Abstract

Variation in the availability and distribution of food resources is a strong selective pressure on wild primates. We explored variation in Tibetan macaque gut microbiota composition during winter and spring seasons. Our results showed that gut microbial composition and diversity varied by season. In winter, the genus Succinivibrio, which promotes the digestion of cellulose and hemicellulose, was significantly increased. In spring, the abundance of the genus Prevotella, which is associated with digestion of carbohydrates and simple sugars, was significantly increased. PICRUSt analysis revealed that the predicted metagenomes related to the glycan biosynthesis and metabolic pathway was significantly increased in winter samples, which would aid in the digestion of glycan extracted from cellulose and hemicellulose. The predicted metagenomes related to carbohydrate and energy metabolic pathways were significantly increased in spring samples, which could facilitate a monkey’s recovery from acute energy loss experienced during winter. We propose that shifts in the composition and function of the gut microbiota provide a buffer against seasonal fluctuations in energy and nutrient intake, thus enabling these primates to adapt to variations in food supply and quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Survival and reproduction are dependent upon each individual’s ability to adjust to seasonal variation in food availability, abundance and distribution1. As one moves away from the equator, photosynthesis, plant growth and reproduction are increasingly affected by seasonal variation2. Animal patterns of nutrient intake change dramatically across seasons and habitats due to variation in temporal availability of food resources3. Understanding how wild animals solve these feeding challenges provides insight into the ecology and evolution of species4.

Non-human primates (NHPs) originated in tropical rainforest habitats and radiated into woodland, savanna and montane environments5. To adapt to temporal fluctuations in food resources while meeting nutritional requirements needed to sustain life, they have evolved anatomical and behavioral strategies, including specialized stomachs, habitat use patterns, ranging behavior and social organization6,7,8,9,10. Generally, NHPs prefer high-quality foods such as fruits and young leaves, which are rich in easily-digestible carbohydrates, lipids and proteins. However, these foods are not consistently available throughout the year5,9,11,12. For example, in winter, NHPs living in temperate environments eat a wide variety of low-quality foods13. Low-quality foods like mature leaves, gum and roots are often high in cellulose and dietary fiber which are difficult to digest14,15. Previous studies have found that primates shift their activity budgets and foraging patterns in response to ecological pressures imposed during periods of food scarcity9,16,17,18. How wild primates digest and metabolize low-quality foods during periods of limited food resource availability has been overlooked3.

The mammalian digestive system is home to a complex microbial community, many of which have symbiotic relationships with particular hosts19,20,21,22. Studies of humans and laboratory animals have demonstrated that the changes in host diet and physiology can alter gut microbiome composition20,23,24,25. Additionally, it has been found that gut microbial communities have mutualistic relationships with host by impacting the host’s ability to digest and assimilate food, thus providing the host with energy and nutrients24. For example, gut microbes can help a host break down otherwise indigestible materials such as cellulose and hemicellulose, thereby using these compounds to meet physiological needs26. Changes in gut microbiome composition are therefore generally considered to be microbial responses to selective pressures imposed by changes in the host’s diet, health and physiology21,22. These microbial shifts allow the host to digest food items more efficiently to meet energy and nutrient demands3,27. Mutualistic host/microbe relationships likely vary seasonally in response to temporal alterations in food resources3 and this response is expected to be particularly apparent at sites with distinct seasonal variation in the occurrence of high- and low-quality foods. However, few data are currently available to explore this relationship in wild primates.

Our study population of free-ranging Tibetan macaques (Macaca thibetana) is ideal to explore seasonal variation in gut microbiota. The members of our study group (Yulinkeng A1 or YA1) have been observed for nearly 30 years. All adult group members can be identified by distinctive physical features (i.e. scars, hair color patterns and/or facial/body appearance) and the ages and matrilineal relationships of all YA1 monkeys are known. Male immigrants’ ages are estimated from comparisons to males of known ages and their identities are thereafter monitored by their distinctive physical features (i.e. missing canines, scars, missing hands/feet)28. The troop inhabits deciduous and evergreen broad-leaf mixed montane forests. Previous studies indicated that in general the Tibetan macaque diet consists of leaves, fruits, grass and to a lesser extent, flowers, roots and insects29,30. The site has an annual average temperature of 15.3 °C (highest: 34.2 °C, lowest: −13. 9 °C). Winter temperatures drop below 0 °C. Most winters, the temperature can remain below freezing for more than 40 consecutive days29.

