Abstract

This study aimed to determine the optimal fraction scheme (FS) in patients with small peripheral non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) with the 4 × 12 Gy scheme as the reference. CT simulation data for sixteen patients diagnosed with primary NSCLC or metastatic tumor with a single peripheral lesion ≤3 cm were used in this study. Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) plans were designed based on ten different FS of 1 × 25 Gy, 1 × 30 Gy, 1 × 34 Gy, 3 × 15 Gy, 3 × 18 Gy, 3 × 20 Gy, 4 × 12 Gy, 5 × 12 Gy, 6 × 10 Gy and 10 × 7 Gy. Five different radiobiological models were employed to predict the tumor control probability (TCP) value. Three other models were utilized to estimate the normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) value to the lung and the modified equivalent uniform dose (mEUD) value to the chest wall (CW). The 1 × 30 Gy regimen is recommended to achieve 4.2% higher TCP and slightly higher NTCP and mEUD values to the lung and CW compared with the 4 × 12 Gy schedule, respectively. This regimen also greatly shortens the treatment duration. However, the 3 × 15 Gy schedule is suggested in patients where the lung-to-tumor volume ratio is small or where the tumor is adjacent to the CW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retrospective studies have established that stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) treatment is effective for medically inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)1,2,3. SBRT can reportedly achieve disease-free survival (DFS), local control (LC) and distant control (DC) outcomes similar to those of surgery with minimal associated toxicity4,5,6.

Although SBRT has been widely used for the treatment of early-stage NSCLC7,8,9,10, the optimal fraction scheme (FS) has remained unclear. The FS in the literature varies extensively, from 1×2511,12,13 to 3×20 Gy8,14,15 and the corresponding biologically effective dose (BED) ranges from 87.5 to 180 Gy, using a α/β ratio of 10. Higher dose schedules will increase acute toxicities to normal tissues. Additionally, previous studies have only used overall survival (OS) or LC as endpoints when assessing the dose-response relationship with clinical outcomes; however, these studies failed to consider complications that may arise in normal tissues. Consequently, the optimal FS to maintain tumor control and to minimize toxicity for NSCLC patients requires further investigation.

Radiobiological modeling has the potential to link the dosimetric differences with radiobiological responses; this approach was recently used to predict the possibility of dose escalation for patients with esophageal cancer16 and primary prostate cancer17.

This study aimed to determine the optimal FS by radiobiologically modeling the tumor control probability (TCP) and normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) values of SBRT treatment of NSCLC, taking the 4×12 Gy scheme as a reference. To exclude the impact of tumor size, we only recruited patients bearing T1 or metastatic (≤3 cm) tumors for this study.

Methods and Materials

Ethics statement

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College. Because this is not a treatment-based study, our institutional review board waived the need for written informed consent from the participants. However, the patient information was kept anonymous to protect their confidentiality. The methods in the study were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations.

Patient characteristics and CT scanning

CT simulation data for sixteen patients previously diagnosed with primary or metastatic NSCLC who harbored single peripheral lesions ≤3cm were used in this study. The patient characteristics were presented in Table 1. The median tumor diameter was 2.3 cm and the median tumor volume was 4.9 cc. The patients were simulated in the supine position with a vacuum bag (Medtec Medical, Inc. Buffalo Grove, IL) or a thermoplastic mask (Guangzhou Klarity Medical & Equipment Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China) restriction system. Twelve of the sixteen patients underwent respiratory-correlated four-dimensional computed tomography (4DCT) scans using Brilliance CT with Big Bore (Cleveland, OH, USA). For the remaining four patients, respiratory motion was determined on a patient-specific basis in each of the three dimensions while considering respiratory motion, which was visualized with the aid of fluoroscopy due to the patients’ refusal. CT images were obtained at a 3 mm thickness during scanning. The CT images were then transferred to an Eclipse treatment planning system (Version 10.0, Varian Medical System, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) for target delineating, organs at risk (OARs) contouring and treatment planning.

