Abstract

Soil respiration, resulting in decomposition of soil organic carbon (SOC), emits CO2 to the atmosphere and increases under climate warming. However, the impact of heavy metal pollution on soil respiration in croplands is not well understood. Here we show significantly increased soil respiration and efflux of both CO2 and CH4 with a concomitant reduction in SOC storage from a metal polluted rice soil in China. This change is linked to a decline in soil aggregation, in microbial abundance and in fungal dominance. The carbon release is presumably driven by changes in carbon cycling occurring in the stressed soil microbial community with heavy metal pollution in the soil. The pollution-induced increase in soil respiration and loss of SOC storage will likely counteract efforts to increase SOC sequestration in rice paddies for climate change mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil respiration, leading to soil organic carbon (SOC) decomposition and CO2 efflux, is a major contributor to the increase in atmospheric CO21. The rate of respiration was known to be influenced by soil temperature and moisture conditions2. Increased soil respiration and thus SOC decomposition under warming, may be responsible for the release of carbon sequestered in the soil, referred to by Schulze and Freibauer3 as “unlocked carbon from soils”.

As a biogenic process, soil respiration is mediated by the soil microbial community and may be sensitive to changes in environmental factors. The role of soil microbial organisms in mediating of the release of biogenic greenhouse gases4 and in providing ecosystem productivity and services5 has been increasingly recognized. Metal pollution is becoming more widespread globally due to economic development and fast urbanization6. However, the understanding of soil microbial responses to heavy metal pollution is still very limited, though it is generally accepted that soil respiration is an indicator of microbial activity in heavy metal affected soils7. Heavy metal pollution may alter the ability of soils to retain carbon, by inducing changes in soil microbial community structure and activity8,9, in microbial abundance and diversity, in metabolic activity and thus in C utilization10.

Until now, evidence on the response of microbial respiration to metal pollution has been conflicting across studies. Whilst reduction in soil respiration, with a consequent reduction in SOM decomposition rate have frequently been observed in forest soils11, in experimentally spiked soils12 and in samples from contaminated fields in laboratory incubations13, very few field studies have suggested a significant influence14,15.

In China, agricultural soils have been shown to be extensively polluted with heavy metal. Rice paddies, mostly distributed in South China, are particularly affected by heavy metal pollution, causing a decline in grain yield and accumulation of toxic metals such as Cd, Pb and/or As in rice grains16. Whereas rice paddies constitute an important part of China’s SOC stock and contribute to C sequestration17, our present understanding of the impacts of heavy metal pollution on biogenic processes of C cycling and greenhouse gas emission in China’s rice paddies is still poor and based on a limited number of field studies.

Here, we report a significant increase in soil respiration and CO2 and CH4 evolution and a concomitant reduction in topsoil C storage from a heavily metal-polluted rice paddy, compared to a nearby control site, from East China. This change is correlated with a significant decline in fungal abundance in the reduced microbial community and decreased soil aggregation in the polluted soil. The study shows the sequestered carbon can be unlocked in metal polluted croplands, due to a modified soil C cycling within the stressed soil microbial community.

Results

Micro-aggregate size

As shown in Table 1, analysis of micro-aggregate size fraction distribution showed a decline by 39.4% in the share of large sized micro-aggregates (>0.2 mm) in the topsoil under heavy metal pollution.

Microbial abundance and community structure

A significant reduction in the microbial community abundance and structure was observed in metal polluted soil (Table 2). A decline was seen in polluted (PF) over background (BG) field, by 22% in soil microbial biomass C and by 43% in total extractable microbial phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) (Table 2). Moreover, a marked shift in the soil microbial community was visible in PF plots with a 23% decrease in microbial C/N ratio together with a significant decline in fungal-to–bacterial ratio in PF over BG plots across the biological assays. This was shown by a 58% and 76% decline in cultivable organisms (Table S7), a 6.3% and 21% decrease in extractable PLFAs respectively in rice and wheat fields and a 5% decrease in gene copy numbers in the rice field (Table 2).

