Abstract

Although extensive research on neural plasticity resulting from hearing deprivation has been conducted, the direct influence of compromised audition on the auditory cortex and the potential impact of long durations of incomplete sensory stimulation on the adult cortex are still not fully understood. In this study, using voxel-based morphometry, we evaluated gray matter (GM) volume changes that may be associated with reduced hearing ability and the duration of hearing impairment in 42 unilateral hearing loss (UHL) patients with acoustic neuromas compared to 24 normal controls. We found significant GM volume increases in the somatosensory and motor systems and GM volume decreases in the auditory (i.e., Heschl’s gyrus) and visual systems (i.e., the calcarine cortex) in UHL patients. The GM volume decreases in the primary auditory cortex (i.e., superior temporal gyrus and Heschl’s gyrus) correlated with reduced hearing ability. Meanwhile, the GM volume decreases in structures involving high-level cognitive control functions (i.e., dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex) correlated positively with hearing loss duration. Our findings demonstrated that the severity and duration of UHL may contribute to the dissociated morphology of auditory and high-level neural structures, providing insight into the brain’s plasticity related to chronic, persistent partial sensory loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensory perception modulates the adaptation of cortical structures to various sensory experiences1,2. In previous studies, experience-dependent functional brain plasticity in the primary auditory cortex has been documented in deaf individuals3,4,5, and structural alterations in the deaf have also been found outside the auditory areas6,7. These findings support the hypothesis that auditory comprehension relies on a distributed network that includes not only the auditory cortex, such as the bilateral superior and middle temporal gyri, but also other “non-auditory” areas, such as the left prefrontal and premotor cortices8. In fact, auditory input is critical for cognitive processing to dynamically interact with the environment. A complex combination of perceptual and high-level cognitive factors builds the foundation for integrated auditory processing in individuals with normal hearing9,10. Accordingly, over time, reduced clarity of peripheral hearing, especially chronic and persistent reductions, may alter the auditory cortex and cause more extensive structural reorganization beyond auditory cortical regions. Although neural plasticity resulting from hearing deprivation has been studied intensively, there is little data on changes in both intra- and extra-auditory cortical structures and their correlations with hearing ability and hearing damage duration in hearing-damaged individuals11.

Unlike the congenitally deaf, most individuals with unilateral hearing loss (UHL) suffer from post-lingual hearing damage and have passed the critical period for cortical development. Therefore, any influence on the brain might induce traumatic changes in cortical morphology because of defective compensation. In particular, the ability to capture auditory information is largely preserved in UHL, but changes in auditory perception for further cognitive processing are more complicated11,12. UHL may affect integral auditory perception and auditory processing for higher-order representations13. As a result, various cortices for basic perception and high-level cognition may be subject to a wide range of plastic reorganization. The study of UHL offers a unique opportunity to explore cortical reorganization in response to auditory damage and its consequent relevance to severity and duration. Studying UHL also allows us to examine the direct influence of reduced hearing ability on cortical regions for sensory processing, as well as the consequences of prolonged partial deafness and its potential impact on high-level functions that lead to abnormal communication strategies.

This study used volumetric MRI with voxel-based morphometry (VBM)14,15,16 to examine the volumetric change and reorganization of cortical structures in UHL to gain insight into the impact of UHL severity and duration on neuroanatomical characteristics. In this study, UHL primarily resulted from unilateral acoustic neuroma (AN). Progressive unilateral sensorineural hearing damage is the most frequent initial symptom of AN, and it occurs in more than 90% of AN patients17. However, there was no other significant change in the quality of life during the observation period18, and preoperative AN offers a unique opportunity to explore the brain plasticity in UHL. We hypothesized that hearing ability and UHL duration would be associated with distinctive degenerations in gross cortical morphology, which may reflect the perceptual input damage and the interaction between perceptual and other cognitive factors.

