Abstract

The evolution of cooperation is a hot and challenging topic in the field of evolutionary game theory. Altruistic behavior, as a particular form of cooperation, has been widely studied by the ultimatum game but not by the dictator game, which provides a more elegant way to identify the altruistic component of behaviors. In this paper, the evolutionary dictator game is applied to model the real motivations of altruism. A degree-based regime is utilized to assess the impact of the assignation of roles on evolutionary outcome in populations of heterogeneous structure with two kinds of strategic updating mechanisms, which are based on Darwin's theory of evolution and punctuated equilibrium, respectively. The results show that the evolutionary outcome is affected by the role assignation and that this impact also depends on the strategic updating mechanisms, the function used to evaluate players' success and the structure of populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The evolution of cooperation has attracted growing interest for a long time1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Evolutionary game theory has been widely employed to address this issue8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. In previous studies, cooperation has been treated as a key mechanism to understand evolutionary processes ranging from biological systems to human society17,18,19,20,21. The effect of specific mechanisms on evolutionary outcome at the population level as well as the individual level has been well studied4,5,9,22,23,24,25,26. The emergence of flourishing cooperative behaviors among selfish individuals is the focus of intense debate within the theoretical framework of evolutionary dynamics27,28,29,30,31,32,33. The prisoner's dilemma, the snowdrift game and the public goods game are several common metaphors for studying cooperation between unrelated individuals12,34.

Altruistic behavior, in which individuals pay cost to benefit the rest of the population, can be considered a particular form of cooperation35,36,37,38. Recently, the ultimatum game has been used to examine fairness and altruistic behaviors39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. Although successful, several studies have shown that the ultimatum game has underlying motivations other than altruism and fairness48,49. Compared with the most standard ultimatum games, the dictator game50 provides a more elegant way to identify the altruistic component of behaviors. In the dictator game, there is a dictator and a responder. The dictator determines an allocation of wealth or resources, while the responder passively receives any allocations proposed by the dictator. In this way, any giving should only be attributed to altruism48,49. Therefore, the dictator game offers a huge advantage for exploring the driving influence of individual kindness in giving.

In this paper, the evolutionary dictator game is applied to model the real motivations of altruism in a population, where the dictator game is used to model the interactions between individuals and evolutionary game theory is employed to model the evolution of the system. In the evolutionary dictator game, even though there are no interactions at the stage of payoff collection, strategic imitation takes place at the moment of strategy updating. And the uncertainty of roles in dictator game leads to the interaction between the whole population and the regime for assignation of the roles. The altruism of the population and the inequality of payoff distribution are used to evaluate the evolutionary outcome. The altruism of the population is reflected by the average offer of the population, while the Gini coefficient51,52 is utilized to evaluate the inequality of payoff distribution in the whole population.

The population structure is represented by a static network where each node represents an individual. Four types of networks are employed to simulate real populations with heterogeneous structures, square lattice (SL), nearest-neighbor (NN) network, Erdos-Renyi (ER) random network53 and scale free (SF) network54. Since the the dictator game includes two roles, dictator and responder, a key mechanism is the assignation of the “dictator” role in each interaction. A degree-based role assignment43,46 is used to assign the roles and build the evolutionary dynamics of the dictator game. In the degree-based role assignment, parameter α is critical for adjusting the preference of an individual to be a dictator based on the connectivity of the individual. Positive α means that individuals with higher degrees are more likely to be the dictators, while negative α suggests the opposite. The dictator is randomly assigned if α = 0. Here, the impact of the assignation of roles on the evolutionary outcome in heterogeneous populations is assessed.

Meanwhile, four strategic updating mechanisms, namely imitate-best rule9, replicator dynamics12,55, Fermi dynamics4,56 and Bak-Sneppen dynamics57 are adopted to motivate the evolution of the population. Among these four strategic updating mechanisms, imitate-best rule, replicator dynamics and Fermi dynamics are based on Darwin's theory of evolution, where evolution takes place in a gradual and continuous manner with higher-fitness individuals reproducing and lower-fitness individuals becoming extinct during the evolutionary process. In contrast, Bak-Sneppen dynamics is based on the concept of punctuated equilibrium58, which implies that evolution occurs in intermittent bursts of strong activity separating relatively long periods of quiescence, rather than a gradual and continuous process. Within each strategic updating mechanism, two different functions for evaluating players' success, i.e., the accumulated payoff and average payoff, are considered. The present work shows that the evolutionary outcome is affected by the assignation of roles and that this impact also depends on the strategic updating mechanisms, the detailed functions for evaluating players' success and the structure of the populations. Overall, when adopting strategic updating mechanisms based on Darwin's theory of evolution, it is more effective to promote altruism and reduce the inequality of payoff distribution in heterogeneous populations if lower-degree individuals have more opportunities to act as dictator within the context of accumulated payoff. When adopting a strategic updating mechanism based on punctuated equilibrium, the results are basically opposite.

In the following, we present the results of the evolutionary dynamics of the dictator game first, discuss and compare the obtained results with other related studies and finally describe the framework of the evolutionary dictator game.

Results

To illustrate the impact of parameter α on the whole population, Fig. 1 shows the average offer p of the population as a function of parameter α if adopting different strategic updating mechanisms for various networks. Here, the average offer reflects the average degree of altruism in a population. If adopting the imitate-best rule for strategy updating (see Fig. 1(a)), the average offer is very low in SL, NN and ER networks regardless of changes in α or the use of accumulated payoff versus average payoff. On the other hand, the highly heterogeneous SF network promotes altruism in the whole population when using accumulated payoff in strategy updating and it is more effective at promoting altruism in the population if lower-degree individuals are more likely to be the dictators (i.e., α < 0). Specifically, the maximum average offers in the ER network are 0.0481 and 0.0047 for the accumulated payoff and average payoff, respectively. The SL and NN networks are indifferent to change in α because of the complete homogeneity in these networks where each node has an identical degree. In the SL network, the average offers are 0.0008 and 0.0009 for accumulated payoff and average payoff, respectively. Similarly, in the NN network, the average offers are 0.0018 and 0.0014 for the two cases. With respect to the SF network, the results are similar to the other networks if using the average payoff in strategy updating, in that the average offer p is very low. In that situation, the maximum average payoff is 0.0384 when α = −4. Using the accumulated payoff, however, the maximum average offer can reach 0.5529 when α = −3. This indicates that the high heterogeneity of network promotes altruistic behaviors in the population. Moreover, when α < 0, the maximum average offer reaches 0.5529 in the SF network. In contrast, when α > 0, the maximum average offer is 0.2397. Hence, in the SF network, the altruism of the population is enhanced if lower-degree individuals have more opportunity to act as dictators.

The average offer p of the population as a function of parameter α adopting different strategic updating mechanisms for various networks.

(a) shows the results of adopting the imitate-best rule. (b) corresponds to Fermi dynamics. (c) is the case of replicator dynamics. (d) is associated with Bak-Sneppen dynamics. In every strategic updating mechanism, the accumulated payoff and average payoff are used in strategy updating, respectively. Suffix “-A” means the accumulated payoff is used. Suffix “-a” means the average payoff is used. Each result presented is the average of 100 realizations at every α value. Other parameter: the population sizes are 40 × 40 for the SL network and 1000 for NN, ER and SF networks, the evolving generation t = 10000 and the average degree of each network  .

.

The use of Fermi dynamics and replicator dynamics for strategy updating, as seen in Fig. 1(b) and Fig. 1(c), produces robust results to support the evidence that high heterogeneity in the network promotes altruism in the population and that the lower-degree individuals acting in the role of dictators enhance altruistic behaviors more effectively than higher-degree individuals. Specifically, if adopting Fermi dynamics with accumulated payoffs, the maximum average offers are 0.4526 for α < 0 and 0.1284 for α > 0. Under the same conditions, if we adopt replicator dynamics, the maximum average offers are 0.5768 for α < 0 and 0.1451 for α > 0. In contrast, when the average payoff is used as the function for evaluating players' success, the average offers are very low for all four networks. In that situation, the heterogeneity of the network and the scheme for the assignation of roles do not promote altruism in the population and as it evolves, “selfish” individuals will spread over the whole population.

