Abstract

The concept of aromaticity has long played an important role in chemistry and continues to fascinate both experimentalists and theoreticians. Among the archetypal aromatic compounds, heteroaromatics are particularly attractive. Recently, substitution of a transition-metal fragment for a carbon atom in the anti-aromatic hydrocarbon pentalene has led to the new heteroaromatic osmapentalenes. However, construction of the aza-homolog of osmapentalenes cannot be accomplished by a similar synthetic manipulation. Here, we report the synthesis of aza-osmapentalenes by sequential ring contraction/annulation reactions of osmabenzenes via osmapentafulvenes. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra, X-ray crystallographic analysis and DFT calculations all suggest that these aza-osmapentalenes exhibit aromatic character. Thus, the stepwise transformation of metallabenzenes to metallapentafulvenes and then aza-metallapentalenes provides an efficient and facile synthetic route to these bicyclic heteroaromatics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As one of the most fundamental chemistry concepts, aromaticity has been continually investigated since Faraday's discovery of benzene in 18251 and Kekulé's famous alternating single- and double-bond cyclic structure proposed in 18652,3. The Hückel aromaticity rule4 is applied to cyclic compounds containing 4n + 2π electrons, but Möbius topologies favour 4n delocalized π electron counts5,6,7,8. In general, aromatic compounds are substantially more stable thermodynamically and anti-aromatic compounds less stable than appropriate non-aromatic reference systems. Synergistic interplay of theoretical and experimental investigations has led to the synthesis and characterisation of numerous aromatic molecules with interesting structural features and properties9,10. The incorporation of heteroatoms or related groups into aromatic hydrocarbons can result in various heteroaromatic compounds. These introduced heteroatoms are not limited to main-group atoms or related groups; they also include transition-metal fragments. As a result of the increasing structural and compositional variety of aromatic species, the definitions and criteria for characterising aromaticity have also been developing rapidly11.

Metallaaromatics12,13,14 are organometallic species derived from the replacement of a (hydro)carbon unit in conventional aromatic hydrocarbons with a transition-metal fragment. As typical metallaaromatic compounds, metallabenzene complexes have been extensively studied by both experimentalists and theoreticians, dating back to the first computationally proposed metallabenzene complexes by Thorn and Hoffman15 in 1979. The increase in the variety of the metallaaromatic family is further evidenced by the recent discovery of metallapyridines16,17,18, which are azaheterocyclic analogues of metallabenzenes. Very recently, efforts to expand the aromatic family has also led to the discovery of the first metallapentalene (osmapentalene)19,20, which has been shown to exhibit aromaticity. Theoretical computations reveal that all these osmapentalenes with planar metallacycle benefit from Craig-Möbius aromaticity. The involvement of transition-metal d orbitals in the π conjugation switches the Hückel anti-aromaticity of pentalene into the Möbius aromaticity of metallapentalene. The introduction of nitrogen atoms into the pentalene system lead to the heterocyclic analogs of pentalene which are broadly defined as azapentalenes. Similar to the parent pentalenes, azapentalenes are anti-aromatic by virtue of a 8-π-electron system21. Some azapentalene molecules that contain nitrogen atoms in the bridgehead positions can be considered as analogs of a pentalene dianion and these molecules are actually aromatic22. The isolation of the metallapentalene prompted us to investigate whether an aza-metallapentalene exists and, if so, how the synthesis could be achieved. As shown in Fig. 1, the structure of an aza-metallapentalene resembles that of pentalene, which is generally considered to be an anti-aromatic molecule, prompting us to consider whether an aza-metallapentalene, which is structurally and electronically analogous to metallapentalene, is also aromatic. In this paper, we present the synthesis and characterisation of aza-metallapentalenes, which were obtained from metallabenzenes via sequential ring contraction/annulation reactions.

Results

Synthesis of the first aza-metallapentalene

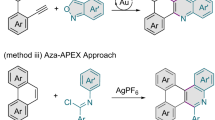

The recently reported osmapentalene19,20 was synthesised (derived) from the protonation of osmapentalyne (Fig. 2a). Experimentally, osmapentalyne23 was observed to be thermally stable and easy to prepare via the reaction of osmium complexes with terminal alkynes (Fig. 2a). Inspired by this observation, we initially attempted to react osmium complexes with a number of nitriles such as benzonitrile or acetonitrile in the hope of obtaining the corresponding aza-osmapentalynes. However, the expected reactions did not occur, only osmabenzenes or other osmacycles were detected, which have been previously reported24,25. Therefore, the preparation of an aza-metallapentalene via the synthesis of an aza-osmapentalyne followed by protonation is unfeasible.

