Abstract

We report on quantitative comparison between the electric dipole energy and the Rashba band splitting in model systems of Bi and Sb triangular monolayers under a perpendicular electric field. We used both first-principles and tight binding calculations on p-orbitals with spin-orbit coupling. First-principles calculation shows Rashba band splitting in both systems. It also shows asymmetric charge distributions in the Rashba split bands which are induced by the orbital angular momentum. We calculated the electric dipole energies from coupling of the asymmetric charge distribution and external electric field and compared it to the Rashba splitting. Remarkably, the total split energy is found to come mostly from the difference in the electric dipole energy for both Bi and Sb systems. A perturbative approach for long wave length limit starting from tight binding calculation also supports that the Rashba band splitting originates mostly from the electric dipole energy difference in the strong atomic spin-orbit coupling regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rashba band splitting in a system with an inversion symmetry breaking (ISB) such as material surfaces and hetero-structures recently has drawn much attention in condensed matter physics community1,2,3,4,5. In addition to its fundamental importance, it is believed that it plays a vital role in spin-orbit torque in spintronic materials3. It is thus important to thoroughly understand the origin of the Rashba band splitting. Tight binding and first-principles calculations reproduce very well the experimentally observed Rashba band splittings on material surfaces6,7,8. Especially, tight binding calculations show that atomic spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is a crucial parameter in the Rashba band splitting6. However, it had been unclear which interaction among many is crucial for the Rashba band splitting.

It was recently found that the atomic orbital angular momentum (OAM) exists in the presence of the ISB and that it induces an asymmetric charge distribution for non-zero crystal momentum9. The dipole energy from the interaction between asymmetric charge distribution and the electric field from the ISB is proposed to be responsible for the Rashba band splitting in the strong SOC case. The proposed effective Hamiltonian for the Rashba band splitting is H = αL · S − αk(k × L) · Es, where α, L, S, αK, k and Es are SOC parameter, OAM, spin angular momentum (SAM), coupling parameter for electric dipole interaction, crystal momentum and electric field induced by the ISB, respectively10,11. The first term in the Hamiltonian is the usual atomic SOC while the second term represents the newly proposed electric dipole energy. It has been previously conjectured that the atomic SOC determines the Rashba band splitting in weak atomic SOC regime while the new dipole energy term does so in strong atomic SOC regime11,12. In both cases, the existence of the OAM is essential.

The existence of the OAM in Rashba bands was shown by tight binding and first-principles calculations9,13. It was also experimentally supported in the observation of strong circular dichroism in angle-resolved photoemission (ARPES)10,11,14,15. While the existence of the OAM is certain, its role in the Rashba band splitting does not appear to be fully accepted. Part of the reason could be from the fact that quantitative estimation of the OAM contribution based on, for example, first-principles calculation has not been performed. Therefore, a quantitative comparison between the electric dipole energy difference and the Rashba band splitting in neighboring bands is desired, especially in the strong atomic SOC case. Significance in the electric dipole energy difference compared to the total Rashba band splitting energy should prove the validity of the OAM based effective Rashba model.

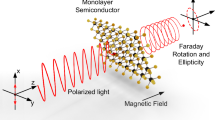

To show the importance of the electric dipole energy in a quantitative way, we performed first-principles and tight binding calculations on Bi and Sb monolayers with an external field. Use of monolayers with an external field is to mimic the surface state without dealing with complicated bulk states. This is a simple enough model for the purpose of our research to explore the origin of the Rashba band splitting of the surface states. Both first-principles and tight binding calculations are complementary to each other. The electric dipole energy is estimated by using the wave functions from first-principles calculation, which is not model-dependent, while tight binding calculations allow us to have more intuitive analysis on the band structures and wave functions. The outcome from the interaction between the asymmetric charge distribution and the electric field is responsible for the Rashba band splitting in Bi and Sb monolayers.

