Abstract

Schistosomiasis remains a major public health problem and causes substantial economic impact in east China, particularly along the Yangtze River Basin. Disease forecasting and surveillance can assist in the development and implementation of more effective intervention measures to control disease. In this study, we applied a Bayesian hierarchical spatio-temporal model to describe trends in schistosomiasis risk in Anhui Province, China, using annual parasitological and environmental data for the period 1997–2010. A computationally efficient approach–Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation–was used for model inference. A zero-inflated, negative binomial model best described the spatio-temporal dynamics of schistosomiasis risk. It predicted that the disease risk would generally be low and stable except for some specific, local areas during the period 2011–2014. High-risk counties were identified in the forecasting maps: three in which the risk remained high, and two in which risk would become high. The results indicated that schistosomiasis risk has been reduced to consistently low levels throughout much of this region of China; however, some counties were identified in which progress in schistosomiasis control was less than satisfactory. Whilst maintaining overall control, specific interventions in the future should focus on these refractive counties as part of a strategy to eliminate schistosomiasis from this region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schistosomiasis, caused by parasitic blood flukes in the Schistosoma genus1, is a zoonotic disease. It remains a serious public health problem worldwide, being endemic mainly in developing countries located in tropical and subtropical regions2. According to the World Health Organization, as of 2012 there were at least 249 million people infected and more than 700 million people at risk3. The global burden of schistosomiasis has been estimated to be 3.31 (95% confidence interval 1.70–6.26) million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)4. In China, schistosomiasis japonica is responsible for human and animal infections5. The disease has a documented history of over 2,100 years along the Yangtze River Basin6 and is still regarded as an important parasitic disease. A recent study estimated that there were approximately 185,000 schistosomiasis japonica cases nationwide7.

With the implementation of a wide range of schistosomiasis control programs, schistosomiasis prevalence has been greatly reduced8 and is currently at a low infection level9. However, challenges to control remain and many factors could lead to a resurgence of schistosomiasis, including changes in patient susceptibility to infection and re-infection, effects of global warming, increasing population mobility, and changes in snail habitat and distribution via ecosystem changes as a result of human activities (e.g., the Three Gorges Dams and the South–North Water Conversion Project)10,11. To eliminate schistosomiasis has proven to be a tough task. National and local surveillance systems have played an important role in schistosomiasis control and elimination12,13. However, the current surveillance systems predominantly focus on parasitological data collection, such as case reports collected at local anti-schistosomiasis stations (e.g., township) and data aggregated at higher administrative units (e.g., county)14,15; these data are considered to be inefficient for surveillance. An efficient and timely surveillance system integrating early warning and multi-data streams is needed to improve the implementation and evaluation of targeted control strategies16.

Forecasting, as a means of surveillance and early detection, can facilitate the formulation of effective control strategies for schistosomiasis. Time series analysis17,18,19 and its derivatives20 are currently the predominant approaches. Although these approaches consider the temporal dimension they neglect the geographical clustering characteristic of schistosomiasis. Some researchers21 in China have forecasted the risk of S. japonicum infection by modeling the temporal and spatial dimensions separately, ignoring the spatio-temporal interaction dimension. In contrast, in the current study we built a hierarchical Bayesian (HB) spatio-temporal model to investigate the dynamic pattern of human schistosomiasis risk in Anhui Province, East China, a typical schistosomiasis-endemic area along the Yangtze River Basin. First, we described schistosomiasis risk in Anhui using annual county-level parasitological data for the period 1997–2010, and briefly discuss the HB spatio-temporal model and modeling approaches. We then used the best predictive model to forecast schistosomiasis risk for the period 2011–2014. In closing, we discuss the potential implications of our findings for schistosomiasis control.

Results

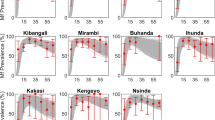

Figure 1 shows the endemic area of schistosomiasis japonica within our study region. Figure 2 depicts the change in annual prevalence of schistosomiasis risk during the study period. The median prevalence showed an increasing trend from 0.016% in 1997 to 0.115% in 2002; it then decreased gradually to 0.019% in 2010. There was a resurgence in prevalence (0.142%) in 2005. A higher prevalence was accompanied by a wider interquartile range (IQR). Overall, the schistosomiasis risk fluctuated through the study period.

