Abstract

To explore the effect of morphology on catalytic properties of graphitic carbon nitride (GCN), we have studied oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) performance of two different morphologies of GCN in alkaline media. Among both, tubular GCN react with dissolved oxygen in the ORR with an onset potential close to commercial Pt/C. Furthermore, the higher stability and excellent methanol tolerance of tubular GCN compared to Pt/C emphasizes its suitability for fuel cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A global energy crisis due to significant increase in industrial activities is a great challenge for future science. The depletion of fossil fuels is driving scientists to develop renewable and highly efficient methods for energy production and storage such as fuel cells, supercapacitors and lithium batteries which have proved to be favorable candidates in this aspect1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Among these, fuel cell got tremendous attentions of researchers due to its high efficiency and environment friendly nature. Fuel cells normally produce current by the electrochemical catalytic oxidation of a fuel, like ethanol, hydrogen or methanol at the cell cathode4,5,6,7,8,9. Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) considered as a key factor in order to investigate the performance of fuel cell. Therefore, efficiency of ORR strongly depends on the catalyst used8,9,10. Nobel metals like Pt have been extensively studied as catalysts for ORR but high price, rare abundance, low stability, rapid degradation against carbon monoxide impurity, sluggish ORR kinetics needs high Pt loading to achieve acceptable power density and fuel crossover effect are the main hurdles in their practical applications8,9,10. Furthermore, Pt-based catalysts usually suffer from particle dissolution, surface oxide formation and aggregation in alkaline electrolytes9,10. In contrast, non-precious transition metals, metal oxides, chalcogenides and their composites with carbon materials bring an advantageous improvement in the stability and crossover effect of fuels11,12,13,14. Despite wide abundance and good reaction kinetics, metal-based electrode materials still have several disadvantages, such as poor durability in strong acidic or basic environment, relatively high cost and detrimental environmental effects11,12,13,14,15. Thus, for the realization of fuel cells, it is necessary to develop stable metal-free ORR catalysts. Therefore, development of high performance, low cost and environment benign metal free catalysts are of great importance for fuel cells.

In this regard carbon based materials have been explored as active electrocatalysts. Introduction of heteroatoms such as nitrogen/sulphur/phosphorous in the carbon structure has also lead to significant improvements in electrocatalytic performances of carbonaceous materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene15,16. Heteroatom-doping can enhance the electron-donor ability and improve their conductivity and catalytic properties by breaking the density of state (DOS) and electroneutrality of graphitic electronic cloud16,17,18. Among different heteroatom-doping, nitrogen-doping brings much improved results due to its higher electronegativity that cause net positive charge on the carbon atoms in its vicinity19,20. Thus, several nitrogen-doped carbon nanostructures such as graphene, CNTs and ordered mesoporous carbon have been studied for ORR that shows good catalytic activity19,20,21,22. However, a rational design of structure and morphology is required to improve the catalytic performance of these carbon-based materials. Thus, the introduction of graphitic carbon nitride (GCN) is a key solution to these issues19,20,21,22. The GCN has high nitrogen content, easily tuneable structure, cost effectiveness and environment friendly nature, which are potentially appropriate for ORR23,24,25,26. But the template based synthesis to develop its different morphology is disadvantageous as strong acids are needed to remove or etch the template13,23,24,25,26. Thus, template-free synthesis with unique one-dimensional (1D) nanostructures is highly required to improve the performance and its realization as cathode in fuel cells. The 1D nanostructures of GCN have large aspect ratio, high surface area, large number of active sites and short diffusion path for electrons and electrolyte/ions that are favourable for high performance as ORR catalyst in comparisons to previously reported bulk or powder carbon nitride (CN)23,24,25,26.

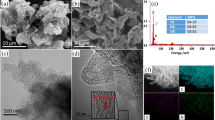

Herein, we present the template-free synthesis of 1D graphitic carbon nitride (GCN) in the form of nanofibers (GCNNF) and tubular (TGCN) as shown in Fig. 1. The products showed high surface area and high nitrogen contents that increase the wettability of the electrode and enhance the active sites which improve the overall performance, respectively. It was found that tubular structures exhibit higher ORR activity than nanofibers because of the availability of more active sites, higher surface area which increases electrolyte-electrode contact, highly accessible active sites and shorter diffusion path. Furthermore, GCNs followed the two and four electron pathway in the alkaline media with an onset potential close to that of commercial Pt/C. The stability of the GCNs is higher than that of Pt/C and exhibit excellent methanol tolerance. It is worth mentioning that morphology based studies of GCN will provide an understanding to manipulate the various materials to achieve maximum catalytic performance.

