Abstract

Organic batteries free of toxic metal species could lead to a new generation of consumer energy storage devices that are safe and environmentally benign. However, the conventional organic electrodes remain problematic because of their structural instability, slow ion-diffusion dynamics and poor electrical conductivity. Here, we report on the development of a redox-active, crystalline, mesoporous covalent organic framework (COF) on carbon nanotubes for use as electrodes; the electrode stability is enhanced by the covalent network, the ion transport is facilitated by the open meso-channels and the electron conductivity is boosted by the carbon nanotube wires. These effects work synergistically for the storage of energy and provide lithium-ion batteries with high efficiency, robust cycle stability and high rate capability. Our results suggest that redox-active COFs on conducting carbons could serve as a unique platform for energy storage and may facilitate the design of new organic electrodes for high-performance and environmentally benign battery devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of lithium-ion batteries to store energy and supply power has attracted widespread interest owing to their considerable success in portable electronics and their promising prospects for accelerating the development of electric vehicles1. Commercially available lithium-ion batteries largely rely on transition metal oxide cathodes that consist of transition metal elements such as cobalt, iron, nickel and manganese, which cause serious environmental concerns with respect to pollution and require tedious and expensive post-treatment processes for disposal and recycling. Transition metal oxide electrodes easily undergo exothermal reactions when overcharged, which is a potential safety hazard. From the perspective of sustainable development, efficient and environmentally benign cathode materials are highly desirable. Organic cathode materials are promising candidates to replace transition metal oxide cathodes1,2,3,4,5,6 because they are free of transition metal species and their operation is based on the redox reactions of organic units to store energy. Although promising, as documented by many organic electrode materials including small organic compounds7,8, conductive polymers9, polyradicals2, polycarbonyls10,11 and other polymers12, energy storage using these conventional organic electrodes suffers from many drawbacks4,5, including the following issues: (i) the dissolution of redox-active species into electrolytes, which leads to a deterioration in stability and efficiency; (ii) restricted electrolyte ion mobility in the electrodes, which lowers the efficiency; and (iii) poor conductivity, which limits the rate performance. The slow diffusion of electrolyte ions and low electrical conductivity are also general issues for transition metal oxide cathodes13,14.

Ordered porous organic frameworks have substantial advantages for use as potential electrode materials because they offer robust networks that enhance stability and provide open pores that facilitate the transport of electrolyte ions. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are a class of crystalline porous polymers with an atomically precise integration of building blocks into a two- or three-dimensional topology15,16 characterised by lightweight elements and strong covalent bonds. COFs are predesignable porous network polymers with a built-in π-array and ordered one-dimensional channels and these materials have emerged as a new platform for designing a wide variety of functional materials for gas adsorption15,16,17,18, catalysis19,20, pseudocapacitors21, proton conduction22 and semiconductors23,24,25,26. However, the robust porous structures of COFs have not been utilised as cathode materials and their potential for energy storage in lithium-ion batteries has not yet been explored.

Here, we report on the development of a crystalline, mesoporous and redox-active COF on carbon nanotube (CNT) wires as a new platform for energy storage. The interwoven COF is insoluble, which provides the electrodes with robust structural stability. The open channel walls of the COFs are redox active and readily accessible to the electrolyte ions, whereas the aligned mesoporous channels facilitate the transport of electrolyte ions into and out of the electrode, thereby accelerating the electrochemical redox reactions. The electron mobility is greatly improved by growing the COFs on CNTs and the open porous structures of the CNTs also facilitate the transport of ions to the reaction sites. The synergistic combination of these structural features and properties in one material results in the COF-based cathodes that efficiently utilise the redox-active units, exhibit robust cycle stability and enable high-rate energy storage and power supply.

