Abstract

Interplay between structure and function in atomically thin crystalline nanoribbons is sensitive to their conformations yet the ability to prescribe them is a formidable challenge. Here, we report a novel paradigm for controlled nucleation and growth of scrolled and folded shapes in finite-length nanoribbons. All-atom computations on graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) and experiments on macroscale magnetic thin films reveal that decreasing the end distance of torsionally constrained ribbons below their contour length leads to formation of these shapes. The energy partitioning between twisted and bent shapes is modified in favor of these densely packed soft conformations due to the non-local van der Waals interactions in these 2D crystals; they subvert the formation of supercoils that are seen in their natural counterparts such as DNA and filamentous proteins. The conformational phase diagram is in excellent agreement with theoretical predictions. The facile route can be readily extended for tailoring the soft conformations of crystalline nanoscale ribbons and more general self-interacting filaments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

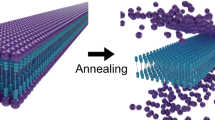

The field of atomically thin crystalline films continues to grow, both in terms of the amenable material systems and routes for processing and manipulating them. Nanoribbons of these layered 2D materials exhibit superior functional properties that are sensitive to the ribbon growth direction1, the core and edge structure and the interlayer interactions. The properties can be further tuned by the structure of the edges and the inherent coupling between the layers2. For example, Archimedean scrolls of graphene exhibit tunable transport3,4,5, supercapacitance6 and enhanced hydrogen storage7. Similarly, folds in graphene, or grafolds8, can effect semiconducting-metallic transitions9 and increase the material strength8 by localizing strain accommodation within the ribbons.

The functional properties of these ribbons both influence and are influenced by their conformations. In particular, the interplay between structure, geometry and conformation is sensitive to the extent of confinement, indicating the possibility of reversibly engineering their shapes by manipulating their end constraints. Some of the well-known shapes include twisted and helical ribbons, driven by changes in edge structure, chemistry and ribbon geometry10,11,12,13,14. These conformations are topologically invariant and since the nature of atomic-scale interactions remains fundamentally unchanged, their effect on the properties is often limited. The ability to engineer conformations with topologies that enhance non-local, interlayer interactions - scrolls, folds and knots - can dramatically modify and in some cases lead to novel properties, yet this remains a challenge due to the difficulties in manipulating them at the nanoscale.

In this article, we present a facile route to engineering topologically distinct soft conformations of nanoscale ribbons. Figure 1 depicts the scenario schematically; a finite-length nanoribbon of width w is torsionally constrained by rotating one end relative to the other and clamping the two ends. The end conditions take the form of a fixed degree of supercoiling Lk and controlled end displacement λ = z/L. The choice is motivated by the fact that, unlike the end couple (moment M and tension T), the rigid loading variables λ and Lk are more accessible and can be easily manipulated15. For a ribbon so constrained, the partitioning of the initial twist (the Twist, Tw) into energetically favorable bent shapes (the Writhe, Wr) follows from the well-known Călugăreanu-White-Fuller theorem16,17,18, Lk = Tw + Wr. The geometric partitioning is amplified by the vanishingly small thickness of the nanoribbon that favors bends and twists relative to in-plane deformations and forms the basis for the paradigm that we employ to shape these nanoribbons. The approach is bioinspired in that it is also exploited to control the properties of natural filaments such as supercoiled DNA, α-helices, elastomers and textile fibers and their yarns19,20,21,22,23,24, yet little is known about analogous conformations in these van der Waals (vdW) nanoribbons.

(top) Schematic of a suspended supercoiled nanoribbon subject to a torsional constraint.The relative rotation between the two ends sets the degree of supercoiling Lk. (bottom) The strategy used to explore the bent and twisted conformations for z < L. Magnified view of the ribbon (boxed) illustrating the ribbon and tangent vectors,  and

and  respectively, associated with the material frame used to describe the ribbon conformation.

respectively, associated with the material frame used to describe the ribbon conformation.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: we first present all-atom computations of twisted graphene nanoribbons subject to decreasing end displacements. The minimum energy conformations - consisting of scrolls, grafolds and supercoiled plectonemes - are systematically explored with varying degrees of initial twist and ribbon widths. Our results suggest a strong influence of the non-local van der Waals interactions; we validate their effect by performing similar macro-scale experiments on thin magnetic and elastomeric ribbons. A detailed theoretical analyses highlights the role of geometrical and physical parameters on the formation and stability of the conformations. We conclude with a brief discussion of the effect of these novel conformations on the nanoribbon properties and potential applications.

