Abstract

Anopheles gambiae s.s. mosquitoes are efficient vectors for Plasmodium falciparum, although variation exists in their susceptibility to infection. This variation depends partly on the thioester-containing protein 1 (TEP1) and TEP depletion results in significantly elevated numbers of oocysts in susceptible and resistant mosquitoes. Polymorphism in the Plasmodium gene coding for the surface protein Pfs47 modulates resistance of some parasite laboratory strains to TEP1-mediated killing. Here, we examined resistance of P. falciparum isolates of African origin (NF54, NF165 and NF166) to TEP1-mediated killing in a susceptible Ngousso and a refractory L3–5 strain of A. gambiae. All parasite clones successfully developed in susceptible mosquitoes with limited evidence for an impact of TEP1 on transmission efficiency. In contrast, NF166 and NF165 oocyst densities were strongly reduced in refractory mosquitoes and TEP1 silencing significantly increased oocyst densities. Our results reveal differences between African P. falciparum strains in their capacity to evade TEP1-mediated killing in resistant mosquitoes. There was no significant correlation between Pfs47 genotype and resistance of a given P. falciparum isolate for TEP1 killing. These data suggest that polymorphisms in this locus are not the sole mediators of immune evasion of African malaria parasites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria is one of the most important infectious diseases worldwide with an estimated 198 million cases and 584,000 deaths annually1. The responsible Plasmodium protozoan parasites undergo a complex sporogonic life cycle once ingested by female Anopheles mosquitoes from an infected human host. Male and female gametocytes are taken up and fuse to form a motile ookinete. The ookinete then penetrates the mosquito midgut epithelium to establish infection in the basal labyrinth where it is exposed to soluble immune factors secreted by mosquito blood cells. Surviving ookinetes settle under the basal lamina to differentiate into an oocyst that matures over time and eventually ruptures to release thousands of sporozoites that invade the salivary glands and render the mosquito infectious for humans2.

A. gambiae from the field3,4 or the lab5,6 show variable susceptibility to Plasmodium parasites, which may be partly attributed to the efficiency of mosquito immune factors to kill ookinetes7,8,9. The immune response is mediated by a series of genes whose expression is induced by such stimuli as blood feeding, infection with bacteria and/or Plasmodium parasites and sterile wounding10.

REL111,12,13 and REL214,15,16 together with Jak/Stat17 and JNK18,19 are the four major mosquito immune signaling pathways. Thioester-containing protein 1 (TEP1) is regulated by REL1, REL2 and JNK pathways, reflecting its central importance in mosquito immune responses10. TEP1 is secreted by hemocytes into the hemolymph and its activity is controlled by a complex consisting of two leucine-rich repeat (LRR) proteins, LRIM and APL1C. The LRR complex maintains circulation of the activated form of TEP1 in the hemolymph15,20. Binding of TEP1 to the surface of invading ookinetes initiates near total lysis of the concomitant parasite population21. Knockdown of TEP1 in the A. gambiae - Plasmodium berghei laboratory model results in a 3- to 5-fold increase in oocyst numbers in susceptible and resistant mosquitoes21,22. Depending on the parasite genetic composition, TEP1 also mediates P. falciparum ookinete killing in A. gambiae mosquitoes7.

The refractory A. gambiae L3–5 (or R) strain was initially selected from the susceptible G3 (S) strain for its high resistance phenotype for several Plasmodium species5,23. In the L3–5 strain, the majority of tested parasite species are killed and melanized within the first two days after infectious blood feeding. Interestingly, silencing of the members of the complement-like system, including TEP1, LRRs and NOX5/HPX2, renders these resistant mosquitoes fully susceptible to infections with P. berghei, demonstrating the key role in this defense mechanism. Moreover, polymorphism at the TEP1 locus is directly responsible for the differences between R and S strains in P. berghei killing; R strain is homozygous for TEP1*R1 allele, whereas S strains contain TEP1*S1/S2/R2 alleles24. Although all alleles confer variable degrees of resistance to malaria parasites, TEP1*R1 confers the highest levels of resistance22.

