Abstract

The effect of n-type interlayer in hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes (WOLEDs) has been systematically investigated by using various n-type materials. A new finding, that the triplet energy rather than electron mobility or hole-blocking ability of interlayer plays a more positive role in the performance of hybrid WOLEDs, is demonstrated. Based on the new finding, a more efficient n-type interlayer bis[2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-pyridine] beryllium has been employed to realize a high-performance hybrid WOLED. The resulting device (without n-doping technology) exhibits low voltages (i.e., 2.8 V for 1 cd/m2, 3.9 V for 100 cd/m2) and low efficiency roll-off (i.e., 11.5 cd/A at 100 cd/m2 and 11.2 cd/A at 1000 cd/m2). At the display-relevant luminance of 100 cd/m2, a total power efficiency of 16.0 lm/W, a color rendering index of 73 and an extremely long lifetime of 12596265 h are obtained. Such superior results not only comprehensively indicate that the n-type materials are effective interlayers to develop high-performance hybrid WOLEDs but also demonstrate a significant step towards real commercialization in WOLEDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

White organic light-emitting diodes (WOLEDs) are now approaching mainstream display markets and also being aggressively explored for the next-generation lighting applications due to their extraordinary characteristics, such as high efficiency, fast switching and flexibility1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Generally, three types of WOLEDs are created according to the employed emitting materials, including all-phosphorescent WOLEDs, all-fluorescent WOLEDs and hybrid WOLEDs which are based on hybrid (fluorescent (F) and phosphorescent (P)) emitters schemes8,9,10. Among them, the utilization of P emitters is desirable since they can allow for a conversion of up to 100% of injected charges into emitted photons (both singlet and triplet excitons are harvested), resulting in a theoretical internal quantum efficiency of unity1. However, no proper blue P material can be obtained in terms of lifetime and color-stability until now, limiting the development of all-phosphor devices11. To loosen this bottleneck, researchers have devoted their attention to pursuing hybrid WOLEDs, which combine F blue emitters with P green-red/orange emitters to furnish white emission, due to their merits, high efficiency, stable color and long lifetime8.

For hybrid WOLEDs, the exchange energy losses (0.5–1.0 eV) originating from intersystem crossing from the host singlet into a blue phosphor triplet state are eliminated by dint of a blue fluorophore, improving the efficiency8. Meanwhile, with the smart device engineering, both singlet and triplet excitons are harvested along independent channels and thus nearly resonant energy transfer (ET) from the conductive host to dopants for both singlet and triplet energy (T1) can be realized8. In the last few years, the efficiency of hybrid WOLEDs has experienced a step-by-step increase and now can exhibit a maximum power efficiency (PE) of 58.4 lm/W12, which has already exceeded some of the best all-phosphorescent devices3. Besides, the color-stability limitations exist in all-phosphorescent WOLEDs has been greatly overcome by effective hybrid WOLEDs structures, such as using bipolar interlayer (IL) switch to manage carrier charges balance13,14, adopting multifunctional dopants to reduce charges mobility15 and preparing ultrathin emitting layers (EMLs) to produce white light16. However, while it is usually considered that hybrid WOLEDs have the potential of long lifetime since they comprise F blue emitters, no hybrid WOLED with long lifetime has been reported in the revealed literature so far, which also limits the further development of hybrid WOLEDs. To alleviate this difficulty, it is undoubtedly that an urgent endeavor is needed, although only rare effort has been taken to the lifetime of hybrid WOLEDs.

On the other hand, it is noted that a key feature of designing hybrid WOLEDs is the use of suitable ILs, locating between the F emitter and the P emitter8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. ILs can not only prevent Förster ET from the F blue emitters to the red-green/orange P emitters, but also eliminate the nonradiative Dexter ET between the two layers8. As a result, both singlet and triplet excitons are managed via ILs. In fact, a large number of effective ILs have been reported, such as 4,4-N,N-dicarbazolebiphenyl (CBP)8,12, TCTA: bis[2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-pyridine] beryllium (Bepp2)13,14, N,N′-di(naphthalene-1-yl)-N,N′-diphenyl-benzidine (NPB)15,16 and TCTA: 2,2′,2″-(1,3,5-benzinetriyl)-tris(1-phenyl-1-H-benzimidazole) (TPBi)17,18. However, it is noted that most of publications are focused on the bipolar or p-type ILs, only negligible attention was paid on the n-type ILs19,20. Moreover, no detailed investigation has been documented on the effect of n-type ILs in hybrid WOLEDs.