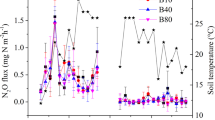

Soil respiration and CO2 emission

Soil respiration and CO2 emission rates were variable over the whole crop growing season (WCGS) but were consistent in showing that heavy metal pollution significantly increased respiration rates (Fig. 1). Soil CO2 and CH4 efflux across the WCGS was increased under pollution by 69% and 14% in the rice season and soil CO2 efflux by 13% in the wheat season, respectively (Fig. 1, Table S1 and S2). There was an increase in soil basal respiration from PF plots compared to BG plots by 46% and 12% (Table S3 and S4), respectively under aerobic and anaerobic incubation for the topsoil samples from the wheat field and rice field during grain heading and by 4% and 6% (Tabel S5 and S6) under aerobic incubation for the topsoil samples from the wheat field and rice field after harvest.

SOC pool

Given soil respiration and CH4 emissions were significantly increased when soil was polluted by heavy metal, 12% and 11% net loss of topsoil SOC were observed in PF of rice field and wheat field compared to BG plots (Table 3). Meanwhile, microbial biomass C and N also showed a decrease in PF compared to BG.

Discussion

Heavy metal pollution has been identified as a severe environmental issue for the potential hazards on environmental health and food safety. However, the knowledge of the effect of heavy metal pollution on SOC decomposition was limited. Zhang et al.18 resulted that heavy metal pollution increased basal respiration and qCO2 and decreased microbial biomass C and N in mining soils. Dumat et al.19 reported a decrease in SOC stock in croplands under multiple metals pollution. Being a main result of this study, marked increases in soil respiration and CO2 effluxes with heavy metal pollution were observed in a rice paddy. The increased respiration was accompanied by a concomitant 12% net loss of topsoil SOC in pollution field compared to background field. Accounting for 80% of the nation’s rice grain production, rice paddies had been increasingly polluted with heavy metals in major rice cultivation regions of China20,21. Heavy metal contamination in rice paddies could result in enhanced hazard for human health through soil-food chain transfer22. Given the decrease in SOC in polluted soil, heavy metal contamination may speed up climate change according to the results by this study. Meanwhile, a decrease in the proportion of large sized micro-aggregates was observed in polluted soils, which indicates a destruction of soil structure by heavy metal contamination. Given these, heavy metal contamination may cause multi-risks on food security, soil health and climate change.

Soil microorganism, which plays key roles in organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling, is an important component of terrestrial ecosystems. There has been an increasing attentions evidenced that microorganisms are much sensitive to heavy metal stress in soils18,23. In this experiment, microbial biomass C significant decreased by 24% and by 22% in the field of rice season and wheat season, respectively. The reasons are possibly due to microorganisms in soil under heavy metal stress diverting energy from growth to cell maintenance functions24. Moreover, in heavy metal polluted soils, microorganisms need to exhaust more energy to survive in unfavorable conditions while they are stressed with metal toxicity, which is supported by the lower soil microbial quotient in polluted soils (Table 3). As a result of high metabolic quotient, a higher percentage of consumed carbon is released as CO2 and less C and N are built into organic components25. Data mentioned above could partly explain why soil respiration increased and SOC and SMBC decreased in metal polluted soil compared to background soil.

The decrease in SOC here is linked to a reduction not only in microbial abundance, but a decline in fungal-to-bacterial ratio in PF plots over BG plots (Table 2). This change is consistent with our previous finding of a cross site study of metal-polluted rice croplands from South China26. Cotrufo et al.11 reported a similar microbial community change with forest soils but with decreased respiratory C loss. Fungi-dominated microbial communities have been known to lower SOM decomposition rates in C cycling studies8,27 and in experiments with long term fertilization trails26 and with heavy metal affected soils11,13. In this study, nevertheless, the stressed microbial community change is characterized by a significant lower F/B ratio across different assays. Fungi in soil contribute to building-up large sized micro-aggregates28 and the reduction in cultivable fungi community could induce a decrease of large sized micro-aggregates, which has been observed in the polluted fields as shown in Table 1. As well known, soil organic matter can be physically protected with aggregates with the process inhibiting microbial access to the organic substrate29,30. Furthermore, large sized micro-aggregates play an important role in SOC sequestration, which have been shown in maize fields under tillage experiments from the USA31 and in rice paddies under long term organic/inorganic combined fertilization experiments32. This study indicates a marked decrease in the proportion of large sized micro-aggregates in heavy metal polluted soils (Table 1). Here, a combination of increased metabolic respiration and decreased physical protection could explain the overall increased soil respiration and in turn, the significant reduction in SOC storage due to enhanced SOC decomposition under metal pollution. Thus, we propose a modified engine as a mechanism for changes in biogenic processes of C cycling, with a decline in fungal dominance of the stressed soil microbial community driven by metal pollution in the rice soil (Fig. 2).

