Abstract

We report a detailed experimental study of the complex behavior of a dc low-pressure plasma discharge tube of the type commonly used in commercial illuminated signs, in a microfluidic chip recently proposed for visible analog computing and other practical devices. Our experiments reveal a clear quasiperiodicity route to chaos, the two competing frequencies being the relaxation frequency and the plasma eigenfrequency. Based on an experimental volt-ampere characterization of the discharge, we propose a macroscopic model of the current flowing in the plasma. The model, governed by four autonomous ordinary differential equations, is used to compute stability diagrams for periodic oscillations of arbitrary period in the control parameter space of the discharge. Such diagrams show self-pulsations to emerge remarkably organized into intricate mosaics of stability phases with extended regions of multistability (overlap). Specific mosaics are predicted for the four dynamical variables of the discharge. Their experimental observation is an open challenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An outstanding problem is to understand and control the complex chaotic behaviors commonly observed in glow discharge plasma tubes. From an experimental point of view, the first observations of deterministic chaos1, mixed-mode oscillations and homoclinic chaos in discharge tubes2 date back more than twenty years ago. Currently, much attention has been focused on the generic problem of phase synchronization using these devices. In particular, phase synchronization has been demonstrated under different conditions3,4,5. More recently, the transition to chaos and constructive effects of noise, such as stochastic resonance and coherence resonance, have been reported in plasma tubes6,7,8,9. All aforementioned works have in common the feature of using discharge tubes specifically built for research: Geissler's tubes, Plücker's tubes and so on. Conversely, in this work, we present an application of nonlinear dynamics to study the behavior of a popular device not designed specifically for research purposes. Due to the great impact of plasma as a component in modern image viewing devices, the investigation of plasma tubes is of considerable interest. Additional applications of interest involve microfluidic chips proposed for visible analog computing10 and the ability of glow discharges to find the shortest way through a maze11.

Electrical discharges have been continuously the subject of innumerous works and much is known about them12,13,14,15,16. From a theoretical point of view, discharges have been traditionally described taking into account the complex processes involved in the plasma recombination and electric conductivity. Such descriptions require the use of coupled partial differential equations involving spatial and time variables, the transport of momentum and energy of plasma components, the continuity equation, diffusion equation, Poisson equation, etc. This means that a realistic description is generally quite involved. However, a fair description of the discharge can be obtained by bypassing most of the aforementioned complexities and focusing solely on the key feature, namely the discharge capacity of conducting electric current. In other words, one may consider a macroscopic volt-ampere characterization of the discharge, regarding then the whole plasma simply as a nonlinear two-terminal component of an electric circuit. Clearly, such approach removes spatial dependencies and reduces the mathematical description to a nonlinear set of coupled ordinary differential equations, a more easy problem to deal with. The quality of this approach, of course, is proportional to the quality of the volt-ampere characterization of the plasma tube.

In this work we explore the dynamical behavior of the plasma tube in the region of glow discharge. We present a phenomenological model based on the macroscopic electrical features, leading to a two-dimensional nonlinear model. Additional considerations, related to the experimental observation of chaos, induce us to introduce additional degrees of freedom. We then check experimentally and through numerical simulations that our model gives a fair representation of the discharge. Finally, we use the model to predict the distribution of self-pulsations in the control parameter space of the discharge. Before proceeding, we stress the fact that although our model is able to explain a number of experimentally measured features of the discharge, it is just a rough approximation of the complex spatial processes underlying the plasma. Over the years, there have been numerous attempts of modeling plasma discharges as circuits. Such models, however, aim to reproduce the plasma with a much higher accuracy than is needed here. For instance, instead of ordinary differential equations, more detailed models normally involve partial differential equations. Detailed references about generation of low- and high-energy plasmas can be obtained, e.g., in the several specialized books12,13,14,15,16.

Results

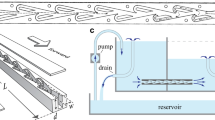

The object of our investigations is a plasma tube device of the type commonly used in commercial neon signs and other applications10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The tube is filled with neon at a low-pressure of the order of a few Torr and has a length of 50 cm and 2.5 cm of diameter. Both electrodes are identical and can be used as anode or cathode indifferently. The experimental setup is sketched in Fig. 1.