In this paper, we have systematically investigated the influence of n-type ILs by using four n-type materials, including tris(8-hydroxyquinoline) aluminum (Alq3), bis-(2-methyl-8-quinolinolate)-4-(phenylphenolato)aluminum (BAlq), bis(10-hydroxybenzo[h]quinolinato)beryllium complex (Bebq2) and TPBi. It is demonstrated a new finding that the T1 rather than electron mobility or hole-blocking ability of n-type ILs plays the crucial role in device performances. Based on the new finding, a more efficient n-type IL Bepp2 is employed to realize a high-performance hybrid WOLED. The resultant device (without n-doping technology) exhibits low voltages (i.e., 2.8 V for 1 cd/m2, 3.9 V for 100 cd/m2) and low efficiency roll-off (i.e., 11.5 cd/A at 100 cd/m2 and 11.2 cd/A at 1000 cd/m2). At the display-relevant luminance of 100 cd/m2, a total PE of 16.0 lm/W, a color rendering index (CRI) of 73 and an extremely long lifetime of 12596265 h are obtained. Such superior results not only comprehensively indicate that the n-type materials are decent ILs to develop high-performance hybrid WOLEDs but also demonstrate a significant step towards real commercialization in WOLEDs.

Results and discussion

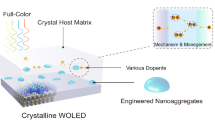

Figure 1 depicts the configuration of WOLEDs: ITO/MeO-TPD: F4-TCNQ (100 nm, 4%)/NPB (20 nm)/MADN: DSA-ph(20 nm, 7%)/ILs (0 or 3 nm)/Bebq2: Ir(MDQ)2(acac) (9 nm, 5%)/Bebq2 (25 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (200 nm), where ITO is indium tin oxide, F4-TCNQ is tetrafluoro-tetracyanoqino dimethane, MeO-TPD is N, N, N′,N′- tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl)-benzidine, DSA-ph is p-bis(p-N,N-di-phenyl-aminostyryl) benzene, MADN is 2-methyl-9,10-di(2-naphthyl)anthracene and Ir(MDQ)2(acac) is iridium(III)bis(2-methyldibenzo[f,h]quinoxaline)(acetylacetonate). Device W1, W2, W3, W4, W5 and W6 correspond to no, Alq3, BAlq, Bebq2, TPBi and Bepp2 IL, respectively.

To appropriately investigate the effects of n-type ILs in hybrid WOLEDs, several strategies are employed. First, to simplify structures, we utilized two complementary colors (blue/red) to give off white emission, although no two-color (blue/red) hybrid WOLEDs with n-type ILs has been reported. However, it should be pointed out that blue-orange color complement or three color system can also be used to study the effect of n-type ILs, which is expected to achieve similar results. Besides, it is noted that the first successful hybrid WOLEDs needs somewhat complicated structures which comprise the stacked F-IL-P-P-IL-F emitters8, we use the P-IL-F structures which only need double EMLs (one F EML and one P EML), leading to simplified fabrication processes and reduced cost. Next, Bebq2 is selected as an electron transport layer (ETL) since its electron mobility is as high as ~10−4 cm2/(V s)21, which can effectively enhance the electron injection and then make the carriers balanced. Bebq2 is also used as the host of red emitter, which can not only prevent reverse energy transfer from the dopants to the host as well as confining triplet excitons in the EML since the T1 of Bebq2 (2.25 eV)22 is higher than that of Ir(MDQ)2(acac) (2.0 eV)13, but also eliminate the structural heterogeneity exist between ETL and EML, boosting the efficiency and lifetime23. Finally, since the triplet ET (Dexter transfer) requires spatial overlap of the donor/accepter molecular orbitals and only occur significantly within a range of 1–2 nm17, 3 nm thick ILs are used to prevent this ET. Whereas, device A without IL is developed for comparison, which is expected to deeply understand the effect of n-type ILs. Based on these considerations, we studied the impact of n-type ILs in hybrid WOLEDs.

