Abstract

Research on sex differences in renal cancer-specific mortality (RCSM), which considered the sex effect to be constant throughout life, has yielded conflicting results. This study hypothesized the sex effect may be modified by age, which is a proxy for hormonal status. Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database (1988–2010) were used to identify 114,539 patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The study cohort was divided into three age groups using cutoffs of 42 and 58 years, which represent the premenopausal and postmenopausal periods. The cumulative incidence function and competing risks analyses were used to examine the effect of covariates on RCSM and other-cause mortality (OCM). In premenopausal period, male sex was a significant predictor of poor RCSM for both localized (adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio [aSHR] = 1.63, P = 0.002) and advanced (aSHR = 1.20, P = 0.041) disease. In postmenopausal period, the sex disparity diminished (aSHR = 1.05, P = 0.16) and reversed (aSHR = 0.95, P = 0.017) in localized and advanced disease, respectively. On the contrary, similar trend was not found for OCM across all age groups. Our results demonstrated the sex effect on RCSM was strongly modified by age. These findings may aid in clinical practice and need further evaluation of underlying biological mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal cancer is the 13th most common malignancy globally and it has increased by about 2% annually during the last two decades1. In 2013, an estimated 65,150 new cases of renal cancer were diagnosed in the United States and 13,680 died of the disease2. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which accounts for approximately 90% of all renal malignancies, represented 5% of all cancers in men and 3% of all cancers in women in the United States in 20132,3. Overall, the incidence of RCC is about 1.6 to 2.0 times higher in men than women and men account for almost two thirds of all deaths from RCC2,3,4.

Current evidence suggests that the protective role of sex in the incidence of RCC may extend to mortality. Results from a multi-institutional sample of 6234 patients with RCC found significant sex differences in outcomes, with women having better disease-specific survival (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75) and overall survival (HR = 0.80) compared with men5. Rampersaud et al.6, who studied 5654 RCC patients treated at 10 international academic centers, reported that women had a 19% reduced risk of death compared with men (HR = 0.81). The observed female survival advantage is also supported by biological research. Among all plausible contributing factors, estrogen is most commonly discussed7,8,9,10. A study by Yu et al.7 found that estrogen, through estrogen receptor (ER) β, inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of RCC cells and increased RCC apoptosis by affecting the expression of growth factor-related downstream genes and apoptotic genes. Nevertheless, other epidemiological studies have failed to support a sex effect on RCC-specific survival4,11. It should be noted that the peak incidence of RCC occurs in the sixth and seventh decades, during which sex difference in hormones decrease. Therefore, the age-associated changes in sex hormones may be one reason for the conflicting results of sex and survival outcomes.

In the current study, we hypothesized that the effect of sex on oncologic outcomes is modified by age, which was used as a surrogate for hormone status. To test our hypothesis, we examined the sex effect across age categories on renal cancer-specific mortality (RCSM) in patients with RCC from the population-based Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. Moreover, since other-cause mortality (OCM) accounts for substantial mortality outcomes in RCC, we used competing risks analyses to estimate RCSM, which can provide unbiased survival estimates.

Results

Demographic and disease characteristics

Of 114,539 enrolled patients, 72,050 (62.90%) were men and 42,489 (37.10%) were women (sex ratio = 1.70). Table 1 summarizes the demographic and disease characteristics stratified by the age and sex. Younger and older patients were similar in terms of registry area, SES, tumor size and the percentage of clear cell RCC. However, young patients were likely to be black, have localized disease and low-grade disease and to have undergone surgical interventions, compared with older patients. Sex comparisons revealed that more older men were married (74.16%) whereas more older women were unmarried (48.91%). Moreover, pathological subtypes of RCC showed a predominance of chromophobe (9.25%) and a lower probability of papillary (4.78%) in young women. Sex differences in tumor size and SEER stage, which may be influenced by the prevalence of early detection, were small across the different age groups (Table 1).

At last follow-up, 20,597 (17.98%) patients died from RCC and 21,487 (18.76%) succumbed to other causes. The median duration of follow-up was 68 months (95% CI, 67.45–68.55 months). Young patients had lower RCSM and OCM compared with their old counterparts. It is worth noting that RCSM was higher than OCM in young patients; nevertheless, OCM was more common in old patients. The lowest RCSM was observed in young females (Table 1).