Previously, we synthesised osmacyclopentadienes, each bearing an exocyclic C = N bond, by reacting an osmabenzene complex with amines26 (Fig. 2b). We envisioned that an aza-osmapentalene might be directly obtained by introducing a new carbon atom, with the intention of inducing a further annulation reaction yielding an osmacyclopentadiene monocyclic system, as illustrated by the retrosynthetic analysis shown in Fig. 2b.

We first modified an osmabenzene complex by ligand substitution to generate the more stable osmabenzene 1-I. The structure of osmabenzene 1-I was verified by X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 3b; the relevant experimental details are presented in Supplementary Figures and Methods). Subsequent treatment of 1-I with aniline in the presence of sodium hexafluorophosphate afforded the expected osmacyclopentadiene 2-PF6 in 95% yield (Fig. 3a). The complex 2-PF6 was characterised by multinuclear nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis and high-resolution mass spectroscopy. The structure of 2-PF6 is shown in Fig. 3c. The X-ray diffraction analysis demonstrated that 2-PF6 contains a coplanar metallacyclopentadiene ring with an exocyclic imino group. The structural parameters indicated that the metallacycle of 2-PF6 could be represented by two resonance structures, 2-PF6 and 2b-PF6 (Fig. 3a), with 2-PF6 as the more dominant structure. The structural data (averaged bond lengths) also indicated that both the metallacycles in 1-I and 2-PF6 have delocalised structures. In addition, the six atoms Os1 and C1-C5 in each complex are approximately coplanar, which is reflected by their small mean deviation (0.0129 Å for 1-I; 0.0331 Å for 2-PF6) from the least-squares plane.

Synthesis of osmacyclopentadiene 2-PF6.

(a) The reaction of osmabenzene 1-I with aniline produces osmacyclopentadiene 2-PF6. (b, c) X-ray structures of 1-I (b) and 2-PF6 (c) (50% probability level). Phenyl moieties in PPh3, the counter anion and the solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) for 1-I: Os1-C1 2.065(7), Os1-C5 1.956(7), C1-C2 1.359(10), C2-C3 1.432(11), C3-C4 1.345(10), C4-C5 1.407(11), C4-I1 2.131(7), Os1-C01 1.925(8), C01-O01 1.145(9), Os1-I2 2.8161(8). Selected bond lengths (Å) for 2-PF6: Os1-C1 2.004(6), Os1-C4 2.183(7), Os1-I1 2.8347(5), C1-C2 1.372(9), C2-C3 1.430(9), C3-C4 1.386(9), C4-C5 1.418(9), C5-N1 1.309(8), Os1-C01 1.880(9), C01-O01 1.109(8).

As shown in Fig. 3a, the resonance structure 2b-PF6 (metallapentafulvene) contributes to the overall structure of the complex 2-PF6. Since pentafulvene molecules27 are normally considered aromatic, we assume that the metallapentafulvene 2-PF6 is also aromatic, as is indeed supported by our density functional theory (DFT) results (vide infra).

According to the retrosynthetic analysis shown in Fig. 2b, the complex 2-PF6 could be used as the precursor to afford the desired aza-metallapentalene by introducing an additional carbon atom. To test this idea, reactions of 2-PF6 with the propynols RCH(OH)C ≡ CH in the presence of Ag2O were carried out in the hope of obtaining the desired aza-osmapentalene complexes. Triethylamine was used in the reactions to ensure that an acetylide ligand could be easily delivered to the osmium metal centre (Warning: the reaction may proceed through the formation of silver acetylide, which decomposes violently on contact with moisture and water producing highly flammable and explosive acetylene gas and causing fire and explosion hazard). As shown in Fig. 4a, treatment of 2-PF6 with phenylpropynol in the presence of Ag2O and triethylamine under reflux for approximately 3 h led to the formation of complex 3a-PF6, which was isolated in 81% yield. The complex 3a-PF6 was characterised by NMR spectroscopy and HRMS and its structure was determined by X-ray crystal structure analysis.

Synthesis of aza-osmapentalene 4-(PF6)2.

