Abstract

Four nanoporous carbons prepared by direct carbonization of non-permanent highly porous MOF [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n without any additional carbon precursors. The carbonization temperature plays an important role in the pore structures of the resultant carbons. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface areas of four carbon materials vary from 464 to 1671 m2 g−1 for different carbonization temperature. All the four carbon materials showed a mesoporous structure centered at ca. 3 nm, high surface area and good physicochemical stability. Hydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide sorption measurements indicated that the C1000 has good gas uptake capabilities. The excess H2 uptake at 77 K and 17.9 bar can reach 32.9 mg g−1 and the total uptake is high to 45 mg g−1. Meanwhile, at 95 bar, the total CH4 uptake can reach as high as 208 mg g−1. Moreover the ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) prediction exhibited exceptionally high adsorption selectivity for CO2/CH4 in an equimolar mixture at 298 K and 1 bar (Sads = 27) which is significantly higher than that of some porous materials in the similar condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoporous carbon materials have gained much attention owing to their high surface area, narrow pore size distribution and good thermal and chemical stability. These characteristics allow porous carbon can be utilized for a variety of applications such as adsorbents, catalyst supports, electrode materials and so on1,2,3,4,5,6. Several synthetic methods were explored to prepare highly porous carbons and control their pore structures, including pyrolysis followed by physical or chemical activation of organic precursors, carbonization of polymeric aerogels, template synthetic procedures, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and laser ablation1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Using zeolites and mesoporous silicas such traditional inorganic materials as a template, ordered microporous and mesoporous carbons have been successfully prepared in recent years by the nanocasting technique4,5,15,16. The pore structures of carbons obtained by nanocasting with template approach can be further tuned by physical or chemical activation, although it is slightly complex to remove the template and unsuited for mass production.

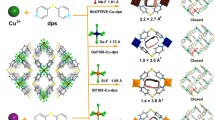

On the other hand, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) or porous coordination polymers (PCPs), which are newly emerging porous materials with multiple functionalities, have attracted much attention mainly because of their high surface area, tunable porosity and wide potential applications in gas storage, separation, catalysis and sensing17,18,19,20. Porous MOFs are usually thermally robust and have various pore sizes suitable for small molecules to access. Therefore, they have been considered as templates to construct nanoporous carbon materials. Xu et al. used the MOFs as templates for synthesis of nanoporous carbon materials for the first time21. Under the atmosphere of furfruyl alcohol (FA) vapor, they have successfully introduced FA into the micropores of MOF-5 followed by polymerization and carbonization to prepare nanoporous carbons. Since then, some related works were published in succession22,23,24,25,26,27. Recently, some other groups also have reported that nanoporous carbon can be obtained by a simpler method-direct carbonization of MOFs without any additional carbon precursors28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Though such reported carbon materials have broad pore size distributions and the carbonization condition was not clearly understood, this approach has worked pretty well for preparing porous carbons. The current MOFs template used for porous carbon usually has permanent porosities. However, many MOFs only have an apparent porosity which frameworks may be ruined in the activation process and how to use these pore structures in MOFs with non-permanent porosities are always a challenge. Recent studies show that even nonporous Zn-based MOFs could also be applied to prepare highly porous carbons, which opens up the way for the use of nonporous MOFs32,35. For example, [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n is isostructure with HKUST-1 [Cu3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n which is one of the most famous MOFs36. Though [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n is also highly porous from the point of crystallography, the framework will collapse during activation. Here, we reported using direct-method carbonization to transform non-permanent highly porous MOF [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n into stable nanoporous carbons with high surface areas. These carbon materials exhibited a large gas storage capacity and exceptionally high adsorption selectivity for CO2/CH4. We carefully investigated the structure of the porous carbons, the effect of the carbonization temperature on its gas adsorption properties.

