Abstract

Two-dimensional MoS2 is a promising material for future nanoelectronics and optoelectronics. It has remained a great challenge to grow large-size crystalline and high surface coverage monolayer MoS2. In this work, we investigate the controllable growth of monolayer MoS2 evolving from triangular flakes to continuous thin films by optimizing the concentration of gaseous MoS2, which has been shown a both thermodynamic and kinetic growth factor. A single-crystal monolayer MoS2 larger than 300 μm was successfully grown by suppressing the nuclei density and supplying sufficient source. Furthermore, we present a facile process of transferring the centimeter scale MoS2 assisted with a copper thin film. Our results show the absence of observable residues or wrinkles after we transfer MoS2 from the growth substrates onto flat substrates using this technique, which can be further extended to transfer other two-dimensional layered materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) layered materials have attracted much attention due to their unique properties1,2,3,4. The existence of a semiconductor bandgap in transitional metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), including MoS2, WS2, MoSe2 and WSe2, makes them promising for future logic devices and circuits beyond graphene. Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) has been demonstrated as a deterministic method in producing large-area and high-quality monolayer 2D layered TMD materials5,6,7,8,9,10,11. According to the method of placing the source materials in the furnace, the CVD growth can be divided into vapor sulfurization and vapor deposition. In the vapor sulfurization, the source materials, e.g., Mo5, MoO36,7 or (NH4)2MoS4 8, are coated on a substrate, which is followed by sulfurization in a sulfur vapor environment at high temperature. The TMDs grown by sulfurization method usually have large area and good uniformity but poor crystalline quality, small domain size and uncontrollable layer number. In contrast, the source materials, e.g., MoO39,10 or MoCl511, are evaporated in the vapor deposition method. The TMDs grown by this method usually have relative large domain size but poor surface coverage on a substrate. These two kinds of CVD methods both require high growth temperature (up to ~800 °C), which cannot meet the requirements of the back-end processing of integrated circuit technology and restricts the substrate selection, e.g., the plastic substrate for flexible electronics applications.

To fulfill the potential of the 2D layered TMD materials, it is important to grow large domain-size and high surface-coverage TMDs and transfer TMDs from the growth substrate to another without compromising the quality of the TMDs. The conventional PMMA-mediated transfer technique suffers from the failure of completely removing polymeric residues and the formation of the wrinkles in the TMD thin films. These drawbacks significantly degrade the performance of the TMD-based devices. Recently, Gurarslan et al. and Li et al. reported that monolayer MoS2 can be peeled off from the growth substrates by using polystyrene and poly(L-lactic acid) based on different surface properties between the polymers and the growth substrates12,13. These methods, compared to conventional PMMA transfer, prevents the crack of the monolayer MoS2 thin films during substrate etching process, but fails to avoid the use of polymer carriers, which generates polymeric residues and mechanical wrinkles. A dry transfer process for transferring graphene by mechanical delamination has been developed on the basis of different adhesion energy between the graphene on Cu foil and the target substrates14,15. However, it is easy to generate cracks on graphene during the transfer because of the adhesion between graphene and Cu foil. In addition, the use of epoxy between graphene and target substrate contaminates the surface of graphene. It is highly desirable to develop a resist-free and wrinkle-free transfer method.

In this work, we first controllably grow monolayer MoS2 from triangular islands to continuous thin film using vapor deposition method. After optimizing the growth parameters, we demonstrate the growth of monolayer MoS2 flake with large domain size (up to ~300 μm) and high surface coverage which are of great potential for variously applications. To avoid the polymeric residue and wrinkles generated in the PMMA-mediated transfer method, we present a facile transfer process using thermal release tape (TRT) assisted with a Cu thin film, preventing the MoS2 from direct contact to the glue and giving rise to the resist-free MoS2 surface. The tape and Cu thin film also provide mechanically robust supports for the monolayer MoS2 thin film, reducing the wrinkles generated during the transfer process. Our method allows us to transfer MoS2 from the growth substrate onto flat substrates without observable polymeric residues or wrinkles.