Extrapolating from the changes in CO2 efflux across WCGS, an increase in CO2 emission from PF plots over BG plots could amount to 0.2 t C ha−1 yr−1, over a whole rice/wheat rotation. This increase is significant to the estimated mean soil respiration rate of 1.7 t C ha−1 yr−1 33. An annual SOC sequestration from rice paddies was reported in a range of 0.13–2.2 t C ha−1 yr−1 across mainland China17 and of 0.16 t C ha−1 yr−1 particularly for the Jiangsu Province23, where this study is located. Thus, the increased CO2 emission with metal pollution could potentially counteract the SOC sequestration in rice paddies, raising a critical challenge for food production and climate change mitigation in China’s rice agriculture.

In conclusion, metal pollution in the rice paddy has increased soil respiration and CO2 emissions with a concomitant decline in soil organic carbon storage. This is linked to a decline in the abundance of microbes and a reduction in fungal dominance of the stressed soil microbial community under metal pollution. This study highlights the need for serious consideration of metal pollution-induced changes in metabolic activity of decomposers in SOM stabilization and global C cycling modeling.

Thus, protection of paddy fields from heavy metal pollution and restoration of those soils that are already polluted, could have a significant impact upon the ability of cropland soils to sequester carbon, as well as help them to sustain the high productivity essential to China’s food security.

Methods

Site and soil

The study site was in Yifeng Village, Xushe Township, Yixing Municipality (N 31° 24′, E 119° 41′), Jiangsu, China. The soil was a typical paddy soil, classified as a Fluvaquent. The local climate was a subtropical monsoon climate with a rainy and hot summer and a cool and relatively dry winter. The soil has been cultivated with a summer rice-winter wheat rotation for a number of decades (SI). Since the late 1960’s, the area has experienced industrial development and heavy metal pollution of multiple elements has occurred in part of the area adjacent to a metal smelter. From this area, the basic properties are similar, but the levels of metal accumulation of Pb, Cd Hg and As are divergent across plots. We used randomly selected polluted plots (downwind of the smelter) and relatively unpolluted ones (upwind of the smelter), with a distance of 600 m apart (SI), for a comparative study of soil respiration.

Soil sampling and basic property measurement

Topsoil (0–15 cm) samples were collected in triplicate on each plot using an Eijkelkamp soil core sampler for lab incubation of basal respiration and basic properties as well as metal concentrations. For soil sample treatment, lab analysis of soil basic properties and metal contents, we followed the recommended protocols by Lu34 (SI). Undisturbed soil cores were untreated for soil aggregation analysis.

For basic properties, measurement and metal contents, samples were taken after wheat harvest, while soils for respiration testing and for microbial study were taken at different times with crop growth. For microbial studies, samples were collected with a stainless steel shovel in 5 random replicates to form a composite sample each plot. Samples were stored in sterilized closed plastic bags in an ice box for shipping and stored at 4 °C prior to incubation within 7 days.

Chemical determinations

We measured SOC content using wet digestion with H2SO4-K2Cr2O7, titration with FeSO4 (SI); We performed digestions with a mixed acid solution of HF-HClO4-HNO3 (8:2.5:2.5, v:v:v), HCl-HNO3 (1:1, v/v) and HNO3-HClO4-HF (8:1:2, v/v/v) respectively for Cu, Pb, Cd, Zn, Cr, Ni, for As, Hg and for Se. The contents in the digestions were determined with atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS) with atomic fluorescence spectrophotometer (AFS) for Hg, As and Se (SI). The measured soil properties and metal contents in given in Table 4 and 5.