The strategic updating mechanisms adopted in Fig. 1(a), Fig. 1(b) and Fig. 1(c), i.e., imitate-best rule, Fermi dynamics and replicator dynamics, are all based on Darwin's theory of evolution and all produce similar results. Fig. 1(d) considers a special strategic updating mechanism, Bak-Sneppen dynamics, which is based on the concept of punctuated equilibrium. Using the accumulated payoff, for the SL and NN networks, the average offers are 0.4405 and 0.4466 despite the change of α. For the ER network, the average offer pER rises at a rate of 0.004 (the slope of curve ER-A in Fig. 1(d)) as α increase from -4 to 4. The minimum value pER = 0.4425 is reached while α = −4 and the maximum value pER = 0.4835 is reached while α = 4. In the SF network, the average offer pSF also rises but at the faster rate of 0.020 compared to the ER network. The minimum and maximum average offers in the SF network are 0.3724 and 0.5231, respectively. Hence, it is obvious that individuals with higher degrees acting as dictators promote altruism in heterogeneous populations. Next, let us consider the use of the average payoff in strategy updating. In this case, the average offers are 0.4405 and 0.4467 for the SL and NN networks despite the change in α. For the ER network, the minimum average offer is 0.4518 when α = 0 and the maximum average offer is 0.4692 when α = 4. For the SF network, the minimum and maximum average offers are 0.4270 when α = −4 and 0.4965 when α = 4. Thus, the results obtained using the average payoff are similar to those using accumulated payoff, that is that the altruism of heterogeneous populations is promoted if higher-degree individuals are more likely to be the dictators. But the impact of a population's heterogeneity is weakened when the average payoff is used in the process of strategy updating.

In order to further understand these results, let's reconsider Figures 1(a) (b) (c). These figures show that the population structure, except for using heterogeneous scale-free networks and accumulated payoffs, plays no significant role in promoting altruism under these situations. These unusual results are due to the game model to considered in this paper as the dictator game, unlike the prisoner's dilemma, is a constant sum game. In the prisoner's dilemma, the spatial structure (for example, the SL or NN network) can enable the cooperators to form clusters on the spatial grid and so protect themselves against exploitation by defectors. The configuration of the payoff matrix also makes cooperation-cooperation become a win-win solution for long-term interactions. In the dictator game, however, the greater quantity offered to the opponent, the less benefit gained by the player. It fails to form a cluster of altruists in the spatial structure networks. The individual making a low offer can always gain a greater payoffs (regardless of the accumulated and average payoff) so that the most selfish strategy would be imitated by all players. Therefore, the spatial structure plays no role in promoting altruism in the evolutionary dictator game. Similar results in the snowdrift game have also been reported regarding spatial structure inhibiting the evolution of cooperation59. On the other hand, these figures still conform to the previously well-established results for heterogeneous populations. Within the context of accumulated payoff, altruism, a particular form of cooperation, is promoted on a Barabasi-Albert (BA) scale-free network regardless of whether individuals with higher degrees or lower degrees are more likely to be dictators. It is consistent with previous findings that the heterogeneity of a population favors the emergence of cooperation5,6,60. In addition, the results show that altruism is inhibited on a BA scale-free network within the context of the average payoff. Some work has reported a similar conclusion that the ability of BA scale-free networks to promote cooperation disappears if the accumulated payoff is substituted with the average payoff61,62,63,64. Within the context of average payoff, the hubs are not robust to resist the invasion of defectors or selfish players; instead, the hubs facilitate the spread of defecting behaviors. In this paper, the dictator game, a highly competitive constant sum game, further restrains the cooperation.

In order to gain a better understanding of the evolutionary process, star and double star graphs12,65 as proximities of heterogeneous graphs, are employed to examine the evolutionary dynamics in the evolutionary dictator game. Detailed results and discussion are given in the Supplementary Information. For example, we give a diagrammatic sketch of the evolutionary process on the double star graph if adopting Fermi dynamics within the context of accumulated payoff, as shown in Figure 2. Initially, the offer (i.e., strategy) of each individual is generated randomly. Assume the left hub and right hub are denoted hx and hy with offers indicated by px and py. The number of leaves of these two hubs are N and M, respectively. As shown in detail in the Supplementary Information, in stage S1, the offers of the two hubs will spread over their corresponding substars whether α < 0 or α > 0. Then, the assignation of roles determines the evolutionary dynamics on the double star. When α < 0, if  , hy's offer is imitated by hx so that the left star will be invaded by the right star, shown as case 1 in Figure 2; otherwise, hy imitates hx's strategy and as a result the right star is invaded by the left star, shown as case 2 in Figure 2. This implies that an individual with a high offer has an advantage in reproducing and spreading its strategy when α < 0. Especially when hx is a very selfish individual (i.e., px is very small), the selfish strategy px is inevitably substituted by a more generous strategy py. In other words, the altruism of the population is promoted when lower-degree individuals act as the dictators. When α > 0, the left star will be invaded by the right star if

, hy's offer is imitated by hx so that the left star will be invaded by the right star, shown as case 1 in Figure 2; otherwise, hy imitates hx's strategy and as a result the right star is invaded by the left star, shown as case 2 in Figure 2. This implies that an individual with a high offer has an advantage in reproducing and spreading its strategy when α < 0. Especially when hx is a very selfish individual (i.e., px is very small), the selfish strategy px is inevitably substituted by a more generous strategy py. In other words, the altruism of the population is promoted when lower-degree individuals act as the dictators. When α > 0, the left star will be invaded by the right star if  holds, shown as case 1 in Figure 2; otherwise, the left star will invade the right star, shown as case 2 in Figure 2. This indicates that a low offer py has a potential advantage of spread when α > 0. In other words, altruism is suppressed to a certain degree when α > 0, compared to the case of α < 0. Therefore, Figure 2 confirms that altruism in a population is more effectively promoted when the lower-degree individuals have more opportunities to act as dictators using Fermi dynamics within the context of accumulated payoff.

holds, shown as case 1 in Figure 2; otherwise, the left star will invade the right star, shown as case 2 in Figure 2. This indicates that a low offer py has a potential advantage of spread when α > 0. In other words, altruism is suppressed to a certain degree when α > 0, compared to the case of α < 0. Therefore, Figure 2 confirms that altruism in a population is more effectively promoted when the lower-degree individuals have more opportunities to act as dictators using Fermi dynamics within the context of accumulated payoff.