Results and Discussion

We developed a CVD setup at atmospheric pressure similar to that reported in ref 16 (Fig. 1a). The temperatures of the locations for placing MoO3 and S precursors were controlled by the furnace and the heating belt, respectively. The sulfur gas was carried into the growth zone by Ar gas flow. Excessive amount of S were used to ensure MoO3 precursor react completely. In the previous works17,18, the MoO3 powder and the growth substrate were placed in the middle and downstream of the furnace, respectively. In our work, the growth substrate was placed on top of the quartz boat, facing downwardly towards the MoO3 precursor substrate, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 1b. To quantitatively control the amount of MoO3, we replaced commonly-used MoO3 powder10,17,18 with a MoO3-coated substrate as the precursor. The amount of the precursor can be adjusted by the size of the MoO3-coated substrates to successfully grow monolayer MoS2. Figure S1a shows the photograph of one typical growth substrate. Centimeter scale area of the substrate is covered with the MoS2 product. The optical images of the MoS2 at a series of points marked in Figure S1a show similar morphologies at these points, implying that the as-grown MoS2 is large area.

The MoS2 grown by vapor deposition methods are usually triangular flakes with low surface coverage, in agreement with those reported in existing literatures17,19. For the fabrication of electronic device, it is highly desirable to grow continuous and large domain size MoS2 thin films. The domains in the continuous MoS2 thin films are referred to the shape surrounded by the boundaries, in which the adjacent domains overlap at the boundary and provide abruptly optical contrast. The growth of the continuous MoS2 thin film is presumed to include five major steps:11,18,20 (1) the sublimation of the precursor (MoO3 and S) and the mass transport of the precursor to the region close to growth substrate, (2) the reaction of MoO3 and S to form gaseous MoS2, (3) the precipitation of supersaturated MoS2 vapor onto the substrate to produce solid-phase MoS2 nuclei, (4) the MoS2 growth on the substrate controlled by kinetic factors and (5) the coalescence of the adjacent MoS2 domains to merge into continuous thin films.

In general, the nuclei density is closely related to the average domain size of MoS2. The increase of the nuclei density can improve the surface coverage but decrease the average domain size. In contrast, the suppression of nuclei density helps to grow large-size crystalline domain21, though the product from low-density nuclei usually has poor surface coverage. Therefore, it is quite important to optimize the nuclei density to fabricate continuous MoS2 thin films with large domain size as well as high surface coverage. The concentration of the gaseous MoS2 (Cg) has been shown with an important thermodynamics and kinetics factor for the precipitation reaction (Cg → Cs), where Cs is the concentration of the active species at the substrate surface11. In our CVD setup, the excessive S precursor outside the furnace is carried by Ar gas. The S concentration almost keeps constant in the middle of the furnace tube and has a negligible influence on the nuclei density. On the other hand, the MoO3 precursor is thermally evaporated from the bottom of the quartz boat, reacts with S to form gaseous MoS2 and diffuses across the boundary layer towards the growth substrate. The distance between the MoO3 precursor substrate and the MoS2 growth position is defined as d. The relationship between the concentration of the gaseous MoS2 (Cg) and the distance d can be described according to equation (1):22

where Cg(d, t) and Cg(0, t) are the concentration of gaseous MoS2 at the given distance d and the source substrate, t is the time and D is the diffusion constant. The concentration of the gaseous MoS2 changes dramatically as a function of d, as schematically plotted in Fig. 1c. This allows us to investigate the effect of the concentration of gaseous MoS2 on the controllable growth.