Results

The presence of nanopores in the obtained samples was confirmed by nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements (Figure 1a). Nitrogen isotherms were also carried out to evaluate the specific surface areas and pore-size distribution of the C800, C1000, C1200 and C1400 samples. The general shape of the N2 sorption isotherms for four samples indicates the existence of different pore sizes varying from micropores to mesopores. At low relative pressure area (P/P0 < 0.1), the curves showed a drastic uptake suggesting the presence of micropores. Hysteresis between the adsorption and desorption curves for all the samples reveal the presence of mesopores. Meanwhile, slight uptakes at high relative pressure near to 1.0 point indicating that existence some macropores, which probably forming between particles. All the samples exhibited very similar pore size distribution with a peak centering at ca. 3 nm (Figure 1b). Here it should be pointed out that the surface area of the original crystals cannot be obtained because the framework of original crystals may collapse during the activated process, whereas high surface area is obtained when the crystals deal with high temperature carbonization. This method-direct carbonization provided a meaningful approach for solving the problem of effective use of unstable porous crystal materials.

The high surface areas of the obtained carbon materials prompted us to study their gas-uptake capacity, especially that for hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane. As is shown in Figure 2a, the hydrogen adsorption isotherms of all the obtained carbons measured at 1 bar and liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K) by the volumetric method. All the isotherms do not display any hysteresis, indicating that the uptake of hydrogen by the nanoporous carbon materials is reversible. The hydrogen uptake capacity of C1000 reached 20.1 mg g−1, which is comparable with HKUST-1 (the amount absorbed 25.4 mg g−1). From the pore size distribution analysis, the micropore pore volume can be regarded as facilitating the hydrogen uptake. The nearly close micropore distribution of three samples C1000, C1200 and C1400 can also explain their close adsorption quantity of hydrogen uptakes. The isosteric heat of adsorption for H2 was obtained by applying the virial-type expression of the Clausius-Clapeyron equation to the isotherms measured at 77 and 87 K. The isosteric heat of adsorption at low coverage is around 8.4 kJ mol−1 for C1000, decreasing slightly to 5.3 kJ mol−1 at higher coverage (Figure 2b). This value of the heat of adsorption at low coverage is higher than that of HKUST-1 (~7 kJ mol−1), silica gel (7.3 kJ mol−1) and other microporous carbons after various chemical activations (7–7.5 kJ mol−1)37,38. The high enthalpy could be attributed to the small size of the pore.

H2 or CH4 is a good candidate as an on-board fuel, however it lacks a reliable way of storage. In order to further evaluate the gas storage capacity of C1000, high-pressure adsorption capacities of H2 and CH4 of C1000 were measured at 77 K and 298 K, respectively (Figure 2b and 3c). As is shown in Figure 2b, the excess H2 uptake at 77 K and 17.9 bar can reach 32.9 mg g−1 and the total uptake is high to 45 mg g−1 which can compare to that of many porous carbon materials1,39,40. The saturation excess CH4 uptake of C1000 at 298 K and 95 bar is up to 135.6 mg g−1, 11.9 wt.% (HKUST-1 15.7 wt.% at 75 bar and 303 K)41. Meanwhile, at 95 bar, the total CH4 uptake can reach as high as 208 mg g−1 (17.2 wt%). Though the CH4 uptake is still below the target of 400 mg g−1 in an ANG fuel storage system for passenger vehicle usage, it is one of the best methane storage materials based on porous materials so far40,42.