Results

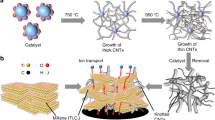

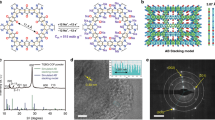

The redox-active COF (Figure 1, DTP-ANDI-COF) is a crystalline mesoporous polymer that contains redox-active naphthalene diimide walls (Figure 1a–c)27 and the triphenylene knots and boronate linkages are electrochemically inactive. The in situ polycondensation of DTP-ANDI-COF on CNT wires under solvothermal conditions generated DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs (Figure 1e), which exhibited strong X-ray diffraction (XRD) peaks at 1.94, 3.42, 3.96, 5.26, 6.88, 7.70, 8.72 and 25.3° that were assigned to the (100), (110,) (200), (300), (400), (500), (600) and (001) facets of DTP-ANDI-COF, respectively (Figure 2a). These structural signals are identical to those of DTP-ANDI-COF prepared in the bulk state (Figure S1a, b)27, indicating that the crystal structure of the AA stacking lattice and the ordered mesoporous channels of DTP-ANDI-COF are retained in the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area and pore volume of DTP-ANDI-COF in DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs were calculated to be as high as 676 m2 g−1 and 0.78 cm3 g−1, respectively (Figure 2b, c). Calculations of the pore size distribution profiles using the nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) revealed the presence of only one type of 5.06-nm-wide mesopores that accounts for the porosity (Figure 2c)28. The pore size was the same as that of DTP-ANDI-COF (Figure S1c, d). The large surface area was attributed to DTP-ANDI-COF and the contribution from the CNTs was considered negligible (only 9 m2 g−1 for CNTs; Figure S2). Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) revealed that the CNTs were covered by the DTP-ANDI-COF and that some DTP-ANDI-COF particles protruded from the surface (Figure 2d–h). These results suggest that DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs consists of crystalline mesoporous COFs grown on the conducting CNT wires.

Structure of redox-active organic electrode materials.

(a), Schematic of the AA-stacking of DTP-ANDI-COF with redox-active naphthalene diimide walls (red) and one-dimensional meso-scale channels. (b), Chemical structure of one pore in DTP-ANDI-COF. (c), Electrochemical redox reaction of a naphthalene diimide unit. (d), Photographs of a coin-type battery. (e), Graphical representation of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs (grey for CNTs) and electron conduction and ion transport.

Characterisations.

(a), XRD profile. (b), Nitrogen sorption isotherms measured at 77 K. (c), Pore-size distribution and cumulative pore volume profiles calculated using NLDFT. (d), FE-SEM image. The CNT wires were covered by DTP-ANDI-COFs and some of the DTP-ANDI-COFs protruded from the CNT wires. (e)–(h), HR-TEM images at different magnifications ((e), A large-area image of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs. (f), An enlarged image of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs. (g), An HR image of the DTP-ANDI-COFs on CNTs. (h), An HR-TEM image of the contact between the DTP-ANDI-COFs and CNTs.

Naphthalene diimide (NDINA, Figure S3a) undergoes a reversible two-electron redox reaction during lithiation and delithiation through an enolisation mechanism (Figure 1c)7,10, as revealed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements (Figure S3b) of lithium-ion batteries using NDINA cathodes with LiPF6 as the electrolyte in a mixture of ethylene carbonate and dimethyl carbonate (1/1 by weight; for battery fabrication, see the Supplementary Information, SI). Under a relatively high current density of 200 mA g−1, the initial discharge capacity was 7.9 mAh g−1 (Figure S3c), which corresponds to the use of 10% of the imide groups in the cathodes for energy storage. As the charge-discharge cycle was repeatedly applied, the discharge capacity continuously decreased and did not reach a stable value (Figure S3c, d); after 50 cycles, the capacity decreased to 4.1 mAh g−1, which corresponds to an efficiency of approximately 4% of the total redox-active imide units in the electrodes. The low efficiency in utilising the redox-active units and the trend of decreasing capacity upon cycling have been observed for many organic electrode materials3,4,5,7. The electrode materials easily dissolve in the electrolytes during the charge and discharge processes and have limited porosity for transporting electrolyte ions to the redox-active centres. These features indicate that NDINA itself is redox active but does not function adequately as a cathode material.

