Abstract

Tropospheric ozone concentrations have increased by 60–100% in the Northern Hemisphere since the 19th century. The phytotoxic nature of ozone can impair forest productivity. In addition, ozone affects stomatal functions, by both favoring stomatal closure and impairing stomatal control. Ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness, i.e., a delay in stomatal responses to fluctuating stimuli, has the potential to change the carbon and water balance of forests. This effect has to be included in models for ozone risk assessment. Here we examine the effects of ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness on carbon assimilation and transpiration of temperate deciduous forests in the Northern Hemisphere in 2006-2009 by combining a detailed multi-layer land surface model and a global atmospheric chemistry model. An analysis of results by ozone FACE (Free-Air Controlled Exposure) experiments suggested that ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness can be incorporated into modelling based on a simple parameter (gmin, minimum stomatal conductance) which is used in the coupled photosynthesis-stomatal model. Our simulation showed that ozone can decrease water use efficiency, i.e., the ratio of net CO2 assimilation to transpiration, of temperate deciduous forests up to 20% when ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness is considered and up to only 5% when the stomatal sluggishness is neglected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropospheric ozone (O3) is recognized as a significant phytotoxic air pollutant and greenhouse gas1, formed from photochemical reactions of its precursors such as nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds2. Ozone concentrations have increased by approximately 60–100% since pre-industrial times in the Northern Hemisphere3,4,5. Ozone is considered to be one of the most important factors affecting forest health6.

Stomata, i.e., small pores on leaves, are a crucial interface for gas exchange between forests and the atmosphere. Ozone enters plants via stomata and causes a decline of photosynthetic capacity6. In addition, O3 is generally known to induce stomatal closure7, which results in reduced O3 uptake by plants and water saving due to less transpiration. In parallel, O3 exposure also causes slow or less efficient stomatal control (O3-induced stomatal sluggishness)7, which results in incomplete stomatal closure e.g. under low light conditions (i.e., leaky stomata). This may lead to further O3 uptake and water consumption. Ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness has been reported in many temperate tree species7,8,9,10,11. Existing models for O3 risk assessment in forests have included O3 effect on stomata as a decrease in stomatal conductance proportional to the O3-induced decline of photosynthesis5,12, while the effect of O3-induced stomatal sluggishness has been usually neglected. This sluggish response along with O3-impaired photosynthesis may significantly change the water and carbon balance of forests under a changing environment4. Lombardozzi et al.9 included O3-induced stomatal sluggishness in a global biosphere model where the data were from chamber experiments on tulip poplar and a constant 100 nmol mol–1 O3 concentration across the world was simulated. They suggested that O3-induced stomatal sluggishness may ameliorate the O3-induced decline of carbon assimilation and transpiration of trees9. However, the environmental conditions in the chambers (e.g., enhanced air temperature, high air ventilation) are known to change plant responses to O3 relative to actual field conditions13. Therefore, the results have to be verified based on more realistic data from technologies such as the recently developed O3-FACE (Free-Air Controlled Exposure) approach14. In this study, we used O3-FACE data and estimated O3-induced stomatal sluggishness implications for carbon assimilation and transpiration. We focused on O3-sensitive temperate deciduous forests exposed to realistic O3 concentrations in the Northern Hemisphere.