(a) The reaction of osmacyclopentadiene 2-PF6 with substituted propynols followed by dehydroxylation produces aza-osmapentalene 4-(PF6)2. (b, c) X-ray structures of 3a-PF6 (b) and 4a-(PF6)2 (c) (50% probability level). Phenyl moieties in PPh3, the counter anion and the solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) for 3a-PF6: Os1-C1 2.040(8), Os1-C4 2.100(7), Os1-C6 2.180(9), C1-C2 1.381(11), C2-C3 1.450(11), C3-C4 1.373(12), C4-C5 1.377(13), C5-N1 1.313(11), C6-N1 1.483(11), C6-C7 1.338(12), C7-C8 1.489(12), C8-O1 1.430(12). Selected bond lengths (Å) for 4a-(PF6)2: Os1-C1 2.041(4), Os1-C4 2.069(4), Os1-C6 2.082(4), C1-C2 1.407(5), C2-C3 1.410(5), C3-C4 1.394(5), C4-C5 1.381(5), C5-N1 1.374(5), C6-N1 1.396(5), C6-C7 1.465(5), C7-C8 1.337(5).

Complex 3a-PF6 exhibits an essentially planar metal-bridged bicyclic structure (Fig. 4b). The mean deviation from the least-squares plane through Os1, N1 and C1-C6 is 0.0383 Å. The Os1-C6 bond length (2.180(9) Å) is appreciably longer than both the Os1-C1 bond length (2.040(8) Å) and the Os1-C4 bond length (2.100(7) Å). The three Os-C bond lengths of the metallabicycle all lie in the high end of the reported range for typical Os-C(vinyl)28 bond lengths (1.859–2.359 Å) (on the basis of a search of the Cambridge Structural Database, CSD version 5.35, conducted in November, 2013). In addition, the structural parameters indicate a considerable bond distance alternation within the two fused five-membered rings. Therefore, the complex 3a-PF6 is not the desired aza-osmapentalene, although the osmabicyclic framework is consistent with the suppositional aza-osmapentalene formula.

The hydroxyl group in 3a-PF6 was easily removed to afford the desired complex 4a-(PF6)2 by treatment of 3a-PF6 with NaPF6. The complex 4a-(PF6)2 was isolated as a red solid in 98% yield and was characterised by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy and HRMS. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction established the solid-state structure of 4a-(PF6)2 unambiguously, demonstrating its aza-osmapentalene arrangement. As shown in Fig. 4c, the two fused five-membered rings of 4a-(PF6)2 are nearly coplanar. The mean deviation from the least-squares plane through Os1, N1 and C1-C6 is only 0.0154 Å. All the bond distances within the two fused rings fall within the range observed for other typical metallaaromatics12,13,14. The three Os-C distances are nearly equal (Os1-C1 2.041(4), Os1-C4 2.069(4), Os1-C6 2.082(4) Å) and the ring C-C/C-N distances are consistent with extensive delocalisation within the metallacycle (C1-C2 1.407(5), C2-C3 1.410(5), C3-C4 1.394(5), C4-C5 1.381(5), C5-N1 1.374(5), C6-N1 1.396(5) Å). The aromaticity in the metallacyclic rings is also clearly evident in the NMR spectra. In particular, the 1H NMR spectrum shows three strongly downfield 1H signals corresponding to the ring protons at δ = 14.3 (C1H), 10.0 (C3H) and 9.9 (C5H) ppm. With the aid of the 1H-13C HSQC and 13C-DEPT 135 spectra, we observed the signals for the six carbon atoms of the osmabicycle at δ = 248.5 (C1), 151.0 (C2), 171.9 (C3), 187.6 (C4), 163.0 (C5) and 234.1 (C6) ppm in the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum.

Thus, using the strategy outlined in Fig. 2b, we successfully synthesised the first aza-metallapentalene complex in three steps starting from the six-membered osmabenzene complex 1-I. Further investigations demonstrated that this synthetic strategy could be extended to prepare other aza-osmapentalene complexes with other substituents on the metallacycle. The vinyl-containing aza-osmapentalene 4b-(PF6)2 was obtained from the reaction of 2-PF6 with propynol (Fig. 4a) and was isolated as a brown solid. Similarly, the butenynyl-containing aza-osmapentalene 4c-(PF6)2 was obtained from the reaction of 2-PF6 with penta-1,4-diyn-3-ol and was isolated as a dark-brown solid (Fig. 4a).

