Abstract

The interfacial hydration structure of yttria-stabilized cubic zirconia (110) surface in contact with water was determined with ~0.5 Å resolution by high-resolution X-ray reflectivity measurement. The terminal layer shows a reduced electron density compared to the following substrate lattice layers, which indicates there are additional defects generated by metal depletion as well as intrinsic oxygen vacancies, both of which are apparently filled by water species. Above this top surface layer, two additional adsorbed layers are observed forming a characteristic interfacial hydration structure. The first adsorbed layer shows abnormally high density as pure water and likely includes metal species, whereas the second layer consists of pure water. The observed interfacial hydration structure seems responsible for local equilibration of the defective surface in water and eventually regulating the long-term degradation processes. The multitude of water interactions with the zirconia surface results in the complex but highly ordered interfacial structure constituting the reaction front.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zirconia, ZrO2, has numerous applications, e.g., for gas sensing1, solid oxide fuel cell electrode2,3, bio-medical materials4, to name a few and also plays a critical role to protect zirconium alloy surface in highly corrosive environment, e.g., zirconium alloy cladding in pressurized water reactor5. The oxide degradation and the continuous growth of passive layer are detrimental to the materials integrity, which are directly attributed to the interaction of the surface with water. Thus, knowledge of the detailed interfacial structure such as interfacial hydration, surface relaxation and adsorption of ions is of fundamental importance for understanding the degradation mechanism.

For many decades, researchers have studied the degradation of zirconia in relation to the phase transformation. Kobayashi et al.6 first reported the transformation of tetragonal to monoclinic structure after heating above 1,400 °C for several hours. It was also shown that chemically stabilized zirconia (3% mole Y2O3 in ZrO2) undergo hydrothermal degradation from tetragonal to monoclinic in humid condition even at temperatures as low as 100 °C7. A higher dopant rate of cubic phase yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) also showed phase transformation at 250 °C under humid conditions for extended period of time (i.e., over 2 years)8. Recently, Kim et al. used in-situ Raman spectroscopy to confirm the phase transformation of oxide film on zirconium alloy surface under hydrothermal conditions9.

In addition, there has been a great deal of effort to the study of interfacial structures of zirconia in contact with water, attempting to reveal the oxide degradation mechanism from the molecular insight. It is known that water molecules are adsorbed on zirconia surface inducing new OH groups, which remains on the surface as point defects but eventually migrates into the substrate lattice to initiate the degradation process10,11,12. Water is chemisorbed dissociatively on surfaces of zirconia, revealed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry13. Dissolution of the oxide layer on zirconium surface is also suspected as a possible breakdown mechanism under high temperature condition14. A first-principle study of the hydroxylation of zirconia surface suggests generally more favorable adsorption of dissociative water than molecular water on zirconia surface, especially, at low coverage15. Dynamics of the surface water molecules studied by a quasi-elastic neutron-scattering technique, however, suggests co-existing water modes on the ZrO2 surface in addition to the surface hydroxyl OH groups16,17. Inelastic neutron and Raman scattering studies also show the existence of chemisorbed hydroxyl groups and physisorbed water simultaneously on surface of ZrO2 nanoparticles18,19.

Similar mechanisms on YSZ in contact with water were also studied. Yoshimura et al. proposed a degradation process of YSZ by H2O to form OH− on the surface which initiates the stressed sites20. Raz et al. also studied the adsorption of water layers on YSZ and suggested the first water layer to be chemisorbed on the Zr sites and the second layer to be physisorbed on top of the chemisorbed water layer21. The cubic form of YSZ were also found to form hydroxyl groups on the surface22. Degradation during aging of transformation-toughened YSZ at 250 °C was reported, caused by depletion of dopant metal when exposed to water vapor23. Costa et al. studied the energetics of water adsorption on YSZ surfaces to reveal the reduction of anhydrous surface energy by adsorbing water on the surface24.

These studies of zirconia-water interfaces have brought into great knowledge about the initiation mechanism of the degradation and corrosion processes. The results can be summarized into two main opinions: firstly, the degradation process under humid conditions starts from the water chemisorption on the surface Zr sites, which creates point defects; secondly, the degradation process involves the leach of the dopant metal ions, which makes the crystal structure unstable and therefore undergoes phase transformation. Despite the extensive studies, these two opinions hardly found their consensus25, suggesting the lack of knowledge on the experimentally determined structure of the zirconia-water interface at the molecular scale.

