Abstract

Hydroxyapatite (HAP), similar to inorganic phase in bones, shows good biocompatibility and bioactivity as bone defect repairing material. Recently, nanoscaled HAP shows the special properties differing from bulk HAP in physics, chemistry and biology. This paper demonstrates that HAP nanoparticle (nHAP) possesses the ability for inhibiting cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, after treatment with nHAP for 3 days, proliferation of human cancer cells are inhibited by more than 65% and by less than 30% for human normal cells. In vivo, injection of nHAP in transplanted tumor results in significant reduction (about 50%) of tumor size. The anticancer effect of nHAP is mainly attributed to high amount by endocytosis in cancer cells and inhibition on protein synthesis in cells. The abundant nHAP internalized in cancer cells around endoplasmic reticulum may inhibit the protein synthesis by decreasing the binding of mRNA to ribosome due to its high adsorption capacity for ribosome and arrest cell cycle in G0/G1 phase. nHAP shows no ROS-involved cytotoxicity and low cytotoxicity to normal cells. These results strongly suggest that nHAP can inhibit cancer cell proliferation and have a potential application in cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydroxyapatite (HAP), a member of the calcium phosphate compounds, is present as the mineral or inorganic phase in hard tissues (bones and teeth) of vertebrates. HAP is a biocompatible material and has high binding activity to DNA and proteins. HAP-based biomaterials are currently used in bone and tooth repair1,2. In natural bone, carbonate HAP nanocrystals (about 50 nm × 25 nm × 2–5 nm) are regularly scattered in the compartments of organic matrix to form composite structure with excellent mechanical properties3. Moreover, nanoscaled HAP has displayed unique functions differing substantially from those of bulk or microscale HAP, for example, increased fracture toughness and hardness of HAP ceramic4,5, improved osseointegrative property on nanostructured HAP ceramic5,6, enhanced adsorption capacity to drug/gene/protein of apatite nano carrier and high solubility in acidic pH environment of cellular endolysosomes7,8.

Since the 1990s, the inhibitory effect of HAP ultrafine (nano) particle (nHAP) on the proliferation of cancer cells was investigated and reported9,10, generating great interest in material science and applied medicine communities11,12,13,14. In our earlier study, we observed that nHAP inhibited the proliferation of some cancer cell lines and showed much greater inhibitory effect on cancer cell line than on normal cell line. Until now, to our knowledge, the mechanism of inhibitory effect of nHAP on the proliferation of cancer cells and difference in inhibition between cancer cell and normal cell has not been well revealed. So, we further investigate the inhibitory effect and mechanism of nHAP on cancer cells in vitro and in vivo.

In the present work, we further investigate the anticancer effect and mechanism of nHAP as one kind of inorganic medicine in vitro and in vivo. The different inhibitory effects of nHAP on the cell proliferation are studied within normal and cancer cells as well as between normal cells and cancer cells. The treatment time, particle size and dosage effects of nHAP on inhibition of cell proliferation are investigated between cancer cells and normal cells. The in vitro and in vivo anticancer effect mechanism of nHAP is discussed on the basis of studies of cell cycle, protein synthesis, SDH and SOD, adsorption of BSA, DNA and RNA.

Results and Discussion

We compare the inhibitory effects of nHAP on the cell proliferation of several normal cells with several cancer cells. Three human cancer cell lines - MGC-803, Os-732, Bel-7402 and three human normal cell lines - hepatocytes (L-02), lung fibroblast (MRC-5), keratinocyte (HaCaT) are investigated using MTT assay. Results show that nHAP can inhibit the proliferation of both human cancer cells and normal cells (Table 1). However, the inhibitions of cancer cell proliferation are much greater than those of normal cell proliferation at low and high nHAP concentration respectively. Differences in inhibition degree of cell proliferation between cancer cells and normal cells are over 30% and up to 70% depending on cell lines. In addition, there are differences in inhibition degree within different cancer cell lines and within normal cell lines. For example, the inhibitions for MGC-803, Os-732 and Bel-7402 are 54.3–65.0%, 60.6–75.8% and 76.3–88.0% respectively. These results suggest that the inhibitory effect of nHAP may be cell type related or cell-type specific.

