Abstract

Experiments and computer simulations are carried out to investigate phase separation in a granular gas under vibration. The densities of the dilute and the dense phase are found to follow a lever rule and obey an equation of state. Here we show that the Maxwell equal-areas construction predicts the coexisting pressure and binodal densities remarkably well, even though the system is far from thermal equilibrium. This construction can be linked to the minimization of mechanical work associated with density fluctuations without invoking any concept related to equilibrium-like free energies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many-particle systems driven far from equilibrium, which occur abundantly in nature, technology, as well as in laboratory settings, often exhibit remarkable collective behaviour1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, such as clustering, swarming, or laning. In spite of the importance of such phenomena, the search for underlying principles governing their dynamics and emerging patterns is still continuing9,10,11,12. Inspired by analogous problems in equilibrium thermodynamics, it has proven useful to study non-equilibrium steady states (NESS) which are characterized by time-independent, non-trivial macroscopic quantities (and their fluctuations), such as the pressure and densities in a phase separated system.

A paradigmatic system exhibiting such a NESS is a driven granular gas13,14,15,16. In its simplest form, a granular gas is a cloud of noncohesive, dissipative spherical particles, maintained in a steady state by a continuous external drive17,18. The degree of dissipation is quantified by the restitution coefficient,  , which denotes the ratio of the relative normal speeds of particles after/before a collision. Whenever ε < 1, one observes clustering in a freely cooling system, or phase separation if energy is continuously supplied. Recent work has demonstrated that loosely confined grains driven by a periodic external force can separate into liquid- and gas-like phases via spinodal decomposition19. A related two-dimensional system driven by a thermal wall also exhibits behaviour similar to the phase separation in a van der Waals gas19,20,21,22,23. Consequently, concepts borrowed from equilibrium statistical physics were used to describe its phase separation20,21,22,24. To date, investigations were limited to a parameter space very close to the elastic limit. In this limit it has been suggested that thermodynamic concepts are generally applicable, including a phenomenological ‘free energy’ based on a Landau expansion21. However, away from the elastic limit its behaviour is expected to differ, since some basic assumptions of equilibrium statistical physics, such as detailed balance, are no longer valid.

, which denotes the ratio of the relative normal speeds of particles after/before a collision. Whenever ε < 1, one observes clustering in a freely cooling system, or phase separation if energy is continuously supplied. Recent work has demonstrated that loosely confined grains driven by a periodic external force can separate into liquid- and gas-like phases via spinodal decomposition19. A related two-dimensional system driven by a thermal wall also exhibits behaviour similar to the phase separation in a van der Waals gas19,20,21,22,23. Consequently, concepts borrowed from equilibrium statistical physics were used to describe its phase separation20,21,22,24. To date, investigations were limited to a parameter space very close to the elastic limit. In this limit it has been suggested that thermodynamic concepts are generally applicable, including a phenomenological ‘free energy’ based on a Landau expansion21. However, away from the elastic limit its behaviour is expected to differ, since some basic assumptions of equilibrium statistical physics, such as detailed balance, are no longer valid.

Here we investigate both experimentally and by computer simulations the phase separation behaviour of driven granular gases far away from the elastic limit, down to ε = 0.65. We demonstrate that not only can a Maxwell equal-areas construction predict the coexistence pressure and binodal densities remarkably well, but that such a construction can be applied, with reasonable accuracy, away from the critical point and for high dissipation. We argue that this construction can be traced to the minimisation of mechanical work associated with density fluctuations. Although the deviations from an exact Maxwell construction are small, we show their significance and provide a tentative interpretation.

Results

Pressure characteristics

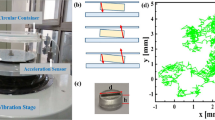

We study a system of approximately monodisperse spheres with diameter d = 610 μm, confined between two horizontal plates separated by a distance of 10 mm and driven vertically by a sinusoidal motion with amplitude A. We measured density profiles for the coexisting liquid-gas phase separation by using the long-cell apparatus described in the methods section. The results are shown in the insets in Fig. 1 and the corresponding liquid fractions are shown in the main panel. As the number of particles in the system (and hence the mean density  ) is increased, the volume of the liquid phase increases, moving the interface to the left. The densities ϕl and ϕg appear to be independent of

) is increased, the volume of the liquid phase increases, moving the interface to the left. The densities ϕl and ϕg appear to be independent of  . In the main panel the linear fits demonstrate that the system obeys a lever rule,

. In the main panel the linear fits demonstrate that the system obeys a lever rule,  , where fl is the liquid fraction and fg is the gas fraction. The lever rule confirms that there is an intrinsic mechanism which selects the liquid and gas densities as intensive quantities of the system.