We used high-throughput sequencing methods to compare gut microbiota variation between seasons of low- and high-quality food consumption in our study group. From winter to spring, monkeys in the study group experience a seasonal shift in food quality. Temperature and rainfall, which are comparatively homogeneous within seasons, vary more markedly between seasons29 thereby affecting food availability. Mature leaves, roots and other fibrous foods with high proportions of cellulose increase in the Tibetan macaques’ winter diet, while the amount of dietary pectin and simple sugars in the diet increases in the spring as monkeys shift their diet to include more young leaves7,29,30,31. Based on this seasonal dietary shift, we tested two hypotheses:

-

1

H1: Gut microbiome diversity, as measured by alpha and beta diversity, differs significantly in winter and spring.

-

2

H2: The relative abundance of gut microbiome genera that aid in digestion of cellulose and fiber is higher in winter compared to spring and the relative abundance of genera that aid in digestion of pectin and simple sugars is higher in spring compared to winter.

Results

Microbial community profiles

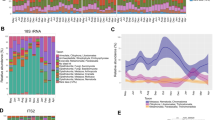

After quality filtering, we acquired 572,564 high-quality filtered reads, corresponding to 11,928 ± 2930 reads per monkey from a total of 48 fecal samples. Taxonomic assignment revealed representatives from 14 known bacterial phyla at 97% sequence identity across winter and spring seasons (Fig. 1). Similar to other mammals, Tibetan macaque gut microbiota was largely dominated by Firmicutes (x = 43.43 ± 8.51%), Bacteriodetes (x = 35.20 ± 6.39%) and Proteobacteria (x = 14.67 ± 8.78%). Other represented phyla were Spirochaetes (x = 2.03 ± 2.25%), Actinobacteria (x = 0.48 ± 0.62%) and Verrucomicrobia (x = 0.10 ± 0.079%) (Supplementary Table S2). The predominant genera of bacteria isolated from the monkeys’ fecal samples were Prevotella (x = 17.82 ± 0.0867%) and Succinivibrio (x = 10.84 ± 0.869%). To evaluate gut microbial diversity, we estimated of diversity within (alpha) gut microbial communities using Shannon diversity index of diversity (H = 4.84 ± 0.39), Simpson’s diversity index (D = 0.038 ± 0.0235), OTU richness (x = 1241 ± 409), Chao 1 (x = 5620 ± 3425) and ACE (x = 3288 ± 1550) (Supplementary Table S1).

Variation of gut microbiome in winter and spring

To explore gut microbial community differences between seasons and the potential influence of a monkey’s sex and age, alpha diversity including Shannon diversity index, OTU richness, Chao 1 and ACE was estimated with linear mixed models. We found no evidence for significant influence of season or monkey’s sex and age using OTU richness, Chao, ACE (P > 0.1) and Simpson’s diversity index (P = 0.065). However, Shannon diversity index had a significant seasonal difference, whereby species diversity significantly increased in spring samples (Estimate = 0.222, Std. Error = 0.106, df = 31.5, t = 2.09, P = 0.045) compared to winter samples.

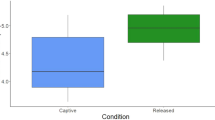

The distribution of beta diversity measures (weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances) was compared between different seasons (winter–winter dyads, WW, N = 210; spring–spring dyads, SS, N = 351 and winter–spring dyads, WS, N = 567). PCoA was used to show patterns of separation by seasons. Permanova tests between WW and SS revealed a significant seasonal separation based on unweighted UniFrac distances (Permanova tests, F = 2.98, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2a) and weighted UniFrac distances (Permanova tests, F = 3.65, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2b). However, we did not find a significant influence (Permanova tests, P > 0.05) of monkeys’ age or sex on UniFrac distances (weighted and unweighted). According to Costello, E. K. et al.32, we used the UniFrac distances to estimate inter-individual differences within each season. To detect the differences of UniFrac distances (weighted and unweighted) within each season’s samples, we performed permutation tests (permutations = 999) by permuting the W and S labels across individuals and generating a null distribution of mean difference in beta-diversity across the two seasons. A significantly higher dissimilarity was found within winter samples than was found within spring samples (weighted: WW vs SS, P < 0.001; unweighted: WW vs SS, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c,d).