In addition, the CO2 and CH4 were also measured at 298 K, respectively. As shown in Figure 3a and 3b, the maximum adsorbed amount of CO2 and CH4 of C1000 up to 163 mg g−1 and 28 mg g−1 at 298 K and 1 bar, respectively and the enormous difference of uptakes shows that the C1000 should have CO2/CH4 separation performance. The significantly high CO2/CH4 separation selectivity demonstrates the promise of C1000 for practical CO2/CH4 separation at room temperature. The CO2/CH4 adsorption selectivity for binary mixtures can be calculated by the IAST which has been successfully applied to predict binary gas mixture separation for the porous carbon, zeolites, MOFs and porous polymers. As can be seen from Figure 4, the adsorption selectivities of C1000 for CO2/CH4 as different rations were estimated from the experimental single-component isotherms which were fitted to a single-site Langmuir-Freundlich model. Overall C1000 showed increasing CO2/CH4 selectivities with increasing pressure. For example, C1000 exhibited exceptionally high adsorption selectivity for CO2/CH4 in an equimolar mixture at 298 K and 1 bar (Sads = 27) which is much higher than that of some porous materials at the similar condition43,44,45, such as PPN-1 (Sads = 4.5)46, UTSA-25 (Sads = 12.5)47, Zn3(OH)(p-CDC)2.5 (Sads = 5 ~ 17)48, OMC (Sads = 3.4)49. We attributed much higher quadrupole moment of CO2 to the high adsorption selectivity for CO2/CH4. The interactions between CO2 molecule and carbon are stronger than CH418. Moreover, we also investigated the heat of adsorption of CH4 and CO2 in the temperature range between 298 K and 273 K. The isosteric heat of adsorption of CO2 at low coverage is around 20.7 kJ mol−1 for C1000, decreasing slightly to 18.8 kJ mol−1 at higher coverage. For the heat of adsorption of CH4 at low coverage is around 17.4 kJ mol−1 for C1000, decreasing slightly to 16.3 kJ mol−1 at higher coverage (Figure 3d). In terms of heat of adsorption, CO2 is higher than CH4. This result can also account for the high adsorption selectivity for CO2/CH4. Both values of CO2 and CH4 are comparable with several commercially activated carbons (16–25 kJ mol−1 for CO2 and 16–20 kJ mol−1 for CH4 at zero loading, respectively)50,51.

Discussion

The obtained nanoporous carbon materials exhibited high gas storage abilities and adsorption selectivity prompted us to study its pore structures. Powder X-ray diffraction patterns (PXRD) of C800, C1000, C1200 and C1400 were presented in Figure 5a. All the sharp peaks were observed in sample C800 that could be assigned to the ZnO species. To obtain pure carbon materials, it is necessary washing with strong acids in the usual method. On the other hand, this undoubtedly needs an additional step of washing process. In previous reports, when the temperature higher than 800°C, ZnO was reduced to metallic Zn species and the carbon matrix materials obtained as long as the temperature higher the boiling point of metallic Zn (908°C)22,52. Based on this strategy, the much higher carbonization temperature was used, which up to 1000°C, 1200°C and 1400°C. The results are the same as expected, for the samples of C1000, C1200 and C1400, the peaks of ZnO species from PXRD cannot be found instead by two broad peaks at around 24 and 44° that were assigned to the carbon (002) and (101) diffractions, respectively. Also, the Energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) measurements were performed to further confirm the removal of Zn from carbon matrix. The EDS results indicate that the percentage of Zn present in the carbon matrix is almost negligible when the temperature up to 1000°C (that is, less than <1%; Figure S1, Table S1). From the FTIR spectra analysis (Figure S2), a weak peak located at 1120 cm−1 can be attributed to the C-O vibration. Zn-O vibration was disappeared in C1000, C1200 and C1400, however, which is obvious in C800 nearby 440 cm−1. In addition, from the (002) peaks in the PXRD profiles, the degree of graphitization of the C1000, C1200 and C1400 samples could be low53.

In order to further investigate the details of structure on carbon materials, Raman spectra and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were performed. Raman spectra for the C1200 sample are shown in Figure 5b. The spectra displayed D and G bands at 1333 and 1588 cm−1, respectively. Generally speaking, the appearance of the D peak corresponds to the presence of a disordered carbon structure. The relative ratios of the G bands to the D bands (IG/ID) reveal the crystallization degree of graphitic carbon. The appearance of the obvious D bands indicated that graphene sheets were not well developed and the carbon structure contained both graphitic and disordered carbon atoms28,29,30,31. In addition, from the high resolution images observations (Figure 5c and 5d), randomly assembled the nanometer-sized sheets were observed in the obtained carbon materials and the disordered graphitic layers suggest a relatively low degree of graphitization, revealing a low concentration of parallel single layers in the obtained carbon material, which in agreement with the PXRD and Raman spectra results mentioned above29.

