Abstract

We have developed a very sensitive, highly selective, non-destructive technique for screening inhomogeneous materials for the presence of superconductivity. This technique, based on phase sensitive detection of microwave absorption is capable of detecting 10−12 cc of a superconductor embedded in a non-superconducting, non-magnetic matrix. For the first time, we apply this technique to the search for superconductivity in extraterrestrial samples. We tested approximately 65 micrometeorites collected from the water well at the Amundsen-Scott South pole station and compared their spectra with those of eight reference materials. None of these micrometeorites contained superconducting compounds, but we saw the Verwey transition of magnetite in our microwave system. This demonstrates that we are able to detect electro-magnetic phase transitions in extraterrestrial materials at cryogenic temperatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 100 years ago Heike Kamerlingh Onnes accidentally discovered superconductivity in mercury1. This began the series of coincidences and surprises that have led to the discoveries of new superconductors. The major classes of superconductors (elements1, A15s2, cuprates3, diborides4 and pnictides5) were all discovered by an intuitive search or serendipity6,7,8. The search for superconductors is challenging for two principal reasons. First, a comprehensive theory that describes how to synthesize new superconductors is still missing, in spite of the enormous theoretical effort9,10,11,12 that has gone into understanding their behavior. Nevertheless, some interesting correlations between normal and superconducting state properties do exist13. Second, superconducting materials, in general, are very complex and exist only in a small region of a multielement, metallurgical phase-diagram. Therefore superconductors are hard to find as they may be embedded in non-superconducting materials or they just may be overlooked. The latter was demonstrated by the discovery of superconductivity in MgB2 in 20014, almost fifty years after the material was synthesized. To date, much effort has been invested in formulating a theory to explain superconductivity and in synthesizing superconductors, based on theoretical guiding principles. (For an innovative alternative approach involving phase spread alloys, see ref. 14). In contrast, we have advanced a method for the fast detection of superconductivity with very high sensitivity, which allows broad searches.

We have developed and improved a highly sensitive and selective technique for detecting minute amounts of superconducting materials embedded in an otherwise non-superconducting matrix15. Although conceived more than 20 years ago16,17,18, the original microwave absorption based technique was cumbersome and could not be used to look for superconductivity in many materials systems. In its present form, this non-destructive technique can measure a sample for superconductivity quickly (60 minutes in the range of 300–3.8 K) and very sensitively (10−12 cc of superconductor), allowing a large number of materials to be screened.

Since material synthesis is the bottleneck in the search for new superconductors we have extended our searches beyond artificially prepared materials to those found in nature, as originally proposed by H. Weinstock (private communications and ref. 19). Extraterrestrial materials are particular interesting. The analysis of extraterrestrial materials allows measurement of materials that cannot be synthesized in the laboratory. It is now well recognized that in many meteoritic classes there are presolar grains of oxides (Al2O3, MgAl2O4, CaAl12O19, TiO2, Mg(Cr,Al)2O4 as well as SiC, diamonds, graphite, Si3N4 and deuterium enriched organics20,21,22. These molecules were formed in some of the most intense physico-chemical environments in the Universe, including supernovae and stellar outflows. At the planetary level, the chondritic, achondritic and iron meteorites are derived from planetary processes associated with accretion/condensation, planetary differentiation and segregation23. These meteorites are some of the oldest, most pristine objects in the solar system and were created in a wide range of pressures and temperatures and have varied chemistry, ranging from highly reduced (e.g. iron meteorites) to highly oxidized meteorites containing organic material (carbonaceous chondrites). It is during such severe processes, when exotic chemical species may be created and may constitute the components of micrometeorites. Note that the conditions under which these form in many cases are not attainable under ordinary laboratory conditions and therefore they provide a unique source of exotic materials.

Our analysis method can detect minute amounts of superconductors embedded in a non-superconducting matrix and thus is the ideal method the search in these heterogeneous materials. We have started by investigating approximately 65 micrometeorites (with an average diameter of 200 μm and a total mass of approximately 0.6 mg) and eight reference samples (with a mass of approximately 1 mg) via Magnetic Field Modulated Microwave Spectroscopy (MFMMS).