Results and Discussions

First-principle calculations

We present in Fig. 1 the band structures of Bi and Sb single layers under an electric field 0.5 V/Å along the direction perpendicular to the layers. The six bands are composed of p-orbitals of Bi or Sb atoms. Bands 1 and 2 are mainly of J ≈ 1/2 character while bands 3 to 6 come from mainly J ≈ 3/2 states. We can see the Rashba splitting in the band structure near the Γ and M points which are time reversal invariant momenta (TRIM) of the triangular lattice. Bi single layer whose atomic SOC is stronger than that of Sb shows a larger Rashba splitting in its band structure, which indicates that the magnitude of the Rashba splitting is clearly related to the atomic SOC strength. Indeed, the Rashba splitting observed at Cu, Ag and Au surfaces also show such correlation between the atomic SOC and the size of the Rashba splitting16.

In Fig. 2, we plot the expectation values of in-plane components of SAM and OAM of the Bi single layer near the Γ point. The SAM and OAM for Sb single layer (not shown here) have the same trends as those of Bi single layer. The only difference is the smaller OAM magnitude for Sb compared with Bi, which might be the result of the small SOC in Sb. All the OAM patterns of the bands show chiral structures around the Γ point and the chiral directions of adjacent bands are opposite to each other. SAM also has similar patterns to those of OAM because of the strong SOC. SAM for J ≈ 1/2 bands (bands 1 and 2) are antiparallel to OAM while they are almost parallel to the OAM directions in J ≈ 3/2 bands (bands 3 to 6).

SAM and OAM of Bi triangular lattice under the field.

SAM and OAM of bands 1 to 6 of Bi triangular lattice near the Γ point are shown in (b). The numbers indicate the band indices shown in Fig. 1. Red arrows are SAM and blue arrows are OAM. The  space region for (b) is shown in (a) as dotted square.

space region for (b) is shown in (a) as dotted square.

We notice that while the OAM magnitude is the largest in the bands 1 and 2, the largest band splitting exists in bands 3 and 4. Therefore, the magnitude of OAM cannot be directly linked to the size of the Rashba band splitting. Instead, asymmetric charge distribution, which results from interference of adjacent atomic orbitals with OAM, is found to be proportional to the size of the Rashba band splitting. Therefore, the overlap between adjacent atomic orbitals is also an important factor in the determination of the asymmetric charge distribution, hence the Rashba band splitting. We believe that the electric dipole moments of the states in bands 3 and 4 become stronger than those in bands 1 and 2 due to larger overlap between adjacent atomic orbitals. We will discuss this issue in more detail below.

We plot the charge densities around a Bi atom for crystal momenta k = 0.2π/a and 0.4π/a along the Γ-M direction in Fig. 3. Bands 3 and 4 show clear charge asymmetry along the z-direction. Other bands show rather small asymmetry. So, it can be noticed that the magnitude of band splitting is closely related to the electric dipole moment of a state in the band. Bands 1 and 2 have a shape of pz orbital and therefore small orbital overlap between nearest atoms, resulting in small charge asymmetry, which reveals the importance of the orbital overlap for the formation of the electric dipole. Because of this small electric dipole moment, bands 1 and 2 have small Rashba splitting. Bands 3 and 4 have more charge along the in-plane direction (more overlap between neighboring orbitals) as well as relatively large in-plane components of the OAM. Therefore they have much larger charge asymmetry along the z-direction and band splitting. The top bands (5 and 6) have small charge asymmetry due to the smallest in-plane component of the OAM. When the crystal momentum k becomes twice larger (k = 0.4π/a in Fig. 3 (b)), the charge asymmetry becomes more significant. This result is consistent with the Rashba splitting being proportional to the k value as shown in Fig. 1. The same trend is observed in Sb single layer. The only difference is that the size of the dipole moment and band splitting is smaller because of the smaller SOC.

Charge density around the Bi atom.

Charge density around the Bi atom in xz-plane when the crystal momentum k is apart from Γ point as much as (a) 0.2π/a and (b) 0.4π/a directed at M point. The numbers indicate the band indices shown in Fig. 1. Red color means dense charge density and blue color is rare charge density.

