Abstract

TWIST, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, has been indicated to play a critical role in the progression of numerous malignant disorders. Published data on the significance of TWIST expression in head and neck carcinoma (HNC) risk have yielded conflicting results. Thus, we conducted a quantitative meta-analysis to obtain a precise estimate of this subject. After systematic searching and screening, a total of fifteen studies using immunohistochemistry for TWIST detection were included. The results showed that TWIST positive expression rate in HNC tissues was higher than that in normal tissues. TWIST expression might have a correlation with clinical features such as low differentiation, advanced clinical stage, presence of lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis and local recurrence (P < 0.05) , but not with age, gender, T stage and smoking as well as drinking (P > 0.05). In addition, over-expression of TWIST was a prognostic factor for HNC (HR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.13–3.25). The data suggested that TWIST might play critical roles in cancer progression and act as a prognostic factor for HNC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

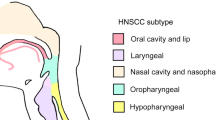

Head and neck carcinoma (HNC), the sixth most frequent kind of cancer worldwide, is a group of biologically similar cancers that originate from head and neck regions such as oral cavity, pharyngeal cavity and larynx1. Previous reports showed that life-style factors such as smoking, drinking, betel quid chewing, papilloma virus infection and exposure to toxic substances are possible etiological risk factors for HNC2,3. Besides, genetic variations might also play important roles in its genesis4. Hence, the etiological factors for this type of cancer are complicated. To find new biomarkers for predicting the prognosis of HNC patients is required.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a indispensable event for the formation of various organs during the process of embryonic development, whereas it may be suppressed for maintaining epithelial integrity in mature tissue5. Abnormal activation of EMT in epithelial tumors usually has been indicated to have a relationship with the genesis and development of a variety of cancers6.

Evidence shows that several transcriptional factors might act as inducers of EMT and thus play critical roles in its process. A basic helix-loop-helix (BHLH) transcription factor, TWIST, is one of the important EMT inducers. Reports showed that over-expression of TWIST might be associated with lymph node metastasis of thyroid cancer7 and gastric cancer8. In addition, TWIST act as a useful predictor of unfavorable prognosis for ovarian9 and renal cell carcinoma10. Hence, TWIST is involved not only in early events of malignancies, but contributes to cancer progression as well. Therefore, TWIST has been suggested as a potential target for cancer biotherapy and an important biomarker for predicting the prognosis of cancers11.

Previously, a growing body of studies has been conducted on the expression and significance of TWIST in HNC. However, the results were inconsistent. Since a single study was underpowered in demonstrating the roles of TWIST in HNC progression, we aimed to conduct a quantitative meta-analysis containing published data up to Jun 2015 that increased statistical power to get a more precise estimation. Since both TWIST1 and TWIST2 belong to the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcriptional factor family and they share more than 90% sequence homology and structural similarity at bHLH and C-teminal domains and biological similarity in disorders12, studies on TWIST, TWIST1 and TWIST2 were all considered in the present study.

Materials and Methods

Literature search strategy

An internet literature search was carried out in the databases such as Medline, Ovid, Springer, EMBASE and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) without a language limitation, covering all papers published up to Jun 2015. A combination of the following keywords was used: TWIST, EMT, head and neck neoplasm, tumor, cancer, pharynx, larynx and mouth. All searched studies were retrieved and the bibliographies were checked for other possible publications. Potential related review articles were hand searched to find additional eligible studies whenever necessary.

Inclusion criteria

Several criteria were used for the literature selection: first, studies must concern the roles of TWIST, TWIST1 or TWIST2 expression in primary HNC tissues and assess its relationship with pathological features and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used as the major method for detection of TWIST expression; second, papers should provide clinical data of cancer cases who were not subjected to radiotherapy or chemotherapy prior to the investigation; third, studies must be observationally designed. Accordingly, the exclusion criteria were used as follows: first, the judgment standard for positive TWIST expression was obviously different from other papers; second, TWIST was detected from the blood circulation of patients, or studies only concerned animal experiments or cell line cultures; third, reviews, duplicate publications, or papers presented insufficient information from which we could not infer the results.