As postulated by two recent studies15,16, we considered the following new concept for modelling O3 effects on stomata: 1) stomata close in tandem with the O3-induced decline of photosynthesis and 2) stomatal response to environmental variables is impaired due to O3-induced stomatal sluggishness. We then investigated how O3 uptake changed the parameters of the photosynthesis-stomatal model (the Ball-Woodrow-Berry model17, see Methods), which is widely used in many land-surface schemes in climate models5,9. Reliable O3-FACE datasets for modelling O3-induced stomatal sluggishness along the forest growing season are currently very limited. To our knowledge, a reliable dataset for analyzing the relationship between O3-induced stomatal sluggishness and O3 uptake over the growing season is available from our previous work18, which investigated the seasonal change of stomatal conductance of Siebold’s beech (Fagus crenata) under free-air O3 exposure (O3-FACE) in Japan. Using this dataset, we derived the parameters of the Ball-Woodrow-Berry model for assessing O3-induced stomatal sluggishness. To verify our result, we analyzed literature values of stomatal conductance from another O3-FACE experiment with trees, i.e., the Aspen FACE19 and estimated the Ball-Woodrow-Berry model parameters. Although we could not analyze the relationship between O3-induced stomatal sluggishness and O3 uptake using the Aspen FACE data due to the limitation of the measurement period (only once in July), an intercomparison of the results allowed us to validate the parameters of O3-induced stomatal sluggishness. Finally, using the parameters for Siebold’s beech, the impact of O3-induced stomatal sluggishness on net CO2 assimilation and transpiration in temperate deciduous forests in the Northern Hemisphere was calculated by offline (one-way) coupling simulations of a multi-layer atmosphere-SOil-VEGetation model (SOLVEG)20,21 and Meteorological Research Institute Chemistry-Climate Model version 2 (MRI-CCM2)22,23. Three SOLVEG simulations were carried out: 1) including no O3 effect (“control run”), 2) including O3 effects on photosynthesis without O3-induced stomatal sluggishness (“no sluggishness run”) and 3) including O3 effects on photosynthesis with O3-induced stomatal sluggishness (“sluggishness run”) (see Methods). Ozone-induced changes of net CO2 assimilation, transpiration and water use efficiency (WUE), i.e., the ratio of net CO2 assimilation to transpiration, were assessed by the ratio of differences between “sluggishness run” or “no sluggishness run” and “control run”.

Results and Discussion

Our study suggests a simple way to include O3-induced stomatal sluggishness in the Ball-Woodrow-Berry model. This model has two empirical parameters (see Eq. 1 in Methods): m, slope of the linear relationship between stomatal conductance and photosynthesis; and gmin, y-intercept of this relationship. We found that gmin of Siebold’s beech increased due to an increase of cumulative O3 uptake (Fig. 1), while there was no significant relationship between m and cumulative O3 uptake (data not shown, linear regression analysis, p = 0.329). This enhanced gmin after O3 exposure (Fig. 1, S1B, S1C) was supported by the analysis of literature data from Aspen FACE (gmin was 0.034 mol m−2 s−1 in ambient air and 0.100 mol m−2 s−1 at elevated O3, Fig. S2). Ozone is generally known to cause a reduction of WUE5. An increase of gmin without change of m indicates a reduction of WUE at elevated O3 compared to ambient conditions (Fig. S1B, S1C, S2). The enhanced gmin can be considered as slowed stomatal closure to decreasing light intensity under elevated O37,11. This implies imperfect stomatal closing under low light conditions18 and impaired control on water loss7.

Changes of gmin over a range of cumulative O3 uptake (CUO) used for the “sluggishness run” and “no sluggishness run” of SOLVEG-MRI-CCM2. Data points of gmin were obtained from an analysis of measurements in June, August and October 2012 (see Fig. S1) at the O3-FACE experiment on Siebold’s beech in Japan (blue circle: ambient O3; red circle: elevated O3). Obtained gmin were fitted by a sigmoid function for “sluggishness run” (solid line): gmin = 0.03 + 0.09/[1 + exp{–0.21·(CUO – 24.7)}], R2 = 0.89. Dashed line shows no change of gmin (gmin = 0.03 mol m−2 s−1) and was used for “no sluggishness run”.

