Abstract

Phylogenetic position of the marine biflagellate Palpitomonas bilix is intriguing, since several ultrastructural characteristics implied its evolutionary connection to Archaeplastida or Hacrobia. The origin and early evolution of these two eukaryotic assemblages have yet to be fully elucidated and P. bilix may be a key lineage in tracing those groups' early evolution. In the present study, we analyzed a ‘phylogenomic’ alignment of 157 genes to clarify the position of P. bilix in eukaryotic phylogeny. In the 157-gene phylogeny, P. bilix was found to be basal to a clade of cryptophytes, goniomonads and kathablepharids, collectively known as Cryptista, which is proposed to be a part of the larger taxonomic assemblage Hacrobia. We here discuss the taxonomic assignment of P. bilix and character evolution in Cryptista.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resolving the phylogenetic relationship amongst major eukaryotic lineages is one of the most challenging subjects in evolutionary biology. In theory, the full diversity of eukaryotes needs to be grasped prior to reconstructing global eukaryotic phylogeny. However, our current knowledge regarding microbial eukaryotes, which comprise the main body of eukaryotic diversity, is insufficient (e.g.1,2). Traditionally, our knowledge of the diversity of microbial eukaryotes has been expanded by isolating and cultivating novel organisms–some of these, like for example Chromera velia3 and Rigifila ramosa4, have been indeed significant for improving our understanding of the origin and evolution of eukaryotes. Once the culture strains are established, we can collect physiological, ultrastructural and molecular data from the cells of interest. However, currently uncultivable microbial eukaryotes are not possible to study in detail by this culture-dependent approach. A recent culture-independent approach, which assesses nucleotide sequence data extracted from eukaryotes in an environmental sample, provides great opportunities for shedding light on the phylogenetically diverse uncultured microbial eukaryotes (e.g.1,2). This approach became one of the standard techniques to survey biodiversity; however, it cannot offer comprehensive knowledge on the individual organism associated with a particular environmental sequence. Practically, neither culture-independent nor culture-dependent approach is dispensable to study biodiversity and organismal phylogeny of eukaryotes. Indeed, the combination of the two approaches successfully established the connection between Picomonas judraskeda and ‘(pico)biliphytes’, which were recognized initially by small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences amplified from the seawater samples5,6.

Palpitomonas bilix is a marine heterotrophic biflagellate with uncertain taxonomic affiliation7; a phylogenetic analysis of six nuclear genes failed to settle the position of P. bilix in global eukaryotic phylogeny. The combination of the morphological and ultrastructural characteristics of P. bilix was novel, albeit some ultrastructural characteristics of this flagellate hinted its possible affinity to the Archaeplasitda or Hacrobia. Archaeplastida is composed of three lineages (i.e., green plants, rhodophytes and glaucophytes); these groups are believed to be the direct descendants of the first plastid-bearing eukaryote8. Nevertheless it remains uncertain how the cyanobacterial endosymbiosis transformed a heterotrophic eukaryote into the common ancestor of Archaeplastida, since no clear phylogenetic affinity has been recovered between Archaeplasitda and any of the extant heterotrophic lineages. If P. bilix is truly related to Archaeplastida, this heterotrophic flagellate likely holds keys to understanding the early evolution of plastids. In contrast to Archaeplastida, Hacrobia is a diverse group comprising both phototrophs (i.e., cryptophytes and haptophytes) and heterotrophs9,10. The plastid genomes of cryptophytes and haptophytes were found to encode a ribosomal protein gene (rpl36) laterally acquired from a bacterium, suggesting that the two photosynthetic lineages were derived from a single photosynthetic ancestor, of which plastid genome encoded the laterally transferred rpl3611. On the other hand, it is widely accepted that cryptophytes possess apparent closer evolutionary affinities to heterotrophic lineages (i.e. goniomonads and kathablepharids), than they are to haptophytes, in the tree of eukaryotes7,12, indicating that cryptophytes and haptophytes are seemingly separated by multiple heterotrophic lineages. Thus, two competing scenarios are possible to explain how cryptophytes and haptophytes share the plastids with the rpl36 of bacterial origin13,14. If the most recent ancestor of cryptophytes and haptophytes (i.e. ancestral hacrobian cell) was phototrophic, all the descendants, except cryptophytes and haptophytes, secondarily lost the original plastid. The alternative scenario, which assumes the ancestral hacrobian cell as heterotrophic, demands two separate plastid acquisitions, one on the branch leading to cryptophytes and the other on the branch leading to haptophytes. Furthermore, a recent phylogenetic study by Burki et al.15 casted doubt on the monophyly of Hacrobia, albeit P. bilix was absent in their analyses. Thus, elucidating the precise position of P. bilix may be significant to further evaluate the validity of Hacrobia monophyly and the plastid evolution of the descendants of the last common ancestor of cryptophytes and/or haptophytes.