Results

Detecting superconductivity using Magnetic Field Modulated Microwave Spectroscopy (MFMMS)

Since the discovery of superconductivity, different techniques have been developed to detect this property. The simplest methods are to measure the temperature dependence of the material resistivity and to measure the diamagnetic response. Although the resistivity measurement is the ultimate test, attaching electrodes to small, fragile samples is difficult and the results from inhomogeneous samples may not be representative. To circumvent these problems and to measure the perfect diamagnetism associated with superconductivity, the temperature dependent magnetization is measured using magnetometry or AC-susceptibility24,25,26. These techniques provide information regarding the diamagnetic properties of the superconductor. Both techniques require large, homogeneous sample volumes. Moreover, these techniques are relatively slow and compared to MFMMS, they require a larger amount of materials (10−9 cc).

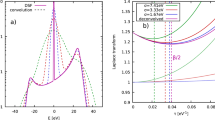

In our study, we use a Magnetic Field Modulated Microwave Spectroscopy (MFMMS) technique (see figure 1a and refer to ref. 15 for a detailed description). The materials under investigation are placed in a quartz tube. A continuous flow cryostat is used to scan the temperature from 300 K to 3.8 K. Simultaneously, a modulated magnetic field with an amplitude of 15 Oe and a frequency of 100 kHz is applied (see figure 1b). In a small temperature interval below the superconducting critical temperature, a small magnetic field can destroy the superconducting state and hence cause a significant change in the microwave absorption. The microwave absorption is monitored by a microwave cavity with a resonant frequency of 9.4 GHz. The modulated magnetic field causes the material to oscillate through the superconducting transition and this changes the cavity quality factor. This change is detected with a lock-in amplifier. A superconducting material typically causes a sharp characteristic peak (figure 1c) around the transition temperature.

To avoid confusion we should point out that the MFMMS technique differs from the FMR (Ferro Magnetic Resonance) based Microwave Resonance Thermomagnetic Analysis (MRTA), which was used to analyze the magnetite content of lunar materials27. In MFMMS, we minimize the FMR-response by using a special cavity-mode, where the magnetic microwave field is parallel to the external field and by applying only a small external magnetic DC-field15.

The sensitivity of the MFMMS is unmatched by other techniques for detecting superconductivity. We showed using patterned samples of Niobium (Nb) that 10−12 cc volumes produce a superconducting MFMMS signal with a signal-to-noise ratio of 3015. The same samples give no superconductivity signal by conventional techniques such as SQUID magnetometry. For pure superconducting materials, we estimate that SQUID measurements are three orders of magnitude below the MFMMS sensitivity (10−9 cc). For a mixture of superconducting and non-superconducting materials, the question of the highest sensitivity is far subtler and depends in particular on the material properties of the non-superconducting matrix. For instance, ferromagnetic materials could screen the diamagnetism of a superconductor and suppress the response in a SQUID magnetometer. Conducting materials screen microwaves and MFMMS would only detect superconductivity at or near the surface of the sample under investigation. However, we have tested the sensitivity of the MFMMS with a mixture of 1 mg (microwave absorbing) Fe3O4-powder and 0.1% (superconducting) bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide (BSCCO) powder and estimated a sensitivity of 10−8 cc. Even with this disadvantageous sample, the sensitivity of MFMMS is only one order magnitude worse than that of a SQUID magnetometer with an ideal sample.

Besides the sensitivity, MFMMS has other advantages: it is non-destructive, there are no specific sample geometry requirements and it is very fast. A typical scan over the entire temperature range, from 300 K to 3.8 K, takes only 1 hour.

Micrometeorites (MMS)

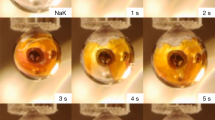

Micrometeorites (Fig. 2) are terrestrially collected extraterrestrial particles smaller than about 2 mm. They range from irregularly shaped unmelted particles to spheroidal, partially to wholly melted “cosmic spherules”. These materials contribute most of the mass accreted on the present day Earth28,29 and are samples of asteroids, the moon, Mars and cometary materials not represented in meteorite collections30. Estimates on the amount of this material entering the earth's upper atmosphere vary, with accepted values close to 30,000 ton/yr29. Although about 90% vaporize entering the atmosphere31 the MM accretion rate is, nevertheless, 100 times higher than that estimated for meteorites, 50 ton/yr32. Because of the large number of micrometeorites arriving on Earth, rare or unusual extraterrestrial materials may be more likely to be found in micrometeorite collections than in meteorite collections.

These samples are ideal to test our highly sensitive technique for detecting superconductivity, as individual MMs weigh 10−5 g. We selected different types of MMs to measure using MFMMS. About 65 MMs were segregated into four groups based on their textures. The first group consisted of spherules composed of glass, the second were spherules with barred-olivine textures, the third had porphyritic textures and the fourth were unmelted MMs. These classes represent differing degrees of atmospheric heating of incoming micrometeoroids.

