavioral phenotypes at specific ages when LTP and depotentiation emerge dysregulated. Indeed, previous reports suggest that aged human APP transgenic mice exhibited behavioral abnormalities such as hyperactivity55,56,57,58 and deficits in sensorimotor gating measured by prepulse inhibition (PPI)59, which are similar to those shown in the transgenic animals where depotentiation was not induced and NRG1/ErbB signaling impaired30. Such activity disturbance and PPI deficits are also observed in AD patients60,61. However, further study is needed to directly demonstrate the relationship between impaired depotentiation and the behavioral abnormalities in Tg2576 or other AD mouse models, such as the deficits in learning and memory paradigms like those we demonstrate here. This will give us further insight into the behaviorally relevant synaptic level changes occurring during the development of AD pathology. In summary, our three new findings of reduced proportion of hippocampal PV interneurons, disruption of NRG1/ErbB4 signaling and impaired depotentiation, in aged Tg2576, might shed light on the underlying pathological changes altering synaptic memory during the progress of AD.

Methods

Materials

Recombinant human NRG1-beta1 epidermal growth factor (EGF) domain (R&D Systems, #396-HB-050) was reconstituted in sterile PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma, #A3294). ErbB receptor kinase inhibitor PD158780 (Calbiochem, #513035) was dissolved at 10 mM in DMSO for stock solution.

Animals

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Tg2576 male mice were received from Taconic (USA, #1349) and crossbred with hybrid B6SJLF1 (from Taconic) female mice. The offspring, heterozygous transgenic and littermate wild type (WT) male mice, were used. The mice were housed in individual ventilated cages (IVC) with access to water and food ad libitum, under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle.

Hippocampal slice preparation

Animals were sacrificed with cervical dislocation and decapitated. The brain was rapidly removed and one hemisphere was directly placed into ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4 and 10 mM D-Glucose, perfused with gas consisting of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The other hemisphere was used for immunohistochemistry. The hippocampus was extracted and transverse hippocampal slices (40 μm thickness) were cut using a McIllwain tissue chopper (Mickle Laboratory Engineering Co.). Following manual separation, the slices were submerged in aCSF for a minimum of 1 hour for recovery before experiments commenced.

Electrophysiology

Hippocampal slices were placed into the recording chamber, continuously perfused with oxygenated aCSF flowing at a rate of at ml min−1, maintained at a temperature of 29–30 °C. For recording, two stimulating electrode were positioned on Schaffer collateral pathway (for LTP and depotentiation input) and subiculum region (for control input) respectively, to produce field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSP). Recording glass pipettes were prepared by a micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument, P-1000) and filled with M NaCl. The recording glass pipettes were fixed and controlled by a micromanipulator, used to locate the recording electrode to the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Following the acquisition of a stable baseline for 30 minutes, two trains of tetanus stimuli (100 Hz for 1 second with 30 seconds inter-tetanus interval) were applied to induce LTP. Depotentiation was induced with theta pulse stimulation (5 Hz for 1 minute) 5 minutes following the induction of LTP. Data acquisition and analysis was performed using WinLTP (www.winltp.com). Briefly, the slope of the evoked fEPSPs was measured, normalized to the pre-conditioning baseline and expressed as a percentage of baseline.

Western blot analysis

Hippocampal slices were homogenized, lysed and immediately snap frozen. Protein samples were separated according to their size on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were probed with primary antibodies against NRG1 (Abcam, #ab53104) and ErbB4 (Thermo Scientific Pierce, #MAI-861) overnight and then probed with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for an hour. Immunoreactive bands were detected using an ECL detection system (LAS-3000, FUJIFILM, Japan). Optical densities of the band were quantified using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nig.gov/ij/).

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse hemispheric brains were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 3 days. Brains were dissected, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin for histopathological evaluation. Tissue blocks were sliced at a thickness of 4 μm for immunohistochemistry. Each unstained slide was stained with specific antibodies against Parvalbumin (Product No. PA1-933, 1:1000, ThermoFisher, Rockford, IL, USA) and NeuN (Product No. MAB377, 1:100, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) using an automated immunostainer (Bond-maX DC2002, Leica Biosystems, Bannockburn, IL, USA). Programmed heat-induced epitope retrieval was carried out using bond epitope retrieval solution 1 (containing Tris EDTA, pH 9.0) for Parvalbumin antibody and bond epitope retrieval solution 2 (containing Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) buffer at pH 9.0) for NeuN antibody. Negative controls were processed similarly in the absence of primary antibodies.