Sex difference in mortality stratified by age

Cumulative incidence curves were constructed for localized disease and regional/distant disease, according to age and sex (Figure 1). Young women had the lowest RCSM among the six age and sex subgroups for localized disease and sex differences in RCSM narrowed remarkably in older patients. However, OCM, which increased with age, was lower in females than males across all age groups. We observed a similar age-dependent sex effect on mortality for regional/distant disease. Since most of the RCSM occurred in 2 years in advanced disease, the difference in survival was moderate.

We also examined the difference in conditional mortality for patients who had already survived 1 year after being registered in the database. The mortality curves were quite similar to the unconditioned curves, which indicated that treatment-related short-term mortality was unlikely to explain sex-related difference in survival (Supplemental Figure).

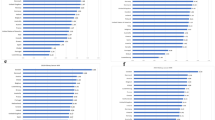

The crude SHRs of sex on cause-specific mortalities in each age group are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Figure 2, which depicts the adjusted effect of sex on cause-specific mortalities in each age group, indicates a decreasing SHR on RCSM with increasing age. This phenomenon is especially notable for localized disease. In young patients, being female was a significant predictor of lower RCSM (SHR = 1.63 for men); however, sex disparity of RCSM diminished with advancing age (SHR = 1.05 for men). Significant interactions between sex and age groups were found in multivariate models (P < 0.01), on the contrary, OCM remain in favor of female across all age groups. For advanced disease, we observed similar changing trend of RCSM. However, sex disparity of OCM was only found in elderly patients.

Distribution of adjusted SHR of male over female in (A) localized and (B) regional/distant disease.

Each point represents the value of SHR measured with the Fine and Gray competing risks regression models. Bars indicate the 95% CI. Adjusted covariates included year of diagnosis, registry area, marital status, socioeconomic status, race, tumor size, tumor grade, histological type and surgery of primary site. SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Since the observed sex difference in young patients may be related to the presence of unmeasured factors, sensitivity analysis was conducted to estimate their potential effect. We included a dichotomized factor in the multivariate analysis and calculated the minimum magnitude of the unmeasured factor that could alter the conclusions. We found that a factor with at least an SHR of 1.90 (with a female to male prevalence ratio of 9:1) was needed to diminish the prognostic difference by sex (Supplemental Table 2). The magnitude was higher than tumor grade in the same cohort (SHR = 1.79).

Joint effect of age and sex on mortality

Table 2 shows the 5-year mortality rate across all age and sex groups. The 5-year RCSM for localized disease was lowest in young women (2.38%) and increased to 6.58% in older females. The RCSM was quite similar across different age and sex groups for regional/distant disease.

The joint effects of age and sex on cause-specific mortalities, adjusted by the available confounds, are listed in Table 3. Compared with young women, the risk of dying from RCC was higher by at least 63% in the other subgroups for localized disease. In advanced disease, young women did not demonstrate a significantly better RCSM compared with older women and men.

Discussion

The current study confirmed the age-dependent effect of sex on RCSM in localized RCC. Using prespecified age cutoffs, the female advantage in survival was notable in the premenopausal period and was diminished in the postmenopausal period. Joint analyses of age and sex showed that young female patients have the most favorable RCSM among all subgroups. Taken together, our results provide new insight into the contribution of sex to RCC survival. Moreover, the significant survival advantage of young females, even after adjusting for possible confounds, strongly suggests the need to further study the underlying biological mechanisms.

Epidemiological studies of RCC have reported conflicting results about the association between sex and RCSM4,5,6,11,12,13. Some found a significant female advantage, with HRs ranging from 0.75 to 0.815,6,12,13; however, these observations were not repeated in other large studies4,11. Research on other pathophysiological conditions indicates that the estrogen axis is one of the most plausible mechanisms of the female advantage7,14,15,16. Unfortunately, the above-mentioned studies examined the sex effect without considering age-related changes in estrogen levels. A recent study by Rampersaud et al.6, which investigated the effect of age on RCC-specific survival between sexes, reported: (a) that age was an independent predictor of RCC-specific survival in women, but not in men; and (b) that the survival advantage for women was only present in patients younger than 58 years old. These results, for the first time, indicated a different trajectory of age-related mortality between sexes. However, that study did not make in-depth comparisons between sexes across age. The current study, to some extent, overcomes the limitation regarding the sex effect on RCSM. Prespecified age cutoffs divided the patient population into three groups, so that most of the upper and lower tertiary groups were homogeneous in menopausal status. The sex effect was demonstrated using stringent methodology that included multivariate analyses and competing models.

