Abstract

We reported the first observation of the two-photon-induced quantum cutting phenomenon in a Gd3+/Tb3+-codoped glass in which two photons at ~400 nm are simultaneously absorbed, leading to the cascade emission of three photons in the visible spectral region. The two-photon absorption induced by femtosecond laser pulses allows the excitation of the energy states in Gd3+ which are inactive for single-photon excitation and enables the observation of many new electric transitions which are invisible in the single-photon-induced luminescence. The competition between the two-photon-induced photon cascade emission and the single-photon-induced emission was manipulated to control the luminescence color of the glass. We demonstrated the change of the luminescence color from red to yellow and eventually to green by varying either the excitation wavelength or the excitation power density.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The phenomenon of photon cascade emission or the so called “quantum cutting”, in which a photon of high energy is absorbed and converted to two or more photons with lower energies, has been studied intensively in the past few decades because of its potential applications in mercury-free lamps and plasma display panels1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. In recent years, this phenomenon has drawn great attention in the research and development of high-efficiency solar cells because it can significantly improve the conversion efficiency of photon to electricity and reduce heat generation10,11,12,13. Owing to their unique energy states, rare-earth ions, especially the lanthanide ions, are considered as promising candidates not only for photon up-conversion but also for photon down-conversion13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. For example, solid state full color display23 has been demonstrated by exploiting the photon up-conversion in three lanthanide ions of Pr3+, Er3+ and Tm3+. In addition, the lanthanide ions have exhibited fascinating luminescent properties such as intense narrow-band emission, high conversion efficiency, broad emission peaks, much different lifetimes and good thermal stability8,21,24,25,26,27. Therefore, rare-earth-ion-doped materials have been widely studied and exhibited potential application in the fields of illumination, imaging, display, solar cells and medical radiology because such materials can be fabricated at a low cost and in large quantities23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

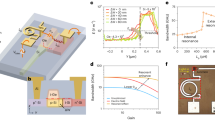

In rare-earth-ion-doped materials, Tb3+-doped glasses have been the focus of many studies because of their high luminescence efficiency at around 550 nm which is convenient for direct coupling with silicon detectors45. More interestingly, it has been shown that the luminescence can be further enhanced by adding Gd3+ into Tb3+-doped glasses because of the energy transfer (ET) from Gd3+ to Tb3+, as schematically shown in Fig. 1. In fact, the ET between Gd3+ and Tb3+ has been extensively investigated in many other different host materials46,47,48,49,50. Although electrons can be generated in Gd3+, the luminescence from Gd3+/Tb3+-codoped glasses arises mainly from the transitions from the level 5D4 to the levels 7F0–6 in Tb3+ which give rise to four emission bands in the visible light region46,47,48,49,50. In Fig. 1, it is noticed that the levels 6GJ in Gd3+ are located well above the high-energy levels in Tb3+ (5K7 etc.) while the levels 6DJ, 6IJ and 6PJ in Gd3+ have similar energies with some energy levels in Tb3+. If the population of the levels 6GJ in Gd3+ is induced, one can expect the transitions of electrons to the low-energy levels (6DJ, 6IJ and 6PJ) of Gd3+, the ET of electrons from Gd3+ to Tb3+, the transitions of electrons to the level 5D4 and finally to the levels 7F0–6. Such a cascade transition process may result in the cascade emission of photons with different energies. In practice, the population of the levels 6GJ in Gd3+ can be realized by using femtosecond (fs) laser light at ~400 nm through two-photon-induced absorption (TPA). The high peak power and wide linewidth of fs laser light are highly suitable for effectively exciting the levels 6GJ in Gd3+. Actually, fs laser light at 800 nm has been used to excite the three-photon-induced luminescence in rare-earth-ion-doped glasses37. When fs laser light at 400 nm is used to excite the levels 6GJ in Gd3+, the level 5D3 in Tb3+ with a wavenumber of ~26336 cm−1 (corresponding to a wavelength of ~381 nm) can also be populated through Rabi oscillation or phonon-assisted transition51, leading to the conventional emission from Tb3+. For excitation wavelengths (λex) shorter than 400 nm, the population probability for the levels 6GJ is reduced while that for the level 5D3 is increased. It implies the existence of a competition between the cascade emission and conventional emission that depends strongly on λex. On the other hand, the population of the level 5D3, which is caused mainly by Rabi oscillation51, will exhibit a strong dependence on the excitation power density (Pex). Therefore, it is expected that one can manipulate the competition between the cascade emission and conventional emission and thus control the luminescence color by varying λex or Pex, exploring its applications in color display52.