To study the impact of parameter α on a population, apart from the average offer (altruism) of the whole population, the inequality of payoffs in the population is also a very important measure. The Gini coefficient51 measures the inequality among values of a frequency distribution. Take the levels of income in a country as an example, the more nearly equal a country's income distribution the lower its Gini coefficient (the minimum is 0.0) and the more unequal a country's income distribution, higher its Gini coefficient (the maximum is 1.0). In this paper, the Gini coefficient is treated as an index to measure the inequality of payoffs in a population. Fig. 3 shows the Gini coefficient of the population as a function of parameter α adopting different strategic updating mechanisms for various networks. Fig. 3(a) shows the results of adopting imitate-best rule as the strategic updating mechanism. Fig. 3(b) corresponds to Fermi dynamics. Fig. 3(c) is the case of replicator dynamics. Fig. 3(d) is associated with Bak-Sneppen dynamics. It is not difficult to see that the strategic updating mechanisms based on Darwin's theory of evolution (i.e., imitate-best rule, Fermi dynamics and replicator dynamics) basically display the same results, while the punctuated equilibrium-based strategic updating mechanism, the Bak-Sneppen dynamics, leads to a different outcome. Let's examine the former, taking Fermi dynamics as an example, as shown in Fig. 3(b). For SL, NN and ER networks, there is almost no difference between the use of the accumulated payoff and average payoff in strategy updating. In the SL network, the Gini coefficients are 0.2725 and 0.2721 for the cases of accumulated payoff and average payoff, respectively. In the NN network, the Gini coefficients are 0.2720 and 0.2703, respectively. In the ER network, the Gini coefficient increases with the rise of α. The minimum Gini coefficients are 0.2673 and 0.2672 which are obtained when α = −4 within the contexts of the accumulated payoff and average payoff, respectively. The maximum Gini coefficients are 0.5599 and 0.5639 both obtained when α = 4 for those two cases. In the SF network, even though there are some differences between the use of accumulated payoff and average payoff, the trends are essentially the same in that the Gini coefficients increase with the rise of α. Specifically, if the accumulated payoff is used, the minimum Gini coefficient is 0.4397 when α = −1 and the maximum Gini coefficient is 0.6911 when α = 4. If the average payoff is used, the minimum Gini coefficient is 0.1225 when α = −4 and the maximum Gini coefficient is 0.7740 when α = 4. As shown in Fig. 3(b), the use of average payoff causes more drastic fluctuation the Gini coefficient. The results of adopting the imitate-best rule and the replicator dynamics are basically same as those of the Fermi dynamics, as displayed in Fig. 3(a) and Fig. 3(c). According to these results, it is found that lower-degree individuals acting as dictators are more beneficial to reducing the inequality of payoffs in a heterogeneous population when adopting strategic updating mechanism based on Darwin's theory of evolution in the evolutionary dictator game.

The Gini coefficient of the population as a function of parameter α adopting different strategic updating mechanisms for various networks.

(a) shows the results of adopting the imitate-best rule. (b) corresponds to Fermi dynamics. (c) is the case of replicator dynamics. (d) is associated with Bak-Sneppen dynamics. In every strategic updating mechanism, the accumulated payoff and average payoff are used for strategy updating, respectively. Suffix “-A” means the accumulated payoff is used. Suffix “-a” means the average payoff is used. Each result presented is the average of 100 realizations at every α value. Other parameter: the population sizes are 40 × 40 for the SL network and 1000 for the NN, ER, SF networks, the evolving generation t = 10000 and the average degree of each network  .

.

By contrast, different results are obtained by adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics, as seen in Fig. 3(d). First, the situation of accumulated payoffs is considered. In this situation, different types of networks lead to the Gini coefficient, as the function of α, changes in various ways. The NN network has the minimum Gini coefficient of 0.1246 in comparison to the other three networks and it is constant despite changes in α. The Gini coefficient of the SL network is a little higher than that of NN network at 0.1417. For the ER network, its Gini coefficient reaches the maximum value 0.2862 when α = 2. Conversely, its minimum Gini coefficient is 0.2752 when α = −4. The gap between the maximum and minimum is around 0.01. Overall, with the increase of α, the Gini coefficient has very small fluctuation in the ER network. But it is very different in the case of the SF network, which has a maximum Gini coefficient GSF = 0.3063 when α = 0 meaning the roles of dictator are randomly allocated. With the decline of α from 0 to -4, GSF decreases at a rate of 0.005 (the slope of the left side of curve SF-A in Fig. 3(d)). Correspondingly, with the increase of α from 0 to 4, GSF decreases at a rate of 0.022 (the slope of the right side of curve SF-A in Fig. 3(d)). As a whole, the Gini coefficients when α < 0 are higher than that of α > 0, which means that having higher-degree individuals act as dictators is more effective at reducing the inequality of payoffs in a population (α > 0). Second, the situation of using average payoff in strategy updating is considered. In this situation, for SL and NN networks, the Gini coefficients are basically the same as the situation of using accumulated payoff. For the ER network, the minimum Gini coefficient is 0.2853 when α = −4 and the maximum Gini coefficient is 0.3152 when α = 3. Overall the Gini coefficients when α > 0 are higher than when α < 0 in ER network. The same result is seen in the SF network. To sum up, under the Bak-Sneppen dynamics, for heterogeneous populations, the inequality of payoffs is reduced if the higher-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators within the context of accumulated payoff and conversely, when the average payoff is used in strategy updating, the lower-degree individuals acting as dictators are more effective in reducing the inequality of payoffs.

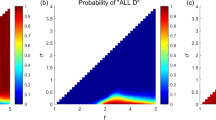

As shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 3, in ER and SF networks the evolutionary results are more diverse. To further investigate the difference between ER and SF networks, Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 show the distribution of offers D(p) in ER and SF networks when adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics and replicator dynamics where the accumulated payoff and average payoff are both considered, respectively.

The distribution of offers D(p) in ER and SF networks adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics and replicator dynamics where the accumulated payoff was used in strategy updating.

These results are a data accumulation of 100 realizations. The left column shows the results for the ER network and the right column corresponds to the SF network. (a) – (d) show the results of Bak-Sneppen dynamics and (e) – (h) show the results of replicator dynamics. Other parameter: the population size N = 1000, the evolving generation t = 10000, the average degree of each network  .

.

The distribution of offers D(p) in ER and SF networks adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics and replicator dynamics where the average payoff was used in strategy updating.

These results are a data accumulation of 100 realizations. The left column shows the results for the ER network and the right column corresponds to the SF network. (a) – (d) show the results of Bak-Sneppen dynamics and (e) – (h) show the results of replicator dynamics. Other parameter: the population size N = 1000, the evolving generation t = 10000, the average degree of each network  .

.

First, the case of accumulated payoff being used in strategy updating is considered (see Fig. 4). If adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics as the strategic updating mechanism, the distribution D(p) for the ER network has two peaks at  and

and  in the final generation when α = 0, as shown in Fig. 4(a). The extremely high offers close to 1 are almost extinct and the extremely low offers close to 0 have survived in a certain proportion. As seen in Fig. 4(b), regardless of the increase or decrease of α from 0 to 4 or −4, the distribution of offers becomes a single peak curve. When α changes from 0 to −4, the flow of offers goes from high values toward

in the final generation when α = 0, as shown in Fig. 4(a). The extremely high offers close to 1 are almost extinct and the extremely low offers close to 0 have survived in a certain proportion. As seen in Fig. 4(b), regardless of the increase or decrease of α from 0 to 4 or −4, the distribution of offers becomes a single peak curve. When α changes from 0 to −4, the flow of offers goes from high values toward  . When α changes from 0 to 4, the flow of offers goes from low values toward

. When α changes from 0 to 4, the flow of offers goes from low values toward  . These results explain the slight increase of the average offer in the ER network when α changes from −4 to 4, as shown in Fig. 1(d). In contrast, for the SF network, the asymptotic distribution of offers D(p) concentrates on [0.2, 0.6] when α = 0 as shown in Fig. 4(c). The flow of offers goes from high values toward p < 0.50 when α changes from 0 to −4 and the flow of offers goes from low values toward p > 0.50 when α changes from 0 to 4, shown in Fig. 4(d). Furthermore, the distribution of offers is more nonuniform when α = −4 than when α = 4. This explains the promotion of altruism in the whole population of the SF network as α increases (see Fig. 1(d)). If adopting replicator dynamics as the strategic updating mechanism, for the ER network, the distributions of offers D(p) are almost identical when α = 0, α = 4 and α = −4, as displayed in 4(e) and 4(f). This coincides with the results, as shown in Fig. 1(c), that the ER network does not promote the altruistic behaviors of the population if adopting strategic updating mechanism based on Darwin's theory of evolution. However, for the SF network, the values of offers range from 0.0 to 0.8 and the proportion becomes lower with the increase in offer value when α = 0 (see Fig. 4(g)). The flow of offers goes from high values toward p < 0.40 when α changes from 0 to −4 and the flow of offers goes from low values toward p > 0.30 when α changes from 0 to 4, shown as Fig. 4(h). As a result, altruism is enhanced if adopting replicator dynamics within the context of accumulated payoff.