Figure 3 is a map of observed relative risk (RR) of schistosomiasis during the period 1997–2010. The spatial pattern of the disease risk was different across the study years. High levels of schistosomiasis risk (i.e., RR >1) were observed mainly in areas along the Yangtze River; areas of low levels of disease risk were located away from the river, mainly in the south and east parts of the study region. Some counties presented high and increasing risks during the study period, such as county 21 (county IDs are shown in Fig. 1) with RRs between 1 and 3 during 1997–2004 and rising to >3 there afterwards. Other counties–for example county 8–showed a fluctuating risk during 1997–2006 and then maintained a high relative risk during the remaining years. Geographically, the spatial extent of high risk decreased and became focal during the study period.

We used a dynamical spatio-temporal model (denoted as m1) to study the trends in schistosomiasis risk in the study region. For a comparison, we also specified a non-dynamical spatio-temporal model (denoted as m2), a spatial model (denoted as m3), and a temporal model (denoted as m4). In addition, we evaluated these models’ zero-inflated version. For model selection, all the models were fit to RRs of schistosomiasis for the period 1997–2008 (T = 12). A comparison was made between observed RR values of the last two years (2009 and 2010) and RRs predicted by the models at T + 1 and T + 2. For each of these evaluations, we calculated the mean squared predictive errors (MSPEs), which measure model accuracy. In addition, the deviance information criterion (DIC)22 was considered.

The MSPE and DIC results of all models are presented in Table 1. As indicated by MSPEs, the zero-inflated models performed better than their ordinary model counterparts. With the zero-inflated negative binomial (NB) likelihood, the dynamical spatio-temporal model (m1) outperformed other models, with the smallest MSPEs of 3.96 in 2009 and 0.85 in 2010. Hence, model m1 with a zero-inflated NB likelihood was selected as the best predictive model (BPM) for forecasting. Interestingly, this model also fitted the data best as indicated by the smallest DIC.

Table 2 shows the results of the BPM using data for the period 1997–2010. Temperature and rainfall were not significantly associated with risk. Distance to the Yangtze River was negatively correlated with schistosomiasis risk. The schistosomiasis risk decreased over time but this change was not statistically significant. The posterior mean of the overdispersion parameter (r) was 2.56 and the 95% credible interval (CI) was 1.86 to 3.43, namely the overdispersion parameter was significantly greater than zero. The posterior mean of the zero-inflated parameter α was also significantly different from zero (posterior mean 2.36, 95% CI 1.59 to 3.35). The posterior mean of the transition parameter ρ was 0.91 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.95), indicating a stationary temporal process. The posterior mean of the variance parameter κ2 was 0.24 (95% CI, 0.15, 0.36).

Figure 4 displays the annual map of predicted RRs of schistosomiasis for the period 2011–2014. Most of the endemic counties had RRs <1, indicating relatively low schistosomiasis risk. Counties 21 and 12 had the highest risk (RR >3) and counties 8, 10, and 2 were also high-risk areas (RR ranging from 1 and 3). Figure 5 presents corresponding coefficients of variation (CV) of the forecasting. As expected, the maps present a rising trend over time: a higher level of uncertainty in forecasting occurs over time.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the spatio-temporal dynamics of schistosomiasis risk in Anhui Province, China, and then to forecast risk using a Bayesian spatio-temporal model with a computationally efficient and statistically powerful inference approach. In this approach, it is assumed that observations are determined by a hidden latent process, which is important for understanding the etiology of a phenomenon23. Our results identified the spatio-temporal pattern of schistosomiasis risk after adjusting for some important environmental factors and the forecasting risk maps provided useful information for future schistosomiasis monitoring and control.

The spatial variation of schistosomiasis risk and the association between environmental factors and the disease can be explained by the known biology of schistosoma and freshwater snails (i.e., O.hupensis). Higher temperature and more rainfall are conducive to the parasite’s life cycle and formation of snail habitat. However, abnormal weather conditions can have negative effects on both the parasite and the snail24,25. During 1997–2010, temperature in the region was very low in 2005 and rainfall was extremely heavy in 2009. This might explain why temperature and rainfall were not significantly positively associated with schistosomiasis risk in our analysis. We found that distance to the Yangtze River was significantly negatively correlated with disease risk, likely because of an increased risk of contacting infected water via swimming, fishing and agricultural activities. Of note, there was some spatio-temporal random effect (ηit in formula [3]) that could not be explained by the fixed variables. The estimate of transition parameter ρ shows that formula 3 is stationary, indicating that the small-scale spatio-temporal variation of schistosomiasis risk was stable over time, i.e. it was not explosive or decaying.