Results

The structural analysis of GCNNF and TGCN were done using X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectroscopy as shown in Fig. 1a. XRD patterns of both samples clearly show the single well-defined broad peak at 27.3° corresponding to graphitic phase of carbon nitride and recognized as g-(002) with inter-planar distance of d = 0.326. These peaks are originated due to the long-range inter-planar stacking of aromatic systems14,23. The morphological aspects of TGCN and GCNNF were characterized using scanning electron microscope (SEM). Figure 1b and S1 are representing the tubular structure of TGCN with average length of ~15 μm and diameter of ~0.8 μm. Figure 1c and S2 clearly depicts the fiber like structure of the GCNNF which grew randomly with average diameter of ~150 nm and length ~20 μm. In order to further confirm the tubular structure of TGCN, transmission electron microscope (TEM) of the TGCN has been performed as shown in Fig. 1d. From the TEM image, it is obvious that TGCN were grown with the smooth surface and well-defined interior tubular structure. Furthermore, TEM studies show that as-synthesized TGCN has highly porous tube walls, which can accelerate the efficient transfer of mass in the electrode.

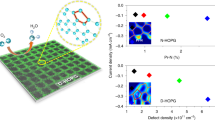

Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was utilized to characterize the chemical bonds present in TGCN as shown in Figure S3. An absorption peak around 800 cm−1 is the strong indication of the heterocycles present in GCN, these peaks are due to the breathing mode of s-triazine and sp2 C = N27,28. The small peaks at 1060, 1260 and 1324 cm−1 shows the existence of single C–N bonds28. The peaks at 1367, 1382 and 1420 cm−1 are due to amorphous sp3 C–C bonds27,28. The peaks relevant to the stretching vibration modes of NH2 and NH groups are observed in the range of 3000–3500 cm−1 27,28. Furthermore, to investigate the chemical compositions and the nature of chemical bonding of constituent elements in as-prepared GCN, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted as shown in Fig. 2a–d. The full scan spectrum of XPS analysis reveals the existence of core levels of C, O and N in both GCN, which confirm the high purity of the as-prepared products (Figure S5 & S6). The de-convolution of C 1s peak (Fig. 2a,b) provides evidence for the presence of different chemical states of carbon in the as-synthesized products, the peak at 284.88 eV corresponds to sp2-hybridized carbon bonded to N atom in an aromatic ring, whereas second peak at 288.18 eV corresponds to C-N bonding in GCN. The nature of nitrogen species strongly effect the catalytic properties of carbon catalyst, thus de-convoluted N1s peaks of TGCN and GCNNF are presented in Fig. 2c,d, respectively. The peaks present at 400.8, 399.6, 398.6, 397.8 eV in TGCN and 400.6, 399.6, 398.8, 398 eV in GCNNF are corresponding to graphitic, pyrolic, amino and pyridinic nitrogen centers, respectively2,29. The percentage of each type of nitrogen is presented in Table S1, from where it is obvious that TGCN contains higher concentration of pyridinic nitrogen while GCCNF contains little higher concentration of graphitic nitrogen. The existence of large concentrations of pyridinic nitrogen and amino groups along with oxygen functionalities correspond to the better performance as cathodic ORR electrocatalysts. It is worth noting that the presence of graphitic and amino nitrogen determines the onset potential and electron transfer number in ORR process, while the enhanced oxygen reduction current density is ascribed to the total content of graphitic and pyridinic N.