Figure 2a–e show the optical images of the typical as-grown MoS2 with different source/substrate distances d. When the distance is kept relatively short (~5 mm), the concentration of the gaseous MoS2 Cg is high. Figure 2a shows that the substrate surface is fully covered by MoS2 thin film and the average domain size is approximately 20 μm. The domain boundaries of the thin film can be easily observed by optical microscopy because the adjacent domains overlap at the boundary and provide optical contrast. With the short distance d, the high Cg ensures that the precipitation reaction can happen and numerous sites on the surface of growth substrate can satisfy the thermodynamic conditions, resulting in high nuclei density (5.7 × 103/mm2). When the distance increases to 6.5 mm, the MoS2 thin film still fully covers the growth substrate, as shown in Fig. 2b. The nuclei density rapidly decreases with lower Cg, which allocates relatively large space for each nucleus to grow before the coalescence. As a result, the average domain size is increased to around 40 μm. Figure 2c displays the optical image of the edge of MoS2 thin film, where the distance d is around 7 mm. The overall surface coverage decreases to around 85%. In the middle part of the growth substrate, the average domain size increases to 75 μm. Triangular flakes are distributed at the edge of MoS2 thin films. Some overlapping flakes illustrate the initial process of the formation of the thin film. As the nuclei density is relatively low in the edge part, enough space is spare for the MoS2 domain to grow independently. It is worthy highlighting that the large-size crystalline MoS2 flake (>300 μm) has been successfully grown at this distance, Fig. 2f shows a crystalline MoS2 flake with the size of 308 μm. With the continuous decrease of the Cg at the longer distance (7.5 mm), the dominant products are triangular MoS2 (Fig. 2d) because the nuclei density is suppressed by the low concentration of the gaseous MoS2. The surface coverage is decreased to 70% and the average domain size drops to 60 μm. Low-density nuclei guarantee that most flakes can be grown independently without the overlap between the adjacent flakes until the end of the growth. When the d is further increased to 9 mm, the shape of the products are triangular flakes with the mean size of ~25 μm and the surface coverage is only ~30%, as shown in Fig. 2e. The low Cg fails to supply sufficient source, resulting in the decrease of both surface coverage and average domain size.

The surface coverage and the average domain size as a function of the source/growth distance are summarized in Fig. 3a. The nuclei density is calculated from 0.47 mm × 0.33 mm area and plotted in Fig. 3b. It exhibits two distinct trends in the both two plots with the distance of 7 mm as the boundary point. In the region where the growth substrate is close to the precursor substrate (less than 7 mm), the continuous MoS2 thin films are dominant products. The shape of the MoS2 domain exhibits irregular, deviating from triangle or rhomboidal. The surface coverage remains 100% and slightly decreases near the edge of MoS2 thin films. Meanwhile, the average domain size increases from ~23 μm to 75 μm. This is because that the high Cg gives rise to both high-density nuclei and sufficient source supply. Sufficient gaseous MoS2 supply guarantees that the high-density nuclei can keep growing until the domains merge into continuous thin films. With the distance of 7 mm, the large domain size and high surface coverage MoS2 thin films are grown. The average domain size of the crystalline MoS2 is around 75 μm in the middle part and larger than 300 μm in the edge part. The low-density nuclei help to grow large domain size without comprising the surface coverage, ascribed to the coincident match between the nuclei density and the source supply. Large-size MoS2 flakes over 200 μm were reproducibly grown under this condition, as shown in Fig. 3c–f.

In the range of relatively long distance (more than 7 mm), the surface coverage and average domain size both decrease with the increase of the distance. The low Cg results in low-density nuclei and insufficient source supply for the surface precipitation. Without sufficient gaseous MoS2 supply, the nuclei can grow independently during the growth procedure but fail to fully cover the surface. The insufficient MoS2 supply leads to smaller size of domain. Interestingly, the nuclei density is expected to decline with the increase of the distance. But a slight increase is presented in Fig. 3b. After the abrupt decrease of nuclei density, the increased spare space for each nuclei growth prevent some nuclei from being absorbed by adjacent domains and allow them to grow to observable size, which gives rise to the increase of the nuclei density.