Results and Discussion

The proposed scheme was examined by using different glasses codoped with Gd3+ and Tb3+ and the dependence of luminescence color on λex and Pex was found to be a popular phenomenon (details in Supplementary Information, see Fig. S1). However, this behavior also exhibits a dependence on the concentration of Gd3+ and glass matrix. While the concentration of Gd3+ determines the photon cascade emission, the glass matrix affects the phonon-assisted processes such as the nonradiative decay or the relaxation of electrons. In this work, we show a pronounced phenomenon observed in a silicate glass with a composition of 56SiO2-10Al2O3-12Li2O-20Gd2O3-2Tb2O3 (mol%). The ET from Gd3+ to Tb3+ was also observed in this glass (details in Supplementary Information, see Section 4).

In order to see the λex-dependent competition, we varied λex from 375 to 405 nm and examined the luminescence of the glass. For λex ≤ 390 nm, the luminescence always appeared to be green. However, the luminescence was changed from green to yellow when λex was slightly shifted from 390 to 392 nm. More surprisingly, the luminescence turned to be red when λex was further shifted to 394 nm. A comparison of the emission spectra under different λex of 390, 392 and 394 nm is presented in Fig. 2. The photos for the excitation spot are shown in the insets. It can be seen that the emission spectrum at λex = 390 nm is dominated by the emission band at ~540 nm which corresponds to green color. For λex = 392 nm, the relative intensities of the emission bands at ~580 nm and ~622 nm, which correspond to yellow and red colors, increase rapidly. A close inspection reveals that the peak of the emission band at ~622 nm is blue-shifted to ~613 nm. In addition, two new emission bands emerge at ~654 nm and ~704 nm, contributing to red color. For λex = 394 nm, the intensity of the emission band at ~613 nm exceeds that of the emission band at ~550 nm and the relative intensities of the emission bands at ~654 and 704 nm are further increased, turning the color of the luminescence into red. In previous reports, the luminescence of Tb3+-doped and Gd3+/Tb3+-codoped glasses originates mainly from the electronic transitions from the level 5D4 to the levels 7F0–6 and appears to be green. There is no report on the observation of yellow or red luminescence. Here, it is interesting that the color change in the luminescence occurs in a narrow wavelength region of 390−394 nm, which is comparable to the linewidth of the fs laser pulses (~4.0 nm).

In order to understand the underlying physical mechanism, we examined the evolution of the emission spectrum and the luminescence color with increasing Pex for different λex, as shown in Fig. 3a–c. The dependence of the luminescence intensities for different emission bands on Pex was also extracted, as shown in Fig. 3d–f. For λex = 390 nm, the luminescence color appeared to be green and remained unchanged with increasing Pex. It can be seen that the intensities of the four major emission bands, which are centered at 488, 544, 585 and 622 nm, increased almost with the same rate. Consequently, the emission spectrum remained nearly unchanged except the absolute intensity. The fitting of the Pex dependence of the luminescence intensity gives nearly the same slope of ~1.0 for all the emission bands, indicating that the emission is governed by single-photon process. The situation was changed for λex = 392 nm. Two new emission bands emerged at 654 and 704 nm and the emission band peaking originally at 622 nm was blue-shifted to 613 nm. The electronic transitions related to the new emission bands (details in Supplementary Information, see Table I), which are attributed to the transitions between the high-energy levels of Gd3+, were previously observed in other materials53,54 doped with Gd3+ under single-photon excitation. For comparison, the glasses doped with only Gd3+ or Tb3+ were also examined under the same condition (details in Supplementary Information, see Figs S3 and S5). The slopes for the emissions bands at 488, 544 and 585 nm remained unchanged while smaller slopes were observed for the two new emission bands and the emission band at 613 nm. The change in the emission spectrum was negligible and the luminescence color remained to be yellow with increasing Pex. For λex = 394 nm, the dependence of the emission spectrum on Pex became significant. It is noticed that the intensities of the emission bands at 488 and 544 nm increased in greater rates and the center of the excitation spot became yellow at high Pex, as evidenced in the larger slopes of ~1.40. This behavior indicates that two-photon process has been involved in the emission process.