Recent reports revealed differences in sporogonic development between African (NF54, GB4) and Brazilian (7 G8) P. falciparum laboratory strains in R mosquitoes, where NF54 was resistant to TEP1 mediated killing, while 7 G8 was highly susceptible7,25. Based on these results, it was suggested that sympatric African parasites may have developed means to evade TEP1 killing25. Interestingly, resistance of the parasites to TEP1 correlated with the polymorphism in the Pfs47 gene encoding a cysteine-rich gametocyte surface protein. In A. gambiae, infections with the Pfs47KO strain were completely aborted by the mosquito complement-like system26, suggesting that both mosquito and parasite genetic factors contribute to the outcome of infections. An elegant evolutionary hypothesis was put forward suggesting that polymorphism at the Pfs47 locus permitted adaptation of African parasites to the mosquito complement-like system26. These conclusions, however, were based on studies with a single laboratory NF54 strain of likely African origin that has been maintained in the culture for more than 30 years.

Here we examined whether variation at the Pfs47 locus correlates with the sensitivity of different African P. falciparum strains to TEP1 mediated killing. We report that two new P. falciparum strains NF165 (originating from Malawi) and NF166 (originating from Guinea) differ in their resistance to TEP1-mediated killing. Genotyping Pfs47 in a series of African P. falciparum parasites demonstrate that variability in Pfs47 does not correlate with resistance to TEP1-dependent ookinete killing. Sequence comparison revealed striking divergence between Pfs47 genotype in NF54 (and its relative 3D7) and other African P. falciparum isolates, suggesting that currently circulating P. falciparum isolates may be more susceptible to TEP1-mediated killing than initially thought.

Results

Resistance of P. falciparum strains to TEP1-mediated killing in susceptible A. gambiae

We first examined the susceptibility of the recently colonized Ngousso mosquitoes to P. falciparum NF54 strain and two freshly isolated strains: NF165 (Malawi) and NF166 (Guinea). Ngousso strain is a mix of TEP1*S alleles (0,7 - *S1/S1; 0,2 - *S1/S2; 0,1 - *S2/S2) and has been widely used for experimental infections in Cameroon27. Young females were injected with dsRNA to silence expression of TEP1, whereas noninjected mosquitoes and mosquitoes injected with dsRNA of an unrelated gene (dsLacZ) served as controls. Efficiency of TEP1 silencing was evaluated by immunoblotting of the hemolymph extracts collected from dsLacZ and dsTEP1 mosquitoes four days after injection (Fig. S1). Two experiments with P. berghei infected mice confirmed that TEP1 silencing was efficient as it caused a significant increase in oocyst numbers in the dsTEP1 as compared to dsLacZ mosquitoes (Fig. S2).

In parallel, injected mosquitoes were fed on a membrane feeder system containing P. falciparum gametocyte culture. At least three independent infections were performed with P. falciparum strains NF54, NF166 and NF165. We compared oocyst numbers in noninjected and injected mosquitoes and observed a significant effect of wounding on infections with all three tested P. falciparum strains (Table S1 and Fig. 1A–C). In line with the previous reports for NF54, no increase in oocyst numbers was observed in dsTEP1 as compared to control dsLacZ mosquitoes (p = 0.30; Table 1 and Fig. 1A). Similarly, TEP1 silencing did not affect development of NF166 (p = 0.25, Table 1 and Fig. 1B). A statistically significant 1.7-fold increase in oocyst burden after TEP1 knockdown was detected for NF165 (p < 0.001, 95% CI 1.32–2.19, Table 1 and Fig. 1C). These results suggest that P. falciparum clones of African origin differ in their susceptibility to TEP1-mediated killing in a susceptible A. gambiae strain.

Effect of TEP1 silencing and wounding in A. gambiae S mosquitoes on P. falciparum (strain NF54, NF166 and NF165) infection.