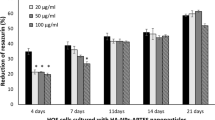

The inhibitory effects of nHAP on cell proliferation are also dependent on treatment time. Two comparable cell lines, Bel-7402 (cancer) and L-02 (normal) are determined at different time points. These cells are both from the human liver and their sensitivities to nHAP have been shown to be typical among cancer cells and normal cells. nHAP results in different inhibitions of cell proliferation of Bel-7402 and L-02 cells during 3 days treatment. The inhibition of cell proliferation of Bel-7402 is quickly increased from about 25% to 76% along with a little increase of proliferation inhibition from about 15% to 24% for L-02 (Figure 1). The inhibitory effect of a traditional cancer drug, sodium cantharidinate (SCA), is also tested. It is observed that there is no significant difference in the inhibitory effects of SCA on L-02 cells and Bel-7402 cells, which are all quickly increased from about 40% to over 80%. At the third day, SCA only shows a little higher inhibitory effect on Bel-7402 cells (about 10%) than that of nHAP. However, SCA shows a strong toxic effect on L02 cells, which is about 2 times larger than that of nHAP. These results indicate that nHAP treatment is safer than SCA used in cancer chemotherapy.

It is also observed that the inhibitory effect of nHAP on cancer cells is dependent on the particle size and the dosage (Figure 2). Greater degree of inhibition is observed with smaller HAP particles. At the concentration of 0.56 gL−1, along with the decrease of particle size from about 290 nm to about 170 nm and 60 nm, the inhibition of HAP particles on Bel-7402 is significantly increased from about 20% to about 40% and 75% respectively. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of nHAP on Bel-7402 shows strong dependent on dosage of nHAP. The inhibition is almost linearly increased from about 15% to about 40% and 75% with the rising of concentration (0.14 gL−1, 0.35 gL−1, 0.56 gL−1).

The in vivo anticancer effect of nHAP is tested by directly injecting into nude mice transplanted tumors (Figure 3). Results show the vacuolization in the cytoplasm and chromatin condensation induced by nHAP but not in the untreated control. More than 50% decrease in the tumor size is observed on the 7th day after nHAP treatment. In addition, the survival time of the infected nude mice is increased from 72.3 ± 7.3 days to 104.9 ± 6.2 days.

Generally, nanoparticles could enter into cancer cells and distribute in different organelles depending on the characteristics of the nanomaterials15. In this study, there is a significant difference in the number of internalized nHAP between cancer cells and normal cells (Figure 4). In order to compare the number of internalized nHAP by cancer cells and normal cells, nHAP was doped with Eu3+ ions to have fluorescence signal for the observation under confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). A greater number of nHAP in treated cancer cells is observed than that in treated normal cells, which may explain the observed difference in the degree of inhibition by nHAP between cancer cells and normal cells. This phenomenon should be attributed to the characteristics of nHAP as well as cancer cells. As we know, HAP possesses two different binding sites on the crystal surface16, which are C (Ca2+) site arranged on ac or bc crystal faces for binding the acidic groups of the biomolecules and P (PO43−) site arranged hexagonally on the ab crystal face for attaching to the basic groups of the biomolecules. Abundant negatively charged groups on the surface of cancer cells generate more negative charge of cancer cells than normal cells, which are mainly deriving from the sialic acid residues protruding from the apical surface of the plasma membrane. Our previous study demonstrated that nHAP showed high adsorption capacity for sialic acid than HAP microparticles and could attach to the membrane of RBCs (non-phagocytic cells) with abundant sialic acid residues17. Consequently, nHAP can be expected to have higher adhering capacity to cancer cells than normal cells on the basis of the electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged sites on the cell membrane and the positive binding sites on the HAP surface18. In addition, relative experiments show that nHAP enters into the cells through endocytosis19. Since the nHAP prepared in this study was not loaded with cancer cell-specific drug or cytoplasma membrane-binding molecule, the difference in the numbers of nHAP entering into cells between L-02 normal cells and Bel-7402 cancer cells can be attributed to the harvest pathway of the cells. Since the endocytosis activity of cancer cells is greater than that of normal cells20,21,22,23, the observed much more nHAP in Bel-7402 cells than that in L-02 cells can be expected.

