Abstract

CMOS-compatible nonlinear optics platforms with high Kerr nonlinearity facilitate the generation of broadband spectra based on self-phase modulation. Our ultra – silicon rich nitride (USRN) platform is designed to have a large nonlinear refractive index and low nonlinear losses at 1.55 μm for the facilitation of wideband spectral broadening. We investigate the ultrafast spectral characteristics of USRN waveguides with 1-mm-length, which have high nonlinear parameters (γ ∼ 550 W−1/m) and anomalous dispersion at 1.55 μm wavelength of input light. USRN add-drop ring resonators broaden output spectra by a factor of 2 compared with the bandwidth of input fs laser with the highest quality factors of 11000 and 15000. Two – fold self phase modulation induced spectral broadening is observed using waveguides only 430 μm in length, whereas a quadrupling of the output bandwidth is observed with USRN waveguides with a 1-mm-length. A broadening factor of around 3 per 1 mm length is achieved in the USRN waveguides, a value which is comparatively larger than many other CMOS-compatible platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS)-compatible platforms for nonlinear optics offers tremendous benefits to ultrafast all-optical signal processing and light generation1. In particular, nonlinear photonic chips with high Kerr nonlinearity enables low power self phase modulation (SPM), four wave mixing and cross phase modulation which collectively can give rise to the generation of ultrabroadband spectra via supercontinuum generation (SCG), which is applicable to fields including optical coherence tomography2, frequency metrology3, dense wavelength division multiplexed (DWDM) optical networks4 and so on.

Silicon-on-insulator (SOI) has been a popular platform due to high Kerr nonlinearity (typical nonlinear parameters of 100–300 W−1/m) and high refractive index contrast between Si core (nSi = 3.48) and SiO2 cladding () which facilitates tight confinement of light1. However, the nonlinear loss such as two photon absorption (TPA) and free carrier effect in telecommunication band with the wavelengths shorter than about 2000 nm limits the useable power levels and achievable nonlinear phase acquisition5,6. Chalcogenide glasses7,8,9,10 and AlGaAs11,12,13 are also promising platforms possessing high third-order nonlinearities, broadband transparency and low TPA, though limited to applications where CMOS compatibility is not required due to the challenging fabrication for highly efficient waveguides. In this way, CMOS-compatible devices based on these materials are in development.

Silicon nitride (Si3N4)14,15,16,17,18 and Hydex glass are two nonlinear optic platforms which have been used with much success to efficiently reduce nonlinear loss as well as linear loss. These two platforms yield increases in n2 according to Miller’s rule that is solely affected by linear refractive index19. The refractive index contrast between core and cladding is not as high as in SOI, so scattering losses from fabrication induced sidewall roughness can be made to be much smaller. Besides, TPA in silicon nitride and Hydex glass at the near-infrared can be also reduced owing to the large energy bandgap. Therefore, highly stable material and dispersion engineering properties have enabled these platforms to make significant progress within a short amount of time. In particular, frequency comb generations in Si3N4 and Hydex glass have been demonstrated with much success because of relatively higher nonlinear figure or merit than that in SOI20,21,22. However, the nonlinear refractive index is about ten times smaller than that of silicon. Another platform which is becoming more popular for nonlinear optics is silicon rich nitride, which is generally characterized by a refractive index <2.223,24 and according to Miller’s rule, concomitantly lower nonlinear refractive index.

In this paper, we study ultra – silicon rich nitride (USRN) waveguides for their ability to acquire nonlinear phase using ultra – short lengths. The USRN material25,26 is distinguished from the typical silicon rich nitride platform as it is characterized by a much larger linear refractive index (n = 3.1), much larger nonlinear parameters (∼550 W−1/m vs. a few W−1/m) though both have a sufficiently large band gap to eliminate TPA at the 1.55 μm wavelength. The ultrafast spectral characteristics of USRN waveguide structures are investigated. Using the broad spectrum generated with the short waveguide lengths, quality – factors (Q-factors) of a ring resonator are characterized over a wavelength range of almost 200 nm, outside of that typically available using an erbium – based amplified spontaneous emission source. The output spectra at pass ports of USRN ring resonators using a femtosecond fiber source are examined to understand how the resonator Q-factors and spectral bandwidth change. In addition, the short waveguides with a 1-mm-length scale are sufficiently short to be well below the dispersion length and therefore, nonlinear dynamics are predominantly governed by the waveguide’s nonlinearity.