The BET surface area and pore size distributions of all the samples are shown in the Table 1. From the table analysis, the pore structures of obtaining carbons vary depending on the treatment conditions. The pore-size distribution calculated from DFT was widely distributed from 1 to 4 nm. The BET surface area and total pore volume of C800 were found to be 464 m2 g−1 and 0.25 cm3 g−1, respectively, which are much lower than other three samples. This may cause by ZnO species remained in the obtained carbon. However, the highest BET surface area of 1671 m2 g−1 and corresponding pore volume 1.01 cm3 g−1 is obtained for the sample of C1200, suggesting that the carbonization temperature plays an important role in the resultant carbon. Recently, Kim32 and Kurungot35 have found that the porosity of the carbon materials depends linearly on the Zn/C ratio of MOF precursors and even the nonporous MOF could also generate highly nanoporous carbons. The removal of Zn from carbons is critical for acquiring high BET surface area. During the carbonization process(≥900°C),ZnO was reduced to Zn and vaporized away along with the N2 flow, accompany by considerable C and O mass-loss which evolution of CO and CO2, leaving a more defective or hollow carbon network. This process acts as a simple self-activation for the carbon54. This observation may account for the high improvement of the BET surface area from C800 to C1200. It is noticeable that the BET surface area of C1200 is even higher than its isostructural crystal (1507 m2 g−1 for HKUST-1) reported before37. Meanwhile, the data in the table also reveal the complication of the temperature effect on the carbon structures. The BET surface area increased with the temperature rose. But when the temperature reached 1400°C, it is reduced. This may be due to the higher temperature destroyed the structure of the pores.

In conclusion, we have successfully employed a method—direct carbonization of non-permanent highly porous MOF [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n without any additional carbon precursors to prepare porous carbon materials, which exhibits high specific surface areas, mainly with mesopores, significant gas uptake capabilities in both low-pressure and high-pressure environments as well as exceptionally high adsorption selectivity for CO2/CH4. The carbonization temperature plays an important role in specific surface area, pore size distribution and gas uptake. The carbon materials obtained at 1200°C have the highest specific surface areas (SBET = 1671 m2 g−1). The C1000 has the best gas uptake capacities and exhibited exceptionally high adsorption selectivity for CO2/CH4 in an equimolar mixture at 298 K and 1 bar (Sads = 27). Combined with gas uptake ability and physicochemical stability, these carbon materials are very promising for the clean energy storage and gas separation. This carbonization method can be easily extended to the preparation of nanoporous carbon materials by using the other non-permanent highly porous MOFs.

Methods

Sample preparation

Chemicals

All chemicals were obtained from commercial vendors and used without further purification unless otherwise specified.

Preparation of MOF [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n. [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n crystals were prepared by our modified method according to a previous report36. A mixture of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.2975 g, 1 mmol), 1, 3, 5-benzenetricarboxylic acid (0.2100 g, 1 mmol), 4, 4′-bipyridine (0.0156 g, 0.1 mmol) and N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, 12 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The solution was filled in a 25 mL vial. The vial was capped tightly, placed in an oven and heated to 80°C for 48 h to yield large colorless blocky crystals. After cooling, the crystals were filtered, washed with DMF three times and immersed in dried DMF for further experiments.