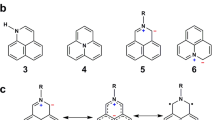

As previously mentioned, X-ray crystallography revealed a planar structure with no alternation in the carbon–carbon bond lengths of the osmabicyclic rings in the aza-osmapentalene 4a-(PF6)2. Protons on the periphery of aromatic compounds are well known to have relatively large downfield NMR spectroscopic chemical shifts due to a diamagnetic ring current. Fig. 5a shows a comparison of the chemical shifts of three specific protons among four different metallacyclic complexes. Compared with the structurally similar complex 3a, complex 4a gave considerable downfield chemical shifts because of its aromatic character. The 1H NMR chemical shifts as well as the X-ray diffraction data indicate that the metallacycle in the cation of 4-(PF6)2 has a delocalised structure, with contributions from the six resonance structures 4 to 4E, as shown in Fig. 5b. Consistent with their aromaticity, all of the new aza-osmapentalenes exhibit remarkably high thermal stability. Solid samples of 4-(PF6)2 were heated in air at 160°C for at least 5 h without noticeable decomposition. 4-(PF6)2 was stable even at 80°C in 1,2-dichloro-ethane solution for 5 h. These new aza-osmapentalenes each contain a phosphonium substituent, which is also believed to partially contribute to the high stability29.

Aromaticity of aza-osmapentalenes: downfield 1H chemical shifts and resonance structures.

(a) The proton chemical shifts (ppm vs. tetramethylsilane) of the ring protons of osmabenzene 1, osmapentafulvene 2, osmabicycle 3a and aza-osmapentalyne 4a. (b) Six possible resonance structures for the aza-osmapentalenes 4.

DFT calculations of osmabenzene, osmacyclopentadiene and aza-osmapentalene

To gain more insight into the electronic structure and aromaticity of the aza-osmapentalenes 4, we performed density functional theory (DFT, B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p)) calculations. The nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS)30,31,32 values were computed for the metallacycle rings of complexes 1-I, 2-PF6 and 4-(PF6)2. In general, negative NICS values indicate aromaticity, whereas positive values suggest anti-aromaticity. As shown in Fig. 6a, the calculated NICS(1) values are −2.6 and −1.6 ppm for the rings in osmabenzene 1 and osmapentafulvene 2, respectively. (When the environments at points 1 Å above and below the ring centres are not equivalent, the averaged values were used for NICS(1) values.) These values are comparable to those reported for other metallaaromatics19,20,23,31,33,34,35,36. The NICS(1) values for the two five-membered rings of aza-osmapentalene 4a are also negative (−6.7 and −6.9 ppm), in sharp contrast with those of azapentalene (+22.2 and +15.8 ppm). We also evaluated the aromatic stabilisation energy (ASE) by employing the isomerisation method introduced by Schleyer and Pühlhofer37. For model complexes 1′, 2′ and 4a′, ASE values of 11.3, 10.1 and 26.2 kcal/mol were calculated, respectively; these values contrast sharply with the negative ASE value (−4.3 kcal mol−1) calculated for azapentalene. The calculated ASE value for the aza-osmapentalene 4a′ is close to the previously reported values for osmapentalenes19,20. The negative NICS values and the significant ASE values calculated for these model complexes indicate that aromaticity is closely associated with the metallacycle rings in complexes 1, 2 and 4a.

Evaluation of aromaticity for osmabenzene 1, osmapentafulvene 2, osmacycle 3 and aza-osmapentalyne 4a by DFT calculations.

(a) The NICS values calculated for the rings in osmabenzene 1, osmapentafulvene 2, osmacycle 3 and aza-osmapentalyne 4a. (b) The ASE values calculated for the model complexes osmabenzene 1′, osmapentafulvene 2′, osmacycle 3′ and aza-osmapentalyne 4a′. The energies computed at the B3LYP level using the LanL2DZ basis set for osmium and the 6-311++G(d,p) basis sets for carbon and hydrogen include zero-point energy corrections.