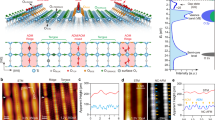

Here we use the high-resolution X-ray reflectivity (HRXR) to determine the interfacial hydration structure at YSZ (110)-water interface with atomic scale resolution. Over the past three decades, this synchrotron-based X-ray reflectivity technique has emerged and been developed into a very sophisticated and cutting-edge method for probing the interfacial structures with sub-Ångström resolution26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Detailed hydration structures and molecular level processes at various mineral-water interfaces have been studied with this technique. We utilize a single crystal YSZ substrate because the HRXR technique requires an atomically flat and homogenous solid surface for allowance of measuring the intensities consistently over a wide range of reflection angles. The nearly perfect single crystal YSZ substrates are commercially available, while zirconia crystal is only stable in monoclinic form at T < 1,170 °C33 and the high purity single crystal zirconia is difficult to obtain from melt due to its large volume expansion from tetragonal to monoclinic transformation34. Therefore, we take an advantage of YSZ’s crystallinity to bypass those difficulties and at the same time exploit its own merit as a model system representing defective zirconia surface.

The unit cell of cubic YSZ along (110) direction exhibits tetragonal structure (a = c = 3.642 Å and b = 5.152 Å). Figure 1 shows the crystal structure of the cubic ZrO2 in (110) direction from both top and side views. There is only one physically possible termination of the surface in this particular orientation, where both metal and oxygen species are exposed. In this study, we measure the HRXR from the YSZ (110)-water interface at ambient condition with a specular θ-2θ scan geometry. The schematic illustration of the thin film sample cell in use and the experimental geometry for the X-ray reflectivity measurement are depicted in Fig. 2. We performed a non-linear least squares fitting to the experimental data to derive the electron density profile along the surface normal direction. The detailed structure including the termination of the YSZ (110) surface and the characteristic interfacial hydration was obtained. Our result reveals multitude of water interaction with the surface: filling the vacancies from intrinsic oxygen deficiency and surface metal depletion, locally hydrating and stabilizing surface metal species and spatially confining the interfacial hydration process within a few molecular layers of water resulting in a highly ordered interfacial structure.

Crystal structure of cubic ZrO2.

(a) Top view of (110) surface and (b) side view with indication of the unit cell redefined for this particular orientation (solid rectangle). Teal spheres represent metal atoms and red spheres oxygen atoms. With 8% mole Y2O3 doping, the metal atom sites consist of 14.8% Y and 85.2% Zr atoms and the oxygen sites have occupancy of 96.3%.

Results

High-resolution X-ray reflectivity

Figure 3 shows the measured specular HRXRs and their best-fit results for two different YSZ (110) substrates (Sample #1 and Sample #2) in contact with water as a function of momentum transfer Qz = 4πsinθ/λ, where θ is the X-ray incident angle and λ is the wavelength. The measured data spans from Qz = 0.70 through 5.95 Å−1. Since the Bragg reflection of face-centered cubic (110) is forbidden35, the first Bragg peak corresponds to the (220) refection at Qz = 2π/d220 = 3.45 Å−1. The spatial resolution in the corresponding real-space structure is determined by the maximum Qz, which gives an FWHM resolution of π/Qz, max = 0.53 Å assuming a Gaussian distribution. Compared to Sample #1, the reflectivity data from Sample #2 appears to have lower mid-zone intensities. This behavior is observed when the fractional occupancy of adsorbed layer at the interface is different31. The detailed quantitative analysis based on the interfacial structure factor model is given in the following sections.

We performed Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) measurement to test the surface morphologies and roughness (Fig. S1). The AFM measurement confirms that the two samples have certainly different morphologies but commonly lack the distinct steps, kinks and ledges on the surface. The root-mean square (r.m.s.) roughness is 2.4 Å for Sample #1 and 1.0 Å for Sample #2, respectively. Considering the physical unit cell height (d220 = 1.82 Å), the both samples show quite smooth surface but with extended non-uniformity without distinct lateral boundaries (see Supplementary Information).