Results

Atomic-scale computations

The computations are performed on edge-hydrogenated zigzag GNRs as a function of ribbon supercoiling and end constraints. The stable conformations are extracted quasi-statically using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (Methods). Figure 2a and Supplementary Video 1 show the results of simulation of a GNR of length L = 110.4 nm and width w = 1.14 nm subject to a prescribed end rotation, Lk = 10. The centerline of the initial λ = 1 configuration is straight with a uniform twist density ϕ = 2π (Lk/L). The end tension T decreases with λ and at a critical point the ribbon centerline destabilizes into a helix. Each helical pitch p contributes to a full rotation of the ribbon about its centerline (boxed region in Fig. 2a) as the large in-plane to bending stiffness ratio favors developable conformations with vanishingly small Gaussian curvature25,26.

(a) Atomic configurations showing the formation and evolution of a scroll with decreasing λ = z/L in a hydrogenated GNR of length L = 110.4 nm and width w = 1.136 nm, subject to a degree of supercoiling Lk = 10. Carbon and edge hydrogen atoms are shaded gray and white, respectively. Expanded views of the boxed regions where the Writhe localizes are also shown. Some of the views are rotated to depict the details more clearly. The dotted red line in the λ = 0.93 configuration traces the helical centerline of the ribbon. (b) The change in the interaction energy of the ribbon U and the ribbon twist Tw with end displacement L − z. The degree of supercoiling Lk = 5 and Lk = 10 in the main curve and inset, respectively.

Scroll to fold transition

As λ decreases, the helix radius increases and at λ ≈ 0.93, a localizing helical instability forms, grows in length and beyond a critical size it packs itself into a dense scroll. The transition is apparent in Fig. 2 for λ = 0.89 and leads to the spontaneous formation of a multilayered scrolled at λ = 0.86. The remainder of the ribbon visibly straightens following the scroll formation due to the concomitant increase in the axial tension. The scroll axis is inclined to the original ribbon axis and it is mobile along the ribbon length. Thereafter, the scroll grows in size as the rest of the ribbon is reeled in, evident in the λ = 0.35 conformation consisting of a 6-layer scroll bounded by twisted ribbon segments. In some cases the instabilities nucleate at multiple sites, in particular at larger widths, then rapidly diffuse along the ribbon length and try to coalesce. An example is shown in Supplementary Video 2 for w = 1.6 nm and Lk = 8.25.

The inset in Fig. 2b shows the ribbon interaction energy U and the Twist Tw as a function of the imposed displacement d = L − z. The latter is extracted as the differential rotation of a material frame about the tangent  to the ribbon centerline (Supplementary Methods) and is simply one-half the number of local crossings of the two edges27,28. For Lk = 10, the energy initially decreases rapidly as the ribbon destabilizes into a helix following the removal of the pre-stretch. Further decreasing λ leads to a small jump when the scroll forms (encircled) and the energy then decreases steadily, albeit at a slower rate. Tw evolves along expected lines; we see a spontaneous decrease following scroll nucleation, also evident in the configurations. Each subsequent transition decreases the twist by ΔTw ≈ 1 and the twist density decreases by Δϕ ≈ 2π(1)/Lh, where Lh is the length of the helical phase. It is absorbed by the scroll and registers as a corresponding increase in Wr (Supplementary Figure 2). This is immediately obvious as each layer or loop within the scroll contributes to non-local self-crossing of the centerline, the very definition of Writhe18,27.

to the ribbon centerline (Supplementary Methods) and is simply one-half the number of local crossings of the two edges27,28. For Lk = 10, the energy initially decreases rapidly as the ribbon destabilizes into a helix following the removal of the pre-stretch. Further decreasing λ leads to a small jump when the scroll forms (encircled) and the energy then decreases steadily, albeit at a slower rate. Tw evolves along expected lines; we see a spontaneous decrease following scroll nucleation, also evident in the configurations. Each subsequent transition decreases the twist by ΔTw ≈ 1 and the twist density decreases by Δϕ ≈ 2π(1)/Lh, where Lh is the length of the helical phase. It is absorbed by the scroll and registers as a corresponding increase in Wr (Supplementary Figure 2). This is immediately obvious as each layer or loop within the scroll contributes to non-local self-crossing of the centerline, the very definition of Writhe18,27.

Figure 2b also shows the results for the same ribbon subject to a smaller Linking number, Lk = 5. The reduced pre-stretch lowers the critical value of λ for helix formation. The radius and the pitch length of the helix are larger and the initial energy decrease is therefore smaller. The nucleated scroll consists of a single loop that is partially double-layered with a larger inner radius. The transition leads to a significant decrease in both U and Tw. Subsequently, they decrease sharply within narrow ranges of the end displacement (encircled). Each transition is preceded by fluctuations in the scroll size, aided by decreasing λ, as the scroll overcomes the barrier for incorporation of a new layer. Initial scroll growth occurs at the expense of the helical phase and at a critical size it forms a new layer by repacking itself into a smaller size with a concomitant decrease in the twist, ΔTw ≈ 1. The transition is spontaneous since the ribbon ends terminating at the scroll must realign along the horizontal to maintain the force balance with the clamped ends. Evidently, the energy barrier for scroll formation ΔU increases with decreasing Lk and the degree of supercoiling serves as a driving force for the nucleation of the helical instability and its transformation into a scroll. Then, Lk = 10 represents a relatively high driving force with almost continuous decrease in energy with L − z. Conversely, smaller supercoiling (e. g. Lk = 5) enhances the role of fluctuations as the energy barrier is larger and the formation and growth of the scroll is discontinuous.