The mechanism of the observed age-sex interaction in localized RCC is still unknown. Based on our findings, we speculate that the survival advantage in young, premenopausal women may be conferred by the estrogen axis. The protective effect of the estrogen axis on survival has been observed in other cancers, such as colorectal cancer17,18. Previous biological research has demonstrated that the estrogen-ERβ axis may play an important role in inhibiting proliferation and inducing apoptosis of RCC cells7. Therefore, a rich circulation of estrogen may enhance the tumor suppressor function of ERβ. Moreover, the expression of ERβ may be different in premenopausal and postmenopausal kidneys. Esqueda et al.19 found that the expression of ERβ was significantly decreased after ovariectomy. Therefore, a synchronized increasing expression of ERβ and estrogen may play a vital role in RCC among premenopausal women.

This study was unable to account for all types of confounds using a population-based database. Some authors have postulated a sex predisposition to hereditary RCC in young patients. However, a reported 5 to 8% incidence would hardly have resulted in the observed sex disparity20. Besides germline alterations, somatic changes were more frequently observed in young subjects. Although RCC associated with Xp11.2 translocation/TFE3 gene fusion has been suggested to account for a substantial amount of RCC at ages < 35, the disease has been more frequently diagnosed in females and has been shown to be associated with poorer outcomes21. Other factors that have been overlooked include screening-related factors and treatment-related mortality. The male:female ratio of prevalence of smaller tumors (≤7 cm) in young patients was 0.99 in the present study, which was comparable with the male:female ratio in older patients (0.97), suggesting that sex differences in cancer screening were minimal. For treatment-related related mortality, we tested the conditional mortality curves for patients who survived more than 1 year after inclusion in the registry. The consistency in the survival advantage excluded the influence of treatment-related short-term mortality on the survival outcome.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the lack of specific indicators of hormonal status, such as information on menopausal status, use of oral contraceptives, or hormone replacement therapy, prohibit a more direct evaluation of their effect and limit our conclusions. Second, comorbidities was not included in multivariate analyses due to comorbidities data on patients younger than 65 years were not available in SEER and linked database. However, our results showed that OCM, a probability intimately related to comorbidities, remain in favor of female in all age groups, which is in contrast to the diminished female advantage in RCSM from premenopausal to postmenopausal period. Another supporting evidence was found in advanced disease: we observed similar trend of RCSM from premenopausal to postmenopausal period, while OCM between sexes was similar in young patients and in favor of female in elderly patients (Figure 2). Therefore, it is highly likely that other age related imbalanced factors account for the changing trend of sex disparity in RCSM. Third, the current study only included patients with de novo advanced RCC. Whether the phenomenon will be attenuated in patients with recurrent systematic disease is an interesting question that warrants further investigation. Finally, there are some uncertainties in the accuracy of ‘SEER cause-specific death classification’ although results from published studies have confirmed the concordance between cause-specific death recorded in SEER database and the underlying cause of death22,23.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings have important implications for better understanding the complex effect of sex on RCSM. These findings may aid in clinical practice by amending prognostic estimation, designing adjuvant trials and planning follow-up. On one hand, considering the joint effect of age and gender on RCSM, physicians could perform more thorough risk assessments and optimize the subsequent treatment. On the other hand, owing to female advantage in survival was notable in the premenopausal period and was diminished in the postmenopausal period, different follow-up strategies should be conducted for different age groups under the circumstance of valid menopausal status is available. In other words, strict follow-up is required for males in younger patients while for both males and females in older patients.

In conclusion, this population-based study confirmed that the sex effect on RCSM was strongly modified by age. Female advantage in RCSM was restrict to premenopausal period for both localized and advanced disease. These findings may aid in clinical practice and need further evaluation of underlying biological mechanisms.

Methods

Study population

The study population was obtained from the November 2012 records of the SEER program of the National Cancer Institute. The SEER database is a large population-based dataset from North America. It covers approximately 28% of the US population and the characteristics of the SEER population are comparable with the general US population, which overcomes the selection bias that commonly exists in published studies. Furthermore, the large size of the database guarantees the statistical power to detect the sex effect.

To retrieve subjects from the SEER database, the following criteria were entered in the selection statement of SEER*stat software: histologically confirmed RCC, excluding cancers diagnosed at autopsy or by death certificate only, RCC recorded as a first primary malignancy, follow-up months more than 0, diagnosed time-frame from 1998 to 2010 and ages 18–90. Of the 125,793 listed cases, we further excluded patients with a tumor size equal to 0 or larger than 30 cm (n = 9558) and SEER historic stage unknown (n = 1696). The study cohort consisted of 114,539 patients with RCC.

