Abstract

Hamiltonian engineering is an important approach for quantum information processing, when appropriate materials do not exist in nature or are unstable. So far there is no stable material for the Kitaev spin Hamiltonian with anisotropic interactions on a honeycomb lattice, which plays a crucial role in the realization of both Abelian and non-Abelian anyons. Here, we show two methods to dynamically realize the Kitaev spin Hamiltonian from the conventional Heisenberg spin Hamiltonian using pulse-control techniques based on the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff (BCH) formula. In the first method, the Heisenberg interaction is changed into Ising interactions in the first process of the pulse sequence. In the next process of the first method, we transform them to a desirable anisotropic Kitaev spin Hamiltonian. In the second more efficient method, we show that if we carefully design two-dimensional pulses that vary depending on the qubit location, we can obtain the desired Hamiltonian in only one step of applying the BCH formula. As an example, we apply our methods to spin qubits based on quantum dots, in which the effects of both the spin-orbit interaction and the hyperfine interaction are estimated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological quantum computation has attracted considerable interest due to its robustness to local perturbations1. Anyons, which obey different statistics from bosons and fermions, are also of fundamental interest in physics2. Kitaev3 provided an exactly-solvable model of a spin-1/2 system on a honeycomb lattice with potential links to topological quantum computation, for both Abelian and non-Abelian anyons. The Kitaev Hamiltonian is given by an anisotropic spin model on a 2D honeycomb lattice

where  ,

,  and

and  are the Pauli spin operators and the interaction type (

are the Pauli spin operators and the interaction type ( ,

,  and

and  links) depends on the direction of the bond between the two sites (Fig. 1). The model in Eq. (1) can be mapped to free Majorana fermions coupled to a

links) depends on the direction of the bond between the two sites (Fig. 1). The model in Eq. (1) can be mapped to free Majorana fermions coupled to a  gauge field and has two types of interesting ground states, the so-called phase

gauge field and has two types of interesting ground states, the so-called phase  and phase

and phase  , depending on the relative magnitude of

, depending on the relative magnitude of  ,

,  and

and  . The region

. The region  , where

, where  (

( = 1,2,3) refers to

= 1,2,3) refers to  ,

, ,

, , is the gapless

, is the gapless  phase in which non-Abelian anyons appear and the other region is the gapped phase

phase in which non-Abelian anyons appear and the other region is the gapped phase  , where Abelian anyon statistics is expected. In the

, where Abelian anyon statistics is expected. In the  phase, an additional external magnetic field opens an energy gap. This Kitaev model has opened a new possibility of realizing anyon based on spin systems. However, it is not easy to find materials that have such anisotropic spin-spin interactions.

phase, an additional external magnetic field opens an energy gap. This Kitaev model has opened a new possibility of realizing anyon based on spin systems. However, it is not easy to find materials that have such anisotropic spin-spin interactions.

Even if we can find a possible material for realizing a desired Hamiltonian, we have to integrate and fabricate it by attaching many electrodes and probes to confirm whether it is sufficiently controllable4,5. Regarding artificial realizations of the Kitaev Hamiltonian, theoretical proposals have been made using optical lattices6,7 and superconducting qubits8. In Ref. [You]=>[8], You et al. used different qubit-qubit interactions depending on the coupling direction. Here, we consider how to generate the Kitaev Hamiltonian starting from the Heisenberg Hamiltonian.