Object recognition memory test

The experimental apparatus consisted of a black polyvinyl plastic square open field (45 cm × 45 cm × 45 cm). Habituation training was conducted for 3 days by exposing the animal to the experimental apparatus for 10 min per day in the absence of objects for the indicated number of days. The training session was conducted 24 h following the last habituation training. During the training session, mice were placed in the experimental apparatus in the presence of two identical objects and allowed to explore for 10 min. After a retention interval of 24 h, mice were again placed in the apparatus; however, one of the objects was replaced with a novel one. Mice were allowed to explore for 10 min. The objects chosen for this experiment included a plastic orange and wooden trigonal prism, both approximately the same height. The durations of time mice spent exploring each object (familiar object, Tfamiliar; novel object, Tnovel) were recorded. The discrimination index was calculated by following formula: (Tnovel − Tfamiliar)/(Tnovel + Tfamiliar) × 100.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed from one slice per mouse (n = number of slices = number of mice). In electrophysiology, the fEPSP slope was expressed as the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean) and relative to a normalized baseline. For the comparison of LTP and depotentiation between groups, fEPSPs at the end of recording were used. An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for the statistical analysis of the electrophysiology data and novel object recognition tests, and two-way ANOVA and Turkey’s multiple comparison tests for the Western blotting and immunohistochemistry data. All statistical calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Huh, S. et al. The reemergence of long-term potentiation in aged Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Sci. Rep. 6, 29152; doi: 10.1038/srep29152 (2016).

References

Gomez-Isla, T. et al. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of neurology 41, 17–24, doi: 10.1002/ana.410410106 (1997).

Hardy, J. & Selkoe, D. J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356, doi: 10.1126/science.1072994 (2002).

Bliss, T. V. P. & Collingridge, G. L. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 361, 31–39 (1993).

Walsh D. M., Fadeeva, K. I., Cullen, J. V., Anwyl, W. K., Wolfe, R., Rowan, M. S. & Selkoe, M. J. DJ Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo . Nature 416 (2002).

Klyubin, I. et al. Amyloid beta protein immunotherapy neutralizes Abeta oligomers that disrupt synaptic plasticity in vivo . Nat. Med. 11, 556–561, doi: 10.1038/nm1234 (2005).

Shankar, G. M. et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 14, 837–842, doi: 10.1038/nm1782 (2008).

Gotz, J. & Ittner, L. M. Animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 532–544, doi: 10.1038/nrn2420 (2008).

Hsiao, K. et al. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 274, 99–102 (1996).

Irizarry, M. C., McNamara, M., Fedorchak, K., Hsiao, K. & Hyman, B. T. APPSw transgenic mice develop age-related A beta deposits and neuropil abnormalities, but no neuronal loss in CA1. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 56, 965–973 (1997).

Chapman, P. F. et al. Impaired synaptic plasticity and learning in aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 271–276 (1999).

Jacobsen, J. S. et al. Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 5161–5166, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600948103 (2006).

Balducci, C. et al. The gamma-secretase modulator CHF5074 restores memory and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in plaque-free Tg2576 mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 24, 799–816, doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101839 (2011).

Fitzjohn, S. M. et al. Age-related impairment of synaptic transmission but normal long-term potentiation in transgenic mice that overexpress the human APP695SWE mutant form of amyloid precursor protein. J. Neurosci. 21, 4691–4698 (2001).

Brown, J. T., Richardson, J. C., Collingridge, G. L., Randall, A. D. & Davies, C. H. Synaptic transmission and synchronous activity is disrupted in hippocampal slices taken from aged TAS10 mice. Hippocampus 15, 110–117, doi: 10.1002/hipo.20036 (2005).

Townsend, M. et al. Oral treatment with a gamma-secretase inhibitor improves long-term potentiation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 333, 110–119, doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.163691 (2010).

Volianskis, A., Kostner, R., Molgaard, M., Hass, S. & Jensen, M. S. Episodic memory deficits are not related to altered glutamatergic synaptic transmission and plasticity in the CA1 hippocampus of the APPswe/PS1deltaE9-deleted transgenic mice model of ss-amyloidosis. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 1173–1187, doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.005 (2010).

Larson, J., Lynch, G., Games, D. & Seubert, P. Alterations in synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices from young and aged PDAPP mice. Brain Res. 840, 23–35 (1999).