Evolution of the emission spectrum and the luminescence color of the glass with increasing Pex under different λex of (a) 390 nm, (b) 392 nm and (c) 394 nm. The dependence of the luminescence intensities for different emission bands on Pex and the fitting for the experimental data are presented in (d–f) for λex of 390, 392 and 394 nm, respectively.

As mentioned above, the effective population of the levels 6GJ can be realized by simultaneously absorbing two photons at 400 nm. For λex = 390 nm, the population of the levels 6GJ through TPA can be neglected because of the large energy mismatch. As λex is red-shifted toward 400 nm, an increase in the population probability is expected. In Fig. 4, we present the evolution of the emission spectrum and the luminescence color with increasing Pex measured for λex = 400 and 405 nm. For λex = 400 nm, the emission spectrum was similar to that observed at λex = 394 nm. However, it is noticed that the intensity of the emission band at 613 nm became stronger than that of the emission band at 544 nm and the luminescence appeared to be red at low Pex. At high Pex, the intensity of the latter exceeded that of the former, changing the luminescence color to green, as shown in the inset of Fig. 4a. This behavior is also reflected in the Pex dependence of the luminescence intensity shown in Fig. 4c. The slopes for the emission bands at 488 and 544 nm obtained by fitting the experimental data (1.59 and 1.64) were much larger than those for the emission bands at 590, 613, 654 and 704 nm whose slopes are reduced by nonradiative decay (details in Supplementary Information, see Fig. S6). For λex = 405 nm, the emission spectrum was changed remarkably because of the emergence of many new emission bands, as shown in Fig. 4b. In this case, the red luminescence observed at low Pex evolved gradually into green one with increasing Pex, similar to that observed at λex = 400 nm. In comparison, the slopes for the emission bands at 488 and 544 nm were reduced slightly to ~1.50 because the TPA process at λex = 405 nm is not as efficient as that at λex = 400 nm.

Evolution of the emission spectrum and the luminescence color of the glass with increasing Pex under different λex of (a) 400 nm and (b) 405 nm. The dependence of the luminescence intensities for different emission bands on Pex and the fitting for the experimental data are presented in (c,d) for λex of 400 and 405 nm, respectively.

Based on the theory of colorimetry (details in the Supplementary Information, see Section 7), one can easily deduce the chromaticity coordinates for the luminescence observed under different excitation conditions and the results are shown in Fig. 5. From the Fig. 5a, under low Pex, we can see that the chromaticity coordinates for λex = 390, 392 and 394 nm appear in the green, yellow and red regions, respectively. In all cases, a shift of the chromaticity coordinate with increasing Pex is found and it becomes larger for longer λex. The largest shift of the chromaticity coordinate is observed at λex = 400 nm, as shown in Fig. 5b. In this case, the luminescence color is changed from red to yellow and eventually to green with increasing Pex.