Female mosquitoes were injected with dsLacZ (control) or dsTEP1 4 days prior to feeding on a P. falciparum gametocyte mixture. Oocysts were visualized on day 7–8 post infection (p.i.) by mercurochrome staining of midguts and counted by microscopy. (A) Effect of wounding and TEP1 silencing for P. falciparum NF54. (B) Effect of wounding and TEP1 silencing for P. falciparum NF166. (C) Effect of wounding and TEP1 silencing for P. falciparum NF165. Data shown of individual experiments, for all strains phenotypes were confirmed in at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was done on pooled experiments and significance between groups are indicated: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (negative binomial regression model).

Resistance of P. falciparum strains to TEP1-mediated killing in resistant A. gambiae

We determined the degree of resistance of the L3–5 mosquitoes to infection with P. falciparum isolates and assessed the contribution of the complement-like factor TEP1 to this resistance. To this end, dsLacZ and dsTEP1 were injected into the thorax of young R females, whereas noninjected mosquitoes served as a control. Four days after injection, hemolymph of dsLacZ and dsTEP1 injected mosquitoes was collected and immunoblotting analysis was performed to evaluate efficiency of TEP1 silencing at the protein level (Fig. S3). As described above, two independent infections with P. berghei parasites confirmed the functional efficiency of TEP1 depletion. Ookinete development was almost completely aborted in the dsLacZ group and melanized parasites were observed in the mosquito midguts. As expected, TEP1 silencing significantly increased oocyst numbers and completely inhibited melanization. (Fig. S4).

In parallel, injected mosquitoes were fed on a membrane feeder system containing P. falciparum gametocytes. We performed three independent infections of L3–5 mosquitoes with the P. falciparum isolates. Overall infection levels were statistically significant lower in L3–5 than in Ngousso. Wounding by microinjection had a statistically significant effect on parasite development for NF54 and NF165. This wounding effect was not observed for NF166 (Table S1 and Fig. 2A). We then compared the development of the three parasite clones in the presence and absence of TEP1. As reported previously, silencing of TEP1 had no effect on NF54 survival and did not restore the lower infection burden resulting from wounding, suggesting a TEP1-independent mechanism of ookinete killing. In contrast to NF54, TEP1 silencing in L3–5 mosquitoes significantly increased oocyst loads of two other strains: 3.6-fold for NF165 (95% CI 2.36–5.39, p < 0.001) and 1.8-fold for NF166 (95% CI 1.31–2.40, p < 0.001) (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Strikingly, variable numbers of melanized ookinetes were detected in infections with all tested parasite strains. Melanized ookinetes were most commonly observed in NF165 infections (up to 66%), followed by in NF54 (12%) and NF166 (4%). TEP1 silencing completely abolished ookinete melanization in all three strains, suggesting a key role of the complement-like molecule in this defense mechanism (Fig. 2B,C).

Effect of wounding and of TEP1 silencing on development of P. falciparum (NF54, NF166 and NF165 439 strains) in A. gambiae R mosquitoes.

Female mosquitoes were injected with dsLacZ (control) or dsTEP1 4 days 440 prior to feeding on a P. falciparum gametocyte mixture. Oocysts were visualized on day 7–8 p.i. by 441 mercurochrome staining of midguts and counted by microscopy. (A) Comparison of P. falciparum live oocyst 442 counts between control groups (none vs. dsLacZ) for effect of wounding and between dsLacZ injected and TEP1 443 silenced group. (B) Numbers of live and melanized oocyst on individual midguts in the control injected group. 444 Proportion of live/melanized is depicted in the pie chart. (C) Numbers of live and melanized oocysts on 445 individual midguts after TEP1 silencing. Proportion of live/melanized is depicted in the pie chart. Data shown of 446 individual experiments, for all strains phenotypes were confirmed in at least three independent experiments. 447 Statistical analysis was done on pooled experiments and significance between groups are indicated: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (negative binomial regression model).