Scroll to fold transition

At even smaller Lk, we uncover yet another phase wherein the helical ribbon folds onto itself in a hairpin fashion. Occasionally, the multilayered segment is associated with a small twist. In some instances, we see tennis racquet like shapes consisting of coexisting folds capped by scrolls at one or both ends. We postpone the discussion of these shapes for now, but details of the evolution of these shapes are shown in Supplementary Videos 3 and 4 (w = 2.0 nm, Lk = 2.5 and w = 1.1 nm, Lk = 3.75, respectively).

Conformational phase diagram

We develop a more complete understanding of the stable phases by performing simulations with varying Lk and ribbon aspect ratios w/L (Methods). The results are shown in Fig. 3 as a conformational phase diagram, λ vs. ζ = 2πLk/L, the link density. Representative conformations are shown alongside. The initial twist is more stable at larger ζ due to the increasing pre-stretch, but in all cases small end displacements near λ ≈ 1 result in a spontaneous transition to a helix. The scrolled phase dominates for smaller values of λ, as expected. Close to the scroll-fold transition curve (ζ ≈ 0.25 at small λ), we see co-existing scrolls and multilayered folds; an example conformation is shown alongside. High values of ζ do not lead to any new phases. The response is a bit different as the larger ribbon width and pre-stretch leads to scroll formation before the ribbon relaxes out the intrinsic twist and the ribbon is stretched. The localized instability is a tightly wound helix that resembles an axially slit nanotube; an example is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

The conformational phase diagram λ vs ζ.

The co-existence lines are the set of critical points (λ, ζ) at which a new phase arises. The solid lines are the theoretically predicted critical curves. The gray, red and blue colors correspond to twist-helix, helix-scroll and scroll-fold transitions, respectively. The dotted blue line is prediction for the helix-scroll transition with a larger value of the interaction area fraction, α = 2.

Plectoneme formation

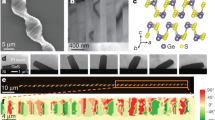

The dense scrolls and folds that we observe are rarely observed in soft ribbon-like assemblies due to the inherent self-avoidance in these solvated polymeric systems. There are exceptions, such as the formation of hairpin loops in folded β-sheet domains in proteins and in DNA/RNA which are stabilized by long-range interactions such as hydrogen bonding and specific base-pair interactions29. Clearly, the long-range vdW interactions have a decisive effect on the nature of the writhed conformations as they are comparable to the elastic energies associated with conformations i.e. bending and twist. As validation, we have repeated the computations by turning off the long-range vdW interactions. The direct comparison is shown in Figs. 4a and 4b for a GNR of length L = 110 nm and width w = 2 nm, subject to supercoiling Lk = 7.5 and an end displacement λ = 0.65. The scroll formation is suppressed (Fig. 4a) and it now forms a classical plectoneme phase that grows with decreasing λ (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Video 5).

(a–b) Atomic configurations of a GNR (a) with and (b) without long range vdW interactions. In both cases, the ribbon is subject to an end displacement of λ = 0.65 (arrows). (c–d) Results of a macroscale experiments on (c) double-sided magnetic tape and (d) simple elastic tape. The aspect ratio and the degree of supercoiling of the tapes are chosen to be the same as that of the GNRs, i.e. w/L ≈ 0.01 and Lk = 7.5.

Macroscale experiments

We test if the behavior is universal by studying the effect of rigid loading conditions on macroscale elastic tapes with comparable aspect ratios and degree of supercoiling (Methods). In the case of flexible two-sided magnetic tapes (0.076 cm thick, w = 0.5 cm, L = 50 cm), we see the nucleation of singly looped scrolls (Fig. 4c). Control experiments on non-magnetic tapes lead to the formation of classical plectonemes (Fig. 4d). The macroscale experiments serve as a useful validation, yet the dense phases are not routinely observed as the magnetic interactions are weak compared to the elastic energies. Gravity effects cannot be ignored as well. In contrast, the elastic energies stored in atomically thin ribbons are much smaller as they scale down with thickness and the effect of non-local interactions is therefore amplified. A simplified analysis on energetics of singly and doubly looped scrolls highlights the role of ratio of the bending stiffness of the GNR and the vdW interaction energy per unit area,  , on stabilization of these dense phases (Supplementary Discussion). Since the extrinsic effects are unavoidable in the macroscale tapes, we eschew their systematic study and rely on a simplified theoretical framework to further validate and analyze stability of the observed conformations.