Schistosomiasis disease risk tended to decrease over time but the change was not statistically significant. The study area was subject to two important, national schistosomiasis control programs during the period 1997–2010. The first one was a 10-year World Bank Loan Project (WBLP) launched in 1992, largely based on large-scale chemotherapy. The second was a revised control strategy which was initiated in 2005, using integrated measures and an emphasis on controlling the source of infection. In addition, each county used available funds to undertake individual control strategies14. As the drug-based strategy is a host-targeted treatment, it can only control the disease to a certain extent. Studies26,27 have shown that schistosomiasis risk rebounded shortly after the WBLP was completed in 2001. Our study shows that the median prevalence reached a peak in 2002 (Fig. 2). The revised strategy focused largely on interrupting the life cycle of the parasite28,29. An important measure was to replace water buffalo (a prevalent infection source in the lake and marshland area) with agricultural machinery. A reduced median prevalence with narrowed IQR after 2005–demonstrated in our results (Fig. 2)–suggests that the latter program was likely more effective. A limitation of the revised control strategy is that the intervention measures cannot completely block the life cycle of the parasite since more than 40 species of mammals30 can serve as potential zoonotic reservoirs, in addition to water buffalo and humans. Infected O. hupensis snails were still found in certain locations along the Yangtze River31. These two features might prevent further reduction of schistosomiasis risk.

The focus of our study was to forecast schistosomiasis risk. As shown in Fig. 4, the risk for some counties remained elevated (i.e., RR >1; for example, counties 21, 12 and 8); these should be priority areas for the implementation of control measure. Unexpectedly, historically low-risk counties (counties 10 and 2 in this study) became high risk counties; these require close monitoring in a disease control program. The rising uncertainties in the forecasting of disease risk over time (Fig. 5) indicates that the accuracy of risk prediction may be reliable for a short-term forecast but not for a long-term forecast, which may limit its utility for decision-making in some circumstances. Such uncertainties need to be carefully assessed when interpreting maps for disease control32.

We included the spatio-temporal dependence in formula 3 that shows how the current value ηit behaves given the behavior of “nearby” current ηjt (j are spatial neighborhoods of i) and the most recent past values ηi,t − 1. This model characterizes the evolution of schistosomiasis risk over space and time. Another way to model the spatio-temporal dependence is to build a moment-based model (e.g., Kriging approach) and it has been used in some previous schistosomiasis risk studies33,34. The latter approach ignores the directionality of time and specifies only the first and second moments of ηit in the temporal domain of interest. It can ignore the genesis of the temporal dependence and generally performs much worse in forecasting35. We also made a comparison with a non-dynamical spatio-temporal model, a purely spatial model, and purely temporal model. MSPE results justified our adoption of the dynamical spatio-temporal model. DIC results also indicated that the dynamical spatio-temporal model is the best fitting model.

The spatio-temporal model accounted for overdispersion to a large extent, which has seldom been considered in previous studies of schistosomiasis risk forecasting. Instead of the standard Poisson distribution to model the potential extra-Poisson variation we assumed the number of infected individuals in each county follows a NB distribution. Additionally, a large proportion of individuals were considered to be non-infected due to heterogeneities in environmental exposure36 and imperfect diagnostic approaches for schistosomiasis37 (see Fig. 2). The zero-inflated parameter of the zero-inflated NB model (α = 2.36, 95% CI 1.59 to 3.35) was significantly different from zero suggesting that there were a significant number of zeros in the observed data that could not be included in the NB distribution. Besides the statistical consideration, the zero-inflation model is epidemiologically used for better understanding the presence and absence of infection in the study area and the count process accounts for the level (or strength) of the risk of infection. The MSPE and DIC (Table 1) results indicated that the zero-inflated NB model improved the performance for both data fitting and risk forecasting.