Structure factor analysis and the best-fit result

The detailed description of the HRXR analysis for solid-water interface can be found in the review articles30,31. The measured reflectivity can be reproduced by a structure factor model based on the known crystal structure of solid substrate and a few modeling strategies for the interface:

Although the structure factor model (Eq. (1)) consists of three terms, it represents four major physical components from the solid-water interface: (1) the semi-infinite single crystal, (2) the near surface unit cells which deviate to any extent from the bulk, e.g., relaxation in the d-spacing, depletion, etc., (3) the adsorbed layers containing water and other species such as ions and (4) the semi-infinite bulk water. In Equation (1), Fsub·uc(Qz)·FCTR(Qz) corresponds to component (1), Finterface(Qz) includes both (2) and (3) and Fwater(Qz) represents component (4). The intensities measured at the mid-zone regions between Bragg peaks are more sensitive to the interfacial structure, while the near-Bragg regions are more influenced by the single crystal substrate. The interfacial structure can be determined through non-linear least squares fitting to the measured X-ray reflectivity data using a set of model structure factor parameters. The electron density profile for each scattering atom is modeled by a Gaussian distribution, whose FWHM defines the spatial resolution. The experimental resolution, determined by the maximum measured Qz,max, is convoluted to the total electron density profile when it is reconstructed based on the best-fit model. The exact expressions and the detailed modeling strategies can be found in SI.

In Fig. 3, the best-fit results reproduce both measured X-ray reflectivity data very well. The chi-square, defined as χ2 = ∑i(Icalc.,i − Imeas.,i)2/[σi2(N−P)] where Icalc.,i is the calculated intensity, Imeas.,i is the measured intensity, σi is the standard error of the measured data, N is the number of data points and P is the number of parameters, respectively36, from the least-squares fitting is 1.159 and 1.398 for Sample #1 and Sample #2, respectively. The electron density profiles along the surface normal direction are then derived based on the best-fit parameters (listed in Table S1 in SI). Figure 4a shows the ball and stick model of the atomic structures depicting the most-likely scenario for the interfacial hydration processes and Fig. 4b is the corresponding electron density profiles (black line for Sample #1 and red dashed line for Sample #2). The profiles represent the laterally averaged electron densities.

Interfacial structure and most-likely scenario of interfacial processes.

(a) Ball and stick model of the atomic structures depicting the most-likely scenario of the interfacial hydration processes: blue filled circles with two red ear small circles represent water molecules, green filled circles represent yttrium, teal filled circles represent zirconium, red filled circles represent oxygen and unfilled circles represent oxygen vacancies in the bulk. The green arrow shows the possible Y dissolution and re-adsorption process and the orange line indicates M-O bonding; and (b) the electron density profile derived based on the best-fit parameters estimated to reproduce the measured HRXR data. The sub-profiles are expressed only for Sample #1 for clarity.

Despite the distinct difference observed in the measured HRXR spectra, the resultant interfacial structures as shown by electron density profiles (Fig. 4b) are surprisingly consistent with each other except for relatively higher total density at the position of second adsorbed layer for Sample #1, which should be correspondingly responsible for the promoted intensities at the mid-zone. However, according to the estimated values and errors listed in Table S1, the difference is indistinguishable within the errors. It is true not only for the particular layer parameters but also for all other parameters. The model parameters were chosen to reproduce both of the measured data with an identical definition and the minimum required number of parameters to avoid large covariance between the parameters. Therefore, the qualitatively consistent features (Fig. 4b) observed from two independent measurements, which show statistically significant differences (Fig. 3), are meaningful to confirm the general characteristics of the YSZ (110)-water interface structure. Other sets of parameters specific to each sample were also tested, which reproduced similar total electron density profiles.

The two samples show similar hydration structures with an adsorbed water layer overlapping the terminal layer (at z = 0 in Fig. 4) followed by the two additional layers before connected to the bulk water. The surface roughness of these two samples, as calculated from the estimated Robinson factors26, turned out to be very close to each other, 1.34 Å and 1.38 Å for Sample #1 and Sample #2, respectively. These values are different from the r.m.s ones obtained by the AFM measurements, which suggests that the general characteristics for YSZ (110)-water interface structure observed in this study are independent of the surface morphology.

Interfacial structure

For the surface relaxation, the best-fit results show alternating positive and negative relaxations in the lattice parameters of the top five surface unit cells (a1 through a5, Table S1). However, the variations are negligibly small, less than 0.01 Å displacement from the bulk unit cell lattice constant (<0.3% uniaxial strain per each unit cell). Compared to an ab-initio calculation result which reports ~0.2 Å top surface relaxation followed by 0.09 Å next layer for anhydrous YSZ (110) surface37, the observed relaxations are remarkably small.

At the terminal layer of substrate (z = 0), the metal occupancy is found to be 0.728 ± 0.063 for Sample #1 (~27% depletion from the ideal occupancy 1) (Table S1 in SI). The position of O at the top surface is found to be slightly displaced from that of the metal atoms at Δy = −0.007 ± 0.052 Å. The best-fit results show also a layer of O equivalent (i.e., estimated by an oxygen occupancy), vacancy-filling water overlapping the terminal layer (dashed blue line in Fig. 4b) with distribution width of 0.132 ± 0.047 Å. The detailed explanation for the fitting parameters to represent these highly overlapping features at the same position is given in SI.