Variables assessed

To test the study hypothesis, patients were grouped according to age cutoffs of 42 and 58, which have been shown to be surrogate measures of sex hormone status in multiple epidemiologic studies on menopause in North America. Research has found that more than 95% of women were hormone-intact at age 42, whereas 97% of women had undergone primary ovarian failure by the age of 586,24. Family socioeconomic status (SES) was determined by four variables: median family income, the percentage of individuals living below the poverty line, the percentage of individuals unemployed and the percentage of individuals without a bachelor's degree. Subsequently, we created a combined SES score by summing the standardized scores from these four variables and classified the total scores into high and low SES groups, according to the median25,26. Tumor size was dichotomized by the cutoff of 7 cm. Tumor extent was defined according to SEER historic stages as follows: localized (confined to the kidney), regional (extension into adjacent tissue or lymph node), or distant (metastatic). Variables with missing values were included in the analysis and coded as unknown. The percentage of missing values was highest for tumor grade (30.65%), followed by marital status (3.53%), race (0.53%), registry area (0.17%) and SES (<0.01%). Adjusted covariates included year of diagnosis (1988–2004 vs. 2005–2010), registry area (metropolitan vs. other), marital status (married vs. other), SES (high vs. other), race (white vs. other), tumor size (≤7 cm vs. >7 cm), stage (localized vs. regional/distant), grade (grade III–IV vs. other), histological type (clear cell vs. other) and nephrectomy (yes vs. no).

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome of the current study was cause-specific mortality, which included RCSM and OCM. The cause-specific survival is a net survival measure representing survival of a specified cause of death in the absence of other causes of death. The ‘SEER cause-specific death classification’ variable is used to obtain cause-specific survival probability for a given cohort of cancer patients. Deaths attributed to the cancer of interest are treated as events and deaths from other causes are treated as censored observation (http://seer.cancer.gov/causespecific/). Survival time was defined as the time interval between the date of RCC diagnosis and the recorded date of death or last follow-up, whichever occurred first. Data on vital status, cause of death and survival time were available until November 2012 for all study subjects.

Statistical analyses

To assess the prognostic value of age and sex, we conducted the analyses in the following three steps. First, we used the cumulative incidence function (CIF) to estimate the crude effect of age and sex on RCSM and OCM. Second, the Fine and Gray competing risks regression models were used to examine the effect of sex on cause-specific mortalities stratified by age groups after adjusting for possible confounds. The subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed, with SHR less than 1.00 indicating reduced mortality. Finally, we analyzed the joint effect of age and sex on RCSM. We also assessed the effect required of a hypothetical unmeasured binary factor to explain the observed SHR of sex using sensitivity analysis. All the analyses were stratified by localized disease and regional/distant disease, because OCM makes a substantial contribution to deaths in localized disease, whereas RCSM accounts for the majority of deaths in regional/distant disease.

All statistical analyses were performed with R software using the packages cmprsk, survival and riskRegression27,28,29. The P value was two tailed and was considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

References

Ferlay, J. et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 127, 2893–2917, 10.1002/ijc.25516 (2010).

Siegel, R., Naishadham, D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 63, 11–30, 10.3322/caac.21166 (2013).

Ljungberg, B. et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 60, 615–621, 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.049 (2011).

Aron, M., Nguyen, M. M., Stein, R. J. & Gill, I. S. Impact of gender in renal cell carcinoma: an analysis of the SEER database. Eur Urol 54, 133–140, 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.12.001 (2008).

May, M. et al. Gender differences in clinicopathological features and survival in surgically treated patients with renal cell carcinoma: an analysis of the multicenter CORONA database. World J Urol 31, 1073–1080, 10.1007/s00345-013-1071-x (2013).

Rampersaud, E. N. et al. The effect of gender and age on kidney cancer survival: Younger age is an independent prognostic factor in women with renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol 32, 30 e39–30 e13 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.10.012 (2014).

Yu, C. P. et al. Estrogen inhibits renal cell carcinoma cell progression through estrogen receptor-beta activation. PLoS One 8, e56667, 10.1371/journal.pone.0056667 (2013).

Micheli, A. et al. The advantage of women in cancer survival: an analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Eur J Cancer 45, 1017–1027, 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.008 (2009).

Micheli, A., Mariotto, A., Giorgi Rossi, A., Gatta, G. & Muti, P. The prognostic role of gender in survival of adult cancer patients. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur J Cancer 34, 2271–2278 (1998).

Shahabi, S. et al. Free testosterone drives cancer aggressiveness: evidence from US population studies. PLoS One 8, e61955, 10.1371/journal.pone.0061955 (2013).