Some limitations of this study deserve discussion. First, only a few environmental factors (i.e., temperature, rainfall, and the Yangtze River) were included in our study, whilst socio-economic and socio-behavioral indicators–which might have an important impact on schistosomiasis risk as well as the effectiveness of targeted control measures–were absent. Second, the specificity of serological assays and the sensitivity of stool examination tests are not perfect38 and this uncertainty was not considered in our modeling. Modeling with diagnostic errors should be considered in future studies. Finally, we were not able to directly attribute the spatio-temporal changes in schistosomiasis risk to the two national control strategies and the environmental factors in the current analysis. Further studies are needed to understand the observed trend in disease risk.

In summary, we proposed a dynamical spatio-temporal model based on a hierarchy approach to forecast schistosomiasis risk in this study. Our model disclosed the spatio-temporal dynamics of schistosomiasis risk and the forecasting results identified three stable high-risk counties and two potential high-risk counties, which should be the priority areas for targeted interventions. The forecasting maps provide an empirical basis for monitoring schistosomiasis risk in the study area.

Methods

Study area

Anhui Province, located across the basins of the Huaihe River (in the North) and the Yangtze River (in the South), spans approximately 139,600 km2 in east China and has a population of 60.83 million (2014). The province is characterized by a range of landscapes: plains in the northern and north-central parts and mountains and a series of hills in the south-western and south-eastern parts. The province has a subtropical humid monsoon climate and “plum” rains occur in June and July and may cause flooding, which is conducive to growth of Oncomelania hupensis, the intermediate host of schistosomiasis japonica.

Parasitological data

The county-level schistosomiasis data were obtained from cross-sectional surveys conducted by the health professionals of the Anhui Institute of Parasitic Diseases repeated annually between 1997 and 2010. For each year, parasitological data were originally collected through village-based field surveys of randomly selected villages, using a two-pronged diagnostic approach (all residents aged 5 to 65 years were screened by a serological test and then confirmed by a fecal parasitological test [Kato-Katz technique]39, then were reported to township and finally to county. During our study period, the yearly numbers of sample villages and individual participants ranged between 1,610 and 2,000, and 1,045,708 and 1,575,012, respectively. For our analysis, we removed counties that had no infected individuals during the study period. Thirty-one counties were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Environmental data

Schistosomiasis is a well-known environment-related disease, the transmission of which is strongly associated with temperature, rainfall and access to water40,41,42. In our study, environmental data included rainfall, temperature and distance to the Yangtze River. Monthly rainfall and temperature data during the period 1997–2010 were obtained from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System (http://cdc.cma.gov.cn/home.do). With available data at 756 meteorological stations in China, inverse distance weighting (IDW) interpolation was used to derive estimates within the study area. ArcGIS software (version 10.0, ESRI Inc.; Redlands, CA, USA) was used to extract monthly-average rainfall and temperature for each county. Data on the Yangtze River were downloaded from Conservation Science Data Sets of World Wildlife Foundation at http://worldwildlife.org. For each county, the Euclidian distance from the centroid of the county to the Yangtze River was calculated using ArcGIS software.

Ethical statement

Approval for oral consent and other aspects of the surveys were granted by the Ethics Committee of Fudan University (ID: IRB#2011-03-0295). Written informed consent was also obtained from all participants.

Statistical analysis

Hierarchical spatio-temporal model structure

Assume that there is a true unobserved spatio-temporal process hidden behind the yearly counts of schistosomiasis cases, which is incorporated into the framework of an HB statistical model. The spatial domain is discrete and consists of the 31 counties in the study area. Consequently, the size of count data we model is fixed at 31. The basic representation of the HB model is typically composed of three levels23, namely the data level (whose conditional probability distribution given processes and parameters is independent), the process level (which determines change of data level given parameters), and the parameter level (which exists in the previous levels).

Data level

Let Zit denotes the number of infected individuals at time t, in county i, where i = 31 and t = 14. Specifically, the data level is assumed to be a product of independent negative binomial (NB) distributions considering the possible overdispersion in the observed counts. That is,

where Zit and Eit are the observed number of schistosomiasis cases and the expected number of schistosomiasis cases in the county i at time t, respectively, and r is the overdispersion parameter. Zit approaches a Poisson distribution as r approaches zero. Although NB models may be ideal for over-dispersion, they may not be suitable when the data include too many zero values43. Since the schistosomiasis data in our analysis are counts characterized by many zeros, we evaluated the NB distribution as well as its zero-inflated version. λit is the underlying RR at county i and time t, and it is the hidden process of interest. The conditional distribution of λit given parameters, i.e. the process level, is where the spatio-temporal dependence can be modeled.