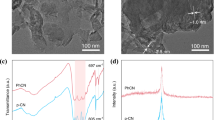

As illustrated in figure 2a, upon using different ILs, the electroluminescent (EL) spectra are dramatically affected. At a typical current density of 20 mA/cm2, the CIE coordinates of device W1, W2, W3, W4 and W5 are (0.194, 0.312), (0.194, 0.313), (0.197, 0.327), (0.194, 0.335) and (0.232, 0.323), respectively. An obvious red emission is generated in W5 while others only show negligible red colors. Hence, we cannot classify device W1, W2, W3 and W4 into WOLEDs because their colors are far away from the white equivalent-energy point of (0.333, 0.333).

Reasons for the above phenomena can be explained as follows. In general, the properties of n-type materials are affected by three key factors in phosphor-based devices, including electron mobility, hole blocking ability and T11,2. On one hand, since the electron mobilities of Alq3, BAlq, Bebq2 and TPBi are 10−5 cm2/(V s)21, 10−5 cm2/(V s)24, 10−4 cm2/(V s) and 10−4 cm2/(V s)25, respectively, electrons may be easier to pass through the Bebq2 and TPBi IL than Alq3 and BAlq IL, which leads to much more blue intensity in W4 and W5 than W2 and W3 and stronger red emissions are expected in W2 and W3. On the other hand, since the HOMOs of Alq3, BAlq, Bebq2 and TPBi are 5.8 eV21, 5.9 eV24, 5.995 eV26 and 6.2 eV25, respectively, holes may be difficult to pass through the TPBi IL than Alq3, BAlq and Bebq2 IL, which results in much more red intensity in W2, W3 and W4 than W5. Considering these two factors, device W2, W3 and W4 should exhibit more balanced white emissions than W5. However, contrary to the above reasons, white light can only be observed in W5 and others show negligible red emission. Therefore, it cannot be concluded that the electron mobility and hole blocking ability of the n-type IL are the main factors that affect the device performance. In fact, the T1, which usually has a great influence on the performance of phosphor-based devices1, is attributed to the main reason for the above phenomena. Since the triplet energies of Bebq2, Alq3, BAlq and TPBi are 2.25 eV, 2.03 eV27, 2.18 eV27 and 2.74 eV25, respectively, the low triplet energies of Alq3 and BAlq IL cannot prevent the diffusion of high-energy triplet excitons which generated in the red emissive regions, leading these excitons to the nonradiative triplet state of ILs and blue EMLs in W2 and W317. W1 without IL cannot eliminate the influence of Dexter ET between the F emitter and the P emitter because Dexter ET can occur within 1 ~ 2 nm, leading to a negligible red emission and hence we cannot obtain a balanced white color8. For W4 with the Bebq2 IL, the generated triplet excitons in the red region can still be easily transfer to the blue region due to the similar T1 of the Bebq2 IL and Bebq2 host, resulting in exciton quenching17. However, the mutual quenching can be effectively omitted by introducing the 3 nm TPBi IL owing to the high T1 (2.74 eV) and hence white light can be generated in W5. Besides, another interesting phenomenon is observed that the thicker TPBi IL is, the less red emission is, as shown in figure 2 inset. The phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that holes are difficult to pass through this IL bridge with increasing thickness (4.5 nm, 6 nm) since the TPBi is an n-type material. However, compared with the conventional work which used complicated methods to adjust the color of OLEDs, it is demonstrated that the color can be tuned by simply changing the n-type IL thickness, indicating a simplified but effective approach28.