Above the terminal layer, there are two additionally adsorbed layers found at z1 = 1.687 ± 0.048 Å (dashed gold line) and z2 = 3.439 ± 0.118 Å (dashed purple line), respectively. The first adsorbed layer has abnormally high density to be a pure water layer; therefore, it probably includes higher density species such as metal atoms. The second adsorbed layer is presumably pure water layer as its density is comparable to that of pure water. The interfacial hydration structure is then followed by the sharp first layer of bulk water at 4.918 ± 1.019 Å above the substrate surface (or 1.479 Å above the 2nd adsorbed layer) and quickly damps into the featureless bulk structure31,38 (dashed green line in Fig. 4b).

When characterizing the adsorbed hydration structures next to the terminal layer, we initially assumed pure water for these layers. The best-fit results, however, yielded unphysically dense first adsorbed layer as a pure water layer, 2.65 times of the bulk water density (at z1 = ~1.7 Å in Fig. 4b). This result suggests that this hydration layer include additionally heavier species than water such as Zr or Y atoms, or both. Each metal atom has about 4 times electrons (40 or 39) of water (10), therefore, 2.65 times of bulk water density corresponds to only a fraction (~0.66) of metal occupancy in this layer. The unit cell has an occupancy of 1 metal and 2 oxygen atoms (total 3 atoms) on each plane; therefore, there is still enough space for water molecules to fill in in this layer. Consequently, the metal atoms in this layer are likely surrounded by water molecules, with the possibility of forming extra M-O bonding with the substrate surface O atom and water in the 2nd adsorbed layer in its three dimensional configuration. We modeled them as a hydrated metal species, [M(H2O)n]x+, where n represents the hydration shell of the metal species and x represents the possible valence of the hydrated complex. The inclusion of the metal ions in the first adsorbed layer turned out to reproduce the measured data very well. However, due the similar electron numbers of Y and Zr, modeling based on either complex turned identical. Table S1 reports one of the tested models as a representative for simplicity.

Sample #2 results reproduce the qualitatively same features as described in the previous section. The following discussions are based on Sample #1 results.

Discussion

At the terminal layer, the metal depletion, as observed (~27%), should result in a substantial increase in the number of vacancies in addition to the inherent vacancies39. These vacancy sites, regardless of their origins, are expected to be occupied by “vacancy filling” water40 and they are likely to be dissociated based on numerous pre-existing contexts10,11,12,13,15,16,17,18,19,21. A recent density functional study supports that, although along the different orientation of (111), water molecules are expected to be strongly chemisorbed on the YSZ surface, too41. Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that at least a portion of this vacancy filling water (blue dashed line in Fig. 4b) should be dissociative and chemisorbed on the surface to form hydroxide. The best-fit value for the distribution width of this layer is 0.132 ± 0.047 Å (Table S1), which indicates quite narrowly confined geometry for the adsorption. It is also worth pointing out that the metal depletion is limited on the top surface layer in our model. The water species confined in this layer may be related to the process relevant to reducing the interfacial energy relative to the anhydrous surface24, although the role of other two adsorbed layers should be considered together.

The origin of the suspected metal species in the first adsorbed hydration layer lies in two possibilities. Firstly, it could come from re-adsorption of dissolved Y from the substrate. The leaching of Y from the substrate42 would generate a pair of freed Y3+ and a negatively charged vacancy left behind. Although the vacancy could be filled by water molecule, its valence could be only reduced to −2 at most as the water could only be positively monovalent (in the form of hydronium H3O+). Therefore, there will be still a relatively strong electrostatic interaction between the Y3+ and the negative vacancy site, which will greatly restrain the Y3+ from leaving the substrate surface. In addition, the formation of hydration structure and the possible Y-O bonding with surface O atoms would help greatly in reducing the surface energy to keep this configuration stable. The green arrow and orange line in Fig. 4a indicate these two processes. Secondly, the observed layer could be simply an “adlayer” or partial layer as another form of defect, which, different from what its name implies, might be produced by an extended depletion in lateral direction. As the crystalline layer for this particular orientation is a composite metal-oxygen layer allowing only one possible termination (Figs 1 and 4b), these two possibilities are undistinguishable. So the identity of metal species in this layer still remains unclear. The position of this layer (1.687 Å, Table S1) is, however, significantly lower compared to the crystalline layer spacing (1.821 Å). It is rather closer to the layer spacing of tetragonal ZrO2 in (100) orientation (1.793 Å)43, which has the same coordination characteristics with that of YSZ (110). Because of this large discrepancy from both crystalline layer spacing, it is not quite strongly supported that this layer is from crystalline adlayer. Nevertheless, the observed interfacial structure is stable at least for the short experimental time period of ~8 hrs (the experimental duration).

