Abstract

Three very different records are combined here to reconstruct the evolution of environments in the Cantabrian Region during the Upper Pleistocene, covering ~35.000 years. Two of these records come from Antoliñako Koba (Bizkaia, Spain), an exceptional prehistoric deposit comprising 9 chrono-cultural units (Aurignacian to Epipaleolithic). The palaeoecological signal of small-vertebrate communities and red deer stable-isotope data (δ13C and δ15N) from this mainland site are contrasted to marine microfaunal evidence (planktonic and benthic foraminifers, ostracods and δ18O data) gathered at the southern Bay of Biscay. Many radiocarbon dates for the Antoliña’s sequence, made it possible to compare the different proxies among them and with other well-known North-Atlantic records. Cooling and warming events regionally recorded, mostly coincide with the climatic evolution of the Upper Pleistocene in the north hemisphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

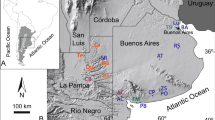

The reconstruction of past environments has been addressed from many disciplines and perspectives in the past, being fundamentally concerned with two things: a well-defined and reasonably complete environmental record and an adequate chronological framework. A holistic effort in this sense, is to be found at the recently published results of the INTIMATE project1. An extensive compilation of climatic and palaeoenvironmental reconstructions of the 60—8 ka period in the North Atlantic Region is presented therein, with authors using diverse records, as the Greenland ice-cores, tree-rings, pollen, tephrochronology, speleothems and marine proxies, among others. Independently, for the first time, we combine here radiometric dating with three very different proxies, i.e., small vertebrates, stable isotopes of herbivores and marine record (ostracods and foraminifers), commonly used each one of them separately2,3,4, to reconstruct the evolution of landscapes and environments in the Cantabrian Region (Fig. 1) during the Upper Pleistocene, covering a time span of ~35.000 years.

Geographical location.

(a) Antoliñako Koba site (Gautegiz-Arteaga, Bizkaia, Spain). (b) Marine cores taken at the outer Basque shelf (Southern Bay of Biscay). The figure was designed through the combined use of Macromedia Freehand MX, Adobe Illustrator CS6 and Adobe Photoshop Elements 12. Figures 1a and 1b were modified under permission from elsewhere3,28.

The first proxy is based on small vertebrates (Fig. 2). Digestion sub-products of birds of prey (i.e., rejection pellets) and small carnivores are the main sources for small-vertebrate deposition in archaeological sites5, being caves and rock shelters particularly propitious places for those animals to nest at the entrances, or to build burrows inside, respectively3,6,7. Unlike large mammal remains (many of them product of human selection), small-vertebrate accumulations reasonably well reflect local biocenosis, despite unavoidable filters due to specific predators5. Moreover, small vertebrates are particularly sensitive to climatic and habitat changes and their shifts along time in terms of taxa and number of specimens can be successfully used for the reconstruction of past environments3,6,7,8,9,10,11.

Selected specimens of small vertebrates from Antoliñako Koba (Gautegiz-Arteaga, Bizkaia, Spain).

Marmota marmota (1) right D4 in occlusal view; Apodemus sylvaticus (2) right M2 in occlusal view; A. flavicollis (3) left M2 in occlusal view; Eliomys quercinus (4) right M1 or M2 in occlusal view; Arvicola amphibius (5) right m1 in occlusal view; Pliomys lenki (6) right m1 in occlusal view; Microtus (Alexandromys) oeconomus (7) left m1 in occlusal view; Chionomys nivalis (8) right m1 in occlusal view; Microtus (Terricola) lusitanicus (9) right m1 in occlusal view; M. (Microtus) agrestis (10) right m1 in occlusal view; M. (M.) arvalis (11) left m1 in occlusal view; Neomyni indet. (12) left mandibular condyle in posterior view; Neomys sp. (13) right i1 in lateral view; Sorex cf. coronatus (14) incomplete left mandible with i1 (broken), a1 and p4; (15) left M1 in occlusal view; S. minutus (16) incomplete left mandible in medial view; Crocidura russula (17) right m1 in lateral view; Talpa sp. (18) left humerus in anterior view; Anguis fragilis (19) incomplete right maxillae in medial view; Coronella girondica (20) trunk vertebrae in ventral view; Vipera sp. (21) trunk vertebrae in ventral view; Rana gr. temporaria-iberica (22) sacral vertebrae in ventral view. Scale bar = 1 mm for figures 2–11, 13, 16 and 17; 2 mm for figures 1, 12, 14, 15 and 19–22; 4 mm for figure 18.

Another proxy is given by the analysis of the stable-isotope data from bone collagen of herbivores. Variability in climate and local environment determines food source availability and different food sources have particular stable carbon and nitrogen isotope values. Since the food isotopic signal is reflected in bone collagen, this can be used as a proxy to infer palaeodietary and palaeoclimatic variations12,13. The stable carbon isotope ratio (δ13C) of herbivore tissue is related to factors such as the environment, the photosynthetic pathways of consumed plant matter, humidity, water availability, salinity and partial atmospheric pCO214,15. For instance, plants in woody landscapes appear to lead to δ13C depletion compared to plants of open habitats (the so-called ‘canopy effect’16,17). By contrast, nitrogen isotope ratios (δ15N) preserved in animal tissues are related to factors such as diet, climate and water availability18,19,20,21. In addition, the δ15N of herbivores’ bone collagen may reflect processes of soil formation, especially in environments with influence of permafrost19,20,22. During cold periods, the δ15N in the collagen of herbivores shows lower values and thereafter, from a diachronic standpoint, an increase of δ15N values over time may be due to temperature rising parallel to higher organic activity in soils19,20,22,23. As plant δ13C and δ15N signals reflect environmental parameters and isotope variations occur during periods of great climatic change, variations in collagen isotope values reflect the effects that the environment may have had on fauna19,20,21,22,23,24.