Delineation of target volume and OARs

For 4DCT images, the internal target volume (ITV) was defined as the combination of the gross tumor volume (GTV) on the ten phases of the 4DCT scan under the CT pulmonary windows. For the 3DCT images, the ITV was expanded according to the tumor motion on fluoroscopy. To account for set-up uncertainties and potential baseline tumor shift, a planning target volume (PTV) was created by adding a uniform 5 mm margin expansion to the ITV. For normal tissue contouring, the whole lung was limited to the air-inflated lung parenchyma and the GTV and trachea/ipsilateral bronchus were excluded according to the RTOG 0915 report18. The chest wall (CW) was segmented from the corrected lung edges with a 2 cm expansion in the lateral, anterior and posterior directions, excluding the lung volume and the mediastinal soft tissue19,20,21. If the 2 cm expansion extended outside the body, then the contour extended only as far as the external patient surface20. To avoid cumbersome contouring of the entire CW, we defined it within a 3 cm limit in the head-to-feet direction from the PTV19.

Treatment planning

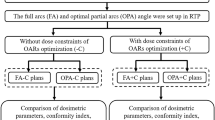

Ten different FS of 1 × 25 Gy, 1 × 30 Gy, 1 × 34 Gy, 3 × 15 Gy, 3 × 18 Gy, 3 × 20 Gy, 4 × 12 Gy, 5 × 12 Gy, 6 × 10 Gy and 10 × 7 Gy were prescribed according to previous publications. The treatment was planned using the Eclipse treatment planning system and conducted on the averaged 4DCT. All plans were designed on a TrueBeam LINAC with a 6 MV flattening filter free (FFF) photon beam and a maximum dose rate of 1400 MU/min. Plans were created using dual partial arcs to prevent irradiation of the contralateral lung. The collimator angles for all plans were set to 30° for one arc and 330° for the other arc to minimize the contribution of the tongue-and-groove effect to the dose. Optimization was conducted using the progressive resolution optimizer (PRO_10028) algorithm implemented in Eclipse 10.0. The optimizing objectives were adjusted to ensure that the maximum dose was between 120%–130% of the prescription dose and centered in the GTV. Dose calculation was performed using the anisotropic analytical algorithm (AAA_10028) with a grid resolution of 1 mm while accounting for the heterogeneity correction. The final dose was normalized to ensure that 95% of the PTV received the prescription dose. All prescription dose constraints and critical organ dose-volume limits met the criteria of the RTOG 0915 protocol18 and other publications22.

Radiobiological modeling

Both the TCP and NTCP values were calculated using in-house developed programs with MATLAB 7.0 (MathWorks, USA). The TCP was calculated using five different radiobiological models: the Martel model, Fenwick model, Webb-Nahum model, equivalent uniform dose (EUD)-based model and Nitin model. The Webb-Nahum model is a general-type of model with modeling parameters originating from in vitro experiments using lung cancer cell lines, whereas the parameters of the other four models are based on the results of clinical trials on lung cancer. Notably, the Nitin model was generated by retrospectively analyzing 504 NSCLC tumors treated with a variety of SBRT schedules23. We used the EUD based Lyman-Kutcher-Burman (LKB) model and Fenwick model to estimate the NTCP value to the lung. Radiation-induced CW toxicities were predicted using the modified equivalent uniform dose (mEUD) model with moderate weighting24. The specific calculation procedure was as follows: first, the statistics from a cumulative dose volume histogram (cDVH) of the GTV, lung and CW were exported at a resolution of 5 cGy and imported into MATLAB software. Second, the in-house developed program converted the cDVH to the differential DVH (dDVH) according to Gay’s method25. Third, the program converted the dose in each volume element to a biologically equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) using the formula reported by other publications26,27. Finally, the main program automatically calculated the TCP and NTCP results using different radiobiological models. The value of α/β ratio was assigned to 10 Gy for the tumor (an appropriate value for lung tumor) during the EQD2 and BED conversion15,28. α/β values of 1.3 and 3 Gy were assigned to estimate the NTCP to the lung and the mEUD to the CW, respectively29,30. We used the formula BED10 = n×d×[1 + d/(α/β)] to determine the relationship between BED10 and dose-response. n and d represent the number of fractions and dose per fraction, respectively, as described by Liu’s work28.