To ensure the origin of Rashba band splitting, we compare electric dipole energy difference (dots) ΔP · Eext with the Rashba band splitting (solid lines) for both Bi and Sb layers as varying the crystal momentum k from Γ to M point as shown in Fig. 4. Overall, the electric dipole energy difference and the Rashba band splitting are well consistent in all range of crystal momentum for both systems. Small discrepancy can be attributed into two factors. One is the atomic SOC, αL · S. The other is the electric-field screening effect due to charge redistribution in Bi or Sb layers by the external electric field. Mostly, the electric dipole energy difference is larger than the Rashba band splitting in Bi layer. It is mainly because of the screening effect. We confirm that the Rashba band splitting mostly originates from the electric dipole energy difference in both Bi and Sb layers, which are considered as in the strong SOC regime. In the next section, we investigated more on the role of the dipole moment in the Rashba splitting and its correlation to SOC by using tight binding approach.

Tight Binding Analysis

Perturbation theory

We consider a tight binding model for the triangular lattice which consists of Bi or Sb atoms. The electronic properties of them are well-described by p-orbitals while other ones reside in energy levels much far from the Fermi level17. The tight binding Hamiltonian is given by

where H0 is the hopping processes between p-orbitals on the two dimensional triangular lattice without any external fields,  is the atomic spin-orbit interaction and HISB is the ISB term coming from external effects such as electric field or the substrate.

is the atomic spin-orbit interaction and HISB is the ISB term coming from external effects such as electric field or the substrate.

The bare Hamiltonian H0 reads

where λ = x, y, z is the orbital index and σ = ↑,↓ is the spin index. The matrix elements  are given by

are given by

whose long wavelength limits are expressed by

,

,

,

,  and

and  .Here, a = 3(3V1−V2)/8, b = 3(V1−3V2)/8 and

.Here, a = 3(3V1−V2)/8, b = 3(V1−3V2)/8 and  . Other elements (

. Other elements ( and

and  ) are vanishing because the hopping between px or py and pz is forbidden by the symmetry. V1 and V2 represent the σ and π bonding between p orbitals. A set of binding parameters,

) are vanishing because the hopping between px or py and pz is forbidden by the symmetry. V1 and V2 represent the σ and π bonding between p orbitals. A set of binding parameters,  eV and

eV and  eV, yields band structures consistent with the DFT results as shown in Fig. 5. Accurate tight binding parameters are not pursued here since the main purpose of this section is to understand the relation between the dipole energy difference and the Rashba band splitting.

eV, yields band structures consistent with the DFT results as shown in Fig. 5. Accurate tight binding parameters are not pursued here since the main purpose of this section is to understand the relation between the dipole energy difference and the Rashba band splitting.

Electronic structures from tight binding approximation.

Band structures for a set of tight binding parameters  in the unit of eV. The regions in the green boxes in (a) is highlighted in (b). The red dashed bands are obtained from the perturbation theory. For two lowest bands, we plot their OAM (blue) and SAM (red) structures in (c) and (d) each.

in the unit of eV. The regions in the green boxes in (a) is highlighted in (b). The red dashed bands are obtained from the perturbation theory. For two lowest bands, we plot their OAM (blue) and SAM (red) structures in (c) and (d) each.

We suppose that the inversion symmetry with respect to the xy-plane is broken so that

where

which satisfy  for λ ≠ z. Here γ measures the energy scale of the applied electric field. Near Γ point, they are approximated to

for λ ≠ z. Here γ measures the energy scale of the applied electric field. Near Γ point, they are approximated to  . Other matrix elements (

. Other matrix elements ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  ) are vanishing.

) are vanishing.

At Γ point, one can obtain the analytic solution of h0(0) + hSO(0). As an example, we focus on the lowest two degenerate levels for given tight binding parameters above. The eigenenergy is

and corresponding eigenvectors are

where

Then, near Γ point, the other terms h0(k)−h0(0) + hISB(k) can be considered as a perturbation and we obtain effective 2×2 Hamiltonian for those two bands as

where  ,

,  and

and  is the Pauli matrix. The eigenvalues are

is the Pauli matrix. The eigenvalues are

and corresponding eigenvectors are

where  . With these, one can obtain the OAM of each band as follows.

. With these, one can obtain the OAM of each band as follows.

The directions of the OAM of the two lowest bands are opposite to each other when this perturbation scheme is valid.