Taken together, these results suggest that African P. falciparum strains, including NF54, do not evade mosquito immune responses completely and suffer significant losses in terms of successful oocyst formation. Moreover, the efficiency of the mosquito immune responses depends on the genetic background of the mosquito and of the parasite. While all examined Plasmodium isolates suffer substantial losses in R mosquitoes, TEP1 mediates killing of NF165 and, to a lesser extent, NF166 isolates. As silencing of TEP1 fails to rescue killing of NF54 parasites in R mosquitoes, we suggest that TEP1-resistant parasite isolates are eliminated by currently uncharacterized immune responses.

We conclude that African P. falciparum strains vary in their susceptibility to TEP1-mediated killing and that the outcome of infection depends on the combination of genetic backgrounds of both mosquitoes and parasites.

Pfs47 polymorphism in P. falciparum isolates from Africa

To examine whether Pfs47 polymorphism determines the outcome of infections with natural P. falciparum isolates, we explored genetic diversity in the immune-variable region that was proposed to underlie complement susceptibility of African P. falciparum strains26. To this end, the region of interest of Pfs47 was PCR-amplified and sequenced from the NF54, NF165 and NF166 strains and from field isolates from Cameroon27. In addition, we compared Pfs47 sequences of laboratory and field P. falciparum isolates of diverse geographic origins available in the public databases (MalariaGen project, PlasmoDB). The Pfs47 sequences of NF166 and NF165 displayed strong similarities with other African strains (S2 Table) but were markedly different from parasite strains from Latin America and South-East Asia and our reference P. falciparum strains (NF54 and 3D7). For example, Pfs47 sequences of P. falciparum 7G8 (Latin America, highly susceptible) and NF135 (South-East Asia) displayed three unique SNPs compared to all strains originated from sub Saharan Africa (S2 Table).

Regardless of origin, C581A−>P194H polymorphism was fixed in all 26 Pfs47 sequences, except for the reference strains NF54 and 3D7 and a mixed isolate MA7 from Cameroon, which was heterozygous for C/A (S2 Table). Interestingly, this was the only SNP that distinguished the most TEP1-sensitive P. falciparum strain identified in this study NF165 from the TEP1-evasive NF54. The NF166 strain was more divergent from NF54/3D7 and in addition to C581A, displayed three additional missense SNPs (G657A−>M219I; A742T−>I248L, A814T−>N272Y). Sequenced isolates from Cameroon were very similar to those of NF165 and NF166 showing no correlation between Pfs47 genotype and resistance to TEP1-mediated killing. Indeed, six out of 10 potentially “susceptible” genotypes of NF165-type were resistant to TEP1 killing in S mosquitoes. Conversely, two potentially “resistant” NF166-type genotypes were susceptible to TEP1 (S2 Table).

As no significant correlation between resistance of a given P. falciparum isolate to TEP1 killing and Pfs47 genotype was detected, we concluded that polymorphism at this locus alone does not account for variation in TEP1-mediated immune evasion of African malaria parasites. Our results further suggest that the laboratory 3D7 and NF54 strains represent an exception, rather than a rule in regard to common Pfs47 variants and cannot be considered to be representative of other P. falciparum isolates from Africa in this context.

Discussion

Molecular mechanisms of mosquito immune responses to P. falciparum infection and of parasite immune-evasion strategies are important for our understanding of malaria transmission dynamics. It has been suggested that the high disease burden in Africa may be (partly) attributed to the parasite adaptation of African P. falciparum strains to their sympatric vector through evasion of TEP1-mediated killing25. We present evidence that parasite populations in sub Saharan Africa differ in their ability to effectively evade TEP1 effector functions and that these differences in susceptibility are most pronounced in the resistant strain of A. gambiae.