The following five TCP predicting models were taken from the literatures:

The Martel model31

where Di is the uniform dose irradiated to the fractional volume Vi. D50 (the dose needed to achieve a 50% probability of tumor control) = 84.5 Gy and γ (the normalized slope of the sigmoid-shaped dose response curve at D50) = 1.5, giving local progression-free survival at 30 months;

The Fenwick model in TCP prediction32

where D50 = 84.6 Gy, m = 0.329, c = 9.58, V is the tumor volume in cm3 and Φ is a Gaussian integral;

The Webb-Nahum model33

where αm = 0.30 and σα = 0.11, αm and σα are calculated by averaging ten different histological sub-types of human lung cancer cell lines from Carmichael’s report34. ρ = 108 is the density of clonogenic cells in the tumor35 and v is the tumor volume in cm3;

TCP was calculated for each of the i volume bins Vi of DVH using Equation (1), (2) and (3) and combined using the standard approach.

The EUD model25

where TCD50(the tumor dose to control 50% of the tumor) = 51.24 Gy and γ50 (the change in TCP expected because of a 1% change in dose about the TCD50) = 0.83 is obtained from Okunieff’s report of a multi-institutional analysis36. α = 0.30. Di is the uniform dose irradiated to the fractional volume Vi;

The Nitin model23

where BED10 is the BED calculated using the linear quadratic (LQ) model with α/β = 10 Gy and c, TCD50 and k are 10 Gy/cm, 0 Gy and 31 Gy, respectively. L is the maximal tumor diameter;

The following three NTCP predicting models were also taken from the literatures:

The LKB model37

where n = 1.00, m = 0.45 and TD50 = 26.838. Di is the uniform dose irradiated to the fractional volume Vi;

The Fenwick model in NTCP prediction32

where D is mean lung dose and Φ is the integrated normal distribution;

The mEUD model24

where N is the total number of dose bins, di is the fractional dose for the subvolume of Vi of the 100 cc high-dose region in the DVH. Di is total dose of the 100cc dDVH. α = 5 (moderate weighting). The numerator C is a constant.

Determining the optimal FS

As no consistent criterion for evaluating the optimal FS exists, we use the 4 × 12 Gy schedule as a referential FS because it is the most commonly used dose schedule when the tumor is less than 3 cm39,40,41 and extensive publications have demonstrated its safety, efficacy and minimal toxicity for SBRT treatment of lung cancer8,42,43,44. Therefore, the optimal FS in this study is defined as the FS with TCP and NTCP values comparable to the 4 × 12 Gy dose schedule while providing the fewest fractions.

Statistical analysis

All data in this study are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD). Differences between plans were assessed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test in two related samples using SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL). Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Comparison of tumor BED10 values for different FS

The calculated tumor BED10 (with a α/β ratio of 10) values for 1 × 25 Gy, 1 × 30 Gy, 1 × 34 Gy, 3 × 15 Gy, 3 × 18 Gy, 3 × 20 Gy, 4 × 12 Gy, 5 × 12 Gy, 6 × 10 Gy and 10 × 7 Gy were listed in Table 2. The tumor BED10 values, in descending order, were 3 × 20 Gy > 3 × 18 Gy > 1 × 34 Gy > 5 × 12 Gy > 1 × 30 Gy = 6 × 10 Gy > 10 × 7 Gy > 3 × 15 Gy > 4 × 12 Gy > 1 × 25 Gy.