Results

Demographics and measures of auditory characteristics

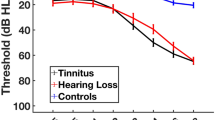

Table 1 shows the demographics and measures of auditory characteristics of the participants. There were no significant differences in age, gender, education and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) results between the normal controls (NCs) and left and right UHL patient groups (p values > 0.06). Most UHL participants had significant hearing damage in the impaired ear (14 left UHL with pure tone audiometry (PTA) ≥ 50 dB and 7 with 50 > PTA ≥ 20 dB; 16 right UHL with PTA ≥ 50 dB and the other 5 with 50 > PTA ≥ 20 dB). UHL patients showed higher PTA values in the impaired ear than the same-side ear in NCs (left UHL: t = 6.37, p < 0.001; right UHL, t = 7.85, p < 0.001). However, no significant difference was found between PTA values of unaffected ears in UHL patients and the same-side ears in NCs (t = 1.84, p = 0.07 for left UHL; t = 1.85, p = 0.07 for right UHL). There were no significant differences in the duration of hearing damage between left UHL (29.7 ± 10.7 ms) and right UHL (23.4 ± 11.4 ms) (t = 0.79, p = 0.43). PTA values showed no significant differences between the two patient groups between compromised ears (t = 0.23, p = 0.82) and contralateral ears with intact hearing (t = −0.12, p = 0.91). Table 2 shows that UHL participants had significantly higher hearing thresholds for bilateral ears under quiet conditions, and there was no differences between the two UHL groups (t = −0.422, p = 0.676). There were no significant differences in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) between compromised ears of left UHL (30.9 ± 23.2 dB S/N)) and right UHL patients (38.9 ± 24.6 dB S/N)) (t = −0.596, p = 0.556).

Volumetric differences between patients and normal controls

Significantly increased AN tumor volume was observed in left and right UHL patients compared to normal controls (Fig. 1). We observed increases in the GM volume of the left supplementary motor area, bilateral precentral gyrus and bilateral postcentral gyrus in UHL patients compared to the cortex of normal controls. In contrast, the GM volume of the bilateral superior temporal gyrus, bilateral middle temporal gyrus, bilateral inferior temporal gyrus, right Heschl’s gyrus, left hippocampus, and right calcarine cortex was decreased (Table 3, Fig. 2). These results indicate that reduced hearing ability in UHL directly influences regions related to auditory processing.

Volumetric differences between left and right UHL

The GM volume of the right perirhinal cortex in left UHL patients was greater than in right UHL patients (Table 4, Fig. 3). Meanwhile, the GM volume of the left superior temporal gyrus and right supplementary motor area was smaller than in right UHL patients. The most obviously reorganized regions were generally symmetrical, with few differences (i.e., the GM volume in the right supplementary motor area and left superior temporal gyrus in left UHL patients was smaller than in right UHL patients) in GM volumes between left and right UHL. These results demonstrate that UHL is associated with contralateral volume decrease in perirhinal cortex generally; in other words, the GM volume of the perirhinal cortex is specific to the laterality of UHL.

Correlations between hearing level and gray matter volume

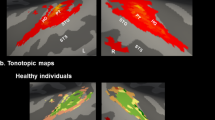

Regression analyses with hearing ability (PTA values, a large value indicates low hearing ability) as the independent variable and GM volume as the dependent variable showed that PTA values (equal to hearing threshold level) were positively correlated with the GM volume of the right superior frontal gyrus and left fusiform gyrus (Table 5, Fig. 4). In contrast, PTA values were negatively correlated with the GM volume of the bilateral superior temporal gyri, left middle temporal gyrus, bilateral inferior temporal gyrus, right Heschl’s gyrus, bilateral anterior insula and bilateral hippocampus. These results demonstrate that greater hearing damage is associated with a more marked reduction of GM in predominantly auditory cortices.

Correlations between hearing damage duration and gray matter volume

Regression analyses with hearing damage duration as the independent variable and GM volume as the dependent variable revealed that hearing damage duration was positively correlated to the GM volume of the right middle occipital gyrus and right middle temporal gyrus but was negatively correlated to the GM volume of the bilateral anterior cingulate cortex, extending to the supplementary motor area (Table 6, Fig. 5). These data indicate that hearing damage duration is related to the compensation by the visual system and volume reduction in brain regions that subserve high-level cognitive functions.

Correlations between speech recognition in noise and gray matter volume

For better representation of the types of hearing challenges UHL individuals experience in their daily lives, a speech-recognition in noise test (MHINT) was used to reflect the hearing adaptation besides pure tone. We chose Heschl’s gyrus and the anterior cingulate cortex from differences between UHL and NC groups (shown in Fig. 2) as the regions of interest (ROIs) to examine the relationship between MHINT and GM volume of cognitive and perceptive cortices. The results demonstrate that the bilateral hearing threshold of speech in quiet was negatively correlated with the GM volume of the anterior cingulate cortex (Fig. 6a); however, there was no correlation between speech recognition in noise and Heschl’s gyrus (Fig. 6b). These results confirmed that poorer speech recognition in noise was associated with greater reduction of GM in the anterior cingulate, which is involved in cognitive functions.