, where fl is the liquid fraction and fg is the gas fraction. The lever rule confirms that there is an intrinsic mechanism which selects the liquid and gas densities as intensive quantities of the system.

Main panel: The open and filled symbols represent the interface position as obtained from the experiment and the simulations, respectively.

Dashed lines are linear fits to the data. Zero liquid fraction corresponds to gas density, ϕg, unity liquid fraction represents liquid density, ϕl (circles). Insets: The top inset shows the mean grey level from photographs of the experiment, presented in arbitrary units. Data are shown for densities in the range  , increasing from right to left. The driving amplitude is A = 2.1d. The bottom inset shows the density profiles obtained from simulations. Data are shown for densities in the range

, increasing from right to left. The driving amplitude is A = 2.1d. The bottom inset shows the density profiles obtained from simulations. Data are shown for densities in the range  .

.

In order to get access to quantities which are not readily available experimentally, we performed time-driven molecular dynamics simulations of our system. We relax the system for a sufficient amount of time (ten seconds of simulated time was found appropriate) to ensure we have reached the steady state. The pressure, for example, is then determined by averaging both spatially and over ten distinct initial configurations, for ten seconds each. We define the pressure in the homogeneous regions to be the average of the trace of the horizontal components of the pressure tensor25. To obtain the distribution of local pressures, we coarse-grain the system using bins of length 5d. Varying the bin size in a sensible range does not affect the results reported here.

By simulating small sample cells with horizontal dimensions less than the liquid-gas interface width, phase separation can be suppressed. In this way the pressure can be calculated as a function of homogeneous quantities even under conditions for which a large system would phase separate. Periodic boundary conditions are used in the horizontal directions. This method has previously been employed to obtain the equation of state for granular gases20,23,26,27,28. However, recent work for systems in thermal equilibrium questions whether the non-monotonic pressure-volume curves obtained represent the equation of state for the system, or merely reflect finite size effects29,30. In the following paragraphs we will demonstrate that P(v) does indeed serve as the equation of state for our granular system.

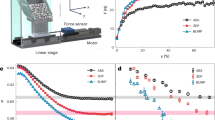

Figure 2 shows the dependence of P on the dimensionless volume per particle,  , in a small square-base cell of side L = 20d for A = 2.1d (solid line). As expected, the pressure exhibits a non-monotonic dependence on the volume, similar to that which is observed in a molecular fluid. Significantly, we find that for sufficiently small cells (

, in a small square-base cell of side L = 20d for A = 2.1d (solid line). As expected, the pressure exhibits a non-monotonic dependence on the volume, similar to that which is observed in a molecular fluid. Significantly, we find that for sufficiently small cells ( ) the calculated pressure is not a function of the system size.

) the calculated pressure is not a function of the system size.

The solid line shows the pressure, P(v), calculated from simulations of a small square-base cell with side length L = 20d.

In the unstable region, the pressure tends towards the dashed tie line which connects the binodal densities calculated in the large cell (L = 460d). The open circles, squares and diamonds show the pressure calculated in cells of length L = 80d, 120d, 160d, respectively, demonstrating the convergence to the large-cell limit. The grey, dashed asymptotes schematically indicate the low temperature branch (left) and high temperature branch (right).

For this system the pressure curve P(v) is not an isotherm. The physical origin of its non-monotonic shape is completely different to that of a molecular fluid. The granular gas has no attraction between the particles; instead, the dilute phase is ‘heated’ more effectively due to its intimate coupling to the vibrating walls, while the dense phase is strongly cooled by its frequent dissipative inter-particle collisions23,31. As a result, the non-monotonic behaviour in our system can be regarded as a crossover from a low “temperature” branch at high densities (left dashed curve in Fig. 2) to a high “temperature” branch at low densities (right dashed curve in Fig. 2). The open symbols indicate the pressure calculated in cells of different size, showing the convergence to the large-cell limit. We see that the region between the two extrema of P(v) is unstable against phase separation, resulting in a pressure corresponding to two-phase coexistence, P* (horizontal dashed line).