The novel parameterization of gmin shown in Fig. 1 was then applied to simulate the O3 effect on carbon and water balances in temperate deciduous forests in the Northern Hemisphere. Those forests are dominated by oak, poplar and beech species24. While oaks are usually O3 tolerant species12, we investigated the response of two species, beech and aspen, that are O3-sensitive5,12 and representative of late and early successional forests, respectively. So our simulations explored the impact of O3 on carbon and water balance in O3–sensitive temperate deciduous forests of the Northern Hemisphere. The offline coupling simulations of SOLVEG and MRI-CCM2 revealed that net CO2 assimilation declined with an increase of O3 exposure (Fig. 2a) and of canopy cumulative O3 uptake (Fig. 2b). The O3-induced decline of net CO2 assimilation at the average daytime O3 concentrations of 37.2 ± 6.2 nmol mol−1 was 6.6 ± 2.1% and 6.0 ± 1.8% in the “sluggishness run” and “no sluggishness run”, respectively (Figs. 2a, 2b) as an average of all years and grids where temperate deciduous forests occurred (Fig. S3). Therefore, O3-induced stomatal sluggishness did not ameliorate the effect of O3 on carbon assimilation of trees as suggested by Lombardozzi et al.9. Higher O3 concentrations, e.g., 44.6 ± 4.7 nmol mol−1 as an average of daytime values over China, resulted in 9.1 ± 2.0% and 8.0 ± 1.6% reductions in the “sluggishness run” and “no sluggishness run”, respectively. Such a stronger impact on carbon assimilation, when O3-induced stomatal sluggishness was included, was due to enhanced stomatal O3 uptake, which led to a further negative impact on photosynthesis.

Percent change of modelled net CO2 assimilation, transpiration and water use efficiency in temperate deciduous forests in the Northern Hemisphere in relation to daytime mean O3 concentration or cumulative canopy O3 uptake (years 2006-2009). a, net CO2 assimilation, b, transpiration and c, water use efficiency were simulated by the offline coupling simulation of SOLVEG-MRI-CCM2. Effects of O3-induced stomatal sluggishness were included (black open circles and red lines) or excluded (gray circles and gray lines). The percentage of change of each parameter was calculated relative to “control run” (no O3 effect).

The “no sluggishness run” predicted a monotonic reduction of transpiration by stomatal closure under elevated O3, in tandem with declining carbon assimilation (Fig. 2b, gray line), as reported in state-of-art global climate models5. In contrast, the “sluggishness run” showed a decrease of transpiration until 30 nmol mol−1 of O3 concentration or 37 mmol m−2 of canopy cumulative O3 uptake and then an increase with increasing O3 exposure or uptake (Fig. 2b, red line). This suggests that the tight coupling of stomatal conductance and photosynthesis at low O3 environment cannot be maintained at higher O3 pollution and results in increasing transpirational water loss due to sluggish stomata. As a result, O3–induced reduction of transpiration at the average daytime O3 concentration of 37.2 ± 6.2 nmol mol−1 was only 1.0 ± 1.4% in the “sluggishness run”, while a larger decline (3.4 ± 1.1%) was found in the “no sluggishness run” (Fig. 2b). At higher O3 concentrations, e.g., 44.6 ± 4.7 nmol mol−1 as an average of daytime values over China, the decline was 0.3 ± 1.6% and 4.3 ± 1.0% in the “sluggishness run” and “no sluggishness run”, respectively. In agreement with a meta-analytic review by Lombardozzi et al.25, our “sluggishness run” thus suggests that O3 reduces carbon assimilation more than transpiration (Figs. 2a, 2b). The “sluggishness run” can also explain the increase of transpiration measured by sap-flow at the Aspen FACE experiment (~18% in late summer under elevated O3 relative to control)15 and can justify the reduced late-season streamflow of forest watersheds under regionally elevated O3 exposure on the Appalachian foothills of the USA15.

Ozone decreased WUE in both the “sluggishness run” and “no sluggishness run” (Fig. 2c). A larger decline of WUE per unit O3 exposure or uptake, however, was found in the “sluggishness run” (up to 20%) relative to “no sluggishness run” (up to 5%) (Fig. 2c). Our result suggests that O3-induced stomatal sluggishness can significantly change forest carbon and water balances. This change partly explains the trend of forest WUE as observed at flux sites in North America26. Keenan et al.26 recently reported that forest WUE in North America increased over the last 15 years (approximately + 30%) and concluded that this increase resulted from increasing ambient CO2 concentration. The increase of WUE, however, was much greater than expected from theoretical and experimental evidence regarding plant response to CO227. Holmes28 pointed out that a decrease of daytime mean O3 concentration at North American forest sites (8–10 nmol mol−1 during the last 15 years), may partly explain the WUE trend (maximum 3-4% increase of WUE), based on literature data of WUE response to O3. According to our “sluggishness run”(Fig. 2c), we estimated a 2-3% increase of WUE by a 8–10 nmol mol−1 decrease in O3 concentrations, while only a ~1% increase of WUE was found in the “no sluggishness run” (Fig. 2c). This result suggests that a significant part of the WUE trend at North American sites (corresponding to about one-tenth of the observed WUE trend) may be explained by O3 effects, when O3-induced stomatal sluggishness is included.