The Heisenberg Hamiltonian describes two-body interactions in many magnetic materials and artificial systems such as cold atoms6, semiconductor quantum dot (QD) systems9,10,11,12,13,14,15, donor systems16,17,18,19 and nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers20,21,22. The Heisenberg Hamiltonian is given by

where only the nearest-neighbor interactions are assumed here. The problem to be solved is to find a way to derive the Kitaev Hamiltonian Eq. (1) from the Heisenberg Hamiltonian of Eq. (2). The difficulty is to derive the anisotropic interaction of the Kitaev Hamiltonian from the uniform interaction of the Heisenberg Hamiltonian. For example, although the tunneling couplings  of the spin qubits based on QDs can be varied uniformly by attaching gate electrodes, we cannot control the anisotropy of the interactions by only changing the strength of the tunneling couplings23. The purpose of this paper is to propose two methods to dynamically derive the Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Heisenberg Hamiltonian.

of the spin qubits based on QDs can be varied uniformly by attaching gate electrodes, we cannot control the anisotropy of the interactions by only changing the strength of the tunneling couplings23. The purpose of this paper is to propose two methods to dynamically derive the Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Heisenberg Hamiltonian.

The two methods provided here are based on pulse-control technique using the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff (BCH) formula between the Heisenberg Hamiltonian and the transformed Hamiltonians. These transformed Hamiltonians are produced by applying appropriate pulse sequences to the Heisenberg Hamiltonian. The BCH formula is useful for creating desirable effective Hamiltonians24. However, because unwanted terms are generated by the BCH formula, it is desirable to reduce the number of times the BCH formula is applied to different transformed Hamiltonian.

In the first method provided here, which we call the direct method, the Heisenberg interaction is changed into  ,

,  and

and  Ising couplings, by using the corresponding transformed Hamiltonians in the first process. In the second process of the direct method, three other transformed Hamiltonians are used to change the Ising couplings into the desired

Ising couplings, by using the corresponding transformed Hamiltonians in the first process. In the second process of the direct method, three other transformed Hamiltonians are used to change the Ising couplings into the desired  ,

,  and

and  -links. When we count the number of the steps required to obtain the different transformed Hamiltonians, the direct method requires six steps to obtain the Kitaev spin Hamiltonian. In the second method, which we call the efficient method, we show that if we carefully design two-dimensional (2D) pulses that vary depending on the qubit location, we can obtain the desired Hamiltonian in only one step where one transformed Hamiltonian is used.

-links. When we count the number of the steps required to obtain the different transformed Hamiltonians, the direct method requires six steps to obtain the Kitaev spin Hamiltonian. In the second method, which we call the efficient method, we show that if we carefully design two-dimensional (2D) pulses that vary depending on the qubit location, we can obtain the desired Hamiltonian in only one step where one transformed Hamiltonian is used.

Because the engineered Hamiltonian is effective only for a finite time interval, the dynamical approach requires a refresh process in which the same pulse sequence for generating the Kitaev Hamiltonian is carried out. The idea of repeating the production process is very common in conventional digital computers, such as dynamic random access memory (DRAM), which essentially is a big capacitor and the amount of electric charge is lost over time25. We consider the refresh overhead of the dynamical methods and compare the two proposed methods quantitatively.

As a concrete example of the application of our methods, we consider the spin qubits based on QDs. In general, QDs have both spin-orbit interactions26,27,28 and hyperfine interactions29,30,31. Therefore, we will discuss the effects of these interactions, other than the unwanted terms derived from the BCH formula, on the topological Hamiltonian, focusing on the gapped phase (phase  ).

).

Results

Dynamical creation of the Kitaev spin Hamiltonian from the Heisenberg model

Now, we explain how to derive Eq. (1) from the Heisenberg Hamiltonian Eq. (2). The “creation” of Eq. (1) is carried out by combining  with a transformed Hamiltonian

with a transformed Hamiltonian  , which is produced by applying a customized pulse sequence to

, which is produced by applying a customized pulse sequence to  , like in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), by a repeated application of the BCH formula. Concretely, the target Hamiltonian

, like in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), by a repeated application of the BCH formula. Concretely, the target Hamiltonian  is approximately obtained by

is approximately obtained by  , such as

, such as

when  . In the exponent of the right side of this equations, the terms

. In the exponent of the right side of this equations, the terms  beyond the first term are the unwanted ones. The transformed Hamiltonian

beyond the first term are the unwanted ones. The transformed Hamiltonian  is produced by using rotations of the Pauli operators,

is produced by using rotations of the Pauli operators,  ,

,  and

and  . These rotations are obtained by the operations given by

. These rotations are obtained by the operations given by

and  . We have similar equations for the rotations of the

. We have similar equations for the rotations of the  and

and  operators. In the following, we show that the first method (direct method) uses Eq. (3) six times, but the second method (efficient method) uses it only once.

operators. In the following, we show that the first method (direct method) uses Eq. (3) six times, but the second method (efficient method) uses it only once.