The exposed surface of a material determines its ability to catalyse the reaction thus surface area measurements of TGCN and GCNNF were determined through Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method in the relative pressure range of 0–1. The measured surface area of TGCN is 32.27 m2/g that is higher than that of GCNNF (12.96 m2/g) as shown in Fig. 3a, The higher surface area of TGCN shows that it has large exposed surface with higher active sites to catalyse the oxygen in ORR process and provides large space to accommodate more charge storage sites. The elemental mapping analysis of TGCN was done using scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) that confirms the spatial distribution of carbon, nitrogen and small amount of oxygen which are consistent with XPS results that can be seen in Fig. 3b–e. Raman spectroscopy was utilized to further confirm the structure of carbon nitrides (TGCN and GCNNF) as shown in Figure S4. Where the broad peak appearing in the 1250–3000 cm−1 region are associated with the overlap of several of N-related peaks (N = C = N, 1400 cm−1; –CN, 1600 cm−1; atmospheric stretching vibration, 2300 cm−1)30.

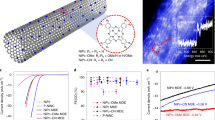

The ORR electrocatalytic activity of TGCN was investigated through loading the active materials on glassy carbon electrode for cyclic voltammetry (CV) in O2 saturated 0.1M KOH aqueous solution as shown in Fig. 4a. The CV of TGCN in O2 saturated solution clearly revealed its ORR catalytic activity with distinctive ORR onset potential around −0.15 V vs. Ag/AgCl and the peak current at the potential of −0.39 V vs. Ag/AgCl. The onset potential is calculated where 10% of the current value is achieved at the peak potential. Rotating disk electrode (RDE) measurements are further executed to scrutinize the ORR activity and kinetics of the TGCN and GCNNF 1 D nanostructures in O2 saturated 0.1 M KOH solution. Linear sweep voltammograms (LSV) for TGCN and GCNNF were recorded at 1600 rpm and compared with commercial Pt/C, as shown in Fig. 4b. The onset potential for TGCNF and CNNF were found to be ca. −0.15 and −0.14 V, respectively in comparison to commercial Pt/C (−0.02). The slightly better onset potential of GCNNF than TGCN is attributed to presence of higher concentration of graphitic and amino nitrogen but the higher current density of TGCN is due to higher concentration of pyridinic nitrogen (Table S1), large surface area and tubular morphology which provides large adsorption of oxygen and large active sites for the reduction of oxygen. Although, the current density is based on the concentration of oxygen and its reduction on the electrode-electrolyte interface but here when both samples (GCNNF and TGCN) were tested under same condition higher current density was found for TGCN because of the aforementioned reasons29. A better performance of both 1D nanostructures is based on the presence of higher content of nitrogen that disturbed the electronic structure of graphitic carbon and its DOS resulting in higher active sites with better performance. Furthermore, the interior tubular structure of TGCN shortened the diffusion path by providing dual pathway (from inside and outside of the tube) for diffusion and increased the electrolyte-electrode contact area. As a result, better catalytic activity with higher current densities was observed for TGCN. Furthermore, presence of oxygenated groups on the surface GCN nanostructures (as witnessed by XPS) further reduces the charge transfer resistance by providing more active sites on the surface of the electrode5.

In addition, LSVs were also recorded for TGCN and GCNNF from 400 to 2500 rpm to explore the exact kinetic parameters including electron transfer number (n) and kinetic current density (JK) using Koutecky–Levich (K-L) equations, shown in supporting information. It is worth noting that with increasing rotation speed the current density is increased for both 1D nanostructures due to availability of large diffused oxygen4. The calculated current densities at different potentials and rotation speeds are presented in the Fig. 4c,d for TGCN and GCNNF, respectively. From the current density values it is noted that the TGCN shows larger current densities as compared to GCNNF because of its tubular structure that shortened the diffusion pathways for dissolved oxygen and provides large active sites for its reduction. However, in case of GCNNF only surface reaction was observed that also limit the reaction transfer kinetics that was further supported by n calculations.

From the n calculation (according to K-L equation presented in supporting information) it is also concluded that GCNNF only possess two electron transfer process throughout all potential range. In contrast to GCNNF, TGCN shows two and four electron transfer processes per oxygen molecules (Figure S8 and S9). The higher n values and larger current density of TGCN with superior onset potential emphasize that tubular structure is more feasible for higher performance as electrode of ORR rather than fibrous one. Furthermore, an interesting phenomenon was observed that higher n value is found as potential moves towards negative5. Further, n calculation demonstrate that in case of GCNNF, formation of intermediate product (peroxide, H2O2) is found by the partial oxidation of oxygen as it shows transfer of two electron that is insufficient for complete reduction of oxygen instead of four electron that is the desired n value for better performance of fuel cells. But in case of TGCN ORR reaction proceeds through transfer of four electrons that proves inhibition of intermediate products and carried out the complete reduction of oxygen to water.