Häusser, M., Spruston, N. & Stuart, G. J. Diversity and dynamics of dendritic signaling. Science 290, 739–744 (2000).

Spruston, N. Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 9, 206–221, doi: 10.1038/nrn2286 (2008).

Klausberger, T. GABAergic interneurons targeting dendrites of pyramidal cells in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci 30, 947–957, doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06913.x (2009).

Howard, M. A., Rubenstein, J. L. & Baraban, S. C. Bidirectional homeostatic plasticity induced by interneuron cell death and transplantation in vivo . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 492–497, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307784111 (2014).

Takahashi, H. et al. Hippocampal interneuron loss in an APP/PS1 double mutant mouse and in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain struc. Funct. 214, 145–160, doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0242-4 (2010).

Krantic, S. et al. Hippocampal GABAergic neurons are susceptible to amyloid-beta toxicity in vitro and are decreased in number in the Alzheimer’s disease TgCRND8 mouse model. J. Alzheimers Dis. 29, 293–308, doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110830 (2012).

Loreth, D. et al. Selective degeneration of septal and hippocampal GABAergic neurons in a mouse model of amyloidosis and tauopathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 47, 1–12, doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.011 (2012).

Mei, L. & Xiong, W. C. Neuregulin 1 in neural development, synaptic plasticity and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 437–452, doi: 10.1038/nrn2392 (2008).

Chen, Y. J. et al. ErbB4 in parvalbumin-positive interneurons is critical for neuregulin 1 regulation of long-term potentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 21818–21823 (2010).

Huang, Y. Z. et al. Regulation of neuregulin signaling by PSD-95 interacting with ErbB4 at CNS synapses. Neuron 26, 433–455 (2000).

Ma, L. et al. Ligand-dependent recruitment of the ErbB4 signaling complex into neuronal lipid rafts. J. Neurosci. 23, 3164–3175 (2003).

Pitcher, G. M., Beggs, S., Woo, R. S., Mei, L. & Salter, M. W. ErbB4 is a suppressor of long-term potentiation in the adult hippocampus. Neurorep. 19, 139–143, doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f3da10 (2008).

Shamir, A. et al. The importance of the NRG-1/ErbB4 pathway for synaptic plasticity and behaviors associated with psychiatric disorders. J. Neurosci. 32, 2988–2997, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-11.2012 (2012).

Fazzari, P. et al. Control of cortical GABA circuitry development by Nrg1 and ErbB4 signalling. Nature 464, 1376–1380, doi: 10.1038/nature08928 (2010).

Wonders, C. P. & Anderson, S. A. The origin and specification of cortical interneurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 687–696, doi: 10.1038/nrn1954 (2006).

Bezaire, M. J. & Soltesz, I. Quantitative assessment of CA1 local circuits: knowledge base for interneuron-pyramidal cell connectivity. Hippocampus 23, 751–785, doi: 10.1002/hipo.22141 (2013).

Chaudhury, A. R. et al. Neuregulin-1 and ErbB4 immunoreactivity is associated with neuritic plaques in Alzheimer disease brain and in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 62, 42–54 (2003).

Kawarabayashi, T. et al. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid β protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease J. Neurosci. 21, 372–381 (2001).

Nistico, R. et al. Inflammation subverts hippocampal synaptic plasticity in experimental multiple sclerosis. PloS one 8, e54666, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054666 (2013).

Stäubli, U. & Chun, D. Factors regulating the reversibility of Long-Term Potentiation. J. Neurosci. 16, 853–860 (1996).

Huang, C. C. & Hsu, K. S. Progress in understanding the factors regulating reversibility of long-term potentiation. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 51–68 (2001).

Kwon, O. B., Longart, M., Vullhorst, D., Hoffman, D. A. & Buonanno, A. Neuregulin-1 reverses long-term potentiation at CA1 hippocampal synapses. J. Neurosci. 25, 9378–9383, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2100-05.2005 (2005).

Ramos, B. et al. Early neuropathology of somatostatin/NPY GABAergic cells in the hippocampus of a PS1xAPP transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 1658–1672, doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.022 (2006).

Levenga, J. et al. Tau pathology induces loss of GABAergic interneurons leading to altered synaptic plasticity and behavioral impairments. Acta Neuropathol. Comm. 1, 34, doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-34 (2013).

Andrews-Zwilling, Y. et al. Apolipoprotein E4 causes age- and Tau-dependent impairment of GABAergic interneurons, leading to learning and memory deficits in mice. J. Neurosci. 30, 13707–13717, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4040-10.2010 (2010).