. These results explain the slight increase of the average offer in the ER network when α changes from −4 to 4, as shown in Fig. 1(d). In contrast, for the SF network, the asymptotic distribution of offers D(p) concentrates on [0.2, 0.6] when α = 0 as shown in Fig. 4(c). The flow of offers goes from high values toward p < 0.50 when α changes from 0 to −4 and the flow of offers goes from low values toward p > 0.50 when α changes from 0 to 4, shown in Fig. 4(d). Furthermore, the distribution of offers is more nonuniform when α = −4 than when α = 4. This explains the promotion of altruism in the whole population of the SF network as α increases (see Fig. 1(d)). If adopting replicator dynamics as the strategic updating mechanism, for the ER network, the distributions of offers D(p) are almost identical when α = 0, α = 4 and α = −4, as displayed in 4(e) and 4(f). This coincides with the results, as shown in Fig. 1(c), that the ER network does not promote the altruistic behaviors of the population if adopting strategic updating mechanism based on Darwin's theory of evolution. However, for the SF network, the values of offers range from 0.0 to 0.8 and the proportion becomes lower with the increase in offer value when α = 0 (see Fig. 4(g)). The flow of offers goes from high values toward p < 0.40 when α changes from 0 to −4 and the flow of offers goes from low values toward p > 0.30 when α changes from 0 to 4, shown as Fig. 4(h). As a result, altruism is enhanced if adopting replicator dynamics within the context of accumulated payoff.

Second, the case of average payoff in strategy updating is considered to investigate the distribution of offers D(p) in ER and SF networks by adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics and replicator dynamics(see Fig. 5). Fig. 5(a) and Fig. 5(b) are similar to Fig. 5(c) and Fig. 5(d), respectively. Because the average payoff has been used in strategy updating, the difference derived from the heterogeneity of the population between ER and SF networks becomes small. For the ER network, the asymptotic distribution of offers D(p) concentrates on [0.2, 0.8] when α = 0 (see Fig. 5(a)) and it becomes slightly concentrated when α = −4 and slightly broader when α = 4 (see Fig. 5(b)). For the SF network, the asymptotic distribution of offers D(p) becomes more concentrated when α = −4 and broader when α = 4 (see Fig. 5(d)), in comparison to the ER network. Hence, the change in altruism is relatively more obvious in the SF network than in the ER network if adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics, as displayed above in Fig. 1(d). If adopting replicator dynamics as the strategic updating mechanism, as seen in Fig. 5(e), Fig. 5(f), Fig. 5(g) and Fig. 5(h), all the offers tend toward 0 whether for the ER network or for the SF network regardless of the value of α. So there is no altruism shown in either the ER or SF networks if average payoff-based replicator dynamics has been adopted for strategic updating.

The SF network is of wider concern due to its structure, which is much closer to a real population66,67,68. As found above, in the evolutionary process, the population located on a SF network exhibits more obvious altruism and other features. Therefore, in the following we study the population's evolutionary process conducted on SF networks. For the sake of comparison, two strategic updating mechanisms, the imitate-best rule and Bak-Sneppen dynamics, are considered. In the following two simulations, the accumulated payoff is used in strategy updating.

Fig. 6 shows the offer p as a function of individual degree k in a single realization conducted on SF networks where the imitate-best rule was adopted as the strategic updating mechanism and the accumulated payoff was used in strategy updating. If evolution begins with a special initial state where the offers of highest-degree individuals are set to 0.9 and the offers of other individuals are generated randomly from the interval [0, 0.5], in the final generation the offers of most individuals become 0.9 when α = −4 (see Fig. 6(a)) and the offers of all individuals become a value close to 0 when α = 4 (see Fig. 6(b)). By contrast, if evolution begins with an initial state where the offers of highest-degree individuals are set to 0.1 and the offers of other individuals are generated randomly from the interval [0.5, 1.0], in the final generation the offers of most individuals become close to 0.9 when α = −4 (see Fig. 6(c)) and the offers of all individuals become 0.1 when α = 4 (see Fig. 6(d)). These results indicate that the final distribution of offers is not determined by the higher-degree individuals, but mostly by the scheme for assignation of roles. In other words, the spread of high offers are facilitated when α = −4, while low offers are facilitated when α = 4. When α = −4, which means that lower-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators in the interactions, the individuals with higher offers can spread their strategies (i.e., offers) so that the altruism of the whole population is high in the final generation. In Fig. 6(a), the highest-degree individual has the highest offer value 0.9 so that its strategy spreads over the population and finally becomes the strategy of most individuals. In Fig. 6(c), the offer of the highest-degree individual is the lowest and hence its strategy cannot spread, while the strategies of individuals with higher offers spread over the population. In contrast, when α = 4 which means the higher-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators in the interactions, the individuals with lower offers can spread their strategies so that the altruism of the whole population is low in the final generation. In Fig. 6(d), the highest-degree individual has the lowest offer value 0.1 so that its strategy spreads over the population and finally becomes the strategy of all individuals. In Fig. 6(b), the offer of the highest-degree individual is the highest and hence its strategy cannot spread, while the strategies of individuals with lower offers can spread over the population. These results displayed in Fig. 6 conform to the conclusion derived from Fig. 1(a) that altruism is more effectively promoted when lower-degree individuals have more opportunities to be dictators when adopting the accumulated payoff-based imitate-best rule.

The offer p as a function of individual degree k in a single realization conducted on SF networks where the imitate-best rule has been adopted as the strategic updating mechanism and the accumulated payoff was used in strategy updating.

(a) and (b) are the results of one special setting where the offers of individuals having the maximum degree are set to 0.9 and the offers of other individuals are generated randomly from the interval [0, 0.5] in the initial state. (c) and (d) are the results of another special setting where the offers of individuals having the maximum degree are set to 0.1 and the offers of other individuals are generated at random from the interval [0.5, 1] in the initial state. (a) and (c) are the results for α = −4 which means the lower-degree individuals are more likely to be the dictators. (b) and (d) correspond to the results for α = 4 which means the higher-degree individuals are more likely to be the dictators. Other parameter: the population size N = 1000, the evolving generation t = 10000, the average degree of each network  .

.

Fig. 7 provides the results of a single realization of evolutionary process conducted on SF networks where Bak-Sneppen dynamics is adopted as the strategic updating mechanism and the accumulated payoff is used in strategy updating when α = −4 and α = 4. Fig. 7(a) and Fig. 7(b) show the offer as a function of individual degree k when α = −4 and α = 4, respectively. When α = −4 (see Fig. 7(a)), the lowest-degree individuals tend to offer less than 0.5 to their directly linked neighbors, while the offers of high-degree individuals are approximately random. In this situation, for the lowest-degree individuals, even facing the risk of being toppled due to exploiting other individuals, they would preferentially prevent themselves from being individual with the lowest payoff because that individual is surely eliminated in Bak-Sneppen dynamics. For the higher-degree individuals, their strategies are inessential in the interactions with lower-degree individuals so that the filtering of strategies does not work on the higher-degree individuals. Eventually, the randomness of high-degree individuals' strategies is approximately preserved.

Single realization of evolutionary process conducted on SF networks where Bak-Sneppen dynamics has been adopted as the strategic updating mechanism and the accumulated payoff was used in strategy updating when α = −4 and α = 4.