Direct method

The direct way to convert Eq. (2) to Eq. (1) requires six steps, as shown in Fig. 2. The first process is to create the three Ising Hamiltonians,  ,

,  ,

,  , from Eq. ((2)) ==> (2) as shown in Figs. 2(a,c,e). The generated Ising Hamiltonians are described by

, from Eq. ((2)) ==> (2) as shown in Figs. 2(a,c,e). The generated Ising Hamiltonians are described by

Direct method to dynamically produce a Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Heisenberg model.

The symbols  ,

,  and

and  in the lattice sites show the application of

in the lattice sites show the application of  -pulses around

-pulses around  ,

,  and

and  , respectively. The bonds with dotted lines indicate that there is no interaction between the connected sites. (a) Pulse mapping of

, respectively. The bonds with dotted lines indicate that there is no interaction between the connected sites. (a) Pulse mapping of  to create the Ising Hamiltonian,

to create the Ising Hamiltonian,  in

in  . (b) Pulse mapping to select only the

. (b) Pulse mapping to select only the  -link of the Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Ising Hamiltonian of (a). (c) and (e) express pulse distributions for generating

-link of the Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Ising Hamiltonian of (a). (c) and (e) express pulse distributions for generating  and

and  , respectively. (d) and (f) show pulse pattern to select only the

, respectively. (d) and (f) show pulse pattern to select only the  and

and  links, respectively.

links, respectively.

where  (

( ) is a rotated Hamiltonian, in which

) is a rotated Hamiltonian, in which  shows

shows  -pulse rotations around the

-pulse rotations around the  -axes on the lattice sites of Figs. 2(a,c,e). The next process is to eliminate unnecessary Ising interactions, such as

-axes on the lattice sites of Figs. 2(a,c,e). The next process is to eliminate unnecessary Ising interactions, such as

where  is obtained by applying a

is obtained by applying a  -pulse operation

-pulse operation  depending on the links in Figs. 2(b,d,f).

depending on the links in Figs. 2(b,d,f).

Thus, the Kitaev Hamiltonian is dynamically obtained by

(See also Sec. I of the supplementary information). Note that parts of the Kitaev Hamiltonian do not commute,  ,

,  . Therefore, the unwanted terms emerge even in the process Eq.((7)) ==> (7) of combining the

. Therefore, the unwanted terms emerge even in the process Eq.((7)) ==> (7) of combining the  ,

,  and

and  Ising couplings. In the following, we show a better method in which the

Ising couplings. In the following, we show a better method in which the  ,

,  and

and  Ising couplings are generated in a single process.

Ising couplings are generated in a single process.

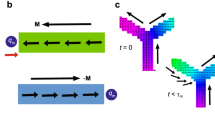

Efficient method.

Because the coherence time is limited, a generation method using less time can be regarded as more efficient. When we apply rotation pulses more compactly, the Kitaev Hamiltonian  is produced more efficiently from

is produced more efficiently from  . Fig. 3 shows the distributions of the rotation pulses

. Fig. 3 shows the distributions of the rotation pulses  by which the BCH formula is used only once, such that

by which the BCH formula is used only once, such that

Efficient method to dynamically produce a Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Heisenberg model.