An adjustable high-voltage dc source Vbias (Fluke 415B) allows us to excite and drive the tube in the glow discharge operating region. The Vbias plays the role of control parameter. Here, Rb and Rl are a 150 kΩ ballast resistor and a 1 kΩ load resistor (nominal values), respectively. The capacitor C (2.4 nF), in parallel to the tube, makes the circuit behave as an electrical relaxation oscillator. With this setup, we performed preliminary measurements to determine the electrical nonlinear characteristic of the tube. More explicitly, we measured the voltage drop vl through Rl (using an Agilent 34401A multimeter) corresponding to several Vbias values. From these data we calculated the discharge voltage across the tube (vt in our equations) and reconstructed the electrical volt-ampere characteristic curve using the following equation

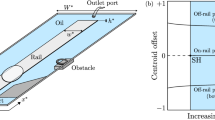

The experimental data are plotted in Fig. 2 where we use the total current i instead of i2, supposing that the current through Rl and the tube are the same. The obtained volt-ampere characteristic curve has a negative slope and is in good agreement with neon lamp curves found in literature13.

The range of interest for Vbias, corresponding to the data over the maximum peak plotted in Fig. 2, is 730 V < Vbias < 2000 V. In this operating region we studied the dynamical behavior of the plasma tube. Two distinct signals were experimentally acquired: the discharge voltage across the tube together with the corresponding light emission. A probe ×10 and a photodiode (New Focus 1621, not shown in Fig.1) were used. Both voltage signals were recorded with a digital oscilloscope (LeCroy LT342).

The recorded temporal sequences were used to construct bifurcation diagrams. Fixing C = 2.4 nF, Fig. 3(a) shows a bifurcation diagram where the maxima of the voltage signal are plotted versus the control parameter Vbias and Fig. 3(b) shows a zoom of the range 730 V < Vbias < 900 V. This diagram hints to the presence of a sub-harmonic transition to chaos. Figure 3 (c) shows a return map, namely a plot of successive pairs of maxima of the signal. This return map illustrates a typical period-2 oscillation. Then, by increasing Vbias, one observes a period-4 oscillation and another period-2 oscillation (see Figs. 3(d) and 3(e)), before and after an interior crisis characterized by a sudden decrease in the relative amplitude of the voltage signal (see Fig. 3(a) around 1350 V). Lastly, Fig. 3 (f), shows a structure resembling somewhat the familiar Hénon chaotic attractor.

Experimental measurements for C = 2.4 nF showing a peak-doubling route to chaos in the discharge.

(a) Bifurcation diagram. (b) Enlargement of the leftmost portion of (a). The blue arrows in (a) indicate the values of Vbias where the following return maps were measured: (c) 1000 V; (d) 1320 V; (e) 1400 V; (f) 1550 V.

Investigating the Vbias range 730 V–900 V allows us to localize a period-one solution at Vbias = 730 V. Here a limit cycle at a frequency of 670 Hz is observed suggesting that we deal with a stationary regime of the plasma characterized only by the frequency of the relaxation oscillator imposed by the capacitor C. In absence of the capacitor C, as in Ref. (6), the plasma is in a homogeneous state. In fact, a slightly increase of Vbias leads to period-two solutions and to a narrow chaotic region. As an example, at Vbias = 750 V, the corresponding power spectrum reveals a dominant peak at 890 Hz, its near subharmonic at 450 Hz and a weak remnant peak at 670 Hz. This suggest that a two frequency route to chaos or quasiperiodicy scenario is encountered. The second frequency, competing with the relaxation frequency, is peculiar of the investigated plasma. The nature of transition to chaos was more clearly manifested when decreasing the dissipativity, i.e. when the capacitor value is increased from C = 2.4 nF to C = 4.8 nF. As can be seen in Fig. 4, in this case the discharge displays an elusive quasi-periodicity route to chaos, a scenario which is corroborated by a careful analysis of a torus breaking phenomenon. The bifurcation diagram in Fig. 4 (a) is markedly different from the one in Fig. 3 (a). The Poincaré sections indicate a transition from a limit cycle (Fig. 4 (c)) to a two dimensional torus (Fig. 4 (d)), as characterized by the closed loop section. A further increase of the control parameter leads to a torus breaking (Fig. 4 (e)) and, successively, to a condition of developed chaos (Fig. 4 (f)).

Experimental measurements for C = 4.8 nF evidencing a quasiperiodicity route to chaos.

(a) Bifurcation diagram. (b) Enlargement of the leftmost portion of (a). The blue arrows in (a) indicate the values of Vbias where the following return maps were measured: (c) 1100 V; (d) 1160 V; (e) 1180 V; (f) 1200 V.