MFMMS

Figure 3(a) shows the MFMMS data for approximately 50 melted micrometeorites placed in a quartz tube. A strong negative signal indicates the presence of an absorption mechanism around 300 K. This strong negative response slightly decreases down to a temperature of approximately 150 K. In an interval between 120 K and 50 K, the negative response increases and for temperatures below 50 K, stays at high negative values.

To investigate these materials further, we segregated the 50 micrometeorites into 3 sub-ensembles depending on their texture (the amount of material was approximately the same for all three sub-ensembles). The first sub-ensemble had barred-olivine texture, the second one had porphyritic texture and the last one consisted of glass micrometeorites33,34. The corresponding MFMMS-spectra are shown in figure 3c–e), respectively. The spectrum of the glass micrometeorites shows no response, while the spectra of the barred olivine and the porphyritic micrometeorite are very similar to the one of the whole ensemble. Figure 3(f) shows the MFMMS of the unmelted micrometeorites. The negative signal at 300 K stays constant until 200 K. Then it increases until 120 K. In the 120 K to 50 K interval it strongly decreases, followed by a small bump. To identify the materials that are responsible for the MFMMS-signal, we acquired the MFMMS for eight reference materials (see table 1). Two of those reference materials, magnetite and iron-rich olivine, had a detectable MFMMS as seen in figure 4. Magnetite I (Fig. 4a) is synthesized magnetite powder (Sigma Aldrich, particle size < 5 μm), while Magnetite II and Magnetite III (Fig. 4b–c) are test samples made of natural magnetite. Although there are differences between the three MFMMS of magnetite, the overall shape of the spectra are similar: from room temperature to approximately 100 K the signal is flat followed by sharp dip, after which the signal recovers somewhat, remaining below its original value.

Discussion

None of the four micrometeorite MFMMS scans in figure 3 has a characteristic peak that would indicate a superconducting transition such as shown in figure 1c. However, it was surprising that the micrometeorites showed a significant MFMMS response, since most materials (including ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic materials) show no response.

A comparison of the MFMMS depicted in figure 3a–d reveals, that the spectrum of the whole ensemble is approximately a superposition of the spectra of the constituents. The spectra of these micrometeorite ensembles are similar to the spectrum of synthetic magnetite depicted in figure 4a. In contrast, however, the MFMMS data of the unmelted micrometeorites resembles more the spectra of natural magnetite shown in figure 4b–c. Many micrometeorites contain magnetite, which forms as the micrometeorite is heated entering the Earth's atmosphere. Glass spherules cooled too quickly to form magnetite crystals, but small magnetite grains grow in the barred olivine and porphyritic MMs and the unmelted MM have thin magnetite rims.

In MFMMS, the magnetic field dependence of the microwave absorption for different temperatures is detected. Consequently, this technique is not only sensitive to superconductive transitions, but it can also probe the magneto-electric response of other materials35, relevantly magnetite36. The dip in the spectra of magnetite at 110–120 K (Fig. 4a–c) is caused by the Verwey transition37,38. Studies have shown that the magneto-electric properties of magnetite vary between different materials depending on variation in stoichiometry, stress, grain size, impurities etc.39. This explains the differences in the MFMMS characteristics (Fig. 4a–c).

It is hard to tell if the “bump” below 40 K in the MFMMS of barred olivine (Fig. 3b) is caused by magnetite (Fig. 4a) or by Fe-olivine (Fig. 4d).

Our first attempt to find superconductivity in extraterrestrial materials has established the methodology. Using a large number of micrometeorites we have obtained results from samples too small to analyze using any other techniques. We identified the presence magnetite in a large collection of micrometeorites collected in Antarctica, findings confirmed by other measurements. While to date we have found no evidence for superconductivity in the 65 micrometeorite investigated, these samples represent only a small portion of the extraterrestrial samples available and the search is going on.

Methods

MFMMS uses a customized X-band Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) apparatus. It includes a microwave circuit, a phase sensitive detector, an electromagnet, a cavity resonator and a flow cryostat, See Fig. 1. The cryostat allows sweeping the sample temperature between 3.8 K and 300 K. The sample is placed at the center of the cavity where the microwave electric field is minimum and the microwave magnetic field hmw is maximum. In addition to hmw, the sample is exposed to an external dc (hdc) and an ac (hac) magnetic field. The system measures the microwave absorption in-phase with the ac magnetic field as a function of the temperature or the dc magnetic field. Typical MFMMS measurements are acquired with an ac field (100 KHz) of hac = 15 Oe, a dc field of 15 Oe to 9000 Oe, a microwave power of 1 mW and at a 9.4 GHz frequency. The Microwave field and dc and ac fields are all parallel. The temperature is generally swept at 1–5 K/min. Details of the technique can be found elsewhere15.