(a) Bilateral hearing threshold of speech in quiet was negatively correlated with the GM volume of the anterior cingulate cortex (r = −0.51, p = 0.005). (b) No significant correlation was found between the GM volume of Heschl’s gyrus and the bilateral hearing threshold of speech in quiet (r = 0.03, p = 0.87). The ROIs were extracted based on the whole-brain analysis of group differences in GM volume between the UHL and NC groups.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the experience-dependent brain plasticity in UHL participants using an MRI-based morphometric analysis. While the GM volume reductions in primary sensory regions were significantly correlated with subjective hearing ability, the hearing damage duration was related to decreased GM volumes in cortical areas involved in high-order cognitive processing. These results suggest that the severity and duration of UHL respectively contribute to alterations in the GM volume of auditory and high-level functional structures.

Most previous studies have focused on completely deaf individuals, and those volumetric studies revealed either preserved19,20,21 or decreased7 GM volume of the auditory cortex in deaf individuals. Our findings with respect to the neuroplasticity of individuals with varying scales of UHL demonstrated the influential role of auditory inputs on GM volume, especially in the temporal lobe. The temporal lobe, which receives and processes auditory information, is the key area for central auditory perception22. The correlation between severity of hearing damage and decreased GM volume in temporal lobe in UHL patients suggests that peripheral hearing ability plays a noticeable role in GM volume reduction in the auditory cortex. Similar to the findings that changes in GM density are associated with hearing damage in the elderly23,24,25, cortical structures cannot preserve their typical morphology after unilateral auditory deprivation because of defective compensation for post-lingual unbalanced sensory input, and auditory deprivation gradually attenuates cortical connections in UHL individuals. Consistent with the tonotopic reorganization of the auditory cortex following peripheral hearing loss26, our data support the idea that compromised sensory input induces a reorganization of the sensory cortex27, especially following asymmetric hearing damage28. Furthermore, the brain is organized cooperatively to facilitate responses to sensory input29. Cross-modal reorganization in the remaining intact sensory systems likely mediates neural compensation30. Increased listening effort is often associated with increased activity in the premotor cortex31,32,33, which is consistent with the increased GM volume in the supplementary motor and precentral gyri in the current study and suggests compensatory neuroplastic reorganization.

Additionally, UHL might disrupt more elaborate auditory information, such as musical perception, vocal communication sounds and spatial and temporal auditory processing. These high-level auditory processes involve many brain regions, particularly the insula, as shown in lesion studies34,35,36,37. The insula plays a critical role in multi-sensory integration of emotional factors38,39,40,41, and it is a hub that links information from diverse cognitive functional systems42. This region plays an important role in several independent but interrelated cognitive control networks38,39,43. In our previous UHL study13, we demonstrated increased regional homogeneity in the anterior insular cortex as well as enhanced resting-state functional connectivity between the insula and several key regions of the default-mode network, empathizing the significant reorganization of insular cortex during UHL. Therefore, we infer that the correlation between GM volume and insula of UHL participants originates from the obstruction of the engagement of diverse cognitive processes related to perceptional deficits.

Previous studies have shown that the anatomical and functional changes observed in deaf individuals are present in basic sensory and higher-level cognitive processing13,24. Likewise, UHL patients suffer from difficult listening conditions in the absence of intact acoustic input, and UHL might induce cognitive dysfunction because unbalanced auditory input affects integral auditory perception12 and higher-order representations of auditory processing2,44,45. Thus, neuroplasticity in UHL patients can be mediated by both sensory and cognitive mechanisms, as they cannot communicate through sound as usual and must develop behavioral adaptations. The duration of hearing damage in our study was associated with cortical atrophy mainly in the bilateral anterior cingulate cortex, right superior frontal gyrus and bilateral middle frontal gyrus, which are critical structures for cognitive processing46. Consistent with the correlation between hearing damage duration and GM volume, decreased speech recognition ability is associated with a more marked reduction in the GM volume of the bilateral anterior cingulate cortex. The findings that cortices associated with high-level cognition are susceptible to speech-recognition ability support our hypothesis that the prolonged partial hearing damage alters the auditory cortex as well as impact on high-level functions. GM changes in the prefrontal cortex have been associated with impairments in decision-making47, executive function48,49, social cognition50, empathizing51 and other cognitive control processing52 in previous disease-related studies. Accordingly, our findings suggest that abnormal cognitive control may be a traumatic consequence of the reshaping of cortical structures in response to input signals that are aligned with behavioral adaptation13,53.