The distribution of nanoparticles in the cell structure is closely related to their biological activities. In this study, nHAP is internalized into cancer cells and mostly distributed around endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Figure 4 and 5a), the organelle responsible for protein and lipid synthesis. Also, it is observed that after nHAP treatment, the percentage of cancer cells in different phases of cell cycle changes considerably. There is a 24.2% increase of G0/G1 cells, while 38.2% and 12.9% decrease of S and G2/M cells, respectively (Figure 6). During the cell proliferation, the cell cycle is divided into major events occurring during different phases: G0, G1, S, G2, M. Cell divides in the M phase, while the major substances preparation such as protein synthesis and DNA duplication mainly happens in G1 phase and S phase, respectively. The progress of cell cycle depending on different environmental conditions can be significantly changed by the extrogenous substance treatment24,25. Accordingly, these results indicate that the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation may be due to the decrease of protein synthesis or lack of key proteins for cell cycle progression after nHAP treatment.

In order to prove this hypothesis, the synthesis of transferrin receptor (TR) in vivo and enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) by cell-free protein synthesis system were detected after nHAP treatment. A decrease in the TR amount (differing in amounts) occurs on the membranes of both the cancer cells and the normal cells. The reduction is 55.6% in the cancer cells and 23.2% in the normal cells (Figure 7a). Moreover, after nHAP treatment, EGFP produced by cell free protein synthesis system in the cancer cell is decreased by 71.0% similar to that of the normal cells (Figure 7b). These results suggest that nHAP has similar inhibition effect on the translation process of cancer cells to that of normal cells in vitro. However, since there are different amounts of nHAP internalized into the cells, the different levels of the decrease of TR amounts between the cancer cells and normal cells can be expected. This generates the difference in the degree of inhibition between normal cells and cancer cells.

The effect of biomaterials on the local cells is determined by the amount and activity of the proteins in the interface26. Ribosome is mainly composed of proteins and RNA and can be purified by HAP with high adsorption activity27. Our results show that HAP particles display different adsorption capacity for BSA, DNA and RNA (Table S1). Moreover, HAP particles with varied size show different adsorption capacity. Along with the decrease of size from 290 nm to 170 nm and 60 nm, the adsorbed DNA amount on HAP particles (per g) is much increased from 0.43 g to 1.36 g and 1.12 g; the adsorbed BSA amount is raised from 33.33 mg to 42.40 mg and 55.47 mg; however, for RNA the amount on nHAP (60 nm) is decreased compared to those of larger HAP particles.

Two main possibilities may lead to the inhibitory effect of HAP on the protein synthesis. The interaction of the ribosome with HAP inhibits the further binding of ribosome with mRNA, or mRNA bound by HAP cannot reach its proper binding site in the ribosome. Generally, HAP has poor binding activity to mRNA28. It is also observed in this study that there is almost no mRNA binding with HAP (Table S1). However, the binding of ribosome with mRNA is decreased significantly after nHAP treatment (Figure 7c). Because the ribosome can be purified by HAP, these results indicate that nHAP may inhibit the protein synthesis by interacting with the ribosome and decreasing the binding of mRNA to its proper binding site in the ribosome, which further induces the inhibition of cell proliferation. Based on the higher fraction of C and P sites of nHAP due to its higher specific surface ratio than that of larger HAP particles, the greater binding activity of nHAP with ribosome can be achieved. In addition, cancer cells show much higher internalization of nHAP than that of HAP microparticles (Figure 5). Consequently, the higher inhibition of nHAP on the proliferation of cancer cells can be expected.

Recently, it was reported that some active nanomaterials, such as carbon nanotubes and metal oxides nanomaterials can release reactive oxygen species (ROS) from their surfaces and treatment with these nanomaterials induced an increase of cellular ROS and promoted cell death29. While such treatment can be used to kill cancer cells, it was also shown to be equally toxic to normal cells26,30. In this study, the activities of succinate dehydrogenase and superoxidase dismutase, the key enzymes responsible for ROS generation and scavenge, respectively, are significantly decreased and remained unchanged after nHAP treatment (Table S2). Moreover, the apoptotic/live cell ratios in the control cells and the treated cells are almost same. These results suggest that the mechanism for the inhibitory effect of nHAP treatment is not explained by ROS release. Instead, it may be concluded that the inhibitory effect of nHAP treatment on cell proliferation is due to the blocking of cell cycle by decreasing the protein synthesis.