Pierorazio, P. M., Murphy, A. M., Benson, M. C. & McKiernan, J. M. Gender discrepancies in the diagnosis of renal cortical tumors. World J Urol 25, 81–85, 10.1007/s00345-006-0124-9 (2007).

Lee, S. et al. Gender-specific clinicopathological features and survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC). BJU Int 110, E28–33, 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10667.x (2012).

Stafford, H. S. et al. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in renal cell carcinoma incidence and survival. J Urol 179, 1704–1708, 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.027 (2008).

Pinton, G. et al. Estrogen receptor-beta affects the prognosis of human malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res 69, 4598–4604, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4523 (2009).

Treeck, O., Lattrich, C., Springwald, A. & Ortmann, O. Estrogen receptor beta exerts growth-inhibitory effects on human mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 120, 557–565, 10.1007/s10549-009-0413-2 (2010).

Hartman, J. et al. Tumor repressive functions of estrogen receptor beta in SW480 colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 69, 6100–6106, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0506 (2009).

Koo, J. H. et al. Improved survival in young women with colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 103, 1488–1495, 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01779.x (2008).

Majek, O. et al. Sex differences in colorectal cancer survival: population-based analysis of 164,996 colorectal cancer patients in Germany. PLoS One 8, e68077, 10.1371/journal.pone.0068077 (2013).

Esqueda, M. E., Craig, T. & Hinojosa-Laborde, C. Effect of ovariectomy on renal estrogen receptor-alpha and estrogen receptor-beta in young salt-sensitive and -resistant rats. Hypertension 50, 768–772, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095265 (2007).

Shuch, B. et al. Defining early-onset kidney cancer: implications for germline and somatic mutation testing and clinical management. J Clin Oncol 32, 431–437, 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.8192 (2014).

Kuroda, N. et al. Review of renal carcinoma associated with Xp11.2 translocations/TFE3 gene fusions with focus on pathobiological aspect. Histol Histopathol 27, 133–140 (2012).

German, R. R. et al. The accuracy of cancer mortality statistics based on death certificates in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol 35, 126–131, 10.1016/j.canep.2010.09.005 (2011).

Hu, C. Y., Xing, Y., Cormier, J. N. & Chang, G. J. Assessing the utility of cancer-registry-processed cause of death in calculating cancer-specific survival. Cancer 119, 1900–1907, 10.1002/cncr.27968 (2013).

McKinlay, S. M. The normal menopause transition: an overview. Maturitas 23, 137–145 (1996).

Sun, M. et al. A non-cancer-related survival benefit is associated with partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol 61, 725–731, 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.047 (2012).

White, A., Coker, A. L., Du, X. L., Eggleston, K. S. & Williams, M. Racial/ethnic disparities in survival among men diagnosed with prostate cancer in Texas. Cancer 117, 1080–1088, 10.1002/cncr.25671 (2011).

Baxi, S. S. et al. Causes of death in long-term survivors of head and neck cancer. Cancer 120, 1507–1513, 10.1002/cncr.28588 (2014).

Teixeira, L., Rodrigues, A., Carvalho, M. J., Cabrita, A. & Mendonca, D. Modelling competing risks in nephrology research: an example in peritoneal dialysis. BMC Nephrol 14, 110, 10.1186/1471-2369-14-110 (2013).

Noordzij, M. et al. When do we ompeting risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant 28, 2670–2677, 10.1093/ndt/gft355 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by grants from the Shanghai leaders' foundation and the Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81001131, 81370073 and 81202004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. and Y.Z. acquired the data and drafted the manuscript, Y.Q. and H.Z. analyzed and interpreted the data, H.C. and J.X. prepared all figures, W.G. and C.G. edited all tables, D.Y. and Y.Z. designed the study. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplemental Figure and Table

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, Y., Chen, H., Gu, W. et al. Age-Dependent Association between Sex and Renal Cell Carcinoma Mortality: a Population-Based Analysis. Sci Rep 5, 9160 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09160

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09160

This article is cited by

-

CT differentiation of fat-poor angiomyolipomas from papillary renal cell carcinomas: development of a predictive model

Abdominal Radiology (2021)

-

Sex-specific hormone changes during immunotherapy and its influence on survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy (2021)

-

Phosphorylated 4EBP1 is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Age-specific cancer mortality trends in 16 countries

International Journal of Public Health (2016)

-

DNA repair system and renal cell carcinoma prognosis: under the influence of NBS1

Medical Oncology (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.