Field CO2 efflux measurement

We performed monitoring of soil CO2 efflux from soil respiration with a static closed chamber in triplicates on each plot, both for the polluted and control (background) fields in week interval during the whole crop growing season (WCGS) of a crop rotation year of rice and wheat. In each plot, three plastic flux collars (0.35 m × 0.35 m × 0.25 m) were permanently installed inter-rows over the whole annual cropping year. Gas was sampled during 9–11 AM over the rice season and during 1–3 PM over the wheat season. A gas sample was taken respectively at 0, 10, 20 and 30 min after chamber closure. Fluxes were determined from the slope of the mixing ratio change in these four samples. CO2 concentrations (and CH4 from rice field) of the gas samples were analyzed with a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890 A) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and an electron capture detector (ECD). Seasonal total flux of CO2 (and CH4 during rice growing) was sequentially accumulated from the emissions between every two adjacent intervals of the measurements. Soil temperature and moisture contents were also measured in situ with a Moisture Meter Type HH2. The setting of the chambers and the gas sampling and measurement is described in detail in SI.

Measurement of basal respiration

Soil basal respiration was determined by lab incubation in a LRH-250-S incubator (Medicine Machinery Co. Ltd., Guangdong, China) at 25 °C ± 1.0 °C constantly for 28 days. We performed aerobic incubation consistently under water holding capacity (WHC) of 60% for samples both from the rice and wheat seasons, while anaerobic incubation constantly water submerged only for samples from the rice season. The incubations were done with 20 g of topsoil in a sealed jar and gas evolved in the headspace was collected every day during incubation course by syringe pressure. The gas concentration was determined with the same method as for field gas sample. The procedure was reported in a previous study35 and given in detail in SI. The soil basal respiration rate in a given time interval was calculated from the quantity of CO2 evolved and normalized on the basis of the mean SOC contents of the sample (SI).

Analysis of size fractions of soil micro-aggregates

Soil aggregation is much influenced by SOC content and fungal activity. We analyzed size fractions of soil micro-aggregates of undisturbed topsoil cores using a fractionation procedure with low energy dispersion developed by Stemmer et al.36 with minor modifications by Sessitsch et al.37. This procedure was reported in a previous study35 and given in detail in SI.

Microbiological and biochemical analysis

We use a couple of standard microbiological assays (SI) to infer the changes in microbial community and structure with metal pollution. All the details are described in a recent work by Liu et al.38. Fresh samples (within 1 day of collection from the fields, See SI) were used for analyzing soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen, which was done with a fumigation and extraction procedure39. Microbial C content was determined with TOC analyzer (Jena MultiN N/C 2100, 2005) and N was determined with micro-Kjeldahl method. DOC was measured with a K2SO4 extraction and determined with TOC analyzer (Jena Multi N N/C 2100, 2005).

Culturable microbial population was analyzed with a procedure of dilute plate counting, basically following the procedure recommended by Zuberer40. Microbial phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) extraction and determination was performed for the same samples as for culturable organisms (SI), following a procedure described by Stemmer et al.12 (SI).

Total soil DNA was extracted with PowerSoil™ DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories Inc., CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each DNA sample was amplified with F968 and R1401 set specifically for the bacterial community and the NS1 and Fung-GC set specifically for the fungal community. With a real-time PCR (qPCR) assay of bacteria and fungi, the copy numbers of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the fungal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rRNA gene in all the soil samples were determined in triplicate using an iCycler IQ5 Thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The quantification was based on the fluorescent dye SYBR-green one, which binds to double stranded DNA during PCR amplification. The primers and the thermal cycling conditions were as described by Fierer et al.41.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bian, R. et al. Does metal pollution matter with C retention by rice soil? Sci. Rep. 5, 13233; doi: 10.1038/srep13233 (2015).

References

Schlesinger, W. H. & Andrews, J. A. Soil respiration and the global carbon cycle. Biogeochem 48, 7–20 (2000).

Yuste, J. C. et al. Microbial soil respiration and its dependency on carbon inputs, soil temperature and moisture. Glob. Change Biol. 13, 1–18 (2007).

Schulze, E. D. & Freibauer, A. Environmental science: Carbon unlocked from soils. Nature 437, 205–206 (2005).

Post, W. M. & Venterea, R. T. Managing biogeochemical cycles to reduce greenhouse gases. Front. Ecol. Environ. 10, 511–511 (2012).

Van Der Heijden, M. G. A., Bardgett, R. D. & Van Straalen, N. M. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 11, 296–310 (2008).