The reason for variation in susceptibility of P. falciparum isolates to TEP1-mediated killing is currently unknown. Although mosquito populations with the fixed TEP1*R1 resistant allele have been documented in A. coluzzii, formerly known as the A. gambiae M-form, from Mali and Burkina Faso, their resistance to P. falciparum infections has not been experimentally evaluated28,29. In areas where R mosquitoes are prevalent, parasites that developed ways to evade TEP1-mediated killing would have a considerable transmission advantage whilst the selective pressure would be less pronounced in areas with lower prevalence of R mosquitoes. Susceptibility of NF165 to TEP1 mediated killing reported here could thus result from a lower exposure to R mosquito populations. NF165 was isolated in Malawi in East Africa, where TEP1*R1 allele is rare, supporting this hypothesis. In contrast, NF166 originates from Guinea, that borders Mali where TEP1*R1 mosquito populations are more abundant. Similarly, no TEP1*R1 alleles have been described in Cameroon and parasite resistance to mosquito immune pressure may have developed through other, TEP1-independent, mechanisms. This is in line with the previous observations on TEP1 susceptibility of the Brazilian P. falciparum 7G8 which is transmitted by the Anopheline vectors that lack TEP1 driven parasite killing25. We therefore propose that evolution of parasite resistance to TEP1 killing may result in adaptations within mosquito populations that result in variation at global (South America as opposed to Africa) and more local scale. Our findings indicate that resistance to P. falciparum in R mosquitoes is only partially determined by TEP1 as removal of this protein does not fully restore oocyst densities to levels seen in S mosquitoes.

We observed a considerable negative effect of wounding on oocyst development for all P. falciparum strains in the S mosquitoes and for two out of three P. falciparum strains in the R mosquitoes. Previous studies in S mosquitoes have shown that experimentally-induced wounding promotes P. falciparum killing via REL1/REL2 and AP-1/Fos pathways that control expression of TEP1 and a gene encoding transglutaminase 2, respectively18,27. As injection caused a significant reduction in the survival of TEP1-resistant NF54 parasites, we conclude that the observed wounding phenotype does not require TEP1 function. In fact, the wounding effect was less pronounced in R compared to S mosquitoes. The wounding thereby does not affect our conclusions based on the results obtained with TEP1 depletion by micro-injection.

While questions remain about the exact mechanism of TEP1-mediated killing in A. gambiae, our data demonstrate that TEP1 is an important determinant of the success of P. falciparum transmission. Our findings suggest that African P. falciparum populations vary in their susceptibility to TEP1-mediated killing and that this variation is more complex and goes beyond the Pfs47 locus.

Materials & Methods

Mosquito rearing, parasite infections and mosquito midgut dissections

A. gambiae Ngousso (S) and A. gambiae L3–5 (R) mosquitoes were reared at 27–30 oC and 70–80% humidity in a 12/12 hour day/night cycle. For infection experiments, mosquitoes were fed on a glass membrane feeder system containing ~1,25 mL of P. falciparum culture mixture as described before30. Three P. falciparum strains, NF54 (African origin)31, NF165 (Malawi) and NF166 (Guinea), were cultured as described before32. Female BALB⁄cByJ and C57BL ⁄6J, 8 weeks of age, were purchased from Elevage Janvier (Le Genest Saint Isle, France). Rodent experiments were performed according to the regulations of the Dutch “Animal On Experimentation act” and the European guidelines 86 ⁄ 609 ⁄EEG. Approval was obtained from the Radboud University Experimental Animal Ethical Committee (RUDEC 2009-019, RUDEC 2009-225). P. berghei (ANKA) was passaged in C57BL/6J mice and parasitemia was assessed using Giemsa-stained slides of tail blood. Animals were anesthetized using the isoflurane-anaesthesia system and mosquitoes were fed for 10 min.

Unfed mosquitoes were removed from the samples. Blood-fed mosquitoes were maintained at 26 °C or 21 °C, for P. falciparum and P. berghei infections, respectively and 70–80% humidity. Midguts were dissected 6–9 days post infection in 1% merchurochrome staining solution. Numbers of oocyst were counted using an Axio Scope A1 microscope (Zeiss).