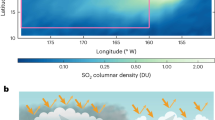

According to our “sluggishness run”, the contribution of O3 to the decline in WUE ranged from 4.5 ± 1.9 to 8.8 ± 3.0% in different regions of the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 3, S8). For example, the maximum difference (−8.8%) was found in China (Fig. 3), where relatively high level of O3 concentrations were shown (45 nmol mol−1 as daytime average, Fig. S4). Water limiting conditions (approximately 350 mm of precipitation from 1 May to 1 November from 2006–2009, data not shown) may decrease canopy cumulative O3 uptake in Central/West Asia (Fig. 3b) and reduce O3-induced impairment of forest WUE, even though O3 concentrations were relatively high (42 nmol mol−1 as daytime average) in this region (Fig. 3a).

Percent changes of reduction in modelled water use efficiency (WUE) in relation to daytime mean O3 concentration or canopy cumulative O3 uptake for several regions in the Northern Hemisphere (years 2006–2009). The percentage of reduction of WUE relative to “control run” (no O3 effect) was calculated by the offline coupling simulation of SOLVEG-MRI-CCM2 including O3-induced stomatal sluggishness. Plots and bars represent mean values and standard deviations, respectively. The five regions, i.e., Europe, North America, East Asia (without China), China and Central/West Asia are defined in Fig. S3.

In contrast with the frequent assumption that O3 reduces tree water use29, we demonstrated that O3-induced stomatal sluggishness has a potential to increase transpiration and thus explain observational evidence of reduced streamflow from forests15. Less efficient water use is expected to increase susceptibility of forest trees to drought and fire, which in turn are expected to increase in frequency and intensity due to climate change1. In addition to reduced carbon sequestration5,29, O3-increased transpiration can elevate air humidity and radiative forcing of water vapour relative to current estimates by global climate models9. Although further works are needed to assess the real-world impacts (e.g., verification of modelled O3 concentration and pre-industrial and future simulations), our results revealed that O3-induced stomatal sluggishness cannot be ignored when modelling biosphere-atmosphere interactions. This implies that stomatal sluggishness is essential to assessing impacts of air quality to terrestrial ecosystems under present and future atmospheric conditions.

Methods

A parameterization of stomatal conductance

Our parameterization of O3-induced stomatal sluggishness was based on leaf gas exchange data18 obtained from an O3-FACE experiment in Sapporo Experimental Forest, Hokkaido University, in northern Japan (43°04' N, 141°20' E, 15 m a.s.l., annual mean temperature: 9.3˚C, total precipitation: 1279 mm in 2012). Details of the exposure system are available in a previous paper30. Ozone was generated from pure oxygen by an O3 generator (Model PZ-1C, Kofloc, Kyoto, Japan). The resulting O3 was diluted with ambient air in a mixing tank and passed into the canopies through fluorine resin tubes hanging from a fixed grid above the trees down to a height of 50 cm above the ground. The target O3 concentration above the canopy was 60 nmol mol−1 during daylight hours. This concentrations of O3 corresponded to the legislative standard for O3 in Japan, where similar or higher O3 concentrations have often been observed in many regions, including forested areas31. This target concentration was also consistent with the level of elevated O3 concentrations applied in previous O3-FACE experiments14. This enhanced daytime O3 treatment was applied from August to November 2011 and from May to November 2012. The daytime hourly mean O3 concentrations in ambient and elevated O3 were 25.7 ± 11.4 nmol mol−1 and 56.7 ± 10.5 nmol mol−1 in 2011 and 27.5 ± 11.6 nmol mol−1 and 61.5 ± 13.0 nmol mol−1 in 2012. The average volumetric soil water content was large enough to avoid the water stress to trees (28.1 ± 2.8%).