, on stabilization of these dense phases (Supplementary Discussion). Since the extrinsic effects are unavoidable in the macroscale tapes, we eschew their systematic study and rely on a simplified theoretical framework to further validate and analyze stability of the observed conformations.

Theoretical analysis

We make contact with the displacement-controlled response by determining the energy of formation of a stable scroll within a nanoribbon subject to an end displacement parameterized by λ and then minimizing it with respect to geometric variables. We ignore the kinetics of the transient local bifurcation that precedes the nucleation of the scroll15,30,31,32 and also the effect of the clamped ends. The remainder of the ribbon is assumed to be a helical space curve as observed in the computations. We limit our analysis to moderate supercoiling and narrow inextensible ribbons, consistent with the large in-plane rigidities of these thin ribbons. Then, the energetics readily follows from the classical Love-Kirchoff framework for helical deformations of rods with appropriate modifications for the anisotropic cross-section of developable ribbons31.

The scroll removes length Ls and Linking number Lks from the helical phase. Since the conformation must conserve the total length and Linking number, lh + ls = 1 and ρh + ρs = 1 where lh = Lh/L and ls = Ls/L are the normalized lengths and ρh = Lkh/Lk and ρs = Lks/Lk are the normalized Linking numbers associated with the two phases. Ignoring the more complex configurations at the interface between the two phases (see Fig. 2a), the scroll phase stores its contribution mostly as Writhe while the Twist is distributed over the helical phase. The change in the end distance z = λL is absorbed by the helical phase. Inextensibility guarantees that the ribbon can only bend and therefore its deformed state can be completely determined from the conformation of its centerline. The helical space curve can be described in terms of its pitch p = 2πh = z/Lkh and radius  which together define the pitch angle η = h/r and the generalized curvature and torsion (Supplementary Equation 4). We simplify the geometry of the scroll by considering the limit when the scroll radius is much larger than the equilibrium interlayer distance such that the curvature variations within the multilayers can be ignored. Then, the relevant variable is its average curvature κs(ls, ρs) = 2π(Lks/Ls) = 2π(Lk/L)(ρs/ls). The elastic energy stored in the helical phase follows from Sadowsky-Wünderlich functional for narrow inextensible ribbons33,34,

which together define the pitch angle η = h/r and the generalized curvature and torsion (Supplementary Equation 4). We simplify the geometry of the scroll by considering the limit when the scroll radius is much larger than the equilibrium interlayer distance such that the curvature variations within the multilayers can be ignored. Then, the relevant variable is its average curvature κs(ls, ρs) = 2π(Lks/Ls) = 2π(Lk/L)(ρs/ls). The elastic energy stored in the helical phase follows from Sadowsky-Wünderlich functional for narrow inextensible ribbons33,34,

The scroll is stabilized by a competition between bending and interaction energies,

where uc = 1.5 eV/nm2 is the interaction energy per unit area between parallel graphene sheets. The interaction area fraction α varies as the scroll grows: α ≈ 1/4 within the single loop that nucleates at small Linking numbers (Lks = 1) while the scrolls that nucleate at larger Linking numbers are usually doubly looped (Lks = 2) such that  (Fig. 2a). As the scroll grows and becomes increasingly multilayered, α → 2. Although an approximate expression for α(ρh, Lk) can be constructed (Supplementary Equation 10), for now we ignore the variation as part of the minimization presented below.

(Fig. 2a). As the scroll grows and becomes increasingly multilayered, α → 2. Although an approximate expression for α(ρh, Lk) can be constructed (Supplementary Equation 10), for now we ignore the variation as part of the minimization presented below.

Ignoring the interface regions, the ribbon energy density (Uh + Us)/(wL) can be expressed as a functional of the form f(lh, ρh, λ) which depends on  , a dimensionless parameter that captures the effect of link density and the competing effects of the bending stiffness and the interaction energy (Supplementary Equation 12). Minimizing f with respect to the dimensionless twist ρh and length lh yields their equilibrium values as a function of the end distance λ,

, a dimensionless parameter that captures the effect of link density and the competing effects of the bending stiffness and the interaction energy (Supplementary Equation 12). Minimizing f with respect to the dimensionless twist ρh and length lh yields their equilibrium values as a function of the end distance λ,

The solution to these equations partition the conformational space into three distinct stable regimes: helix, co-existing helix and scroll and coexisting straight nanoribbon and scroll. The corresponding critical curves are plotted in Supplementary Figure 3. Below, we use these relations to quantify the formation and growth of scrolls and their transition to folds.