Figure 3 shows P(v) as obtained from the small cell, juxtaposed with the pressure and volume per particle calculated using a long cell in which the system phase separates. Each circle represents an average over three driving cycles. Spatially the calculated pressure is approximately constant throughout the system, with a spatial mean value  . However, momentary imbalances in the energy injection and dissipation give rise to global pressure fluctuations around the temporal mean saturation pressure P*

. However, momentary imbalances in the energy injection and dissipation give rise to global pressure fluctuations around the temporal mean saturation pressure P*  . The corresponding densities fluctuate so as to remain on the pressure curve P(v), confirming that P(v) does indeed serve locally as the equation of state in both the liquid and gas phases.

. The corresponding densities fluctuate so as to remain on the pressure curve P(v), confirming that P(v) does indeed serve locally as the equation of state in both the liquid and gas phases.

The pressure-volume curve calculated using a simulation of the small cell and an expanded view close to P*.

The filled and open circles mark the averaged pressure and binodal volumes per particle for the liquid and gas phases respectively, obtained at different times. At each time, the average pressures in the two phases are equal to a good approximation.

It is interesting to note that the horizontal dashed line in Fig. 2, corresponding to P*, creates two approximately equal areas bounded above and below by the curve P(v) (hatched). Figure 4 shows the spinodal and binodal lines determined directly from phase separation in the large cell (filled symbols) and the predictions made by using the small cell (open symbols). The open circles indicate the binodal points obtained from P(v) by assuming a Maxwell equal-areas construction holds at the equal-areas pressure, Pe. The agreement is remarkable: in equilibrium thermodynamics the Maxwell construction is based on the minimization of the Gibbs free energy and as such is not expected to hold here. This finding was reproduced to a similar degree of accuracy for all levels of dissipation investigated, down to ε = 0.65.

Phase diagram for the liquid-gas-like phase separation.

The filled and open circles show the binodal points determined by the long cell simulations and those predicted by P(v) and the equal-areas construction, respectively. The triangles show the spinodal points determined from the onset of phase separation in the long cell simulations and those predicted by the unstable region of P(v), respectively.

Equal-areas construction

In search of a physical basis for the equal-areas rule, we discuss the fluctuations we have observed in the phase-separated system, depicted in Fig. 5. The fluctuations in the liquid fraction, fl (dotted), density of the liquid phase (dashed) and the mean pressure (solid) are strongly correlated because the volume and particle number are conserved and the system obeys an equation of state. Similar behaviour is observed in our experiments, which exhibit periodic fluctuations in the position of the interface.

When the pressure increases, the volume per particle decreases in each phase (as illustrated by Fig. 3) and both phases try to shrink. Since the total particle number and the volume of the cell are fixed, some particles in the liquid-like phase must be converted into the gas-like phase. There is a separation of time-scales between the frequency of pressure fluctuations (which are slow) and the frequency of collisions between particles (which are fast). We assume that the conversion of particles from one phase to the other occurs through a series of quasi-static states. As a consequence the mechanical work involved in such a change can be evaluated from a knowledge of P(v). At a pressure higher than Pe, the conversion of particles from liquid-like to gas-like requires mechanical work to be done on these particles. The converse is also true: if the pressure drops, the specific volumes grow and particles must be converted from the dilute to the dense phase. At a pressure lower than Pe this too requires mechanical work. We refer to the additional energy to exchange particles between phases at a pressure different from Pe as the residual mechanical work. Fluctuations of the pressure away from Pe in either direction require residual mechanical work. In contrast to the quasi-static pressure variation, the granular temperature has fast dynamics; its value is governed by the evolution of the slow variables alone21.