We focused on Siebold’s beech, which is an O3 sensitive tree species30 widely distributed in cool-temperate climate. Diurnal course of leaf gas exchange was measured in fully expanded leaves exposed to full sun at the top of the canopy, using a portable infra-red gas analyzer (Model 6400, Li-Cor instruments, Lincoln, NE, USA) in June, August and October 2012 (see ref.18 for a detail). No difference in leaf gas exchange of Siebold’s beech between ambient and elevated O3 treatments was found before the start of fumigation11. There was also no difference in the leaf nitrogen content in August 201218. Measured data in each month were used to estimate the parameters of the Ball-Woodrow-Berry stomatal conductance model17 as follows:

where gmin is the minimum stomatal conductance (mol m−2 s−1), m is the Ball-Woodrow-Berry slope of the conductance-photosynthesis relationship (no dimension), An is net photosynthetic rate (μmol m−2 s−1), Rh is relative humidity at the leaf surface (no dimension) and Ca is CO2 concentration at the leaf surface (μmol mol−1). We parameterized monthly gmin as a function of cumulative O3 uptake of a leaf (CUO, mmol m−2) (Fig. 1), which was estimated by the DO3SE model (the fully empirical multiplicative stomatal conductance model) using meteorological and O3 concentration data at the experimental site. In contrast with the Ball-Woodrow-Berry model, the DO3SE model does not consider photosynthesis and modifies a reference value of stomatal conductance (denoted as maximum stomatal conductance, gmax) according to changes of environmental variables (i.e., light intensity, temperature, atmospheric humidity and soil moisture). In our previous study, the DO3SE model was parameterized by using data recorded for Siebold’s beech and by including O3 effects on stomatal conductance. The model showed a good agreement with the observation of stomatal conductance (R2 = 0.68).

To verify our result, we analyzed literature stomatal conductance data at Aspen FACE19, where terminal and lateral shoots from the upper and lower crown of an O3 sensitive aspen clone were measured in July after two years of O3 exposure to 55 nmol mol−1. Data points were obtained using the image analysis software SimpleDigitizer 3.2 (Haruyuki Fujimaki, Tokyo, Japan). Relative humidity (Rh) and CO2 concentration at the leaf surface (Ca) were set to 50% and 360 μmol mol−1, respectively, according to Noormets et al.19 We then calculated m and gmin at Aspen FACE (Fig. S2) and compared the results with those at the O3-FACE in Japan.

Modelling ozone effect in SOLVEG

We modified the parameters for calculating net photosynthetic rate (An) and stomatal conductance (gs) in SOLVEG in order to account for O3 effects based on CUO. SOLVEG calculates the O3 deposition flux (FO3) at each canopy layer (Supplementary Eq. (S1)) using stomatal resistance (rs) which equals the reciprocal of gs and quasi-laminar resistance over the leaves (rb)20,21:

where a (m2 m−3) is the leaf area density (LAD) at the canopy layer, Do3 and Dw (m2 s−1) are the diffusivities of O3 and water vapor, respectively and cO3 and cO3s (nmol mol−1) are the O3 concentrations in the canopy layer and sub-stomatal cavity, respectively. For simplicity, it was assumed that cO3s = 0 in Eq. (2) (ref. 32). CUO was calculated as temporal accumulation of FO3 at each canopy layer.

To calculate rs in Eq. (2), SOLVEG requires the maximum catalytic capacity of the photosynthetic enzyme system Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), Vcmax, at 25°C [Vcmax25; Supplementary Eqs. (S2)–(S5)], m and gmin as input parameters. In this study, all parameters were obtained from the results for Siebold’s beech in the O3 FACE in Japan18. The following fitting curves against CUO were applied to Vcmax25 and gmin: Vcmax25 = –0.887·CUO + 62.95 (Eq. 3; R2 = 0.94, p = 0.001), gmin = 0.03 + 0.09/[1 + exp{–0.21·(CUO – 24.7)}] (Eq. 4; Fig. 1, solid lines). The value of m was set to 15, which was the mean value during the experimental period. Ozone uptake at each canopy layer calculated by Eq. (2) was vertically integrated for all canopy layers to obtain canopy-scale O3 flux.