Polymorphism detection by PCR

Genomic DNA was isolated from mosquitoes and used as a template for PCR genotyping. Specific primers: TEP1 fwd 5′-AAAGCTACGAATTTGTTGCGTCA-3′ as a universal primer, TEP1-S rev 5′-ATAGTTCATTCCGTTTTGGATTACCA-3′ for susceptible strain and TEP1-R rev 5′-CCTCTGCGTGCTTTGCTT-3′ for resistant strain, amplified fragments of 372 bp and 349 bp, respectively. Standard program was used; 4 min at 94 °C, then 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 54 °C, 60 s at 72 °C for 35 cycles and finally 7 min at 72 °C.

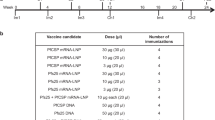

dsRNA synthesis, injection and immunoblotting

Double-stranded RNAs were synthesized from plasmids pLL17 (dsTEP1) and pLL100 (dsLacZ) using the T7 Megascript Kit (Ambion) as described previously10,21. One-day-old female mosquitoes were anesthetized on a CO2 pad, injected with 69 nL of dsRNA (3 μg/μL) using a Nanoject II injector system (Drummond; Broomall, PA) and 4–8 days later fed with the P. falciparum cultures or on infected P. berghei mice. Unfed mosquitoes were removed from cages and the efficiency of gene silencing was monitored by immunoblotting. Hemolymph of 7–8 dsRNA treated mosquitoes was collected by proboscis clipping into denaturizing protein loading buffer (1:2 SDS, 1:10 DTT in PBS) and samples were separated by 7% SDS-PAGE. After protein membrane transfer, the specificity of TEP1 knockdown was examined using TEP1-specific antibodies (1:500) revealing 165 kDa full-length and 80 kDa cleaved forms of the protein. Antibodies against prophenoloxidase 2 (PPO2) (1:10,000) were used as a loading control. Bound antibodies were detected by anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to HRP at 1:10,000 and addition of chromogen and peroxide.

Pfs47 DNA sequence analysis

Genomic DNA of P. falciparum strains NF54, NF165 and NF166 was isolated from asexual parasite culture material using QIAmp DNA Blood mini kit (Qiagen, NL). Procedures for recovery of DNA from P. falciparum African isolates were described in Nsango et al. 2012. Briefly, gametocytes were purified by magnetic separation of 1 mL of serum-free blood on a LD separation column using the MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) and DNA was extracted with DNAzol according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Research Center, USA).

Specific primers were used; BVS300 fwd: ‘5-TACATTCAAATAACTCAGAGGGTAAC-3′ and BVS301 rev: ‘5-GTTTGTGTATATTTACCTTACATTTATCTCC-3′ to amplify the Pfs47 gene fragment of 3,319 bp. HotStar HiFidelity Polymerase (Qiagen, NL) and long PCR amplification program was used; 5 min at 94 °C and then 30 s at 94 °C, 60 s at 48 °C, 10 min at 62 °C for 30 cycles and finally 15 min at 68 °C. Amplification products were then analysed on 1% agarose gel and purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, NL) or AMPure PCR DNA purification kit (Agencourt, MA). Sequence analysis was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate between nucleotides 0–417 using primer BVS202 rev 5′-CCGTTTTACTATTATCACATCTAC-3′ and between nucleotides 500–860 using primer MWV325 fwd 5′-GTAGATGTGATAATAGTAAAACGG-3′ (based on data of other P. falciparum strains the Pfs47 locus between nucleotide 417–500 was shown to have no polymorphisms). Results were compared to available P. falciparum Pfs47 sequences (i.e. NF54, 7G8) using Jalview, SegScape and Vector NTI (Invitrogen, UK).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in STATA version 12 (Statacorp, College Station, Texas, US). The effect of TEP1 knockdown was determined by comparing oocyst burden after dsTEP injection and dsLacZ injection. For this, a negative binomial regression model was fitted to the oocyst count data per parasite isolate and per mosquito strain using random-effects and conditional fixed effects overdispersion models (xtnbreg command in Stata), combining data from all experiments and adjusting for correlations between observations from the same experiment. A potential effect of injection on oocyst development was tested by comparing oocyst burden after dsLacZ with that in noninjected mosquitoes, using the same approach.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Eldering, M. et al. Variation in susceptibility of African Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites to TEP1 mediated killing in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Sci. Rep. 6, 20440; doi: 10.1038/srep20440 (2016).