The efficient pulse distribution  for

for  , in order to dynamically produce a Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Heisenberg model via one step. The

, in order to dynamically produce a Kitaev Hamiltonian from the Heisenberg model via one step. The  ,

,  and

and  on the lattice sites show the application of

on the lattice sites show the application of  -pulses around

-pulses around  ,

,  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

with  . The

. The  -link of the colored honeycomb is produced by applying a rotation around the

-link of the colored honeycomb is produced by applying a rotation around the  -axis and that around the

-axis and that around the  -axis on both sides of the link. Similarly, the

-axis on both sides of the link. Similarly, the  (

( )-link is produced by a rotation around the

)-link is produced by a rotation around the  (

( )-axis and around the

)-axis and around the  (

( )-axis on both sides of the link (see also Sec. II of the supplementary information).

)-axis on both sides of the link (see also Sec. II of the supplementary information).

Refresh overhead

If  denotes the time of a single-qubit rotation, it takes

denotes the time of a single-qubit rotation, it takes  and

and  to produce the rotations

to produce the rotations  and

and  , respectively. Similar to the conventional DRAM, here we define the refresh overhead as the effectiveness of the refresh of the quantum state:

, respectively. Similar to the conventional DRAM, here we define the refresh overhead as the effectiveness of the refresh of the quantum state:

The refresh overhead of the efficient method presented above is

and that of the direct method shown previously is

for  . Thus, the efficient method is three times more efficient than the direct method.

. Thus, the efficient method is three times more efficient than the direct method.

Fidelity

Let us numerically estimate the improvement of the efficient method by calculating a time-dependent gate fidelity32. The time-dependent gate fidelity is defined by

where  denotes the evolution operator of the pulsed system. The gate fidelity shows how well the transformed Hamiltonian evolves compared with

denotes the evolution operator of the pulsed system. The gate fidelity shows how well the transformed Hamiltonian evolves compared with  . For the direct method,

. For the direct method,  is given by

is given by

with  , for

, for  and

and  . Note that

. Note that  and

and  transform

transform  into the rotated ones shown in Figs. 2(a,c,e) and (b,d,f), respectively. In contrast, for the efficient pulse arrangement,

into the rotated ones shown in Figs. 2(a,c,e) and (b,d,f), respectively. In contrast, for the efficient pulse arrangement,  is expressed by

is expressed by

Thus, the evolution operator Eq. (14) of the efficient method is much simpler than that of the direct method Eq. (13). Here we consider the general case in which the spin-orbit interaction and the hyperfine interaction are added to the Heisenberg Hamiltonian Eq. (2), assuming the spin qubits based on QDs. The spin-orbit interaction is expressed by

where  and the magnitudes of the spin-orbit vectors

and the magnitudes of the spin-orbit vectors  and

and  are 10−2 smaller28 than

are 10−2 smaller28 than  . The hyperfine interaction is given by the fluctuation of the field30, such as

. The hyperfine interaction is given by the fluctuation of the field30, such as  . We treat the hyperfine field as a static quantity because the evolution of the hyperfine field is ~10

. We treat the hyperfine field as a static quantity because the evolution of the hyperfine field is ~10  s and much slower than the time-scale of11 the pulse-control ~100 ns. The total Hamiltonian of this system is

s and much slower than the time-scale of11 the pulse-control ~100 ns. The total Hamiltonian of this system is  . The Chebyshev expansion method is used for calculating the time-dependent behavior until its 6th-order term33. We have considered several parameter regions such as (i)

. The Chebyshev expansion method is used for calculating the time-dependent behavior until its 6th-order term33. We have considered several parameter regions such as (i)  ,

,  and

and  , (ii)

, (ii)  ,

,  and

and  and (iii)

and (iii)  ,

,  and

and  (

( ). Figure 4 shows for the numerical results for

). Figure 4 shows for the numerical results for  qubits (two honeycomb lattices) for Jx = Jy = 0.3 Jz, dα = 0.1 and δhα = 0.1. In various parameter regions, the overlap with the Kitaev Hamiltonian is excellent when using the pulse-controlled method. We also find that iterating the same BCH formula34 greatly increases the gate fidelity, which is similar to the bang-bang control35.

qubits (two honeycomb lattices) for Jx = Jy = 0.3 Jz, dα = 0.1 and δhα = 0.1. In various parameter regions, the overlap with the Kitaev Hamiltonian is excellent when using the pulse-controlled method. We also find that iterating the same BCH formula34 greatly increases the gate fidelity, which is similar to the bang-bang control35.