Preparation of nanoporous carbon

The prepared [Zn3(BTC)2·(H2O)3]n crystals were put into a ceramic boat. Then the prepared MOF was transferred to a tube furnace and heated under a nitrogen gas flow from room-temperature to 800°C, 1000°C, 1200°C, 1400°C with a heating rate of 5°C min−1 to pyrolyze the organic species. After the temperature reached the goal settings, it was maintained for 5 h. After that, the material was then cooled to room temperature with a cooling rate of 5°C min−1. Finally, the MOFs calcined at 800°C, 1000°C, 1200°C and 1400°C for 5 h afford the nanoporous carbon materials designated as C800, C1000, C1200 and C1400, respectively.

Measurements

The nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements were carried out at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K) by using an automatic volumetric adsorption equipment (Micromeritics, ASAP2020). PXRD patterns were recorded on a MiniFlex II spectrometer using Cu Kα radiation. TEM images were obtained using a JEOL JEM-2010 microscope. Raman data were obtained on a LabRAM Aramis (Laser Confocal Micro-Raman Spectroscopy) spectrometer using a 532 nm wavelength. FT-IR spectra were collected on a VERTEX 70 spectrometer (using KBr pellets). EDS was performed using a JSM 6700 microscope. The high temperature pyrolysis reaction was performed on a tube furnace (KTL 1600, Nanjing NanDa Instrument Plant). Low pressure (<800 torr) gas sorption isotherms was performed using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 surface area and pore size analyzer. Pore size distribution data were obtained from the N2 sorption isotherms based on the DFT model on the Micromeritics ASAP 2020 software package (assuming slit pore geometry). An ultra-high purity (UHP, 99.999% purity) grade of N2, H2, CH4 and CO2 gases was used throughout the adsorption experiments. Prior to the measurements, all the samples were degassed at 120°C for 10 h to remove the adsorbed impurities. High pressure excess adsorption of H2 and CH4 were performed using a Hydrogen Storage Analyser (HTP1-V, Hiden) at 77 K (liquid nitrogen bath)or 298 K (room temperature). Prior to the measurements, the sample was degassed at 120°C for 10 h to remove the adsorbed impurities. The hydrogen isosteric heat of sorption was calculated as a function of the hydrogen uptake by comparing the adsorption isotherms at 77 K and 87 K. The data were modeled with a virial-type expression composed of parameters ai and bi (Equation 1) and the heat of adsorption (Qst) was then calculated from the fitting parameters using Equation 2, where p is the pressure, N is the amount adsorbed, T is the temperature, R is the universal gas constant and m and n determine the number of terms required to adequately describe the isotherm. In order to compare the efficacy of C1000 for CO2/CH4 separation, we used the IAST of Myers and Prausnitz55 along with the pure component isotherm fits to determine the molar loadings in the mixture for specified partial pressures in the bulk gas phase. The measured experimental data on pure component isotherms for CO2 and CH4, in terms of excess loadings, were first converted to absolute loading using the Peng-Robinson equation of state for estimation of the fluid densities. The pore volume of C1000 used for this purpose was 0.96 cm3 g−1. The absolute component loadings at 298 K were fitted with either a single-site Langmuir-Freundlich model (Equation 3), where a is saturation capacity and b and c are constant.

References

Wang, H. L., Gao, Q. M. & Hu, J. High Hydrogen Storage Capacity of Porous Carbons Prepared by Using Activated Carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 7016–7022 (2009).

Xia, Y. D., Mokaya, R., Walker, G. S. & Zhu, Y. Q. Superior CO2 Adsorption Capacity on N-doped, High-Surface-Area, Microporous Carbons Templated from Zeolite. Adv. Energy Mater. 1, 678–683 (2011).

Yang, R. T. & Wang, Y. H. Catalyzed Hydrogen Spillover for Hydrogen Storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4224–4226 (2009).

Itoi, H., Nishihara, H., Kogure, T. & Kyotani, T. Three-Dimensionally Arrayed and Mutually Connected 1.2 nm Nanopores for High-Performance Electric Double Layer Capacitor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1165–1167 (2011).