None of the post-lingual UHL participants in our study were in the critical period of auditory development; thus, the sensory system may be too stable to adequately modulate plastic modality. Post-lingual UHL induces a decline in the ability to process advanced auditory processing, such as phonological analysis and phonological processing for visual communication (i.e., speech-reading)54. This decline may parallel to dynamic cognitive processing, and the higher-order representations would be modified as the duration of hearing damage progresses. Reduced hearing input obstructs the interaction between the brain and the outside world, which desensitizes the detection of the dynamic environment. Thus, we speculate that the perceptional deficit in UHL compels patients to pay more attention to internal information. Therefore, the correlation between frontal lobe GM volume and hearing loss duration in UHL participants may indicate a sensory experience-driven plasticity that resulted at least in part from specific cognitive factors (i.e., down-regulated cognitive processing for perceptual recognition and bottom-up mechanisms developed because of the experienced perceptional deficits).

We also observed an approximate inversion symmetry of cortical reorganization between participants with UHL on different sides. The structural changes in the perirhinal cortex/parahippocampus were specific to the laterality of UHL. The perirhinal cortex is a critical association area for the cross-modal integration of highly processed sensory information55. Reduced auditory input impairs sensory integrity and clearly attenuates object-recognition abilities. Therefore, this reduced input enhanced the associative flexibility in the perirhinal cortex to facilitate the identification of environmental stimuli and maintain the balance of auditory information. Eventually, the contralateral neural pathway of auditory processing drives the increased GM volume in anatomically distinguishable substrates, i.e., the perirhinal cortex of the right/left hemisphere that resulted from left/right UHL.

There are some limitations in this study. We investigated the brain morphological changes and their correlations to hearing damage in AN patients. Growth of the tumor in the cerebellopontine angle is likely to change anatomical relationships in the brain. However, the tumors grow subtentorially, thus requiring long-term growth to affect hemispheric structures. Considering patients with UHL without a growing tumor in the brain would increase the probability that the changes in morphometry are not by chance and not due to tumor growth, and further studies including data on UHL in the absence of a neurinoma would be helpful. Moreover, the reorganization of higher-level cognitive processing areas is generally convincing in the face of severe and persistent UHL, and we performed basic speech-in-noise tests to obtain more direct evidence supporting this claim. Future studies may provide detailed information by measuring the higher-order auditory processing more specifically.

In conclusion, our results indicate that UHL induces plasticity in low-level sensory and high-level representation systems to adapt to the impaired auditory input. In addition, brain remodeling occurs in anatomically distinguishable substrates in response to the severity and duration of hearing damage.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Patients with unilateral acoustic neuroma (AN) provided consent and were hospitalized in our neurosurgery department (Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, China) between July 2014 and December 2014. We collected MRI data from 48 patients in total. All the patients were preoperatively diagnosed with UHL resulting from intracranial tumors based on MRI scanning and auditory assessment (pure tone audiometry, described below). Six of the patients were confirmed pathologically as having meningioma and were excluded from the experiment. Therefore, we reported results of the other 42 UHL patients with the same etiology. Twenty-one patients had hearing damage in the left ear, and 21 patients had hearing damage in the right ear. Twenty-four normal control (NC) participants were recruited from the local community in Beijing, with age, gender and education matched to the patients. All the controls also underwent the same MRI and auditory tests. These assessments were necessary for the patients during their clinical management, with no additional cost for them, and the control group received all the tests for free. The study was conducted on the UHL patients with AN preoperatively, and all the UHL participants had undergone the craniotomy to remove the neuromas after the MRI and auditory exam according to the clinical arrangement. All participants were right-handed and reported no previous or current psychiatric disorders (see Table 1 for participant demographics and auditory characteristics). Participants were informed of the requirements and provided written consent prior to participation. The Institutional Review Board of Beijing Tiantan Hospital of Capital Medical University approved this study, and the study procedures were carried out in accordance with the approved programs.