The temporal behavior and magnitude spectrum associated to the quasiperiodic doubling cascade obtained at C = 2.4 nF and Vbias = 1000 V are reported in Fig. 5(a) and 5(b) respectively. Fig. 5(b) clearly displays two peaks, the lower one (plasma eigenfrequency) not being a subharmonic of the relaxation frequency at f = 1610 Hz. Fig. 5(c) and 5(d) display the behavior of the relaxation frequency and plasma eigenfrequency as a function of Vbias for C = 2.4 nF and C = 4.8 nF, respectively. In the first case (Fig. 5 (c)), their ratio (feig/fmod) is near 0.5 while in the second case (Fig. 5(d)) is near 0.89.

We now derive experimentally a macroscopic model of the nonlinear behavior of the plasma discharge. The starting point are Kirchhoff's laws applied to the electrical circuit of Fig. 1. Denoting by vt and i2 the discharge voltage and the current through the tube, respectively, it is not difficult to derive the following equations

where we disregarded a term containing Rl because  . The last two equations yield

. The last two equations yield

An additional equation governs the voltage drop on the loop

where we introduced the spurious inductance L of the tube and its voltage-current characteristic G(i2).

The nonlinear function G(i2) is determined experimentally by measuring voltage drop vl through Rl (see Fig. 1) and calculating vt from Eq. (1). In order to obtain a dimension-less form of the previous equations we make the following simplifying assumptions. The experimental electrical characteristics reaches an asymptotic value of about v = 360 V on the right border of the normal glow region, we use this value to rescale our equations and to define the first two dimensionless quantities y and g (hereafter, dropping the subscript, we replace i2 by i)

Since the order of magnitude of the current i is 10−3 A, we introduce a convenient scale factor α = 10−3 A and a dimensionless variable x such that

As shown in Fig. 5(a), observing the temporal sequences we can note that the interspikes interval between two successive peaks is almost invariant with respect to our control parameter Vbias and that it assumes the value of about β1 = 0.5 · 10−3 s. We use this value to introduce the dimensionless time variable t → β1 · t (maintaining the same symbol t). Using two additional definitions, Vbias ≡ v · yo and β2 ≡ RbC, from Eq. (5) we obtain

where we used the abbreviations A0 = yoβ1/β2, A1 = β1/β2 and A2 = A1Rbα/v.Similar arguments allows us to rewrite Eq. (6) as

where the parameter μ = (α · L)/(v · β1) is connected to the spurious inductance L which cannot be bypassed experimentally.

We assume for G(i) = v · g(i) a simple mathematical form accounting for the two regions of the characteristic curve, namely

redefining k1 = K1 · α and k2 = K2 · α we arrive at the following dimensionless form

The values of the parameters yc, a, k1 and k2 are obtained by fitting the experimental data (Fig. 2). Such fits give yc = 0.977, a = 0.9425, k1 = 0.4662, k2 = 26.1, with the quality coefficient of fit being  , indicating a quite good fit to the data17.

, indicating a quite good fit to the data17.

Experimentally we observe some windows of chaotic behavior. Since the Poincaré–Bendixson theorem forbids chaos in two-dimensional systems (such the relaxation oscillator described by Eqs. (15) and (16)), to be able to describe the experimental results we need extend the dimensionality of the model by introducing additional degrees of freedom related to the plasma eigenfrequencies. Observing the temporal sequences, we note that in chaotic regime the spikes amplitudes change significantly, in an oscillatory way, but their interspikes intervals are unchanged. This behavior can be reproduced by the following damped oscillator

This plasma oscillation is driven by the current and it is rapidly damped when the current decreases to zero. We suggest an oscillatory modulation around the working point to reproduce the experimental time series. In this case, the new electrical characteristic is

where we fix the parameters yc = 1, a = 1, k1 = 0.5 and k2 = 26.

With this, our macroscopic model of the discharge tube is now complete:

The parameters A0, A1, A2 are related to the experimental configuration adopted. Namely, A0 is connected to the bias voltage, plays the role of control parameter and varies in the range [3, 7.8]. Parameters A1, A2 depend of the capacitor contained in the electrical circuit, while μ, β, ω and γ are free parameters. Concerning the parameter μ, we add the following. Since α = 10−3 A, v = 360 V and β1 = 0.5 · 10−3 s, from the definition of μ in Eq. 8 we get

Since it is highly unlikely to have spurious inductances L of the order of 1 H, one sees that μ is lower than 10−3. Note, however, that μ can be used to externally control a time-scale of the circuit.