Liang, C. D., Li, Z. J. & Dai, S. Mesoporous carbon materials: Synthesis and modification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3696–3717 (2008).

Hu, B., Wang, K., Wu, L. H., Yu, S. H., Antonietti, M. & Titirici, M. M. Engineering Carbon Materials from the Hydrothermal Carbonization Process of Biomass. Adv. Mater. 22, 813–828 (2010).

Zhang, F. Q. et al. A facile aqueous route to synthesize highly ordered mesoporous polymers and carbon frameworks with Ia(3)over-bard bicontinuous cubic structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13508–13509 (2005).

Yang, H. F. & Zhao, D. Y. Synthesis of replica mesostructures by the nanocasting strategy. J. Mater. Chem. 15, 1217–1231 (2005).

Lu, A. H. & Schuth, F. Nanocasting: A versatile strategy for creating nanostructured porous materials. Adv. Mater. 18, 1793–1805 (2006).

Zheng, B., Lu, C. G., Gu, G., Makarovski, A., Finkelstein, G. & Liu, J. Efficient CVD growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes on surfaces using carbon monoxide precursor. Nano Lett. 2, 895–898 (2002).

Thess, A. et al. Crystalline ropes of metallic carbon nanotubes. Science 273, 483–487 (1996).

Horikawa, T., Hayashi, J. & Muroyama, K. Controllability of pore characteristics of resorcinol-formaldehyde carbon aerogel. Carbon 42, 1625–1633 (2004).

Wu, D. C., Fu, R. W., Dresselhaus, M. S. & Dresselhaus, G. Fabrication and nano-structure control of carbon aerogels via a microemulsion-templated sol-gel polymerization method. Carbon 44, 675–681 (2006).

Matsuoka, T., Hatori, H., Kodama, M., Yamashita, J. & Miyajima, N. Capillary condensation of water in the mesopores of nitrogen-enriched carbon aerogels. Carbon 42, 2346–2349 (2004).

Xia, Y., Yang, Z. & Mokaya, R. Templated nanoscale porous carbons. Nanoscale 2, 639–659 (2010).

Zhou, L. et al. Easy synthesis and supercapacities of highly ordered mesoporous polyacenes/carbons. Carbon 44, 1601–1604 (2006).

Yuan, D. Q., Zhao, D., Sun, D. F. & Zhou, H. C. An Isoreticular Series of Metal-Organic Frameworks with Dendritic Hexacarboxylate Ligands and Exceptionally High Gas-Uptake Capacity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5357–5361 (2010).

Li, J. R., Sculley, J. & Zhou, H. C. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Separations. Chem. Rev. 112, 869–932 (2012).

Ma, L. Q., Abney, C. & Lin, W. B. Enantioselective catalysis with homochiral metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1248–1256 (2009).

Chen, B. L., Wang, L. B., Zapata, F., Qian, G. D. & Lobkovsky, E. B. A luminescent microporous metal-organic framework for the recognition and sensing of anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6718–6719 (2008).

Liu, B., Shioyama, H., Akita, T. & Xu, Q. Metal-organic framework as a template for porous carbon synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5390–5391 (2008).

Liu, B., Shioyama, H., Jiang, H. L., Zhang, X. B. & Xu, Q. Metal-organic framework (MOF) as a template for syntheses of nanoporous carbons as electrode materials for supercapacitor. Carbon 48, 456–463 (2010).

Hu, J. A., Wang, H. L., Gao, Q. M. & Guo, H. L. Porous carbons prepared by using metal-organic framework as the precursor for supercapacitors. Carbon 48, 3599–3606 (2010).

Jiang, H. L. et al. From Metal-Organic Framework to Nanoporous Carbon: Toward a Very High Surface Area and Hydrogen Uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11854–11857 (2011).