Numerically-calculated gate fidelity.

Here “dir” corresponds to the  method (Fig. 2) and “eff” corresponds to the efficient method (Fig. 3), respectively. “BCH–

method (Fig. 2) and “eff” corresponds to the efficient method (Fig. 3), respectively. “BCH– ” means that the BCH formula is applied

” means that the BCH formula is applied  times. Repeatedly applying the BCH formula corresponds to a refresh process, which improves the gate fidelity. Jx = Jy = 0.30 Jz, dα = 0.1 and δhα = 0.1.

times. Repeatedly applying the BCH formula corresponds to a refresh process, which improves the gate fidelity. Jx = Jy = 0.30 Jz, dα = 0.1 and δhα = 0.1.

Time-dependent Eigenvalue

In order to directly see the effects of the unwanted terms, spin-orbit terms and hyperfine terms, we calculate the time-dependent eigenvalues of the effective Hamiltonian  , of the efficient method. Because of limited computational resources, we show the numerical results for

, of the efficient method. Because of limited computational resources, we show the numerical results for  and

and  . We find that an energy gap opens up in the

. We find that an energy gap opens up in the  region. The energy gap becomes narrow for

region. The energy gap becomes narrow for  , compared for

, compared for  , because of finite-size effects. When we compare Fig. 5(d) with Fig. 5(c), we find that the spin-orbit terms and the hyperfine terms decrease the energy gap for large-

, because of finite-size effects. When we compare Fig. 5(d) with Fig. 5(c), we find that the spin-orbit terms and the hyperfine terms decrease the energy gap for large- systems. In many systems, we cannot neglect additional interactions other than the Heisenberg interactions. Here, the spin-orbit and the hyperfine interactions represent such additional interactions. The results of Figs. 5(b,d) show that, although the energy gap between the ground state and the excited state of Kitaev Hamiltonian is modified by those interactions, the energy gap is detectable as long as the effect of the additional interactions is small.

systems. In many systems, we cannot neglect additional interactions other than the Heisenberg interactions. Here, the spin-orbit and the hyperfine interactions represent such additional interactions. The results of Figs. 5(b,d) show that, although the energy gap between the ground state and the excited state of Kitaev Hamiltonian is modified by those interactions, the energy gap is detectable as long as the effect of the additional interactions is small.

Toric code Hamiltonian

The unperturbed Hamiltonian of the  phase is given by

phase is given by  , whose ground state is a degenerate dimer state. Then,

, whose ground state is a degenerate dimer state. Then,  acts as a perturbation and generates the toric code Hamiltonian3,36. Comparing the unwanted terms

acts as a perturbation and generates the toric code Hamiltonian3,36. Comparing the unwanted terms  , the spin-orbit terms and the hyperfine terms, with the effective toric code Hamiltonian in Ref.3 implies the constraints

, the spin-orbit terms and the hyperfine terms, with the effective toric code Hamiltonian in Ref.3 implies the constraints

where  and

and  (see Sec. VI of the supplementary information). From these estimates, in order to realize the topological quantum computation, both the spin-orbit and the hyperfine interactions should be as small as possible.

(see Sec. VI of the supplementary information). From these estimates, in order to realize the topological quantum computation, both the spin-orbit and the hyperfine interactions should be as small as possible.

Effects of errors in rotations.