(a) and (c) show the offer and payoff as a function of individual degree k when α = −4. (b) and (d) show the offer and payoff as a function of the individual degree k when α = 4. (e) shows the Gini coefficient of the whole population as a function of generation. (f) and (g) show the average payoffs of five types of individuals, namely individuals with the minimum degree (Min), individuals whose degrees are in the upper quartile of the degree sequence where the degree sequence is an ordered sequence of all appearing degrees having deleted the repeating values (Q1), individuals whose degrees are the median of the degree sequence (Q2), individuals whose degrees are in the lower quartile of the degree sequence (Q3) and individuals with the maximum degree (Max), as a function of generation. (f) is the results for α = −4, (g) corresponds to α = 4. Other parameter: the population size N = 1000, the evolving generation t = 10000, the average degree of the SF network  .

.

When α = 4 (see Fig. 7(b)), it is found that the lowest-degree individuals offer almost any quantities to their neighbors and the offers of high-degree individuals increase approximately with the rise of the individuals' degrees. The lowest-degree individuals in this situation are always in the role of responders. Thus, their strategies are inessential in the interactions so that the strategies of the lowest-degree individuals are not filtered. Eventually, the randomness of the lowest-degree individuals' strategies is approximately preserved. Meanwhile, due to the large number of lowest-degree individuals in an SF network, their offers can be almost any quantity. Correspondingly, the high-degree individuals can usually rely on the advantage of the number of neighbors to collect a certain payoff and avoid being the poorest. Therefore, the payoffs of their neighbors are preferentially taken into consideration for high-degree individuals. Individuals with more neighbors are inclined to offer more to their neighbors in interactions to avoid being implicated. This result can be explained by a coarse-grained analysis. Assume a highest-degree individual H whose degree is kh and strategy is ph, the payoff of H is indicated by ψh = (1 − ph)kh. The payoff of the poorest individual L is indicated by  , where

, where  and

and  are the average offer of the population and the average degree of the network, respectively. Individual H must avoid being the poorest individual so that ψh > ψl, namely

are the average offer of the population and the average degree of the network, respectively. Individual H must avoid being the poorest individual so that ψh > ψl, namely  . We can obtain

. We can obtain  , where

, where  . Here,

. Here,  is the upper bound of the quantity that H can offer to its neighbors under the condition that H itself cannot be the poorest one. Under this condition, H would offer as much as possible to its neighbors to avoid being the neighbor of the poorest. More generally, the strategy that an individual can adopt is positively correlated with its degree, namely p ∝ k. Therefore, when the higher-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators, the individuals with more neighbors tend to offer more to others and the altruism of the population is promoted.

is the upper bound of the quantity that H can offer to its neighbors under the condition that H itself cannot be the poorest one. Under this condition, H would offer as much as possible to its neighbors to avoid being the neighbor of the poorest. More generally, the strategy that an individual can adopt is positively correlated with its degree, namely p ∝ k. Therefore, when the higher-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators, the individuals with more neighbors tend to offer more to others and the altruism of the population is promoted.

Figure 7(c) and 7(d) show the payoff as a function of individual degree k when α = −4 and α = 4, respectively. When α = −4, the payoffs of the individuals basically increase with the rise of their degrees and the gap between the richest and the poorest is around 40. When α = 4, there is not a positive correlation between the individuals' payoffs and their degrees and the gap between the richest and the poorest is around 10. Obviously, the polarization of payoffs is reduced when the higher-degree individuals are more likely to be the dictators (α = 4). In order to further investigate the characteristic of the distribution of payoffs under different schemes of roles assignation, Fig. 7(e) shows the Gini coefficient of the whole population as a function of generation. In the initial stage, when α = −4 or when α = 4, the Gini coefficient is relatively high due to the randomly generated strategy of each individual. Over nearly 2000 generations, the evolution of Gini coefficients tends to be stable after the initial decline. For the curve corresponding to α = −4, the Gini coefficient is around 0.3 and its evolution is steady. For the curve corresponding to α = 4, the Gini coefficient is below 0.3 and shows intermittent and dramatic ups and downs.

In order to explore the difference in the stability between these two Gini coefficient curves, Fig. 7(f) and Fig. 7(g) show the average payoffs (i.e., the average of multiple individuals' accumulated payoffs) of five types of individuals, namely individuals with the minimum degree (Min), individuals whose degrees are in the upper quartile of the degree sequence where the degree sequence is an ordered sequence of all appearing degrees without repeating values (Q1), individuals whose degrees are the median of the degree sequence (Q2), individuals whose degrees are in the lower quartile of the degree sequence (Q3) and individuals with the maximum degree (Max), as a function of generation. Fig. 7(f) shows the results for α = −4 and Fig. 7(g) corresponds to α = 4. As seen in Fig. 7(f), for these five types of individuals, the ranking of the average payoffs is constant despite the evolution. The individuals having the lowest degrees occupy the lowest average payoff and the individuals with the highest degrees occupy the highest average payoff. The higher the degree type of individuals, the more unstable the curve of average payoff. Even the curve of “Max” has an obvious fluctuation, but due to the small number of those individuals with the maximum degree, the impact on the whole population is small. Hence, the Gini coefficient curve is relatively stable when α = −4 (see Fig. 7(e)). With respect to Fig. 7(g) where α = 4, the curves of “Max”, Q3 and Q2, representing a certain number of individuals, fluctuate obviously so that the Gini coefficient curve presents instability when α = 4. In conclusion, if higher-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators, the Gini coefficient of the whole population is reduced but is not stable. In contrast, if lower-degree individuals have more opportunities to act as dictators, the Gini coefficient of the whole population is higher but stable. Overall, these results given in Fig. 7 verify the results obtained from Fig. 1(d). and Fig. 3(d) again.

Discussion

In this paper, an evolutionary dictator game model is developed to study the evolution of altruism and fairness in populations. Within the framework of the evolutionary dictator game, the impact of the assignation of roles on heterogeneous populations was studied. Parameter α controls the assignation of roles in interactions. The role of the dictator is randomly assigned if α = 0, the higher-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators if α > 0, α < 0 corresponds to the inverse side. In the evolutionary process, four strategic updating mechanisms, namely imitate-best rule, replicator dynamics and Fermi dynamics based on Darwin's theory of evolution, as well as the punctuated equilibrium-based Bak-Sneppen dynamics, have been adopted for strategy updating. The accumulated payoff and average payoff were both taken into consideration in each strategic updating mechanism. In order to measure the impact of role assignation on heterogeneous populations, the altruism of the population indicated by the average offer of the population and the inequality of the payoff distribution indicated by the Gini coefficient of population, were considered. The results are summarized as follows.

First, when the accumulated payoff is used in strategy updating for populations located on highly heterogeneous networks, lower-degree individuals with more opportunity to be dictators are more effective at promoting the altruism of the population and reducing the inequality of payoffs distribution when adopting a strategic updating mechanism based on Darwin's theory of evolution. In contrast, when adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics for strategic updating, higher-degree individuals with more opportunity to act as dictators can better promote the altruism of the population and reduce the inequality of payoffs. Second, when individual success is evaluated by average payoff, for strategic updating mechanisms based on Darwin's theory of evolution, the populations located on various homogeneous and heterogeneous networks do not show altruism whether higher-degree individuals or lower-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators. In contrast, when adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics for strategic updating, the altruistic behavior still emerges in various networks and the altruism of the population is better enhanced if higher-degree individuals have more opportunities to act as dictators. Within the context of average payoff, the inequality of payoffs distribution is relatively high in heterogeneous populations and reduction of the inequality of payoffs distribution is facilitated when lower-degree individuals are more likely to be dictators regardless of which strategic updating mechanism has been adopted.