Data extraction

Valuable information was carefully extracted from all eligible publications independently by two of the authors according to the inclusion criteria and illustrated in a database. For discrepancies of the data, a discussion was made to reach an agreement in case of conflicting evaluations. If a consensus were not reached, another author joined in to resolve the dispute and then a final decision was made by the majority of the votes.

Statistical analysis

The pooled odd ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI) was utilized to assess the relationship between TWIST expression and the clinicopathologic characteristics. Hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% CIs were used to evaluate the correlation between TWIST expression and the prognosis of patients with HNC, with its value of greater than 1 indicating poor outcome. HRs were directly extracted from the literature, estimated by the available information or estimated from the Kaplan-Meier curves according to the method raised by Tierney et al.13 if they were not directly reported in the primary literature. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed by a chi-square based Q statistic test. If a P value for a given Q-test was found to be more than 0.1, ORs were pooled according to a fixed-effect model (Mantel-Haenszel)14; otherwise, a random-effect model (DerSimonian and laird) was used15. Funnel plots16 were created to show the publication bias and a visually asymmetrical plot indicated a potential publication bias. The symmetry of the funnel plot was further determined by Egger’s linear regression test17. All statistical analysis was carried out by using the program STATA 11.0 software (Stata Corporation, Texas, USA).

Results

Study characteristics

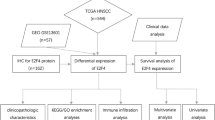

After a systematic search and screen, a total of sixty-nine publications were originally obtained, of which forty-two irrelevant papers were excluded. Thus, twenty-seven publications were eligible. Then, three review articles18,19,20 and one study in which IHC was not used21 were discarded. Next, one study that concerned cell line rather than tissue22 and seven papers that provided insufficient information23,24,25,26,27,28,29 were further excluded. Lastly, fifteen studies were selected for data extraction and evaluation30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 (Fig. 1).

Among the included studies, nine were written in English30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39, while the remaining six were in Chinese36,40,41,42,43,44. The relevant information was listed in Table 1. According to this table, the first author and the number and characteristics of cases for each study as well as other necessary information were presented. Notably, only six papers reported the prognostic data, of which information about HR were directly extracted from three studies31,32,38, while in the remaining three studies30,37,39, HRs were indirectly estimated from the Kaplan-Meier curves according to the method reported by Tierney et al.13. In a study by Qian et al.35, though HR value was reported, its relevant 95% CI and Kaplan-Meier curves were absent. Thus, the information about HR value in this paper was discarded.

Meta-analysis results

The main results of the present meta-analysis were presented in Table 2. For the overall data, the P value for the Q-test was 0.261 and thus, the between-study heterogeneity was insignificant and a fixed-effect model was selected for data pooling. However, heterogeneity could be shown in the subgroups regarding T stage, clinical stage, differentiation and lymph node metastasis, respectively. Therefore, random-effect models were used in these subgroups.

Positive expression of TWIST in HNC tissues were significantly higher than that in normal tissues (OR = 14.27, 95% CI = 8.22−24.79). As shown in this table, no association was found between TWIST expression and several clinicophathological features, such as age, gender, smoking, drinking and T stage. However, as shown in Fig. 2, TWIST over-expression was correlated with clinical stage (III + IV vs I + II, OR = 3.88, 95% CI = 2.04–7.37), differentiation (Low vs Moderate + High, OR = 2.12, 95% CI = 1.10–4.10) and local recurrence (Yes vs No, OR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.00–3.15), respectively, indicating that TWIST might have an association with advanced stages of HNC. In addition, TWIST over-expression has a correlation with lymph node metastasis (Yes vs No, OR = 3.40, 95% CI = 1.98–5.82) and distant metastasis (Yes vs No, OR = 5.67, 95% CI = 2.46–13.07), suggesting that TWIST might contribute to cancer development and progression (Fig. 3).

To evaluate the prognostic value of TWIST for HNC, HRs for the overall survival were pooled. As shown in Table 2, the pooled HR was 1.92 (95% CI = 1.13–3.25), suggesting that over-expression of TWIST was a prognostic factor for HNC (Fig. 4).

To determine the stability of the above comparisons, one-way sensitivity analysis45 was performed in the comparisons, respectively. Consequently, the statistical significance of the results was not changed when any one study was deselected (data not shown) in the repeated analysis, indicating the robustness of the results.