Malignant tumor is one of the most serious life-threatening human diseases. Presently, chemical and radiation therapies remain the basic treatments for cancer. However, these therapies have serious side effects, including toxicity and complications. There is therefore an urgent need for a safer cancer treatment, which will inhibit the growth of cancer cells but not of the normal cells. The development of nanotechnology provides novel techniques in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Our results in vitro and in vivo demonstrate that nHAP has much greater inhibitory effect on cancer cell proliferation than that of normal cells and extends the longevity of animals with tumors. nHAP treatment can decrease protein synthesis directly, block cell cycle and thus inhibit cell proliferation. The difference in the ingestion activity of nHAP between normal cells and cancer cells leads to a greater inhibition of cancer cell proliferation than that of normal cells. Considering the biocompatibility and biodegradation, as anticancer agent or drug carrier, nHAP or nHAP combined with chemotherapeutic drugs is hopeful to be safe and effective alternative for cancer treatment.

Methods

Preparation of nHAP

nHAP was prepared referring to Ref. 31. According to the molar ratio of Ca/P of 1.67, Ca(H2PO4)2·H2O aqueous solution was rapidly mixed with saturated Ca(OH)2 aqueous solution with rapid stirring. Then, the stabilizer of sodium heparin was added into the above suspension with a final concentration of 0.4 g L−1. Next, the turbid dispersion was ultrasonically irradiated for 8 min by a high-intensity ultrasonic probe to be transparent suspension. Finally, the transparent suspension was treated by mosit-heat sterilization at 121°C for 1 h.

The details for preparing large HAP particles32,33 and characterization were shown in Supplementary Information.

X-Ray Diffraction

Powder X-ray Diffraction (XRD, D/Max-IIIA, RIGAKU, Japan) was utilized to identify the crystalline phase. The crystallite size was calculated by Scherrer's formula as follows: Xhkl = kλ/β1/2cosθ, where Xhkl is the crystallite size (nm); λ the wavelength of monochromatic X-ray beam (nm); β1/2 the full width at half maximum of diffraction peak; θ the diffraction angle (°); and k is a constant varying with crystal habit and chosen to be 0.9. The diffraction peaks of (002) and (310) Miller's plane families were used to calculate the crystallite sizes of HAP, showing the crystal growth along the c-axis and along a direction perpendicular to c-axis of HAP crystalline structure. The crystallinity degree (Xc) of HAP powders was evaluated by the equation: Xc ≈ 1–V112/300/I300, where I300 is the intensity of (300) diffraction peak and V112/300 is the intensity of the hollow between (112) and (300) diffraction peaks.

FT-IR

HAP powders were prepared as wafer with 10 mm in diameter by infrared-transparent KBr pressed disc method. The resolution of infrared is 0.17 cm−1 while the wavelength lies between 2.5 μm and 25 μm. The obtained FT-IR spectrum was then compared with the standard spectrum for anion group identifying.

The human cell lines and determination of cell growth curve

Os-732 osteosarcoma cell line and the MGC-803 gastric carcinoma cell line were provided by Huazhong University of Science & Technology and Peking University, respectively. The other cell lines of Bel-7402 (hepatocellular carcinoma cell line), L-02 (hepatocyte), MRC-5 (lung fibroblast) and HaCaT (keratinocyte) were provided by China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC) of Wuhan University. These cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were seeded in a 96-well plate or a 25 cm2 culture bottle at a density of 1 × 105 cell ml−1. After 24 h, when the cells were adjacent to the plate bottom, the culture media were replaced with treatment media. All treatment media contained 90% culture medium, 10% FBS and different amount of nHAP at the final concentrations of 0.14 g L−1, 0.35 g L−1 and 0.56 g L−1, respectively. The absorbance at 570 nm was determined by microplate reader (Thermo Labsystems) according to the MTT method and the degree of inhibition expressed as percent (%) was calculated as [(Acontrol-Atreated)/Acontrol] × 100.

Observation with TEM

The cells after nHAP treatment were collected and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1% osmic acid. Both samples were dehydrated in graded ethanol, embedded in epoxy resin and sectioned using an ultramicrotome (LKB-V). The sections were double stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate and thereafter observed with transmission electron microscopy (TEM, H-600, Hitachi).

Observation with CLSM

Bel-7402 and L-02 cells were cultured in glass bottom cell culture dishes (35 mm). Both cells were treated with Eu-nHAP for 2 days. After that, the cells were washed with phosphate buffer salt solution (PBS) and the nucleus and ER were stained with DAPI and DiOC6(3)34, respectively. The solution was replaced by culture medium before CLSM observation (AOBS SP2, Leica). The excitation wavelengths were set at 405 nm, 488 nm and 543 nm, respectively for DAPI, DiOC6(3) and Eu-nHAP.