Moreover, for the sake of comparison the TGCN 1D nanostructure and commercial Pt/C catalysts are further tested for methanol crossover via chrono-amperometric responses at the potential of −0.25 V in O2 saturated 0.1 M KOH electrolyte (Fig. 5a). Because one of the major hurdles in long cyclic performance of commercial Pt/C as cathodic ORR catalysts is that its performance is drastically affected with the addition of methanol. It is observed that the current decayed in similar fashion for the TGCN 1D nanostructure and commercial Pt/C catalysts before methanol addition. However, after the addition of 3 M methanol a drastic change in current decay is observed for commercial Pt/C catalyst shows a rapid drop in performance and initiation of methanol oxidation reaction (MOR), while that of the TGCN 1D nanostructure shows stable amperometric response even after addition of 2 wt% methanol. This indicates that the TGCN structure owns excellent methanol tolerance, which strongly emphasizes its use for practical applications. Furthermore, the durability of the TGCN 1D nanostructure was examined in 0.1M KOH for 20,000 s and it is found that the TGCN 1D nanostructure is more stable in basic medium than the commercial Pt/C (Fig. 5b & S10). The higher values of relative current for the TGCN 1D nanostructure than Pt/C after 20,000 s confirms its superior stability than Pt/C. Such high durability of the TGCN 1D nanostructure is due to its unique tubular structure that provides higher contact area between electrode and electrolyte and larger active sites for ORR. Therefore, the TGCN 1D structure synthesized in present work is a promising electrocatalyst for ORR in fuel cells. Although the onset potential of TGCN 1D nanostructure is slightly lower than Pt/C but its high stability and very good methanol tolerance emphasize its dominance over Pt/C and prove it to be a better contestant in the ORR. Furthermore, to investigate the reason for better performance of TGCN than GCNNF, also over all better stability with improved current density, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was carried out. The Bode (Fig. 6c) and Nyquist (Fig. 6d) results confirm that TGCN exhibits much better overall conductivity than that of GCNNF; therefore, the enhanced ORR performance both in current density and electron transfer number is attributed to its lower resistance to electron and faster mass transport. However, the enlarge Nyquist spectrum (inset of Fig. 6d) shows that Pt/C bears lower charge transfer resistance (Rct) than both of the GCN structures but the more straight inclined line in the higher frequency region proved that GCN offers much lower resistance (Warburg impedance (W)) for mass transport and higher wettability of the electrode.

(a) CV of TGCN in 0.1 M KOH solution at scanning rate of 100 mV/s (b) LSV curves of TGCN, GCNNF and Pt/C electrodes in an O2 saturated 0.1 M KOH solution at a scanning rate of 10 mV/s and a rotation speed of 1600 rpm (c,d) RDE curves of TGCN and GCNNF electrode in an O2 saturated 0.1 M KOH solution with different rotation speeds at a scanning rate of 10 mV/s respectively.

(a) Methanol crossover effect test of PG and Pt/C upon addition of 3 M methanol after about 10 min in an O2 saturated 0.1 M KOH solution at −0.25 V. (b) Current-time response of TGCN and Pt/C electrodes at −0.5 V in an O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a rotation speed of 1600 rpm. Bode (c) and Nyquist (inset is the enlarge spectrum in lower frequency) (d) spectra of TFCN, FGCCN and Pt/C under a sine wave of 5.0 mV amplitude in the frequency range of 100 kHz to 10 mHz.