Effect of the tumor BED10 on the TCP and NTCP values

The calculated TCP and NTCP values in sixteen patients were also listed in Table 2. The difference in the TCP and NTCP values between either of the two FS was statistically significant (p < 0.05). TCP positively correlated with the tumor BED10 in five TCP radiobiological models. Additionally, the number of fractions also influenced the NTCP estimation of an equivalent tumor BED10. The 3 × 20 Gy scheme provided the highest TCP (98.2% on average), NTCP (13.3% on average for the lung) and mEUD values (179.0 on average for the CW), while the 1 × 25 scheme attained the lowest TCP (82.8% on average), NTCP (4.9% on average for the lung) and mEUD values (90.4 on average for the CW). The cDVH for the GTV, lung and CW from ten regimens after EQD2 conversion were presented in Fig. 1. The EQD2-based cDVH reflected the difference of EQD2 irradiated to the tumor and normal tissues.

Determination of the optimal FS

When R > 400 or D was between 5.5–15 mm, the 1×30 Gy schedule improved the TCP estimation by 4.2% (Table 2) and significantly reduced the fractionation while maintaining NTCP and mEUD values slightly higher to those for the 4×12 Gy regimen (Table 3, 6.0% vs 4.1% for the NTCP value to the lung and 80.7 vs 62.2 for the mEUD value to the CW). The 1×25 Gy schedule was excluded due to its much lower TCP value (82.8% on average) compared with the 4×12 Gy scheme (89.9% on average).

Conversely, when R ≤ 400 and D ≥ 15 or when D ≤ 5.5 mm, the 3 × 15 Gy scheme was recommended due to the 2.2% higher TCP prediction (Table 2) and only slightly higher NTCP and mEUD values to the lung and CW, respectively (Table 3, 13.4% vs 10.9% for the NTCP value to the lung and 142.9 vs 127.1 for the mEUD value to the CW). All the NTCP and mEUD comparisons between either of the two FS were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Although the 6×10 and 10×7 Gy FS predicted even higher TCP values and comparable NTCP and mEUD values, these schemes required more fractionation than the 3×15 Gy scheme and were thus not recommended.

Discussion

Our analysis of the calculated TCP and NTCP values for lung tumors (≤3cm) using radiobiological modeling suggested that a higher BED10 is associated with improved TCP and that the NTCP to the lung and mEUD value to the CW are influenced by both the BED10 and number of fractions. We determined the most optimal FS were 1×30 and 3×15 Gy for different tumor locations in patients with peripheral NSCLC whose lesions are ≤3cm. To our knowledge, our study is the first to use radiobiological models to predict the TCP and NTCP values from ten FS for SBRT treatment of lung cancer.

Radiation pneumonitis (RP) and radiation-related CW toxicities are the two most common radiotherapy-induced side effects in patients with NSCLC undergoing SBRT. The incidence of RP and CW toxicities range from 10% to 20.3%45,46,47,48 and from 8.3% to 32.8%21,24,49,50,51,52, respectively. A systematic review of 3201 patients with localized stage I NSCLC treated with SBRT revealed 2-year OS and LC values of 70% and 91%4, respectively; therefore, the impact of radiation-related complications on the quality of life of these patients warrants further attention. Based on our analysis of the ten dose schedules, we recommend the use of the 1×30 and 3×15 Gy regimens for the treatment of patients with peripheral NSCLC whose tumors are ≤3cm because this strategy results in comparable NTCP values while shortening the treatment duration compared with the 4×12 Gy dose schedule.