When naphthalene diimide units were integrated into the crystalline mesoporous frameworks of DTP-ANDI-COF, the efficiency in utilising the redox-active units was increased. The initial discharge capacity was 42 mAh g−1 (Figure S4a), which corresponds to a 48% efficiency under a current density of 200 mA g−1. The capacity plateaued at 21 mAh g−1 after 30 cycles (Figure S4a), which corresponds to a 26% efficiency. The enhanced efficiency of the DTP-ANDI-COF cathodes originates from their stable frameworks, which cannot dissolve in electrolytes (Figure S1b), along with their high porosity (Figure S1c, d; BET surface area = 1583 m2 g−1, pore size = 5.06 nm), which facilitates ion transport29,30. The electrochemical impedance spectrum (EIS) exhibited a distorted semicircle in the relatively high-frequency region (Figure 3a, dotted black curve). Equivalent circuit simulations (Figure S5b) revealed that the DTP-ANDI-COF cathodes had a charge transfer resistance as large as 129 ohms (Table S1)9,11,31. This high resistance results in a low efficiency in utilising the redox-active units.

Resistance and redox activity.

(a), Electrochemical impedance spectra in the form of a Nyquist plot of the DTP-ANDI-COF (dotted black curve) and DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs (red curve) batteries tested from 10 kHz to 10 mHz. (b), CV curves of the DTP-ANDI-COF (black curve), DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs (red curve) and COF-5 (dotted black curve) batteries tested at 0.5 mV s−1.

Based on the above results, we produced electrodes by growing DTP-ANDI-COF on conductive CNT wires in situ, which serve as an electron conductors (Figure 1e). In the CV profiles, the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs (Figure 3b, red curve) retain the basic feature of DTP-ANDI-COF (black curve), which indicates that the two-electron involved redox activity of the NDINA units is retained. The polarisation, which is defined as the gap between the oxidation potential and the first reduction potential, provides information on the conductivity. The DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs exhibited a polarisation value of 0.19 V, which is considerably smaller than that (0.29 V) of DTP-ANDI-COF (Figure 3b). This result indicates that the conductivity of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs is significantly increased. Indeed, the EIS profile (Figure 3a, red curve) exhibits a very small semicircle and the equivalent circuit simulations (Figure S5a) revealed that the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs possessed a decreased resistance of only 8.5 ohms (Table S1), which is considerably smaller than that of DTP-ANDI-COF (129 ohms). The negligible difference between the experimentally obtained EIS profiles and the simulated data confirms the accuracy of the above simulations (Figure S5). Therefore, growing DTP-ANDI-COF on the CNT wires in situ to produce DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs significantly improves the electrical conductivity, while retaining the redox activity and porosity. We evaluated the BET surface area of the composite cathode, which was 210 m2 g−1 based on the total mass of the composite electrode and was 478 m2 g−1 based on the mass of DTP-ANDI-COF (Figure S6). The slight decreases in the BET surface area and pore size suggest that small segments of the binder PVDF molecules may enter into the pores. Nevertheless, the inherent porosity of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs is largely retained in the composite electrode.