Discussion

The experimentally derived macroscopic model in Eqs. (13)–(16) can be used to predict numerically the distribution of stable self-generated complex oscillatory patterns in the discharge. Such study serves a few good purposes. On one hand, one may derive a wide-ranging phase diagrams providing a systematic classification of the oscillatory states, of their relative abundance and of the boundary separating oscillatory phases. Since it is much harder to perform real-life experiments over extended parameter domains than computer simulations, numerically obtained phase diagrams allow experiments to be planed and performed for more promising parameter regions in control space. The availability of numerical predictions provides data against which to compare the reliability of the theoretical description and to improve it where needed.

Using the model in Eqs. (13)–(16) we computed the bifurcation diagram shown in Fig. 6 (a) and three return maps as indicated in the figure. These plots should be compared with the corresponding ones seen in Fig. 3. Note the larger interval of A0 in Fig. 6 (a). As one sees, while there is a fair overall agreement between Fig. 3 and 6, the bifurcations seen for higher values of A0 in Fig. 3 (a) display a reverse doubling scenario which is not seen in Fig. 6. This means that the agreement between measurements and modeling deteriorates as A0 increases. We have also attempted to locate an adequate region of the model to reproduce unambiguously the quasiperiodicity route observed experimentally. While the model can provide signs of quasiperiodicity, clear evidence could not be found.

Bifurcation diagram of local maxima of x for γ = 5 with ω varying in the interval ω ∈ [6, 7].

Only maxima of x greater than 30 were included. Resolution: 600 × 600. Return maps x(tmax) × x(tmax+ 1) corresponding to the values of A0 indicated by the blue lines in the bifurcation diagram, namely (A0, ω) = (4.522, 6.217), (5.622, 6.375), (6.161, 6.452).

Our model was also used to compute the isospike diagrams18,19,20,21,22 shown in the four panels of Fig. 7, i.e. phase diagrams depicting for every point in control parameter space the number of spikes contained in one period of the regular oscillations. The colors of the individual panels depict the number of spikes contained in one period of the stable oscillation of each of the four variables x, y, z, w, as indicated in the figure caption. Black represents “chaos”, i.e. parameters for which it was not possible to detect any periodicity. Specific details about how these stability diagrams were computed are given below in the Computational Methods.

The stability diagrams in Fig. 7 allow one to recognize the rich and intricate interplay between the continuous spike-adding and spike-doubling mechanisms responsible for the complexification of periodic oscillation of the electric discharge. Each variable produces a complex mosaic of colors, showing how the number of spikes self-organize in control space. A significant feature in Fig. 7 is that, although all phase diagrams display the same structure, independently of the variable used to construct them, the individual phases vary in a way that is quite hard to summarize in any means other that by displaying them graphically.

Figure 8 shows bifurcation diagrams for the four variables of the model, computed by varying two parameters simultaneously along the diagonal straight line segments shown in Fig. 7. While the overall structure of the diagrams is essentially the same, independent of the variable used to count spikes, the number of spikes in the several branches changes considerably, corroborating the sequences recorded in the stability diagram of Fig. 7. Noteworthy are the many jumps observed in the bifurcation diagrams, which signal abundance of multistability in the region, i.e. the possibility of stabilizing distinct attractors according to the initial conditions used. This behavior stresses the richness of the dynamical states supported by the discharge.

Bifurcation diagrams obtained when varying two parameters simultaneously along the white lines shown in the panels of Fig. 7.

Individual panels display 600 × 600 parameter points. Apparently, the discharge is trying to imitate Magrite's Golconde, demonstrating the fine line between individuality and group association and how it is blurred, as in labyrinth bifurcations [25].