When the levels 6GJ in Gd3+ are effectively populated, the photon cascade emission is expected to dominate the emission process. It is clearly reflected in the new emission bands which correspond to the photons emitted in the cascade transition of electrons between the energy levels of Gd3+ and Tb3+. In Fig. 6, we present a comparison of the emission spectra obtained at different λex of 390, 392, 394, 400 and 405 nm in a logarithmic coordinate where the new emission bands originating from the photon cascade emission can be readily identified at λex = 400 and 405 nm and indicated by arrows. In most cases, the cascade emission of three photons is observed, as shown in Fig. 1. The first photon is generated by the transition of electrons between the levels of 6GJ and 6IJ (or 6PJ) in Gd3+. The wavelengths of the emission photons range from 571 to 704 nm, contributing yellow or red color. The transition from the levels 6GJ to 6DJ in Gd3+ is thought to be nonradiative53,54. The emission of the first photon is followed by an ET process of electrons from Gd3+ to Tb3+. Then, the emission of the second photon occurs through the transitions of electrons between the levels 5H3, 5F4,2,1, 5I6,4, 5K8 and the level 5D3 or 5D4. During this process, the wavelengths of the emission photons cover a broad wavelength range of 495 to 690 nm, contributing mainly yellow and red colors. The emission of the last photon occurs mainly between the levels 5D4 (5D3) and 7F6,5,4,3, contributing to green color. Although the intensities are quite weak, one can identify the new emission bands at 421, 438 and 460 which can be assigned to the transitions between the levels 5D3 and 7F5,4,3.

Having understood the photon cascade emission, one can easily understand the luminescence color change induced by varying λex and Pex. For λex < 392 nm, the levels 6GJ are not populated effectively and the photon cascade emission is not initiated. In this case, the population of the levels 5D3 and 5D4 in Tb3+ through Rabi oscillation or phonon assistance is dominant, giving rise to the four emission bands and green luminescence. For λex > 392 nm, the electrons begin to occupy the levels 6GJ, initiating the photon cascade emission which competes with the conventional emission. When the emission process becomes dominated by the photon cascade emission, the luminescence appears to be yellow or red. With increasing Pex, the population of the level 5D3 becomes significant because of two reasons. First, the population probability due to Rabi oscillation increases with increasing Pex. Second, more electrons relax from the levels 6GJ to the level 5D3 after emitting two photons. Therefore, a rapid increase in the intensities of the emission bands at 488 and 544 nm is observed, turning the luminescence into yellow and green at high Pex. In our case, it was found that the efficiency of the two-photon-induced transitions and ET process from Gd3+ to Tb3+ depends strongly on the concentrations of Gd3+ and Tb3+ because it is proportional to the inverse sixth power of the distance between the two types of ions (details in the Supplementary Information, see Section 5). In this work, we have compared the tunable range of the luminescence color by varying λex and Pex for several glass samples with different concentrations of Gd3+ and found that the best performance was achieved in the glass with the largest concentration of Gd3+.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have observed the two-photon-induced photon cascade emission in a glass codoped with Gd3+ and Tb3+ by using fs laser pulses. By varying either λex or Pex, we have demonstrated the manipulation of the luminescence color through the competition between the photon cascade emission and conventional emission. Many new emission bands, which are not usually observed in the traditional luminescence of Tb3+-doped or Gd3+/Tb3+-codoped materials have been clearly revealed in the emission spectrum when the photon cascade emission is dominant. More importantly, the dependence of the luminescence on both λex and Pex implies potential applications in laser-induced color display.

Methods

Materials Preparation

The silicate glass was prepared through melting the mixture of analytical reagents of SiO2, Al(OH)3, Li2CO3, Gd2O3 and Tb4O7 at 1600 °C for 30 minutes. The melt was then poured onto a preheated (200 °C) stainless steel plate and annealed at 500 °C for 2 hours. The synthetized glass was cut into 10 × 10 × 1 mm3 sheets and polished for optical measurements.

