Abstract

Luminescent materials with dynamic photoluminescence activity have aroused special interest because of their potential widespread applications. One proposed approach of directly and reversibly modulating the photoluminescence emissions is by means of introducing an external electric field in an in-situ and real-time way, which has only been focused on thin films. In this work, we demonstrate that real-time electric field-induced photoluminescence modulation can be realized in a bulk Ba0.85Ca0.15Ti0.90Zr0.10O3 ferroelectric ceramic doped with 0.2 mol% Pr3+, owing to its remarkable polarization reversal and phase evolution near the morphotropic phase boundary. Along with in-situ X-ray diffraction analysis, our results reveal that an applied electric field induces not only typical polarization switching and minor crystal deformation, but also tetragonal-to-rhombohedral phase transformation of the ceramic. The electric field-induced phase transformation is irreversible and engenders dominant effect on photoluminescence emissions as a result of an increase in structural symmetry. After it is completed in a few cycles of electric field, the photoluminescence emissions become governed mainly by the polarization switching and thus vary reversibly with the modulating electric field. Our results open a promising avenue towards the realization of bulk ceramic-based tunable photoluminescence activity with high repeatability, flexible controllability and environmental-friendly chemical process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapid and reversible manipulations of photoluminescence (PL) activity in luminescent materials have attracted much attention due to wide applications, including long-distance quantum communication, photonic devices, volumetric 3D display, back light and biomedicine1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Until now, the modulation of PL is commonly achieved by adjusting the composition of host materials and/or doping various rare-earth ions (RE3+) via chemical approach in phosphor5,8,9,10. However, these approaches are irreversible and not favorable for practical applications. They also provide no opportunities to elaborate the mutative PL process, which is essential for exploring the underlying physical mechanism. In this regard, an in-situ and real-time approach for PL modulation has been proposed by applying an external electric field on specific host materials such as organic thin films11,12 and ferroelectric titanate films2,13,14. As known, ferroelectrics are materials that have spontaneous electric polarization (or electric dipoles) that can be reversed by the application of an external electric field.

An important assumption underlying much of the electric field modulation work is that the reversible variation of PL should be attributed to electrically changing the structural symmetry of the host and thus tailoring the local crystal field around the RE3+ 15,16,17. Low-symmetry hosts typically exert a crystal field containing more uneven components around the dopant ions compared with high-symmetry counterparts16,18. The uneven components enhance the electronic coupling between 4f energy levels and higher 4f5d configuration and subsequently increase f–f transition probabilities of the dopant ions19. The common approaches for ferroelectric hosts to rationally tune structural symmetry are based on those coupling physical factors that can respond well to external electric field such as biaxial strain14,20, polarization2,21,22,23, or phase transition24,25.

Despite a significant modulation of PL by applying external electric field has been realized in a reversible and in-situ manner, this achievement is only reported for ferroelectric thin films2,13,14. It is known that bulk ceramics offer several advantages compared with thin films, including higher repeatability, much better chemically inert and thermal stability, superior mechanical properties, easier preparation process and lower cost to meet the market requirements. Among the environmental-friendly ferroelectric ceramics, Ba0.85Ca0.15Ti0.90Zr0.10O3 (abbreviated as BCTZ) possesses excellent piezoelectricity owing to its composition proximity of the morphotropic phase boundary (MPB) to a tri-critical triple point26. Inspired by its remarkable polarization reversal and phase revolution around room temperature, BCTZ is chosen as the ferroelectric host in this work for providing a considerable change in structural symmetry under electric field. In addition, these features also provide the ceramic a highly reliable response to electric field change and allow the use of a low voltage for inducing the structural change.

Meanwhile, Pr-doped luminescent materials have shown great potential in applications, such as red phosphor for the display applications27,28, sensors and optical-and-electro multifunctional integration29,30,31. Unlike other RE3+, Pr3+ has a unique characteristic. Namely, resulting from the close energy separation between the 1S0 level and the lowest edge of the 4f5d configuration, its emission depends strongly on the position of the 4f5d configuration, which is extremely influenced by the characteristics of the host32,33,34. For instance, the PL performances of Pr-doped ferroelectric ceramics can be enhanced greatly by electric field, as a result of the lowering of structural symmetry in the host after poling22,35. Owing to the high sensitivity, the emissions of Pr3+ have also been utilized as a structural transition probe for investigating phase transition of ferroelectric hosts that induces crystal-symmetry changes36,37,38. On the other hand, the ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties of the host materials can also be improved by the doping of Pr29,39.