Immediately above the dense 1st adsorbed layer, the best-fit results show an additionally adsorbed water layer with occupancy of 1.441 ± 0.347. The existence of the ordered second hydration layer is qualitatively consistent with the basic assumption that the vacancy filling by water and the metal-hydration interactions at the interface should strongly constrain the next layer hydration (see Interfacial Structure Factor Modeling Strategies in SI). Compared to the natural olivine (010)-water interface40, the first adsorbed layer at the YSZ (110)-water interface even includes heavier metal species besides water so that the different chemistry effect must be considered. Nevertheless, the existence of the sharp second hydration layer is characteristic to the interfacial hydration structure of our system. In Fig. 4b, the total density of this layer looks slightly higher than that expected for the normal water, although the estimated water occupancy is slightly less than expected (~1.876 per 18.76 Å2 for bulk water). The apparently promoted electron density seems due to its highly ordered but overlapping neighboring layers which have wide distribution widths (purple dashed line in Fig. 4b).

The first layer of bulk water (green dashed line in Fig. 4b) is followed by nearly featureless bulk water next to it, restoring the bulk water structure immediately. It is worth remarking that the transition from highly ordered interfacial water to disordered bulk water takes only one transitional layer. And also, the large overlapping between the ordered adsorbed layer and the transitional bulk water layer (i.e., the first bulk water layer) indicates a degenerate portion of the layered adsorbed water (the 2nd adsorbed layer) and this transitional bulk water.

In conclusion, the structure of YSZ (110)-water interface was determined with high-resolution X-ray reflectivity. The best-fit structure suggests that the surface relaxation is negligible while the terminal layer, metal and oxygen terminated, includes a significant number of point defects indicated by the reduction of total electron density. The intrinsic oxygen vacancy sites and those generated by metal depletion are expected to be filled by water with significant amount of water being dissociative. Two distinct adsorbed layers on top of the terminal layer further characterize the interfacial hydration structure. The first adsorbed layer likely includes metal species, while the second adsorbed layer consists of pure water. There have been numerous studies showing the water chemisorption on zirconia surfaces as an important primary process for the degradation. Our study provides the detailed geometric confinement and how they are correlated with the molecularly adsorbed water. The entire interfacial hydration process is spatially confined within three molecular layers of water resulting in highly ordered layer structure. Therefore, our results suggest a possibility that a stabilization of this characteristic interfacial hydration structure, e.g., by tweaking water chemistry, would mitigate further degradation. This possibility gives us a unique opportunity to reconsider the passivation mechanism and a feasible route to control the process ultimately. The detailed elemental profile with quantitative coverage information is desired to investigate this possibility further.

Methods

Materials

Single crystal yttria-stabilized cubic zirconia (8% mole Y2O3), or YSZ, substrates were purchased from MTI Corporation in the dimension of 10 × 10 × 0.5 mm3. The orientation accuracy as estimated during the HRXR measurement is ~0.9° and the r.m.s. surface roughness is 2.4 Å for Sample #1 and 1.0 Å for Sample #2, respectively, as characterized by an atomic force microscopy (see SI). The crystal system is CaF2 type face centered cubic. We determined the lattice constant, 5.152 ± 0.010 Å, during our HRXR measurement. Along the surface normal direction, [110], the surface unit cell exhibits a tetragonal structure (Fig. 1). The d-spacing of surface unit cell reduces to 1/√2 of the original unit cell, i.e., d110 = 3.642 Å. In this paper we refer the “unit cell” to this surface unit cell and “occupancy” refers to per unit cell area of 18.76 Å2 (a = 5.152 Å × b = 3.642 Å). The unit cell consists of a fraction of ½ Zr and 1 O atoms at z = 0 plane, 1 Zr and 2 O atoms at z = 1/2d110 plane and ½ Zr and 1 O atoms at z = d110 plane. Along z direction, the stacking of unit cell results in periodic arrangement of 1 Zr and 2 O atoms on each plane. Therefore, there exists only one possible termination surface (Fig. 1).