Our radiobiological modeling is consistent with the results of previous retrospective analyses of the dose response for lung SBRT using large sample sizes. (1) Onishi et al. observed that BED10 ≥ 100 Gy significantly improved both LC and 3-year OS in a cohort of 245 patients from multiple Japanese institutions53 and other studies further confirmed this finding7,8. The 7.1% increase (4 × 12 Gy vs 1 × 25 Gy) in the absolute value of the TCP for a BED10 of 105.6 Gy observed in this study supports the findings of several clinical investigations; however, the improvement predicted in our study was smaller due to the use of different tumor stages and various fraction regimens in other clinical studies. (2) Videtic et al. reviewed the outcomes of 2 SBRT schedules (30 Gy and 34 Gy) for 80 patients with medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. Both regimens provided equivalent LC and OS rates54. We observed that the 1×34 Gy schedule provided a median improvement of only 3% in the predicted TCP compared with the 1×30 Gy scheme, an improvement too small to be detected in the 80 patients in Videtic’s study. Moreover, the 3.7% absolute increase in toxicities to the lung and the 27.9% relative increase in toxicities to the CW that were predicted in our study for the 1×34 Gy schedule are consistent with the 7.3% and 16.0% of patients who experienced toxicity in response to 30 Gy and 34 Gy in their study, although this difference was not significant. (3) A recent clinical study conducted by Li et al. reported the use of 70 Gy in 10 fractions to achieve excellent LC while maintaining acceptable toxicities for NSCLC patients55. Our analysis also supports Li’s finding: the average TCP in response to the 10×7 Gy regimen was 92.9%, while the NTCP to the lung was only 4.3–5.2% in absolute value and the mEUD value to the CW was the second lowest in the 10 fraction regimens. (4) Stephans et al. noted that 60 Gy delivered in three fractions attained much higher rates of CW toxicity than 50 Gy delivered in five fractions (18% vs. 4%)49. The mEUD model predicted CW-related complications of 179.0 and 103.7 on average for the 3×20 Gy and 6×10 Gy schedules in our study, respectively, indicating an up to 72.6% relative reduction in CW-related complications for multiple fraction regimens. The 5 × 10 Gy scheme in Stephans’s research will likely further reduce the rate of complications. Other studies have also reported the tendency that increasing the number of fractions tended to lower the risk of CW pain (CWP)21,24,50,51. Our results are consistent with the results of the above-mentioned clinical studies, indicating that SBRT treatment for patients with NSCLC can be predicted using our models.

Although a calculated BED10 ≥ 100 Gy is generally associated with improved outcomes, the benefit and need for BED10 values higher than 120 Gy or 150 Gy have not yet been determined in small tumors (≤3 cm)10,15. Our results for patients with small tumors (≤3 cm) demonstrated that a BED10 of 120–130 Gy was sufficient to achieve a TCP of 92.9–95.2% while maintaining acceptable radiation-related toxicities to the lung and CW. Higher BED10 values (150–180 Gy) further improved the TCP (97.0–98.2%) but increased the NTCP to the lung by up to 9% in absolute value and increased the risk of radiation-related CW toxicities by up to 43% in relative value.

Radiobiological models can be used to calculate TCP and NTCP values with a focus on the dosimetric difference among different fraction regimens without involving unmeasured and potential confounders, such as pathological sub-type, age, sex and other radiation therapy uncertainties, such as set-up error and inter- or intrafractional tumor motion that will influence the outcome of the clinical treatment. We believe the proposed method facilitated the comparison of the dose responses of different radiotherapy fraction regimens. However, the application of radiobiological models is somewhat controversial, particularly for hypofractionated radiation therapy. Park et al. demonstrated that the universal survival curve (USC) better approximated the experimentally measured survival curves in the ablative, high-dose range than the LQ model beyond the threshold of 6.2 Gy per fraction56. However, no publication has shown that the USC can predict clinical datasets for SBRT better than standard models up till now and the utility of a purely empirical model with an additional adjustable parameter for predicting in vitro data is questionable. Conversely, accumulating clinical evidence has confirmed the accuracy of LQ-based TCP and BED models. Guckenberger et al. suggested that the traditional LQ formalism accurately modeled for patients with stage I NSCLC undergoing SBRT based on 395 patients from 13 German and Austrian centers57. Shuryak et al. also found that LQ-based TCP and BED models can provide significantly better fits to local control data for NSCLC than TCP models using other high-dose models58. According to the clinical evidence, we believe that the data acquired in our study utilizing the LQ model are reliable.