Gut microbiota structure differentiation and inter-individual similarity.

PCoA was used to show patterns of separation by season, Yellow: spring sample; green, winter sample; (a) based on unweighted UniFrac distance (Permanova, P < 0.05), (b) based on weighted UniFrac distance (Permanova, P < 0.01). Permutation test was used to test inter-individual similarity; Yellow box (winter vs winter, WW); green box (spring vs spring, SS); (c) based on unweighted UniFrac distance (WW vs SS, permutations = 999, P < 0.001); (d) based on weighted UniFrac distance (WW vs SS, permutations = 999, P < 0.0001).

To explore the variation of the microbial community composition between the two seasons’ samples, we performed LEfSe tests to detect differences in relative abundance (average relative abundance >0. 01%) of bacterial taxa (including phylum and genus) across samples (Supplementary S2, S3). At phyla levels, our LEfSe analysis revealed that the phyla Proteobacteria and Spirochaetia were significantly enriched in winter samples, while the phylum Firmicutes was significantly enriched in spring samples (LDA > 2, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3a). At the genus level, four known genera (Succinivibrio, Treponema, Clostridium sensu stricto and Alloprevotella) were significantly enriched in winter samples and sixteen genera (Prevotella, Blautia, Gemmiger, Barnesiella, Lachnospiracea incertae sedis, ClostridiumXlVb, Anaerostipes, Catenibacterium, Flavonifractor, Coprococcus, Butyricicoccus, Roseburia, Clostridium IV, Dorea Erysipelotrichaceae incertae sedis and Faecalibacterium) were significantly enriched in spring samples (LDA > 2, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3b).

Phylum and genus differentially represented between winter and spring samples identified by linear discriminant analysis coupled with effect size (LEfSe) (LDA > 2, P < 0.05).

Red box: enriched in spring samples, green box: enriched in winter samples. (a) based on the relative abundance of phylum; (b) based on the relative abundance of genus.

Variation of predicted metagenomes between winter and spring

Using PICRUSt as a predictive exploratory tool, 39 level 2 KEGG Orthology groups (KOs) were represented in the data set (Fig. 4). The mean weighted nearest sequenced taxon index (NSTI) for our samples was 0.142 ± 0.027. This result is similar with previously reported analyses in mammals (mean NSTI = 0.14 ± 0.06)33. Despite the accuracy of predictions being lower in mammals than for humans (mean NSTI = 0.03 ± 0.02), it can still provide useful information of functional predictions for mammalian microbiomes33. To explore the variation of predicted metagenomes in winter and spring, we performed LEfSe tests to detect KEGG pathways with significantly different abundances between winter and spring samples. We found that seven KEGG pathways (Cell motility, Glycan Biosynthesis and Metabolism, Signal Transduction, Amino Acid Metabolism, Transport and Catabolism, Endocrine System and Neurodegenerative Diseases) were significantly enriched in winter samples and six KEGG pathways (Transcription, Enzyme Families, Energy Metabolism, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Cellular Processes and Signaling and Metabolism of Cofactors and Vitamins) were significantly increased in spring samples (LDA > 2, P < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Relative abundance of the predicted gene of metagenome related to KEGG pathways at level 1 and 2; orange box: winter samples, green box: spring samples.

The terms given on the left are KEGG pathways annotation at level 1 and level 2 (from left to right). **Enriched in winter samples (LDA > 2, P < 0.05); *enriched in spring samples (LDA > 2, P < 0.05).

Discussion

Wild NHPs have successfully radiated into various seasonal habitats5. Anatomical and behavioral strategies are generally considered as the primary ways NHPs adapt to temporal fluctuations of food resources9,16,17,18. Having a diverse and responsive gut microbial community may be another important adaptive mechanism. The gut microbial community composition and diversity in our study group strongly shifted between the two seasons. This finding supports H1 that gut microbiome diversity will be significantly different in the two seasons. In highly seasonal ecosystems such as Mt. Huangshan, NHPs are exposed to variable temperatures and rainfall and undergo corresponding seasonal shifts in home range use and food resources. Previous studies show that these factors can affect gut microbiome composition3,34,35. From winter to spring, monkeys in our study group experience a seasonal shift in food type and quality, temperature and rainfall29. These environmental factors are comparatively homogeneous within seasons but vary more markedly between seasons29,30, resulting in marked variation of gut microbiota between winter and spring in this population. We found that the differences of inter-individual gut community structure were significantly higher in winter, which revealed that inter-individual gut community structure was more different among individuals in winter and more similar in spring. A possible explanation for this finding is that more intense feeding competition exists among individuals during winter (a period of food scarcity), which results in greater individual differences in resource acquisition. With the increase of food availability in spring, the dietary intake of individuals converges on a more similar pattern as feeding competition declines.