Materials

We studied micrometeorites vacuumed from the bottom of the water well at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station33. These micrometeorites were deposited on snow between 700–1500AD and at the time of collection were 100 m below the snow surface, at the well water ice interface. The samples were hand-picked from sediment vacuumed from the bottom of the well.

We selected: Glass spherules, spherical particles composed of mafic glass; Barred olivine spherules that contain lathe-shaped olivine crystals and small magnetite crystals in interstitial glass; Porphyritic spherules that have equi-dimensional olivine or pyroxene crystals and magnetite crystals in interstitial glass; and unmelted MMs. The latter can be fine-grained with dark, compact matrices and chondritic compositions or coarse-grained and composed mainly of olivines and pyroxenes. Magnetite rims form on the surfaces of unmelted MMs during atmospheric entry heating40. For a detailed discussion of the chemical composition of MM please refer to ref. 33.

References

Onnes, H. K. The resistance of pure mercury at helium temperatures. Commun. Phys. Lab. Univ. Leiden 12, 120 (1911).

Izyumov, Y. A. & Kurmaev, Z. Z. Physical properties and electronic structure of superconducting compounds with the β-tungsten structure. Soviet Physics Uspekhi 17, 356 (1974).

Bednorz, J. G. & Müller, K. A. Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba−La−Cu−O system. Z. Physik, B 64, 189 (1986).

Nagamatsu, J., Nakagawa, N., Muranaka, T., Zenitani, Y. & Akimitsu, J. Superconductivity at 39 K in magnesium diboride. Nature 410, 63 (2001).

Takahashi, H. et al. Superconductivity at 43 K in an iron-based layered compound LaO1−xFxFeAs. Nature 453, 376. (2008).

Geballe, T. H. The never-ending search for high-temperature superconductivity. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 19, 261 (2006).

Hott, R., Kleiner, R., Wolf, T. & Zwicknagl, G. Review of superconducting materials. Handbook of Applied Superconductivity. Seidel P., ed. (ed.) (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, 2014).

Beasley, M. R. Search for New Very High Temperature Superconductors From an Applications Perspective. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercon. 23, 7000304 (2013).

Matthias, B. T. et al. Enhancement of superconductivity through lattice softening. Science 208, 401 (1980).

Abrikosov, A. A. Problem of super-high-Tc superconductivity. Physica C 468, 97 (2008).

Pickett, W. E. The next breakthrough in phonon-mediated superconductivity. Physica C 468, 126 (2008).

Tachiki, M. Overscreening mechanism for room temperature superconductivity. Physica C 468, 111 (2008).

Hirsch, J. E. Correlations between normal-state properties and superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 55, 9007 (1997).

de la Venta, J. et al. Methodology and search for superconductivity in the La–Si–C system. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 24, 075017 (2011).

Ramírez, J. G., Basaran, A. C., de la Venta, J., Pereiro, J. & Schuller, I. K. Magnetic Field Modulated Microwave Spectroscopy (MFMMS) across phase transitions and the search for new superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 093902 (2014).

Dulčić, A., Leontić, B., Perić, M. & Rakvin, B. Microwave Study of Josephson Junctions in Gd-Ba-Cu-O Compounds. Europhys. Lett. 4, 1403 (1987).

Kim, B. F., Bohandy, J., Moorjani, K. & Adrian, F. J. A novel microwave technique for detection of superconductivity. J. Applied Physics 63, 2029 (1988).

Stankowski, J. & Czyźak, B. Microwave absorption in high-Tc superconductors studied by the EPR method. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2, 465 (1991).

Feder, T. Minerals and meteorites: Searching for new superconductors. Physics Today 67, 20 (2014).

Thiemens, M. H. History and Application of Mass-Independent Isotope Effects. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 34, 217 (2006).

Nittler, L. R. Presolar stardust in meteorites: Recent advances and scientific frontiers. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 209, 259 (2003).

Clayton, D. D. & Nittler, L. R. Astrophysics with presolar stardust. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys 42, 39 (2004).

McSween, Jr H. Y. & Huss, G. R. Cosmochemistry. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2010).