Although W5 exhibits a white emission, its efficiency is not high, as shown in figure 3. The maximum forward-viewing CE and PE are 9.8 cd/A and 10.6 lm/W at 1 cd/m2, respectively. At 100 cd/m2, the CE and PE are 8.5 cd/A and 6.5 lm/W, respectively. To verify the new finding that the T1 rather than electron mobility or hole-blocking ability of n-type ILs plays the crucial role in device performances and to further improve the properties of WOLEDs with n-type ILs, we explored another n-type material Bepp2 as the IL because of its high T1 (2.6 eV)14, which can also be expected to avoid the mutual quenching between the F and P emitter. The efficiency of W6 with the Bepp2 IL is remarkably enhanced, as shown in figure 3. The maximum forward-viewing PE of W6 is 12.3 lm/W at 8 cd/m2. As illumination sources are typically characterized by their total emitted power8, our device exhibits a maximum total PE of 20.9 lm/W, which remains 16.0 lm/W and 11.9 lm/W at 100 cd/m2 and 1000 cd/m2, respectively, higher than the previous hybrid WOLEDs with n-type ILs19,20. The enhanced efficiency of W6 may be explained as follows. Although the electron mobility of Bepp2 is similar to TPBi8, the HOMO of Bepp2 (5.7 eV) is lower than that of TPBi (6.2 eV), which indicates that holes can be more easily transported into the red EML to form excitons and then harvested by Ir(MDQ)2(acac) which can manage both singlet and triplet excitons, enhancing the efficiency. More importantly, it is noted that the efficiency roll-off is rather low. For example, a maximum forward-viewing CE of 12.1 cd/A (a total CE of 20.6 cd/A) is achived at 8 cd/m2, which slightly rolls off to 11.5 cd/A at 100 cd/m2 and 11.2 cd/A at 1000 cd/m2.

Figure 4a presents the luminance-voltage-current density characteristics of W6, a turn-on voltage is 2.8 V (defined as the voltage at 1 cd/m2, 0.009 mA/cm2), which is the lowest value in the P-IL-F based WOLEDs using doped EMLs (without p-i-n or outcoupling structures) in the literature. At 100 cd/m2, the applied voltage is 3.9 V (0.919 mA/cm2) and a luminance of 58697 cd/m2 is obtained at 10.3 V (926.9 mA/cm2), higher than the previous WOLEDs with n-type ILs19,20. Since it is still a challenge for WOLEDs to achieve low driving voltages for practical use (e.g., <3 V for onset and <4 V at 100 cd/m2 for portable display)29, our device can alleviate this difficulty. Besides, the normalized EL spectrum is shown in figure 4a inset, a CIE coordinates of (0.277, 0.354) is obtained at 100 cd/m2, corresponding to a CRI of 73, which is the highest value in two-color (blue/red) WOLEDs with P-IL-F structures.

Finally, since the device lifetime is essential to practical use30,31,32, we have measured the lifetime of W6. As shown in figure 4b, a half lifetime of 75.9 h at an initial luminance of 10000 cd/m2 is obtained. To determine whether or not the lifetime is suitable for use in display luminance, an acceleration factor of 2.61 is obtained by measuring half-lifetimes at various initial luminances. Therefore, the lifetime is extrapolated to be 12596265 h at an initial luminance of 100 cd/m233, as shown in figure 4b inset. Even at an initial luminance of 1000 cd/m2, the lifetime is as long as 30920 h. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first hybrid WOLED with long lifetime in the revealed literature so far. Since the half lifetimes for TVs applications must be about 100000 h30, it is obviously seen that our device can satisfy this practical demand. On one hand, although all-fluorescent WOLEDs can exhibit long lifetime over 150000 h at 1000 cd/m2, the maximum efficiency is only 14.7 cd/A because the triplet excitons cannot be harvested34. On the other hand, although all-phosphorescent WOLEDs can exhibit fluorescent tube efficiency, the lifetime should be poor due to the P blue emitter35. However, since hybrid WOLEDs can manage both singlet and triplet excitons together with the fact that stable F blue emitters can be obtained, the trade-off between lifetime (12596265 h) and efficiency (20.6 cd/A and 20.9 lm/W) are realized, demonstrating a significant breakthrough in WOLEDs. Previous works have reported that hybrid WOLEDs can achieve high efficiency12, stable color13,14,15,16, herein, we have reported that hybrid WOLEDs can realize long lifetime, indicating an important step towards real commercialization.

In summary, we have investigated the effects of n-type ILs in hybrid WOLEDs and found that the T1 rather than electron mobility or hole-blocking ability plays the critical role in device performances. Intrigued by the achieved results, we have used Bepp2 as a more effective IL to obtain a high-performance hybrid WOLED. The resulting device can exhibit low voltage (2.8 V), high efficiency (16.0 lm/W), high CRI (73) and long lifetime (12596265 h) at a practical luminance of 100 cd/m2. Such presented facts will be beneficial to the design of both materials and device structures for WOLEDs in the emerging display and lighting applications.