Scroll nucleation

For partially multilayered singly looped scrolls that nucleate at small Lk, the critical point can be expressed as  with α ≈ 1/4. Substituting in Eq. 3 yields the critical end displacement

with α ≈ 1/4. Substituting in Eq. 3 yields the critical end displacement  and the complete solution is plotted in Fig. 3 as the critical curve

and the complete solution is plotted in Fig. 3 as the critical curve  vs.

vs.  . The decrease in

. The decrease in  is in agreement with trends in the simulations. However, the quantitative agreement breaks down to some extent at large Lk; the critical point in the simulations is consistently higher due to several reasons: One, we ignore the effect of the clamped ends. Two, the long-range interactions within the transient conformations that precede the scroll nucleation are ignored in the theoretical framework. Three, the radius of the scroll is approximated as a constant and can lead to errors with increasing number of layers within the scroll. Four, the theory ignores the non-isometric deformations at the interface where the scroll transitions to a helix. The interfacial region becomes increasingly localized at large Linking numbers and can retain significant elastic energy. Finally, as mentioned earlier, the criteria for the nucleation of the doubly looped scroll must be changed to

is in agreement with trends in the simulations. However, the quantitative agreement breaks down to some extent at large Lk; the critical point in the simulations is consistently higher due to several reasons: One, we ignore the effect of the clamped ends. Two, the long-range interactions within the transient conformations that precede the scroll nucleation are ignored in the theoretical framework. Three, the radius of the scroll is approximated as a constant and can lead to errors with increasing number of layers within the scroll. Four, the theory ignores the non-isometric deformations at the interface where the scroll transitions to a helix. The interfacial region becomes increasingly localized at large Linking numbers and can retain significant elastic energy. Finally, as mentioned earlier, the criteria for the nucleation of the doubly looped scroll must be changed to  , with

, with  . The modified theoretical curve is also plotted in Fig. 3 (dashed line). The arrow in the plot indicates the approximate point at which the doubly looped scrolls become viable in the simulations. The comparison captures the effect of α on the critical point;

. The modified theoretical curve is also plotted in Fig. 3 (dashed line). The arrow in the plot indicates the approximate point at which the doubly looped scrolls become viable in the simulations. The comparison captures the effect of α on the critical point;  and

and  increase with α (Supplementary Figure 5) and the predictions are in quantitative agreement with the simulation results.

increase with α (Supplementary Figure 5) and the predictions are in quantitative agreement with the simulation results.

These effects notwithstanding, the simulations and the theoretical analysis shows that  decreases non-linearly with

decreases non-linearly with  . The origin of the decay can be understood by considering the solution in the limit

. The origin of the decay can be understood by considering the solution in the limit  (Supplementary Methods),

(Supplementary Methods),  . For β → 0 and sufficiently large Lk the decay is almost linear,

. For β → 0 and sufficiently large Lk the decay is almost linear,  . The analysis also yields the critical scroll size,

. The analysis also yields the critical scroll size,

i.e. it is proportional to the critical end distance and therefore decreases non-linearly with the corresponding link density  . The theoretical predictions are in agreement with the simulations, especially at small Lk. As an example, for Lk = 5 the size of the singly looped scroll in the simulations is R ≈ 0.3 nm (Fig. 2b) and that predicted by theory is R ≈ 0.45 nm. The predicted size of the doubly looped scroll decreases to R ≈ 0.4 nm for Lk = 10 compared to R ≈ 0.25 nm in the simulations. The computed sizes are consistently smaller, due to inaccuracies in the assumed interaction area fraction α at nucleation and related simplifying assumptions.

. The theoretical predictions are in agreement with the simulations, especially at small Lk. As an example, for Lk = 5 the size of the singly looped scroll in the simulations is R ≈ 0.3 nm (Fig. 2b) and that predicted by theory is R ≈ 0.45 nm. The predicted size of the doubly looped scroll decreases to R ≈ 0.4 nm for Lk = 10 compared to R ≈ 0.25 nm in the simulations. The computed sizes are consistently smaller, due to inaccuracies in the assumed interaction area fraction α at nucleation and related simplifying assumptions.

Scroll growth

The scroll size in the simulations increases with decreasing λ, evident in Fig. 2. The behavior is consistent with Eq. 3,

and the dependence is plotted in Fig. 5 for the GNRs geometries studied here. Quantitative agreement with the simulations is handicapped as α is assumed to be a constant. In order to fully capture this effect, we have repeated the energy minimization with varying α(ρh, Lk) (Supplementary Figure 4) and the predicted size evolution R(λ) is plotted in the inset in Fig. 5 for Lk = 5 and Lk = 10. Comparison with plots for constant α (vertical dashed lines) indicate that the rapid increase in α clearly tempers the initial scroll growth.

Dimensionless contour plot of predicted scroll size R(λ, ζ) in a GNR of length L = 110 nm and width w = 1.14 nm.

(inset) The evolution of the scroll size with end-distance L − z for Lk = 5 (red solid line) and Lk = 10 (blue solid line) with constant interaction area fraction α = 2. Theoretical predictions for varying α (dashed lines) and the size evolution extracted from the simulations (symbols) are also plotted. See text and Supplementary Methods for details.