The marine record, represented here by planktonic and benthic foraminifers and ostracods gathered at the southern Bay of Biscay (Fig. 3), not so far from Antoliñako Koba site (see Fig. 1 and Methods), has been extensively used for palaeoenvironmental reconstructions in the Quaternary period4,25,26,27,28. The planktonic foraminifer Neogloquadrina pachyderma sinistral (sin), in particular, is a polar species that appears in percentages of >90% to the north of the North Atlantic Polar Front29, being its abundance a useful proxy to identify the meridional migration of the Polar Front during the Quaternary. In the western Iberian Margin, high quantities of this taxon are connected to colder episodes of the last glacial period30. Hence, peaks of this species can be reasonably correlated with cold climate events (i.e., Heinrich Events and Greenland Stadials). The term “Northern guests” is referred only to ostracod taxa currently living outside the Mediterranean Sea (at northern latitudes) and which arrive to the Mediterranean during “cold” Quaternary climatic episodes31. Following this criteria, here we consider as “Northern guests” such ostracod species that do not live today in the Bay of Biscay (having a circumpolar distribution, i.e., “cold-water” proxies) and which enter into the Basque shelf only during some cold climatic events, namely Acanthocythereis dunelmensis, Cytheropteron testudo and “Trachyleberis” sp.

Selected specimens of foraminifers and ostracods from the outer Basque shelf (Southern Bay of Biscay) used in this study.

(1) Benthic foraminifer species: Lobatula lobatula, spiral view. (2-3) Planktonic foraminifer species: (2) Globigerina bulloides, oral view; (3) Neogloboquadrina pachyderma left coiling (sin), oral view. (4–6) “Northern guest” ostracod species (all lateral external views): (4) Cytheropteron testudo, right valve; (5) Acanthocythereis dunelmensis, right valve; (6) “Trachyleberis” sp., left valve. Scale bar = 100 μm.

The stable oxygen isotope ratio (δ18O) is one of the most extensively used tools in palaeoclimatology and palaeoceanography. In marine sediments, the δ18O values of planktonic and benthic foraminifer shells are used as proxies to reconstruct variations in salinity, temperature and isotopic composition of shallow (planktonic) and deep (benthic) sea water, to analyze fluctuations in global ice volume, to identify changes in oceanic water masses and to construct a high resolution time scale during the Quaternary32,33. The δ18O ratio of many planktonic and benthic foraminifer species, such as Globigerina bulloides and Cibicides spp., has been considered to be in equilibrium with the δ18O signal of surface and bottom waters, or to have a constant offset, what allows to identify changes in water masses properties and establish a consistent stratigraphy of marine sedimentary cores of the North Atlantic Ocean34,35. Therefore, here we use the oxygen isotopic signal δ18O measured in Lobatula lobatula (benthic foraminifer) and G. bulloides (planktonic foraminifer) to detect changes on the characteristics of, respectively, bottom and surface water masses in the Basque shelf during the late Quaternary.

Antoliñako Koba (AK) (Gautegiz-Arteaga, Bizkaia, Spain: Fig. 1a) is an exceptional archaeo-palaeontological karstic deposit with a long Upper Pleistocene sequence, comprising nine chrono-cultural units: Aurignacian, evolved Aurignacian, Gravettian, Upper Solutrean, late Lower Magdalenian, Upper Magdalenian, Azilian and ancient Epipaleolithic36,37,38. There are also scarce pre-Aurignacian evidences of human presence in an underlying still undated layer36. The chronology of AK roughly goes from nearly 44 to 9 ka cal BP. Details of the stratigraphy, lithic industries, portable art and contextualization of the site in the regional prehistory are to be found elsewhere36,37,38,39,40. The good preservation of the materials from AK allowed us to obtain both the small-vertebrate collection and the red deer (Cervus elaphus) bone samples, the latter used for stable isotope analysis (see Methods). Pollen cores were also taken from the entire sequence. Unfortunately they revealed to be sterile in all cases (María José Iriarte, pers. comm.).

Many radiocarbon dates obtained for the AK’s sequence (see Table 1 and Fig. 4, 1st and 2nd columns), made it possible to correlate the land and marine records between them and then with sedimentological and palynological episodes of the Cantabrian Region41,42, with the variations of the eustatic sea level43,44 and with a δ18O curve from a deep ice-core of north Greenland (NGRIP45). Two main objectives are pursued in this study: 1) contrast the mainland and marine records of the same region, filling the gaps that commonly exist along the mainland sequences with the usually more complete marine record; and 2) obtain a continuous palaeoenvironmental reconstruction for the 44–9 ka cal BP period at the Cantabrian Region by correlating and cross-checking several proxies (small vertebrates, marine record and stable isotopes of herbivores), correlating those proxies in turn with well-known North-Atlantic records.

Multi-proxy estimated palaeoenvironmental reconstruction for the Cantabrian Region during the Upper Pleistocene.

From left to right, columns represent the 14C BP radiocarbon dates (with laboratory codes); the 14C BP 2σ calibrated (cal) radiocarbon dates using the IntCal13.14c data set66; the stratigraphic levels of AK; the cultural horizons defined by their archaeological contents; the stratigraphic sequence of AK; the location of the samples; the small-mammal taxa grouped by their habitat requirements; the amphibian and reptile taxa grouped by their habitat requirements; the δ13C and δ15N values of C. elaphus from AK; the relative abundances of N. pachyderma sin (planktonic foraminifer) and “Northern guest” species (benthic ostracods) over time; the δ18O signals of G. bulloides (planktonic foraminifer) and L. lobatula (benthic foraminifer) over time; the sedimentological41 and palynological42 episodes for the Cantabrian Region; the North-Atlantic sea-level curves43,44; and a δ18O curve obtained from a deep ice core of North Greenland (NGRIP45) displaying some well-known North-Atlantic climatic episodes (HE 1 phases52 and limits between MIS68 were taken from elsewhere). AK, Antoliñako Koba; ST., sterile layer; Prebor., Preboreal; MWP, melt water pulse; HCE, Holocene Cooling Event; YD, Younger Dryas; B/A, Bölling/Alleröd; GI, Greenland Interstadial; HE, Heinrich Event; LGM, Last Glacial Maximum; MIS, Marine Isotope Stages.

Results

Small vertebrates

The small-vertebrate assemblage from AK comprises 28 taxa: four soricids (Sorex cf. coronatus, S. minutus, Neomys sp. and Crocidura russula); one talpid (Talpa sp.); one sciurid (Marmota marmota); two glirids (Glis glis and Eliomys quercinus); two murids (Apodemus sylvaticus and A. flavicollis); seven cricetids (Arvicola amphibius, Chionomys nivalis, Pliomys lenki, Microtus (Terricola) lusitanicus, M. (Alexandromys) oeconomus, M. (Microtus) arvalis and M. (M.) agrestis); five amphibians (Alytes obstetricans, Bufo bufo, B. calamita, Rana gr. temporaria-iberica and Triturus sp.); and six reptiles (Anguis fragilis, Chalcides striatus, Coronella girondica, cf. Natrix, Vipera sp. and Lacertidae indet.).