Bias diagnostics

Funnel plots were created to detect the possible publication bias. Then, Egger’s linear regression tests were used to assess the symmetries of the plots. The results showed that the publication bias was not significant for the pooled HRs comparison (t = 2.27, P > 0.05), indicating little effect of the publication bias on the overall results (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis, the pooled results from fifteen primary studies showed that TWIST expression might have an association with low differentiation, advanced clinical stage, presence of lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis and local recurrence, indicating that TWIST expression might play an important role in the development of HNC. In addition, TWIST might act as a prognostic factor for HNC.

HNC can severely affect the psychological health and life quality of patients because this type of cancer may directly influence speaking, eating and breathing due to its specific site. The underlying mechanisms of HNC development are not fully understood. Recently, much attention has been focused on EMT because it is representative of a transition in which cells lose their epithelial polarity and gain mesenchymal properties with increased mobility46. Based on this alteration, cancer cells become more malignant and have the tendency of being aggressive. The EMT process can be induced by a number of cytokines such as TGF-beta47, CTGF48 and HIF-1α, particularly in hypoxic microenvironment that resulted from excessive growth of cells49. Thus, EMT acts as a key event in the development of cancers and the critical molecules or signaling pathways involved in EMT have been regarded as potential targets for tumor biotherapy50. TWIST is one of the important inducers of EMT process. Several published meta-analyses have concerned the relationship of TWIST expression with cancers. For example, TWIST expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with lung cancer51 and oral cancer52. There were two meta-analyses published in 2014 have concerned the roles of TWIST in the prognosis of HNC and have generated conflicting results. One meta-analysis by Wushou et al.53 suggested that TWIST1 is a prognostic factor for HNC, with the value of the pooled HR 1.50 (95% CI:1.08–2.08). Nevertheless, the other one by Zhang et al.54 addressing the same issue showed that the HR for overall survival was 1.62 (95% CI: 0.78–3.38), indicating that TWIST may not be an unfavourable prognostic indicator in HNC. The discrepancy might be due to the reason that the criteria for literature inclusion were different and the number of the included studies regarding HNC was limited (only three) for these two meta-analyses, respectively. Additionally, the relationship between TWIST expression and clinical features had not been assessed. Hence, compared with these two published papers53,54, the greater number of the included studies with larger sample sizes in the present meta-analysis might increase power to get a more confidential estimate.

The precise molecular mechanisms of TWIST in cancer progression have not been fully demonstrated. As a BHLH factor, TWIST can regulate gene transcription by recognizing a unique spatial configuration of E-boxes55. Also, it promotes alteration of cells from the epithelial physiology to the mesenchymal phenotype56 and promotes prolonged TGF-β1-induced G2 arrest of cells, limiting the abilities of cells to repair and regenerate57. Therefore, the cancer cells become more malignant than before. Moreover, TWIST expression is positively correlated with increased microvessel density in cancers10,58, indicating that TWIST can promote angiogenesis possibly through up-regulation of various biological factors such as MMP-2, MMP-959 and VEGF60. Thus, neovascularization might obviously facilitate the migration of cancer cells. The above evidence might help explain the possible reasons why TWIST contributes to the cancer development such as lymph node and distant metastasis. However, future studies are warranted for clarifying the exact mechanisms because the published evidence is limited.

Evidence indicates that tobacco use has been shown to correlate with up-regulated TWIST expression61. Benzo(a)pyrene in tobacco might modulate TWIST expression and promote the migration and invasion of cancer cells62. Thus, the possible synergistic effects of smoking and TWIST expression are of great interest to investigators. In the present meta-analysis, four of the included studies assessed their association. Nevertheless, no associations were found in this comparison, possibly owing to the limited sample sizes. Moreover, the relationship between alcohol exposure and TWIST expression has also been evaluated. The data also failed to reveal a significant association between them. Thus, future studies considering smoking, drinking and other life-style factors are needed to explore the interactions of confounding factors with TWIST on cancer risk.

Survival information was available in six studies and nevertheless, the HR values could be extracted directly from three papers31,32,38 and indirectly estimated from the Kaplan-Meier curves in another three papers30,37,39. The pooled HRs for the overall survival showed a significant difference between TWIST positive cases and negative cases, indicating that patients with positive or high TWIST expression had a worse prognosis compared with that of the ones with negative or low TWIST expression. However, the results should be interpreted with caution because any subjective errors might exist when interpreting the curves.