Müller, K.-H., MacFarlane, J. C. & Driver, R. Josephson vortices and flux penetration in high temperature superconductors. Physica C 158, 69 (1989).

Win, W., Wenger, L. E., Chen, J. T., Logothetis, E. M. & Soltis, R. E. Nonlinear magnetic response of the complex AC susceptibility in the YBa2Cu3O7 superconductors. Physica C 17, 233 (1990).

Nikolo, M. Superconductivity: A guide to alternating current susceptibility measurements and alternating current susceptometer design. Am. J. Physics 63, 57 (1995).

Griscom, D. L., Marquardt, C. L. & Friebele, E. J. Microwave Resonance Thermomagnetic Analysis: A New Method for Characterizing Fine Grain Ferromagnetic Constituents in Lunar Materials. J. Geophys. Res. 80, 2935 (1975).

Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. Accretion of extraterrestrial matter during the last 80 million years and its effect on the marine Osmium isotope record. Geochem. Cosmochem. Acta 60, 3187 (1996).

Love, S. G. & Brownlee, D. E. A direct measurement of the terrestrial mass accretion rate of cosmic dust. Science 262, 550 (1993).

Bradley, J. P., Sandford, S. A. & Walker, R. M. Meteorites and the Early Solar System Kerridge J. F., & Matthews M. S., eds. (ed.) 861–895 (Univ. Arizona Press, Tuscon, USA, 1988).

Taylor, S., Lever, J. H. & Harvey, R. P. Accretion rate of cosmic spherules measured at the South Pole. Nature 392, 899 (1998).

Zolensky, M., Bland, P., Brown, P. & Halliday, I. Flux of extraterrestrial materials. Meteorites and the Early Solar System II Lauretta, D. S. & McSween, H. Y. (ed.) 869–888 (University of Arizona Press., Tuscon, Arizona, USA, 2006).

Taylor, S., Lever, J. H. & Harvey, R. P. Numbers, types and compositions of an unbiased collection of cosmic spherules. Meteorit. Planet. Sci 35, 651 (2000).

Genge, M. J. Engrand, C., Gounelle, M. & Taylor, S. The Classification of Micrometeorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 43, 497 (2008).

Alvarez, G., Font, R., Portelles, J., Zamorano, R. & Valenzuela, R. Microwave power absorption as a function of temperature and magnetic field in the ferroelectromagnet Pb(Fe1/2Nb1/2)O3 . J. Phys. Chem. Solids 68, 1436 (2007).

Gutiérrez, M. P., Alvarez, G., Montiel, H., Zamorano, R. & Valenzuela, R. Study of the Verwey transition in magnetite by low field and magnetically modulated non-resonant microwave absorption. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 316, e738 (2007).

Verwey, E. J. W. & Haayman, P. W. Electronic conductivity and transition point of magnetite (‘Fe3O4’). Physica 8, 979 (1941).

Walz, F. The Verwey transition - a topical review. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14, R285 (2002).

Muxworthy, A. R. & McClelland, E. Review of the low-temperature magnetic properties of magnetite from a rock magnetic perspective. Geophys. J. Int. 140, 101 (2000).

Toppani, A., Libourel, G., Engrand, C. & Maurette, M. Experimental simulation of atmospheric entry of micrometeorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36, 1377 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Andreas Morlock for pointing out the diversity of extraterrestrial materials and for the useful discussions at the beginning of our search for new superconductors. We thank Dr. H. Weinstock for his original idea on the search for superconductivity in unconventional materials. The micrometeorites were collected with support from the National Science Foundation. We acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Open Access Publishing Fund of Tuebingen University. Research supported by AFOSR grant FA9550-14-1-0202.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This is a highly collaborative research. I.K.S. generated the idea to develop the MFMMS for the systematic search for superconductivity. The equipment was setup and tested by I.K.S., A.C.B. and J.G.R.. I.K.S. started the collaboration with S.T. and M.T. who collected the samples. Most of the detailed laboratory work was done by S.G. who measured the samples and together with J.G.R., A.C.B. analyzed the data. J.W. performed sensitivity test measurements. S.G., J.G.R., A.C.B., M.T., S.T. and I.K.S. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Guénon, S., Ramírez, J., Basaran, A. et al. Search for Superconductivity in Micrometeorites. Sci Rep 4, 7333 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07333

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07333

This article is cited by

-

Search for New Superconductors: an Electro-Magnetic Phase Transition in an Iron Meteorite Inclusion at 117 K

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.