Results

Our USRN film is composed of approximately 2:1 of Si:N ratio that is much more silicon rich than stoichiometric silicon nitride (Si:N = 3:4). USRN waveguides which are 600 nm wide and 300 nm thick possess anomalous waveguide dispersion of around 200 ps/nm/km at 1.55 μm. Waveguides used in this experiment have a length of ∼1 mm. Using the previously measured n2 value of the film25, the nonlinear parameter for this waveguide is calculated to be ∼550 W−1/m. This implies a dispersive length (LD) of 32 cm and a nonlinear length (LNL) of <0.19 mm for peak powers >10 W. Given that the LD is much longer and the LNL is much shorter than the physical waveguide length, the pulse dynamics will be dominated by the nonlinearity rather than dispersion in the waveguide. The large energy bandgap (Eg ∼ 2.1 eV) is also enough to eliminate TPA of the laser centered at 1.55 μm (∼0.8 eV)16.

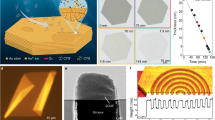

Figure 1(a) depicts the schematic of the experimental setup to observe output spectra of USRN waveguides. Figure 1(b) shows a scanning electron micrograph of the fabricated USRN waveguide. We use a 500 fs fiber laser centered at 1.55 μm with 20MHz of repetition rate to generate broadened spectra dominated by SPM, which induces temporal variations of the ultrafast pulse intensity. The quasi-TE mode was coupled into the USRN waveguides via tapered lensed fiber. The spectra of output TE signals were observed through optical spectrum analyzer. We use two different structures of USRN waveguides (a bus waveguide with a single ring resonator and a short-length waveguide) to detect the characteristics of their spectral broadening and Q-factor using femtosecond pulses.

First, we investigate the output spectra from the pass ports of two USRN add-drop ring resonators (USRN_RR1 and USRN_RR2) waveguides as shown in Fig. 2. USRN_RR1 and USRN_RR2 possessing a 20 μm ring radius both were fabricated to have gaps of 150 nm and 100 nm gap between ring and bus waveguide, respectively. The length of the bus waveguide is 430 μm for USRN_RR1 and 650 μm for USRN_RR2.

The transmission spectra at each pass port are present with the number of resonant peaks as shown in Fig. 2(a). The spectral bandwidth of the input pulse entering the waveguides is measured to be approximately 60 nm at the −30 dB level. The bandwidth measured at the output of USRN_RR1 and RR2 was 110 nm and 130 nm respectively, representing 1.8 and 2.2 times broadening over the original pulse bandwidth. As expected, the output spectral width of USRN_RR2 is a larger because the longer bus waveguide length allows more nonlinear phase to be acquired (Qualitatively, the nonlinear phase acquired in the absence of any nonlinear losses, φNL = γ.Leff.Ppeak, where Leff is the effective waveguide length and Ppeak is the peak power used). Two spectral side wings in Fig. 2(a) appear with around 1530 and 1590 nm of center wavelengths. The wings depict an evidence of nonlinear broadening because these are situated outside the region where the fs source possesses spectral content. Consequently, the side wings due to nonlinear spectral broadening facilitate an increase in the number of observable resonance peaks. Each resonance peak is quantified by the Q-factor, defined as center wavelength divided by full-width half maximum (FWHM) bandwidth of a signal (See Fig. 2(b)). The free spectral range (FSR), defined as the spacing in optical frequency between two successive transmission peaks, of two USRN_RR are around 5 nm and the observable resonance peaks span a wavelength range from 1480 to 1640 nm. It is observed that the Q-factor is the highest at the shortest wavelength (USRN_RR1 = 15000 and USRN_RR2 = 11000), and decreases linearly as the wavelength is longer. A greater extent of the optical field is evanescent at longer wavelengths, and consequently, light stored/resonating within the ring couples more easily into the bus waveguide. In line with the definition of Q-factor (=energy stored / energy dissipated per cycle), it follows that Q-factor decreases at longer wavelengths.