Figure 4 reconstructs the AK habitat distribution based on changes in the small-mammal (7th column) and amphibian and reptile (8th column) communities over time, respectively. The frequencies of the different taxa (expressed in NISP and MNI) and their habitat affinities are given in supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The species were ordered by stratigraphic levels covering the Aurignacian to ancient Epipaleolithic periods (Sm-P to Lanc), plus some pre-Aurignacian layers without a specific chrono-cultural assignation (Sm to B-Am). There are certain hiatuses and erosive episodes along the sequence shown in Fig. 4.

First to be noticed is the pre-eminence of forests at the bottom of the sequence. During pre-Aurignacian times, woodlands were important in the vicinity of the cave according to both the amphibian and reptile (AR) record (Level Sm) and the small-mammal (SM) record (Level Lsm-P). For the first clearly defined archaeological level (Sm-P) and since slightly before, the SM record documents two peaks of forest, the highest of the sequence, with a moderate presence of open landscapes as well. There is a notorious peak of rocky habitats at the top of Sj/P. The level called lower Lmbk/Smk, assigned to the evolved Aurignacian, is characterized by an equilibrium between woodland and meadows according to the SM and by a peak of open landscapes according to the AR. There is no contradiction but alternation in this case, as shown in Fig. 4.

Some degree of contradiction between the SM and AR records is present in the Gravettian layers. While the SM show a nearly similar representation of forests and meadows, the AR exhibit two peaks of meadow and one of woodland, with more presence of water component than in the SM. This discrepancy may be a bias due to the lower NISP of AR respect to SM in these particular levels (compare upper Lmbk/Smbk + Lab/Sab in supplementary Tables 1 and 2). After the second hiatus of the sequence, during Upper Solutrean times and according to the SM, there are two peaks of forest at levels Lmc and Lmb, respectively and a significant increase of rocky habitats (in detriment of woodland and meadows) in Lmb, immediately before the second peak of forest. The AR record supports the two forest peaks of the SM, being them considerably higher in AR.

The late Lower Magdalenian (lower Lgc) shows a predominance of woodland over open landscapes, especially in the SM. This tendency continues after a long hiatus. During Azilian times (upper Lgc) there are peaks of meadows in detriment of water habitats both in the SM and AR. The forest component remains high, but more according to the SM. Finally, towards the Ancient Epipaleolithic (represented by Level Lanc), we observe a reduction of woodland and open territory in favor of waters at the SM column, but an increase of meadows in the AR, in detriment of both forest and water habitats. The rocky areas are moderately represented since the Azilian to the top of the sequence, but only at the AR column.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes

The results of the carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) isotope analysis for the C. elaphus bone samples of AK are displayed in columns 9th and 10th of Fig. 4, respectively. The variation in red deer collagen δ13C values along the sequence is due to consumption of different types of plants. Cervus elaphus is classified as an intermediate feeder, with a mixed diet between grazing and browsing46,47. Red deer δ13C values could be attributed to graminoid and shrubbery feeding, particular to semi-open grasslands18,19,20. The δ13C values of AK specimens show a decreasing trend from the Upper Solutrean to the Azilian (~23–12 ka cal BP), ranging from δ13C −20.3 to −21.0‰ (supplementary Table 3 and supplementary Fig. 1a). This variation suggests a progressive increase in forest cover16. From the Aurignacian to the Gravettian (~36–30 ka cal BP) an opposite trend is recorded, probably reflecting a decrease of woodlands along this period.

Regarding the nitrogen, we observe an increase in δ15N values from the Upper Solutrean to the Azilian, mean values varying between δ15N 2.8 and 4.4‰ (supplementary Table 3 and supplementary Fig. 1b). This increase could be the result of a progressive rise in temperature19,20,22,23 (see Introduction). From the Aurignacian to the Gravettian the trend is ambiguous. During the Gravettian (upper Lmbk/Smbk + Lab/Sab), δ15N values exhibit two sets of isolated values: one with high values (δ15N = 7–8‰) and other with lower values (δ15N < 5‰). The presence of these two sets in the red deer of AK could represent populations coming from different territories. If we interpret the higher values as belonging to non-local individuals and we assume the lower values as valid, then the resulting tendency to a decrease in temperatures would be in agreement with the trend inferred from the δ13C (compare supplementary Figs. 1a and 1b).

Marine record

The palaeoceanographic evolution of the Basque shelf during the late Quaternary, based on microfaunal (% of N. pachyderma sin and “Northern guest” ostracod species) and isotopic (δ18O on G. bulloides [bull] and L. lobatula [lob]) signals, is shown in columns 11th and 12th of Fig. 4, reflecting the influence of diverse water masses in this area.

During MIS 3, the high percentage of N. pachyderma sin, together with the positive values of δ18Obull, indicates the influence of cold polar surface waters in the Basque shelf. Regarding the benthic record, the isotopic signal (δ18Olob) marks the presence of cold bottom waters in the Basque shelf. However, the scarcity of “Northern guest” ostracod species shows the absence of inputs of subpolar bottom waters4. The HE 3 (~31.3 ka cal BP) is a remarkable period: the marine record reflects the arrival of both surface and bottom cold subpolar waters into the Basque shelf 4,28.

At 23.9 ka cal BP, Heinrich Event (HE) 2 is detected by an increase in the percentage of N. pachyderma sin synchronic to a peak of δ18Obull, reflecting the arrival of cold polar surface waters4,28. This event is followed by a decrease in the isotopic signal (~23.2 ka cal BP) that corresponds to the warm event GI-2. The decrease in abundance of N. pachyderma sin and δ18Obull values during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) compared to HE 2, suggests an increase in temperature, a decrease in salinity of surface sea water48, and/or homogenisation of the water column49. However, the benthic signal reflects an input of cold subpolar bottom waters into the Basque shelf at ~21.3 ka cal BP4. This cold water shift affected only bottom waters and retreated during the rest of the LGM.