The roles of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in the genesis of HNC have attracted much attention. HPV is a non-enveloped, double-stranded, epitheliotrophic, circular DNA virus that belongs to family Papovaviridae. Most cases of HPV positive HNC arise from the oropharyngeal region due to the possibility that this site is more vulnerable to epithelial injury and absence of protective keratin layer. HPV-positive HNCs have a favorable prognosis whereas HPV-negative ones exhibit a less favourable prognosis and a different molecular profile63, possibly because the former are primarily wild-type TP53, whereas HPV-negative tumors present mutated TP53 and show high chromosome instability64. Evidence indicates that HPV might also regulate TWIST expression and exert an effect on cancer progression65. However, the status of HPV infection has not been assessed in most of the included studies. Thus, the interaction of TWIST and HPV infection could not be determined in the present meta-analysis.

Several limitations might be included in this study. First, only published data in Chinese and English were involved. Papers included in other databases and published in other languages were ignored. Therefore, selection bias might exist. Second, the cut-off definition of TWIST appeared to be different in each study. This might affect the precision of the estimate. Third, the selected studies focused on TWIST expression in tissues rather than serum. Circulating prognostic markers have the tendency of being more convenient for detection. Fourth, heterogeneity might also be generated from the use of different anti-TWIST antibodies that were available from different companies, including rabbit or sheep polyclonal antibodies. This might exert an influence on the accuracy of TWIST detection. Fifth, most included studies in this meta-analysis concerned Chinese population and only a few concerned other ethnicities. Thus, the results might only be representative of a proportion of the people worldwide. Therefore, further well-designed investigations might be of value and interest for HNC research.

Despite the limitations, the data of the present meta-analysis showed a marked association of TWIST over-expression with low differentiation, advanced clinical stages, lymph node and distant metastasis as well as local recurrence, suggesting that TWIST might play critical roles in the development of HNC. In addition, TWIST over-expression might predict poor overall survival in patients with HNC. Future studies are needed to confirm the results.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhuo, X. et al. Is overexpression of TWIST, a transcriptional factor, a prognostic biomarker of head and neck carcinoma? Evidence from fifteen studies. Sci. Rep. 5, 18073; doi: 10.1038/srep18073 (2015).

References

van Nieuwenhuizen, A. J., Buffart, L. M., Brug, J., Leemans, C. R. & Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M. The association between health related quality of life and survival in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 51, 1–11 (2015).

Liao, C. T. et al. Clinical evidence of field cancerization in patients with oral cavity cancer in a betel quid chewing area. Oral Oncol. 50, 721–731 (2014).

Machiels, J. P. et al. Advances in the management of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. F1000Prime Rep. 6, 44 (2014).

Lacko, M. et al. Genetic susceptibility to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 89, 38–48 (2014).

Macara, I. G., Guyer, R., Richardson, G., Huo, Y. & Ahmed, S. M. Epithelial Homeostasis. Curr Biol. 24, R815–R825 (2014).

Steinestel, K., Eder, S., Schrader, A. J. & Steinestel, J. Clinical significance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Clin Transl Med. 3, 17 (2014).

Wang, N. et al. Overexpression of HIF-2alpha, TWIST and CXCR4 is associated with lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013, 589423 (2013).

Gao, X. H., Yang, X. Q., Wang, B. C., Liu, S. P. & Wang, F. B. Overexpression of twist and matrix metalloproteinase-9 with metastasis and prognosis in gastric cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 14, 5055–5060 (2013).

Kim, K. et al. The Role of TWIST in Ovarian Epithelial Cancers. Korean J Pathol. 48, 283–291 (2014).

Ohba, K. et al. High expression of Twist is associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7, 3158–3165 (2014).

Khan, M. A., Chen, H. C., Zhang, D. & Fu, J. Twist: a molecular target in cancer therapeutics. Tumour Biol. 34, 2497–2506 (2013).

Mao, Y. et al. Significance of heterogeneous Twist2 expression in human breast cancers. PLoS One. 7, e48178 (2012).