Taken all together these observations suggest the following purely mechanical model which uniquely identifies the saturation pressure and the binodal densities. Let the total volumes of the phases be Vi = Nivi, where Ni and vi are the number of particles and the specific volumes, respectively, for i ∈ {l, g}. For any fluctuation, the total number and volume of the particles is fixed and vl and vg change so that  , the instantaneous pressure. For our granular gas we have shown that the pressure oscillates and define

, the instantaneous pressure. For our granular gas we have shown that the pressure oscillates and define  . The corresponding change in the specific volume is defined to be

. The corresponding change in the specific volume is defined to be  , where

, where  are the specific volumes at the equal-areas pressure. It is straightforward to determine

are the specific volumes at the equal-areas pressure. It is straightforward to determine  directly from the equation of state. The difference between the left and right shaded areas in Fig. 6 illustrates the average amount of work required to convert one particle from the dense to the dilute phase at a mean pressure

directly from the equation of state. The difference between the left and right shaded areas in Fig. 6 illustrates the average amount of work required to convert one particle from the dense to the dilute phase at a mean pressure  . Only if Pe is the equal-areas pressure is this difference equal to the hatched area and given by

. Only if Pe is the equal-areas pressure is this difference equal to the hatched area and given by

where  and

and  .

.

For the system to obey the equation of state, P(v),  . In any fluctuation

. In any fluctuation  and

and  , so that

, so that

where the primes indicate derivatives with respect to  and the

and the  s are minus the compressibilities in each of the two phases. By defining

s are minus the compressibilities in each of the two phases. By defining  we can rewrite this as

we can rewrite this as

Therefore the total residual mechanical work done for a finite fluctuation,  , is given by

, is given by

which to leading order reduces to

as  and

and  are both negative. Since

are both negative. Since  is quadratic in

is quadratic in  any fluctuation that shifts the pressure away from Pe while keeping the volumes per particle on P(v) requires residual mechanical work to be done. We hypothesise that, because of dissipation, the system tries to minimise the residual mechanical work and

any fluctuation that shifts the pressure away from Pe while keeping the volumes per particle on P(v) requires residual mechanical work to be done. We hypothesise that, because of dissipation, the system tries to minimise the residual mechanical work and  fluctuates around Pe as observed in simulations.

fluctuates around Pe as observed in simulations.

It is interesting to quote from Maxwell’s discussion of the equal-areas rule in equilibrium systems: “Since the temperature has been constant throughout, no heat has been transformed into work”32. In our system the temperature is not constant throughout an expansion, yet, because the system tries to remain on the equation of state, an equal-areas rule still appears to be applicable to a good approximation. It is based solely on the minimization of the residual mechanical work.

The equal-area construction described above is able to predict the coexisting pressure remarkably well, typically to within less than 2%. However, it is not exact. In Fig. 7 we show the pressure deviation Pdev = (Pe − P*)/Pe as a function of amplitude. As the amplitude increases, the deviation decreases and approaches zero at the critical point, A = 3.2 d, as would be expected. We attribute the deviation from the equal-areas construction to the shape of  and to the fluctuations observed in experiment and simulation. If

and to the fluctuations observed in experiment and simulation. If  were a symmetric function, the mean pressure P* would be expected to be equal to the minimum of W, namely Pe. However, in general

were a symmetric function, the mean pressure P* would be expected to be equal to the minimum of W, namely Pe. However, in general  is not symmetric and the mean pressure is not equal the pressure at the minimum.

is not symmetric and the mean pressure is not equal the pressure at the minimum.

To quantify the asymmetry, we model the curvature of P(v) close to the Maxwell points as  . By substituting for Gi in Eq. 1 and Eq. 3 and expanding Eq. 4 as a power series in

. By substituting for Gi in Eq. 1 and Eq. 3 and expanding Eq. 4 as a power series in  , we find that the

, we find that the  term vanishes when

term vanishes when

Details of the calculation are given in the supplemental material. Since  ,

,  and

and  , the nonlinearity should vanish when

, the nonlinearity should vanish when  . The crosses in Fig. 7 show C calculated from small-cell simulations for different driving amplitudes. Both Pdev and C extrapolate to zero at the critical point and increase in magnitude as the driving amplitude decreases, indicating that deviations from the Maxwell construction are caused by an increase in the nonlinearity.

. The crosses in Fig. 7 show C calculated from small-cell simulations for different driving amplitudes. Both Pdev and C extrapolate to zero at the critical point and increase in magnitude as the driving amplitude decreases, indicating that deviations from the Maxwell construction are caused by an increase in the nonlinearity.