Radhakrishnan, L., Reboul, J., Furukawa, S., Srinivasu, P., Kitagawa, S. & Yamauchi, Y. Preparation of Microporous Carbon Fibers through Carbonization of Al-Based Porous Coordination Polymer (Al-PCP) with Furfuryl Alcohol. Chem. Mater. 23, 1225–1231 (2011).

Chaikittisilp, W., Ariga, K. & Yamauchi, Y. A new family of carbon materials: synthesis of MOF-derived nanoporous carbons and their promising applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 14–19 (2013).

Hu, M. et al. Direct synthesis of nanoporous carbon nitride fibers using Al-based porous coordination polymers (Al-PCPs). Chem Commun 47, 8124–8126 (2011).

Chaikittisilp, W. et al. Nanoporous carbons through direct carbonization of a zeolitic imidazolate framework for supercapacitor electrodes. Chem. Commun. 48, 7259–7261 (2012).

Hu, M. et al. Direct Carbonization of Al-Based Porous Coordination Polymer for Synthesis of Nanoporous Carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2864–2867 (2012).

Yang, S. J. et al. MOF-Derived Hierarchically Porous Carbon with Exceptional Porosity and Hydrogen Storage Capacity. Chem. Mater. 24, 464–470 (2012).

Xi, K., Cao, S., Peng, X. Y., Ducati, C., Kumar, R. V. & Cheetham, A. K. Carbon with hierarchical pores from carbonized metal-organic frameworks for lithium sulphur batteries. Chem. Commun. 49, 2192–2194 (2013).

Lim, S. et al. Porous carbon materials with a controllable surface area synthesized from metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Commun. 48, 7447–7449 (2012).

Torad, N. L. et al. Facile synthesis of nanoporous carbons with controlled particle sizes by direct carbonization of monodispersed ZIF-8 crystals. Chem Commun 49, 2521–2523 (2013).

Torad, N. L. et al. Direct Synthesis of MOF-Derived Nanoporous Carbon with Magnetic Co Nanoparticles toward Efficient Water Treatment. Small 10, 2096–2107 (2014).

Aiyappa, H. B., Pachfule, P., Banerjee, R. & Kurungot, S. Porous Carbons from Nonporous MOFs: Influence of Ligand Characteristics on Intrinsic Properties of End Carbon. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 4195–4199 (2013).

Fang, Q. R. et al. Synthesis and crystal structure of a 3D inorganic-organic hybrid compound [Zn3(BTC)2(H2O)3]n with micropores. Chem. J. Chin. Univ.-Chin. 25, 1016–1018 (2004).

Rowsell, J. L. C. & Yaghi, O. M. Effects of functionalization, catenation and variation of the metal oxide and organic linking units on the low-pressure hydrogen adsorption properties of metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 1304–1315 (2006).

Anson, A. et al. Porosity, surface area, surface energy and hydrogen adsorption in nanostructured carbons. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 15820–15826 (2004).

Masika, E. & Mokaya, R. Hydrogen Storage in High Surface Area Carbons with Identical Surface Areas but Different Pore Sizes: Direct Demonstration of the Effects of Pore Size. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 25734–25740 (2012).

Li, Y., Ben, T., Zhang, B., Fu, Y. & Qiu, S. Ultrahigh Gas Storage both at Low and High Pressures in KOH-Activated Carbonized Porous Aromatic Frameworks. Sci Rep 3, 2420 (2013).

Senkovska, I. & Kaskel, S. High pressure methane adsorption in the metal-organic frameworks Cu-3(btc)(2), Zn-2(bdc)(2)dabco and Cr3F(H2O)(2)O(bdc)(3). Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 112, 108–115 (2008).

Makal, T. A., Li, J. R., Lu, W. & Zhou, H. C. Methane storage in advanced porous materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 7761–7779 (2012).

Bae, Y. S. et al. Separation of CO2 from CH4 using mixed-ligand metal-organic frameworks. Langmuir 24, 8592–8598 (2008).