Next, we investigate the nonlinear spectral broadening properties of a USRN waveguide (USRN_SWG) with 1.2 mm length (∼2× that in the ring resonator with the 650 μm bus waveguide). The output spectra of 500 fs pulses launched into USRN_SWG are observed as the input peak power (Ppeak) is increased and the results are shown in Fig. 3. The output spectrum is observed to broaden as the Ppeak is increased from 26 W to 66 W. Ppeak denoted in the figure depicts the coupled input peak power compensated for waveguide loss (10 dB/cm) and output fiber-waveguide coupling loss (∼10 dB per facet). The spectra corresponding with Ppeak = 26 W, 40 W and 53 W are observed to be highly symmetric, therefore SPM-induced broadening is likely to be the dominant effect. Soliton effects and Cherenkov radiation for example is unlikely to be present at these length scales – It often facilitates the broadening of pulse spectra in the regime of supercontinuum, through dispersive wave formation and consequently results in spectra which are asymmetric. At Ppeak = 66 W, the spectral envelope appears slightly asymmetric with different power levels between two wings located on either side of a 1.55-μm spectral peak. The LNL calculated for Ppeak = 66 W is ∼3.0 × 10−2 mm. The parameter N2 (=LD/LNL) is around 10000, in other words, N2 ≫ 1. Therefore, it shows that SPM dominates over group velocity dispersion (GVD) for spectral broadening27. If we don’t take into account dispersion effect due to dominantly large SPM effect, the asymmetric shapes can arise from the interplay of SPM and high order nonlinear effects. For ultrashort input pulses, self-steepening effect resulting from the intensity dependence of the group velocity occurs and it leads to an asymmetry in the SPM-broadened spectra28. Especially, self-steepening at the trailing edge of the pulse produces optical shock formation29. When loss is assumed to be zero for simplicity, the shock distance zs defined as ∼0.43LNL/s for hyperbolic secant pulse typical in a fiber laser (Where parameter s = 1/ω0T0, ω0 = angular frequency, T0 = TFWHM/1.76 for hyperbolic secant pulse, TFWHM = 500 fs)25. The shock distance, zs at Ppeak = 66W is around 4 mm at 1.55 μm, respectively. zs has same order of length with the waveguide length (=1.2 mm), so self-steepening -induced asymmetric spectral shape might account for the slight asymmetry in the spectrally broadened pulse (see Fig. 3). In addition, SPM-broadening can be limited by the extent of propagation loss that is related with Leff27. The experimentally measured loss coefficient αwg is 2.30 cm−1. Leff defined as (1 − exp(−αwgL))/αwg is calculated to be 0.10 cm at a physical length L = 1.2 mm. The maximum achievable Leff (Leff(max)) becomes 0.43 cm as L goes to infinity. The calculation shows that reducing the propagation loss to 1 dB/cm enables 10% increase in SPM-broadening parameter, φNL owing to the increase of Leff value for same waveguide length and experimental condition.

The spectral bandwidth at −30 dB level, Δλ30 dB, is also drawn as a function of input peak power in Fig. 4(a). The bandwidth increases linearly up to Ppeak ∼ 66 W with 2.3 nm/W of a slope. To investigate nonlinear loss including TPA effects on the USRN_SWG, output peak power (Pout) is measured as a function of Ppeak up to 100 W. Ppeak varies by using a digital variable attenuator and Pout is calculated from measured average output power at output tapered fiber via the USRN waveguide. Variation of the reciprocal transmission as the input peak power is varied (Ppeak/Pout versus Ppeak30) allows us to extrapolate the presence of two photon absorption. Ppeak/Pout is observed in Fig. 4(b) to be almost flat with a standard deviation of 0.78 and an average of 23, implying the absence of nonlinear loss at these power levels. Therefore, the linear increase in both the output bandwidth and power versus Ppeak indicates that USRN waveguide has relatively low nonlinear losses including TPA and free carrier effects up to Ppeak = 100 W. The spectral evolution of 500 fs pulses as a function of input peak power calculated using the Nonlinear Schrödinger equation is shown to increase linearly as Ppeak increases (see Fig. 4(c)). The calculation also reveals that the pulse spectrum spans from 1450–1700 nm at Ppeak ∼ 66 W, which corresponds well with the experimental result (See Fig. 3).