Let us consider the effects of errors in rotations. In Eq. (4), when there is a pulse error  in

in  . These rotations are carried out by the operations:

. These rotations are carried out by the operations:

We have similar equations for the  and

and  components. When we apply these equations with

components. When we apply these equations with  to the Heisenberg Hamiltonian

to the Heisenberg Hamiltonian  , we have

, we have

Thus, the unwanted terms from the pulse errors are counted in order of  . It is considered that these pulse errors can be reduced by using the conventional composite pulse method developed37,38 in NMR.

. It is considered that these pulse errors can be reduced by using the conventional composite pulse method developed37,38 in NMR.

Discussion

Because our methods use many single-qubit rotations, a short  is important such that all the operations can be carried out during the coherence time of the system. For example, when

is important such that all the operations can be carried out during the coherence time of the system. For example, when  1 ns, the efficient method requires a time of

1 ns, the efficient method requires a time of  4 ns and the direct method requires a time of 24 ns. In this case, the coherence time should be longer than at least 24 ns for the realization of both methods. As an example, we consider the spin-qubit based on QDs, in which the coherence time is estimated by the dephasing time. When the dephasing time is

4 ns and the direct method requires a time of 24 ns. In this case, the coherence time should be longer than at least 24 ns for the realization of both methods. As an example, we consider the spin-qubit based on QDs, in which the coherence time is estimated by the dephasing time. When the dephasing time is  10 ns as in Ref. [11], only the efficient method is applicable. When the dephasing time is

10 ns as in Ref. [11], only the efficient method is applicable. When the dephasing time is  100 ns as in Ref. [12], both methods can be applied.

100 ns as in Ref. [12], both methods can be applied.

Next, let us discuss a measurement process of topological quantum computation in spin qubits. The toric code and the surface code are based on the stabilizer formalism39,40 where desired quantum states are obtained by stabilizer measurements. These measurements can be carried out using conventional spin-qubit operations by manipulating the Heisenberg model with appropriate magnetic fields. However, because the desired states are not always eigenstates of the Heisenberg Hamiltonian, the desired states are not preserved41. Thus, our proposed methods, which can preserve the desired states of the topological quantum computation, are important after the measurement. Let us estimate the measurement time in more details. In each measurement process of the surface code, four CNOT gates and two Hadamard gates are required39. When each CNOT gate consists10 of two  s and each

s and each  requires a time

requires a time  , where

, where  is a Heisenberg coupling strength for the measurement, one stabilizer measurement cycle approximately requires a time

is a Heisenberg coupling strength for the measurement, one stabilizer measurement cycle approximately requires a time  . Because a short measurement time and a long coherence-preserving time

. Because a short measurement time and a long coherence-preserving time  ) are preferable, it is desirable for the coupling strength between qubits to be changeable and therefore

) are preferable, it is desirable for the coupling strength between qubits to be changeable and therefore  is desirable. The coupling

is desirable. The coupling  of the Heisenberg interaction can be changed by the gate voltage in spin-qubit systems based on QDs.11,12,13,14. As an example,

of the Heisenberg interaction can be changed by the gate voltage in spin-qubit systems based on QDs.11,12,13,14. As an example,  -

- eV is obtained, when the voltage difference between two GaAs QDs is less than 10 mV11 and we can choose

eV is obtained, when the voltage difference between two GaAs QDs is less than 10 mV11 and we can choose  eV and

eV and  eV. When

eV. When  eV (= 0.0116 K), the period

eV (= 0.0116 K), the period  corresponds to the refresh time

corresponds to the refresh time  ns.

ns.

Because the fabrication process is not easy in qubits of any type, the variation of the coupling constant  cannot be avoided in experiments. In this paper, we have shown the effect of the spin-orbit and the hyperfine interactions as examples of the unwanted terms of our methods. Thus, as long as the variation of

cannot be avoided in experiments. In this paper, we have shown the effect of the spin-orbit and the hyperfine interactions as examples of the unwanted terms of our methods. Thus, as long as the variation of  is small, it can be included as a small perturbation without significant effects on the generation of the Kitaev Hamiltonian and the toric code Hamiltonian.

is small, it can be included as a small perturbation without significant effects on the generation of the Kitaev Hamiltonian and the toric code Hamiltonian.