Tierney, J. F., Stewart, L. A., Ghersi, D., Burdett, S. & Sydes, M. R. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 8, 16 (2007).

Mantel, N. & Haenszel, W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 22, 719–748 (1959).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 7, 177–188 (1986).

Munafo, M. R., Clark, T. G. & Flint, J. Assessing publication bias in genetic association studies: evidence from a recent meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 129, 39–44 (2004).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 315, 629–634 (1997).

Smith, A., Teknos, T. N. & Pan, Q. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 49, 287–292 (2013).

Scanlon, C. S., Van Tubergen, E. A., Inglehart, R. C. & D’Silva, N. J. Biomarkers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in squamous cell carcinoma. J Dent Res. 92, 114–121 (2013).

Wu, K. J. & Yang, M. H. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness: the Twist1-Bmi1 connection. Biosci Rep. 31, 449–455 (2011).

Zhou, C. et al. Coexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha, TWIST2 and SIP1 may correlate with invasion and metastasis of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 41, 424–431 (2012).

Qiao, B., Chen, Z., Hu, F., Tao, Q. & Lam, A. K. BMI-1 activation is crucial in hTERT-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of oral epithelial cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 95, 57–61 (2013).

Sakamoto, K. et al. Overexpression of SIP1 and downregulation of E-cadherin predict delayed neck metastasis in stage I/II oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma after partial glossectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 19, 612–619 (2012).

Silva, B. S. et al. TWIST and p-Akt immunoexpression in normal oral epithelium, oral dysplasia and in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 17, e29–34 (2012).

de Freitas Silva, B. S., Yamamoto-Silva, F. P. & Pontes, H. A. & Pinto Junior Ddos, S. E-cadherin downregulation and Twist overexpression since early stages of oral carcinogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 43, 125–131 (2014).

Jia, J. et al. Epithelial mesenchymal transition is required for acquisition of anoikis resistance and metastatic potential in adenoid cystic carcinoma. PLoS One. 7, e51549 (2012).

Wu, T. et al. Increased expression of Lin28B associates with poor prognosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 8, e83869 (2013).

Horikawa, T. et al. Epstein-Barr Virus latent membrane protein 1 induces Snail and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 104, 1160–1167 (2011).

Jouppila-Matto, A. et al. Twist and snai1 expression in pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma stroma is related to cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 11, 350 (2011).

Song, L. B. et al. The clinical significance of twist expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 242, 258–265 (2006).

Fan, C. C. et al. Expression of E-cadherin, Twist and p53 and their prognostic value in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 139, 1735–1744 (2013).

Gasparotto, D. et al. Overexpression of TWIST2 correlates with poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oncotarget. 2, 1165–1175 (2011).

Lu, S. M. et al. Twist modulates lymphangiogenesis and correlates with lymph node metastasis in supraglottic carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl.). 124, 1483–1487 (2011).

Ou, D. L., Chien, H. F., Chen, C. L., Lin, T. C. & Lin, L. I. Role of Twist in head and neck carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Anticancer Res. 28, 1355–1359 (2008).

Qian, X. et al. Prognostic significance of ALDH1A1-positive cancer stem cells in patients with locally advanced, metastasized head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 140, 1151–1158 (2014).

Wang, B., Zhang, C., Zhang, S., Yue, K. & Wang, X. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transformation-Mediated Lymph Node Metastasis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Its Mechanism. Chin J Clin Oncol. 39, 1877–1885 (2012).

Liang, X. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha, in association with TWIST2 and SNIP1, is a critical prognostic factor in patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 47, 92–97 (2011).

Wushou, A. et al. Correlation of increased twist with lymph node metastasis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70, 1473–1479 (2012).

da Silva, S. D. et al. TWIST1 is a molecular marker for a poor prognosis in oral cancer and represents a potential therapeutic target. Cancer. 120, 352–362 (2014).

Hu, Z. & Cai, F. Expression and clinical significance of TWIST and Snail in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Military Med J South China. 15, 474–476 (2013).

Huang, Y. et al. Expression of TWIST protein, vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA and protein and their relation to biological characteristics of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin J Postgrad Med. 34, 30–33 (2011).

Zheng, J. & Nan, X. Expression and significance of TWIST in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Guide of China Med. 10, 212–213 (2012).