Figure 4a presents the discharge-charge curves recorded for lithium-ion batteries with the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs cathodes after 100 cycles. The working potential was determined to be 2.4 V from the pseudo plateaus of the charge-discharge curves (Figure 4a). The plateaus retained their shapes after 100 cycles, demonstrating high energy-storage stability. The symmetric shape of the discharge-charge curves indicates that the oxidation and reduction processes are completely reversible. Furthermore, the Coulombic efficiency, defined as the ratio of the number of ions and electrons involved in the delithiation to the number of ions and electrons utilised in the lithiation, was retained at 100% throughout 100 cycles (Figure 4b, black line). This result unambiguously indicates that the electrons and ions involved in the oxidation and reduction reactions are utilised with 100% efficiency. The capacity of the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs was rather stable upon cycling and was retained at 67 mAh g−1, with a slightly increasing tendency during the initial five cycles as a result of the electrolyte penetration process (Figure 4b, red line). This capacity value corresponds to an efficiency of 82% for utilising the redox-active sites in the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs cathodes. DTP-ANDI-COF has a hexagonal polygon structure with three redox-active naphthalene diimide units in its unit cell (Figure 1b, c); theoretically, six electrons are involved in the charge and discharge processes in each unit cell. According to the above efficiency, each unit cell of DTP-ANDI-COF can accept or release as many as five electrons, on average, during the charge and discharge processes. The CNT cathodes without DTP-ANDI-COF exhibited a negligible capacity of only 2.5 mAh g−1 within the working voltage window from 1.5 to 3.5 V (Figure 4b, dotted black curve; Figure S7), indicating that the storage of energy and supply of power are driven by the redox-active DTP-ANDI-COF.

Performance of lithium batteries.

(a), Discharge-charge curves of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs upon 100 cycle at a rate of 2.4 C (red, 1st cycle; orange, 10th cycle; yellow, 20th cycle; green, 50th cycle; blue, 80th cycle; and purple, 100th cycle). (b), Capacities of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs (red line) and CNT (dotted black line) batteries and Coulombic efficiency of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs for 100 cycles (black line). (c), Discharge-charge curves of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs at different charge-discharge rates. (d), Capacity (red line) of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNT batteries upon continuous cycling at high current density and Coulombic efficiency (black line). (e), Capacity (red line) and Coulombic efficiency (black line) of DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs for 700 cycles at 2.4 C.

Discussion

After 100 cycles at a current density of 200 mA g−1 (corresponding to a rate of 2.4 C; n C represents full delivery of the theoretical capacity in 1/n h), the battery was subjected to further cycles at higher current densities to evaluate its high-rate performance during rapid charge and discharge processes (Figure 4c, d). We utilised a programme in which the rate increased from 2.4 C to 3.6 C, 6 C, 9 C and 12 C, which corresponds to the time periods for a complete discharge in 25, 17, 10, 7 and 5 min, respectively. Figure 4c presents the charge-discharge curves at each high rate. The profiles retained similar shapes without exhibiting any increased polarisation, indicating that the transport of ions and electrons into and out of the frameworks is sufficiently rapid to satisfy the rapid charge and discharge processes. Throughout these high-rate charge and discharge cycles, the Coulombic efficiency remained at 100% (Figure 4d, black line) and the working voltage was also unchanged (Figure 4c). These results demonstrate the excellent high-rate capabilities of the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs cathodes, which are superior to conventional organic cathodes (Table S2).

The capacity remained stable during cycling at each high rate; the decrease in capacity was quite small. For example, at 12 C, the capacity was 58 mAh g−1, which represents an 85% retention of the capacity at 2.4 C (Figure 4d, red line, Table S2). Although various different types of redox-organic cathodes have been developed (Table S2), rate performance remains a major issue to be resolved. The utilisation efficiency of the redox-active sites in the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs cathode is determined to be as high as 71% at 12 C, indicating that the batteries have high performance for high-rate charge and discharge. In contrast, in the absence of CNTs, the batteries of DTP-ANDI-COF cathodes at 12 C utilise only 5% of the redox-active units (Figure S4b). After the programmed high-rate cycles, the battery with the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs cathode was switched to a low-rate cycle at 2.4 C. The battery exhibited complete recovery of its capacity to 69 mAh g−1 (Figure 4d, red line) with an efficiency of 85% for utilising the redox-active sites (Table S2) and the charge and discharge curves were nearly identical to those of the first round of 100 cycles at 2.4 C.