Photonluminescence Measurements

In our experiments, the fs laser light with a repetition rate of 76 MHz and a pulse duration of ~130 fs delivered by a Ti: sapphire oscillator (Mira 900S, Coherent) was introduced into a harmonic generator (Harmonics 9300, Coherent) and the output light with a tunable wavelength from 375 to 405 nm was employed to excite the glass. The excitation intensity was characterized by the peak power density of the fs laser pulses. It was introduced into an inverted microscope (Observer A1, Zeiss) and focused on the glass by using a 60 × objective lens (NA = 0.85). The diameter of the excitation spot was estimated to be ~4.0 μm. The luminescence generated by the glass was collected by the same objective lens and delivered to a spectrometer (SR-500I-B1, Andor) equipped with a charge-coupled device (CCD) (DU970N, Andor) for analysis. The photos of the excitation spot were taken by using a camera from the eyepiece of the microscope.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yuan, M.-H. et al. Controlling the Two-Photon-Induced Photon Cascade Emission in a Gd3+/Tb3+-Codoped Glass for Multicolor Display. Sci. Rep. 6, 21091; doi: 10.1038/srep21091 (2016).

References

Wegh, R. T., Donker, H., Oskam, K. D. & Meijerink, A. Visible quantum cutting in LiGdF4:Eu3+ through downconversion. Science 283, 663–666 (1999).

Kubota, S. & Shimada, M. Sr3Al10SiO20:Eu2+ as a blue luminescent material for plasma displays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 2749–2751 (2002).

Pust, P. et al. Narrow-band red-emitting Sr[LiAl3N4]:Eu2+ as a next-generation LED-phosphor material. Nat. Mater. 13, 891–896 (2014).

Ghosh, P., Tang, S. & Mudring, A. V. Efficient quantum cutting in hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanorods. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 8640–8644 (2011).

Lorbeer, C. & Mudring, A. V. Quantum cutting in nanoparticles producing two green photons. Chem. Commun. 50, 13282–13284 (2014).

Lorbeer, C., Cybinska, J. & Mudring, A. V. Facile preparation of quantum cutting GdF3:Eu3+ nanoparticles from ionic liquids. Chem. Commun. 46, 571–573 (2010).

Lorbeer, C., Cybinska, J. & Mudring, A. V. Reaching quantum yields » 100% in nanomaterials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 1862–1868 (2014).

Zhang, Q. Y. & Huang, X. Y. Recent progress in quantum cutting phosphors. Prog. Mater. Sci. 55, 353–427 (2010).

Fan, B., Chlique, C., Merdrignac-Conanec, O., Zhang, X. & Fan, X. Near-infrared quantum cutting material Er3+/Yb3+ doped La2O2S with an external quantum yield higher than 100%. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 11652–11657 (2012).

Timmerman, D., Izeddin, I., Stallinga, P., Yassievich, I. N. & Gregorkiewicz, T. Space-separated quantum cutting with silicon nanocrystals for photovoltaic applications. Nat. Photonics 2, 105–109 (2008).

van der Ende, B. M., Aarts, L. & Meijerink, A. Near-infrared quantum cutting for photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 21, 3073–3077 (2009).

van der Ende, B. M., Aarts, L. & Meijerink, A. Lanthanide ions as spectral converters for solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11, 11081–11095 (2009).

Meijer, J. M. et al. Downconversion for solar cells in YF3:Nd3+, Yb3+. Phys. Rev. B 81, 035107 (2010).

Xu. Y. et al. Efficient near-infrared down-conversion in Pr3+-Yb3+ codoped glasses and glass ceramics containing LaF3 nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 13056–13062 (2011).

Heer, S., Lehmann, O., Haase, M. & Güdel, H. U. Blue, green and red upconversion emission from lanthanide-doped LuPO4 and YbPO4 nanocrystals in a transparent colloidal solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 3179–3182 (2003).

Vetrone, F., Mahalingam, V. & Capobianco, J. A. Near-infrared-to-blue upconversion in colloidal BaYF5:Tm3+, Yb3+ nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 21, 1847–1851 (2009).

Mauser, N. et al. Tip enhancement of upconversion photoluminescence from rare earth ion doped nanocrystals. ACS Nano 9, 3617–3626 (2015).

Pichaandi, J., Boyer, J. C., Delaney, K. R. & van Veggel, F. C. J. M. Two-photon upconversion laser (scanning and wide-field) microscopy using Ln3+-doped NaYF4 upconverting nanocrystals: a critical evaluation of their performance and potential in bioimaging. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 19054–19064 (2011).