Process model

The process model is:

where Xitk are fixed covariates that are specified as the environmental factors and βk are corresponding coefficients; time t (and its corresponding coefficient β4) is used as an ordinal variable. Xitk and t capture the large-scale spatio-temporal variation of schistosomiasis risk while ηit captures the small-scale variation which explains any spatio-temporal statistical dependence. The marginal spatial dependence is modeled according to an intrinsic conditional autoregressive (CAR) model44 and the temporal dependence is modeled as a Gaussian first-order autoregressive (i.e., AR(1)) process45:

where ρ is the transition parameter with |ρ| < 1 in case of stationarity and the instantaneous spatial correlation, εit, is independent from ηi,t − 1 and is distributed according to the Gaussian Markov random field,

where κ2 is the variance parameter at time t, N(i) denotes spatial neighborhoods of county i (here we assume that the neighborhood structure does not change over time), and w(i, j) is a weights matrix element and w*(i, j) is a standardized form of a weights matrix, defining the relationship between county i and its neighbor county j. The weight is defined simply as w(i, j) = 1 if the two counties are adjacent (i.e., share a common border) and w(i, j) = 0 otherwise. As formula 3 shows how the current value ηit is related mechanistically to its past value and its current spatial neighbors, we call it a dynamical spatio-temporal model.

Parameter level

At this level, we specify the joint prior distribution for the parameters in data level and process level to complete the HB model. The parameters include the overdispersion parameter {r}, the fixed-effect coefficients β = (β1, β2, β3, β4), the transition parameter {ρ}, and the variance parameter {κ2}. Recall that we also consider a zero-inflated version of NB likelihood at the data level, hence a parameter (denoted as {α}) that deals with extra zeros that are not generated by the NB distribution is also included (details about α can be found in Appendix A). Assuming independence and using [Y] as generic notation for the density of Y, we have

where the prior distributions of individual parameters are specified as follows:

Note that α is excluded from (6) for a NB likelihood.

Model inference

Instead of using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which are traditionally relied on in Bayesian computation, we employ the integrated nested laplace approximation (INLA) approach as the model inference method. Proposed by Rue and Martino46, INLA is an approach to perform fast and efficient Bayesian inference through the accurate approximation to the marginal posterior densities of (hyper) parameters and latent variables in latent Gaussian models. The advantage of INLA over MCMC is that INLA uses an approximation for inference and hence avoids the intense computational demands, convergence, and mixing problems sometimes encountered by MCMC algorithms46. More details about this approach and its applications can be found elsewhere46,47,48. All model fitting was performed using R software (R Development Core Team 2013), specifically the R-INLA package.

The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines in this journal.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hu, Y. et al. Monitoring schistosomiasis risk in East China over space and time using a Bayesian hierarchical modeling approach. Sci. Rep. 6, 24173; doi: 10.1038/srep24173 (2016).

References

Utzinger, J. & Keiser, J. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: common drugs for treatment and control. Expert Opin Pharmacother 5, 263–85 (2004).

Gray, D. J. et al. Schistosomiasis elimination: lessons from the past guide the future. Lancet Infect Dis 10, 733–736 (2010).

WHO. schistosomiasis. (2015) Available at: http:// www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/. (Accessed: 5th July 2015).

Krishnamurthi, R. V. et al. Global and regional burden of first-ever ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Glob Health 1, e259–81 (2013).

Gryseels, B., Polman, K., Clerinx, J. & Kestens, L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet 368, 1106–1118 (2006).

Chen, M. & Feng, Z. Schistosomiasis control in China. Parasitol Int 48, 11–19 (1999).

Lei, Z. et al. Endemic status of schistosomiasis in People’s Republic of China in 2013. Chin J Schisto Control 26, 591–597 (2014).

Zhang, W. & Wong, C. M. Evaluation of the 1992–1999 World Bank Schistosomiasis Control Project in China. Acta Trop 85, 303–313 (2003).

Li, S. Z. et al. Schistosomiasis in China: acute infections during 2005–2008. Chin Med J (Engl) 122, 1009–14 (2009).

McManus, D. P. et al. schistosomasis in the People’s Republic of China: the Era of the Three Gorges Dam. Clin Microbiol Rev 23, 442–466 (2010).