Figure 5 also shows the size evolution in the simulations. The nucleated sizes are smaller yet the initial growth rate is in excellent agreement with the theory. Past a critical size, the scroll size begins to increase discontinuously with the addition of a new layer, slowing the growth rate. The behavior is more pronounced at lower Lk and can be clearly seen in the Lk = 5 curve. This is a result of mechanical equilibrium along the horizontal that aligns the ribbon tangents at the interface regions abutting the scroll along the clamped ends. The preferred orientation also minimizes the distortion at the interface regions. As λ decreases, the constraint forces the scrolls to grow by increasing the scroll length Ls; the decreasing end distance directly feeds the scroll by increasing its size. Past the critical point, it becomes energetically favorable for the scroll to repack by increasing the numbers of layers and therefore α (Fig. 2b). This entails sliding between the layers in the scroll. Since the interlayer interactions are weak in these vdW materials, the energy dissipation is negligible. The addition of each new layer is spontaneous once the existing scroll overcomes the energy barrier.

Scroll to fold transition

Low link densities lead to large scroll sizes that are unstable due to the small bending stiffness of the scrolled segment. Then, past another critical size, it becomes energetically favorable for the scroll to collapse into bi-/multi-layered folds. The transition is again spontaneous as unfolding requires larger end forces. Usually, the folding transition occurs well after the remainder of the ribbon has eliminated all of its twist, i.e. Lh = 0. In this regime, λ < 1 − β, the end distance Lh ∝ z and the scroll radius evolves as (Supplementary Methods)

The phenomenon is similar to the self-collapse of nanotubes where the enhanced interaction energy between the collapsed layers stabilizes the large curvatures at the folded ends35. The critical radius of a scroll that undergoes energetically favored self-collapse is

where D′ is the effective bending rigidity of the multilayered scroll and varies with the number of layers. The size is much bigger than the interlayer distance d0 such that  . The fold transition in the simulations occurs usually for multilayered scrolls (see Supplementary Video 4, Lk = 3.25) and α = 2 is a reasonable approximation for the scroll radius (Eq. 6). Additionally, since the resistance to interlayer sliding is small, the bending rigidity is simply the independent contribution of each layer and can be approximated as D′ ≈ DLks(= DLk). Then, equating Eqs. 6 and 7,

. The fold transition in the simulations occurs usually for multilayered scrolls (see Supplementary Video 4, Lk = 3.25) and α = 2 is a reasonable approximation for the scroll radius (Eq. 6). Additionally, since the resistance to interlayer sliding is small, the bending rigidity is simply the independent contribution of each layer and can be approximated as D′ ≈ DLks(= DLk). Then, equating Eqs. 6 and 7,  . The curve, plotted in Fig. 3, is in good agreement with the simulation results, especially so for large end displacements where the critical point is almost independent of λ. Then, the critical link density varies inversely with ribbon length,

. The curve, plotted in Fig. 3, is in good agreement with the simulation results, especially so for large end displacements where the critical point is almost independent of λ. Then, the critical link density varies inversely with ribbon length,  . The extent of the folded region is proportional to the critical size and it grows with decreasing λ following nucleation; the behavior is similar to the scroll growth analyzed earlier.

. The extent of the folded region is proportional to the critical size and it grows with decreasing λ following nucleation; the behavior is similar to the scroll growth analyzed earlier.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our results demonstrate a simple strategy for controlling the size and number of layers in these packed phases via geometric end constraints, thereby enabling continuous on-demand modification of their properties. The ability to prescribe their shapes offers a novel route for tuning the ribbon properties and is therefore of importance for their deployment as active elements in emerging nanoelectronic devices, electromechanical systems and nanocomposites. In particular, the higher level of control can aid the development of a novel class of non-linear nanoelectronic and NEMS devices - actuators, resonators switches - based on these vdW materials. The paradigm also applies to nanoribbons in other material systems, notably carbon nanotubes and their bundles36,37,38,39 and nanowires and nanoribbons of polar crystals such as ZnO and GaN where the non-local interactions are considerably stronger due to the presence of surface charges40,41. The interplay with end-constraints highlighted here can be employed to engineer a far richer set of conformations with their own unique set of properties - there is plenty of room at the bottom in controlling the conformations of these nanoribbons.