Chen, G., Ohulchanskyy, T. Y., Kumar, R., Ågren, H. & Prasad, P. N. Ultrasmall monodisperse NaYF4:Yb3+/Tm3+ nanocrystals with enhanced near-infrared to near-infrared upconversion photoluminescence. ACS Nano 4, 3163–3168 (2010).

Hua, R. et al. Visible quantum cutting in GdF3:Eu3+ nanocrystals via downconversion. Nanotechnology 17, 1642–1645 (2006).

Höppe, H. A. Recent developments in the field of inorganic phosphors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3572–3582 (2009).

Chen, G., Ohulchanskyy, T. Y., Kachynski, A., Ågren, H. & Prasad, P. N. Intense visible and near-infrared upconversion photoluminescence in colloidal LiYF4:Er3+ nanocrystals under excitation at 1490 nm. ACS Nano 5, 4981–4986 (2011).

Downing, E., Hesselink, L., Ralston, J. & Macfarlane, R. A three-color, solid-sate, three-dimensional display. Science 273, 1185–1189 (1996).

Blasse, G. & Grabmaier, B. C. Luminescent Materials. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1994).

Gai, S., Li, C., Yang, P. & Lin, J. Recent progress in rare earth micro/nanocrystals: soft chemical synthesis, luminescent properties and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 114, 2343–2389 (2014).

Zhou, J., Liu, Q., Feng, W., Sun, Y. & Li, F. Upconversion luminescent materials: advances and applications. Chem. Rev. 115, 395–465 (2015).

Liu, Y., Tu, D., Zhu, H. & Chen, X. Lanthanide-doped luminescent nanoprobes: controlled synthesis, optical spectroscopy and bioapplications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 6924–6958 (2013).

Nyk, M., Kumar, R., Ohulchanskyy, T. Y., Bergey, E. J. & Prasad. P. N. High contrast in vitro and in vivo photoluminescence bioimaging using near infrared to near infrared up-conversion in Tm3+ and Yb3+ doped fluoride nanophosphors. Nano Lett. 8, 3834–3838 (2008).

Sotiriou, G. A., Franco, D., Poulikakos, D. & Ferrari, A. Optically stable biocompatible flame-made SiO2-coated Y2O3:Tb3+ nanophosphors for cell imaging. ACS Nano 6, 3888–3897 (2012).

Chen, G. et al. (α-NaYbF4:Tm3+)/CaF2 core/shell nanoparticles with efficient near-infrared to near-infrared upconversion for high-contrast deep tissue bioimaging. ACS Nano 6, 8280–8287 (2012).

Bouzigues, C., Gacoin, T. & Alexandrou, A. Biological applications of rare-earth based nanoparticles. ACS Nano 5, 8488–8505 (2011).

Heer, S., Kömpe, k ., Güdel, H. U. & Haase, M. Highly efficient multicolour upconversion emission in transparent colloids of lanthanide-doped NaYF4 nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 16, 2102–2105 (2004).

Bünzli, J. C. G. Lanthanide luminescence for biomedical analyses and imaging. Chem. Rev. 110, 2729–2755 (2010).

Sudheendra, L. et al. NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles for enhanced X-ray excited optical imaging. Chem. Mater. 26, 1881–1888 (2014).

Damasco, J. A. et al. Size-tunable and monodisperse Tm3+/Gd3+-doped hexagonal NaYbF4 nanoparticles with engineered efficient near infrared-to-near infrared upconversion for in vivo imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 13884–13893 (2014).

Ronda, C. R. Phosphors for lamps and displays: an applicational view. J. Alloy. Comp. 225, 534–538 (1995).

Zhang, S., Zhu, B., Zhou, S., Xu, S. & Qiu, J. Multi-photon absorption upconversion luminescence of a Tb3+-doped glass excited by an infrared femtosecond laser. Opt. Express 15, 6883–6888 (2007).

Zanella, G. et al. A new cerium scintillating glass for X-ray detection. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 345, 198–201 (1994).