In summary, we proposed two methods to dynamically generate a Kitaev spin Hamiltonian on a honeycomb lattice from the Heisenberg spin Hamiltonian by using a dynamical approach. We also considered the effects of the unwanted terms of the BCH, the spin-orbit interaction and the hyperfine interaction, for spin qubits based on QDs. We clarified that, if these terms are sufficiently small, a dynamic topological quantum computation is available by periodically reproducing the topological Hamiltonian.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tanamoto, T. et al. Dynamic creation of a topologically-ordered Hamiltonian using spin-pulse control in the Heisenberg model. Sci. Rep. 5, 10076; doi: 10.1038/srep10076 (2015).

Change history

12 January 2016

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Wen, X. G. Quantum Field Theory of Many-body Systems (Oxford University Press: New York, 2004).

Wilczek, F. Fractional Statistics and Anyon Superconductivity (World Scientific: Singapore, 1990).

Kitaev, A. Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Annals of Physics 321, 2–111 (2006).

Manousakis, E. A quantum-dot array as model for copper-oxide superconductors: A dedicated quantum simulator for the many-fermion problem, J. Low Temp. Phys. 126, 1501–1513 (2002).

Georgescu, I. M., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Quantum simulation, Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014).

Duan, L. M., Demler, E. & Lukin, M. D. Controlling Spin Exchange Interactions of Ultracold Atoms in Optical Lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 090402 (2003).

Aguado, M., Brennen, G. K., Verstraete, F., & Cirac, J. I. Creation, Manipulation and Detection of Abelian and Non-Abelian Anyons in Optical Lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 260501 (2008).

You, J. Q., Shi, X. F., Hu, X. & Nori, F. Quantum emulation of a spin system with topologically protected ground states using superconducting quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. B. 81, 014505 (2010).

Loss, D. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A. 57, 120 (1998).

Burkard, G., Loss, D., DiVincenzo, D. P. & Smolin, J. A. Physical optimization of quantum error correction circuits. Phys. Rev. B. 60, 11404 (1999).

Petta, J. R. et al. Coherent Manipulation of Coupled Electron Spins in Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Science 309, 2180–2184 (2005).

Maune, B. M. et al. Coherent singlet-triplet oscillations in a silicon-based double quantum dot. Nature 481, 344–347 (2012).

Burkard, G., Seelig, G., & Loss, D. Spin interactions and switching in vertically tunnel-coupled quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B. 62, 2581 (2000).

Hu, X., & Das Sarma, S. Hilbert-space structure of a solid-state quantum computer: Two-electron states of a double-quantum-dot artificial molecule. Phys. Rev. A. 61, 062301 (2000).

Ono, K., Austing, D. G., Tokura, Y. & Tarucha S. Current rectification by Pauli exclusion in a weakly coupled double dot system. Science 297, 1313–1317 (2002).

Kane, B. E. A silicon-based nuclear spin quantum computer. Nature 393, 133–137 (1998).

Salfi, J. et al. Spatially resolving valley quantum interference of a donor in silicon, Nature Mater. 13, 605–610 (2014).

Hamid, E. et al. Electron-tunneling operation of single-donor-atom transistors at elevated temperatures. Phys. Rev. B. 87, 085420 (2013).

Ono, K., Tanamoto, T., & Oguro, T. Pseudosymmetric bias and correct estimation of Coulomb/confinement energy for unintentional quantum dot in channel of metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 183107 (2013).

Jelezko, F., Gaebel, T., Popa, I., Gruber, A. & Wrachtrup, J. Observation of Coherent Oscillations in a Single Electron Spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 076401 (2004).