The results on the electronic structures from our tight binding approximation are presented in Fig. 5. One can note that the tight binding bands and their OAM structures show good agreement with the first-principles results in the previous section. Also, we check the analytic results in the long wavelength limit works very well as indicated by red dotted lines in Fig. 5.

Dipole energy

In this section, we prove that the band splitting is closely related to the dipole energy difference. Here, we regard hISB(k) as a perturbation to explain the splitting of two degenerate multi-orbital bands by the ISB. This is a more general consideration compared with the previous section and its results hold throughout whole Brillouin zone if γ is much smaller than the spin-orbit interaction.

Let us denote the Bloch states on two split bands as  whose spatial representations are given by

whose spatial representations are given by

where λ = x, y, z is the orbital index, ϕλ is the real space wave function of pλ-orbital and ησ is the spinor. Then the dipole energy  becomes

becomes

where the electric field is in z direction ( ). One of the important properties of the p-orbitals is that they cannot give a finite dipole moment if they are in the same site. As a result, the integral of the above is vanishing if R = R′. If we consider the overlaps of wave functions between the nearest neighboring sites as leading contributions,

). One of the important properties of the p-orbitals is that they cannot give a finite dipole moment if they are in the same site. As a result, the integral of the above is vanishing if R = R′. If we consider the overlaps of wave functions between the nearest neighboring sites as leading contributions,

where δ represents the six nearest neighboring sites of each lattice point. In the last integral, one of λ and λ′ (not both) should be z so that the integral is an even function in z direction. Then,

where we have used the fact that ϕλ is an odd function in λ direction. One can note that, when  , the integral

, the integral  is just the hopping parameter

is just the hopping parameter  for the ISB which measures the matrix element of the applied electric potential. If we exploit the vectorial property of p orbitals, the dipole energy becomes

for the ISB which measures the matrix element of the applied electric potential. If we exploit the vectorial property of p orbitals, the dipole energy becomes

Then, the dipole energy difference,  , at each momentum k is

, at each momentum k is

Near Γ point (k α/γ), the eigenvectors for the split bands are just equation (16) and their coefficients satisfy

which lead to

Since this is exactly same with the energy splitting ΔE = ε+−ε− between two bands in equation (15), this proves the origin of the band splitting near Γ point is the formation of the dipole momentum by the ISB terms. The dipole energy splitting is drawn in Fig. 6 as a function of the SOC strength. We note that ΔEd saturate to a finite value ΔEd(α → ∞) = 2γk in the strong SOC limit while it depends linearly on the SOC in the weak SOC region. Although we only considered the lowest bands, we arrive at the same conclusion in the same way for other ones.

In summary, first-principles and tight binding calculations on Bi and Sb triangular monolayers under electric field have been done as model systems. It is shown that the different asymmetric charge distributions are induced for each band given by Rashba splitting and their dipole energies are quantitatively calculated under external electric field. The electric dipole energy difference and the split energy by Rashba splitting give remarkable agreement. Also, the tight binding calculation supports that the Rashba splitting originates from the electric dipole energy difference in the strong atomic spin-orbit coupling regime. We show that the electric dipole energy is mainly responsible for the Rashba band splitting.

Methods

To investigate the surface states of Bi and Sb without bulk state contributions, we considered Bi and Sb triangular monolayers. In order to break the inversion symmetry, we applied an electric field along the direction perpendicular to the layer. For the noncollinear density functional theory (DFT) calculation, we used projector augmented-wave (PAW) method as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)18,19. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)20 was used as exchange correlation functional and the spin-orbit interaction was included. The plane-wave cut off is 450 eV and the convergence criterion for energy is 10−6 eV difference between two sequential steps. First, the volume and internal atomic positions of bulk Bi and Sb were optimized till the internal atomic force becomes less than 10−4 eV/Å. Using this converged cell parameters of aBi = 4.641 Å and aSb = 4.388 Å, we constructed Bi and Sb triangular monolayers under an electric field. We then calculated their band structures and extracted wave function characteristics as well as charge density at a given crystal momentum k and band index n. The wave function characteristics which were calculated by projecting the orbitals onto spherical harmonics of the atom were used to calculate the expectation values of the OAM at a specific k point. From the charge density around a Bi or Sb atom, we calculated the electric dipole moment of the orbital as

where r is the coordinate vector centered at the atom and ρ(r) is the charge density at r.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hong, J. et al. Quantitative analysis on electric dipole energy in Rashba band splitting. Sci. Rep. 5, 13488; doi: 10.1038/srep13488 (2015).