Analysis of cell cycle by flow cytometry

The cells treated with nHAP were collected and resuspended in PBS. Then they were stained with propidium iodide (PI, 50 mg L−1) at 4°C for 30 min. The cell cycle distributions were measured by flow cytometry (BD FACSort).

Transfection of pEGFP-C1 into Bel-7402 and L-02

Polyethylenimine- (PEI) mediated plasmid transfection were performed according to Boussif et al.35. The plasmid pEGFP-C1 was purified from DH5α and mixed with PEI in salt solution. The cells were observed after 24 h by CLSM at Ex488/Em 510. The positive preparation was cultured for 2 days, total RNA was extracted and purified.

Protein expression assay

The measurement of TR expression in vivo by FITC labelled transferrin was performed according to Hedley et al.36. And the expression of EGFP was performed in vitro with the cell-free protein synthesis system (RTS 100 Wheat Germ CECF Kit, Roche). Briefly, total RNA pufiried from Bel-7402 or L-02 cells was mixed with the reaction solutions and different amount of nHAP and incubated at 24 °C for 24 h. The fluorescence emission of the reaction solutions was then detected for EGFP at Ex488/Em510.

Measurement of the binding of ribosome with mRNA

mRNA was extracted and purified from rat liver. The extracted mRNA was oxidized and cross-linked with the fluorophore according to Proudnikov & Mirzabekov37 except with Alexa Fluor 488 hydrazide (AF488) replacing of tetramethylrhodamine hydrazide. The ribosomes containing extracts of Bel-7402 and L-02 cells were isolated from the cell lysates by collecting of the supernatants after centrifuge at 50,000 × g, 4 °C for 30 min. The AF488-mRNA was mixed with the ribosomes containing extracts and different amounts of nHAP in resuspension buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM KCl, pH7.4) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then the mixtures were centrifuged at 150,000 × g, 4 °C for 2 h. The pellets were resuspended and the fluorescence signals were detected at Ex490/Em520.

Determination of succinate dehydrogenase and superoxidase dismutase activity

The livers from health Wister rats (animal weight 160–200 g) were homogenized at 600 rpm in ice bath. The crude homogenate was filtrated and centrifuged to sediment the mitochondrial fraction according to Kennes38. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity was measured by 2,6-DPTP reduction with SDH Detection Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Inst., China). And total superoxidase dismutase (SOD) activity of mitochondria was determined by hydroxylamine assay with SOD Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Inst., China).

Adsorption of DNA, RNA and protein on HAP

Plasmid DNA of pUC18 was purified from DH5α by TIANprep Mini plasmid purification Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co. Ltd., China). Total RNA was isolated from rat liver according to Chirgwin et al.39. 20 g of nHAP was respectively incubated with 200 g of bovine serum albumin (BSA), pUC18 DNA and rat liver RNA at 37 °C for 30 min. The mixtures were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in ddH2O before the determination of the adsorption of these biomolecules with nHAP. The concentrations of BSA, DNA and RNA were measured by the absorbances at 280 nm and 260 nm.

In vivo animal experiment

The Bel-7402 human hepatocarcinoma cells were transplanted subcutaneously into the right side of the nape of every nude mouse (16–20 g) with a cell number of 1 × 107. After the tumor grew to about 1 cm3 in volume, the nude mice were killed and the tumors were extracted. The extracted tumors were transformed into cell suspensions and injected subcutaneously into the right nape of new experimental nude mice. About 0.8 cm diameter of tumors were used for the study. The nude mice bearing cancer were divided randomly into two groups (n = 13 in each group). The mice in the treated group obtained intra-tumor injection of nHAP at a dose of 0.050 g/Kg body weight every day. The mice in the control group were given equal volume of 0.9% sodium chloride solution.

Change history

27 January 2015

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

LeGeros, R. Z. Calcium phosphates in oral biology and medicine. (Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 1991).

Aoki, H. Science and medical applications of hydroxyapatite. (Japanese Association of Apatite Science, Tokyo, 1991).

Vallet-Regí, M. & González-Calbet, J. M. Calcium phosphates as substitution of bone tissues. Prog. Solid State Chem. 32, 1–31 (2004).

Meyers, M. A., Mishra, A. & Benson, D. J. Mechanical properties of nanocrystalline materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 51, 427–556 (2006).