We here conducted transcriptomic analyses of P. bilix and the cryptomonad Goniomonas sp. and assembled an alignment composed of 157 genes. Our ‘phylogenomic’ analysis of the 157-gene alignment successfully clarified the phylogenetic position of P. bilix in global eukaryotic phylogeny: P. bilix branched at the base of the assemblage of Cryptophyceae (cryptophytes), Goniomonadea (goniomonads) and Leucocrypta (kathablepharids) that are the members of phylum Cryptista10 with high statistical support. In light of the phylogenetic relationship among P. bilix, cryptophytes, goniomonads and kathablepharids, the character evolution of this monophyletic assemblage is discussed.

Results

Genomic and/or transcriptomic data from 64 eukaryotes were assembled into a 157-gene alignment containing 41,372 unambiguously aligned amino acid positions. Note that we excluded sequence data of uncultivated cells from environmental samples, which were potentially contaminated with distantly related organisms, from this alignment. In the maximum-likelihood (ML) analysis of the 157-gene alignment, we recovered a well-supported clade of stramenopiles, alveolates and rhizarians (SAR16); and one of Tsukubamonas globosa, jakobids, euglenozoans and heteroloboseans (Discoba17), all of which were resolved in pioneering phylogenomic analyses (Fig. 1). Monophyly of neither Excavata nor Hacrobia was positively favored in the ML analyses of the 157-gene alignment, consistent with other phylogenomic studies (e.g.15,18). The tree topology from Bayesian analysis was fundamentally congruent with that from the ML analysis, except for two points: (i) monophyly of Archaeplastida was recovered with a Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) of 1.00 and (ii) the centrohelid Polyplacocystiscontractilis (previously known as Raphidiophrys contractilis) grouped with haptophytes with a BPP of 0.96 (data not shown). As anticipated from phylogenies of small subunit rRNA (SSU rRNA) sequences (e.g.12), our phylogenomic analyses united cryptophytes and Goniomonas sp., with a ML bootstrap percentage value (MLBP) of 100% and a BPP of 1.00 (Fig. 1). The clade of cryptophytes and Goniomonas sp. was then connected to the kathablepharid Roombia truncata with a MLBP of 95% and a BPP of 1.00, which is in good agreement with the results presented in Burki et al.15 and SSU rRNA phylogenies (e.g.12). Finally, P. bilix branched at the base of the clade of crytophytes, Goniomonas sp. and R. truncata with a MLBP of 91% and a BPP of 1.00 (Fig. 1). We additionally conducted the ML analysis including the genomic data amplified from an uncultured picozoan cell19 (Fig. S1). However, the picozoan sequences showed no specific affinity to any members of Cryptista (including P. bilix) or groups/species considered in our dataset (Fig. S1).

Phylogenetic position of Palpitomonas bilix inferred from the maximum-likelihood (ML) analysis of a 157-gene alignment (41,372 amino acid positions).

The 157-protein alignment was analyzed by both maximum-likelihood (ML) and Bayesian methods. As the two methods reconstructed very similar trees, only the ML tree is shown here. Upper and lower values at nodes represent ML bootstrap percentage values (MLBPs) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPPs). MLBPs <60% and BPPs <0.95 are omitted from the figure. Dots correspond to MLBP of 100% and BPP of 1.00.