Clinical assessment

Pure tone audiometry (PTA)

We used a standard Hughson-Westlake PTA procedure to identify bilateral hearing threshold levels in each participant. A clinical audiologist collected air-conduction pure-tone audiograms under standard conditions. Audiometric measurements were performed using a GSI-61 audiometer with a TDH39 headphone. The audiological equipment was calibrated. Pure-tone audiometry was conducted at frequencies of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 kHz. Acoustic thresholds of the affected ear were compared to the contralateral unaffected ear at each frequency level. The mean acoustic threshold in speech frequency ([0.5 kHz + 1 kHz + 2 kHz + 4 kHz]/4) was calculated for each participant as the primary audiometric measure. In general, higher PTA values imply worse hearing ability.

Mandarin hearing in noise test (MHINT)

MHINT was conducted by using the bilateral implant test system (BLIMP) which was developed by House Ear Institute56, University of Hong Kong57 and Beijing Tongren Hospital58. BLIMP makes the speech and noise signals from the built-in sound card transfer to the external stimulation signal port of a Conera audiometer, and audiometric measurements were performed using a headphone. All the audiological equipment was calibrated using a B & K 4134 pressure-type microphone and a B & K 4153 artificial ear. There are 12 sentence lists in MHINT, each containing 20 sentences, and there are 10 words in each sentence. These sentences were recorded using a male professional voice actor who spoke Mandarin, an unaccented dialect free of noticeable regional influences. At the beginning, the hearing threshold was defined as the participants being able to repeat 50% of the key words in the sentence in quiet. The maximum noise level that cannot impact the 50% accuracy is defined as the background noise, and the starting noise ratio is zero. Then, BLIMP automatically adjusts the speech sound intensity (background noise is fixed, to change the signal-to-noise ratio) according to the participants’ accuracy of repeating the key words in the sentences. The judgment rule was settled as 50–74% in BLIMP (MHINT moves to the next sentence if the accuracy rate is between 50–74%; otherwise, BLIMP turns the speech sound volume up or down). The first four sentences were used as the adaptability test, and speech sounds were adjusted by 4 dB between each pair of sentences. If the first four sentences are all right or all wrong, the test will stop automatically, and MHINT will restart with resetting the intensity of the speech sound. Beginning with the fifth sentence, the adjusted standard is 2 dB, and the left and right ears are tested separately. The final result is the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR, measured as S dB/N), and lower SNRs indicate better speech recognition ability. Unfortunately, because some patients who only speak dialects had difficulty understanding the Mandarin and some patients could not complete the whole test, we only collected MHINT data from 13 left and 15 right UHL patients.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

An MMSE59 was conducted to assess differences in general cognitive ability between the UHL and NC groups. The MMSE is a commonly used clinical screen for cognitive impairment59. The MMSE includes 11 items that assess eight categories of cognition: orientation to time, orientation to place, registration, attention and calculation, recall, language, repetition, and complex commands. The maximum score is 30 points, and a low score indicates cognitive impairment.

MRI acquisition

All structural images were acquired using the same 3.0 Tesla Siemens TRIO scanner (Erlangen, Germany) with a standard head coil in a single scanning session. Head fixation with foam pads and hearing protection with earplugs were used for each participant. T1-weighted sagittal anatomical images were obtained using the following gradient echo sequence: 176 slices, slice thickness/gap = 1/0 mm, inversion time = 900 ms, repetition time = 2300 ms, echo time = 3 ms, flip angle = 7°, number of excitations = 1, field of view = 240 × 240 mm2 with an in-plane resolution of 0.9375 × 0.9375 mm2.

VBM analysis

Images were analyzed using the voxel-based morphometry toolbox (VBM8; http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/) with a statistical parametric mapping package (SPM8; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/). The structural MRI scan of each participant was preprocessed using a modified optimized-VBM-protocol15, which may reduce scanner-specific bias60. A 12-parameter affine transformation and nonlinear deformations were applied to normalize images to the stereotactic space (152 T1 MNI template, Montreal Neurological Institute). A modulation was applied to the partitioned images by multiplication with the relative voxel volumes or Jacobian determinants of the deformation field to preserve the absolute volume of gray matter within each structure14. Modulated images were segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid using a modified mixture model cluster analysis technique14. In the current study, we only analyzed GM volume, based on our interests. We applied an isotropic smoothing Gaussian kernel of 8 mm full-width-at-half maximum (FWHM) to the normalized GM segments to reduce signal noise and artifacts from head movements and residual inter-subject variability that was introduced by normalization.