Based on the results summarized above, a prominent and frequent finding that has been proven again is that heterogeneity always promotes cooperation in the context of accumulated payoff, as displayed in many previous studies5,6,60,69,70,71,72. In those studies, the emergence of cooperation is mainly caused by the heterogeneity. Compared with the previous studies, our model shows that not only the heterogeneity of network but also the scheme for the assignment of roles has an impact on cooperative behaviors. If adopting the imitate-best rule, replicator dynamics, or Fermi dynamics as the strategic updating mechanism, the roles assignment that gives lower-degree individuals more opportunity to be dictators is more effective at promoting cooperation. If adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics for strategy updating, the result is the opposite. This points to an important problem: Why are opposite results obtained by adopting these strategic updating mechanisms? Which one should we trust? The imitate-best rule, replicator dynamics and Fermi dynamics are based on Darwin's theory of evolution, in which biological evolution takes place in a gradual and continuous manner, while Bak-Sneppen dynamics is based on the punctuated equilibrium, which conjectures that biological evolution takes place in terms of intermittent bursts of strong activity separating relatively long periods of quiescence. These two perspectives are both supported by extant evidence. For example, the evolutionary process of a radioactive insect Pseudocubus vema shows gradual and continuous evolution and punctuated equilibrium, synchronously73,74. It is hard to completely deny either of these two kinds of strategic updating mechanisms. Each strategic updating mechanism provides a method to simulate the evolution of population. Based on these mechanisms, a comprehensive understanding of the evolution of population and cooperation can be obtained.

In addition, the Bak-Sneppen dynamics is based on the punctuated equilibrium which implies the ecology of interacting species has evolved to a self-organized critical state57,75,76. Therefore, self-organized criticality can be observed when adopting Bak-Sneppen dynamics for strategy updating. In order to verify this inference, we have performed simulations. Based on previous related study57, one method of examining the self-organized criticality of a punctuated equilibrium is to consider subsequent sequences, or avalanches, of mutations. Following Bak and Sneppen57, the size, s, of an avalanche is defined as the number of subsequent replacements at the least payoff sites below a threshold. Fig. 8 shows the distribution D(s) of avalanche sizes s in the ER and SF networks when α = −4 and α = 4, respectively, within the context of accumulated payoff. Obviously, the distribution of avalanche sizes D(s) yields a power-law distribution in each case, which qualitatively indicates that evolution occurs in a dynamical criticality. In other cases, it also presents self-organized criticality through verification.

Distribution D(s) of avalanche sizes s.

(a) is the case of α = −4 in the ER network with a threshold 0.63. (b) corresponds to α = 4 in the ER network with a threshold 0.63. (c) is the case of α = −4 in the SF network with a threshold 0.97. (d) corresponds to α = 4 in the SF network with a threshold 0.93. Other parameters: the population size N = 1000, the evolving generation t = 1000000, the average degree of each network  .

.

Apart from the strategic updating mechanisms, in the proposed model, the assignation of roles is also a concern. The dictator game reflects a widespread reality that individuals either have no power at all or full control over their own and other's success. A key point is the scheme to assign roles to determine who can become “dictators” in the interactions. The degree-based regime43 was originally designed for the evolutionary ultimatum game. A recent study43 in the evolutionary ultimatum game shows that the altruism of the population is been better promoted if the lower-degree individuals are more likely to be the proposers within the context of accumulated payoff. In another study46, the degree-based roles assignment regime has been compared with a feedback-based roles assignment regime in which the proposer who has split the money successfully would still act as the proposer with a large probability in the next round. The results show that the feedback-based mechanism is more effective in promoting fairness in the evolutionary ultimatum game46. In this paper, the ultimatum game has been substituted by the dictator game to factually reflect the real motivations of altruism. Because a consensus can always be successfully reached in the dictator game, the feedback-based mechanism is not valid. The degree-based regime vividly reflects the fact that the real world the power of each individual is determined to a great extent by his connectivity. Therefore, the degree-based roles assignment has been utilized to build the evolutionary dynamics of the dictator game. As described and analyzed above, in the evolutionary dictator game, the same conclusion was reached that the altruism of the population is better promoted if lower-degree individuals have more opportunities to act as the dictators when adopting a strategic updating mechanism based on Darwin's theory of evolution within the context of accumulated payoff. Moreover, in this paper the altruistic behavior has been further studied by adopting various strategic updating mechanisms, i.e., those based on Darwin's theory of evolution and those based on the concept of punctuated equilibrium. Many interesting results were produced and the inequality of payoffs distribution in a population has also been given attention in this study. It identifies the proper scheme for assignment of roles to better reduce the inequality of payoffs distribution under various conditions. Generally speaking, this paper addresses how cooperation emerges and in what manner cooperation can be promoted within the context of the evolutionary dictator game.

In summary, the proposed evolutionary dictator game model provides a concise framework to study the impact of roles assignation on heterogeneous populations and to explore the emergence of altruistic behaviors. In the future, it can be improved upon in many aspects. For example, the difference caused by strategic updating mechanisms based on Darwin's theory of evolution and those based on punctuated equilibrium in the evolutionary dynamics is worthy of further study. Also, the amount of wealth in our model is constant and equal to the number of links in the network. In fact, the total amount of wealth fluctuates with the evolution of society. Therefore, a model containing change in wealth needs further research. In addition, the impact of the assortative or disassortative property of the network on the evolutionary dynamics is also an attractive direction for future work.

Methods

Evolutionary dictator game

The population is made up by N individuals located on a static network. The network can be a regular one-dimensional lattice such as a nearest-neighbor (NN) network in which each individual interacts with its four nearest neighbors or a regular two-dimensional lattice such as a square lattice (SL) with periodic boundary conditions, or Erdos-Renyi (ER) random network53 or Barabasi-Albert scale free (SF) network54. NN and SL are completely homogeneous networks where every vertex has the same degree. ER and SF networks are heterogeneous networks and the SF network has a high heterogeneity.

An individual, represented as a node, plays dictator games with its linking neighbors. In the dictator game50, the first individual, called the proposer acting as a dictator, completely determines an allocation of some endowment. The second individual, called the responder, passively receives the remainder left by the proposer. In each link, the game is played only once. A degree-based regime proposed for the ultimatum game43,46 is utilized to determine who is to act as the dictator. Supposing individuals i and j are linked by an edge, the probability of i acting as the dictator is given by  , where ki is the degree of i. Obviously, positive α means that individuals with higher degrees are more likely to be the dictators. Negative α corresponds to the inverse side. If α = 0, the roles are randomly allocated. During the evolutionary process, the strategy of each individual is a real number p, 0 ≤ p ≤ 1, where p is the quantity offered to the opponent if the individual is in the role of the dictator. In each round of the game, the dictator obtains 1 − p and the other receives p. The accumulated payoff of an individual i, denoted as ψi, is the sum of payoffs obtained from all the interactions it engaged in. The average payoff of individual i is obtained by normalizing the accumulated payoff with its degree, i.e.,

, where ki is the degree of i. Obviously, positive α means that individuals with higher degrees are more likely to be the dictators. Negative α corresponds to the inverse side. If α = 0, the roles are randomly allocated. During the evolutionary process, the strategy of each individual is a real number p, 0 ≤ p ≤ 1, where p is the quantity offered to the opponent if the individual is in the role of the dictator. In each round of the game, the dictator obtains 1 − p and the other receives p. The accumulated payoff of an individual i, denoted as ψi, is the sum of payoffs obtained from all the interactions it engaged in. The average payoff of individual i is obtained by normalizing the accumulated payoff with its degree, i.e.,  .

.

Strategic updating mechanisms

At the end of each generation, once all individuals have played games with all their linked neighbors, they will update their strategies synchronously. In this paper, four updating mechanisms have been taken into consideration. In each updating mechanism, the accumulated payoff and average payoff are both used, respectively.