Simulation conditions of SOLVEG and MRI-CCM2

To investigate the O3 effects under different climate conditions, SOLVEG was applied to each horizontal grid of MRI-CCM2 temperate deciduous forests in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. S3). The Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA55: in the horizontal, 1.25° latitude/longitude regular grid resolution (The original horizontal resolution of JRA55 is a spectral triangular 319 with a reduced Gaussian grid, roughly equivalent to 0.5625° × 0.5625° lat-lon); in the vertical, 60 layers (L60) from the surface to 0.1 hPa)33 was used for input data to force the initial and upper boundary conditions of meteorological variables (atmospheric pressure, downward short- and long-wave radiations, precipitation, wind speed and air temperature and humidity near the surface) in SOLVEG. The parameters of canopy structures (leaf area index and canopy height) and CO2 concentration were set to be typical values (Table S1). Soil type was set to typical loam for all horizontal grids based on the harmonized world soil database34. At the initial day of calculations at each calculation year (1 May), soil temperature and moisture were given to each depth of soil by vertically interpolating the values of JRA55 data at the surface and bottom of the soil. Three sets of SOLVEG runs were carried out: 1) including both reduction of Vcmax25 (i.e., O3-induced decline of photosynthesis) and increase of gmin due to O3-induced stomatal sluggishness with an increase of CUO (“sluggishness run”), 2) including the reduction of Vcmax25 only (“no sluggishness run”) and 3) including no ozone effect (“control run”). The percentage variations of net CO2 assimilation, transpiration and WUE were calculated as the ratio of differences between “sluggishness run” or “no sluggishness run” and “control run”.

The MRI-CCM2 is used to generate 3-hourly averaged surface ozone concentration for SOLVEG calculations. The MRI-CCM222,23 is a global chemistry-climate model, in which an atmospheric chemistry model is coupled to the MRI’s latest atmospheric general circulation model (MRI-AGCM3) via a simple coupler. MRI-CCM2 was run for the period 2005–2009 and the simulation results between 2006 and 2009 were used for the SOLVEG calculations. In the simulation, the horizontal wind field was nudged toward JRA55 by using a Newtonian relaxation technique with a 24 h e-folding time. The horizontal spectral resolution was set to TL159, corresponding to a grid size of about 120 km. In the vertical, the model had 64 layers extending from the surface to the mesopause (0.01 hPa ≈ 80 km). The anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions used here were based on the Monitoring Atmospheric Composition and Climate and CityZen (MACCity) emissions dataset and the Global Fire Emissions Database version 3 (GFED3), respectively (Table S2). Concentrations of greenhouse gases were prescribed based on the fifth phase of the Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) RCP 6.0 scenario. The reproducibility of surface ozone concentration simulated by MRI-CCM2 was confirmed by comparing with observation data at northern mid-latitude monitoring sites: Waldhof (52.8°N, 10.8°E), Kovk(46.1°N, 15.1°E), Ryori (39.0°N, 141.8°E), Trinidad Head (41.1°N, 235.9°E), Algoma (47.0°N, 275.6°E) and Kejimkujik (44.4°N, 294.8°E) of the WMO World Data Centre for Greenhouse Gases (WDCGG) (http://gaw.kishou.go.jp/wdcgg.html). The six monitoring sites are located in the temperate deciduous forest grids (Fig. S3). Figure S9 shows that MRI-CCM2 can reproduce the seasonal variations in surface ozone at these monitoring sites with a normalized mean error of 0.5–11.9% and a normalized root-mean-square error of 9.0–17.9%.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: HOSHIKA, Y. et al. Ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness changes carbon and water balance of temperate deciduous forests. Sci. Rep. 5, 09871; doi: 10.1038/srep09871 (2015).