Eliseeva, S. V. et al. Multiphoton-excited luminescent lanthanide bioprobes: two- and three-photon cross sections of dipicolinate derivatives and binuclear helicates. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 2932–2937 (2010).

Zhou, S. S. et al. Synthesis, Optical properties and biological imaging of the rare earth complexes with curcumin and pyridine. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 22774–22780 (2012).

Bettinelli, M., Carlos, L. & Liu, X. A new class of nanomaterials that convert near-IR radiation into tunable visible light has important implications for many fields of science and technology. Phys. Today 68(9), 38–44 (2015).

Deng, R. et al. Temporal full-colour tuning through non-steady-state upconversion. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 237–242 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multicolor barcoding in a single upconversion crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4893–4896 (2014).

Meruga, J. M., Baride, A., Cross, W., Kellara, J. J. & May, P. S. Red-green-blue printing using luminescence-upconversion inks. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 2221–2227 (2014).

Nikl, M. Scintillation detectors for X-rays. Meas. Sci. Technol. 17, R37–R54 (2006).

Huang, S. & Gu, M. Enhanced luminescent properties of Tb3+ ions in transparent glass ceramics containing BaGdF5 nanocrystals. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 358, 77–80 (2012).

Reisfeld, R., Greenberg, E., Velapoldi, R. & Barnett, B. Luminescence quantum efficiency of Gd and Tb in borate glasses and the mechanism of energy transfer between them. J. Chem. Phys. 56, 1698–1705 (1972).

Raju, G. S. R. et al. Gd3+ sensitization effect on the luminescence properties of Tb3+ activated calcium gadolinium oxyapatite nanophosphors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, J20–J26 (2011).

Bril, A. & Wanmaker, W. L. Energy transfer in CaNaBO3 activated with Tb and Gd. J. Chem. Phys. 43, 2559–2560 (1965).

Han, B., Liang, H., Huang, Y., Tao, Y. & Su, Q. Vacuum ultraviolet-visible spectroscopic properties of Tb3+ in Li(Y, Gd)(PO3)4: tunable emission, quantum cutting and energy transfer. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 6770–6777 (2010).

Zhang, C. F. et al. Femtosecond pulse excited two-photon photoluminescence and second harmonic generation in ZnO nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 042117 (2006).

Li, G., Wang, W., Yang, W. & Wang, H. Epitaxial growth of group III-nitride films by pulsed laser deposition and their use in the development of LED devices. Surf. Sci. Rep. 70, 380–423 (2015).

Yang, Z., Lin, J. H., Su, M. Z., Tao, Y. & Wang, W. Photon cascade luminescence of Gd3+ in GdBaB9O16 . J. Alloy. Comp. 308, 94–97 (2000).

Wegh, R. T., Donker, H., Meijerink, A., Lamminmäki, R. J. & Hölsä, J. Vacuum-ultraviolet spectroscopy and quantum cutting for Gd3+ in LiYF4 . Phys. Rev. B 56, 13841–13848 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51171066, 11374109 and 11204092) and the Scientific Research Foundation of the Graduate School of South China Normal University (Grant No. 2015lkxm01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Lan and M.-H. Yuan conceived the idea. S.-L.Tie and Z.-M. Yang fabricated the glass samples. M.-H. Yuan, H.-H. Fan and H. Li carried out the optical experiments. S. Lan, M.-H. Yuan, S.-L. Tie and Z.-M. Yang analyzed the data. M.-H. Yuan and S. Lan wrote the manuscript. S. Lan and S.-L. Tie supervised the project. All the authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, MH., Fan, HH., Li, H. et al. Controlling the Two-Photon-Induced Photon Cascade Emission in a Gd3+/Tb3+-Codoped Glass for Multicolor Display. Sci Rep 6, 21091 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21091

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21091

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

and the single photon absorption assisted by Rabi oscillation or phonons

and the single photon absorption assisted by Rabi oscillation or phonons  and the possible electronic transitions between the energy levels are illustrated.

and the possible electronic transitions between the energy levels are illustrated.