Change history

24 March 2016

The version of this Article previously published omitted Teun Bousema and Elena A. Levashina as corresponding authors. Correspondence and request for materials should also be addressed to teun.bousema@radboudumc.nl and Levashina@mpiib-berlin.mpg.de. This has now been corrected in the PDF and HTML versions of the Article.

References

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report (2014) Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2014/report/en/(Accessed: 24th July 2015).

Vaughan, J. A. Population dynamics of Plasmodium sporogony. Trends in Parasitology 23, 63–70 (2007).

Niare, O. et al. Genetic loci affecting resistance to human malaria parasites in a West African mosquito vector population. Science 298, 213–216 (2002).

Riehle, M. M. et al. A cryptic subgroup of Anopheles gambiae is highly susceptible to human malaria parasites. Science 331, 596–8 (2011).

Collins, F. H. et al. Genetic selection of a Plasmodium-refractory strain of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Science 234, 607–10 (1986).

Vernick, K. D. et al. Plasmodium gallinaceum: A Refractory Mechanism of Ookinete Killing in the Mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Experimental Parasitology 80, 583–595 (1995).

Dong, Y. et al. Anopheles gambiae immune responses to human and rodent Plasmodium parasite species. PLoS.Pathog. 2, e52 (2006).

Garver, L. S., Xi, Z. & Dimopoulos, G. Immunoglobulin superfamily members play an important role in the mosquito immune system. Dev.Comp Immunol. 32, 519–531 (2008).

Abraham, E. G. et al. An immune-responsive serpin, SRPN6, mediates mosquito defense against malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 16327–32 (2005).

Levashina, E. A. et al. Conserved role of a complement-like protein in phagocytosis revealed by dsRNA knockout in cultured cells of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Cell 104, 709–718 (2001).

Barillas-Mury, C. et al. Immune factor Gambif1, a new rel family member from the human malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. EMBO J 15, 4691–701 (1996).

Frolet, C., Thoma, M., Blandin, S., Hoffmann, J. A. & Levashina, E. A. Boosting NF-kappaB-dependent basal immunity of Anopheles gambiae aborts development of Plasmodium berghei. Immunity 25, 677–85 (2006).

Christophides, G. K. et al. Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science 298, 159–165 (2002).

Meister, S. et al. Immune signaling pathways regulating bacterial and malaria parasite infection of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11420–11425 (2005).

Fraiture, M. et al. Two mosquito LRR proteins function as complement control factors in the TEP1-mediated killing of Plasmodium. Cell Host.Microbe 5, 273–284 (2009).

Garver, L. S., Dong, Y. & Dimopoulos, G. Caspar controls resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in diverse anopheline species. PLoS.Pathog. 5, e1000335 (2009).

Gupta, L. et al. The STAT pathway mediates late-phase immunity against Plasmodium in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Cell Host Microbe 5, 498–507 (2009).

Nsango, S. E. et al. AP-1/Fos-TGase2 Axis Mediates Wounding-induced Plasmodium falciparum Killing in Anopheles gambiae. J Biol Chem 288, 16145–54 (2013).

Garver, L. S., de Almeida Oliveira, G. & Barillas-Mury, C. The JNK pathway is a key mediator of Anopheles gambiae antiplasmodial immunity. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003622 (2013).