What are the potential consequences of the observed seasonal shifts in the wild Tibetan macaque gut microbial community structure? It is widely accepted that a change of gut microbial composition may allow hosts to digest food more efficiently to meet their energy and nutrient demands21,22,24,27,35. In highly seasonal ecosystems, NHPs are expected to undergo acute energy loss as they adapt to winter weather36. A diverse and responsive gut microbial community may be key to the adaptation process for NHPs living in extreme climates. At the phylum level, our study revealed that the relative abundances of Proteobacteria in the monkeys’ gut are significantly higher in winter than in spring. Previous studies in humans, mice and black howler monkeys have demonstrated that Proteobacteria are mainly associated with energy accumulation21,22,35,37. Our results indicate that the increase in this phylum during the winter period may help Tibetan macaques cope with cold weather. Recent controlled experiments in mice showed that cold exposure significantly increased the phylum Proteobacteria and this change helped the host to withstand periods of high energy demand typical during cold periods35. We did not detect a significant increase of predicted genes from the metagenome related to energy metabolism pathways in samples collected from our study monkeys during the winter. A possible explanation for this finding is that the food quality of our study group is different from the mice’s diet. From winter to spring, the food resources of Tibetan macaques change from low- to high-quality29,30. The higher proportion of predicted genes from the metagenome related to energy metabolic pathways might meet the monkeys’ energy metabolism needs in spring.

In addition to cold weather, our study population experiences changes in food quality across seasons. This is problematic for Tibetan macaques during the winter with respect to metabolizing cellulose and dietary fibers found in mature leaves, roots and other vegetative parts that they rely upon at that time of year. A comparison of our winter and spring results show that the most abundant microbiome genus, Succinivibrio, significantly increased in winter samples. Species belonging to Succinivibrio enrich rumen microbial ecosystems and are efficient in fermenting glucose through the production of acetic and succinic acids38, as well as in aiding in the metabolization of different types of fatty acids39, which may increase energy utilization efficiency for monkeys during winter.

The genus Clostridium contains organisms known to digest cellulose and hemicellulose40 and includes many genes that code for cellulose and hemicellulose-digestive enzymes found in the giant panda gut microbiome41. The significant increase of Clostridium sensu stricto detected in the Tibetan macaque gut microbiome in winter suggests its potential utility for digesting cellulose and dietary fiber. Our PICRUSt analysis also revealed that predicted genes from the metagenome related to glycan biosynthesis and metabolic pathways are significantly increased in winter samples. This pathway is also present at high levels in the wild panda’s gut microbiome41 and is beneficial in digesting glycan produced by the breakdown of cellulose and hemicellulose. Thus, we propose that the pattern of gut microbiota found in Tibetan macaques during the winter may increase energy-efficient metabolism of winter foods. In spring, the abundance of the genus Prevotella significantly increased. During this time, our study monkeys increase their ingestion of young leaves, which are richer in more easily digestible energy and protein than mature leaves, roots and other vegetative parts29,30. Species in the genus Prevotella are associated with digestion of hemicellulose, pectin, carbohydrate and simple sugars, such as those found in fruits, cereals and young leaves3,42. The predicted genes from the metagenome related to the Carbohydrate Metabolism and Energy Metabolism pathways were also significantly increased in our spring samples. These results indicate that the changes measured in the gut microbial community in spring may be beneficial for a rapid recovery from acute energy and nutrition loss experienced during the cold winter months.

A recent human intervention study showed that rapid and reproducible changes in microbial community structure and function occur with the consumption of an animal-based versus a plant-based diet43. Similar evidence has also been found in wild mice and black howler monkeys3,34,44. These results, considered together with our current findings from wild Tibetan macaques, lead us to speculate that the symbiotic relationship between mammals and their gut microbiota may be an adaptive mechanism for solving dietary dilemmas imposed by seasonal fluctuations in food availability. Further research is necessary to test this hypothesis in more mammals, as well as to better understand the trade-off between nutrition and health via shifts in gut microbiota composition.