Gong, Z. & Yan, Y. Expression of Twist and E-cadherin in tongue squamous cell carcinoma and its clinical significance. Anhui Med Pharm J. 16, 941–943 (2012).

Zhu, Y., Yu, J. & Zhao, R. The expression of Twist, E-cadherin and N-cadherin in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin J Ophthalmol and Otorhinolaryngol. 14, 27–35 (2014).

Tobias, A. Assessing the influence of a single study in the meta-analysis estimate. Stata Techn Bull. 8, 15–17 (1999).

Pasquier, J., Abu-Kaoud, N., Al Thani, H. & Rafii, A. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in a Clinical Perspective. J Oncol. 2015, 792182 (2015).

Agajanian, M., Runa, F. & Kelber, J. A. Identification of a PEAK1/ZEB1 signaling axis during TGFbeta/fibronectin-induced EMT in breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 465, 606–612 (2015).

Zhu, X. et al. Epithelial derived CTGF promotes breast tumor progression via inducing EMT and collagen I fibers deposition. Oncotarget. 6, 25320–25338 (2015).

Yang, Y. J. et al. Hypoxia Induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Follicular Thyroid Cancer: Involvement of Regulation of Twist by Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1alpha. Yonsei Med J. 56, 1503–1514 (2015).

Moyret-Lalle, C., Ruiz, E. & Puisieux, A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors and miRNAs: “Plastic surgeons” of breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 5, 311–322 (2014).

Zeng, J. et al. Prognostic value of Twist in lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 4, 236–241 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. Over-expression of TWIST, an epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer, predicts poor survival in patients with oral carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 8, 9239–9247 (2015).

Wushou, A., Hou, J., Zhao, Y. J. & Shao, Z. M. Twist-1 up-regulation in carcinoma correlates to poor survival. Int J Mol Sci. 15, 21621–21630 (2014).

Zhang, P. et al. Prognostic role of Twist or Snail in various carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 44, 1072–1094 (2014).

Chang, A. T. et al. An evolutionarily conserved DNA architecture determines target specificity of the TWIST family bHLH transcription factors. Genes Dev. 29, 603–616 (2015).

Gonzalez, D. M. & Medici, D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 7, re8 (2014).

Lovisa, S. et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induces cell cycle arrest and parenchymal damage in renal fibrosis. Nat Med. 21, 998–1009 (2015).

Zhuo, X. et al. Expression and clinical significance of microvessel density and its association with TWIST in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 8, 1265–1270 (2015).

Che, N. et al. The role of Twist1 in hepatocellular carcinoma angiogenesis: a clinical study. Hum Pathol. 42, 840–847 (2011).

Lei, P. et al. Expression profile of Twist, vascular endothelial growth factor and CD34 in patients with different phases of osteosarcoma. Oncol Lett. 10, 417–421 (2015).

Fondrevelle, M. E. et al. The expression of Twist has an impact on survival in human bladder cancer and is influenced by the smoking status. Urol Oncol. 27, 268–276 (2009).

Wang, Y., Zhai, W., Wang, H., Xia, X. & Zhang, C. Benzo(a)pyrene promotes A549 cell migration and invasion through up-regulating Twist. Arch Toxicol. 89, 451–458 (2015).

Nishat, R., Behura, S. S., Ramachandra, S., Kumar, H. & Bandyopadhyay, A. Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Induced Head & Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Retrospect. J Clin Diagn Res. 9, ZE01–04 (2015).

Fakhry, C. et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 100, 261–269 (2008).

Liu, Y. et al. The indicative function of Twist2 and E-cadherin in HPV oncogene-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of cervical cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 33, 639–650 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. and Q.Z. designed and planned the experiment; X.Z., H.L. and A.C. wrote the manuscript draft; D.L. and H.Z. processed data and prepared the Figures and tables. X.Z. and H.L contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, X., Luo, H., Chang, A. et al. Is overexpression of TWIST, a transcriptional factor, a prognostic biomarker of head and neck carcinoma? Evidence from fifteen studies. Sci Rep 5, 18073 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18073

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18073

This article is cited by

-

Detection of Distant Metastases in Head and Neck Cancer: Changing Landscape

Advances in Therapy (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.