Yao, N. Y., Jiang, L., Gorshkov, A. V., Gong, Z.-X., Zhai, A. Robust Quantum State Transfer in Random Unpolarized Spin Chains. Duan, L.-M., & Lukin, M.D., Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 040505 (2011).

Ping, Y., Lovett, B. W. Benjamin, S. C., & Gauger, E.M. Practicality of Spin Chain Wiring in Diamond Quantum Technologies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 100503 (2013).

Tanamoto, T., Liu, Y. X., Hu, X. & Nori, F. Efficient Quantum Circuits for One-Way Quantum Computing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 100501 (2009).

Tong, Q. J., An, J. H., Gong, J., Luo, H. G. & Oh, C. H. Phys. Rev. B 87, 201109(R) (2013).

Keeth, B. & Baker, R. J. DRAM Circuit Design: A Tutorial (John Wiley & Sons, 2001).

Khaetskii, A. V. & Nazarov, Y. V. Spin relaxation in semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B. 61,12 639 (2000).

Golovach, V. N., Khaetskii, A. & Loss D. Phonon-Induced Decay of the Electron Spin in Quantum Dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93.016601 (2004).

Baruffa, F., Stano, P. & Fabian, J. Theory of Anisotropic Exchange in Laterally Coupled Quantum Dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 126401 (2010).

Yao, W., Liu, R. B. & Sham, L. J. Theory of electron spin decoherence by interacting nuclear spins in a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 74,195301 (2006).

Cywinski, L. Dephasing of electron spin qubits due to their interaction with nuclei in quantum dots. Acta Phys. Pol. A 119, 576–575 (2011).

Cywinski, L., Witzel W. M. & Das Sarma, S. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 057601 (2009).

Becker, D., Tanamoto, T., Hutter, A., Pedrocchi, F. L. & Loss, D. Dynamic generation of topologically protected self-correcting quantum memory. Phys. Rev. A 87, 042340 (2013).

Kosloff, R. & Tal-Ezer, H. A direct relaxation method for calculating eigenfunctions and eigenvalues of the Schroedinger equation on a grid. Chem. Phys. Lett. 127, 223–230 (1986).

Tanamoto, T. Implementation of standard quantum error-correction codes for solid-state qubits. Phys. Rev. A. 88, 062334 (2013).

Viola, L. & Lloyd, S. Dynamical suppression of decoherence in two-state quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 58, 2733 (1998).

Kells, G. et al. Topological Degeneracy and Vortex Manipulation in Kitaev’s Honeycomb Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 240404 (2008).

Ernst, R. R., Bodenhausen, G. & Wokaun, A. Principles of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in One and Two Dimensions (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Driven coherent oscillations of a single electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 442, 766 (2006).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J.M. & Cleland, A.N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A. 86, 032324 (2012).

Bravyi, S. B. & Kitaev, A. Quantum codes on a lattice with boundary. quant-ph/9811052.

Tanamoto, T., Stojanovic′, V. M., Bruder, C., & Becker, D. Strategy for implementing stabilizer-based codes on solid-state qubits.Phys. Rev. A 87, 052305 (2013).

Acknowledgements

TT would like to thank A. Nishiyama, K. Muraoka, S. Fujita and H. Goto for discussions. YXL is supported by the NSFC under Grant Nos. 61025022, 91321208, the National Basic Research Program of China Grant No. 2014CB921401. FN is partially supported by the RIKEN iTHES Project, MURI Center for Dynamic Magneto-Optics and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T. carried out all the calculations. All authors contributed to the discussions, the interpretation of the work and the writing of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tanamoto, T., Ono, K., Liu, Yx. et al. Dynamic creation of a topologically-ordered Hamiltonian using spin-pulse control in the Heisenberg model. Sci Rep 5, 10076 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10076

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10076

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

, for

, for  (a,b) and

(a,b) and  (c,d).

(c,d).  (a,c) use

(a,c) use  . (b,d) use

. (b,d) use  . Eigenenergies are scaled by

. Eigenenergies are scaled by  .

.