Methods

Atomic-scale simulations

The GNRs chosen for this study have zigzag edges. Carbon atoms at the unreconstructed zigzag edges with one missing sp2 bond are passivated with hydrogen atoms42. The simulations are performed for fixed ribbon length L = 110.4 nm and varying widths, w = 1.136 nm, 1.562 nm and 1.988 nm. The AIREBO framework is used to describe the carbon-carbon bonded interactions in the GNRs43. The vdW interactions are based on the classical 6–12 potential between graphene elements44. The potential reproduces the near-equilibrium properties of graphene; since this study is limited to soft conformations, the empirical framework is adequate for this study. The degree of supercoiling is prescribed by twisting the ribbon uniformly along its length with a twist density ϕ = 2π Lk/L. The ends are then clamped such that the end distance is equal to the contour length of the untwisted ribbon. The ribbon is relaxed using canonical MD at a T = 300°K (velocity Verlet integrator, time step 1 fs, Nosé-Hoover thermostat45,46).

Ribbon conformation

The effect of λ on the conformations is explored by decreasing the end distance quasi-statically in decrements of 2% and the energy is locally minimized using the MD algorithm. The ribbon vectors  are the generators of the developable ribbon surface (see Fig. 1). A subset of these vectors terminate at the passivating hydrogen atoms at the edges and they are monitored to dynamically generate the ribbon shape and extract Tw and Wr (Supplementary Methods).

are the generators of the developable ribbon surface (see Fig. 1). A subset of these vectors terminate at the passivating hydrogen atoms at the edges and they are monitored to dynamically generate the ribbon shape and extract Tw and Wr (Supplementary Methods).

Phase diagram

The co-existence lines represent the combination of parameters associated with the first observation of a stable new phase. The critical point for twist to helix transition is based on destabilization of the ribbon centerline; it develops a finite curvature with a well-defined pitch length smaller than the ribbon contour length. The helix to scroll transition follows from observations of stable loops. Singly looped scrolls are commonly observed at small Lk (Wr = 1, Fig. 2b) while larger supercoilings result in doubly looped scrolls (Wr = 2, Fig. 2a). Formation of both scrolls and folds results in discontinuous changes in the interaction energy U and aids in identifying the corresponding critical points.

Macroscale experiments

The magnetic tapes were cut out from double sided magnetic sheets (McMaster-Carr, ~4 kPa pull strength). The ends are gripped and rotated using clamps. The end distance is decreased at a rate ~ 10−3 s−1. The control experiments are performed on non-adhesive marking tape (3M).

References

Son, Y.-W., Cohen, M. L. & Louie, S. G. Energy gaps in graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 216803 (2006).

Braga, S. F. et al. Structure and dynamics of carbon nanoscrolls. Nano Lett. 4, 881–884 (2004).

Shi, X., Cheng, Y., Pugno, N. M. & Gao, H. A translational nanoactuator based on carbon nanoscrolls on substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 053115 (2010).

Martins, B. V. C. & Galvão, D. Curved graphene nanoribbons: structure and dynamics of carbon nanobelts. Nanotechnology 21, 075710 (2010).

Li, T., Lin, M., Huang, Y. & Lin, T. Quantum transport in carbon nanoscrolls. Phys. Lett. A 376, 515–520 (2012).

Zeng, F. et al. Supercapacitors based on high-quality graphene scrolls. Nanoscale 4, 3997–4001 (2012).

Braga, S., Coluci, V., Baughman, R. & Galvão, D. Hydrogen storage in carbon nanoscrolls: An atomistic molecular dynamics study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 441, 78–82 (2007).

Kim, K. et al. Multiply folded graphene. Phys. Rev. B 83, 245433, Jun (2011).

Xie, Y. E., Chen, Y. P. & Zhong, J. Electron transport of folded graphene nanoribbons. J. Appl. Phys. 106, 103714 (2009).

Yu, M.-F. et al. Locked twist in multiwalled carbon-nanotube ribbons. Phys. Rev. B 64, 241403 (2001).

Chuvilin, A. et al. Self-assembly of a sulphur-terminated graphene nanoribbon within a single-walled carbon nanotube. Nature Mat. 10, 687–692 (2011).

Cranford, S. & Buehler, M. J. Twisted and coiled ultralong multilayer graphene ribbons. Model. Sim. Mat. Sci. Engg. 19, 054003 (2011).

Wang, H. & Upmanyu, M. Saddles, twists and curls: shape transitions in freestanding nanoribbons. Nanoscale 4, 3620–3624 (2012).

Wang, H. & Upmanyu, M. Rippling instabilities in suspended nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 86, 205411 (2012).

Thompson, J. M. T. & Champneys, A. R. From helix to localized writhing in the torsional post-buckling of elastic rods. Proc. Roy. Soc. London A 452, 117–138 (1996).

Călugăreanu, G. Sur les classes dísotopie des noeuds tridimensionels et leurs invariants. Czechoslovak Math. J. 11, 588–625 (1961).

White, J. H. Self-linking and the Gauss integral in higher dimensions. Am. J. Math. 91, 693–727 (1969).

Fuller, F. B. The writhing number of a space curve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 68, 815–819 (1971).

Vinograd, J., Lebowitz, J., Radloff, R., Watson, R. & Laipis, P. The twisted circular form of polyoma viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 53, 1104–1111 (1965).