Two-sample t-tests were performed to test volumetric differences between left and right UHL patients and between UHL and NC groups. Regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between audiometric measures (PTA and MHINT) and GM volume in left and right UHL groups. AFNI AlphaSim (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/doc/edu) was used for Monte Carlo simulation with 1,000 iterations to correct for multiple comparisons across the thresholded GM mask, which only included voxels with a probability higher than 0.4 in the SPM8 GM template. A cluster extent of 328 contiguous resampled voxels (1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3) was considered significant assuming an individual voxel type I error of p < 0.01, which corresponds to a corrected p < 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, X. et al. Alterations in gray matter volume due to unilateral hearing loss. Sci. Rep. 6, 25811; doi: 10.1038/srep25811 (2016).

References

King, A. J. & Moore, D. R. Plasticity of auditory maps in the brain. Trends Neurosci 14, 31–37 (1991).

Bengoetxea, H. et al. Enriched and Deprived Sensory Experience Induces Structural Changes and Rewires Connectivity during the Postnatal Development of the Brain. Neural Plast 2012, 305693.

Kral, A., Hartmann, R., Tillein, J., Heid, S. & Klinke, R. Hearing after congenital deafness: central auditory plasticity and sensory deprivation. Cereb Cortex 12, 797–807 (2002).

Lee, J. S. et al. PET evidence of neuroplasticity in adult auditory cortex of postlingual deafness. J Nucl Med 44, 1435–1439 (2003).

Kotak, V. C., Breithaupt, A. D. & Sanes, D. H. Developmental hearing loss eliminates long-term potentiation in the auditory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 3550–3555 (2007).

Allen, J. S., Emmorey, K., Bruss, J. & Damasio, H. Neuroanatomical differences in visual, motor, and language cortices between congenitally deaf signers, hearing signers, and hearing non-signers. Front Neuroanat 7, 26 (2013).

Olulade, O. A., Koo, D. S., LaSasso, C. J. & Eden, G. F. Neuroanatomical profiles of deafness in the context of native language experience. J Neurosci 34, 5613–5620 (2014).

Langers, D. R. & Melcher, J. R. Hearing without listening: functional connectivity reveals the engagement of multiple nonauditory networks during basic sound processing. Brain connectivity 1, 233–244 (2011).

Miller, P. & Wingfield, A. Distinct effects of perceptual quality on auditory word recognition, memory formation and recall in a neural model of sequential memory. Front Syst Neurosci 14 (2010).

Zekveld, A. A., Kramer, S. E. & Festen, J. M. Cognitive load during speech perception in noise: the influence of age, hearing loss, and cognition on the pupil response. Ear Hear 32, 498–510 (2011).

Welsh, L. W., Welsh, J. J., Rosen, L. F. & Dragonette, J. E. Functional impairments due to unilateral deafness. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 113, 987–993 (2004).

Salvador, K. K., Pereira, T. C., Moraes, T. F., Cruz, M. S. & Feniman, M. R. Auditory processing in unilateral hearing loss: case report. J Soc Bras Fonoaudiol 23, 381–384 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. Altered regional and circuit resting-state activity associated with unilateral hearing loss. PLoS One 9, e96126 (2014).

Ashburner, J. & Friston, K. J. Voxel-based morphometry–the methods. NeuroImage 11, 805–821 (2000).

Good, C. D. et al. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. NeuroImage 14, 21–36 (2001).

Minzenberg, M. J., Fan, J., New, A. S., Tang, C. Y. & Siever, L. J. Frontolimbic structural changes in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 42, 727–733 (2008).

Bacciu, S. et al. Progressive sensorineural hearing loss: neoplastic causes. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 18, 71–76 (1998).

Breivik, C. N., Varughese, J. K., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Vassbotn, F. & Lund-Johansen, M. Conservative management of vestibular schwannoma–a prospective cohort study: treatment, symptoms, and quality of life. Neurosurgery 70, 1072–1080 (2012).