Our study has several limitations. (1) The TCP and NTCP values in the study were predicted by radiobiological models, without considering the repopulation and reoxygenation of the tumor cells during the treatment course and may not reflect actual clinical tumor control and normal tissue complications. However, we assume that the proposed method feasibly predicts the radiobiological response, because the outcomes of this study are consistent with other retrospective SBRT studies of lung cancer. Furthermore, different radiobiological models predicted similar trends, irrespective of the TCP or NTCP prediction. (2) We did not consider radiation-induced rib fracture, which is one of the common complications of lung SBRT. Although several reports concluded that the tumor-chest wall distance is a risk factor for this complication59, no radiobiological model has been proposed to predict the incidence of rib fracture; thus, we could not easily evaluate rib fracture during the modeling.

Conclusions

Different radiobiological models yield consistent predictions of TCP and NTCP values for different FS. Higher BED schemes improve the TCP and increasing the number of fractions beneficially reduces the NTCP and mEUD values. The 1 × 30 Gy regimen is preferred to achieve 4.2% higher TCP value and slightly higher NTCP and mEUD values to the lung and CW, respectively, while shortening the treatment duration compared with the 4 × 12 Gy schedule for patients with peripheral NSCLC tumors ≤3 cm. However, the 3 × 15 Gy regimen is recommended in certain patients where the lung-to-tumor volume ratio is small or where the tumor is adjacent to the CW.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Huang, B.-T. et al. Radiobiological modeling analysis of the optimal fraction scheme in patients with peripheral non-small cell lung cancer undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy. Sci. Rep. 5, 18010; doi: 10.1038/srep18010 (2015).

References

Xia, T. et al. Promising clinical outcome of stereotactic body radiation therapy for patients with inoperable Stage I/II non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 66, 117–125 (2006).

Baumann, P. et al. Outcome in a prospective phase II trial of medically inoperable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 27, 3290–3296 (2009).

Timmerman, R. et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 303, 1070–1076 (2010).

Solda, F. et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy (SABR) for the treatment of primary non-small cell lung cancer; systematic review and comparison with a surgical cohort. Radiother Oncol. 109, 1–7 (2013).

Zheng, X. et al. Survival outcome after stereotactic body radiation therapy and surgery for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 90, 603–611 (2014).

Zhang, B. et al. Matched-pair comparisons of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) versus surgery for the treatment of early stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 112, 250–255 (2014).

Guckenberger, M. et al. Dose-response relationship for image-guided stereotactic body radiotherapy of pulmonary tumors: relevance of 4D dose calculation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 74, 47–54 (2009).

Kestin, L. et al. Dose-response relationship with clinical outcome for lung stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) delivered via online image guidance. Radiother Oncol. 110, 499–504 (2014).

Olsen, J. R. et al. Dose-response for stereotactic body radiotherapy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 81, e299–303 (2011).

Park, S. et al. Analysis of biologically equivalent dose of stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary and metastatic lung tumors. Cancer Res Treat. 46, 403–410 (2014).

Le, Q. T. et al. Results of a phase I dose-escalation study using single-fraction stereotactic radiotherapy for lung tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 1, 802–809 (2006).

Li, R. et al. Clinical implementation of intrafraction cone beam computed tomography imaging during lung tumor stereotactic ablative radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 87, 917–923 (2013).

Huang, B. T. et al. Comparison of Two RapidArc Delivery Strategies in Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy of Peripheral Lung Cancer with Flattening Filter Free Beams. PLoS One. 10, e0127501 (2015).

Stephans, K. L. et al. A comparison of two stereotactic body radiation fractionation schedules for medically inoperable stage I non-small cell lung cancer: the Cleveland Clinic experience. J Thorac Oncol. 4, 976–982 (2009).

Koshy, M., Malik, R., Weichselbaum, R. R. & Sher, D. J. Increasing radiation therapy dose is associated with improved survival in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiation therapy for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 91, 344–350 (2015).

Warren, S. et al. Radiobiological determination of dose escalation and normal tissue toxicity in definitive chemoradiation therapy for esophageal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 90, 423–429 (2014).

Kuang, Y. et al. Volumetric modulated arc therapy planning for primary prostate cancer with selective intraprostatic boost determined by 18F-choline PET/CT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 91, 1017–1025 (2015).