Boles, T. C., White, J. H. & Cozzarelli, N. R. Structure of plectonemically supercoiled DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 213, 931–951 (1990).

Strick, T. R., Allemand, J. F., Bensimon, D. & Croquette, V. Behavior of supercoiled DNA. Biophys. J. 74, 2016–2028 (1999).

Moroz, J. D. & Nelson, P. Entropic elasticity of twist-storing polymers. Macromolecules 31, 6333–6347 (1998).

Aggeli, A. et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of chiral rod-like molecules as a model for peptide β-sheet tapes, ribbons, fibrils and fibers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 11857–11862 (2001).

Ghatak, A. & Mahadevan, L. Solenoids and plectonemes in stretched and twisted elastomeric filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 057801 (2005).

Love, A. E. H. A treatise on the mathematical theory of elasticity. (Dover, New York, 1944).

Rappaport, S. M. & Rabin, Y. Differential geometry of polymer models: Worm-like chains, ribbons and fourier knots. J. Phys. A 40, 4455–4466 (2007).

Kauffman, L. H. Knots and Physics. (World Scientific, Singapore, 2001).

Dennis, M. & Hannay, J. Geometry of Călugăreanu's theorem. Proc. Roy. Soc. London A 461, 3245–3254 (2005).

Kornberg, A. & Baker, T. A. DNA replication. (W. H. Freeman & Co., New York, 1992).

Coyne, J. Analysis of the formation and elimination of loops in twisted cable. IEEE J. Oceanic Eng. 15, 385–402 (1990).

van der Heijden, G. & Thompson, J. Lock-on to tape-like behaviour in the torsional buckling of anisotropic rods. Physica D 112, 201–224 (1998). Proceedings of the Workshop on Time-Reversal Symmetry in Dynamical Systems.

Champneys, A. R. & Thompson, J. M. T. A multiplicity of localized buckling modes for twisted rod equations. Proc. Roy. Soc. London A 452, 2467–2491 (1996).

Sadowsky, M. Ein elementarer beweis für die existenz eines abwickelbaren möbiusschen bands und zurückführung des geometrischen problems auf ein variationsproblem. Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 22, 412–415 (1930).

Wunderlich, W. Über ein abwickelbares möbiusband. Monatsh. Math. 66, 276–289 (1962).

Tang, T., Jagota, A., Hui, C. & Glassmaker, N. Collapse of single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 074310 (2005).

Liang, H. Y. & Upmanyu, M. Size-dependent twisting of carbon nanotube ropes. Carbon 43, 3189–3194 (2005).

Upmanyu, M., Wang, H. L., Liang, H. Y. & Mahajan, R. Strain-dependent twist-stretch elasticity in chiral filaments. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, 303–310 (2008).

Somu, S. et al. Topological transitions in carbon nanotube networks via nanoscale confinement. ACS Nano 4, 4142–4148 (2010).

Hahm, M. G. et al. Bundling dynamics regulates the active mechanics and transport in carbon nanotube networks. Nanoscale 4, 3584–3590 (2012).

Pan, Z. W., Dai, Z. R. & Wang, Z. L. Nanobelts of semiconducting oxides. Science 291, 1947–1949 (2001).

Chen, Z., Majidi, C., Srolovitz, D. J. & Haataja, M. Tunable helical ribbons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 011906 (2011).

Lee, G. & Cho, K. Electronic structures of zigzag graphene nanoribbons with edge hydrogenation and oxidation. Phys. Rev. B 79, 165440, Apr (2009).

Brenner, D. W. et al. A second-generation reactive empirical bond order (REBO) potential energy expression for hydrocarbons. J. Phys.: Cond. Mat. 14, 783–802 (2002).

Girifalco, L. A., Hodak, M. & Lee, R. S. Carbon nanotubes, buckyballs, ropes and a universal graphitic potential. Phys. Rev. B 62, 13104–13110 (2000).

Allen, M. P. & Tildesley, D. J. Computer simulation of liquids. (Oxford University Press, North Holland, New York, 1989).

Plimpton, S. J. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comp. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Acknowledgements

The computations were performed on stAMP and Discovery supercomputing resources at Northeastern University. The study is supported by seed grant from Northeastern University (A.S.) and National Science Foundation DMR CMMT (1106214, M.U. and A.S.) and DMREF CHE (14348424, M.U.) Programs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.U. conceived the study. A.S. performed the computations. A.S. and M.U. devised and performed the macro scale experiments. H.W. and M.U. developed the theoretical frameworks. All authors analyzed the results and wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 2

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 3

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 4

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 5

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shahabi, A., Wang, H. & Upmanyu, M. Shaping van der Waals nanoribbons via torsional constraints: Scrolls, folds and supercoils. Sci Rep 4, 7004 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07004

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07004

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.