In this work, we report the real-time PL modulation in bulk Ba0.85Ca0.15Ti0.90Zr0.10O3 ferroelectric ceramic doped with 0.2 mol% Pr3+ (abbreviated as BCTZ:Pr). To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on direct PL in-situ modulation of bulk ceramics showing a reversible manner by applying external electric field. For BCTZ, its structural transition between tetragonal and rhombohedral phases as well as the dipole switching is considerably susceptible of electric field due to the MPB effect. Accordingly, we aim to modify the structural symmetry of the BCTZ host with a dynamic electric field, thus tailoring the local crystal field around Pr3+. Figure 1 shows the schematic of a sandwiched structure used for continuously detecting the down-shifting PL emissions of BCTZ:Pr. A silver electrode (~10 μm) was first coated on the back surface of a thin ceramic disk with a thickness of ~200 μm and then a conductively transparent electrode of indium tin oxide (ITO) (~0.4 μm) was deposited on the top surface at 250 °C by magnetron sputtering. The transparent ITO enables the excitation and emission light to pass through under an external electric field applied along the thickness direction (Fig. 1a). With switching on the external electric field, changes in PL are induced via modulating phase transition and polarization switching (Fig. 1b,c) by virtue of the extremely high sensitivity of the local crystal field around Pr3+ to external electric field2,20.

Results and Discussion

In-situ Structure and Phase Transition

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the BCTZ:Pr ceramic is shown in Fig. 2a, revealing a pure perovskite structure of the ceramic. No additional peaks reflecting the presence of rare-earth oxides are observed, which suggests that the Pr3+ have diffused into the BCTZ lattice. The standard diffraction peaks are cited from the tetragonal (T) BaTiO3 (PDF#05-0626) and rhombohedral (R) BaTiO3 (PDF#85-0368), indicated by the vertical lines for comparison (Fig. 2a). Regarding the fact that the BCTZ ceramic derives from MPB with the coexistence of tetragonal (P4mm) and rhombohedral phases (R3m) around room temperature26,40, there is no visible evidence of the splitting of (200) peak at 2θ~45° (Fig. 2a). A broad diffraction peak is observed around 44°–46° as shown in Fig. 2b. It should be noted that the enlarged XRD pattern shown in Fig. 2b was obtained by fine X-ray scanning on the ceramic ready for applying an in-situ electric field, i.e., with both Ag and ITO electrodes. Owing to the complexity (coexistence of phases) and interference arisen from the strong diffraction peaks of ITO, the Rietveld refinement method has not been used for precisely identifying the crystal structure. Instead, with the primary aim of verifying the change of crystal structure, the broad diffraction peak has been resolved by the practical peak fitting method25, giving the fitting results indicated in Fig. 2b. For the ceramic without an electric field (E = 0), it is characterized by the obvious (200)T and (200)R peaks, which indicates that the coexistence of tetragonal and rhombohedral phases (even including an intermediate orthorhombic sub-phase (002)) at room temperature40. Under an electric field of 0.2 kV/mm, the (200)T peak shrinks and becomes similar in size to the (200)R peak (Fig. 2b). As the in-situ electric field increases to 0.8 kV/mm, the tetragonal (200)T peak almost disappears whereas the (200)R peak grows to the dominant one. Finally, the diffraction peak becomes relatively narrow with an evident (200)R peak under an electric field of 2 kV/mm, revealing a transformation from a mainly tetragonal phase into a mainly rhombohedral phase. This unique ferroelectric phase evolution corresponds to the symmetry-raising characteristic and agrees well with previous literature21 and the established ferroelectric phase diagram26. Although the (002) peak cited by the orthorhombic phase may exist in the ceramic, we regard it as an instable intermediate phase induced by E-field dependent phase evolution41,42.