Material and Methods

Sample collection and Ethics statement

Because the monkeys in our study group are habituated, it is possible to follow them and collect fresh fecal samples. A total of 48 fecal samples were obtained from 33 identified individuals, representing 89.2% of the study group. Among them, 21 different individuals’ feces were sampled over two discrete periods in winter (Jan. 1 to 18, 2015) and 27 individuals in spring (March 24 to April 21, 2015). Sample and individual information are listed in the Supplementary Table S1. All fecal samples were collected, stored and shipped in RNAlater (QIA-GEN, Valencia CA). Samples were shipped at ambient temperatures but subsequently stored at −80 °C. All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Anhui Zoological Society (permit number BH20131202). All experiments were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations.

DNA extraction and sequencing

Frozen fecal samples were thawed on ice and dissected. To avoid soil contamination, DNA was then extracted from the inner part of the fecal samples. Total DNA was extracted from frozen stool samples using the QIAampt DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol for pathogen detection, with a modified protocol of the bead-beating procedure described by Schnorr et al.45. Total DNA extracted from 48 frozen stool samples was sent to the Genome Sequencing of Human Genome Research Centre, Shanghai, China, to carry out sequencing. The V3-V4 regions of 16S rDNA were individually purified with a Min Elute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and then quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit (Invitrogen, American). After the individual quantification step, amplicons were pooled in equal amounts and pair-end 2 × 200 bp sequencing was performed using the Illlumina Miseq platform and Miseq Reagent Kit v3.

Sequence analysis

Quality filtering and processing of sequences was performed in QIIME v1.7. The sequences containing the ambiguous base (N) were removed using in-house perl scripts and only those sequences with an average quality score >25 were included in the analysis. Mothur46 was used to determine OTUs and calculate rarefaction curves, rank-abundance plots, Chao1 richness estimates and Shannon diversity estimates according to MiSeq SOP (http://www.mothur.org/wiki/MiSeq_SOP). Sequences were clustered into 97% OTUs through a mothur-formatted version of the RDP training set (v.9) and assigned to respective taxonomic levels (phylum, class, order, family and genus).

Data analysis

Beta diversity (between sample diversity) was estimated by computing from the phylogenetic tree the unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances47 between samples. Weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances of genus-level relative abundance were used to perform PCoA using the packages Made4 and Vegan (http://www.cran.r-project.org/package=vegan). Multivariate analysis (Permanova test) was used to detect the influence of age, sex and season on beta diversity (unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances) variation and a Permanova test was performed in the vegan package of R with the function of GUniFrac48. Following Maurice, et al.44, we used linear mixed models to detect the potential multiple influences of season, age and sex on alpha diversity. Each individual’s ID was controlled as a random intercept term. Model assumptions were checked by examining the distribution of residuals and plotting fitted values against residuals; the response variable was log-transformed or square root where needed to meet the model assumptions. The same sets of predictors (age, sex and season) were included in all starting models. To detect bacterial taxa (including phylum and genus) and KEGG pathways with significantly different abundances between winter and spring samples, LEfSe analysis was used according to the online protocol (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu /galaxy/).

To explore the functional profiles of our bacterial community data set, the functional profiles of microbial communities were predicted using PICRUSt33 (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States) according to the online protocol (http://picrust.github.io/picrust/). For the analysis, OTUs were derived from the 16S rRNA gene present in the Greengenes database.

Additional Information

Accession codes: The raw sequences of this study have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (accession number SRP073002) http://www.nature.com/srep.

How to cite this article: Sun, B. et al. Marked variation between winter and spring gut microbiota in free-ranging Tibetan Macaques (Macaca thibetana). Sci. Rep. 6, 26035; doi: 10.1038/srep26035 (2016).

References

And, C. C. S. & Reichman, O. J. The Evolution of Food Caching by Birds and Mammals. Annu Rev Ecol 15, 329–351 (2003).

Endler, J. A. The Color of Light in Forests and Its Implications. Ecol Monogr 63, 1–27 (1993).