At the end of LGM (~20.1 ka cal BP), a new peak of abundance of N. pachyderma sin shows the entrance of cold polar surface waters into the Basque shelf. This can be correlated with the retreat and melting of the European ice sheets and glaciers occurred at 20 ka cal BP50, which caused a sea-level rise at around 19 ka cal BP (19 ky-melt water pulse; 19 ky-MWP in Fig. 4). From ~18.6 to ~15 ka cal BP, the HE 1 is characterized by the variations in relative abundance of N. pachyderma sin, “Northern guests” and δ18Obull and δ18Olob signals, reflecting the input of both cold surface and bottom water masses into the Basque shelf, coming from the circumpolar area of the North Atlantic Ocean4,28. These trend can be correlated with the age previously proposed for HE 1 in the Bay of Biscay, i.e., ~18 ka cal BP51,52,53.

The erosional hiatuses observed first at the beginning of MIS 2 (27.7–23.9 ka cal BP) and then at the beginning of the second phase of HE 1 (HE 1b)52 (17.1–16.5 ka cal BP), seem to be related to the sea level rise starting at ~17 ka cal BP54 that characterized the last Deglaciation (14.7–11.5 ka cal BP, beginning of MIS 1)4,28. This sea-level rise shows its maximum rates from ~14.6 to ~13.8 ka cal BP, during the melt-water-pulse 1a event (mwp-1a in Fig. 4)54. After the end of the Younger Dryas (YD, 11.3 ka cal BP) it comes a period of higher sea-level rates, called mwp-1b54 (Fig. 4), being the sea-level approximately −60 m respect to the current level. On the continental shelf of the Armorican margin (French margin, northern part of Capbreton Canyon), similar erosive processes were observed during the last Deglaciation, due to the same phenomenon55. In the Basque shelf, this rise, which occurred during the beginning of MIS 1 (last Deglaciation and early Holocene), is accompanied by a warming tendency on both surface and bottom waters, as shown by the marine proxies. The increase in abundance of “Northern guests”4,28 and δ18Olob signal at ~9.4 ka cal BP implies the input of cold subpolar bottom waters that may correspond to the Holocene Cooling Event (HCE) 656.

Discussion

Many proxies have been previously used to reconstruct past environments (e.g., Greenland ice-cores, tree-rings, pollen, tephrochronology, speleothems and marine record) and some comprehensive holistic efforts have been recently accomplished1, but none of them have directly compared small vertebrates, marine record and stable isotopes of red deer to yield a more complete and accurate panorama.

Our study shows how useful it can be to compare the land and marine records, particularly when the samples come from geographically close locations (Fig. 1), what prevents incompatibilities in the sequences. The environmental curves obtained from foraminifers and ostracods of the Southern Bay of Biscay are contemporaneous and complementary to those constructed with the small vertebrates (mammals, amphibians and reptiles) from AK. Some erosive episodes and/or sterile layers along the mainland sequence, provoking gaps in the record, can be successfully fulfilled by the marine record (relative abundances and isotopic signals of certain taxa), as it is the case for the periods ~41.2–37.4 ka cal BP, ~33.6–32 ka cal BP, ~18.2–20.5 ka cal BP and ~17.6–14.4 ka cal BP. In spite that the marine record is usually more complete than the mainland one4,28, the long erosive hiatus in the marine cores of the Basque shelf between 27.7 and 23.9 ka cal BP is partially covered by the small-vertebrate sequence.

The different records presented in Fig. 4 can be treated altogether or independently. If taken separately, the small-vertebrate record can be contrasted to other palaeoenvironmental reconstructions performed for the same region, as those of Santimamiñe3 (very close to AK), Askondo11, El Mirón6, El Conde10 and Valdavara-19. The mainland stable-isotope evidence can be compared with the recent contributions made for Kiputz IX2 and El Mirón57; and, finally, the reconstructions done departing from oceanic data (% of species and stable isotopes of foraminifers) can be contrasted to some others obtained for the southern Bay of Biscay51,53.

If used altogether, it is interesting to have a deeper look into the periods of the sequence where it is possible to contrast the results of the three different records (small vertebrates, marine and stable isotopes) for the Cantabrian Region and to compare them in turn with some other well-known North-Atlantic records (sedimentological, pollen, eustatic sea-level and NGRIP) to get a wider and more complex view. During the evolved Aurignacian period (~35–33.6 ka cal BP), for instance, small vertebrates show a combined (i.e., mammals plus amphibians and reptiles) scenario of a certain equilibrium between woodland and meadows, which coincides with the intermediate values of the δ13C and δ15N (supplementary Table 3 and supplementary Fig. 1), meaning moderately forested landscapes and mild temperatures, respectively. The percentages of N. pachyderma sin and the slightly positive tendency of δ18Obull values indicate moderate influence of polar surface waters in the Basque shelf, its effects in the general environment being thereafter also moderate.

The HE 3 (~31.3–29.8 ka cal BP) in the Basque shelf is clearly shown by the increase of N. pachyderma sin, “Northern guests” and the values of δ18Obull and δ18Olob, which indicate the arrival of both surface and bottom subpolar waters and its consequent influence in the general climate. This corresponds to a trend of deforestation in mainland, as shown by the higher values of δ13C respect to the Aurignacian and a decrease in temperatures if we consider the lower values of δ15N as valid (see Results). The combined panorama reflected by the small vertebrates coincides with the δ13C values in showing a more open scenario, especially notorious in the amphibian and reptile record. The partial coincidence with the Kesselt pollen phase should not be considered, as the chronology of this warm episode (likely more related to GI-5) and others has been brought into question42. At 23.2 ka cal BP there was a remarkable decrease of the G. bulloides isotopic signal. At the same time, a woodland peak is detected in the small-mammal record, which roughly coincides with the GI-2 warm event. The peak of rocky habitats at 21.3 ka cal BP, during the LGM, could be related to the high values of δ13C (deforestation) and the low values of δ15N (fall in temperature). In the oceanic front, high ratios of the planktonic and benthic isotopic signals reflect inputs of cold superficial and bottom waters. There is a peak of “Northern guests” at the same time. In sedimentological and palynological terms, the rocky-habitat peak coincides with the transition between the Cantabrian phases I (Oldest Dryas) and II (Lascaux)41, being the former especially cold and humid.