Collions, C., Xu, J. & Tang, S. Schistosomiasis control and the health system in P.R. China. Infect Dis Poverty 1, 8 (2012).

Wu, X. H., Chen, M. G. & Zheng, J. Surveillance of schistosomiasis in five provinces of China which have reached the national criteria for elimination of the disease. Acta Trop 96, 276–81 (2005).

Zhu, H., Cai, S. X. & Gao, X. B. Preliminary effect of comprehensive measures with emphasis on infectious source control for schistosomiasis control in Hubei Province. Chin J Schisto Control 21 (2009).

Zhang, Z. et al. Long-term impact of the World Bank Loan Project for schistosomiasis control: a comparison of the spatial distribution of schistosomiasis risk in China. PLos Negl Trop Dis 6, e1620 (2012).

Hu, Y. et al. Changing patterns of spatial clustering of schistosomiasis in Southwest China between 1999–2001 and 2007–2008: assessing progress toward eradication after the World Bank Loan Project. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11, 701–12 (2014).

Zhu, R., Zhao, G. M. & Huang, X. B. Development and prospect of surveillance network of schistosom iasis in China. Chin J Schisto Control 23 (2011).

Sai, X. Y. et al. Application of “time series analysis” in the prediction of schistosomiasis prevalence in areas of “breaking dikes or opening sluice for waterstore” in Dongting Lake areas, China. Chin J Epidemio 25, 863–6 (2004).

Medina, D. C., Findley, S. E. & Doumbia, S. State-space forecasting of Schistosoma haematobium time-series in Niono, Mali. PLos Negl Trop Dis 2, e276 (2008).

Hao, Y. et al. Causes and risks of schistosomiasis transmission in Poyang Lake region of Jiangxi Province, China. Chin J Schisto Control 21, 345–349 (2009).

Zhou, L. L. et al. A hybrid model for predicting the prevalence of schistosomiasis in humans of Qianjiang City, China. PLos One 9, e104875 (2014).

Yang, G. J. et al. A growing degree-days based time-series analysis for prediction of Schistosoma japonicum transmission in Jiangsu province, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 75, 549–55 (2006).

Spiegelhalter, D. J., Best, N. G., Carlin, B. P. & Van Der Linde, A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Stat Soc B 64, 583–639 (2002).

Berliner, L. M. Hierarchical Bayesian time-series models. In Maximum Entropy and Bayesian Methods 15–22 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, NL, 1996).

Pesigan, T. P. et al. Studies on Schistosoma japonicum infection in the Philippines. 2. The molluscan host. Bull World Health Organ 18, 481–578 (1958).

Zhou, X. N. et al. Potential impact of climate change on schistosomiasis transmission in China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78, 188–94 (2008).

Utzinger, J., Bergquist, R., Shu-Hua, X., Singer, B. H. & Tanner, M. Sustainable schistosomiasis control–the way forward. Lancet 362, 1932–4 (2003).

Zhou, X. N. et al. The current status of schistosomiasis epidemics in China. Chin J Epidemio 25, 555–8 (2004).

Zhang, S. et al. Observation on comprehensive measures of safe treatment of night-soil and water supply, replacement of bovine with machine for schistosomiasis control. Chin J Schisto Control 17, 437–442 (2005).

Chen, X. Y. et al. Schistosomiasis control in China: the impact of a 10-year World Bank Loan Project (1992–2001). Bull World Health Organ 83, 43–48 (2005).

Zhou, Y. B., Liang, S. & Jiang, Q. W. Factors impacting on progress towards elimination of transmission of schistosomiasis japonica in China. Parasit Vectors 5, 275 (2012).

Yang, K. et al. Spatio-temporal analysis to identify determinants of Oncomelania hupensis infection with Schistosoma japonicum in Jiangsu province, China. Parasit Vectors 6, 138 (2013).

Clements, A. C., Firth, S., Dembele, R. & Garba, A. Use of Bayesian geostatistical prediction to estimate local variations in Schistosoma haematobium infection in West Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 87, 921–929 (2009).

Hu, Y. et al. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Schistosomiasis Japonica in Lake and Marshland Areas in China: The Effect of Snail Habitats. Am J Trop Med Hyg 91, 547–554 (2014).