For studying the reversibility of the phase transformation, the electric field has been switched off and on between 0 and 2 kV/mm for a number of times and the XRD patterns in-situ with the off- and on-fields for another as-prepared sample have been measured, giving the results shown in Fig. 2c. The transformation under the first off- and on-fields has been discussed above and the XRD patterns are similar to those shown in Fig. 2b. As shown in Fig. 2c, the diffraction peak becomes broadened again when the field is switched off (i.e., 2nd). However, the peak does not restore to the original shape (i.e., 1st), in particular for the (200)T peak, suggesting that the tetragonal phase cannot be completely recovered. Furthermore, the (200)T peak is even hardly observed in the subsequent switching processes (i.e., 3rd). Instead, only the (200)R peaks is clearly observed at the same diffraction angle 2θ~44.9° under both the on- and off-fields. These suggest that the field-induced ferroelectric phase transition takes place indeed but is not completely reversible. It takes at least three cycles of electric field to completely irreversibly transform the phase from tetragonal to rhombohedral, which then becomes unaffected by the electric field.

Electrical Properties

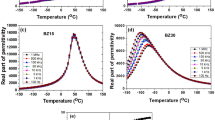

The temperature dependences of dielectric constant (εr) and dielectric loss factor (tanδ) at 10 kHz for the un-poled and poled BCTZ:Pr ceramics are shown in Fig. 3a. For the un-poled sample, a strong peak corresponding to the tetragonal-cubic phase transition (TC~85 °C) is clearly observed in the temperature range of 25–150 °C. As evidenced by the variation of tanδ, a very weak peak assigned to the rhombohedral–tetragonal phase transition (TR-T) is barely observed around 40 °C. After poling under a dc electric field of 2 kV/mm, the weak transition peak (in εr) becomes stronger and can easily be observed at similar TR-T. This should be arisen from the increase in rhombohedral phase and thus provides evidences for the irreversible ferroelectric phase evolution induced by the poling field at room temperature (Fig. 2c). Figure 3b plots the ferroelectric hysteresis loop (P-E loop) of the BCTZ:Pr ceramic. As seen, it displays a typically saturated shape and the remanent polarization Pr and coercive field Ec are about 11.8 μC/cm2 and 0.21 kV/mm, respectively. In addition, the ceramic also exhibits good electrical properties, such as a high piezoelectric coefficient d33 (~410 pC/N), large electromechanical coupling factor kp (~50.6%), high εr (~3620) and low tanδ (~1.6%).

Photoluminescence Excitation and Emission

The photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectrum monitoring the typical red emission of Pr3+ (650 nm) of the BCTZ:Pr ceramic is shown in Fig. 4. Three strong excitation peaks arising from the excitations of Pr3+ from the 3H4 ground level to the 3P2, 3P1 and 3P0 excited levels are observed at 450, 473 and 487 nm, respectively18,39. Accordingly, the photoluminescence (PL) emission spectrum of the ceramic has been measured under an excitation of 450 nm, giving the results shown in Fig. 4. Similar to other Pr-doped luminescent materials23,34, the ceramic exhibits strong red (650, 617, 602 nm) and weak green (547, 529 nm) emissions, which are attributed to the transitions (3P0 → 3F2, 3P0 → 3H6, 1D2 → 3H4) and (3P0 → 3H5, 3P1 → 3H5), respectively. Probably due to the slight differences in compositions which could influence the cross-relaxation process of Pr3+ 43, the strongest red emission occurs at 650 nm (Fig. 4), instead of 600 nm reported for the (Ba0.85Ca0.15)1-xPrx(Zr0.1Ti0.9)O3 ceramics21. Owing to its strong intensity and f-f transition characteristics, the emission at 650 nm has been selected for studying the dynamic PL emissions under external electric field.