We measured the thickness of MoS2 thin films (Fig. 4a) and flakes (Fig. 4b) with Raman spectroscopy and atomic force microscope (AFM). Figure 4c shows the corresponding Raman spectra of the thin film and the flake. The peak difference between the in-plane mode E12g and out-of-plane mode A1g peaks is 20 cm−1 at the points of P1 and P2, which represent MoS2 films and flakes, respectively. This indicates that the films and flakes are both monolayer23. The AFM images in Figure S2a and 2b show that the thickness of the MoS2 flake and film are ~0.8 nm and ~0.9 nm, further confirming the monolayer characteristics4,9. We also investigated the domain boundaries of the MoS2 thin film (P3 in Fig. 4a). The boundaries provide extra nucleation point for the MoS2 growth. Compared to the Raman spectra of the center of the MoS2 thin film, the E12g peak of P3 shows a red shift while the A1g peak of P3 presents a blue shift. The E12g-A1g peak difference increases to 23 cm−1. The photoluminescence in domain boundaries region, as shown in Figure S3, also presents a much lower signal than that in the monolayer region. Figure 4d shows the AFM image of the boundary of two domains. A second layer of MoS2 has been grown in the boundary region and part of the MoS2 is 3~4 layers, which is illustrated in the corresponding height profile in Fig. 4e.

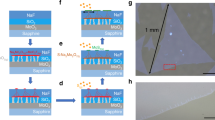

The MoS2 can be only grown on a few kinds of substrates (SiO2 or sapphire) at high temperature. To extend the applications of MoS2 device, it requires researchers to develop a low-temperature process to transfer MoS2 on various substrates, e.g., ultra-high-k substrate or plastic substrate24,25. Figure 5 illustrates the schematics of the transfer process using thermal release tape (TRT)26,27. To prevent the direct contact between the MoS2 surface and the glue, MoS2 was first coated with a Cu thin film (~60 nm thickness) which can provide robust mechanical support and relative strong adhesion with MoS2 (Fig. 5b). The TRT has a strong adhesion with the Cu thin film at room temperature, which helps to completely peel MoS2 off from the growth substrate. The photograph in Fig. 5d clearly shows that this transfer method is applicable to centimeter-scale sample transfer. After the tape was pressed onto a target substrate, the substrate with the MoS2/Cu/TRT was heated from room temperature to 120 °C. The tape lost the adhesion and automatically peeled off (Fig. 5e), leaving the MoS2 and Cu thin film onto the target substrate (Fig. 5f). The MoS2 on the growth substrate (Fig. 5a, 2 cm × 2 cm) was transferred onto a 3 cm × 3 cm SiO2/Si substrate without notable changes (Fig. 5g). Figure S4 presents the large-area transferred film in Fig. 5g. We also transferred as-grown MoS2 onto SiO2/Si substrates by conventional PMMA mediated method as control samples6.

Illustration of the transfer process assisted with a Cu thin film. Photographs of the transfer processes.

(a) as-grown MoS2 on SiO2/Si substrate; (b) coating the MoS2 with a Cu thin film; (c) sticking TRT; (d) peeling off TRT together with MoS2; (e) heating the target substrate to peel off TRT; (f) the MoS2 and Cu thin film on the target substrate; (g) the transferred MoS2 after Cu etching.

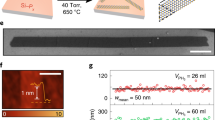

Figure 6a,b show the MoS2 flakes before and after PMMA transfer. Compared to the as-grown MoS2, the PMMA-transferred MoS2 presents remarkable resist residues although the sample has been cleaned with acetone for long time. It has been reported that some polymeric residues are still observed on the surface of the transferred graphene when the PMMA-mediated transfer method is applied28,29,30,31,32. The free radicals form during PMMA cleaning process and result in the difficulty of completing removing PMMA residuals28. Long and heavy molecular fragments can attach to these radical sites and interact with the adjacent polymer chain. Several techniques such as chloroform treatments29, plasma exposure30 and annealing under gaseous (H2 and Ar) or high vacuum conditions31,32 are used to remove polymer contaminants. Though these techniques achieved some degrees of success, they are far from satisfactory for obtaining clean surface because the process flows are complicated and suffer from process specific drawbacks33. The harsh environment required in these techniques has uncertain influence on monolayer MoS213, which is subject to further investigation. These polymeric residuals will degrade the performance of the electronic and optical devices based on MoS2. In contrast, Fig. 6c,d present the typical optical images of the as-grown and TRT transferred MoS2 flakes, respectively. There is no significant difference between the as-grown and the TRT transferred samples. The surfaces of the samples are clean, indicating the absence of observable resist residues. The Cu thin film introduced between MoS2 and TRT prevents the MoS2 from directly exposing to the glue. Compared to polymer, Cu thin film is relatively easier to be completely etched, which has been widely adopted for transferring graphene34. The EDX spectrum and XPS spectra in Figure S5 clearly show that no Cu residual exists after the etching process.