Emmorey, K., Allen, J. S., Bruss, J., Schenker, N. & Damasio, H. A morphometric analysis of auditory brain regions in congenitally deaf adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 10049–10054 (2003).

Penhune, V. B., Cismaru, R., Dorsaint-Pierre, R., Petitto, L. A. & Zatorre, R. J. The morphometry of auditory cortex in the congenitally deaf measured using MRI. NeuroImage 20, 1215–1225 (2003).

Shibata, D. K. Differences in brain structure in deaf persons on MR imaging studied with voxel-based morphometry. AJNR. 28, 243–249 (2007).

Seltzer, B. & Pandya, D. N. Afferent cortical connections and architectonics of the superior temporal sulcus and surrounding cortex in the rhesus monkey. Brain Res 149, 1–24 (1978).

Peelle, J. E., Troiani, V., Grossman, M. & Wingfield, A. Hearing loss in older adults affects neural systems supporting speech comprehension. J Neurosci 31, 12638–12643 (2011).

Cardin, V. et al. Dissociating cognitive and sensory neural plasticity in human superior temporal cortex. Nat Commun 4, 1473 (2013).

Hribar, M., Suput, D., Carvalho, A. A., Battelino, S. & Vovk, A. Structural alterations of brain grey and white matter in early deaf adults. Hea Res 318, 1–10 (2014).

Schwaber, M. K., Garraghty, P. E. & Kaas, J. H. Neuroplasticity of the adult primate auditory cortex following cochlear hearing loss. Am J Otol 14, 252–258 (1993).

Rauschecker, J. P. Compensatory plasticity and sensory substitution in the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci 18, 36–43 (1995).

Cheung, S. W., Bonham, B. H., Schreiner, C. E., Godey, B. & Copenhaver, D. A. Realignment of interaural cortical maps in asymmetric hearing loss. J Neurosci 29, 7065–7078 (2009).

Zhang, D. & Raichle, M. E. Disease and the brain’s dark energy. Nat Rev Neurol 6, 15–28 (2010).

Lomber, S. G., Meredith, M. A. & Kral, A. Cross-modal plasticity in specific auditory cortices underlies visual compensations in the deaf. Nat neurosci 13, 1421–1427 (2010).

Davis, M. H. & Johnsrude, I. S. Hierarchical processing in spoken language comprehension. J Neurosci 23, 3423–3431 (2003).

Davis, M. H. & Johnsrude, I. S. Hearing speech sounds: top-down influences on the interface between audition and speech perception. Hear Res 229, 132–147 (2007).

Peelle, J. E., Johnsrude, I. S. & Davis, M. H. Hierarchical processing for speech in human auditory cortex and beyond. Front Hum Neurosci 4, 51 (2010).

Habib, M. et al. Mutism and auditory agnosia due to bilateral insular damage–role of the insula in human communication. Neuropsychologia 33, 327–339 (1995).

Manes, F., Paradiso, S., Springer, J. A., Lamberty, G. & Robinson, R. G. Neglect after right insular cortex infarction. Stroke 30, 946–948 (1999).

Bamiou, D. E. et al. Auditory temporal processing deficits in patients with insular stroke. Neurology 67, 614–619 (2006).

Wong, P. C., Parsons, L. M., Martinez, M. & Diehl, R. L. The role of the insular cortex in pitch pattern perception: the effect of linguistic contexts. J Neurosci 24, 9153–9160 (2004).

Taylor, K. S., Seminowicz, D. A. & Davis, K. D. Two systems of resting state connectivity between the insula and cingulate cortex. Hum Brain Mapp 30, 2731–2745 (2009).

Cauda, F. et al. Meta-analytic clustering of the insular cortex: characterizing the meta-analytic connectivity of the insula when involved in active tasks. NeuroImage 62, 343–355 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Recovery of empathetic function following resection of insular gliomas. J Neurooncol 117, 269–277 (2014).

Gu, X. et al. Anterior insular cortex is necessary for empathetic pain perception. Brain 135, 2726–2735 (2012).

Flynn, F. G., Benson, D. F. & Ardila, A. Anatomy of the insula-functional and clinical correlates. Aphasiology 13, 55–78 (1999).