Sample preparation

The substrate was cleaned ultrasonically in acetone, methanol and deionized water (DIW) for >15 min each successively to remove any possible organic contaminations before use. At the final stage of cleaning, the sample was extensively cleaned in more than 300 mL DIW with sonicating to remove remnant methanol on surface, which is known to be strongly adsorbed on zirconia surface. The cleaned substrate was then mounted in a thin-film cell designed for in-situ HRXR measurement from a solid-liquid interface (Fig. 2). The sample was covered and held in place by an 8-μm thick Kapton film on a plastic (PEEK) cell base. The Kapton cover was inflated by purging DIW to fully wet the substrate surface and the cell was repeatedly flushed to completely remove air bubbles and other remnant, if any. The cell was then naturally drained by the gravitational force to form a thin water film (less than a few tens of microns) between the YSZ (110) surface and the Kapton film for the HRXR measurement. The cell was then sealed by close valves during the measurement without water flowing through it hence remained as an isolated state at room temperature.

High resolution X-ray reflectivity

The HRXR measurement for Sample #1 was carried out at the 33-ID-D beamline of Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory (ANL). The incident X-ray energy was 21.000 keV, the beam was focused with Kirkpatrick-Baez mirrors to 0.05 mm (v) × 0.2 mm (h) and the incident flux was ~1011 photons/sec. The HRXR for Sample #2 from a different batch was carried out at beamline 9C of Pohang Light Source (PLS) at Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL) in South Korea. The incident X-ray energy was 15.000 keV. The beam was collimated to 0.1 mm (v) × 0.7 mm (h) and the incident flux was ~1.1 × 1011 photons/sec. A Pilatus 100K detector, mounted on a 4-circle diffractometer arm, was used to collect the data. The scattering area on the detector was defined by a set of detector slits. The HRXR from YSZ (110)-water interface was measured in a specular θ-2θ scan geometry. The data reduction from the area detector followed the description by Fenter et al.44. A set of guard slits were used for the reduction of background scattering. The measured intensities were normalized by an incident beam monitor. The errors are propagated from the counting statistics.

Atomic force microscopy

The Atomic Force Microscopy (Asylum Research MFP3D, Santa Barbara, CA) was used to examine the surface morphologies of the samples. The AFM was operated in contact mode to ensure atomic level resolution for probing the height distribution. The loading force was 81.4 nN and the scan rate was 0.8 Hz.

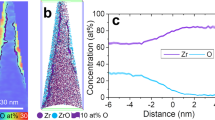

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

The XPS measurements were carried out with a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer. The first XPS measurement was done on the as-cleaned single crystal substrate and then followed by several measurements after sputtering time of 2, 4, 6 and 20 seconds, respectively. The binding energies were calibrated with the adventitious C 1s peak at 284.6 eV.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hou, B. et al. The Hydration Structure at Yttria-Stabilized Cubic Zirconia (110)-Water Interface with Sub-Ångström Resolution. Sci. Rep. 6, 27916; doi: 10.1038/srep27916 (2016).

References

Maskell, W. C. Progress in the development of zirconia gas sensors. Solid State Ionics 134, 43–50, 10.1016/S0167-2738(00)00712-8 (2000).

An, J. et al. Aberration-Corrected TEM Imaging of Oxygen Occupancy in YSZ. J Phys Chem Lett 4, 1156–1160, 10.1021/jz4002423 (2013).

He, X. D., Meng, B., Sun, Y., Liu, B. C. & Li, M. W. Electron beam physical vapor deposition of YSZ electrolyte coatings for SOFCs. Appl Surf Sci 254, 7159–7164, 10.1016/j.apsusc.2008.05.271 (2008).

Le Coadou, C. et al. Assessment of ultrathin yttria-stabilized zirconia foils for biomedical applications. J Mater Sci 50, 6197–6207, 10.1007/s10853-015-9178-7 (2015).

Rickover, H. G., Geiger, L. D. & Lustman, B. Histroy of the development of zirconium alloys for use in nuclear reactors. Report No. TID–26740, (Washington DC, 1975).

Kobayashi, K., Kuwajima, H. & Masaki, T. Phase-Change and Mechanical-Properties of ZrO2-Y2O3 Solid Electrolyte after Aging. Solid State Ionics 3–4, 489–493, 10.1016/0167-2738(81)90138-7 (1981).

Guo, X. Hydrothermal degradation mechanism of tetragonal Zirconia. J Mater Sci 36, 3737–3744, 10.1023/A:1017925800904 (2001).

Guo, X. & He, J. Q. Hydrothermal degradation of cubic zirconia. Acta Mater 51, 5123–5130, 10.1016/S1359-6454(03)00362-8 (2003).