Optical images of the MoS2 (a) before and (b) after the PMMA-mediated transfer process. Optical images of the MoS2 (c) before and (d) after the TRT transfer process. SEM images of the MoS2 transferred by (e) PMMA method and (f) TRT method. (g) Illustration of wrinkle generation during PMMA transfer process and the inserted image is photograph of the PMMA/MoS2 film floating on the KOH solution during TRT transfer process.

The SEM image in Fig. 6e presents the evidence of the generated wrinkles on MoS2 thin films after the PMMA-mediated transfer process. Figure 6f shows the SEM image of the TRT-transferred continuous MoS2 thin film. The flat and uniform characteristics of the transferred thin film suggest that no wrinkles were generated during our transfer process. The Young’s modulus of the Cu thin film (~100 GPa) is comparable with that of MoS2 (~270 GPa)35,36. It provides mechanically robust support for MoS2 thin films and reduces wrinkle generation during the transfer process. It also diminishes the strain induced when the TRT was peeled off during the temperature ramp process. On the contrary, PMMA has a low Young’s modulus about 22 MPa37, far below that of monolayer MoS2. Although this enables PMMA to release the growth strain, PMMA cannot provide sufficiently robust support for the MoS2 during the transfer process38. The wrinkle generation is illustrated in Fig. 6g. During the PMMA transfer process, the underlying SiO2 layer is etched by KOH or NaOH solution12. Bubbles are generated in the etching process and can be trapped by the PMMA thin film, which will induce capillary force and give rise to wrinkles or even cracks (inset image in Fig. 6g). Additionally, it is difficult to avoid the PMMA folding when we fish it out of the etching solution with target substrates. However, in our transfer technique, the Cu thin film and the TRT with robust mechanical support ensures the flatness and integrality of MoS2 thin film during the transfer, presented by the photography in Fig. 5d. The AFM images in Figure S6 further confirm that our TRT-transferred technique allows us to transfer large-area monolayer MoS2 residual-free and wrinkle-free.

Figure 7a shows the Raman spectra of the as-grown and transferred MoS2. The peak frequency difference between the in-plane mode E12g and the out-of-plane mode A1g peaks remains around 19~20 cm−1 after the transfer by PMMA and TRT methods, indicating that the layer number remains monolayer23. The peak position of the in-plane mode E12g in Raman spectra is sensitive to the strain and can be used as an indicator of the strain39. The peak position remains unchanged before and after the TRT transfer. However this peak redly shift about 2 cm−1 after the transfer by PMMA, which results from the local strain induced by the wrinkle generated during the transfer40. This is also in agreement with our morphology characterization. The peak position of the out-of-plane mode A1g is less affected by the strain than the in-plane E12g mode39. The slight down-shift of the A1g mode of the MoS2 by PMMA-mediated transfer method also indicates the presence of the strain after the transfer40. However, the A1g mode upshifts after the TRT transfer shows a different trend. The stiffening A1g mode is associated with the p-doping in the MoS241, coming from the charged impurities, which is unavoidably introduced at the interface between the MoS2 and the target substrates during the transfer process42. This impurities also exist in PMMA-mediated transferred MoS2, but the doping yields to the effect of the strain and fails to stiffen A1g mode40.