In-situ PL Modification

Figure 5 shows the dynamic PL responses of the BCTZ:Pr ceramic under a biased ac electric field E which varies sinusoidally between 0 and 2 kV/mm. It is of great interest to notice that the observed PL intensity varies in a similar manner of E, suggesting that the PL emissions could be modulated reversibly, to some extent, by an external electric field. Indeed, different mechanisms may be involved in modulating the PL emissions, in particular for the first half cycle of E. As shown in Fig. 5, the observed PL decreases first slowly as E increases and then falls rapidly at E > 0.5 kV/mm. The dramatic PL quenching (~22%) at high E should be attributed to the field-induced phase transformation as evidenced by the in-situ XRD analysis illustrated in Fig. 2. It has been known that the PL emissions are affected by the local crystal field around RE3+ and thus the structural symmetry of the host in accordance to the Judd-Ofelt (J-O) theory44,45; namely, a high structural symmetry will lead to a weak PL emission. For the BCTZ:Pr ceramic, it possesses a mainly tetragonal phase and then lower structural symmetry at low electric fields (Fig. 2b). As E increases to 2 kV/mm, it undergoes a transformation to a mainly rhombohedral phase and thus engendering an increase in structural symmetry, which consequently leads to a decrease in PL intensity. As E decreases from 2 kV/mm to zero (i.e., the other half cycle of E), the observed PL intensity increases but cannot restore to the original value. There is a drop of 18% in PL intensity after the first cycle of E. This should also be attributed to the field-induced phase transformation which has been shown only partially reversible46. As evidenced in Fig. 2c, the ceramic contains more rhombohedral phase after the first cycle of E and hence possesses higher structural symmetry and exhibits weaker PL emissions.

It should be noted that polarization switching also occurs in the first half cycle of E, which, however, enhances PL emissions as a result of the lowering of structural symmetry and the resulting increase in uneven components of the local crystal field around Pr3+. The uneven crystal field can mix opposite-parity states into the 4f configuration level and then increase the 4f-4f electric dipole transition probability of Pr3+ 16,18. Apparently, the polarization switching and phase transformation have opposite effects on PL emissions, and, on the basis of the results (Fig. 5), the effect of the latter is dominant. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, most of the ferroelectric dipoles are switched for alignment by an electric field smaller than 0.6 kV/mm, suggesting the resulting enhancement in PL emissions should become saturated at similar electric field. Probably due to the limited counter-effect, the observed PL intensity (which is modulated mainly by phase transformation) starts to decrease rapidly at E~0.5 kV/mm as shown in Fig. 5. Also, as illustrated in Fig. 3b, part of the aligned ferroelectric dipoles (about 40%) will relax as the electric field decreases from 2 kV/mm to 0, which consequently increases the structural symmetry and then weakens the PL emissions.

As evidenced in Fig. 2c, it takes at least three cycles of electric field to complete the irreversible tetragonal-to-rhombohedral transformation. Consequently, the effect of phase transformation on PL emissions decreases continuously in the 2nd and 3rd cycles of E and becomes vanished in the subsequent cycles. The observed PL intensity is then modulated mainly by polarization switching and thus starts to increase, instead of decrease, as E increase from 0 in each subsequent cycle of E, in particular for the 4th to 10th cycles as shown in Fig. 6. Although no phase transformation is induced, the applied electric field may induce local crystal strain and thus deforming the rhombohedral structure slightly as indicated by the XRD results shown in the insets of Fig. 6. The change is reversible and leads to an increase in structural symmetry14,47 and then a decrease in PL intensity. However, it is very weak as compared with that arisen from polarization switching which increases the PL emission as discussed above. As a result, the observed PL intensity follows mainly the variation of E, but starts to decrease before E reaching its amplitude in each cycle (Fig. 6).

Conclusion

In summary, we report a real-time modulation of down-shifting PL emissions of the BCTZ:Pr bulk ceramic via the application of an external electric field. The remarkable polarization reversal and phase evolution of BCTZ:Pr deriving from a tri-critical point near MPB enable reliable responses to the applied electric field. As evidenced by in-situ X-ray diffraction analysis, the applied electric field induces not only typical polarization switching and minor crystal deformation, but also tetragonal-to-rhombohedral phase transformation of the host. Unlike the former two responses, the field-induced phase transformation is irreversible, but engenders greater effect on PL emissions as a result of an increase in structural symmetry. After the phase transition is completed in a few cycles of electric field, the PL emissions become governed mainly by the reversible polarization switching. Owing to the minor and opposite effect arisen from the field-induced local crystal strain, the observed PL intensity however deviates slightly from the modulating electric field. Herein, this work could pave the way for PL modulation of bulk ceramic-based device applications, such as further electric controlled photoluminescence down-convertors.