Povelones, M., Waterhouse, R. M., Kafatos, F. C. & Christophides, G. K. Leucine-rich repeat protein complex activates mosquito complement in defense against Plasmodium parasites. Science 324, 258–261 (2009).

Blandin, S. et al. Complement-like protein TEP1 is a determinant of vectorial capacity in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Cell 116, 661–670 (2004).

Blandin, S. A. et al. Dissecting the genetic basis of resistance to malaria parasites in Anopheles gambiae. Science 326, 147–150 (2009).

Zheng, L. et al. Quantitative trait loci for refractoriness of Anopheles gambiae to Plasmodium cynomolgi B. Science 276, 425–8 (1997).

Blandin, S. & Levashina, E. A. Thioester-containing proteins and insect immunity. Mol.Immunol. 40, 903–908 (2004).

Molina-Cruz, A. et al. Some strains of Plasmodium falciparum, a human malaria parasite, evade the complement-like system of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1957–E1962 (2012).

Molina-Cruz, A. et al. The human malaria parasite Pfs47 gene mediates evasion of the mosquito immune system. Science 340, 984–7 (2013).

Nsango, S. E. et al. Genetic clonality of Plasmodium falciparum affects the outcome of infection in Anopheles gambiae. International Journal for Parasitology 42, 589–595 (2012).

Obbard, D. J. et al. The evolution of TEP1, an exceptionally polymorphic immunity gene in Anopheles gambiae. BMC Evol Biol 8, 274 (2008).

White, B. J. et al. Adaptive divergence between incipient species of Anopheles gambiae increases resistance to Plasmodium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 244–9 (2011).

Ponnudurai, T. et al. Infectivity of cultured Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes to mosquitoes. Parasitology 98 Pt 2, 165–173 (1989).

Conway, D. J. et al. Origin of Plasmodium falciparum malaria is traced by mitochondrial DNA. Mol Biochem Parasitol 111, 163–71 (2000).

Ponnudurai, T., Lensen, A. H., Leeuwenberg, A. D. & Meuwissen, J. H. Cultivation of fertile Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in semi-automated systems. 1. Static cultures. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 76, 812–8 (1982).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Jolanda Klaassen, Astrid Pouwelsen, Laura Pelser-Posthumus and Jacqueline Kuhnen for their work on mosquito breeding and handling of the infected mosquitoes. The authors also would like to thank Bas E. Dutilh and Nathalie de Wagenaar from the CMBI for providing Pfs47 sequence data. This work was supported by funds from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreements N°242095 (EVIMalar) and N°223601 (MALVECBLOK). T. Bousema is further supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO Vidi 016.158.306).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E., E.A.L. and R.S. designed experiments. M.E., G.J.v.G., M.V.-B., W.G., R.S.-S., W.R., M.V. and L.A. performed experiments. M.E., T.B., L.A., I.M., E.A.L. and R.S. analysed the data. M.E. and M.V. performed sequence comparisons. M.E., T.B., E.A.L. and R.S. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Eldering, M., Morlais, I., van Gemert, GJ. et al. Variation in susceptibility of African Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites to TEP1 mediated killing in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Sci Rep 6, 20440 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20440

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20440

This article is cited by

-

Distribution of Anopheles gambiae thioester-containing protein 1 alleles along malaria transmission gradients in The Gambia

Malaria Journal (2023)

-

Molecular characterization and genotype distribution of thioester-containing protein 1 gene in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes in western Kenya

Malaria Journal (2022)

-

A portfolio of geographically distinct laboratory-adapted Plasmodium falciparum clones with consistent infection rates in Anopheles mosquitoes

Malaria Journal (2021)

-

Sexual forms obtained in a continuous in vitro cultured Colombian strain of Plasmodium falciparum (FCB2)

Malaria Journal (2020)

-

Chimeric symbionts expressing a Wolbachia protein stimulate mosquito immunity and inhibit filarial parasite development

Communications Biology (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.