Amato, K. R. et al. The Gut Microbiota Appears to Compensate for Seasonal Diet Variation in the Wild Black Howler Monkey (Alouatta pigra). Microb Ecol 69, 434–443 (2014).

Emmons, L. H. Comparative feeding ecology of felids in a neotropical rainforest. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 20, 271–283 (1987).

Hanya, G. et al. Dietary adaptations of temperate primates: comparisons of Japanese and Barbary macaques. Primates 52, 187–198 (2011).

Milton, K. & May, M. L. Body weight, diet and home range area in primates. Nature 259, 459–462 (1976).

Chivers, D. & Hladik, C. M. In Food Acquisition and Processing in Primates (eds Chivers, DavidJ, Wood, BernardA & Bilsborough, Alan ) Ch. 9, 213–230 (Springer US, 1984).

Cachel, S. Primate adaptation and evolution. Int J Primatol 10, 487–490 (1989).

Hanya, G. & Chapman, C. A. Linking feeding ecology and population abundance: a review of food resource limitation on primates. Ecol Res 28, 183–190 (2013).

Yamada, A. & Muroyama, Y. Effects of vegetation type on habitat use by crop-raiding Japanese macaques during a food-scarce season. Primates 51, 159–166 (2010).

Shea, B. T., Rodman, P. S. & Cant, J. G. H. Adaptations for Foraging in Nonhuman Primates. Bioscience 35, doi: 10.2307/1309849 (1985).

Ungar, P. S. Fruit preferences of four sympatric primate species at Ketambe, northern Sumatra, Indonesia. Int J Primatol 16, 221–245 (1995).

Fan, P., Ni, Q., Sun, G., Bei, H. & Jiang, X. Gibbons under seasonal stress: the diet of the black crested gibbon (Nomascus concolor) on Mt. Wuliang, Central Yunnan, China. Primates 50, 37–44 (2009).

Coley, P. D. Herbivory and defensive characteristics of tree species in a lowland tropical forest. Ecol Monogr 53, 209–233 (1983).

Joly-Radko, M. & Zimmermann, E. in The Evolution of Exudativory in Primates (eds Anne Burrows, M. & Leanne Nash, T. ) 141–153 (Springer New York, 2010).

Zhou, Q. et al. Seasonal Variation in the Activity Patterns and Time Budgets of Trachypithecus francoisi in the Nonggang Nature Reserve, China. Int J Primatol 28, 657–671 (2007).

Starr, C., Nekaris, K. A. I. & Leung, L. Hiding from the Moonlight: Luminosity and Temperature Affect Activity of Asian Nocturnal Primates in a Highly Seasonal Forest. Plos One 7, e36396.36391–e36396.36398 (2012).

Campera, M. et al. Effects of Habitat Quality and Seasonality on Ranging Patterns of Collared Brown Lemur (Eulemur collaris) in Littoral Forest Fragments. Int J Primatol 35, 957–975 (2014).

Ley, R. E. et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 320, 1647–1651 (2008).

Hooper, L. V., Littman, D. R. & Macpherson, A. J. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336, 1268–1273 (2012).

Koren, O. et al. Host Remodeling of the Gut Microbiome and Metabolic Changes during Pregnancy. Cell 150, 470–480 (2012).

Amato, K. R. et al. The role of gut microbes in satisfying the nutritional demands of adult and juvenile wild, black howler monkeys (Alouatta pigra). Am J Phys Anthropol 155, 652–664 (2014).

Duncan, S. H. et al. Effects of alternative dietary substrates on competition between human colonic bacteria in an anaerobic fermentor system. Appl Environ Microbiol 69, 1136–1142 (2003).

Hooper, L. V., Midtvedt, T. & Gordon, J. I. How host-microbial interactions shape the nutrient environment of the mammalian intestine. Annu Rev Nutr 22, 283–307 (2002).

Davenport, E. R. et al. Seasonal variation in human gut microbiome composition. Plos One 9, e90731 (2014).

Mackie, R. I. Mutualistic Fermentative Digestion in the Gastrointestinal Tract: Diversity and Evolution. Integr Comp Biol 42, 1112–1112 (2002).

Donohoe, D. R. et al. The Microbiome and Butyrate Regulate Energy Metabolism and Autophagy in the Mammalian Colon. Cell Metab 13, 517–526 (2011).