Figure 7b shows the photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the MoS2 samples. After PMMA-mediated transfer, two striking PL changes are observed: first, the emission is shifted by 10 nm to lower energy; second, the intensity is rapidly decreased. As PMMA cannot provide mechanical robust support for the MoS2, it is unavoidable to introduce local strain into MoS2 samples during the PMMA-mediated transfer process. It has been reported that the uniaxial strain on monolayer MoS2 gives rise to the red shift of PL peak and the reduced peak intensity due to the change of band structure and the reduction in the band gap energy40,43,44, which is also observed in our work. And the change of band structure is attributed to the weak PL signal of PMMA-transferred MoS243. In contrast, the PL peak positions of the TRT-transferred MoS2 are comparable to that of the as-grown MoS2 in terms of peak position. However, the peak intensity shows a slightly decrease and the full width at half maximum (FWHM) increases, which is induced by charge doping as we observe from the Raman results. The direct-gap transition peak (A peak) can be fitted with two peaks: A exciton peak and A− trion peak45, shown in the inserted figure in Fig. 7b. The A− trion peak is sensitive to the electron density and the intensity will decrease by p-doping46. The A− trion intensity of TRT-transferred MoS2 decreases due to the impurities at the interface, making the principal peak slightly lower than that of as-grown MoS2.

Conclusions

We fabricated MoS2 triangular flakes and continuous thin films by changing the distance between source and growth substrates. The effects of the nuclei density on the domain size and surface coverage were systematically investigated. By optimizing the growth conditions, we have successfully grown single-crystalline MoS2 flake with the size larger than 300 μm. We also developed a transfer process assisted with a Cu thin film, which allows us to transfer MoS2 onto flat substrates. The optical and SEM images confirmed the absence of observable residues and wrinkles on the transferred MoS2. The properties were measured by Raman and PL suggesting the transferred MoS2 maintained qualities as the as-grown one. Although this work focused on the transfer of MoS2, this process can be extended to the transfer of other 2D layered materials.

Methods

MoO3-coated substrate preparation

MoO3 was prepared by conventional hydrothermal synthesis47 and fully dissolved in ethanol. The mixture was then dropped onto a Si substrate with 300-nm-thick SiO2 and the substrate was heated to approximately 110 °C on a hot plate to evaporate ethanol. The procedure was repeated until the remaining MoO3 completely covered the substrate.

CVD method

MoS2 was grown on a Si substrate with 300-nm-thick SiO2 by CVD method. The growth substrate faced downwardly above a quartz boat. Below the growth substrate, a 5 mm × 5 mm MoO3-coated substrate (about 10-30 mg MoO3) was placed as the Mo precursor. The quartz boat was then loaded into a 1-inch-diameter quartz tube and centered in the furnace. A porcelain boat with sulfur was located in the upstream region outside the furnace, approximately 25 cm away from the middle. Before the MoS2 growth, the system was flushed with 200 sccm of Ar gas for 10 min. Afterwards, the MoO3 was heated from room temperature to ~800 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min and then maintained at 800 °C for 10 min. Meanwhile, the sulfur was sublimated at 160 °C and carried by Ar gas flow to the growth zone. The Ar gas flow was initially 150 sccm and when the growth region reaches 700 °C, it was reduced to 60 sccm to prevent excessive sulfur from suppressing the evaporation of the Mo source. The growth ended with natural cooling of the system.

Transfer by thermal release tape

The substrate with as-grown MoS2 sample was first coated with a ~60-nm-thick Cu thin film by thermal evaporation. A thermal release tape was then pressed onto the SiO2/Si substrate and was gently peeled off. As a result, the Cu/MoS2 stack was separated from the SiO2/Si substrate and attached to the tape. Second, the tape carrying Cu/MoS2 was pressed onto a targeted substrate. The whole stack was heated to approximately 120 °C. The adhesiveness between thermal release tape and Cu was weakened. Therefore the tape can be easily peeled off, leaving the Cu/MoS2 on the target substrate. Finally, the Cu thin film was etched using the mix of 15% ammonium persulphate and deionization water, followed by a modified RCA clean process34.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lin, Z. et al. Controllable Growth of Large–Size Crystalline MoS2 and Resist-Free Transfer Assisted with a Cu Thin Film. Sci. Rep. 5, 18596; doi: 10.1038/srep18596 (2015).

References

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat Chem 5, 263–275 (2013).

Xu, M., Liang, T., Shi, M. & Chen, H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem. Rev. 113, 3766–3798 (2013).

Ganatra, R. & Zhang, Q. Few-Layer MoS2: A Promising Layered Semiconductor. ACS nano 8, 4074–4099 (2014).