RADIATION THERAPY ONCOLOGY GROUP. A Randomized Phase II Study Comparing 2 Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) Schedules for Medically Inoperable Patients with Stage I Peripheral Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. (2012). Available at: http://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0915. (Accessed: 12th August 2015).

Kong, F. M. et al. Consideration of dose limits for organs at risk of thoracic radiotherapy: atlas for lung, proximal bronchial tree, esophagus, spinal cord, ribs and brachial plexus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 81, 1442–1457 (2011).

Mutter, R. W. et al. Dose-volume parameters predict for the development of chest wall pain after stereotactic body radiation for lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 82, 1783–1790 (2012).

Dunlap, N. E. et al. Chest wall volume receiving >30 Gy predicts risk of severe pain and/or rib fracture after lung stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 76, 796–801 (2010).

Martin, A. & Gaya, A. Stereotactic body radiotherapy: a review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 22, 157–172 (2010).

Ohri, N. et al. Modeling local control after hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a report from the elekta collaborative lung research group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 84, e379–384 (2012).

Woody, N. M. et al. Predicting chest wall pain from lung stereotactic body radiotherapy for different fractionation schemes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 83, 427–434 (2012).

Gay, H. A. & Niemierko, A. A free program for calculating EUD-based NTCP and TCP in external beam radiotherapy. Phys Med. 23, 115–125 (2007).

Partridge, M., Ramos, M., Sardaro, A. & Brada, M. Dose escalation for non-small cell lung cancer: analysis and modelling of published literature. Radiother Oncol. 99, 6–11 (2011).

van Baardwijk, A. et al. Is high-dose stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) overkill? A systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 105, 145–149 (2012).

Liu, L., Bassano, D. A., Prasad, S. C., Hahn, S. S. & Chung, C. T. The linear-quadratic model and fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 57, 827–832 (2003).

Scheenstra, A. E. et al. Alpha/beta ratio for normal lung tissue as estimated from lung cancer patients treated with stereotactic body and conventionally fractionated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 88, 224–228 (2014).

Fowler, J. F., Tome, W. A., Fenwick, J. D. & Mehta, M. P. A challenge to traditional radiation oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 60, 1241–1256 (2004).

Martel, M. K. et al. Estimation of tumor control probability model parameters from 3-D dose distributions of non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 24, 31–37 (1999).

Fenwick, J. D. et al. Escalation and intensification of radiotherapy for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: opportunities for treatment improvement. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 21, 343–360 (2009).

Webb, S. & Nahum, A. E. A model for calculating tumour control probability in radiotherapy including the effects of inhomogeneous distributions of dose and clonogenic cell density. Phys Med Biol. 38, 653–666 (1993).

Carmichael, J. et al. Radiation sensitivity of human lung cancer cell lines. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 25, 527–534 (1989).

Lindblom, E. et al. Treatment fractionation for stereotactic radiotherapy of lung tumours: a modelling study of the influence of chronic and acute hypoxia on tumour control probability. Radiat Oncol. 9, 149 (2014).

Okunieff, P., Morgan, D., Niemierko, A. & Suit, H. D. Radiation dose-response of human tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 32, 1227–1237 (1995).

Luxton, G., Keall, P. J. & King, C. R. A new formula for normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) as a function of equivalent uniform dose (EUD). Phys Med Biol. 53, 23–36 (2008).

Seppenwoolde, Y. et al. Comparing different NTCP models that predict the incidence of radiation pneumonitis. Normal tissue complication probability. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 55, 724–735 (2003).

Allibhai, Z. et al. The impact of tumor size on outcomes after stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 87, 1064–1070 (2013).

Jain, S. et al. Lung stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) delivered over 4 or 11 days: a comparison of acute toxicity and quality of life. Radiother Oncol. 108, 320–325 (2013).

Mangona, V. S. et al. Toxicity after central versus peripheral lung stereotactic body radiation therapy: a propensity score matched-pair analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 91, 124–132 (2015).