Grimm, N. B. et al. The changing landscape: ecosystem responses to urbanization and pollution across climatic and societal gradients. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6, 264–272 (2008).

Brookes, P. C. The use of microbial parameters in monitoring soil pollution by heavy metals. Biol. Fert. Soils. 19, 267–279 (1995).

Kandeler, E. et al. Transient elevation of carbon dioxide modifies the microbial community composition in a semi–arid grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40, 162–171 (2007).

Chen, Y. P., Liu, Q., Liu, Y. J., Jia, F. A. & He, X. H. Responses of soil microbial activity to cadmium pollution and elevated CO2 . Sci. Rep. 4, 4287, 10.1038/srep04287 (2014).

Moynahan, O. S., Zabinski, C. A. & Gannon, J. E. Microbial community structure and carbon–utilization diversity in a mine tailings revegetation study. Restor. Ecol. 10, 77–87 (2002).

Cotrufo, M. F., Desanto, A. V., Alfani, A., Bartoli, G. & De Cristofaro, A. Effects of urban heavy–metal pollution on organic–matter decomposition in Quercus–Ilex L woods. Environ. Poll. 89, 81–87 (1995).

Stemmer, M., Watzinger, A., Blochberger, K., Haberhauer, G. & Gerzabek, M. H. Linking dynamics of soil microbial phospholipid fatty acids to carbon mineralization in a 13C natural abundance experiment: Impact of heavy metals and acid rain. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 3177–3186 (2007).

Niklinska, M., Chodak, M. & Laskowski, R. Characterization of the forest humus microbial community in a heavy metal polluted area. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37, 2185–2194 (2005).

Kandeler, F., Kampichler, C. & Horak, O. Influence of heavy metals on the functional diversity of soil microbial communities. Biol. Fertil. Soils 23, 299–306 (1996).

Murray, P., Ge, Y. & Hendershot, W. H. Evaluating three trace metal contaminated sites: a field and laboratory investigation. Environ. Poll. 107, 127–135 (2000).

Wei, B. G. & Yang, L. S. A review of heavy metal contaminations in urban soils, urban road dusts and agricultural soils from China. Microchem. J 94, 99–107 (2010).

Pan, G., Li, L., Wu, L. & Zhang, X. Storage and sequestration potential of topsoil organic carbon in China’s paddy soils. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 79–92 (2003).

Zhang, F. P. et al. Response of microbial characteristics to heavy metal pollution of mining soils in central Tibet, China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 45, 144–151 (2010).

Dumat, C., Quenea, K., Bermond, A., Toinen, S. & Benedetti, M. F. Study of the trace metal ion influence on the turnover of soil organic matter in cultivated contaminated soils. Environ. Poll. 142, 521–529 (2006).

Wong, S. C., Li, X. D., Zhang, G., Qi, S. H. & Min, Y. S. Heavy metals in agricultural soils of the Pearl River Delta, South China. Environ. Pollut. 119, 33–44 (2002).

Hang, X. S. et al. Risk assessment of potentially toxic element pollution in soils and rice (Oryza sativa) in a typical area of the Yangtze River Delta. Environ. Pollut. 157, 2542–2549 (2009).

Chaney, R. L. et al. An improved understanding of soil Cd risk to humans and low cost methods to phytoextract Cd from contaminated soils to prevent soil Cd risks. BioMetals 17, 549–553 (2004).

Liao, Q. et al. Increase in soil organic carbon stock over the last two decades in China’s Jiangsu Province. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 861–875 (2009).

Killham, K. Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal mediation of trace and minor element uptake in perennial grasses: relation to livestock herbage. In Ecological Interactions in Soil: plants, microbes and animals (eds Fitter, A. H. et al. ) 225–232 (Blackwell, 1985).

Mikanova, O. Effects of heavy metals on some soil biological parameters. J. Geochem. Explor. 88, 220–223 (2006).

Liu, D. W. et al. SOC accumulation in paddy soils under long–term agro–ecosystem experiments from South China. VI. Changes in microbial community structure and respiratory activity. Biogeosci. Disc. 8, 1529–1554 (2011).