Methods

Samples

The raw materials used to fabricate the Ba0.85Ca0.15Ti0.90Zr0.10O3 ceramics with 0.2 mol% Pr doping were commercially available carbonate powders and metal oxides: BaCO3 (99.5%), CaCO3 (99%), TiO2 (99.9%), ZrO2 (99.9%) and Pr6O11 (99.9%). The powders in the stoichiometric ratio were ball-milled thoroughly in anhydrous ethanol using zirconia balls for 12 h, then calcined at 1200 °C for 2 h in air before ball-milled again for 12 h and sieved through an 80-mesh screen. After mixed thoroughly with a PVA binder solution, the resulting mixture was pressed into disk samples. Then, the samples were finally sintered at 1350 °C for 2 h in air for densification. The ceramics were poled under an electric field of 2 kV/mm at room temperature in silicone oil for 30 min. Before the measurements of in-situ XRD and PL properties, a silver electrode was first fired on one of the surfaces while an indium tin oxide (ITO) transparent electrode was deposited on the other surface by sputtering technique.

Measurements

The crystallite structure was examined using XRD analysis with CuKα radiation (SmartLab, Rigaku Co., Japan). ɛr and tan δ were measured as functions of temperature using an impedance analyzer (HP 4194A, Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA). A conventional Sawyer-Tower circuit was used to measure the P-E loop at 10 Hz. The piezoelectric coefficient (d33) was measured using a piezo-d33 meter (ZJ-3A, China).

The DC PLE and PL visible emission spectra were measured by a spectrophotometer (FLSP920, Edinburgh Instruments, UK) using a 450-nm xenon arc lamp (Xe900) as the excitation source. A voltage source (2410 1100V Source meter, Keithley Instruments Inc., US) was used to apply external voltage for investigating the E-field dependent XRD and PL properties.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Sun, H. L. et al. In-situ Electric Field-Induced Modulation of Photoluminescence in Pr-doped Ba0.85Ca0.15Ti0.90Zr0.10O3 Lead-Free Ceramics. Sci. Rep. 6, 28677; doi: 10.1038/srep28677 (2016).

References

De Greve, K. et al. Quantum-dot spin-photon entanglement via frequency downconversion to telecom wavelength. Nature 491, 421–425, 10.1038/nature11577 (2012).

Hao, J., Zhang, Y. & Wei, X. Electric-Induced Enhancement and Modulation of Upconversion Photoluminescence in Epitaxial BaTiO3:Yb/Er Thin Films. Angew. Chem. 123, 7008–7012, 10.1002/ange.201101374 (2011).

Cohen, B. E. Biological imaging: Beyond fluorescence. Nature 467, 407–408 (2010).

Wang, F. et al. Simultaneous phase and size control of upconversion nanocrystals through lanthanide doping. Nature 463, 1061–1065, 10.1038/nature08777 (2010).

Yang, J. et al. Controllable red, green, blue (RGB) and bright white upconversion luminescence of Lu2O3:Yb3+/Er3+/Tm3+ nanocrystals through single laser excitation at 980 nm. Chemistry 15, 4649–4655, 10.1002/chem.200802106 (2009).

Bai, G., Tsang, M. K. & Hao, J. Tuning the luminescence of phosphors: beyond conventional chemical method. Adv. Opt. Mater. 3, 431–462 (2015).

Wang, H.-Q., Batentschuk, M., Osvet, A., Pinna, L. & Brabec, C. J. Rare-Earth Ion Doped Up-Conversion Materials for Photovoltaic Applications. Adv. Mater. 23, 2675–2680, 10.1002/adma.201100511 (2011).

Zhou, G. et al. Manipulating Charge-Transfer Character with Electron-Withdrawing Main-Group Moieties for the Color Tuning of Iridium Electrophosphors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 499–511, 10.1002/adfm.200700719 (2008).

Lai, S.-L. et al. High Efficiency White Organic Light-Emitting Devices Incorporating Yellow Phosphorescent Platinum(II) Complex and Composite Blue Host. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 5168–5176, 10.1002/adfm.201300281 (2013).

Heer, S., Lehmann, O., Haase, M. & Gudel, H. U. Blue, green and red upconversion emission from lanthanide-doped LuPO4 and YbPO4 nanocrystals in a transparent colloidal solution. Angew. Chem. 42, 3179–3182, 10.1002/anie.200351091 (2003).

Adams, D. M., Kerimo, J., Liu, C.-Y., Bard, A. J. & Barbara, P. F. Electric field modulated near-field photo-luminescence of organic thin films. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 6728–6736 (2000).