Nagata, Y. et al. Clinical outcomes of a phase I/II study of 48 Gy of stereotactic body radiotherapy in 4 fractions for primary lung cancer using a stereotactic body frame. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 63, 1427–1431 (2005).

Kelley, K. D. et al. Medically inoperable peripheral lung cancer treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol. 10, 120 (2015).

Shibamoto, Y. et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy using a radiobiology-based regimen for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: five-year mature results. J Thorac Oncol. 10, 960–964 (2015).

Bongers, E. M. et al. Predictive parameters of symptomatic radiation pneumonitis following stereotactic or hypofractionated radiotherapy delivered using volumetric modulated arcs. Radiother Oncol. 109, 95–99 (2013).

Baker, R. et al. Clinical and dosimetric predictors of radiation pneumonitis in a large series of patients treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy to the lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 85, 190–195 (2013).

Matsuo, Y. et al. Dose—volume metrics associated with radiation pneumonitis after stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 83, e545–549 (2012).

Kanemoto, A., Matsumoto, Y. & Sugita, T. Timing and characteristics of radiation pneumonitis after stereotactic body radiotherapy for peripherally located stage I lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 20, 680–685 (2015).

Stephans, K. L. et al. Prediction of chest wall toxicity from lung stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 82, 974–980 (2012).

Lagerwaard, F. J., Haasbeek, C. J., Smit, E. F., Slotman, B. J. & Senan, S. Outcomes of risk-adapted fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 70, 685–692 (2008).

Coroller, T. P. et al. Low incidence of chest wall pain with a risk-adapted lung stereotactic body radiation therapy approach using three or five fractions based on chest wall dosimetry. PLoS One. 9, e94859 (2014).

Creach, K. M. et al. Dosimetric predictors of chest wall pain after lung stereotactic body radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 104, 23–27 (2012).

Onishi, H. et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (HypoFXSRT) for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: updated results of 257 patients in a Japanese multi-institutional study. J Thorac Oncol. 2, S94–100 (2007).

Videtic, G. M. et al. 30 Gy or 34 Gy? Comparing 2 single-fraction SBRT dose schedules for stage I medically inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 90, 203–208 (2014).

Li, Q. et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) using 70 Gy in 10 fractions for non-small cell lung cancer: exploration of clinical indications. Radiother Oncol. 112, 256–261 (2014).

Park, C., Papiez, L., Zhang, S., Story, M. & Timmerman, R. D. Universal survival curve and single fraction equivalent dose: useful tools in understanding potency of ablative radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 70, 847–852 (2008).

Guckenberger, M. et al. Applicability of the linear-quadratic formalism for modeling local tumor control probability in high dose per fraction stereotactic body radiotherapy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 109, 13–20 (2013).

Shuryak, I., Carlson, D. J., Brown, J. M. & Brenner, D. J. High-dose and fractionation effects in stereotactic radiation therapy: Analysis of tumor control data from 2965 patients. Radiother Oncol. 115, 327–334 (2015).

Nambu, A. et al. Rib fracture after stereotactic radiotherapy for primary lung cancer: prevalence, degree of clinical symptoms and risk factors. BMC Cancer. 13, 68 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A2015534) and Shantou University Medical College Clinical Research Enhancement Initiative (201424) and Cooperative and Creative Center, Shantou University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.T.H. conceived, designed the experiments and wrote the paper. J.Y.L. and J.Z.C. performed the experiments and collected the data. P.X.L. analyzed the data. D.R.L. and C.Z.C. revised the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, BT., Lu, JY., Lin, PX. et al. Radiobiological modeling analysis of the optimal fraction scheme in patients with peripheral non-small cell lung cancer undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy. Sci Rep 5, 18010 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18010

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18010

This article is cited by

-

Dosimetric comparison and biological evaluation of fixed-jaw intensity-modulated radiation therapy for T-shaped esophageal cancer

Radiation Oncology (2021)

-

Different definitions of esophagus influence esophageal toxicity prediction for esophageal cancer patients administered simultaneous integrated boost versus standard-dose radiation therapy

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.