Additional evidence for the aromatic nature of aza-osmapentalene 4 was provided by examination of the molecular orbitals calculated for the further simplified model complex 4a″. π Electrons are normally responsible for aromatic behaviour. Therefore, our attention is paid to those occupied orbitals. As shown in Fig. 7a, the five occupied π molecular orbitals (MOs) calculated for 4a″ (HOMO-1, HOMO-2, HOMO-3, HOMO-7 and HOMO-18) reflect the π-delocalisation along the perimeter of the bicyclic system. HOMO-1, HOMO-3 and HOMO-18 are derived from the orbital interactions between the pπ atomic orbitals of the C6NH6 unit (perpendicular to the bicycle plane) and the Os 5dxz orbital, whereas HOMO-2 and HOMO-7 are formed by the orbital interactions between the pπ atomic orbitals of the C6NH6 unit and the Os 5dyz orbital. The approximately uniform contribution of pπ orbitals from ring atoms in each of these occupied π molecular orbitals is typical for and consistent with a delocalised π molecular system. The four occupied π MOs calculated for the anti-aromatic azapentalene are also presented in Fig. 7b for comparison.

Conclusion

We synthesised the first examples of aza-metallapentalenes using metallabenzenes as the starting material. The synthetic route to these aza-metallapentalenes is particularly interesting and remarkable. The bicyclic eight-membered ring complexes are derived from sequential ring contractions, followed by annulation reactions of the six-membered metallabenzenes via the five-membered metallapentafulvenes. Both experimental and theoretical studies suggest that the metallabenzenes, metallapentafulvenes and aza-metallapentalenes all exhibit aromatic character. The present results not only expand the aromaticity concept but also open a promising avenue for the construction of new bicyclic metallaaromatics containing main-group heteroatoms.

Methods

General considerations

Unless otherwise stated, all manipulations were carried out at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques unless otherwise stated. Solvents were distilled from sodium/benzophenone (diethyl ether) or calcium hydride (dichloromethane) under N2 prior to use. The starting material [OsCl2(PPh3)3]38, HC ≡ CCH(OH)C ≡ CH39 and the osmabenzene [Os{CHC(PPh3)CHCICH}I2(PPh3)2] was synthesised according to the previously published procedure24. Other reagents were used as received from commercial sources without further purification. Further experimental details and the synthetic procedures for 1-I, 3b-PF6, 3c-PF6, 4b-(PF6)2 and 4c-(PF6)2 are described in the Supplementary Methods. The procedures for 2-PF6, 3a-PF6and 4a-(PF6)2 are described below.

Synthesis of osmapentafulvene complex 2-PF6

Aniline (60 μL, 0.66 mmol) was added to a mixture of 1-I (300 mg, 0.21 mmol) and sodium hexafluorophosphate (71 mg, 0.42 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (25 mL). The mixture was heated at reflux for approximately 10 h to afford a purple suspension. The solid suspension was removed by filtration and the volume of the filtrate was reduced to approximately 2 mL under vacuum. The addition of ether (20 mL) to the solution then produced a purple solid that was collected by filtration, washed with diethyl ether (3 × 2 mL) and dried under vacuum. Yield: 282 mg, 95%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 11.9 (d, J(PH) = 15.6, 1 H, C1H), 10.8 (d, J(HH) = 14.6, 1 H, NH), 7.9 (d, J(HH) = 14.6, 1 H, C5H), 7.7 (br, 1 H, C3H), 6.6–7.8 ppm (m, 50H, Ph); 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 13.0 (s, CPPh3), −3.1 (s, OsPPh3), −144.4 ppm (septet, PF6); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD2Cl2, plus 1H-13C HSQC and 13C-dept 135): δ = 225.2 (br, C1), 189.7 (br, C4), 175.5 (d, J(PC) = 22.0, C3), 169.3 (s, C5), 158.8 (br, Os(CO)), 137.2–118.1 (m, Ph), 122.0 (d, J(P,C) = 82.2 Hz, C2); HRMS (ESI): [M-PF6]+ calcd for [C66H54NP3IOOs]+, 1288.2072; found, 1288.2091; analysis (calcd., found for C66H54F6INOOsP4): C (55.35, 55.24), H (3.80, 3.72), N (0.98, 1.29).