Figure 4e shows the results from the long-term stability tests in which charge and discharge cycles were performed at a rate of 2.4 C. The batteries retained a nearly constant capacity even after 700 cycles and the Coulombic efficiency was maintained at 100% (Figure 4e, black line). The Coulombic efficiency of slightly over 100% is mainly caused by a minor parasitic reaction (electrolyte oxidation), as reported in leterature32,33. Such a long-term test has not been reported for other redox-active cathode materials (Table S2). The batteries achieved a capacity of 74 mAh g−1 (Figure 4e, red line) and the utilisation efficiency of the redox-active sites for energy storage was as high as 90%. The 100% capacity retention observed for the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs batteries is vastly superior to batteries employing other organic electrodes (Table S2), ranking the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs among the top class of redox-active organic cathodes.

DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs consist of crystalline, mesoporous, redox-active COFs on CNT wires. The covalent network of the redox-active units in the DTP-ANDI-COF ensures that DTP-ANDI-COF is insoluble in the electrolyte and significantly enhances the stability of the cathodes. Indeed, infrared spectra confirmed that the DTP-ANDI-COF linkages are well retained in DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs, even after 700 cycles (Figure S8). The redox-active units are located on the channel walls, which are easily accessible to ions via the open mesopores25,26,27. The in situ growth results in good contact between the COFs and CNTs (Figure 2h), thereby providing well-defined pathways for electron conduction (Figure 1e). The storage of energy clearly occurs on the redox-active walls in DTP-ANDI-COF rather than on the triphenylene nodes or on the other components in the electrodes. As a control, COF-5 (Figure S9a), which possesses knots and linkages identical to those of DTP-ANDI-COF but does not possess redox-active walls (Figure S9b, BET surface area = 1933 m2 g−1), was not electrochemically active (Figure 3b, dotted black curve) and exhibited a negligible capacity of only 1.6 mAh g−1 (Figure S9c). By using a typical redox-active imide group in the active components for energy storage, the DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs batteries could enhance the capacity by a factor of 18 fold and increase the efficiency by a factor of 22 fold in utilising redox-active units.

In conclusion, we introduce a new strategy and direction in the quest for energy storage using organic electrode materials. By developing crystalline, porous, redox-active frameworks on carbon wires for use as electrodes, we obtained the efficient utilisation of redox species, maximum Coulombic efficiency, robust high-rate capability and stable cycle performance for energy storage. This is made possible by the synergistic effects of DTP-ANDI-COF and CNTs in which the COF walls undergo multi-electron oxidation and reduction processes, the open mesopores facilitate the transport of ions into and out of the electrodes and the CNTs promote electron conduction. Together with the tunability of both the framework and pores of COFs via reticular chemistry along with the wide diversity of redox-active organic blocks, our results suggest that COFs on conducting carbons could provide a unique platform for energy storage. We envision that the highly ordered yet predesignable COF materials will facilitate the development of efficient, sustainable and environmentally benign energy-storage devices and technologies.

Methods

Synthesis of DTP-ANDI-COF and DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs

DTP-ANDI-COF was synthesised and characterised according to our previous report27. In a typical synthesis, a mixture of 2,3,6,7,10,11-hexahydoxytriphenylene (13 mg) with N, N′-di-(4-boronophenyl)-naphthalene- 1,4,5,8-tetracarboxylic acid diimide (30.2 mg, NDIDA) in a mixed solvent of DMF/mesitylene in a 10 ml Pyrex tube was degassed by being subjected to and sealed under vacuum. The tube was placed in an oven at 120°C for 7 days. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed with dehydrated DMAc and dehydrated dioxane and dried under vacuum to afford DTP-ANDI-COF with a 57% yield. DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs were synthesised using a similar procedure in the presence of CNTs (10 mg) and were obtained with a 62% yield. The content of DTP-ANDI-COF in DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs was 69 wt%, determined by subtracting the CNT mass from DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs.