During the occupation of AK by Lower Magdalenian people, a trend of progressive forestation of landscapes can be inferred from both the small-vertebrate record and the δ13C values, the δ15N ratio showing a parallel, not surprising, rise in temperature respect to previous Solutrean times. The arrival of both bottom and surface cold water masses to the Basque shelf continues over this period, but there is a drop in quantities of N. pachyderma sin and negative trends of δ18Obull and δ18Olob at the uppermost part. These curves nicely fit with phase V of the Cantabrian Region41, in the sedimentological front. The Azilian chrono-cultural period roughly coincides with the YD. This is a time of peaks of woodland in the small-vertebrate record, which correspond to forestation after the δ13C signal and to ascending temperatures after δ15N values. Numbers of N. pachyderma sin and δ18Obull values diminish accordingly. The benthic signal, however, shows inputs of subpolar bottom waters towards the half of this period. The palynological (Dryas III) and sedimentological (Phase IX) data reflects mild conditions41. This trend of progressive increase in woodland and rise in temperatures from Magdalenian times up to the Holocene is clearly recorded also in the sequences of Santimamiñe3, El Mirón6 and Kiputz IX2.

Along HE 3 and HE 2, contrary to the rest of the proxies, the small mammals do not display particularly open landscapes. At the top of the Upper Solutrean, there are peaks of forest according to the small-vertebrate evidence (especially amphibians and reptiles) during the LGM, while the stable isotopes of red deer and the marine signals suggest priority of meadows and low temperatures. Finally, towards Epipaleolithic times, there is a retreat of woodlands after the small vertebrates, what is not coherent with what is inferred from the marine record. It should be stated then that together with coincidences, our sequence displays also some discrepancies: either some proxies do not reflect specific events with the same intensity as others, or they show opposite trends in few cases. These inconsistencies represent a challenge for future studies.

Methods

Small-vertebrate materials

The assemblage includes nearly 31400 elements, of which 2470 were identified either to the family, genus and/or species level. To obtain the samples, the sediment from the different stratigraphic levels of the cave was water-screened using a stack of sieves of decreasing mesh size (4 and 0.5 mm). The small vertebrates were collected from residue coarser than 0.5 mm. Fossils were sorted, classified, counted and studied with the aid of a binocular microscope (Nikon SMZ-U; 7x, 20x and 40x magnifications). Most of the elements are teeth, isolated mandibles, skull fragments and postcranial bones.

Systematic attribution and quantification

Each small-vertebrate taxon was identified based on cranial and post-cranial diagnostic elements: isolated teeth for the Murinae and Gliridae; first lower molars for the Arvicolinae; mandibles, maxillae, isolated teeth and post-cranial skeleton for the Talpidae and Soricidae; humerus, ilium, scapula and sacrum for amphibians; skull elements, vertebrae and osteoderms for lizards and trunk vertebrae for snakes. The taxonomic classification follows well-known references58,59. In spite that in Fig. 2 we show two discernible second upper molars of Apodemus sylvaticus and A. flavicollis (Fig. 2(2, respectively), most elements of the sample exhibit ambiguous morphologies. The relative ratios of fossil species were established with the minimum number of individuals (MNI), also used as a quantitative measure to reconstruct the palaeoenvironment. To determine the MNI, a diagnostic tooth (e.g., first lower molar in arvicolines) or post-cranial elements were considered, taking into account laterality and sex whenever possible.

Taphonomic remarks

The light to moderate gastric digestion and scant breakage observed in the small-vertebrate remains, indicates that the bones were likely accumulated by an avian predator of category 15 such as a barn owl (Tyto alba), which is an opportunistic rather than a selective hunter. However, there are certain instances of great to extreme modification, which means categories IV to V on Andrews' scale5. In these cases, the agents of deposition were most probably small-mammalian carnivores. The pattern of skeletal-element frequency for the slow worm, with lack of digestion traces, would correspond to in situ mortality. Therefore, there are no signs of alteration suggesting that the Antoliña assemblage is not representative of the ecosystem in the immediate vicinity of the cave at the time when the remains were deposited.

Habitat weightings

We distribute each small-vertebrate taxon in the habitat(s) where it is possible to find them at present, especially in the Cantabrian Region8,60,61. Habitats were divided into four types3,6,7,9,10,11, which are detailed as follows (see supplementary Tables 1 and 2): Forest: mature woodland, including woodland margins and forest patches, with moderate ground cover; Meadow: evergreen open areas with dense pastures and suitable topsoil; Water: streams, lakes, ponds and marshes; Rocky: areas with suitable rocky or stony substratum. The Meadow type, as defined here, is particularly suitable for the well-known humid conditions of the Cantabrian Range60,61. For the rest of Mediterranean Iberia, a Grassland or Open-dry category is required.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis

A total of 38 samples from AK specimens were analyzed, ten of which were not considered for interpretations due to low concentrations of collagen (supplementary Table 3). Only 28 samples had C/N atomic ratios between 2.9 and 3.6, which indicates good collagen preservation62. The stratigraphic distribution of the useful samples is as follows: evolved Aurignacian (5), Gravettian (12), Upper Solutrean (3), Lower Magdalenian (6) and Azilian (5). Bone collagen (coll) from red deer (C. elaphus) long bones was extracted following a specific procedure63. Three-hundred mg of bone sample powder was demineralized in 1 M HCl for 20 min at ambient temperature until all minerals had dissolved. Samples were then rinsed with distilled water and 0.125 M NaOH was added to remove humic acid. They were then rinsed with distilled water again and gelatinized in a pH 3 HCl solution for 17 h at 90 °C. The filtered supernatant containing the soluble collagen was then collected, frozen and lyophilized. Collagen (2.5–3.5 mg) was loaded into a tin capsule for continuous flow combustion and isotopic analysis. Isotope analyses were performed for carbon and nitrogen isotopes using a continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-IRMS) at Iso-Analytical (Cheshire, UK). The bone collagen amount is 12.8–0.36 %wt. The Ccoll and Ncoll contents are above 25.6% and 8.2% wt respectively and the C/N atomic ratio is 3.2–3.6, which corresponds to well-preserved collagen63. Multiple samples of the liver standard NBS-1577B and ammonium sulphate IA-R045 working standard were run to confirm instrument accuracy. Replicate analysis of the NBS-1577B δ13C standard during runs gave a 13C/12C of –21.65 ± 0.07 (s, n = 12); NBS-1577B δ15N standard during runs gave a 15N/14N of 7.63 ± 0.14 (s, n = 12) and the IA-R045 working standard during runs gave a 15N/14N of −4.70 ± 0.05 (s, n = 5).