(a) Spectral bandwidths of 1.2 mm USRN_SWG at −30 dB level as a function of input peak power (b) Measured value of Ppeak/Pout vs. Ppeak. The flat profile obtained for Ppeak/Pout as Ppeak is varied implies negligible nonlinear losses. (c) Evolution of the 500 fs pulses as a function of the input peak power.

To see the effect of the spectral broadening on the waveguide length, we compared the output spectra as a function of waveguide length as shown in Fig. 5. Figure 5(a) shows measured spectra of 1.2-mm and 1.6-mm length USRN_SWG. Δλ30 dB of 1.2 and 1.6-mm USRN_SWG is around 230 and 270 nm, respectively which is 3.7 and 4.6 times larger than that of the fundamental input. The average measured output power was of 84 μW and 88 μW for 1.2-mm and 1.6-mm USRN_SWG, respectively. Δλ30 dB is also compared for USRN_RR1, USRN_RR2, USRN_SWG (1.2-mm-length) and USRN_SWG (1.6-mm-length). These 4 waveguides have different interaction lengths, so Δλ30 dB in terms of waveguide length can be plotted as shown in Fig. 5(b). If we adopt a linear fit into the graph, the slope is derived to around 150 nm/mm, implying that the bandwidth broadens by 150 nm per millimeter of USRN waveguide.

We define a length-dependent broadening factor, Fb (=Δλout /(Δλin · L), mm−1) which takes into account the bandwidth ratio between input (Δλin) and output pulses (Δλout) per unit length in the waveguide (L). For USRN waveguides with lengths of 1.2 mm and 1.6 mm, the Fb is 3.19 and 2.81 respectively. The comparison of Fb between our USRN_SWG with other platforms measured at the telecommunication bands is listed in Table 1. The table includes other reports on both SPM and SCG spectral broadening with a few to hundreds mm of waveguide length. SPM-broadening is normally implemented with hundreds and thousands femtoseconds of pulse widths. Fb is shown less than 0.1 excluding the silicon nitride waveguide (Fb ∼ 0.36)15 that is achieved due to relative short waveguide length. It indicates that the Fb value on our waveguide is more than 30 times larger than other SPM-broadened data even though the broadened spectra from our device is also dominated by SPM. Our USRN_SWGs have relatively the shortest length, but the highest Fb (∼3) among SPM-induced waveguides. This is because γ in our demonstrated USRN waveguides is ~ 550 W-1/m25 which is large enough to induce spectral broadening even with lengths as short as 1 mm. Comparing the reports on SCG broadening listed in Table 1, Fb is observed to be ≤1 except for that on ref. 42. We note further that in ref. 42, the longer length scales enable nonlinear effects in addition to pure self – phase modulation such as dispersive wave formation to help facilitate the spectral broadening. The Si3N4 waveguide (ref. 42) depicts higher Fb than other SCG-generated waveguides owing to engineering of two zero-GVD points and very small propagation losses (=0.7 dB/cm) for coherent SCG. Despite these benefits to obtain the broad SCG spectrum, however, Fb is ∼0.7 times smaller than those in our USRN-SWG. Furthermore, we only estimated the minimum (transform-limited) input spectral width at −30 dB level on the Si3N4 waveguide by time-bandwidth product assuming Sech2 pulse, so Fb value might in fact be smaller than what we expected. Frequency comb generation in a silicon nanophotonic wire waveguide reported in ref. 43 is characterized by an Fb ∼ 0.24 because of the broad input spectral width even with an octave spanning. Based on Table 1, therefore, our USRN_SWG achieves high spectra-broadened efficiency even with ultra-short lengths because of a combination of large nonlinearity and negligible nonlinear losses. In addition, high powers can be used without TPA effects. Such TPA effects have been widely documented to occur at sub – watt powers in silicon waveguides.