Discussion

The growth mechanism of GCN is described in Fig. 1, from where it is obvious that polyaddition and polycondensation reactions together in a continuous process built the sheets of GCN that can provides the different shapes depending on the reaction medium and conditions. In chemistry point of view initially activation of melamine to heptazine or cyamelurine was done by eliminating ammonia through nitric acid treatment. The condensation reaction among heptazine or cyamelurine unites built a polymeric network that results in GCN at higher synthesis temperature. Although the melamine goes to sublimation at higher temperature but here strong covalent bonding among these reacting sub unites made the melamine stable at higher temperature and results in the formation of GCN. After activation of melamine by nitric acid results in heptazine, which goes to polymerization process and form the melon and melon sheets. The melon sheets results in the fibrous morphology if the reaction medium is polar (ethanol), thus introduction of ethanol in the reaction system results in GCNNF structure in the present study. The strong hydrogen bonding or Van der Waals forces are strongly held these sheets to construct the various morphologies of GCN. Furthermore, by changing the reaction solvent with ethylene glycol (EG) monomers instead of ethanol can construct the tubular structure of TGCN simply introducing extra carbon during polymerization process. Probably, when nitric acid breaks the electroneutrality of aromatic rings of melamine as mentioned above, the EG polymerize on the defects created by nitric acid to construct a tubular structure. The carbonization of melamine (after activation by nitric acid) by EG modifies the reaction products to build the tubular structure and stabilize the resulted tubular morphology of TGCN. Further EG also maintains the carbon contents in GCN to alleviate the phase of g-C3N4 and continuous feeding of carbon by EG during annealing results in highly stable tubular morphology of TGCN. In addition, the growth mechanism of the tubular structure is mainly based on controlled synthesis temperatures, disturbance of the electroneutrality that offers the large number of anchoring sites to EG which tends to force the melamine to build a unique tubular morphology. In fact, the movement of carbonated species from inside to outward during annealing process creates tubular structure. Usually, GCN based materials display symmetry similar to scaffolding tri-s-triazine hexagonal structure and inter grown domains exhibit graphite-like stacking in GCN. Furthermore, there are several reports that discussed about the active sites location and their catalytic mechanisms in nitrogen-doped carbon based materials but are still inconclusive might be partially due to unavailability of appropriate characterization method. However, it is well-known fact that heteroatom-doping such as nitrogen creates net positive charge by disturbing the DOS because of its higher electronegativity. Thus, these partially positive carbon atoms are the active sites in nitrogen-doped carbon materials where the reduction of oxygen occurs and can be determined by observing the adsorbed reaction products like hydroxyl groups after the catalysis process. It is believed that the pyridinic nitrogen especially located at the edges plays a critical role through larger influence on the electronic structure of the carbon atoms in its vicinity. In short, similar to nitrogen-doped CNTs/graphene, here improved catalytic activity is based on the simple electron accepting capability of nitrogen atoms from the adjacent carbon atoms which creates a net positive charge on the GCN structure that effectively attract electrons from the anode side. Further nitrogen-doping induces over all charge delocalization in GCN structure which effectively changes the chemisorption mode of O2 from end-on adsorption to a side-on adsorption, efficiently weakens the O–O bond and assists the ORR process. However, the microstructure or location of doped nitrogen atoms implies strong effect on the catalytic performance of nitrogen-doped carbon based materials such GCN, thus by developing different morphologies change location or vicinity of the nitrogen atoms e.g. twisted tubular structure of TGCN brings more nitrogen atoms at edge sides thus enhance the overall performance of TGCN than GCNNF.

In summary, we have successfully fabricated different 1D nanostructures of GCN (tubular and nanofibers) catalysts with excellent performance as electrode of ORR for fuel cells. Among these TGCN catalyst shows prominent ORR catalytic activity that is slightly lower than commercial Pt/C regarding reaction current density and onset potential. TGCN also showed high fuel crossover resistance and much better stability in comparison to the commercial Pt/C in alkaline medium. The extraordinary performance of TGCN corresponds to its unique structure and presence of higher nitrogen contents that provides larger surface area for oxygen diffusion and active sites for its reduction, respectively. Furthermore, these 1D nanostructures were simply synthesized using inexpensive melamine as a precursor through a facile template free method which gives a great promise for large scale production without further treatment to remove the template via strong acids. The morphology of the GCN can easily be tailored by making a slight change in the mentioned procedure that emphasizes the generalization of the devised synthesis method. All the aforementioned features make proposed 1D nanostructures of GCN promising and potential substitutes instead of expensive noble metal catalysts at cathodic ORR in the next generation methanol fuel cells.