Hu, Y. et al. Spatio-temporal Transmission and Environmental Determinants of Schistosomiasis Japonica in Anhui Province, China. PLos Negl Trop Dis 9, e0003470 (2015).

Cressie, N. & Wikle, C. K. Statistics for spatio-temporal data, xxii, 588 (Wiley, 2011).

Anderson, R. M. & May, R. M. Helminth infections of humans: mathematical models, population dynamics, and control. Adv Parasitol 24, 1–101 (1985).

Booth, M. et al. Micro-geographical variation in exposure to Schistosoma mansoni and malaria, and exacerbation of splenomegaly in Kenyan school-aged children. BMC Infect Dis 4, 13 (2004).

Wang, X. H. et al. Bayesian spatio-temporal modeling of Schistosoma japonicum prevalence data in the absence of a diagnostic ‘gold’ standard. PLos Negl Trop Dis 2, e250 (2008).

Yu, J. M., de Vlas, S. J., Jiang, Q. W. & Gryseels, B. Comparison of the Kato-Katz technique, hatching test and indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA) for the diagnosis of Schistosoma japonicum infection in China. Parasitol Int 56, 45–9 (2007).

Yang, G. J., Vounatsou, P., Zhou, X. N., Tanner, M. & Utzinger, J. A Bayesian-based approach for spatio-temporal modeling of county level prevalence of Schistosoma japonicum infection in Jiangsu province, China. Int J Parasitol 35, 155–62 (2005).

Clements, A. C. et al. A comparative study of the spatial distribution of schistosomiasis in Mali in 1984–1989 and 2004–2006. PLos Negl Trop Dis 3, e431 (2009).

Hu, Y. et al. Spatial pattern of schistosomiasis in Xingzi, Jiangxi Province, China: the effects of environmental factors. Parasit Vectors 6, 214 (2013).

Ridout, M., Demetrio, C. G. & Hinde, J. Models for count data with many zeros. in Proceedings of the XIX International Biometric Conference (Cape Town, South Africa, 1998).

Cressie, N. & Kapat, P. Some diagnostics for Markov random fields. J Comp Graph Stat 17, 726–49 (2008).

Mugglin, A. S., Cressie, N. & Gemmell, I. Hierarchical statistical modelling of influenza epidemic dynamics in space and time. Stat Med 21, 2703–21 (2002).

Rue, H. V. & Martino, S. Approximate Bayesian inference for hierarchical Gaussian Markov random field models. J Stat Plan Infer 137, 3177–3192 (2007).

Ruiz-Cárdenas, R., Krainski, E. T. & Rue, H. V. Direct fitting of dynamic models using integrated nested Laplace approximations — INLA. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 56, 1808–1828 (2012).

Blangiardo, M., Cameletti, M., Baio, G. & Rue, H. Spatial and spatio-temporal models with R-INLA. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol 4, 33–49 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Foundation for the Author of National Excellent Doctoral Dissertation of PR China (FANEDD) [grants number: 201186], the Talent Programs for Fostering Outstanding Youth of Shanghai [grants number: XYQ2013071], the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 81325017), Chang Jiang Scholars Program (No. T2014089), and Dr. Hu’s China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [grants number: 2014M560291].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J.Z. and Q.J.W. conceived the study; F.H.G., Q.Z.W. and S.Q.Z. performed the field collections; Y.H. and M.P.W. wrote the manuscript; Y.H., C.X., R.L., L.Q.S., H.L. and C.L.X. performed statistical analyses; all the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Ward, M., Xia, C. et al. Monitoring schistosomiasis risk in East China over space and time using a Bayesian hierarchical modeling approach. Sci Rep 6, 24173 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24173

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24173

This article is cited by

-

Influence of urbanization on schistosomiasis infection risk in Anhui Province based on sixteen year's longitudinal surveillance data: a spatio-temporal modelling study

Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2023)

-

Identification of the high-risk area for schistosomiasis transmission in China based on information value and machine learning: a newly data-driven modeling attempt

Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2021)

-

Non-communicable diseases are key to further narrow gender gap in life expectancy in Shanghai, China

BMC Public Health (2020)

-

Modeling schistosomiasis spatial risk dynamics over time in Rwanda using zero-inflated Poisson regression

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Understanding the rapid increase in life expectancy in shanghai, China: a population-based retrospective analysis

BMC Public Health (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.