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Fifth Assessment Report. (2013) http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/index.shtml. (Date of access: 08/01/2015)

Monks, P. S. et al. Atmospheric composition change – Global and regional air quality. Atmos. Environ. 43, 5268–5350 (2009).

Vingarzan, R. A review of surface ozone background levels and trends. Atmos. Environ. 38, 3431–3442 (2004).

Young, P. J. et al. Pre-industrial to end 21st century projections of tropospheric ozone from the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2063–2090 (2013).

Sitch, S., Cox, P. M., Collins, W. J. & Huntingford, C. Indirect radiative forcing of climate change through ozone effects on the land-carbon sink. Nature 448, 791–795 (2007).

Karnosky, D., Percy, K. E., Chappelka, A. H., Simpson, C. & Pikkarainen, J. Air pollution, global change and forests in the new millennium. Develepments in Environmental Science Series, Oxford, UK. Elsevier, 2003).

Paoletti, E. & Grulke, N. E. Does living in elevated CO2 ameliorate tree response to ozone? A review on stomatal responses. Environ. Pollut. 137, 483–493 (2005).

Paoletti, E. & Grulke, N. E. Ozone exposure and stomatal sluggishness in different plant physiognomic classes. Environ. Pollut. 158, 2664–2671 (2010).

Lombardozzi, D., Levis, S., Bonan, G. & Sparks, J. P. Predicting photosynthesis and transpiration responses to ozone: decoupling modeled photosynthesis and stomatal conductance. Biogeosciences 9, 3113–3130 (2012).

Hoshika, Y., Omasa, K. & Paoletti, E. Whole-tree water use efficiency is decreased by ambient ozone and not affected by O3-induced stomatal sluggishness. Plos One, 7, e39270 (2012).

Hoshika, Y., Watanabe, M., Inada, N. & Koike, T. Ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness develops progressively in Siebold’s beech (Fagus crenata). Environ. Pollut. 166, 152–156 (2012).

Mills, G. et al. Evidence of widespread effects of ozone on crops and (semi-)natural vegetation in Europe (1990-2006) in relation to AOT40- and flux-based risk maps. Glob. Chan. Biol. 17, 592–613 (2011).

Paoletti, E. Ozone impacts on forests. CAB reviews: perspectives in agriculture, veterinary science. Nutrition Natural Resources. 2 No. 68, 1–13 (2007).

Karnosky, D. F. et al. Free-air exposure systems to scale up ozone research to mature trees. Plant Biol. 9, 181–190 (2007).

Sun, G. et al. Interactive influences of ozone and climate on streamflow of forest watersheds. Glob. Chan. Biol. 18, 3395–3409 (2012).

Watanabe, M., Hoshika, Y. & Koike, T. Photosynthetic responses of Monarch birch seedlings to differing timings of free air ozone fumigation. J. Plant Res. 127, 339–345 (2014).

Ball, J. T., Woodrow, I. E. & Berry, J. A. A model predicting stomatal conductance and its contribution to the control of photosynthesis under different environmental conditions. In: Biggens, J. eds. Progress in Photosynthesis Research. Dordrecht, pp. 221–224 (Netherlands. Martinus-Nijhoff Publishers, 1987).

Hoshika, Y., Watanabe, M., Inada, N. & Koike, T. Model-based analysis of avoidance of ozone stress by stomatal closure in Siebold’s beech (Fagus crenata). Ann. Bot. 112, 1149–1158 (2013).

Noormets, A. et al. Stomatal and non-stomatal limitation to photosynthesis in two trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.) clones exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 . Plant Cell Environ 24, 327–336 (2001).

Katata, G. et al. Development of an atmosphere-soil-vegetation model for investigation of radioactive materials transport in the terrestrial biosphere. Prog. Nuc. Sci. Tech. 2, 530–537 (2011).

Katata, G. et al. Coupling atmospheric ammonia exchange process over a rice paddy field with a multi-layer atmosphere-soil-vegetation model. Agr. For. Met. 180, 1–21 (2013).