Kim, T. et al. Phase transformation of oxide film in zirconium alloy in high temperature hydrogenated water. Corrosion Science 99, 134–144, 10.1016/j.corsci.2015.06.034 (2015).

Jacob, K. H., Knozinger, E. & Benier, S. Adsorption Sites on Polymorphic Zirconia. J Mater Chem 3, 651–657, 10.1039/JM9930300651 (1993).

Agron, P. A., Fuller, E. L. & Holmes, H. F. IR studies of water sorption on ZrO2 polymorphs. I. J Colloid Interf Sci 52, 553–561, 10.1016/0021-9797(75)90280-5 (1975).

Merle-Mejean, T., Barberis, P., Othmane, S. B., Nardou, F. & Quintard, P. E. Chemical forms of hydroxyls on/in zirconia: An FT-IR study. J Eur Ceram Soc 18, 1579–1586, 10.1016/S0955-2219(98)00080-6 (1998).

Ignatchenko, A., Nealon, D. G., Dushane, R. & Humphries, K. Interaction of water with titania and zirconia surfaces. J Mol Catal a-Chem 256, 57–74, 10.1016/j.molcata.2006.04.031 (2006).

Nishino, Y., Endo, M., Ibe, E. & Yasuda, T. Formation and dissolution of oxide film on zirconium alloys in 288 degrees C pure water under gamma-ray irradiation. J Nucl Mater 248, 292–298, 10.1016/S0022-3115(97)00126-8 (1997).

Iskandarova, I. M. et al. First-principle investigation of the hydroxylation of zirconia and hafnia surfaces. Microelectron Eng 69, 587–593, 10.1016/s0167-9317(03)00350-2 (2003).

Mamontov, E. Dynamics of surface water in ZrO2 studied by quasielastic neutron scattering. J Chem Phys 121, 9087–9097, 10.1063/1.1804152 (2004).

Mamontov, E. High-resolution neutron-scattering study of slow dynamics of surface water molecules in zirconium oxide. J Chem Phys 123, 024706, 10.1063/1.1949171 (2005).

Ozawa, M., Suzuki, S., Loong, C. K. & Nipko, J. C. Neutron and Raman scattering studies of surface adsorbed molecular vibrations and bulk phonons in ZrO2 nanoparticles. Appl Surf Sci 121, 133–137, 10.1016/S0169-4332(97)00272-9 (1997).

Loong, C. K., Richardson, J. W. & Ozawa, M. Crystal phases, defects and dynamics of adsorbed hydroxyl groups and water in pure and lanthanide-modified zirconia: A neutron-scattering study. J Catal 157, 636–644, 10.1006/jcat.1995.1329 (1995).

Yoshimura, M., Noma, T., Kawabata, K. & Somiya, S. Role of H2O on the Degradation Process of Y-TZP. J Mater Sci Lett 6, 465–467, 10.1007/Bf01756800 (1987).

Raz, S., Sasaki, K., Maier, J. & Riess, I. Characterization of adsorbed water layers on Y2O3-doped ZrO2 . Solid State Ionics 143, 181–204, 10.1016/S0167-2738(01)00826-8 (2001).

Guo, X. Low temperature stability of cubic zirconia. Phys Status Solidi A 177, 191–201, 10.1002/(Sici)1521-396x(200001)177:1<191::Aid-Pssa191>3.0.Co;2-X (2000).

Lange, F. F., Dunlop, G. L. & Davis, B. I. Degradation during Aging of Transformation-Toughened ZrO2-Y2O3 Materials at 250 °C. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 69, 237–240, 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1986.tb07415.x (1986).

Costa, G. C. C., Ushakov, S. V., Castro, R. H. R., Navrotsky, A. & Muccillo, R. Calorimetric Measurement of Surface and Interface Enthalpies of Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia (YSZ). Chem Mater 22, 2937–2945, 10.1021/cm100255u (2010).

Cox, B. Some thoughts on the mechanisms of in-reactor corrosion of zirconium alloys. Journal of Nuclear Materials 336, 331–368, 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2004.09.029 (2005).

Robinson, I. K. Crystal Truncation Rods and Surface-Roughness. Phys. Rev. B 33, 3830–3836, 10.1103/PhysRevB.33.3830 (1986).

Chiarello, R. P. & Sturchio, N. C. Epitaxial-Growth of Otavite on Calcite Observed in-Situ by Synchrotron X-Ray-Scattering. Geochim Cosmochim Ac 58, 5633–5638, 10.1016/0016-7037(94)90255-0 (1994).

Geissbuhler, P. et al. Three-dimensional structure of the calcite-water interface by surface X-ray scattering. Surf. Sci. 573, 191–203, 10.1016/j.susc.2004.09.036 (2004).