Zhang, M. et al. Male mate choice in Tibetan macaques (Macaca thibetana) at Mt. Huangshan, China. Curr Zoo 56, 213–221 (2010).

Xiong, C. & Wang, Q. Seasonal habitat used by Thibetan Monkeys. Acta Theriol Sin 8, 176–183 (1988).

Zhao, Q. K. Responses to seasonal changes in nutrient quality and patchiness of food in a multigroup community of Tibetan macaques at Mt. Emei. Int J Primatol 20, 511–524 (1999).

Matsuda, I., Tuuga, A., Bernard, H., Sugau, J. & Hanya, G. Leaf selection by two Bornean colobine monkeys in relation to plant chemistry and abundance. Sci Rep-UK 3, 1873–1873 (2013).

Costello, E. K. et al. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326, 1694–1697 (2009).

Langille, M. G. I. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nature Biotechnol 31, 814–821 (2013).

Amato, K. R. et al. Habitat degradation impacts black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) gastrointestinal microbiomes. Isme J 7, 1344–1353 (2013).

Chevalier, C. et al. Gut Microbiota Orchestrates Energy Homeostasis during Cold. Cell 163, 1360–1374 (2015).

Tsuji, Y., Hanya, G. & Grueter, C. C. Feeding strategies of primates in temperate and alpine forests: comparison of Asian macaques and colobines. Primates 54, 201–215 (2013).

Bryant, M. P. & Small, N. J. Characteristics of two new genera of anaerobic curved rods isolated from the rumen of cattle. J Bacteriol 72, 22–26 (1956).

de Menezes, A. B. et al. Microbiome analysis of dairy cows fed pasture or total mixed ration diets. Fems Microbiol Ecol 78, 256–265 (2011).

Van Dyke, M. & McCarthy, A. Molecular biological detection and characterization of Clostridium populations in municipal landfill sites. Appl Environ Microbiol 68, 2049–2053 (2002).

Dyke, M. I., Van & Mccarthy, A. J. Molecular biological detection and characterization of Clostridium populations in municipal landfill sites. Appl Environ Microbiol 68, 2049–2053 (2002).

Zhu, L., Wu, Q., Dai, J., Zhang, S. & Wei, F. Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. P Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 17714–17719 (2011).

Wu, G. D. et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334, 105–108 (2011).

David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014).

Maurice, C. F. et al. Marked seasonal variation in the wild mouse gut microbiota. ISME J, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.53 (2015).

Schnorr, S. L. et al. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat Commun 5, doi: 10.1038/ncomms4654 (2014).

Kozich, J. J., Westcott, S. L., Baxter, N. T., Highlander, S. K. & Schloss, P. D. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol 79, 5112–5120 (2013).

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K. & Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220–230, doi: 10.1038/nature11550 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. Associating microbiome composition with environmental covariates using generalized UniFrac distances. Bioinformatics 28, 2106–2113 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31400330, 31172106), The Key Members of Teacher Development Program of Anhui University (No. 02303301), The Special Foundation for Excellent Young Talents in University of Anhui Province, China (No. 2012SQRL018ZD) and Youth Fund of Anhui University (No. 02303301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: B.S. and J.L. Performed the experiments: B.S., X.W., S.B., Z.G. and R.C. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: B.S., J.L., X.W., D.X. and R.W. Wrote the paper: B.S., J.L., M.A.H., L.S., R.W. and S.B. All authors reviewed the manuscript. B.S. and X.W. have same contribution.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, B., Wang, X., Bernstein, S. et al. Marked variation between winter and spring gut microbiota in free-ranging Tibetan Macaques (Macaca thibetana). Sci Rep 6, 26035 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26035

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26035

This article is cited by

-

Gut microbiota variations in wild yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) are associated with sex and habitat disturbance

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Seasonal Effects on the Fecal Microbial Composition of Wild Greater Thick-Tailed Galagos (Otolemur crassicaudatus)

International Journal of Primatology (2023)

-

Exploring variation in the fecal microbial communities of Kasaragod Dwarf and Holstein crossbred cattle

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (2023)

-

Comparative analysis of gut microbiota in healthy and diarrheic yaks

Microbial Cell Factories (2022)

-

The associations between intestinal bacteria of Eospalax cansus and soil bacteria of its habitat

BMC Veterinary Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.