Ma, K. & McLaurin, J. alpha-Melanocyte stimulating hormone prevents GABAergic neuronal loss and improves cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 34, 6736–6745, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5075-13.2014 (2014).

Tong, L. M. et al. Inhibitory interneuron progenitor transplantation restores normal learning and memory in ApoE4 knock-in mice without or with Abeta accumulation. J. Neurosci. 34, 9506–9515, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0693-14.2014 (2014).

Mei, L. & Nave, K. A. Neuregulin-ERBB signaling in the nervous system and neuropsychiatric diseases. Neuron 83, 27–49, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.007 (2014).

Go, R. C. et al. Neuregulin-1 polymorphism in late onset Alzheimer’s disease families with psychoses. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 139B, 28–32, doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30219 (2005).

Middle, F. et al. No association between neuregulin 1 and psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Alzheimers Dis. 20, 561–567, doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1405 (2010).

Woo, R. S., Lee, J. H., Yu, H. N., Song, D. Y. & Baik, T. K. Expression of ErbB4 in the neurons of Alzheimer’s disease brain and APP/PS1 mice, a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Anat. Cell Biol. 44, 116–127, doi: 10.5115/acb.2011.44.2.116 (2011).

Cui, W. et al. Neuregulin1beta1 antagnozies apoptosis via ErbB4-dependent activation of PI3-kinase/Akt in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurochem. Res. 38, 2237–2246, doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1131-z (2013).

Min, S. S. et al. Neuregulin-1 prevents amyloid β-induced impairment of long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices via ErbB4. Neurosci. Lett. 505, 6–9, doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.246 (2011).

Zhou, Q. & Poo, M. M. Reversal and consolidation of activity-induced synaptic modifications. Trends Neurosci. 27, 378–383, doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.006 (2004).

Qi, Y., Hu, N. W. & Rowan, M. J. Switching off LTP: mGlu and NMDA receptor-dependent novelty exploration-induced depotentiation in the rat hippocampus. Cerebral Cortex 23, 932–939, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs086 (2013).

Kim, J. et al. Amygdala depotentiation and fear extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 20955–20960, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710548105 (2007).

Sanderson, T. M. Molecular mechanisms involved in depotentiation and their relevance to schizophrenia. Chonnam Med. J. 48, 1–6, doi: 10.4068/cmj.2012.48.1.1 (2012).

Lalonde, R., LEwis, T. L., Strazielle, C., Kim, H. & Fukuchi, K. Transgenic mice expressing the βAPP695SWE mutation: effects on exploratory activity, anxiety, and motor coordination. Brain Res. 977, 38–45 (2003).

Ognibene, E. et al. Aspects of spatial memory and behavioral disinhibition in Tg2576 transgenic mice as a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 156, 225–232, doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.028 (2005).

Walter, A. et al. Motor impulsivity in APP-SWE mice: a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Behav. Pharmacol. 17, 525–533 (2006).

Fonseca, M. I. et al. Treatment with a C5aR antagonist decreases pathology and enhances behavioral performance in murine models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Immunol. 183, 1375–1383, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901005 (2009).

Esposito, L. et al. Reduction in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase modulates Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and accelerates the onset of behavioral changes in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 26, 5167–5179, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0482-06.2006 (2006).

Volicer, L., Harper, D. G., Manning, B. C., Goldstein, R. & Satlin, A. Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psych. 158, 704–711 (2001).

Ueki, A., Goto, K., Sato, N., Iso, H. & Morita, Y. Prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle response in mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia of Alzheimer type. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 60, 55–62 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning NRF-2014M3C7A1046041 (B.K.) and a grant from Chonnam National University Hospital CRI 13902-22.4 (B.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H., D.J.W. and B.C.K. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. K.L. performed the immunohistochemistry. S.H., S.B., S.C., D.K., K.L. and J.J. performed the experiments. S.H., M.P. and B.K. analyzed the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Huh, S., Baek, SJ., Lee, KH. et al. The reemergence of long-term potentiation in aged Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Sci Rep 6, 29152 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29152

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29152

This article is cited by

-

Fast-spiking parvalbumin-positive interneurons in brain physiology and Alzheimer’s disease

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Naturally-aged microglia exhibit phagocytic dysfunction accompanied by gene expression changes reflective of underlying neurologic disease

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Tau- but not Aß -pathology enhances NMDAR-dependent depotentiation in AD-mouse models

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.