Li, H., Khor, K. A., Chow, V. & Cheang, P. Nanostructural characteristics, mechanical properties and osteoblast response of spark plasma sintered hydroxyapatite. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 82, 296–303 (2007).

Webster, T. J., Ergun, C., Doremus, R. H., Siegel, R. W. & Bizios, R. Enhanced osteoclast-like cell functions on nanophase ceramics. Biomaterials 22, 1327–1333 (2001).

Tada, S., Chowdhury, E. H., Cho, C. S. & Akaike, T. pH-sensitive carbonate apatite as an intracellular protein transporter. Biomaterials 31, 1453–1459 (2010).

Giger, E. V., Puigmartí-Luis, J., Schlatter, R., Castagner, B., Dittrich, P. S. & Leroux, J. C. Gene delivery with bisphosphonate-stabilized calcium phosphate nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 150, 87–93 (2011).

Hideki, A., Masataka, O. & Seisuke, K. Effects of HAP-Sol on Cell Growth. Report of the institute for Medical and Dental Engineering 26, 15–21 (1992).

Li, S., Zhang, S., Chen, W. & Wen, O. Effects of hydroxyapatite ultrafine powder on colony formation and cytoskeletons of MGC-803 cell. Bioceramics 9, 225–227 (1996).

Wang, Y. F., Yan, Y. H., Cao, X. Y. & Li, S. P. Preparation and Characterization of Strontium-Containing HAP Sol and Studies on Its Effects on Cancer and Normal cells. Key Eng. Mat. 288–289, 537–540 (2005).

Yin, M. Z., Han, Y. C., Bauer, I. W., Chen, P. & Li, S. P. Effect of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on the ultrastructure and function of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. Biomed. Mater. 1, 38–41 (2006).

Yuan, Y., Liu, C. S., Qian, J. C., Wang, J. & Zhang, Y. Size-Mediated Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles in Human Hepatoma HepG2 Cells. Biomaterials 31, 730–740 (2010).

Meena, R., Kesari, K. K., Rani, M. & Paulraj, R. Effects of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles on Proliferation and Apoptosis of Human Breast Cancer Cells (MCF-7). J. Nanopart. Res. 14, 712 (2012).

Porter, A. E. Direct imaging of single-walled carbon nanotubes in cells. Nat. Nanotech. 2, 713–717 (2007).

Kandori, K., Fudo, A. & Ishikawa, T. Adsorption of myoglobin onto various synthetic hydroxyapatite particles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2, 2015–2020 (2000).

Han, Y. C., Wang, X. Y., Dai, H. L. & Li, S. P. Nanosize and surface charge effects of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on red blood cell suspensions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 4616–4622 (2012).

Lieske, J. C., Norris, R. & Toback, F. G. Adhesion of hydroxyapatite crystals to anionic sites on the surface of renal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 273, F224–F233 (1997).

Bauer, I. W., Li, S., Han, Y., Yuan, L. & Yin, M. Internalization of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in liver cancer cells. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Sci. 19, 1091–1095 (2008).

Omary, M. B., Trowbridge, I. S. & Minowada, J. Human cell-surface glycoprotein with unusual properties. Nature 286, 888–891 (1980).

Sutherland, R., Delia, D., Schneider, C., Newman, R., Kemshead, J. & Greaves M. Ubiquitous cell-surface glycoprotein on tumor cells is proliferation-associated receptor for transferring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78, 4515–4519 (1981).

Daniels, T. R., Delgado, T., Rodriguez, J. A., Helguera, G. & Penichet, M. L. The transferrin receptor part I: Biology and targeting with cytotoxic antibodies for the treatment of cancer. Clin Immunol 121, 144–158 (2006).

Daniels, T. R., Delgado, T., Helguera, G. & Penichet, M. L. The transferrin receptor part II: Targeted delivery of therapeutic agents into cancer cells. Clin Immunol 121, 159–176 (2006).

Reddy, L. H., Adhikari, J. S., Dwarakanath, B. S. R., Sharma, R. K. & Murthy, R. R. Tumoricidal effects of etoposide incorporated into solid lipid nanoparticles after intraperitoneal administration in Dalton's lymphoma bearing mice. AAPS J. 8, E254–E262 (2006).

AshaRani, P. V., Mun, G. L. K., Hande, M. P. & Valiyaveettil, S. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano 3, 279–290 (2009).