Fan, J. et al. Quantitative Characterization of Functional Anatomical Contributions to Cognitive Control under Uncertainty. J Cogn Neurosci 26, 1490–506 (2014).

Scott, G. D., Karns, C. M., Dow, M. W., Stevens, C. & Neville, H. J. Enhanced peripheral visual processing in congenitally deaf humans is supported by multiple brain regions, including primary auditory cortex. Front Hum Neurosci 8, 177 (2014).

Giuliano, R. J., Karns, C. M., Neville, H. J. & Hillyard, S. A. Early Auditory Evoked Potential Is Modulated by Selective Attention and Related to Individual Differences in Visual Working Memory Capacity. J Neurosci 26, 2682–2690 (2014).

Fan, J., McCandliss, B. D., Fossella, J., Flombaum, J. I. & Posner, M. I. The activation of attentional networks. NeuroImage 26, 471–479 (2005).

Muhlert, N. et al. The grey matter correlates of impaired decision-making in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 86, 530–536 (2015).

Zimmerman, M. E., DelBello, M. P., Getz, G. E., Shear, P. K. & Strakowski, S. M. Anterior cingulate subregion volumes and executive function in bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders 8, 281–288 (2006).

Rusch, N. et al. Prefrontal-thalamic-cerebellar gray matter networks and executive functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 93, 79–89 (2007).

Fujiwara, H. et al. Anterior cingulate pathology and social cognition in schizophrenia: a study of gray matter, white matter and sulcal morphometry. NeuroImage 36, 1236–1245 (2007).

Takeuchi, H. et al. Regional gray matter volume is associated with empathizing and systemizing in young adults. PLoS One 9, e84782 (2014).

Chetelat, G. et al. Mapping gray matter loss with voxel-based morphometry in mild cognitive impairment. Neuroreport 13, 1939–1943 (2002).

Tan, L. et al. Combined analysis of sMRI and fMRI imaging data provides accurate disease markers for hearing impairment. NeuroImage Clin 3, 416–428 (2013).

Lazard, D. S., Lee, H. J., Truy, E. & Giraud, A. L. Bilateral reorganization of posterior temporal cortices in post-lingual deafness and its relation to cochlear implant outcome. Hum Brain Mapp 34, 1208–1219 (2012).

Taylor, K. I., Stamatakis, E. A. & Tyler, L. K. Crossmodal integration of object features: voxel-based correlations in brain-damaged patients. Brain 132, 671–683 (2009).

Vermiglio, A. J. The American English hearing in noise test. Int J Audiol 47, 386–387 (2008).

Wong, L. L., Soli, S. D., Liu, S., Han, N. & Huang, M. W. Development of the Mandarin Hearing in Noise Test (MHINT). Ear Hear 28, 70S–74S (2007).

Zhang, N. et al. Assessment of cochlear implant performance with Mandarin Hearing In Noise Test. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery 25, 1030–1033 (2011).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198 (1975).

Ashburner, J. & Friston, K. J. Unified segmentation. NeuroImage 26, 839–851 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Support Program of the 12th Five-Year of China (grant number: 2012BAI12B03) to P.L., the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (grant number: 7112049) to P.L., and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 81328008) to J.F.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. and P.Xu wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Tables 2–5 and all figures. Z.W. and P.Li prepared Table 1. X.W., Z.W., P.Li and F.Z. collected the MRI and audiometric data. X.W. and F.Z. collected the clinical data. Y.-j.L., J.F. and P.Liu guided the data analysis. Z.G. and L.X. helped to improve the scientific structure of the manuscript. Z.G., L.X., Y.-j.L., J.F. and P.Liu discussed the results and finalized the conclusion of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Xu, P., Li, P. et al. Alterations in gray matter volume due to unilateral hearing loss. Sci Rep 6, 25811 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25811

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25811

This article is cited by

-

The characteristics of brain structural remodeling in patients with unilateral vestibular schwannoma

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2023)

-

Cortical and subcortical gray matter changes in patients with chronic tinnitus sustaining after vestibular schwannoma surgery

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Associations of noise kurtosis, genetic variations in NOX3 and lifestyle factors with noise-induced hearing loss

Environmental Health (2020)

-

Gray matter declines with age and hearing loss, but is partially maintained in tinnitus

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Abnormal functional connectivity and degree centrality in anterior cingulate cortex in patients with long-term sensorineural hearing loss

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.