Stable oxygen isotope analysis

Values of δ18O were measured on the shells of the planktonic foraminifer species Globigerina bulloides and of the benthic foraminifer species Lobatula lobatula (supplementary Table 4). Between 2 and 18 specimens per sample were handpicked for each species. These individuals were washed in alcohol and placed in an ultrasonic cleaner for less than 10 seconds in order to eliminate any contaminating residual adhering to the foraminifer test. δ18O data obtained are reported referred to the PeeDee belemnite (V-PDB) standard. Analyses were accomplished in the Leibniz Laboratory for Radiometric Dating and Stable Isotope Research (Kiel University, Germany) using a “Finnigan DELTAplusXL” mass-spectrometer coupled to a “GasBench II” continuous flow interface, equipped with a “CTC Combi PAL Autosampler”. The analytical error of analysis was lower than ±0.1‰.

Marine record

It is based on a composite stack of the faunistic (foraminifers and ostracods) and isotopic (δ18O) analysis of two cores from the outer Basque shelf (Southern Bay of Biscay): KS04-16 (43°32'66 N latitude, 2°05'72 W longitude, 294 m water depth), taken at the eastern flank of the San Sebastian Canyon and KS05-05 (43°30'597 N latitude, 2°13'76 W longitude, 259 mwd.), obtained at the western flank (see Fig. 1b for location and supplementary Table 4 for raw data).

The stratigraphic framework of both cores has been proposed elsewhere4,28. It is based on a combination of calibrated AMS 14C dates and an independent local event-stratigraphy constructed tuning the percentage of N. pachyderma left coiling (sin) to the NGRIP ice core δ18O record from Greenland (with the GICC05 time-scale)45 and to the MD95-2042 marine sedimentary core δ18O record from the SW Iberian Peninsula shelf35. The section studied here covers ~35 ka (from 43.1 ka cal BP to 7.9 ka cal BP), with the loss of 3.8 ka during the beginning of MIS 2 (27.7–23.9 ka cal BP) and of 0.6 ka during HE 1 (17.1–16.5 ka cal BP) due to two erosive hiatuses. Sedimentation rates range between 2 and 10 cm/ka resulting in a time resolution of approximately 1400 years for MIS 3 interval, ~620 years for MIS 2 and ~2200 years for the beginning of MIS 1.

In order to study the benthic and planktonic faunas, 11 samples (continuous intervals of 5 cm) were analyzed from core KS05-05 and 18 samples (intervals between 2 cm and 13 cm) from core KS04-16. Samples were water-screened with a 150 μm mesh sieve. All the ostracods present in the samples and at least 300 individuals of planktonic foraminifers per sample were picked4. Several taxonomical references have been used to identify the ostracod and foraminifer species49,64,65. To identify the input of cold circumpolar surface and bottom water masses into the Basque shelf, only the percentage of polar planktonic foraminifer species N. pachyderma sin and the accumulative percentage of “Northern guest” ostracod species, have been considered in this work.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Rofes, J. et al. Combining Small-Vertebrate, Marine and Stable-Isotope Data to Reconstruct Past Environments Sci. Rep. 5, 14219; doi: 10.1038/srep14219 (2015).

References

Rasmussen, S. O., Brauer, A., Moreno, A. & Roche, D. (eds). Dating, synthesis and interpretation of palaeoclimatic records and model-data integration: Advances of the INTIMATE (INTegration of Ice core, MArine and TErrestrial records) COST Action ES0907. Quat. Sci. Rev. 106, 1–330 (2014).

Castaños, J. et al. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes of bone collagen of large herbivores from the Late Pleistocene Kiputz IX cave site (Gipuzkoa, north Iberian Peninsula) for palaeoenvironmental reconstruction. Quat. Int. 339-340, 131–138 (2014).

Rofes, J. et al. The long paleoenvironmental sequence of Santimamiñe (Bizkaia, Spain): 20,000 years of small mammal record from the latest Late Pleistocene to the middle Holocene. Quat. Int. 339-340, 62–75 (2014).

Martínez-García, B., Rodríguez-Lázaro, J., Pascual, A. & Mendicoa, J. The “Northern guests” and other palaeoclimatic ostracod proxies in the late Quaternary of the Basque Basin (S Bay of Biscay). Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 419, 100–114 (2015).

Andrews, P. Owls, Caves and Fossils (The Natural History Museum Publications, London, 1990).

Cuenca-Bescós, G., Straus, L. G., González-Morales, M. R. & García-Pimienta, J. C. The reconstruction of past environments through small mammals: from the Mousterian to the Bronze Age in El Mirón Cave (Cantabria, Spain). J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 947–955 (2009).

Rofes, J. et al. Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the early Neolithic to middle Bronze Age Peña Larga rock shelter (Álava, Spain) from the small mammal record. Quat. Res. 79, 158–167 (2013).

Pokines, J. T. The Paleoecology of Lower Magdalenian Cantabrian Spain (British Archaeological Reports International Series 713, London, 1998).

López-García, J. M. et al. Small-vertebrates (Amphibia, Squamata, Mammalia) from the late Pleistocene-Holocene of the Valdavara-1 cave (Galicia, northwestern Spain). Geobios 44, 253–269 (2011a).

López-García, J. M. et al. Palaeoenvironment and palaeoclimate of the Mousterian-Aurignacian transition in northern Iberia: The small-vertebrate assemblage from Cueva del Conde (Santo Adriano, Asturias). J. Hum. Evol. 61, 108–116 (2011b).

Garcia-Ibaibarriaga, N. et al. A palaeoenvironmental estimate in Askondo (Bizkaia, Spain) using small-vertebrates. Quat. Int. 364, 244–254 (2015).

Gröcke, D. R., Bocherens, H. & Mariotti, A. Annual rainfall and nitrogen-isotope correlation in macropod collagen: applications as a palaeoprecipitation indicator. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 153, 279–285 (1997).

Hedges, R. E. M., Stevens, R. E. & Richards, M. P. Bone as a stable isotope archive for local climatic information. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 959–965 (2004).

Gannes, L. Z., Martinez del Río, C. & Koch, P. Natural abundance variations in stable isotopes and their potential uses in animal physiological ecology. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 119A, 725–737 (1998).

Winter, K. & Holtum, J. A. M. The effects of salinity, crassulacean acid metabolism and plant age on the carbon isotope composition of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L., a halophytic C3-CAM species. Planta 222, 201–209 (2005).

Tieszen, L. L. Natural variations in the carbon isotope values of plants: implications for archaeology, ecology and palaeoecology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 18, 227–248 (1991).