Methods

Fabrication of TGCN and GCNNF

TGCN and GCNNF were synthesized according to our previously established methodologies. Typically TGCN was prepared by dissolving 1 g of melamine in 30 mL of ethylene glycol to make a saturated solution. Then 60 ml of 0.1M HNO3 was added and stirred for 10 min. Final product was washed with ethanol and dried at 60 °C for 12 h. At last, white color powder was obtained which was annealed at 450 °C for 2 h at heating rate of 10 °C/min.

Similarly for GCNNF, 1 g of melamine was dissolved in 20 mL of ethanol and addition of, 60 mL of 0.2 M HNO3 was done with 10 min stirring. The obtained product was washed with ethanol and dried at 60 °C for 12 h. Afterward the final white color powder was annealed at 400 °C for 2 h in furnace in alumina tube at heating rate of 10 °C/min.

Characterization

The structure of the as-synthesized products was characterized by x-ray diffraction (XRD Philips X’Pert Pro MPD) with standard Cu-Kα radiation source, λ = 0.15418 nm in the 2θ range of 10–80°. Fourier transforms infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy by using Nicolet Avatar-370. The morphological characterization of the product was carried out using FEI Tecnai T20 transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-4800). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out using a PHI Quantera II (ULVAC-PHI, Japan) XPS system with monochromatic Al-Kα excitation under a vacuum better than 10−7 Pa. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) analysis was done using JEM-2100F. Surface area was determined using Beishide Instrument-ST, 3H-2000PS2 through Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) equation in the relative pressure range of 0–1.

Fabrication of electrode for ORR

Rotating-disk electrode (RDE) measurements were carried out by using a CHI 760C electrochemical workstation with a three-electrode system. Working electrode consisted of glassy-carbon (GC) (diameter 5 mm), a Pt foil was used as counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl with saturated KCl solution as reference electrode. Electrode was prepared by making the suspension of active materials with carbon (in ratio of 4:1) in ethanol (1 mg mL−1) under sonication. After sonication 10 μL of this solution was incorporated on the GC RDE using a micro-syringe, followed by dropping 5 μL of Nafion solution in ethanol (0.1 wt %) as a binder for the better adhesion of catalyst to electrode. Electrolyte is consisted of O.1M KOH aqueous solution.

Calculation for Electron Transfer number

As the number of electron transfer (n) per oxygen molecules is very important to determine the efficiency of catalyst for ORR electrode. Thus, in order to calculate n per oxygen molecule for oxygen reduction at electrode we used the K-L equation given below.

Here J is current density; Jk is kinetic limiting current densities and ω is electrode rotation rate. This equation was used to measure the B from the slope of K-L plots as given below:

Here n is the number of electrons transferred per O2, F is the Faraday constant (F = 96485 Cmol−1), C0 is bulk concentration of O2, D0 is diffusion coefficient of O2 in 0.1 M KOH and υ is a kinetic viscosity. The constant 0.2 was necessary when the rotation rate is expressed in rpm. By using the values C0 = 1.2 × 10−6 mol cm−3, D0 = 1.9 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 and υ = 0.01 cm2 s−1, n was calculated.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tahir, M. et al. One Dimensional Graphitic Carbon Nitrides as Effective Metal-Free Oxygen Reduction Catalysts. Sci. Rep. 5, 12389; doi: 10.1038/srep12389 (2015).

References

Lai, X., Halpert, J. E. & Wang, D. Recent advances in micro-/nano-structured hollow spheres for energy applications: From simple to complex systems. Energy & Environmental Science 5, 5604–5618 10.1039/c1ee02426d (2012).

Tahir, M. et al. Tubular graphitic-C3N4: a prospective material for energy storage and green photocatalysis. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 1, 13949–13955 10.1039/c3ta13291a (2013).

Tahir, M. et al. Multifunctional g-C3N4 Nanofibers: A Template-Free Fabrication and Enhanced Optical, Electrochemical and Photocatalyst Properties. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 6, 1258–1265 10.1021/am405076b (2014).

Mahmood, N., Zhang, C. & Hou, Y. Nickel Sulfide/Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Composites: Phase-Controlled Synthesis and High Performance Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. Small 9, 1321–1328 10.1002/smll.201203032 (2013).