McNeill, J. D., O’Connor, D. B., Adams, D. M., Barbara, P. F. & Kämmer, S. B. Field-induced photoluminescence modulation of MEH-PPV under near-field optical excitation. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 76–82 (2001).

Bai, G., Zhang, Y. & Hao, J. Tuning of near-infrared luminescence of SrTiO3: Ni2+ thin films grown on piezoelectric PMN-PT via strain engineering. Sci. Rep. 4 (2014).

Wu, Z. et al. Effect of biaxial strain induced by piezoelectric PMN-PT on the upconversion photoluminescence of BaTiO3:Yb/Er thin films. Opt. Express 22, 29014–29019, 10.1364/OE.22.029014 (2014).

Blasse, G. & Grabmaier, B. [A General Introduction to Luminescent Materials] Luminescent materials [1–9] (Springer, Berlin, 1994).

Wang, F. & Liu, X. Recent advances in the chemistry of lanthanide-doped upconversion nanocrystals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 976–989, 10.1039/b809132n (2009).

Mahata, M. K. et al. Incorporation of Zn2+ ions into BaTiO3: Er3+/Yb3+ nanophosphor: an effective way to enhance upconversion, defect luminescence and temperature sensing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 20741–20753 (2015).

Wu, X., Lau, C. M., Kwok, K. W. & Xie, R. J. Photoluminescence Properties of Er/Pr-Doped K0.5Na0.5NbO3Ferroelectric Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 98, 2139–2145, 10.1111/jace.13605 (2015).

Blasse, G. & Grabmaier, B. [Energy Transfer] Luminescent Materials [91–107] (Springer, Berlin, 1994).

Yao, Q. et al. Electric field-induced giant strain and photoluminescence-enhancement effect in rare-earth modified lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 5066–5075, 10.1021/acsami.5b00420 (2015).

Zhang, Q., Sun, H., Zhang, Y. & Ihlefeld, J. Polarization-Induced Photoluminescence Quenching in (Ba0.7Ca0.3TiO3)-(BaZr0.2Ti0.8O3):Pr Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 97, 868–873, 10.1111/jace.12719 (2014).

Tian, X. et al. Remanent-polarization-induced enhancement of photoluminescence in Pr3+-doped lead-free ferroelectric (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3 ceramic. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 042907, 10.1063/1.4790290 (2013).

Wu, X., Lin, M., Lau, C. M. & Kwok, K. W. In Adv. Sci. Technol. 19–24 (Trans Tech Publ).

Gong, S. et al. Phase-Modified Up-Conversion Luminescence in Er-Doped Single-Crystal PbTiO3Nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 5486–5493, 10.1021/jp500492k (2014).

Khatua, D. K., Kalaskar, A. & Ranjan, R. Tuning Photoluminescence Response by Electric Field in Electrically Soft Ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 117601, 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.117601 (2016).

Liu, W. & Ren, X. Large piezoelectric effect in Pb-free ceramics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 257602, 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.257602 (2009).

Vecht, A. New electron excited light emitting materials. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., B 12, 781, 10.1116/1.587346 (1994).

Diallo, P., Boutinaud, P., Mahiou, R. & Cousseins, J. Red luminescence in Pr3+-doped calcium titanates. Phys. Status Solidi A 160, 255–264 (1997).

Yao, Q. et al. Piezoelectric/photoluminescence effects in rare-earth doped lead-free ceramics. Appl. Phys. A 113, 231–236, 10.1007/s00339-012-7524-z (2013).

Peng, D. et al. Blue excited photoluminescence of Pr doped CaBi2Ta2O9 based ferroelectrics. J. Alloys Compd. 511, 159–162, 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.09.019 (2012).

Wan, X. et al. Electro-optic characterization of tetragonal (1−x)Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-xPbTiO3 single crystals by a modified Sénarmont setup. Solid State Commun. 134, 547–551, 10.1016/j.ssc.2005.02.033 (2005).

You, F. et al. 4f5d configuration and photon cascade emission of Pr3+ in solids. J. Lumin. 122–123, 58–61, 10.1016/j.jlumin.2006.01.097 (2007).

G. Blasse, Structure and Bonding, 26, Springer. Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1976).

Piper, W., DeLuca, J. & Ham, F. Cascade fluorescent decay in Pr3+-doped fluorides: Achievement of a quantum yield greater than unity for emission of visible light. J. Lumin. 8, 344–348 (1974).