Electrochemistry

Cathodes were prepared by spreading an N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP) slurry containing DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs active material, conductive carbon black (Super P Li, Timcal) and polyvinylidene fluoride binder (PVDF, Aldrich.) (7/2/2 by weight) on an aluminium plate using a coater. After drying in vacuum at 120°C to remove NMP, the cathode was cut into a round shape with a diameter of 12 mm and was pressed with 2 MPa for 1 min using hydraulic press (type: 769YP-15A). The total mass (M) of the cathode, including the aluminium plate, the active materials, conductive carbon black and PVDF, was scaled. Because the mass of aluminium plate was constant at 4.85 mg, the exact mass of active materials was determined using the equation of 7 × (M – 4.85)/(7 + 2 + 2). In our batteries, the mass of the active materials was approximately 1 mg. The cells were thus fabricated from the cathode, a polyethylene membrane separator, a lithium plate anode and 1 M LiPF6 electrolyte in a mixture of ethylene carbonate and dimethyl carbonate (1/1 by weight). All cells were tested at room temperature. The cells were galvanostatically cycled over a voltage range of 1.5–3.5 V using a Land Instruments model CT2001A. Cyclic voltammetry (CV; scan rate: 0.5 mV s−1; potential range: 1.5–3.5 V) and EIS (excitation signal of 5 mV and frequency range of 0.01–10,000 Hz) measurements were conducted using an IM6ex electrochemical workstation model from ZAHNER-electric GmbH & Co.

References

Armand, M. & Tarascon, J. M. Building better batteries. Nature 451, 652–657 (2008).

Nishide, H. & Oyaizu, K. Materials science - toward flexible batteries. Science 319, 737–738 (2008).

Armand, M. et al. Conjugated dicarboxylate anodes for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Mater. 8, 120–125 (2009).

Liang, Y. L., Tao, Z. L. & Chen, J. Organic electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 742–769 (2012).

Song, Z. P. & Zhou, H. S. Towards sustainable and versatile energy storage devices: an overview of organic electrode materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2280–2301 (2013).

Nishida, S., Yamamoto, Y., Takui, T. & Morita, Y. Organic rechargeable batteries with tailored voltage and cycle performance. ChemSuSchem 6, 794–797 (2013).

Liang, Y. L., Zhang, P. & Chen, J. Function-oriented design of conjugated carbonyl compound electrodes for high energy lithium batteries. Chem. Sci. 4, 1330–1337 (2013).

Morita, Y. et al. Organic tailored batteries materials using stable open-shell molecules with degenerate frontier orbitals. Nat. Mater. 10, 947–951 (2011).

Yang, Y. et al. Electrochemically synthesised polypyrrole/graphene composite film for lithium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 266–272 (2012).

Song, Z. P., Zhan, H. & Zhou, Y. H. Polyimides: promising energy-storage materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 8444–8448 (2010).

Wu, H. et al. Flexible and binder-free organic cathode for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 26, 3338–3343 (2014).

Xu, F. et al. Redox-active conjugated microporous polymers: a new organic platform for highly efficient energy storage. Chem. Commun. 50, 4788–4790 (2014).

Kang, B. & Ceder, G. Battery materials for ultrafast charging and discharging. Nature 458, 190–193 (2009).

Herele, P. S., Ellis, B., Coombs, N. & Nazar, L. F. Nano-network electronic conduction in iron and nickel olivine phosphates. Nat. Mater. 3, 147–152 (2004).

Feng, X., Ding, X. & Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6010–6022 (2012).

Côte, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 310, 1166–1170 (2005).

Doonan, C. J., Tranchemontagne, D. J., Glover, T. G., Hunt, J. R. & Yaghi, O. M. Exceptional ammonia uptake by a covalent organic framework. Nat. Chem. 2, 235–238 (2010).

Han, S. S., Furukawa, H., Yaghi, O. M. & Goddard, W. A. Covalent organic frameworks as exceptional hydrogen storage materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 11580–11581 (2008).

Ding, S. et al. Construction of covalent organic framework for catalysis: Pd/COF-LZU1 in Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19816–19822 (2011).

Xu, H. et al. Catalytic covalent organic frameworks via pore surface engineering. Chem. Commun. 50, 1292–1294 (2014).