Mahmood, N., Zhang, C., Jiang, J., Liu, F. & Hou, Y. Multifunctional Co3S4/Graphene Composites for Lithium Ion Batteries and Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Chemistry – A European Journal 19, 5183–5190 10.1002/chem.201204549 (2013).

Mahmood, N., Zhang, C., Liu, F., Zhu, J. & Hou, Y. Hybrid of Co3Sn2@Co Nanoparticles and Nitrogen-Doped Graphene as a Lithium Ion Battery Anode. ACS Nano 7, 10307–10318 10.1021/nn4047138 (2013).

Morozan, A., Jousselme, B. & Palacin, S. Low-platinum and platinum-free catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction at fuel cell cathodes. Energy & Environmental Science 4, 1238–1254 10.1039/c0ee00601g (2011).

Zhang, C., Mahmood, N., Yin, H., Liu, F. & Hou, Y. Synthesis of Phosphorus-Doped Graphene and its Multifunctional Applications for Oxygen Reduction Reaction and Lithium Ion Batteries. Advanced Materials 25, 4932–4937 10.1002/adma.201301870 (2013).

Liang, J. et al. Facile Oxygen Reduction on a Three-Dimensionally Ordered Macroporous Graphitic C3N4/Carbon Composite Electrocatalyst. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 51, 3892–3896 10.1002/anie.201107981 (2012).

Lefèvre, M., Proietti, E., Jaouen, F. & Dodelet, J.-P. Iron-Based Catalysts with Improved Oxygen Reduction Activity in Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. Science 324, 71–74 10.1126/science.1170051 (2009).

Wu, G., More, K. L., Johnston, C. M. & Zelenay, P. High-Performance Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Derived from Polyaniline, Iron and Cobalt. Science 332, 443–447 10.1126/science.1200832 (2011).

Zheng, Y. et al. Nanoporous Graphitic-C3N4@Carbon Metal-Free Electrocatalysts for Highly Efficient Oxygen Reduction. Journal of the American Chemical Society 133, 20116–20119 doi:10.1021/ja209206c (2011).

Yang, S., Feng, X., Wang, X. & Müllen, K. Graphene-Based Carbon Nitride Nanosheets as Efficient Metal-Free Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reactions. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 50, 5339–5343 10.1002/anie.201100170 (2011).

Liu, Q. & Zhang, J. Graphene Supported Co-g-C3N4 as a Novel Metal–Macrocyclic Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Fuel Cells. Langmuir 29, 3821–3828 10.1021/la400003h (2013).

Liu, G. et al. Unique Electronic Structure Induced High Photoreactivity of Sulfur-Doped Graphitic C3N4. Journal of the American Chemical Society 132, 11642–11648 10.1021/ja103798k (2010).

Yu, D., Zhang, Q. & Dai, L. Highly Efficient Metal-Free Growth of Nitrogen-Doped Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Plasma-Etched Substrates for Oxygen Reduction. Journal of the American Chemical Society 132, 15127–15129 10.1021/ja105617z (2010).

Qu, L., Liu, Y., Baek, J.-B. & Dai, L. Nitrogen-Doped Graphene as Efficient Metal-Free Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction in Fuel Cells. ACS Nano 4, 1321–1326 10.1021/nn901850u (2010).

Liu, C., Jing, L., He, L., Luan, Y. & Li, C. Phosphate-modified graphitic C3N4 as efficient photocatalyst for degrading colorless pollutants by promoting O2 adsorption. Chemical Communications 50, 1999–2001 10.1039/c3cc47398h (2014).

Liu, R., Wu, D., Feng, X. & Müllen, K. Nitrogen-Doped Ordered Mesoporous Graphitic Arrays with High Electrocatalytic Activity for Oxygen Reduction. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 49, 2565–2569 10.1002/anie.200907289 (2010).

Yang, W., Fellinger, T.-P. & Antonietti, M. Efficient Metal-Free Oxygen Reduction in Alkaline Medium on High-Surface-Area Mesoporous Nitrogen-Doped Carbons Made from Ionic Liquids and Nucleobases. Journal of the American Chemical Society 133, 206–209 10.1021/ja108039j (2011).