Methods

All material layers were thermally deposited without breaking the vacuum at a base pressure of 2 × 10−7 Torr. In the deposition of the doping layers, deposition rates of both host and guest were controlled by their correspondingly independent quartz crystal oscillators. The devices were encapsulated immediately after preparation under a nitrogen atmosphere using epoxy glue and glass lids. The EL spectra, CIE color coordinates and CRI of packaged devices were obtained by a Konica Minolta CS2000 spectra system. The emission area of the devices is 3 × 3 mm2 as defined by the overlapping area of the anode and cathode. The luminance-current density-voltage characteristics were recorded simultaneously, using a computer-controlled source meter (Keithley 2400) and multimeter (Keithley 2000) with a calibrated silicon photodiode. The lifetime of the devices was tested through a 512 channel OLED testing system (New Vision Opto-Electronic Technology Co., Ltd) at a constant direct current density. All the measurements were carried out at room temperature under ambient conditions.

References

Wang, Q. & Ma, D. Management of charges and excitons for high-performance white organic light-emitting diodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 2387–2398 (2010).

Sasabe, H. & Kido, J. Development of high performance OLEDs for general lighting. J. Mater. Chem. C 1, 1699–1707 (2013).

Kwak, K., Cho, K. & Kim, S. Stable bending performance of flexible organic light-emitting diodes using IZO anodes. Sci. Rep. 3, 2787 (2013).

Wong, W.-Y. & Ho, C.-L. Functional metallophosphors for effective charge carrier injection/transport: new robust OLED materials with emerging applications. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 4457 (2009).

Zhou, G., Wong, W.-Y. & Suo, S. Recent progress and current challenges in phosphorescent white organic light-emitting diodes (WOLEDs). J. Photochem. Photobio. C: Photochem. Rev. 11, 133 (2010).

Ying, L., Ho, C.-L., Wu, H., Cao, Y. & Wong, W.-Y. White polymer light-emitting devices for solid-state lighting: materials, devices and recent progress. Adv. Mater. 26, 2459 (2014).

Yang, X., Zhou, G. & Wong, W.-Y. Recent design tactics for high performance white polymer light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 1760 (2014).

Sun, Y. et al. Management of singlet and triplet excitons for efficient white organic light-emitting devices. Nature 440, 908–912 (2006).

Ho, C.-L. et al. A multifunctional iridium-carbazolyl orange phosphor for high-performance two-element WOLED exploiting exciton-managed fluorescence/phosphorescence. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 928 (2008).

Wang, Q. et al. Reduced efficiency roll-off in highly efficient and color-stable hybrid WOLEDs: The influence of triplet transfer and charge-transport behavior on enhancing device performance. Org. Electron. 11, 238 (2014).

Ishisone, T., Seo, S., Nonaka, Y., Kawata, T. & Ohsawa, N. Highly efficient single-unit white OLED device with emission from both singlet and triplet excitons. SID DIGEST 52, 762–765 (2014).

Liu, B. et al. Investigation and optimization of each organic layer: A simple but effective approach towards achieving high-efficiency hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes. Org. Electron. 15, 926–936 (2014).

Zhao, F., Sun, N., Zhang, H., Chen, J. & Ma, D. Hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes with a double light-emitting layer structure for high color-rendering index. J. Appl. Lett. 112, 084504 (2012).

Zhao, F. et al. A hybrid white organic light-emitting diode with stable color and reduced efficiency roll-off by using a bipolar charge carrier switch. Org. Electron. 13, 1049–1055 (2012).

Wang, Q. et al. Reduced efficiency roll-off in highly efficient and color-stable hybrid WOLEDs: The influence of triplet transfer and charge-transport behavior on enhancing device performance. Org. Electron. 11, 238–246 (2010).

Liu, B. et al. High-performance hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes comprising ultrathin blue and orange emissive layers. Appl. Phys. Express. 6, 122201 (2013).

Schwartz, G., Fehse, K., Pfeiffer, M., Walzer, K. & Leo, K. Highly efficient white organic light emitting diodes comprising an interlayer to separate fluorescent and phosphorescent regions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 083509 (2006).