Synthesis of osmabicyclic complex 3a-PF6

A mixture of (Ph)CH(OH)C ≡ CH (40 mg, 0.30 mmol) Ag2O (60 mg, 0.26 mmol), NEt3 (1 mL) and 2-PF6 (365 mg, 0.25 mmol) in dichloromethane (30 mL) was heated at reflux for 3 h to afford a blue suspension (Warning: the reaction may proceed through the formation of silver acetylide, which decomposes violently on contact with moisture and water producing highly flammable and explosive acetylene gas and causing fire and explosion hazard). The solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 5 mL). The volume of the filtrate was filtered through a Celite pad to remove the silver salt and was subsequently reduced to approximately 2 mL under vacuum. Diethyl ether (20 mL) was added slowly with stirring to afford a blue solid, which was collected by filtration, washed with hexane (3 × 3 mL) and dried under vacuum. Yield: 296 mg, 81%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 11.4 (d, J(P,H) = 20.6 Hz, 1 H, C1H), 7.5 (br, 1 H, C3H), 7.1 (s, 1 H, C5H), 6.9–7.9 (m, 55 H, Ph), 5.9 (d, J(H,H) = 8.8 Hz, 1 H, C7H), 5.3 (d, J(H,H) = 8.8 Hz, 1 H, C8H), 0.9 ppm (br, 1 H, OH); 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 12.2 (s, CPPh3), 3.5 (d, J(P,P) = 218.6 Hz, OsPPh3), 1.0 (J(P,P) = 218.6 Hz, OsPPh3), −144.4 ppm (septet, PF6); 1C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD2Cl2, plus 13C-DEPT 135, 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMBC): δ = 233.0 (br, C1), 196.0 (br, C4), 178.6 (br, C9), 169.0 (s, C5), 163.7 (br, C6), 161.5 (d, J(P,C) = 25.1 Hz, C3), 131.8 (s, C7), 123.7 (d, J(P,C) = 90.9 Hz, C2), 120.6–144.6 (m, Ph), 77.9 (s, C8); HRMS (ESI): [M-PF6]+ calcd for [C75H61NP3O2Os]+, 1292.3524; found, 1292.3542; analysis (calcd., found for C75H61F6NO2OsP4): C (62.71, 62.37), H (4.28, 4.19), N (0.98, 1.38).

Synthesis of aza-osmapentalene complex 4a-(PF6)2

A mixture of 3a-PF6 (200 mg, 0.14 mmol) and sodium hexafluorophosphate (28 mg, 0.17 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 30 min to afford a red suspension. The solid suspension was removed by filtration and the volume of the filtrate was reduced to approximately 2 mL under vacuum. The addition of diethyl ether (20 mL) to the solution then produced a red solid that was collected by filtration, washed with diethyl ether (3 × 2 mL) and dried under vacuum. Yield: 213 mg, 98%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 14.3 (d, J(P,H) = 16.5 Hz, 1 H, C1H), 10.0 (br, 1 H, C3H), 9.9 (s, 1 H, C5H), 6.4–7.9 (m, 55 H, Ph), 7.7 (d, J(H,H) = 15.2, 1 H, C8H), 6.3 (d, J(H,H) = 15.2, 1 H, C7H); 31P{1H} NMR (122 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 14.7 (s, CPPh3), 1.6 ppm (s, OsPPh3), −144.4 ppm (septet, PF6); 13C{1H} NMR (76 MHz, CD2Cl2 and 13C-DEPT 135, 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMBC): δ = 248.5 (br, C1), 234.1 (br, C6), 191.3 (br, C9), 187.6 (br, C4), 171.9 (d, J(P,C) = 21.4 Hz, C3), 163.0 (s, C5), 158.9(s, C8), 151.0 (d, J(P,C) = 67.3 Hz, C2), 135.4 (s, C7), 117.9–140.5 (m, Ph); HRMS (ESI): [(M-2PF6)/2]+ calcd for [(C75H60NP3OOs)/2]+, 637.6746; found, 637.6763; analysis (calcd., found for C75H60F12NOOsP5): C (57.58, 57.86), H (3.87, 3.91), N (0.90, 1.30).

X-ray Crystallographic Analysis

Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from a dichloromethane solution layered with hexane. Diffraction data were collected on an Oxford Gemini S Ultra charge-coupled device (CCD) area detector (2-PF6, 3a-PF6, 4a-(PF6)2 and 4b-(PF6)2) or on a Bruker Apex CCD area detector (1-I) using graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) or Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). Semi-empirical or multi-scan absorption corrections (SADABS) were applied40. All structures were solved by the Patterson function, completed by subsequent difference Fourier map calculations and refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2 with all the data using the SHELXTL program package41. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically unless otherwise stated. Hydrogen atoms were placed at idealised positions and were refined using a riding model. See Supplementary Methods for detailed crystal data related to complexes 1-I, 2-PF6, 3a-PF6, 4a-(PF6)2 and 4b-(PF6)2.