Discussion

So far we might conclude that the minimization of residual mechanical work, as outlined above, holds generally, which would suggest that an analogue of a free energy functional could be obtained for our system, e.g., by integration of P(v). This would be in line with conclusions drawn previously from results obtained much closer to the elastic limit21. However, this is not the complete picture.

One has to appreciate that the Maxwell construction is only an approximation, based on the assumption that the slow, mechanical variables (the pressure and the density), are completely decoupled from the fast kinetic variables (the temperature, dissipation and energy injection from the walls). As such any free energy analogue derived from P(v) will be predictive only for the mechanical variables. Conversely, the minimisation principle that we have obtained will not be useful to describe nor predict any aspects of the kinetic variables. Since it is the kinetic variables which give rise to the non-monotonic pressure characteristic23, the free-energy analogue cannot describe the NESS in its entirety.

Finally, we note that a number of studies on shear flow of granules have observed a non-monotonic dependence of the pressure on the volume. Campbell33 and later Alam & Luding34 showed that the stress tensor dependence on the solid fraction has a characteristic U-shape with asymptotes at both the low density limit and at the density of the shearable limit (random-close packing). We remark that the physical origin of the non-monotonicity is, however, different. In simulations of shear flow33,34 the stresses diverge at low density because the few collisions taking place at low density must dissipate increasingly large amounts of energy; at high density the stresses grow because they reach the limit where considerable stresses are necessary to initiate or maintain the shear flow35. The different natures of the contributions to the stress tensor at low and high filling fractions are reflected in the separation of the stress tensor in streaming and collisional contributions, which bring about the low and the high filling fraction divergences, respectively. Conversely, the steady state in our results arises from a balance of different rates of dissipation in the liquid-like and gas-like phases. The crossover from the low temperature, dense phase to the high temperature, dilute phase in the presence of an interface between them engenders the non-monotonic behaviour of P(v) in Fig. 2. Furthermore, the kinetic theories of Jenkins & Savage36 and Lun et al.37, e.g., are based on the assumption that fluctuations (that is, gradients in the density, temperature and velocity) are small. This assumption is strongly violated in our conditions (see Fig. 5). The determination of the equation of state for strongly driven systems is then called for.

It would nevertheless be interesting to compare our results with the framework provided by the kinetic theory of granular systems36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. The interplay of the dynamical fluctuations with the boundary driving, which generates the results presented here, should prove an important testing bed for generalizations of the kinetic theory. This is left for future work.

Methods

Experiments

Our experimental apparatus is very similar to that used previously23. Glass particles were confined between parallel horizontal plates in a long, thin cell. The particles were sieved and selected under a microscope to obtain a sample of approximately monodisperse spheres with diameter d = 610 μm. The cell was constructed from a lower plate of 3 mm thick, anodized aluminum and a top plate of 3 mm thick glass. The plates were separated by 10 mm high aluminum walls which also confined the particles horizontally such that the internal length, width and height of the cell were 280 mm, 10 mm and 10 mm, respectively. The cell was driven sinusoidally in the vertical direction, with variable amplitude, A. The driving frequency was kept fixed at 60 Hz. The mean density is defined as  , where N is the number of particles, vp is the volume of a single particle and V is the internal volume of the cell. Care was taken to ensure that the cell was level prior to each experimental run.

, where N is the number of particles, vp is the volume of a single particle and V is the internal volume of the cell. Care was taken to ensure that the cell was level prior to each experimental run.

Computer simulations

In addition to our experiments, we have also carried out time-driven molecular dynamics simulations. The simulations have previously been shown to accurately capture the physics of the system under study19,23. The particles are modelled as monodisperse soft-spheres with diameter d = 610 μm. Dissipation is included by a normal coefficient of restitution, ε (implemented using a linear-spring and dash-pot damping)45. The effects of tangential forces and rotational degrees of freedom are neglected because these have been shown to have minor impact on the physics of the system46,47,48. The simulated cell has dimensions 460d × 20d × 16.4d, thus closely resembling the experimental system. Reflecting boundary conditions on the short walls of the cell are used in order to study a single interface between two coexisting phases. On the long walls, periodic boundary conditions are employed. The results presented in this paper are for ε = 0.8, matching well with the experiment, but similar results are found for the rather wide range of  , that is, all coefficients of restitution for which the liquid-gas phase separation can be uniquely identified.