Deushi, M. & Shibata, K. Development of a Meteorological Research Institute Chemistry-Climate Model version 2 for the study of tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry, Pap. Meteorol. Geophys. 62, 1–46, 10.2467/mripapers.62.1 (2011).

Yukimoto, S. et al. Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model Version 1(MRI-ESM1) —Model description—, Tech. Rep. Meteorol. Res. Inst. 64, 1–83 (2011).

Archibold, W. Temperate forest ecosystems. In: Archibold, W. eds. Ecology of World Vegetation. pp. 165–203 (U.K, Chapman & Hall, 1995).

Lombardozzi, D., Levis, S., Bonan, G. & Sparks, J. P. Integrating O3 influences on terrestrial processes: photosynthetic and stomatal response data available for regional and global modeling. Biogeosciences 10, 6815–6831 (2013).

Keenan, T. F. et al. Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature 499, 324–327 (2013).

Medlyn, B. E. & De Kauwe, M. Carbon dioxide and water use in forest plants. Nature 499, 287–289 (2013).

Holmes, C. D. Air pollution and forest water use. Nature 507, E1–E2 (2014).

Wittig, V. E., Ainsworth, E. A. & Long, S. P. To what extent do current and projected increases in surface ozone affect photosynthesis and stomatal conductance of trees? A meta-analytic review of the last 3 decades of experiments. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1150–1162 (2007).

Watanabe, M. et al. Photosynthetic traits of Siebold’s beech and oak saplings grown under free air ozone exposure. Environ. Pollut. 174, 50–56 (2013).

Izuta, T. Plants and environmental stresses (Corona Publisher, Tokyo, 2006, in Japanese).

Laisk, A., Kull, O. & Moldau, H. Ozone concentration in leaf intercellular air spaces is close to zero. Plant Physiol. 90, 1163–1167 (1989).

Ebita, A. et al. The Japanese 55-year Reanalysis “JRA-55”: an interim report. SOLA 7, 149–152 (2011).

FAO (Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) et al. Harmonized World Soil Database. (2012) http://webarchive.iiasa.ac.at/Research/LUC/External-World-soil-database/HTML/index.html?sb=1 (Date of access: 02/05/2014)

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Drs. Rüdiger Grote and Hans Peter Schmid, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (IMK-IFU) for their helpful comments and suggestions. The JRA-55 dataset was provided from the Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA-55) project by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). The MACCity and GFED3 data sets were downloaded from the Ether/ECCAD database. We would like to thank the WMO WDCGG for providing ozone measurement data. We are grateful for financial support to: the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund of Japan (5B-1102); the LIFE + project FO3REST (LIFE10 ENV/FR/208) and the FP7-Environment project ECLAIRE (282910) of the European Commission; and a Grant-in-aid from the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science (Type B 23380078, 26292075 and Young Scientists B 24710027 and ditto B 24780239, Postdoctoral fellowship for research abroad). This work was published within the IUFRO Task Force on Climate Change and Forest Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YH analyzed the data for ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness from the experiment performed by YH, MW and TK. MD conducted the global simulations of MRI-CCM2. GK modified SOLVEG to include ozone effects based on parameters obtained by YH and carried out simulations using the result of MD. EP contributed to the analyses. All authors were involved in writing the paper, although YH and EP took a lead role.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hoshika, Y., Katata, G., Deushi, M. et al. Ozone-induced stomatal sluggishness changes carbon and water balance of temperate deciduous forests. Sci Rep 5, 9871 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09871

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09871

This article is cited by

-

The effect of ozone on pine forests in South-Eastern France from 2017 to 2019

Journal of Forestry Research (2023)

-

Response of tropical trees to elevated Ozone: a Free Air Ozone Enrichment study

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2023)

-

Evaluating the Impacts of Ground-Level O3 on Crops in China

Current Pollution Reports (2021)

-

Trends in tropospheric ozone concentrations and forest impact metrics in Europe over the time period 2000–2014

Journal of Forestry Research (2021)

-

Poplar root anatomy after exposure to elevated O3 in combination with nitrogen and phosphorus

Trees (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.