Using the USRN waveguides with a length of 1 mm, an output bandwidth of around 200 nm centered at 1550 nm is achieved.

Discussions

When we consider the third order dispersion (TOD), TOD length, defined as LD′ = T03/β3, is ∼0.3 m (β3 = 68 ps3/km at 1.555 μm)25. LD and LD′ are about 0.3 m–4 orders of magnitude larger magnitude than LNL and 300 times larger than the waveguide length in USRN_SWG (∼1 mm). Consequently, we don’t take into account dispersion effects in the broadened spectra. The asymmetric spectral shape as shown in Fig. 3 can be attributed to other nonlinear effects such as modulation instability as well as self-steepening effect because the waveguide’s anomalous dispersion could trigger several nonlinear processes for extending the spectra. The spectral shape around 1.55-μm-wavelength doesn’t show significant phase shift as input peak power increase, but instead, the spectrum broadens with high order sidebands as shown in Fig. 3. Therefore, it is difficult to identify the nonlinear effects present by solely observing output spectral shapes. Through observations of the broadened spectra, their evolution and the length scales involved, self – phase modulation is likely to be the dominant effect contributing to the spectral broadening.

Conclusions

We have studied ultrafast wideband broadening of USRN waveguides which are around 1 mm in length. USRN add-drop ring resonators broaden the output spectra by a factor of around 2 compared with the bandwidth of the 500 fs input pulses. The Q-factors, which range from 1480 and 1680 nm, measured at pass ports of the resonators are examined to have the highest values of 11000 and 15000 according to the bus waveguide length with a free spectral range of 5 nm. In addition, short waveguides of 1.2 mm and 1.6 mm USRN_SWG facilitated broadening of the spectral bandwidth to 230 and 270 nm, corresponding to 3.8 and 4.5 times larger than that of the fundamental input, respectively. Owing to the high nonlinear parameter (γ ∼ 550 W−1/m) and low TPA of USRN, the waveguides possess a higher Fb (∼3) than that in other CMOS-compatible platforms. Therefore, we can obtain output bandwidths of 200 nm (0.2 octaves) centered at 1.55 using ultra-short USRN waveguides with 1 mm in length. Consequently, the demonstrated USRN waveguides could be well poised to enable CMOS-compatible nonlinear optical devices with much smaller footprints due to its short length and high nonlinearity, and find applications in wideband and multi-wavelength generation at the telecommunications wavelength.

Methods

Measurements

A 500 fs fiber laser centered around 1.55 μm with 20 MHz repetition rate was used as a fundamental source. The laser polarization maintains with quasi TE mode, linearly horizontal-polarized by using in-line fiber polarization controller. The polarization-maintained input light was coupled into USRN waveguides via tapered lensed fiber. Output TE signals were also coupled into the same type of polarization maintaining tapered fiber and their spectra were observed through optical spectrum analyzer.

Device fabrication

Fabrication of the waveguides was performed by first depositing 300 nm of ultra – silicon rich nitride films using inductively coupled chemical vapor deposition. In order to minimize N – H bonds which are known to cause materials losses close to 1.55 μm, precursor gases used were SiH4 and N2. The gas flow ratio of SiH4:N2 used to deposit the films in this work was ∼2:1. The deposition temperature used was 250 °C. The waveguides were then defined using electron – beam lithography followed by reactive ion etching. Finally, 2 μm of SiO2 overcladding was deposited using plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Choi, J. W. et al. Wideband nonlinear spectral broadening in ultra-short ultra - silicon rich nitride waveguides. Sci. Rep. 6, 27120; doi: 10.1038/srep27120 (2016).

References

Leuthold, J., Koos, C. & Freude, W. Nonlinear silicon photonics. Nature Photon. 4, 535–544 (2010).

Hartl, I. et al. Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography using continuum generation in an air–silica microstructure optical fiber. Opt. Lett. 26, 608–610 (2001).

Diddams, S. A. et al. Direct link between microwave and optical frequencies with a 300 THz femtosecond laser comb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5102–5105 (2000).