, that is, all coefficients of restitution for which the liquid-gas phase separation can be uniquely identified.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Clewett, J. P. D. et al. The minimization of mechanical work in vibrated granular matter. Sci. Rep. 6, 28726; doi: 10.1038/srep28726 (2016).

References

Meron, E. Pattern-formation approach to modelling spatially extended ecosystems. Ecol. Model. 234, 70–82 (2012).

Sato, D. et al. Synchronization of chaotic early afterdepolarizations in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2983–2988 (2009).

Marchetti, M. C. et al. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1143–1189 (2013).

Yuan, J., Wang, J., Xu, Z. & Li, B. Time-dependent collective behavior in a computer network model. Physica A 368, 294–304 (2006).

Foster, J. Energy, aesthetics and knowledge in complex economic systems. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 80, 88–100 (2011).

Gollub, J. P. & Langer, J. S. Pattern formation in nonequilibrium physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, S396–S403 (1999).

Aranson, I. S. & Tsimring, L. S. Patterns and collective behavior in granular media: Theoretical concepts. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 641–692 (2006).

De Groot, S. R. & Mazur, P. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics (Dover Publications, 2013).

Jaeger, H. M. & Liu, A. J. Far-from-equilibrium physics: An overview. arXiv 1009.4874 (2010).

Egolf, D. A. Equilibrium regained: From nonequilibrium chaos to statistical mechanics. Science 287, 101–104 (2000).

Seifert, U. Stochastic thermodynamics, fluctuation theorems and molecular machines. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 126001 (2012).

Joubaud, S., Lohse, D. & van der Meer, D. Fluctuation theorems for an asymmetric rotor in a granular gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 210604 (2012).

Jaeger, H. M., Nagel, S. R. & Behringer, R. P. Granular solids, liquids and gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 1259–1273 (1996).

Visco, P., Puglisi, A., Barrat, A., Trizac, E. & van Wijland, F. Fluctuations of power injection in randomly driven granular gases. J. Stat. Phys. 125, 533–568 (2006).

Shattuck, M. D., Ingale, R. A. & Reis, P. M. Granular thermodynamics. AIP Conf. Proc. 1145, 43–50 (2009).

Brilliantov, N. V. & Pöschel, T. Kinetic Theory of Granular Gases (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Prevost, A., Melby, P., Egolf, D. A. & Urbach, J. S. Nonequilibrium two-phase coexistence in a confined granular layer. Phys. Rev. E 70, 050301 (2004).

Clerc, M. et al. Liquid-solid-like transition in quasi-one-dimensional driven granular media. Nature Physics 4, 249–254 (2008).

Clewett, J. P. D., Roeller, K., Bowley, R. M., Herminghaus, S. & Swift, M. R. Emergent surface tension in vibrated, noncohesive granular media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 228002 (2012).

Argentina, M., Clerc, M. G. & Soto, R. van der Waals-like transition in fluidized granular matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 044301 (2002).

Soto, R., Argentina, M. & Clerc, M. Van der Waals-like transition in fluidized granular matter. In Pöschel, T. & Brilliantov, N. (eds.) Granular Gas Dynamics, vol. 624 of Lecture Notes in Physics 317–333 (Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2003).

Liu, R., Li, Y., Hou, M. & Meerson, B. van der Waals-like phase-separation instability of a driven granular gas in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. E 75, 061304 (2007).

Roeller, K., Clewett, J. P. D., Bowley, R. M., Herminghaus, S. & Swift, M. R. Liquid-gas phase separation in confined vibrated dry granular matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 048002 (2011).

Khain, E., Meerson, B. & Sasorov, P. V. Phase diagram of van der Waals-like phase separation in a driven granular gas. Phys. Rev. E 70, 051310 (2004).

Allen, M. P. & Tildesley, D. J. Computer simulation of liquids (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1987).

Livne, E., Meerson, B. & Sasorov, P. Symmetry-breaking instability and strongly peaked periodic clustering states in a driven granular gas. Phys. Rev. E 65, 021302 (2002).