In this paper, we reported an experimental study of a low-pressure electrical discharge recording for it the standard doubling scenario as well as a remarkable elusive route to chaos by quasiperiodicity. By characterizing the discharge through a volt-ampere characteristic, we developed a simple model reproducing its basic features. Based on this model, we performed a detailed classification of the oscillatory behaviors, periodic or not, supported by the discharge. By computing stability diagrams for all model variables, we characterized both the size and shape and the unexpected sequential ordering underlying the organization of stability phases. Our diagrams show precisely where the number of spikes changes as a function of the variables used to count them. We found a plethora of stability islands which are simply too complicated to be classified systematically or to be described by other means than purely graphically. Incidentally, we mention that currently there is no method to locate analytically stability phases for nonlinear oscillations of arbitrary periods so that the only way to find them is through direct numerical computations. Note that the information in our phase diagrams allows one to effectively control the dynamics, namely to select the final dynamical state precisely by performing just a single change of parameters. This is in sharp contrast with conventional methods of controlling the dynamics23,24, which require pre-investigating unstable orbits, do not include a prescription for the precise selection (targeting) of the final state and require the permanent application of external perturbations.

In summary, although relatively simple, the macroscopic discharge model reported here can reproduce basic experimental observations and reveals rich and unexpected dynamical facts. Future work should tell if the complex stability mosaics predicted by this model can be also found in experimental diagrams or in predictions derived taking into account spatial phenomena of the discharge as described, e.g. by more sophisticated discharge models based on sets of partial differential equations.

Methods

Computational methods: The isospike diagrams18,19,20,21,22 in Fig. 7 were obtained by solving the model equations numerically for the following set of parameters: μ = 3 × 10−4, β = 8 × 10−3, γ = 4.2, A1 = 1.4 and A2 = 0.6, where the last two values refer to C = 2.4 nF. To this end, we used the standard fourth-order Runge-Kutta algorithm with fixed-step, h = 5 × 10−6, over a mesh of 400 × 400 equally spaced points. For each value of ω, we started the numerical integrations at A0 = 3 from the arbitrarily chosen initial condition (x, y, z, w) = (1, 1, 0.01, 0.01) and then proceed by following the attractor, using the last obtained values of the variables to start every new integration involving infinitesimal changes of parameters. The first 400 × 106 time-steps were discarded as transient time needed to reach the final attractor. The subsequent 100 × 106 iterations were then used to compute the number of spikes contained in one period of the oscillations, by recording up to 800 extrema (maxima and minima) of the time series of the variable under consideration, together with the instant when they occur and recording repetitions of the maxima. As indicated by the colorbar in the figures, a palette containing 17 colors was used to represent “modulo 17” (i.e. recycling colors) the number of peaks (maxima) contained in one period of the oscillations. The computation of stability diagrams is numerically a quite demanding task that we performed with the help of 1536 processors of a SGI Altix cluster having a theoretical peak performance of 16 Tflops. While it is possible to observe period-doubling routes, most of the times what happens is just the addition of a new peak to the waveform (without a corresponding doubling the period). Eventually, after adding several peaks, one reaches a situation where the period roughly doubles a previously observed value.

The bifurcation diagrams in Fig. 8 were obtained by plotting the local maximum values (spikes) of the four variables along the lines shown in the four panels of Fig. 7, namely when tuning A0 and ω simultaneously along the line ω = 1.222A0 – 0.844. In all diagrams, both axis were divided into 600 equally spaced values. As done for the stability diagrams, computations were started at the minimum value of A0 from the initial condition (x, y, z, w) = (1, 1, 0.01, 0.01) and continued by following the attractor using the same integrator and integration step. The first 16 × 106 steps were discarded as transient, while during the subsequent 4 × 106 steps plotting no more than 200 spikes (local maxima) of the variable under consideration.

References

Braun, T., Lisboa, J. A., Francke, R. E. & Gallas, J. A. C. Observation of deterministic chaos in electrical discharges in gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 613–616 (1987).

Braun, T., Lisboa, J. A. & Gallas, J. A. C. Evidence of homoclinic chaos in the plasma of a glow discharge. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 2770–2773 (1992).

Rosa, E., Pardo, W., Ticos, C. M., Walkenstein, J. A. & Monti, M. Phase synchronization of chaos in a discharge tube. Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos 10, 2551–2564 (2000).

Ticos, C. M., Rosa, E., Pardo, W., Walkenstein, J. A. & Monti, M. Experimental real-time phase synchronization of a paced chaotic plasma discharge. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2929–2932 (2000).

Davis, M. S., Nutter, N. G. & Rosa, E. Driving phase synchronous plasma discharges with superimposed signals. Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos 17, 3513–3518 (2007).

Dinklage, A., Wilke, C., Bonhomme, G. & Atipo, A. Internally driven spatiotemporal irregularity in a dc glow discharge. Phys. Rev. E 62, 042702 (2001).