-

Imitate-best rule9. In this updating rule, each individual i compares its payoff with that of its neighbors. If the highest payoff of its neighbors is higher than that of i, individual i will adopt the strategy of the neighbor having the highest payoff. Otherwise, i keeps its strategy for the following generation. In this rule, the payoff can be accumulated payoff as well as average payoff.

-

Replicator dynamics12,55. Each individual i in the network compares its payoff with that of a randomly selected neighbor j and adopts the strategy of j with a probability proportional to the payoff difference. If the payoff is the accumulated payoff, the imitation probability is

where ki and kj are the degrees of i and j, respectively. If the payoff is the average payoff, the imitation probability becomes

-

Fermi dynamics4,56. Each individual i selects at random one neighbor j and adopts the strategy of j with a probability (for the context of accumulated payoff)

In the context of average payoff, the imitation probability becomes

where β is the selection intensity. In this paper β = 10.

-

Bak-Sneppen dynamics57. At the end of each generation, the individual with the lowest payoff in the population and all its immediate neighbors, however wealthy they are, are substituted by new individuals with random strategies. The payoff can be accumulated payoff as well as average payoff.

In these four strategic updating mechanisms, the imitate-best rule and Bak-Sneppen dynamics are purely deterministic, while replicator dynamics and Fermi dynamics are probabilistic updating mechanisms. The imitate-best rule, replicator dynamics and Fermi dynamics are based on Darwin's theory of evolution and have been seen as the common updating mechanisms in evolutionary game theory. Bak-Sneppen dynamics originated from the Bak-Sneppen model introduced in 1993 by Bak and Sneppen57 to describe biological species evolution. Bak-Sneppen model dynamics repeatedly eliminates the least adapted species and mutates it and its neighbors to recreate the interaction between species. This model was developed to show how self-organized criticality may explain key features of the fossil record, such as the distribution of sizes of extinction events and the phenomenon of punctuated equilibrium. The concept of punctuated equilibrium was introduce by Gould and Eldredge58 and it refers to the fact that evolution seems to take place not in a gradual and continuous manner, but rather in terms of intermittent bursts of strong activity separating relatively long periods of quiescence. As the first statistical model to display punctuated equilibrium, even though it had already been widely studied77,78,79,80, the Bak-Sneppen model has been given less attention in evolutionary game theory. Recently, Bak-Sneppen dynamics has attracted some interest for use in the study of the evolution of cooperation among competitive individuals42,81. In this paper, Bak-Sneppen dynamics puts the individual in a conflicting situation of offering less to avoid being the poorest, while offering more to avoid being implicated. As a result, the dictator would risk being toppled when exploiting other individuals.

Numerical simulations

The simulations are conducted on four types of networks which reflect the heterogeneity of the population. For NN, ER and SF networks, each network consists of 1000 nodes, i.e., the population size is 1000 and the average degree is 4. The SL network is set as a 40 × 40 regular two-dimensional lattice with periodic boundary conditions. Initially, the strategies of individuals are randomly generated in the interval [0; 1] independently. Then individuals play games with their directly linked neighbors. At the end of each generation, one of these four strategic updating mechanisms mentioned above is employed to update the population based on individual accumulated or average payoffs.

References

Axelrod, R. The Evolution of Cooperation (Basic Books, New York, 2006).

Trivers, R. Social evolution (Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Menlo Park, 1985).

Hammerstein, P. Genetic and cultural evolution of cooperation (MIT press, Cambridge, 2003).

Szabó, G. & Tőke, C. Evolutionary prisoner's dilemma game on a square lattice. Phys. Rev. E. 58, 69–73 (1998).

Santos, F. C. & Pacheco, J. M. Scale-free networks provide a unifying framework for the emergence of cooperation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 098104 (2005).

Santos, F. C., Rodrigues, J. F. & Pacheco, J. M. Graph topology plays a determinant role in the evolution of cooperation. Proc. R. Soc. B. 273, 51–55 (2006).

Nowak, M. A. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 314, 1560–1563 (2006).

Smith, J. M. Evolution and the Theory of Games (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1982).

Nowak, M. A. & May, R. M. Evolutionary games and spatial chaos. Nature 359, 826–829 (1992).

Nowak, M. A., Sasaki, A., Taylor, C. & Fudenberg, D. Emergence of cooperation and evolutionary stability in finite populations. Nature. 428, 646–650 (2004).

Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary Dynamics (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2006).

Szabó, G. & Fáth, G. Evolutionary games on graphs. Phys. Rep. 446, 97–216 (2007).

Wang, Z., Zhu, X. & Arenzon, J. J. Cooperation and age structure in spatial games. Phys. Rev. E. 85, 011149 (2012).

Novak, S., Chatterjee, K. & Nowak, M. A. Density games. J. Theor. Biol. 334, 26–34 (2013).

Ichinose, G., Saito, M., Sayama, H. & Wilson, D. S. Adaptive long-range migration promotes cooperation under tempting conditions. Sci. Rep. 3, 02509 (2013).

Wang, Z., Wang, L., Yin, Z. Y. & Xia, C. Y. Inferring reputation promotes the evolution of cooperation in spatial social dilemma games. PLoS One. 7, e40218 (2012).

Nowak, M. A. Evolving cooperation. J. Theor. Biol. 299, 1–8 (2012).

Fu, F. et al. Evolution of in-group favoritism. Sci. Rep. 2, 00460 (2012).

Rong, Z., Yang, H.-X. & Wang, W.-X. Feedback reciprocity mechanism promotes the cooperation of highly clustered scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. E. 82, 047101 (2010).

Deng, X., Wang, Z., Liu, Q., Deng, Y. & Mahadevan, S. A belief-based evolutionarily stable strategy. J. Theor. Biol. 361, 81–86 (2014).

Szolnoki, A., Wang, Z. & Perc, M. Wisdom of groups promotes cooperation in evolutionary social dilemmas. Sci. Rep. 2, 00576 (2012).

Wang, Z., Szolnoki, A. & Perc, M. Rewarding evolutionary fitness with links between populations promotes cooperation. J. Theor. Biol. 349, 50–56 (2014).

Gómez-Gardeñes, J., Campillo, M., Floría, L. M. & Moreno, Y. Dynamical organization of cooperation in complex topologies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 108103 (2007).

Szabo, G., Szolnoki, A. & Vukov, J. Selection of dynamical rules in spatial prisoner's dilemma games. Europhys. Lett. 87, 18007 (2009).

Jin, Q., Wang, L., Xia, C. & Wang, Z. Spontaneous symmetry breaking in interdependent networked game. Sci. Rep. 4, 4095 (2014).

Wang, Z., Xia, C., Meloni, S., Zhou, C. & Moreno, Y. Impact of social punishment on cooperative behavior in complex networks. Sci. Rep. 3, 3055 (2013).

Nowak, M. A., Tarnita, C. E. & Wilson, E. O. The evolution of eusociality. Nature. 466, 1057–1062 (2010).

Abbot, P. et al. Inclusive fitness theory and eusociality. Nature. 471, E1–E4 (2011).

Boomsma, J. J. et al. Only full-sibling families evolved eusociality. Nature 471, E4–E5 (2011).

Strassmann, J. E., Page Jr, R. E., Robinson, G. E. & Seeley, T. D. Kin selection and eusociality. Nature. 471, E5–E6 (2011).

Ferriere, R. & Michod, R. E. Inclusive fitness in evolution. Nature. 471, E6–E8 (2011).

Herre, E. A. & Wcislo, W. T. In defence of inclusive fitness theory. Nature. 471, E8–E9 (2011).

Nowak, M. A., Tarnita, C. E. & Wilson, E. O. Nowak et al. reply. Nature. 471, E9–E10 (2011).

Gintis, H. Game Theory Evolving (Princeton University Press, Princeton., 2000).