Khain, E. & Meerson, B. Symmetry-breaking instability in a prototypical driven granular gas. Phys. Rev. E 66, 021306 (2002).

Cartes, C., Clerc, M. & Soto, R. van der Waals normal form for a one-dimensional hydrodynamic model. Phys. Rev. E 70, 031302 (2004).

Takahashi, H., Nakamura, A. & Nitta, T. Effect of the shape of simulation box on the van der Waals loop of a Lennard-Jones fluid. Chem. Phys. Lett. 282, 128–132 (1998).

Binder, K., Block, B. J., Virnau, P. & Tröster, A. Beyond the van der Waals loop: What can be learned from simulating Lennard-Jones fluids inside the region of phase coexistence. Am. J. Phys. 80, 1099–1109 (2012).

Herminghaus, S. Wet Granular Matter: A Truly Complex Fluid (Series in Soft Condensed Matter) (World Scientific Publishing, 2013).

Maxwell, J. C. On the dynamical evidence of the molecular constitution of bodies. Nature 11, 374 (1875).

Campbell, C. S. The stress tensor for simple shear flows of a granular material. J. Fluid Mech. 203, 449–473 (1989).

Alam, M. & Luding, S. Rheology of bidisperse granular mixtures via event-driven simulations. J. Fluid Mech. 476, 69–103 (2003).

Campbell, C. S. Granular material flows-an overview. Powder Technol. 162, 208–229 (2006).

Jenkins, J. T. & Savage, S. B. A theory for the rapid flow of identical, smooth, nearly elastic, spherical particles. J. Fluid Mech. 130, 187–202 (1983).

Lun, C. K. K., Savage, S. B., Jeffrey, D. J. & Chepurniy, N. Kinetic theories for granular flow: inelastic particles in couette flow and slightly inelastic particles in a general flowfield. J. Fluid Mech. 140, 223–256 (1984).

Johnson, P. C. & Jackson, R. Frictional-collisional constitutive relations for granular materials, with application to plane shearing. J. Fluid Mech. 176, 67–93 (1987).

Lun, C. K. K. Kinetic theory for granular flow of dense, slightly inelastic, slightly rough spheres. J. Fluid Mech. 233, 539–559 (1991).

Garzó, V. & Dufty, J. W. Dense fluid transport for inelastic hard spheres. Phys. Rev. E 59, 5895 (1999).

Goldhirsch, I. Rapid granular flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 35, 267–293 (2003).

Luding, S. Towards dense, realistic granular media in 2d. Nonlinearity 22, R101 (2009).

Berzi, D. Extended kinetic theory applied to dense, granular, simple shear flows. Acta Mech. 225, 2191–2198 (2014).

Vescovi, D., Berzi, D., Richard, P. & Brodu, N. Plane shear flows of frictionless spheres: Kinetic theory and 3d soft-sphere discrete element method simulations. Phys. Fluids 26, 053305 (2014).

Schwager, T. & Pöschel, T. Coefficient of restitution and linear-dashpot model revisited. Granular Matter 9, 465–469 (2007).

Luding, S. Granular materials under vibration: Simulations of rotating spheres. Phys. Rev. E 52, 4442–4457 (1995).

Paolotti, D., Cattuto, C., Marini Bettolo Marconi, U. & Puglisi, A. Dynamical properties of vibrfluidized granular mixtures. Granul. Matter 5, 75–83 (2003).

Nichol, K. & Daniels, K. E. Equipartition of rotational and translational energy in a dense granular gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 018001 (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.D.C., M.R.S. and M.G.M. conceived and designed the work; J.P.D.C. and J.W. carried out the simulations; J.P.D.C. performed the experiments; J.P.D.C., R.M.B., S.H., M.R.S. and M.G.M. wrote the paper. All the authors commented on and revised the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Clewett, J., Wade, J., Bowley, R. et al. The minimization of mechanical work in vibrated granular matter. Sci Rep 6, 28726 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28726

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28726

This article is cited by

-

Geometry-controlled phase transition in vibrated granular media

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

, smoothed by a Gaussian filter over three driving cycles.

, smoothed by a Gaussian filter over three driving cycles.

.

.

.

.