Schwartz, G., Reineke, S., Walzer, K. & Leo, K. Reduced efficiency roll-off in high-efficiency hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 053311 (2008).

Xia, Z. Y., Su, J. H., Chang, C. S. & Chen, C. H. Hybrid white organic light-emitting devices based on phosphorescent iridium–benzotriazole orange–red and fluorescent blue emitters. J. Lumin. 135, 323–326 (2013).

Ho, C. L., Lin, M. F., Wong, W. Y., Wong, W. K. & Chen, C. H. High-efficiency and color-stable white organic light-emitting devices based on sky blue electrofluorescence and orange electrophosphorescence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 083301 (2008).

Liao, S. H. et al. Hydroxynaphthyridine-derived group III metal chelates: wide band gap and deep blue analogues of green alq3 (tris(8-hydroxyquinolate)aluminum) and their versatile applications for organic light-emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 763–777 (2009).

Tsuboi, T. Recent advances in white organic light emitting diodes with a single emissive dopant. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 356, 1919–1927 (2010).

Li, Y. et al. A single-heterojunction electrophosphorescence device with high efficiency, long lifetime and suppressive roll-off. Synth. Met. 164, 12–16 (2013).

Seo, J. H. et al. High-efficiency deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes using dual-emitting layer. Org. Electron. 11, 1605–1612 (2010).

Gao, C. H. et al. Enhancement of electroluminescence efficiency and stability in phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes with double exciton-blocking layers. Org. Electron. 14, 1177–1182 (2013).

Pyo, S. Y. et al. White-light-emitting organic electroluminescent devices using new chelate metal complexes. Thin Solid Films 363, 232–235 (2000).

Tanaka, I., Tabata, Y. & Tokito, S. Förster. Dexter energy-transfer processes in fluorescent BAlq thin films doped with phosphorescent Ir(ppy)3 molecules. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 073501 (2006).

Teng, M. Y. et al. Color changeable OLEDs controlled by doping ratio and driving voltage with an anthracene derivative doped layer. RSC Adv. 2, 10175–10178 (2012).

Zhang, Z. et al. Low driving voltage white organic light-emitting diodes with high efficiency and low efficiency roll-off. Org. Electron. 14, 2172–2176 (2013).

Ni, S. Y. et al. Decay mechanisms of a blue organic light emitting diode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 878 (2004).

So, F. & Kondakov, D. Degradation mechanisms in small-molecule and polymer organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 22, 3762–3777 (2010).

Nakanotani, H., Masui, K., Nishide, J., Shibata, T. & Adachi, C. Promising operational stability of high-efficiency organic light-emitting diodes based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Sci. Rep. 3, 2127 (2013).

Chu, T. Y., Chen, J. F., Chen, S. Y. & Chen, C. H. Comparative study of single and multiemissive layers in inverted white organic light-emitting devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 113502 (2006).

Duan, L. et al. Controlling the recombination zone of white organic light-emitting diodes with extremely long lifetimes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 3540–3545 (2011).

Reineke, S. et al. White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature 459, 234–238 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 61204087, 51173049, 61306099 and 61401156), the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. S2012040007003), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2013M531841), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2014ZM0034) and Guangdong Innovative Research Team Program (No. 201101C0105067115).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. conceived the idea and wrote the paper, L.W., M.X., H.T., J.Z. and L.L. performed OLED device studies, data analysis and provided detailed insights into the device engineering, H.N. made a detailed discussion and gave some suggestions for revising the manuscript, D.G. performed devices fabrication, J.P. and Y.C. initiated and supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Wang, L., Xu, M. et al. Efficient hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes with extremely long lifetime: the effect of n-type interlayer. Sci Rep 4, 7198 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07198

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07198

This article is cited by

-

Efficient white phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes using ultrathin emissive layers (<1 nm)

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Regulating Charge and Exciton Distribution in High-Performance Hybrid White Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with n-Type Interlayer Switch

Nano-Micro Letters (2017)

-

Extremely high-efficiency and ultrasimplified hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes exploiting double multifunctional blue emitting layers

Light: Science & Applications (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.