Bastin, L., Barcia, P. S., Hurtado, E. J., Silva, J. A. C., Rodrigues, A. E. & Chen, B. A Microporous Metal-Organic Framework for Separation of CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 by Fixed-Bed Adsorption. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 1575–1581 (2008).

Duan, J. et al. High CO2/CH4 and C2 Hydrocarbons/CH4Selectivity in a Chemically Robust Porous Coordination Polymer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 3525–3530 (2013).

Lu, W. et al. Porous Polymer Networks: Synthesis, Porosity and Applications in Gas Storage/Separation. Chem. Mater. 22, 5964–5972 (2010).

Chen, Z., Xiang, S., Arman, H. D., Li, P., Zhao, D. & Chen, B. Significantly Enhanced CO2/CH4 Separation Selectivity within a 3D Prototype Metal-Organic Framework Functionalized with OH Groups on Pore Surfaces at Room Temperature. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2227–2231 (2011).

Bae, Y. S., Farha, O. K., Spokoyny, A. M., Mirkin, C. A., Hupp, J. T. & Snurr, R. Q. Carborane-based metal-organic frameworks as highly selective sorbents for CO2 over methane. Chem. Commun. 4135–4137 (2008).

Yuan, B., Wu, X., Chen, Y., Huang, J., Luo, H. & Deng, S. Adsorption of CO2, CH4 and N2 on ordered mesoporous carbon: approach for greenhouse gases capture and biogas upgrading. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 5474–5480 (2013).

Himeno, S., Komatsu, T. & Fujita, S. High-pressure adsorption equilibria of methane and carbon dioxide on several activated carbons. J. Chem. Eng. Data 50, 369–376 (2005).

Moellmer, J., Moeller, A., Dreisbach, F., Glaeser, R. & Staudt, R. High pressure adsorption of hydrogen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide and methane on the metal-organic framework HKUST-1. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 138, 140–148 (2011).

Pachfule, P., Biswal, B. P. & Banerjee, R. Control of Porosity by Using Isoreticular Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (IRZIFs) as a Template for Porous Carbon Synthesis. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 11399–11408 (2012).

Liu, Y. H., Xue, J. S., Zheng, T. & Dahn, J. R. Mechanism of lithium insertion in hard carbons prepared by pyrolysis of epoxy resins. Carbon 34, 193–200 (1996).

Srinivas, G., Krungleviciute, V., Guo, Z.-X. & Yildirim, T. Exceptional CO2 capture in a hierarchically porous carbon with simultaneous high surface area and pore volume. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 335 (2014).

Myers, A. L. & Prausnitz, J. M. Thermodynamics of Mixed-Gas Adsorption. AIChE J. 11, 121–121 (1965).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank the financial support of the NSF of China (No. 21271172), the “One Hundred Talent Project” from Chinese Academy of Sciences and the NSF of Fujian Province (No. 2012J01058).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Q.Y. and W.J.W. designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. W.J.W. performed the experiments and prepared the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Yuan, D. Mesoporous carbon originated from non-permanent porous MOFs for gas storage and CO2/CH4 separation. Sci Rep 4, 5711 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05711

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05711

This article is cited by

-

Understanding the ZIF-L to ZIF-8 transformation from fundamentals to fully costed kilogram-scale production

Communications Chemistry (2022)

-

One-pot synthesis of a composite consisting of the enzyme ficin and a zinc(II)-2-methylimidazole metal organic framework with enhanced peroxidase activity for colorimetric detection for glucose

Microchimica Acta (2019)

-

Electrochemiluminescence based detection of microRNA by applying an amplification strategy and Hg(II)-triggered disassembly of a metal organic frameworks functionalized with ruthenium(II)tris(bipyridine)

Microchimica Acta (2018)

-

Recent advances in controlled modification of the size and morphology of metal-organic frameworks

Nano Research (2018)

-

Tunable integration of absorption-membrane-adsorption for efficiently separating low boiling gas mixtures near normal temperature

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.