Yu, D., Xue, Y. & Dai, L. Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanotube Arrays Co-doped with Phosphorus and Nitrogen as Efficient Metal-Free Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 3, 2863–2870 10.1021/jz3011833 (2012).

Zheng, Y., Jiao, Y., Jaroniec, M., Jin, Y. & Qiao, S. Z. Nanostructured Metal-Free Electrochemical Catalysts for Highly Efficient Oxygen Reduction. Small 8, 3550–3566 10.1002/smll.201200861 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat Mater 8, 76–80 http://www.nature.com/nmat/journal/v8/n1/suppinfo/nmat2317_S1.html (2009).

Tahir, M. et al. Large scale production of novel g-C3N4 micro strings with high surface area and versatile photodegradation ability. CrystEngComm 16, 1825–1830 10.1039/c3ce42135j (2014).

Kwon, K., Sa, Y. J., Cheon, J. Y. & Joo, S. H. Ordered Mesoporous Carbon Nitrides with Graphitic Frameworks as Metal-Free, Highly Durable, Methanol-Tolerant Oxygen Reduction Catalysts in an Acidic Medium. Langmuir 28, 991–996 10.1021/la204130e (2012).

Tian, J. et al. Three-Dimensional Porous Supramolecular Architecture from Ultrathin g-C3N4 Nanosheets and Reduced Graphene Oxide: Solution Self-Assembly Construction and Application as a Highly Efficient Metal-Free Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 6, 1011–1017 10.1021/am404536w (2014).

Lv, Q. et al. Formation of crystalline carbon nitride powder by a mild solvothermal method. Journal of Materials Chemistry 13, 1241–1243 10.1039/b303210h (2003).

Cao, C.-B., Lv, Q. & Zhu, H.-S. Carbon nitride prepared by solvothermal method. Diamond and Related Materials 12, 1070–1074 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0925-9635(02)00309-6 (2003).

Zhang, C., Hao, R., Liao, H. & Hou, Y. Synthesis of amino-functionalized graphene as metal-free catalyst and exploration of the roles of various nitrogen states in oxygen reduction reaction. Nano Energy 2, 88–97 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.07.021 (2013).

Huang, H., Yang, S., Vajtai, R., Wang, X. & Ajayan, P. M. Pt-Decorated 3D Architectures Built from Graphene and Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets as Efficient Methanol Oxidation Catalysts. Advanced Materials 26, 5160–5165 10.1002/adma.201401877 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Work in Beijing Institute of Technology was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (23171023, 50972017) and the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20101101110026); Work at Peking University was supported by the NSFC-RGC Joint Research Scheme (51361165201), NSFC (51125001, 51172005), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2122022), Aerostatic Science Foundation (2010ZF71003) and Doctoral Program of the Ministry of Education of China (20120001110078). Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University through Prolific Research Group Project no: PRG-1436-25.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. and N.M. designed the experiment and carried out synthesis of materials and performed all the characteristic and properties, they also wrote the manuscript. C.B.C. and Y.H. provided guidance in experiment and in writing manuscript. J.Z., A.M., F.K.B., S.R., I.A., M.T., F.I. and I.S., all authors reviewed the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tahir, M., Mahmood, N., Zhu, J. et al. One Dimensional Graphitic Carbon Nitrides as Effective Metal-Free Oxygen Reduction Catalysts. Sci Rep 5, 12389 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12389

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12389

This article is cited by

-

Solvent-free coupling of aldehyde, alkyne, and amine over a versatile catalyst: Ag-functionalized mesoporous S, P-doped g-C3N4

Research on Chemical Intermediates (2021)

-

Atypical BiOCl/Bi2S3 hetero-structures exhibiting remarkable photo-catalyst response

Science China Materials (2018)

-

Self-template synthesis of biomass-derived 3D hierarchical N-doped porous carbon for simultaneous determination of dihydroxybenzene isomers

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Novel osmotin inhibits SREBP2 via the AdipoR1/AMPK/SIRT1 pathway to improve Alzheimer’s disease neuropathological deficits

Molecular Psychiatry (2017)

-

Facile synthesis of sewage sludge-derived in-situ multi-doped nanoporous carbon material for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.