Letellier, C., Dinklage, A., El-Naggar, H., Wilke, C. & Bonhomme, G. Experimental evidence for a torus breakdown in a glow discharge. Phys. Rev. E 63, 7219–7226 (2000).

Nurujjaman, M., Iyengar, A. N. S. & Parmananda, P. Noise-invoked resonances near a homoclinic bifurcation in the glow discharge plasma. Phys. Rev. E 78, 026406 (2008).

Nurujjaman, M., Narayanan, R. & Iyengar, A. N. S. Parametric investigation of non-linear fluctuations in a dc glow discharge plasma. Chaos 17, 043121 (2007).

Reyes, D. R., Ghanem, M. M., Whitesides, G. M. & Manz, A. Glow discharge in microfluidic chips for visible analog computing. Lab on a Chip 2, 113–116 (2002).

Dubinov, A. E., Maksimov, A. N., Minorenko, M. S., Pylayev, N. A. & Selemir, V. D. Glow discharge based device for solving mazes. Phys. Plasma 21, 093503 (2014).

Piel, A. Plasma Physics (Springer, Berlin, 2010).

Roth, J. R. Industrial Plasma Engineering. Volume 1: Principles (Institute of Physics Publishing, London, UK, 1995).

Liebermann, M. A. & Lichtenberg, A. J. Principles of Plasma Discharges and Material Processing (Wiley, New York, 1994).

Raizer, Y. P. Gas Discharge Physics (Springer, Berlin, 1991).

Chapman, B. Glow Discharge Processes (Wiley, New York, 1980).

Björck, A. Numerical Methods for Least Squares Problems (SIAM, Philadelphia, 1996).

Freire, J. G. & Gallas, J. A. C. Stern-Brocot trees in the periodicity of mixed-mode oscillations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 12191–12198 (2011).

Freire, J. G. & Gallas, J. A. C. Stern-Brocot trees in cascades of mixed-mode oscillations and canards in the extended Bonhoeffer-van der Pol and the FitzHugh-Nagumo models of excitable systems. Phys. Lett. A 375, 1097–1103 (2011).

Freire, J. G., Pöschel, T. & Gallas, J. A. C. Stern-Brocot trees in spiking and bursting of sigmoidal maps. Europhys. Lett. 100, 48002 (2012).

Souza, S. L. T., Lima, A. A., Caldas, I. R., Medrano-T, R. O. & Guimarães-Filho, Z. O. Self-similarities of periodic structures for a discrete model of a two-gene system. Phys. Lett. A 376, 1290–1294 (2012).

Hoff, A., da Silva, D. T., Manchein, C. & Albuquerque, H. A. Bifurcation structures in a four-dimensional Chua model. Phys. Lett. A 378, 171–177 (2014).

Handbook of Chaos Control Schöll, E. & Schuster, H. G. (eds.), (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2007).

Fradkov, A. L. & Pogromsky, A. Yu. Introduction to Control of Oscillations and Chaos (World Scientific, Singapore, 1999).

Kovanis, V., Gavrielides, A. & Gallas, J. A. C. Labyrinth bifurcations in optically injected diode lasers. Eur. Phys. J. D 58, 181–186 (2010).

Acknowledgements

E.P. and R.M. thank Professor F.T. Arecchi for many discussions during this work. They also thank K.G. Mishagin, O. Kanakov and K. Al-Naimee for helpful discussions during the early stage of the experiment and its modelization and Fondazione Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze for financial support. J.G.F. was supported by the Post-Doctoral grant SFRH/BPD/43608/2008 from FCT, Portugal. J.A.C.G. thanks support from CNPq, Brazil. All bitmaps were computed at the CESUP-UFRGS clusters, in Porto Alegre, Brazil. This work was supported by the Max-Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems, Dresden, in the framework of the Advanced Study Group on Optical Rare Events.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.P. and R.M. conceived the experiments. E.P. and S.E. performed the experiments. J.G.F. and J.A.C.G. performed the simulations. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pugliese, E., Meucci, R., Euzzor, S. et al. Complex dynamics of a dc glow discharge tube: Experimental modeling and stability diagrams. Sci Rep 5, 8447 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08447

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08447

This article is cited by

-

Unraveling the dynamics of Lorentzian excitations in an ultra-relativistic degenerate plasma

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2024)

-

Effects of noise on the internal resonance of a nonlinear oscillator

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Periodicity hubs and spirals in an electrochemical oscillator

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.