Park, C. Y., Fenter, P., Zhang, Z., Cheng, L. W. & Sturchio, N. C. Structure of the fluorapatite (100)-water interface by high-resolution X-ray reflectivity. Am. Mineral. 89, 1647–1654, 10.2138/am-2004-11-1209 (2004).

Fenter, P. & Sturchio, N. C. Mineral-water interfacial structures revealed by synchrotron X-ray scattering. Prog Surf Sci 77, 171–258, 10.1016/j.progsurf.2004.12.001 (2004).

Fenter, P. A. X-ray reflectivity as a probe of mineral-fluid interfaces: A user guide. Rev Mineral Geochem 49, 149–220, 10.2138/gsrmg.49.1.149 (2002).

Lee, S. S., Fenter, P., Nagy, K. L. & Sturchio, N. C. Monovalent Ion Adsorption at the Muscovite (001)-Solution Interface: Relationships among Ion Coverage and Speciation, Interfacial Water Structure and Substrate Relaxation. Langmuir 28, 8637–8650, 10.1021/La300032h (2012).

Stevens, R. In in Zirconia and Zirconia Ceramics 28–43 (Magnesium Elektron, 1986).

Scheel, H. J. & Fukuda, T. Crystal Growth Technology. (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2003).

Als-Nielsen, J. & McMorrow, D. Elements of Modern X-Ray Physics. (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2001).

Bevington, P. R. & Robinson, D. K. Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences. (McGraw Hill, 1992).

Ballabio, G., Bernasconi, M., Pietrucci, F. & Serra, S. Ab initio study of yttria-stabilized cubic zirconia surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 70, 075417, 10.1103/PhysRevB.70.075417 (2004).

Magnussen, O. M. et al. X-Ray Reflectivity Measurements of Surface Layering in Liquid Mercury. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4444–4447, 10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.4444 (1995).

Stapper, G., Bernasconi, M., Nicoloso, N. & Parrinello, M. Ab initio study of structural and electronic properties of yttria-stabilized cubic zirconia. Phys Rev B 59, 797–810, 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.797 (1999).

Yan, H. P. et al. Termination and hydration of forsteritic olivine (010) surface. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta 145, 268–280, 10.1016/j.gca.2014.09.005 (2014).

Chaopradith, D. T., Scanlon, D. O. & Catlow, C. R. A. Adsorption of Water on Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 119, 22526–22533, 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b06825 (2015).

Adair, J. H., Krarup, H. G., Venigalla, S. & Tsukada, T. A Review of the Aqueous Chemistry of the Zirconium - Water System to 200 °C. MRS Proceedings 432, 101–112, 10.1557/PROC-431-101 (1996).

Yashima, M. & Tsunekawa, S. Structures and the oxygen deficiency of tetragonal and monoclinic zirconium oxide nanoparticles. Acta Crystallogr B 62, 161–164, 10.1107/S0108768105030570 (2006).

Fenter, P., Catalano, J. G., Park, C. & Zhang, Z. On the use of CCD area detectors for high-resolution specular X-ray reflectivity. J. Synchrot. Radiat. 13, 293–303, 10.1107/s0909049506018000 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The work was performed under the auspices of the International Collaborative Energy Technology R&D Program (No. 20138530030010) of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) granted financial resource from the Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy. CP and BH acknowledge support from High Pressure Collaborative Access Team (HPCAT), supported by DOE-NNSA under Award No. DE-NA0001974 and DOE-BES under Award No. DE-FG02-99ER45775. The Advanced Photon Source is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Authors thank Drs. Z. Zhang, E. Karapetrova and C.M. Schlepuetz at the APS Sector 33, C. Kenney-Benson at HPCAT and Drs. S. Lee and Y. Kim at 9C of PLS for their technical supports. Authors also thank Drs. Guoyin Shen and Russell J. Hemley at Geophysical Laboratory of Carnegie Institution of Washington for their illuminative discussions and comments. Authors also thank the anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.P., J.H.K. and C.B.B. designed the experiment. B.H., S.K., T.K., C.P., J.K. and S.H. performed the experiment. B.H. and C.P. analyzed the experimental data and prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revisions of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, B., Kim, S., Kim, T. et al. The Hydration Structure at Yttria-Stabilized Cubic Zirconia (110)-Water Interface with Sub-Ångström Resolution. Sci Rep 6, 27916 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27916

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27916

This article is cited by

-

The role of Y2O3 in the bioactivity of YSZ/PLLA composites

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.