Butler, J. L., Williams, M. A., Bottomley, P. J. & Myrold, D. D. Microbial community dynamics associated with rhizosphere carbon flow. Appl. Environ. Microb. 69, 6793–6800 (2003).

Schulten, H. R. & Leinweber, P. New insights into organic–mineral particles: composition, properties and models of molecular structure. Biol. Fertil. Soils 30, 399–432 (2000).

Schmidt, M. W. et al. Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 478, 49–56 (2011).

Zimmermann, J., Dauber, J. & Jones, M. B. Soil carbon sequestration during the establishment phase of Miscanthus×giganteus: a regional-scale study on commercial farms using 13C natural abundance. GCB Bioenergy 4, 453–461 (2012).

Mikha, M. M. & Rice, C. W. Tillage and manure effects on soil and aggregate–associated carbon and nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. AM. J 68, 809–816 (2004).

Zhou, P., Song, G. H., Pan, G., Li, L. & Zhang, X. SOC accumulation in three major types of paddy soils under long–term agro–ecosystem experiments from South China: physical protection in soil micro–aggregates. Acta Ped. Sin. 45, 1063–1071 (2009).

Bachelet, D., Kern, J., Tölg, M. Balancing the rice carbon budget in China. Ecol. Model. 79, 167–177 (1996).

Lu, R. K. Methods of Soil and Agro-chemical Analysis. China Agric Sci Tech Press, Beijing (in Chinese) (2000).

Zheng, J., Zhang, X., Li, L., Zhang, P. & Pan, G. Effect of long-term fertilization on C mineralization and production of CH4 and CO2 under anaerobic incubation from bulk samples and particle size fractions of a typical paddy soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 120, 129–138 (2007).

Stemmer, M., Gerzabek, H. & Kandeler, E. Organic matter and enzyme activity in particle-size fractions of soils obtained after low-energy sonication. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30, 9–17 (1998).

Sessitsch, A., Weilharter, A., Gerzabek, M. H., Kirchmann, H. & Kandeler, E. Microbial Population Structures in Soil Particle Size Fractions of a Long-Term Fertilizer Field Experiment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 4215–4224 (2001).

Liu, Y. Z. et al. Decline in topsoil microbial quotient, fungal abundance and C utilization efficiency of rice paddies under metal pollution across South China. PLoS One 7, e38858 (2012).

Vance, E. D., Brookes, P. C. & Jenkinson, D. S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 19, 703–707 (1987).

Zuberer, D. A. Recovery and Enumeration of Viable Bacteria. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2-Microbiological and Biochemical Properties. (eds Weaver, R. W. et al. ) 119-144 (Soil Science Society of America, 1994).

Fierer, N. & Jackson, R. B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 626–631 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The research work was supported by the China Natural Science Foundation under a grant number of 40830528 and of 40671180. P.S. is a Royal Scoiety-Wolfson Research Merit Award holder and was supported by additional travel funds from a UK BBSRC China Partnership Award. P.S.’s contribution was supported by the UK-China Sustainable Agriculture Innovation Network (SAIN). D.C. was supported by an additional travel and collaboration funding from the China Ministry of Education under a “111” project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P. designed research; R.B., K.C., Z.L., Y.L., L.Z. and X.Y. performed the research respectively with data analysis, field measurement, microbial biology and biochemical assays, chemical and aggregate analysis and lab incubation; R.B., K.C., X.L., L.L., J.Z., G. P., X.Z., G.P., Q.H. and X.Y. analyzed the data; G.P., D.C. and P.S. wrote the paper with discussions.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bian, R., Cheng, K., Zheng, J. et al. Does metal pollution matter with C retention by rice soil?. Sci Rep 5, 13233 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13233

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13233

This article is cited by

-

Effects of bagasse biochar application on soil organic carbon fixation in manganese-contaminated sugarcane fields

Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture (2023)

-

Carbon and nitrogen cycling in a lead polluted grassland evaluated using stable isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) and microbial, plant and soil parameters

Plant and Soil (2020)

-

Biochar amendment of chromium-polluted paddy soil suppresses greenhouse gas emissions and decreases chromium uptake by rice grain

Journal of Soils and Sediments (2019)

-

Trichoderma for climate resilient agriculture

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2017)

-

Toxic metal tolerance in native plant species grown in a vanadium mining area

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.