Computational details

All structures were optimised at the B3LYP level of DFT42,43,44. In addition, the frequency calculations were performed to confirm the characteristics of the calculated structures as minima. In the B3LYP calculations, the effective core potentials (ECPs) of Hay and Wadt with a double-ζ valence basis set (LanL2DZ) were used to describe the Os, P and I atoms, whereas the standard 6-311++G(d,p) basis set was used for the C and H atoms45 for all the ASE calculations. Polarisation functions were added for Os (ζ(f) = 0.886), I (ζ(d) = 0.266) and P (ζ(d) = 0.34)46 in all of the calculations. NICS values were calculated at the B3-LYP-GIAO/6-311++G(d,p) level. All the optimisations were performed with the Gaussian 03 software package47. See Supplementary Materials for the Cartesian coordinates.

Additional information

Accession codes: The X-ray crystal structure information is available at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC-1013726 (1-I), CCDC-1013727 (2-PF6), CCDC-1013728 (3a-PF6), CCDC-1013729 (4a-(PF6)2) and CCDC-1013730 (4b-(PF6)2). These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Faraday, M. On new compounds of carbon and hydrogen and on certain other products obtained during the decomposition of oil by heat. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 115, 440–446 (1825).

Kekulé, F. A. Sur la constitution des substances aromatiques. Bull. Soc. Chim. 3, 98–111 (1865).

Kekulé, F. A. Note sur quelques produits de substitution de la benzine. Bull. Acad. R. Belg. 19, 551–563 (1865).

Hückel, E. Quantum-theoretical contributions to the benzene problem. I. The electron configuration of benzene and related compounds. Z. phys. 70, 204–286 (1931).

Craig, D. P. A novel type of aromaticity. Nature 181, 1052–1053 (1958).

Heilbronner, E. Hückel molecular orbitals of Möbius-type conformations of annulenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 5, 1923–1928 (1964).

Rzepa, H. S. Möbius aromaticity and delocalization. Chem. Rev. 105, 3697–3715 (2005).

Mauksch, M., Gogonea, V., Jiao, H. & Schleyer, P. V. R. Monocyclic (CH)9+—a Heilbronner Möbius aromatic system revealed. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 2395–2397 (1998).

Garratt, P. J. Aromaticity (Wiley, 1986).

Minkin, V. I., Glukhovtsev, M. N. & Simkin, B. Y. Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity: Electronic and Structural Aspects (Wiley, 1994).

Schleyer, P. v. R. Thematic issue “Aromaticity”. Chem. Rev. 101, 115–1566 (2001).

Cao, X.-Y., Zhao, Q., Lin, Z. & Xia, H. The chemistry of aromatic osmacycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 341–354 (2014).

Chen, J. & Jia, G. Recent development in the chemistry of transition metal-containing metallabenzenes and metallabenzynes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257, 2491–2521 (2013).

Frogley, B. J. & Wright, L. J. Fused-ring metallabenzenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 270–271, 151–166 (2014).

Thorn, D. L. & Hoffmann, R. Delocalization in metallocycles. Nouv. J. Chim. 3, 39–45 (1979).

Weller, K. J., Filippov, I., Briggs, P. M. & Wigley, D. E. Pyridine degradation intermediates as models for hydrodenitrogenation catalysis: preparation and properties of a metallapyridine complex. Organometallics 17, 322–329 (1998).

Liu, B. et al. Osmapyridine and osmapyridinium from a formal [4 + 2] cycloaddition reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 5430–5434 (2009).

Wang, T. et al. Synthesis and characterization of a metallapyridyne complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9838–9841 (2012).

Zhu, C. et al. Planar Möbius aromatic pentalenes incorporating 16 and 18 valence electron osmiums. Nat. Commun. 5, 3265–3271 (2014).

Zhu, C. et al. A metal-bridged tricyclic aromatic system: synthesis of osmium polycyclic aromatic complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 6232–6236 (2014).

Hafner, K. & Schmidt, F. A Stable 2-Azapentalene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 12, 418–419 (1973).

Elguero, J., Claramunt, R. M. & Summers, A. J. H. The chemistry of aromatic azapentalenes. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 22, 183–320 (1978).