Boyraz, O., Kim, J., Islam, M. N., Coppinger, F. & Jalali, B. 10 Gb/s Multiple wavelength, coherent short pulse source based on spectral carving of supercontinuum generated in fibers. J. Lightwave Technol. 18, 2167–2175 (2000).

Jalali, B. Nonlinear optics in the mid-infrared. Nature Photon. 4, 506–508 (2010).

Liang, T. K. & Tsang H. K. Nonlinear absorption and Raman scattering in silicon-on-insulator optical waveguides. IEEE J. Selected Topics in Quant. Electron. 10, 1149–1153 (2004).

Ta’eed, V. G. et al. Ultrafast all-optical chalcogenide glass photonic circuits. Opt. Express 15, 9205–9221 (2007).

Lamont, M. R. E., Luther-Davies, B., Choi, D. Y., Madden, S. & Eggleton, B. J. Supercontinuum generation in dispersion engineered highly nonlinear (γ = 10/W/m) As2S3 chalcogenide planar waveguide. Opt. Express 16, 14938–14944 (2008).

Eggleton, B. J., Luther-Davis, B. & Richardson, K. Chalcogenide photonics. Nature Photon. 5, 141–148 (2011).

Kang, S. et al. All-optical quantization scheme by slicing the supercontinuum in a chalcogenide horizontal slot waveguide. J. Opt. 17 085502 (2015).

Dolgaleva, K., Ng, W. C., Qian, L. & Aitchison, J. S. Compact highly-nonlinear AlGaAs waveguides for efficient wavelength conversion. Opt. Express 19, 12440–12455 (2011).

Lacava, C., Pusino, V., Minzioni, P., Sorel, M. & Cristiani, I. Nonlinear properties of AlGaAs waveguides in continuous wave operation regime. Opt. Express 22, 5291–5298 (2014).

Apiratikul, P. et al. Enhanced continuous-wave four-wave mixing efficiency in nonlinear AlGaAs waveguides. Opt. Express 22, 26814–26824 (2014).

Daldosso, N. et al. Comparison among various Si3N4 waveguide geometries grown within a CMOS fabrication pilot line. J. Lightwave Technol. 22, 1734–1740 (2004).

Tan, D. T. H., Ikeda, K., Sun, P. C. & Fainman Y. Group velocity dispersion and self phase modulation in silicon nitride waveguides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 061101 (2010).

Ikeda, K., Saperstein, R. E. & Alic, N. & Fainman Y. Thermal and Kerr nonlinear properties of plasma-deposited silicon nitride/silicon dioxide waveguides. Opt. Express 16, 12987–12994 (2008).

Levy, J. S. et al. CMOS-compatible multiple-wavelength oscillator for on-chip optical interconnects. Nature Photon. 4, 37–40 (2010).

Epping, J. P. et al. High confinement, high yield Si3N4 waveguides for nonlinear optical applications. Opt. Express 23, 642–648 (2015).

Monro, T. M. et al. Progress in microstructured optical fibers. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 36, 467–495 (2006).

Razzari, L. et al. CMOS-compatible integrated optical hyper-parametric oscillator. Nature Photon. 4, 41–45 (2010).

Okawachi, Y. et al. Octave-spanning frequency comb generation in a silicon nitride chip. Opt. Lett. 36, 3398–3400 (2011).

Levy, J. S. et al. High-performance silicon-nitride-based multiple-wavelength source. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 24, 1375–1377 (2012).

Barwicz, T. et al. Microring-resonator-based add-drop filters in SiN: fabrication and analysis. Opt. Express 12, 1437–1442 (2004).

Krückel, C. J. et al. Linear and nonlinear characterization of low-stress high-confinement silicon-rich nitride waveguides. Opt. Express 23, 25827–25837 (2015).

Wang, T. et al. Supercontinuum generation in bandgap engineered, back-end CMOS compatible silicon rich nitride waveguides. Laser Photon. Rev. 9, 498–506 (2015).

Ng, D. K. T. et al. Exploring high refractive index silicon-rich nitride films by low temperature inductively coupled plasma chemical vapor deposition and applications for integrated waveguides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 21884–21889 (2015).

Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear Fiber Optics (Academic, 1995).

Shimizu F. Frequency broadening in liquids by a short light pulse. Phys Rev. Lett. 19, 1097–1100 (1967).

DeMartini, F., Townes, C. H., Gustafson, T. K. & Kelley, P. L. Self-steepening of light pulses. Phys. Rev. 164, 312–323 (1967).

Tsang, H. K. et al. Optical dispersion, two-photon absorption and self-phase modulation in silicon waveguides at 1.5 μm wavelength. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 416–418 (2002).

Boyraz, O., Indukuri, T. & Jalali, B. Self-phase-modulation induced spectral broadening in silicon waveguides. Opt. Express, 12, 829–834 (2004).

Koonath, P., Solli, D. R. & Jalali, B. Continuum generation and carving on a silicon chip. App. Phys. Lett. 91, 061111 (2007).

Duchesne, D. et al. High Performance, low-loss nonlinear integrated glass waveguides PIERS ONLINE 6, 283–286 (2010).

Hsieh, I.-W. et al. Supercontinuum generation in silicon photonic wires Opt. Express 15, 15242–15249 (2007).

Yin, L., Lin, Q. & Agrawal G. P. Soliton fision and supercontinuum generation in silicon waveguides. Opt. Lett. 32, 391–393 (2007).

Safioui, J. et al. Supercontinuum generation in hydrogenated amorphous silicon waveguide. Nonlinear Optics, OSA Technical Digest (online), paper NM3A.7 (Optical Society of America, 2013).

Leo F. et al. Broadband, stable and highly coherent supercontinuum generation at telecommunication wavelengths in an hydrogenated amorphous silicon waveguide. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.5571 (2014).

Duchesne, D. et al. Supercontinuum generation in a high index doped silica glass spiral waveguide Opt. Express 18, 923–930 (2010).

Evans, C. C. et al. Spectral broadening in anatase titanium dioxide waveguides at telecommunication and near visible wavelengths. Opt. Express, 21, 18582–18591 (2013).

Epping, J. P. Dispersion Engineering Silicon Nitride Waveguides for Broadband Nonlinear Frequency Conversion. (Ph.D. thesis in University of Twente, 2015).

Halir, R. et al. Broadband supercontinuum generation in a CMOS-compatible platform. Opt. Lett. 37, 1685–1687 (2012).

Johnson, A. R. et al. Octave-spanning coherent supercontinuum generation in a silicon nitride waveguide. Opt. Lett. 40, 5117–5120 (2015).

Kuyken B. et al. An octave-spanning mid-infrared frequency comb generated in a silicon nanophotonic wire waveguide. Nat. Commun. 6, 6310 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the MOE ACRF Tier 2 grant, A*STAR PSF grant, SUTD – MIT International Design center and SUTD – ZJU collaborative research grant. The authors acknowledge the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under its Medium Sized Centre Program. This work is a collaboration project between SUTD and DSI (A*STAR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.C. performed experimental characterization. D.K.T.N., G.F.R.C. and D.T.H.T. performed materials and device fabrication. J.W.C. and K.J.A.O. performed simulations. J.W.C. and D.T.H.T. analyzed the experimental data. J.W.C. wrote the manuscript with contributions from D.T.H.T. All authors contributed to the manuscript. D.T.H.T. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, J., Chen, G., Ng, D. et al. Wideband nonlinear spectral broadening in ultra-short ultra - silicon rich nitride waveguides. Sci Rep 6, 27120 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27120

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27120

This article is cited by

-

Supercontinuum generation in a nonlinear ultra-silicon-rich nitride waveguide

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Enhanced photonics devices based on low temperature plasma-deposited dichlorosilane-based ultra-silicon-rich nitride (Si8N)

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Ge–Sb–S–Se–Te amorphous chalcogenide thin films towards on-chip nonlinear photonic devices

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Optical nonlinearities in ultra-silicon-rich nitride characterized using z-scan measurements

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Si-rich Silicon Nitride for Nonlinear Signal Processing Applications

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.