Trivers, R. L. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35–57 (1971).

Nowak, M. A. & Sigmund, K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 437, 1291–1298 (2005).

Fletcher, J. A. & Zwick, M. The evolution of altruism: game theory in multilevel selection and inclusive fitness. J. Theor. Biol. 245, 26–36 (2007).

Wang, Z., Kokubo, S., Tanimoto, J., Fukuda, E. & Shigaki, K. Insight into the so-called spatial reciprocity. Phys. Rev. E. 88, 042145 (2013).

Nowak, M. A., Page, K. M. & Sigmund, K. Fairness versus reason in the ultimatum game. Science. 289, 1773–1775 (2000).

Page, K. M. & Nowak, M. A. A generalized adaptive dynamics framework can describe the evolutionary ultimatum game. J. Theor. Biol. 209, 173–179 (2000).

Page, K. M., Nowak, M. A. & Sigmund, K. The spatial ultimatum game. Proc. R. Soc. B. 267, 2177–2182 (2000).

Sinatra, R. et al. The ultimatum game in complex networks. J. Stat. Mech.-Theory E. 9, P09012 (2009).

Li, Z., Gao, J., Suh, I. H. & Wang, L. Degree-based assignation of roles in ultimatum games on scale-free networks. Physica A. 392, 1885–1893 (2013).

Gao, J., Li, Z., Wu, T. & Wang, L. The coevolutionary ultimatum game. Europhys. Lett. 93, 48003 (2011).

Szolnoki, A., Perc, M. & Szabó, G. Defense mechanisms of empathetic players in the spatial ultimatum game. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 078701 (2012).

Wu, T., Fu, F., Zhang, Y. & Wang, L. Adaptive role switching promotes fairness in networked ultimatum game. Sci. Rep. 3, 01550 (2013).

Rand, D. G., Tarnita, C. E., Ohtsuki, H. & Nowak, M. A. Evolution of fairness in the one-shot anonymous Ultimatum Game. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 2581–2586 (2013).

Engel, C. Dictator games: a meta study. Exp. Econ. 14, 583–610 (2011).

Camerer, C. Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2003).

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. & Thaler, R. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. Am. Econ. Rev. 76, 728–741 (1986).

Rycroft, R. The Lorenz Curve and the Gini Coefficient. J. Econ. Educ. 34, 296–296 (2003).

Hu, H.-B. & Wang, L. The Gini coefficient's application to general complex networks. Adv. Complex Syst. 8, 159–167 (2005).

Erdos, P. & Renyi, A. On the evolution of random graphs. Publ. Math. Inst. Hungar. Acad. Sci. 5, 17–61 (1960).

Barabasi, A.-L. & Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 286, 509–512 (1999).

Taylor, P. D. & Jonker, L. B. Evolutionary stable strategies and game dynamics. Math. Biosci. 40, 145–156 (1978).

Traulsen, A., Pacheco, J. M. & Nowak, M. A. Pairwise comparison and selection temperature in evolutionary game dynamics. J. Theor. Biol. 246, 522–529 (2007).

Bak, P. & Sneppen, K. Punctuated equilibrium and criticality in a simple model of evolution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 4083–4086 (1993).

Gould, S. J. & Eldredge, N. Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology 3, 115–151 (1977).

Hauert, C. & Doebeli, M. Spatial structure often inhibits the evolution of cooperation in the snowdrift game. Nature. 428, 643–646 (2004).

Santos, F. C., Pacheco, J. M. & Lenaerts, T. Evolutionary dynamics of social dilemmas in structured heterogeneous populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3490–3494 (2006).

Masuda, N. Participation costs dismiss the advantage of heterogeneous networks in evolution of cooperation. Proc. R. Soc. B. 274, 1815–1821 (2007).

Szolnoki, A., Perc, M. & Danku, Z. Towards effective payoffs in the prisoner's dilemma game on scale-free networks. Physica A. 387, 2075–2082 (2008).

Tomassini, M., Pestelacci, E. & Luthi, L. Social dilemmas and cooperation in complex networks. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C. 18, 1173–1185 (2007).

Wu, Z. X., Guan, J. Y., Xu, X. J. & Wang, Y. H. Evolutionary prisoner's dilemma game on Barabasi-Albert scale-free networks. Physica A. 379, 672–680 (2007).

Santos, F. C., Santos, M. D. & Pacheco, J. M. Social diversity promotes the emergence of cooperation in public goods games. Nature. 454, 213–216 (2008).

Boccaletti, S., Latora, V., Moreno, Y., Chavez, M. & Hwang, D. U. Complex networks: Structure and dynamics. Phys. Rep. 424, 175–308 (2006).

Newman, M. E. The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Rev. 45, 167–256 (2003).

Wei, D. J. et al. Box-covering algorithm for fractal dimension of weighted networks. Sci. Rep. 3, 03049 (2013).

Zimmermann, M. G. & Eguiluz, V. M. Cooperation, social networks and the emergence of leadership in a prisoner's dilemma with adaptive local interactions. Phys. Rev. E. 72, 056118 (2005).

Moreira, J. A., Pacheco, J. M. & Santos, F. C. Evolution of collective action in adaptive social structures. Sci. Rep. 3, 01521 (2013).

Souza, M. O., Pacheco, J. M. & Santos, F. C. Evolution of cooperation under N-person snowdrift games. J. Theor. Biol. 260, 581-588 (2009).

Santos, M. D., Pinheiro, F. L., Santos, F. C. & Pacheco, J. M. Dynamics of N-person snowdrift games in structured populations. J. Theor. Biol. 315, 81–86 (2012).

Kellogg, D. E. The role of phyletic change in the evolution of Pseudocubus vema (Radiolaria). Paleobiology. 1, 359–370 (1975).

Bak, P. How nature works: the science of self-organized criticality (Copernicus Press, New York, 1996).

Bak, P., Tang, C. & Wiesenfeld, K. Self-organized criticality: an explanation of 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 381–384 (1987).

Bak, P. & Chen, K. Self-organized criticality. Sci. Am. 264, 46 (1991).

Tamarit, F. A., Cannas, S. A. & Tsallis, C. Sensitivity to initial conditions in the Bak-Sneppen model of biological evolution. Eur. Phys. J. B. 1, 545–548 (1998).

Boettcher, S. & Percus, A. Nature's way of optimizing. Artif. Intell. 119, 275–286 (2000).

Meester, R. & Sarkar, A. Rigorous self-organized criticality in the modified Bak-Sneppen model. J. Stat. Phys. 149, 964–968 (2012).

Xiao, S. S. & Yang, C. B. (2012).Critical fluctuations in the Bak-Sneppen model. Eur. Phys. J. B. 85, 1–5 (2012).

Park, S. & Jeong, H. C. Emergence of cooperation with self-organized criticality. J. Korean. Phys. Soc. 60, 311–316 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The work is partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61174022), Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (Grant No. 20131102130002), R&D Program of China (2012BAH07B01), National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (Grant No. 2013AA013801), the open funding project of State Key Laboratory of Virtual Reality Technology and Systems, Beihang University (Grant No.BUAA-VR-14KF-02), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. XDJK2014D034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.D. and Y.D. designed and performed research. X.D. wrote the paper. Q.L. and R.S. performed the computation. Q.L., R.S. and Y.D. analyzed the data. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, X., Liu, Q., Sadiq, R. et al. Impact of Roles Assignation on Heterogeneous Populations in Evolutionary Dictator Game. Sci Rep 4, 6937 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06937

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06937

This article is cited by

-

A reinforcement learning approach to explore the role of social expectations in altruistic behavior

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The dynamics of human behavior in the public goods game with institutional incentives

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

A novel framework of classical and quantum prisoner’s dilemma games on coupled networks

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Newborns prediction based on a belief Markov chain model

Applied Intelligence (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.