Zou, H. et al. Polarization-induced enhancement of photoluminescence in Pr3+ doped ferroelectric diphase BaTiO3-CaTiO3 ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 073103, 10.1063/1.4818793 (2013).

Zhang, P. et al. Pr3+ photoluminescence in ferroelectric Ba0.77Ca0.23TiO3ceramics: Sensitive to polarization and phase transitions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 222908, 10.1063/1.2938721 (2008).

Du, P., Luo, L., Li, W., Zhang, Y. & Chen, H. Photoluminescence and piezoelectric properties of Pr-doped NBT–xBZT ceramics: Sensitive to structure transition. J. Alloys Compd. 559, 92–96, 10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.01.096 (2013).

Zhou, H., Wu, G., Qin, N., Bao, D. & Wang, H. Improved Electrical Properties and Strong Red Emission of Pr3+-Doped xK0.5Bi0.5TiO3-(1−x)Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Lead-Free Ferroelectric Thin Films. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 95, 483–486, 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.05028.x (2012).

Wei, Y. et al. Dual-enhancement of ferro-/piezoelectric and photoluminescent performance in Pr3+ doped (K0.5Na0.5)NbO3 lead-free ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 042902, 10.1063/1.4891959 (2014).

Sun, H. L. et al. Correlation of grain size, phase transition and piezoelectric properties in Ba0.85Ca0.15Ti0.90Zr0.10O3 ceramics. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 26, 5270–5278, 10.1007/s10854-015-3063-7 (2015).

Keeble, D. S., Benabdallah, F., Thomas, P. A., Maglione, M. & Kreisel, J. Revised structural phase diagram of (Ba0.7Ca0.3TiO3)-(BaZr0.2Ti0.8O3). Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 092903, 10.1063/1.4793400 (2013).

Tian, Y., Wei, L., Chao, X., Liu, Z. & Yang, Z. Phase Transition Behavior and Large Piezoelectricity Near the Morphotropic Phase Boundary of Lead-Free (Ba0.85Ca0.15)(Zr0.1Ti0.9)O3 Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96, 496–502 (2013).

Pinel, E., Boutinaud, P. & Mahiou, R. What makes the luminescence of Pr3+ different in CaTiO3 and CaZrO3? J. Alloys Compd. 380, 225–229, 10.1016/j.jallcom.2004.03.048. (2004).

Judd, B. R. Optical Absorption Intensities of Rare-Earth Ions. Phys. Rev. 127, 750–761, 10.1103/PhysRev.127.750 (1962).

Ofelt, G. S. Intensities of Crystal Spectra of Rare-Earth Ions. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 511, 10.1063/1.1701366 (1962).

Daniels, J. E., Jo, W., Rödel, J., Honkimäki, V. & Jones, J. L. Electric-field-induced phase-change behavior in (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3-BaTiO3-(K0.5Na0.5)NbO3: A combinatorial investigation. Acta Mater. 58, 2103–2111, 10.1016/j.actamat.2009.11.052 (2010).

Coey, J., Viret, M., von & Von Molnar, S. Mixed-valence manganites. Adv. Phys. 58, 571–697 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (PolyU 152069/14E).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.S., X.W. and T.H.C. performed the experiments. H.L.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. K.W.K. advised on optimizing the ferroelectric materials and tunable PL aspect of the study and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results and revision on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, H., Wu, X., Chung, T. et al. In-situ Electric Field-Induced Modulation of Photoluminescence in Pr-doped Ba0.85Ca0.15Ti0.90Zr0.10O3 Lead-Free Ceramics. Sci Rep 6, 28677 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28677

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28677

This article is cited by

-

Fabrication and Optical Properties of (1−x)Bi½Na½TiO3−xEr½Na½TiO3 Solid Solution System

Journal of Electronic Materials (2023)

-

Optical properties of a new binary lead-free ferroelectric semiconductor Bi1/2Na1/2TiO3–Nd1/2Na1/2TiO3 solid solution system

Applied Physics A (2022)

-

Mechanically controlled reversible photoluminescence response in all-inorganic flexible transparent ferroelectric/mica heterostructures

NPG Asia Materials (2019)

-

Photoluminescence activity of BaTiO3 nanocubes via facile hydrothermal synthesis

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.