DeBlase, C. R., Silberstein, K. E., Truong, T. T., Abruna, H. D. & Dichtel, W. R. β-Ketoenamine-linked covalent organic frameworks capable of pseudocapacitive energy storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16821–16824 (2013).

Chandra, S. et al. Phosphoric acid loaded azo (–N = N–) based covalent organic framework for proton conduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6570–6573 (2014).

Guo, J. et al. Conjugated organic framework with three-dimensionally ordered stable structure and delocalised π clouds. Nat. Commun. 4, 2736 10.1038/ncomms3736 (2013).

Wan, S., Guo, J., Kim, J., Ihee, H. & Jiang D. A photoconductive covalent organic framework: self-condensed arene cubes composed of eclipsed 2D polypyrene sheets for photocurrent generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 5439–5442 (2009).

Wan, S., Guo, J., Kim, J., Ihee, H. & Jiang, D. A belt-shaped, blue luminescent and semiconducting covalent organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 8826–8830 (2008).

Ding, X. et al. Synthesis of metallophthalocyanine covalent organic frameworks that exhibit high carrier mobility and photoconductivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 1289–1293 (2011).

Jin, S. et al. Large pore donor-acceptor covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 4, 4505–4511 (2013).

Jagiello, J. & Thommes, M. Comparison of DFT characterisation methods based on N2, Ar, CO2 and H2 adsorption applied to carbons with various pore size distributions. Carbon 42, 1227–1232 (2004).

Fang, Y. et al. Two-dimensional mesoporous carbon nanosheets and their derived graphene nanosheets: synthesis and efficient lithium ion storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1524–1530 (2013).

Fang, Y. J. et al. Mesoporous amorphous FePO4 nanospheres as high-performance cathode material for sodium-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 3539–3543 (2014).

Levi, M. D. et al. Solid-state electrochemical kinetics of Li-ion intercalation into Li1-xCoO2: simultaneous application of electroanalytical techniques SSCV, PITT and EIS. J. Electrochem. Soc. 146, 1279–1289 (1999).

Cho, J. H. & Picraux, S. T. Enhanced lithium ion battery cycling of silicon nanowire anodes by template growth to eliminate silicon under-layer islands. Nano Lett. 13, 5740–5747 (2013).

Kim, D. H., Je, S. H., Sampath, S., Choi, J. W. & Coskun, A. Effect of N-substitution in naphthalenediimides on the electrochemical performance of organic rechargeable batteries. RSC Advances 2, 7968–7970 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (24245030) from MEXT of Japan. R.F. thanks the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973, 2014CB932402) and the NSFC (51232005). D.W. thanks National Science Foundation for Excellent Young Scholars (No. 51422307), the NSFC (51372280 and 51173213) and the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars project (S2013050014408).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J. conceived the concept, directed and supported the project. F.X. prepared the COF@CNTs samples and performed the electrochemical experiments. H.Z. and X.Y. assisted in fabrications of the cells. S.J. performed the synthesis and provided the COF samples and X.C. participated in the monomer synthesis. D.W., R.F. and H.W. provided research advice. D.J. and F.X. wrote the manuscript. X.F. and S.J. contributed equally. H.W. is a visiting scholar from Shanghai Jiaotong University.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, F., Jin, S., Zhong, H. et al. Electrochemically active, crystalline, mesoporous covalent organic frameworks on carbon nanotubes for synergistic lithium-ion battery energy storage. Sci Rep 5, 8225 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08225

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08225

This article is cited by

-

Polyimide covalent organic frameworks as efficient solid-state Li+ electrolytes

Science China Chemistry (2024)

-

Industrial-scale synthesis and application of covalent organic frameworks in lithium battery technology

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2024)

-

Covalent organic frameworks

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2023)

-

Recent progress in COF-based electrode materials for rechargeable metal-ion batteries

Nano Research (2023)

-

Energy Storage in Covalent Organic Frameworks: From Design Principles to Device Integration

Chemical Research in Chinese Universities (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.