Nel, A., Mädler, L., Velegol, D., Xia, T., Hoek, E. M. V., Somasundaran, P., Klaessig, F., Castranova, V. & Thompson, M. Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano–bio interface. Nat. Materials 8, 543–557 (2009).

Hoffman, W. L. & Ilan, J. Purification on hydroxyapatite of liver ribosomes and polysomes from unfasted mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 366, 199–214 (1974).

Beland, F. A., Dooley, K. L. & Casciano, D. A. Rapid isolation of carcinogen-bound DNA and RNA by hydroxyapatite chromatography. J. Chromatography A 174, 177–186 (1979).

Nel, A., Xia, T., Mädler, L. & Li, N. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science 311, 622–627 (2006).

Poland, C. A., Duffin, R., Kinloch, I., Maynard, A., Wallace, W. A. H., Seaton, A., Stone, V., Brown, S., MacNee, W. & Donaldson, K. Carbon nanotubes introduced into the abdominal cavity of mice show asbestos-like pathogenicity in a pilot study. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 423–428 (2008).

Han, Y. C., Wang, X. Y. & Li, S. P. A simple route to prepare stable hydroxyapatite nanoparticles suspension. J. Nanopart. Res. 11, 1235–1240 (2009).

Han, Y. C., Li, S. P. & Wang, X. Y. A Novel Thermolysis Method of Colloidal Protein Precursors to Prepare Hydroxyapatite nanocrystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 44, 336–340 (2009).

Han, Y. C., Li, S. P., Wang, X. Y. & Chen, X. M. Synthesis and Sintering of Nanocrystalline Hydroxyapatite Powders by Citric Acid Sol-Gel Combustion Method. Mater. Res. Bull. 39, 25–32 (2004).

Brush, M. H., Weiser, D. C. & Shenolikar, S. Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein GADD34 targets protein phosphatase 1α to the endoplasmic reticulum and promotes dephosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1292–1303 (2003).

Boussif, O. et al. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92, 7297–7301 (1995).

Hedley, D., Rugg, C., Musgrove, E. & Taylor, I. Modulation of transferrin receptor expression by inhibitors of nucleic acid synthesis. J Cell. Physiol. 124, 61–66 (1985).

Proudnikov, D. & Mirzabekov, A. Chemical methods of DNA and RNA fluorescent labeling. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 4535–4542 (1996).

Kennes, F. Differences Between the Soluble Mitochondrial Proteins in Various Organs of the Rat. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 25, 246–247 (2005).

Chirgwin, J. M., Przybyla, A. E., MacDonald, R. J. & Rutter, W. J. Isolation of Biologically Active Ribonucleic Acid from Sources Enriched in Ribonuclease. Biochemistry 18, 5294–5299 (1979).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51002109, 39770225, 50472040), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (WUT: 2014-IV-121, 2014-VII-028) and the project supported by State Key Laboratory of Advanced Technology for Materials Synthesis and Processing (Wuhan University of Technology). Thanks for the priceless suggestions and helps from Prof. Hideki Aoki, Prof. Racquel Z. LeGeros, Prof. Clément Sanchez and Prof. Bao-Lian Su.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. started and designed the research. Y.H., X.C., L.Y., Y.Y. and T.Q. carried out the synthesis of nHAP and cell experiments. L.Y. determined the protein synthesis and enzyme activity. X.C. performed the animal test. Y.H. and Y.W. prepared the nanoparticles and identified their characteristics. S.L., Y.H., X.C., L.Y., H.D. and X.W. carried out the calculation and data analysis. S.L., Y.H., X.C. and L.Y. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Y., Li, S., Cao, X. et al. Different Inhibitory Effect and Mechanism of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles on Normal Cells and Cancer Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Sci Rep 4, 7134 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07134

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07134

This article is cited by

-

Magnetic hydroxyapatite bisphosphonate-based composites: a bone-targeting nanosystem

Emergent Materials (2023)

-

Hybrid ceramics-based cancer theranostics

Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society (2022)

-

The morphology of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis in melanoma cells and resultant anti-tumor efficiency

Nano Research (2022)

-

Cell viability of novel composite hydrogels loaded with hydroxyapatite for oral and maxillofacial bone regeneration

Odontology (2022)

-

Frequency-induced negative magnetic susceptibility in epoxy/magnetite nanocomposites

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.