Zhu, C. et al. Stabilization of anti-aromatic and strained five-membered rings with a transition metal. Nat. Chem. 5, 698–703 (2013).

Xia, H. et al. Osmabenzenes from the Reactions of HC ≡ CCH(OH)C ≡ CH with OsX2(PPh3)3 (X = Cl, Br). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6862–6863 (2004).

Gong, L. et al. Osmabenzenes from osmacycles containing an η2-coordinated olefin. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 6258–6266 (2009).

Wang, T. et al. cine-Substitution reactions of metallabenzenes: an experimental and computational study. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 10982–10991 (2013).

Erker, G. Syntheses and reactions of fulvene-derived substituted aminoalkyl-Cp and phosphinoalkyl-Cp-Group 4 metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 250, 1056–1070 (2006).

Esteruelas, M. A., López, A. M. & Oliván, M. Osmium–carbon double bonds: formation and reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 251, 795–840 (2007).

Zhao, Q. et al. Stable isoosmabenzenes from a formal [3 + 3] cycloaddition reaction of metal vinylidene with alkynols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 1354–1358 (2011).

Schleyer, P. V. R., Maerker, C., Dransfeld, A., Jiao, H. & Hommes, N. J. R. V. E. Nucleus-independent chemical shifts: a simple and efficient aromaticity probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6317–6318 (1996).

Chen, Z., Wannere, C. S., Corminboeuf, C., Puchta, R. & Schleyer, P. V. R. Nucleus-independent chemical shifts (NICS) as an aromaticity criterion. Chem. Rev. 105, 3842–3888 (2005).

Fallah-Bagher-Shaidaei, H., Wannere, C. S., Corminboeuf, C., Puchta, R. & Schleyer, P. V. R. Which NICS aromaticity index for planar π rings is best? Org. Lett. 8, 863–866 (2006).

Mauksch, M. & Tsogoeva, S. B. Demonstration of “Möbius” aromaticity in planar metallacycles. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 7843–7851 (2010).

Iron, M. A., Lucassen, A. C. B., Cohen, H., van der Boom, M. E. & Martin, J. M. L. A computational foray into the formation and reactivity of metallabenzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11699–11710 (2004).

Periyasamy, G., Burton, N. A., Hillier, I. H. & Thomas, J. M. H. Electron delocalization in the metallabenzenes: a computational analysis of ring currents. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 5960–5972 (2008).

Han, F., Wang, T., Li, J., Zhang, H. & Xia, H. m-Metallaphenol: synthesis and reactivity studies. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 4363–4372 (2014).

Schleyer, P. V. R. & Pühlhofer, F. Recommendations for the evaluation of aromatic stabilization energies. Org. Lett. 4, 2873–2876 (2002).

Hoffmann, P. R. & Caulton, K. G. Solution structure and dynamics of five-coordinate d6 complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 4221–4228 (1975).

Jones, E. R. H., Lee, H. H. & Whiting, M. C. Researches on acetylenic compounds. Part LXIV.* The preparation of conjugated octa- and deca-acetylenic compounds. J. Chem. Soc. 3483–3489 (1960).

Sheldrick, G. M. SADABS, Program for Semi-Empirical Absorption Correction (University of Göttingen, Göttingen: Germany, 1997).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXTL (Siemens Analytical X-ray Systems, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 1995).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Miehlich, B., Savin, A., Stoll, H. & Preuss, H. Results obtained with the correlation energy density functionals of Becke and Lee, Yang and Parr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 157, 200–206 (1989).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 37, 785–789 (1988).

Hay, P. J. & Wadt, W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for potassium to gold including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 299–310 (1985).

Huzinaga, S. Gaussian Basis Sets for Molecular Calculations (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1984).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 03, Revision E.01 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2004).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21272193 and 21332002) and the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (HKUST603313).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X. and H.Z. designed the research. T.W., H.H. and J.L. performed the experiments. T.W. and F.H. recorded all NMR data and solved all X-ray structures. H.X., H.Z. and T.W. analysed the experimental data. H.Z. performed the theoretical computations and analysed the theoretical data with assistance from Z.L. and J.Z. H.Z. wrote the paper with assistance from Z.L. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation of the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Han, F., Huang, H. et al. Synthesis of Aromatic Aza-metallapentalenes from Metallabenzene via Sequential Ring Contraction/Annulation. Sci Rep 5, 9584 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09584

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09584

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.