Zhan, Y., Liu, Z., Najmaei, S., Ajayan, P. M. & Lou, J. Large-area vapor-phase growth and characterization of MoS(2) atomic layers on a SiO(2) substrate. Small 8, 966–971 (2012).

Lin, Y. C. et al. Wafer-scale MoS2 thin layers prepared by MoO3 sulfurization. Nanoscale 4, 6637–6641 (2012).

Wang, X., Feng, H., Wu, Y. & Jiao, L. Controlled synthesis of highly crystalline MoS2 flakes by chemical vapor deposition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5304–5307 (2013).

Liu, K. K. et al. Growth of large-area and highly crystalline MoS2 thin layers on insulating substrates. Nano Lett. 12, 1538–1544 (2012).

Najmaei, S. et al. Vapour phase growth and grain boundary structure of molybdenum disulphide atomic layers. Nat. Mater. 12, 754–759 (2013).

van der Zande, A. M. et al. Grains and grain boundaries in highly crystalline monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Mater. 12, 554–561 (2013).

Yu, Y. et al. Controlled scalable synthesis of uniform, high-quality monolayer and few-layer MoS2 films. Sci Rep 3, 1866, (2013).

Gurarslan, A. et al. Surface-Energy-Assisted Perfect Transfer of Centimeter-Scale Monolayer and Few-Layer MoS2 Films onto Arbitrary Substrates. ACS nano 8, 11522–11528 (2014).

Li, H. et al. A universal, rapid method for clean transfer of nanostructures onto various substrates. ACS nano 8, 6563–6570 (2014).

Yoon, T. et al. Direct measurement of adhesion energy of monolayer graphene as-grown on copper and its application to renewable transfer process. Nano Lett. 12, 1448–1452 (2012).

Na, S. R. et al. Selective Mechanical Transfer of Graphene from Seed Copper Foil Using Peel Rate Effects. ACS nano 9, 1325–1335 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Shape Evolution of Monolayer MoS2Crystals Grown by Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chem. Mater. 26, 6371–6379 (2014).

Shi, J. et al. Controllable Growth and Transfer of Monolayer MoS2 on Au Foils and Its Potential Application in Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS nano 8, 10196–10204 (2014).

Zhang, J. et al. Scalable growth of high-quality polycrystalline MoS2 monolayers on SiO2 with tunable grain sizes. ACS nano 8, 6024–6030 (2014).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Synthesis of large-area MoS2 atomic layers with chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Mater. 24, 2320–2325 (2012).

Pierson, H. O. Handbook of chemical vapor deposition: principles, technology and applications. (William Andrew, 1999).

Gao, L. et al. Repeated growth and bubbling transfer of graphene with millimetre-size single-crystal grains using platinum. Nat Commun 3, 699, (2012).

Dobkin, D. M. & Zuraw, M. K. Principles of chemical vapor deposition. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2003).

Lee, C. et al. Anomalous lattice vibrations of single-and few-layer MoS2. ACS nano 4, 2695–2700 (2010).

Lee, Y.-H. et al. Synthesis and transfer of single-layer transition metal disulfides on diverse surfaces. Nano Lett. 13, 1852–1857 (2013).

Zhou, C. et al. Low voltage and high ON/OFF ratio field-effect transistors based on CVD MoS2 and ultra high-k PZT gate dielectric. Nanoscale 7, 8695–8700 (2015).

Chai, Y. et al. Low-resistance electrical contact to carbon nanotubes with graphitic interfacial layer. Electron Devices, IEEE Transactions on 59, 12–19 (2012).

Chai, Y. et al. Nanoscale bipolar and complementary resistive switching memory based on amorphous carbon. Electron Devices, IEEE Transactions on 58, 3933–3939 (2011).

Lin, Y.-C. et al. Graphene annealing: how clean can it be ? Nano Lett. 12, 414–419 (2011).

Cheng, Z. et al. Toward intrinsic graphene surfaces: a systematic study on thermal annealing and wet-chemical treatment of SiO2-supported graphene devices. Nano Lett. 11, 767–771 (2011).