References

Murakawa, H. et al. Detection of Berry’s phase in a bulk Rashba semiconductor. Science 342, 1490–1493 (2013).

Meier, L. et al. Measurement of Rashba and Dresselhaus spin–orbit magnetic fields. Nat. Phys. 3, 650–654 (2007).

Miron, I. M. et al. Current-driven spin torque induced by the Rashba effect in a ferromagnetic metal layer. Nat. Mater. 9, 230–234 (2010).

Miron, I. M. et al. Fast current-induced domain-wall motion controlled by the Rashba effect. Nat. Mater. 10, 419–423 (2011).

Ishizaka, K. et al. Giant Rashba-type spin splitting in bulk BiTeI. Nat. Mater. 10, 521–526 (2011).

Petersen, L. & Hedegård, P. A simple tight-binding model of spin–orbit splitting of sp-derived surface states. Surf. Sci. 459, 49–56 (2000).

Yaji, K. et al. Large Rashba spin splitting of a metallic surface-state band on a semiconductor surface. Nat. Commun. 1, 17 (2010).

Bian, G., Miller, T. & Chiang, T.-C. Rashba splitting and dichroism of surface states in Bi/Ag surface alloy. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 201, 36–41 (2014).

Park, S. R., Kim, C. H., Yu, J., Han, J. H. & Kim, C. Orbital-angular-momentum based origin of Rashba-type surface band splitting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 156803 (2011).

Kim, B. et al. Microscopic mechanism for asymmetric charge distribution in Rashba-type surface states and the origin of the energy splitting scale. Phys. Rev. B 88, 205408 (2013).

Park, S. R. & Kim, C. Microscopic mechanism for the Rashba spin-band splitting: Perspective from formation of local orbital angular momentum. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 201, 6–17 (2015).

Kim, B. et al. Spin and orbital angular momentum structure of Cu(111) and Au(111) surface states. Phys. Rev. B 85, 195402 (2012).

Park, J.-H., Kim, C. H., Rhim, J.-W. & Han, J. H. Orbital Rashba effect and its detection by circular dichroism angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 85, 195401 (2012).

Park, S. R. et al. Chiral orbital-angular momentum in the surface states of Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 046805 (2012).

Jung, W. et al. Warping effects in the band and angular-momentum structures of the topological insulator Bi2Te3 . Phys. Rev. B 84, 245435 (2011).

Reinert, F., Nicolay, G., Schmidt, S., Ehm, D. & Hüfner, S. Direct measurements of the L-gap surface states on the (111) face of noble metals by photoelectron spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 63, 115415 (2001).

Liu, Y. & Allen, R. E. Electronic structure of the semimetals Bi and Sb. Phys. Rev. B 52, 1566 (1995).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This research was mainly supported by Global Frontier Program through the Global Frontier Hybrid Interface Materials (2013M3A6B1078870). CK acknowledges the support from the Converging Research Center Program through the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning, Korea (2013K000312). SRP acknowledges support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2014R1A1A1002440).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. and J.H.S. performed first-principles calculations. J.-W.R. performed tight binding calculations. J.H., J.-W.R., C.K., S.R.P. and J.H.S. prepared the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, J., Rhim, JW., Kim, C. et al. Quantitative analysis on electric dipole energy in Rashba band splitting. Sci Rep 5, 13488 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13488

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13488

This article is cited by

-

Strain-specific impacts of probiotics are a significant driver of gut microbiome development in very preterm infants

Nature Microbiology (2022)

-

Maximal Rashba-like spin splitting via kinetic-energy-coupled inversion-symmetry breaking

Nature (2017)

-

Toward surface orbitronics: giant orbital magnetism from the orbital Rashba effect at the surface of sp-metals

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.