Heaton, T. H. E. Spatial, species and temporal variations in the 13C/12C ratios of C3 plants: implications for palaeodiet studies. J. Archaeol. Sci. 26, 637–649 (1999).

Iacumin, P., Nikolaev, V. & Ramigni, M. C. and N stable isotope measurements on Eurasian fossil mammals, 40000 to 10000 years BP: herbivore physiologies and palaeoenvironmental reconstruction. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 163, 33–47 (2000).

Drucker, D. G., Bocherens, H. & Billiou, D. Evidence for shifting environmental conditions in Southwestern France from 33000 to 15000 years ago derived from carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 natural abundances in collagen of large herbivores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 216, 163–173 (2003a).

Drucker, D. G., Bocherens, H., Bridault, A. & Billiou, D. Carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition of red deer (Cervus elaphus) collagen as a tool for tracking palaeoenvironmental change during the Late-Glacial and Early Holocene in the northern Jura (France). Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 195, 375–388 (2003b).

Stevens, R. E. et al. Nitrogen isotope analyses of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), 45,000 BP to 9,000 BP: Palaeoenvironmental reconstructions. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 262, 32–45 (2008).

Stevens, R. E. & Hedges, R. E. M. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of Northwest European horse bone and tooth collagen, 40000 BP-present: palaeoclimatic interpretations. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 977–991 (2004).

Drucker, D. G., Bridault, A. & Cupillard, C. Environmental context of the Magdalenian settlement in the Jura Mountains using stable isotope tracking (13C, 15N, 34S) of bone collagen from reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Quat. Int. 272-273, 322–332 (2012).

Iacumin, P., Bocherens, H., Delgado Huertas, A., Mariotti, A. & Longinelli, A. A stable isotope study of fossil mammal remains from the Paglicci cave, Southern Italy. N and C as paleoenvironmental indicators. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 148, 349–357 (1997).

Cronin, T. M. & Raymo, M. E. Orbital forcing of deep-sea benthic species diversity. Nature 385, 624–627 (1997).

Kandiano, E. S. & Bauch, H. A. Surface ocean temperatures in the north-east Atlantic during the last 500 000 years: evidence from foraminiferal census data. Terra Nova 15, 265–271 (2003).

Alvarez Zarikian, C. A., Stepanova, A. Y. & Grützner, J. Glacial-interglacial variability in deep sea ostracod assemblage composition at IODP Site U1314 in the subpolar North Atlantic. Mar. Geol. 258, 69–87

Martínez-García, B., Bodego, A., Mendicoa, J., Pascual, A. & Rodríguez-Lázaro, J. Late Quaternary (Marine Isotope Stage 3 to Recent) sedimentary evolution of the Basque shelf (southern Bay of Biscay). Boreas 43, 973–988 (2014).

Bé, A. W. H. In Oceanic Micropaleontology (ed Ramsay, A. T. S. ) 1–100 (Academic Press, New York, 1977).

Eynaud, F. et al. Position of the Polar Front along the western Iberian margin during key cold episodes of the last 45 ka. Geochem., Geophys., Geosyst. 10, Q07U05, 10.1029/2009GC002398 (2009).

Ruggieri, G. Nuovi ostracodi nordici nel Pleistocene della Sicilia. Boll. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 16, 81–85 (1977).

Duplessy, J.-C. et al. Surface salinity reconstruction of the North Atlantic Ocean during the last glacial maximum. Oceanology Acta 14 (4), 311–324 (1991).

Rohling, E. J. & Cooke, S. In Modern Foraminifera (ed. Sen Gupta, B. K. ) 239–258 (Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, 1999).

Bard, E. et al. Sea level estimates during the last deglaciation based on δ18O and accelerator mass spectrometry 14C ages measured on Globigerina bulloides. Quat. Res. 31, 381–391 (1989).

Shackleton, N. J. δ13C, δ18O (Globigerina bulloides) of sediment core MD95-2042. PANGAEA, 10.1594/PANGAEA.58195 (2001).

Aguirre, M. El yacimiento paleolítico de Antoliñako Koba (Gautegiz-Arteaga, Bizkaia): secuencia estratigráfica y dinámica industrial. Avance de las campañas de excavación 1995-2000. Illunzar 98/00 4, 39–81 (2001).

Aguirre, M., López Quintana, J. C. & Sáenz De Buruaga, A. Medio ambiente, industrias y poblamiento prehistórico en Urdaibai (Gernika, Bizkaia) del Würm reciente al Holoceno medio. Illunzar 98/00 4, 13–38 (2001).

Aguirre, M. & González, C. Canto con grabado figurativo del Gravetiense de Antoliñako Koba (Gautegiz-Arteaga, Bizkaia). Implicaciones en la caracterización de las primeras etapas de la actividad gráfica en la región Cantábrica. Kobie 30, 43–61 (2011).

Aguirre, M. (2013) In Pensando el Gravetiense: nuevos datos para la Región Cantábrica en su contexto (eds De las Heras, C., Lasheras, J. A., Arrizabalaga, A. & De la Rasilla, M. ), 216–228. Monografías del Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, 23 (Ministerio de Cultura, Santander, 2013).

Tarriño, A., Yusta, I. & Aguirre, M. Indicios de circulación a larga distancia de sílex en el Pleistoceno superior. Datos petrográficos y geoquímicos de materiales arqueológicos de Antoliñako Koba. Bol. Soc. Esp. Mineralog. 21-A, 200–201 (1998).

Hoyos, M. In El final del Paleolítico Cantábrico. Transformaciones ambientales y culturales durante el Tardiglacial y comienzos del Holoceno en la Región Cantábrica (eds Moure, A. & González, C. ) 15–75 (Universidad de Cantabria, Santander, 1995).

Sánchez-Goñi, M. F. & d’Errico, F. In Neandertales Cantábricos. Estado de la cuestión (eds Montes, R. & Lasheras, J. A. ) 115–129. Monografías del Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, 20 (Ministerio de Cultura, Santander, 2005).

Waelbroeck, C. et al. Sea-level and deep water temperature changes derived from benthonic foraminifera isotopic records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 295–305 (2002).

Siddall, M. et al. Changing influence of Antarctic and Greenland temperature records on sea level over the last glacial cycle. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 410–423 (2010).

Svensson, A. A 60,000 year Greenland stratigraphic ice core chronology. Clim. Past 4, 47–57 (2008).