Peltekis, N. et al. The effect of downstream plasma treatments on graphene surfaces. Carbon 50, 395–403 (2012).

Kumar, K., Kim, Y.-S. & Yang, E.-H. The influence of thermal annealing to remove polymeric residue on the electronic doping and morphological characteristics of graphene. Carbon 65, 35–45 (2013).

Park, J.-H. et al. Simple, green and clean removal of a poly (methyl methacrylate) film on chemical vapor deposited graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 171609, (2013).

Deokar, G. et al. Towards high quality CVD graphene growth and transfer. Carbon 89, 82–92 (2015).

Liang, X. et al. Toward clean and crackless transfer of graphene. ACS nano 5, 9144–9153 (2011).

Fang, T.-H. & Chang, W.-J. Nanomechanical properties of copper thin films on different substrates using the nanoindentation technique. Microelectron. Eng. 65, 231–238 (2003).

Bertolazzi, S., Brivio, J. & Kis, A. Stretching and breaking of ultrathin MoS2. ACS nano 5, 9703–9709 (2011).

Hu, W., Antoine, D. & Yu, X. Optically transparent poly(methyl methacrylate) composite reinforced by polyacylonitrile hollow nanofibers. J. Compos. Mater. 48, 3019–3024 (2013).

Jiang, H. et al. Finite deformation mechanics in buckled thin films on compliant supports. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 15607–15612 (2007).

Rice, C. et al. Raman-scattering measurements and first-principles calculations of strain-induced phonon shifts in monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 081307, (2013).

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Local strain engineering in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 13, 5361–5366 (2013).

Chakraborty, B. et al. Symmetry-dependent phonon renormalization in monolayer MoS2transistor. Phys. Rev. B 85, 161403, (2012).

Buscema, M., Steele, G. A., van der Zant, H. S. & Castellanos-Gomez, A. The effect of the substrate on the Raman and photoluminescence emission of single-layer MoS2. Nano Research 7, 561–571 (2014).

Conley, H. J. et al. Bandgap engineering of strained monolayer and bilayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 13, 3626–3630 (2013).

Peelaers, H. & Van de Walle, C. G. Effects of strain on band structure and effective masses in MoS 2. Phys. Rev. B 86, 241401, (2012).

Mak, K. F. et al. Tightly bound trions in monolayer MoS2. Nat. Mater. 12, 207–211 (2013).

Mouri, S., Miyauchi, Y. & Matsuda, K. Tunable photoluminescence of monolayer MoS2 via chemical doping. Nano Lett. 13, 5944–5948 (2013).

Li, X.-L., Liu, J.-F. & Li, Y.-D. Low-temperature synthesis of large-scale single-crystal molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) nanobelts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 4832–4834 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (grant number: PolyU 252001/14E), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 61302045) and the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (grant numbers: 1-ZVCG, G-UC72). The authors would like to acknowledge the supports by the University Research Facility in Materials Characterization and Device Fabrication of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y. conceived the idea and supervised the project. Z.L., Y.Z. and C.Y. designed research method. Z.L., Y.Z., Y.T. and C.Y. analyzed data. Z.L., R.Z. and X.W. conducted the material growth and characterization. Z.L., Y.Z. and C.Z. performed the transfer process and characterization. All authors contributed to the writing and editing.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Z., Zhao, Y., Zhou, C. et al. Controllable Growth of Large–Size Crystalline MoS2 and Resist-Free Transfer Assisted with a Cu Thin Film. Sci Rep 5, 18596 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18596

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18596

This article is cited by

-

Low Ohmic contact resistance and high on/off ratio in transition metal dichalcogenides field-effect transistors via residue-free transfer

Nature Nanotechnology (2024)

-

Large-area synthesis of high electrical performance MoS2 by a commercially scalable atomic layer deposition process

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2023)

-

Defect repairing in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Single step growth of vertical MoS2 thin films by chemical vapor deposition for hydrogen evolution reaction

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2023)

-

Alloy-buffer-controlled van der Waals epitaxial growth of aligned tellurene

Nano Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.