Gebert, C. & Verheyden-Tixier, H. 2001. Variations of diet composition of Red Deer. (Cervus elaphus L.) in Europe. Mammal Rev. 31, 189–201 (2001).

Hulbert, I. A. R., Iason, G. R. & Mayes, R. W. The flexibility of an intermediate feeder: dietary selection by mountain hares measured using faecal n-alkanes. Oecologia 129, 197–205 (2001).

Volkmann, R. & Mensch, M. Stable isotope composition (δ18O, δ13C) of living planktic foraminifers in the outer Laptev Sea and the Fram Strait. Mar. Micropaleontol. 42, 163–188 (2001).

Hemleben, C., Spindler, M. & Anderson, O. R. Modern Planktonic Foraminifera (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1989).

Clark, P. U., McCabe, A. M., Mix, A. C. & Weaver, A. J. Rapid sea level rise at 19,000 years ago and its global implications. Science 304, 1141–1144 (2004).

Zaragosi, S. et al. Initiation of the European deglaciation as recorded in the northwestern Bay of Biscay slope environments (Meriadzek Terrace and Trevelyan Escarpment): a multi-proxy approach. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 188, 493–507 (2001).

Penaud, A. et al. What forced the collapse of European ice sheets during the last two glacial periods (150 ka B.P. and 18 ka cal B.P.)? Palynological evidence. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 281, 66–78 (2009).

Eynaud, F. et al. New constraints on European glacial freshwater releases to the North Atlantic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L15601, 10.1029/2012GL052100 (2012).

Stanford, J. D. et al. Sea-level probability for the last deglaciation: A statistical analysis of far-field records. Glob. Planet. Change 79, 193–203 (2011).

Toucanne, S. et al. External controls on turbidite sedimentation on the glacially-influenced Armorican margin (Bay of Biscay, western European margin). Mar. Geol. 303, 137–153 (2012).

Bond, G. C. et al. A pervasive millennial-scale cycle in North Atlantic Holocene and Glacial climates. Science 278, 1257–1266 (1997).

Stevens, R. E., Hermoso-Buxán, L., Marín-Arroyo, A. B., González-Morales, M. R. & Strauss, L. G. Investigation of Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene palaeoenvironmental change at El Mirón cave (Cantabria, Spain): Insights from carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses of red deer. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 414, 46–60 (2014).

Wilson, D. E. & Reeder, D. M. (eds). Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2005).

Carretero, M. A., Martínez-Solano, I., Ayllón, E. & Llorente, G. Lista patrón de los anfibios y reptiles de España (Actualizada a diciembre de 2014). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272447364_Lista_patrn_de_los_anfibios_y_reptiles_de_Espaa_(Actualizada_a_diciembre_de_2014). Downloaded on 2 March 2015.

Álvarez, J., Bea, A., Faus, J. M., Castién, E. & Mendiola, I. 1985. Atlas de los Vertebrados Continentales de Álava, Vizcaya y Guipúzcoa (Gobierno Vasco, Vitoria-Gasteiz, 1985).

Palomo, J. L. & Gisbert, J. (eds). Atlas de los mamíferos terrestres de España (Dirección General para la Biodiversidad, Madrid, 2005).

DeNiro, M. J. Postmortem preservation and alteration of in vivo bone collagen isotope ratios in relation to palaeodietary reconstruction. Nature 317, 806–809 (1985).

Bocherens, H. et al. Isotopic biogeochemistry (13C, 15N) of fossil vertebrate collagen: application to the study of a past food web including Neanderthal man. J. Hum. Evol. 20, 481–492 (1991).

Loeblich, A. R. & Tappan, H. Foraminiferal genera and their classification (Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 1988).

Athersuch, J., Horne, D. J. & Whittaker, J. E. In Synopses of the British Fauna. New Series, 43 (Linnean Society of London and Estuarine and Coastal Sciences Association, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1989).

Reimer et al. IntCal13 and MARINE13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0-50000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 55 (4), 10.2458/azu-js-rc.55.16947 (2013).

Stuvier, M., Reimer, P. J. & Reimer, R. W. CALIB 7.0.4. http://calib.qub.ac.uk/calib/ (2015). Downloaded on 27 February 2015.

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography 20, PA1003, 10.1029/2004PA001071 (2005).

Acknowledgements

J. Rofes has a postdoc Marie Curie Fellowship (MCA-IEF Project nº629604) of the European Comission; he is also a member of the Atapuerca Project CGL2012-38434-C03-01 of the “Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de España” (MINECO). B. Martínez-García has a postdoc Grant (“Contratación para la especialización de personal investigador doctor”) of the UPV-EHU. N. Garcia-Ibaibarriaga has a pre-doctoral Fellowship (BFI-2010-289) of the Basque Government. We received economical support from the Project GIU12/35 of the UPV-EHU. The “Diputación Foral de Bizkaia” financed all the fieldwork campaigns at AK. Thanks to Mónica Aguilera and Carlos Tornero for their thoughtful comments on stable isotope topics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study idea and coordination by J.R. J.R., N.G.I., M.A., B.M.G., L.O., M.C.Z. and X.M. designed the research. All authors analyzed the data, interpreted the results and wrote the paper. Specific research fields by author: J.R. and X.M. (small mammals); N.G.I. and S.B. (amphibians and reptiles); L.O., M.C.Z., A.A.O. and J.C. (stable-isotope analysis and large mammals); B.M.G. (marine record); M.A. (archaeology of AK site).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rofes, J., Garcia-Ibaibarriaga, N., Aguirre, M. et al. Combining Small-Vertebrate, Marine and Stable-Isotope Data to Reconstruct Past Environments. Sci Rep 5, 14219 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14219

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14219

This article is cited by

-

Adaptability, resilience and environmental buffering in European Refugia during the Late Pleistocene: Insights from La Riera Cave (Asturias, Cantabria, Spain)

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Changing environments during the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic transition in the eastern Cantabrian Region (Spain): direct evidence from stable isotope studies on ungulate bones

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Radiocarbon dating minute amounts of bone (3–60 mg) with ECHoMICADAS

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Variations in Microtus arvalis and Microtus agrestis (Arvicolinae, Rodentia) Dental Morphologies in an Archaeological Context: the Case of Teixoneres Cave (Late Pleistocene, North-Eastern Iberia)

Journal of Mammalian Evolution (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.