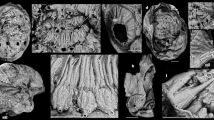

The roll-shaped ejective organelle, i.e., ejectisome (occasionally called as ‘trichocysts’), is identified in cryptomonads, kathablepharids and a few prasinophytes20. Major proteins, which comprise cylindrical coiled ribbons in the ejectisomes of the cryptophyte Pyrenomonas helgolandii, were found to be encoded by tri1, tri2, tri3-1 and tri3-221. We here surveyed tri genes/transcripts in the complete genome of the cryptophyte Guillardia theta and transcriptomic data from the goniomonad Goniomonas sp. and the kathablepharid R. truncata (PRJNA7379315). The Gu. theta genome was found to possess four tri1, eight tri2/3-1 and four tri3-2 genes (Fig. 2: Note that tri2 and tri3-1 are not distinguishable at the amino acid sequence level). We found four tri2/3-1 and three tri3-2 sequences in the transcriptomic data from Goniomonas sp. Two tri2/3-1 and one of tri3-2 sequences were additionally detected from the transcriptome data of another goniomonad species (Goniomonas avonlea; these data were recently generated as a part of the Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project funded by the National Center for Genome Resources and the Gordon and Betty Moor Foundation's Marine Microbiololgy Initiative: http://marinemicroeukaryotes.org/). Likewise, the transcriptomic data from R. truncata contained three tri2/3-1 and two tri3-2 sequences. No tri1 sequence was detected in the data from Goniomonas sp., Go. avonlea or R. truncata even by a sensitive amino acid sequence similarity search using probabilistic methods (HMMER22; data not shown).

Putative protein components of the ejectisomes.

(a). Tri2/3-1 amino acid sequence alignment. Note that Tri2 and Tri3-1 are indistinguishable based on sequence analyses. Amino acid residues shared among more than 15 out of the 19 homologues are shaded. GenBank accession numbers for the amino acid sequences Pyrenomonas helgolandii Tri2 and Tri3-1 are shown in parentheses. For Tri2/3-1 homologues of Guillaria theta, the protein ids are shown parentheses. For those of R. truncate and those of Goniomonas sp. and Go. avonlea, the Genbank accession numbers and contig numbers of their corresponding nucleotide sequences are shown in parentheses, respectively. (b). Tri3-2 amino acid sequence alignment. Amino acid residues shared among more than 9 out of the 11 homologues are shaded. The numbers in parentheses are shown with the same manner as adopted in Figure 2a.

While the 157-gene phylogeny strongly suggests the close affinity of P. bilix to the cryptomonad-kathablepharid clade (Fig. 1), ejectisomes or ejectisome-like structures were not reported from P. bilix7. Consistent with the absence of ejectisomes at the level of ultrastructural observation, we failed to identify any types of tri sequences in the transcriptomic data from P. bilix.

Discussion

We successfully resolved the phylogenetic position of P. bilix by analyzing the 157-gene alignment. This ‘orphan’ flagellate was found to form a robust clade with cryptomonads (i.e., cryptophytes and goniomonads) and the kathablepharid R. truncata. The result presented here supports a taxonomic assignment by Cavalier-Smith10,23, in which P. bilix was placed into subphylum Palpitia under phylum Cryptista. In the 157-gene phylogeny, P. bilix was recovered as the earliest branching lineage amongst cryptists with high statistical support. Cryptomonads have been observed to form a clade with kathablepharids, rather than P. bilix, in phylogenetic analyses of SSU rRNA sequences in which all of P. bilix, cryptomonads and kathablepharids were considered (e.g.7,12). Likewise, the ML analysis of a small-scale multigene alignment united cryptomonads with the kathablepharid Leucocryptos marina, not with P. bilix7. As the relationship among P. bilix, cryptomonads and kathablepharids inferred from the present phylogenomic analyses and SSU rRNA/small-scale multigene phylogenies are consistent with one another, we conclude that cryptomonads are more closely related to kathablepharids than they are to P. bilix within the Cryptista clade.

An earlier study suggested that Picozoa may be related to cryptomonads6. To further examine the possible close relationship between Picozoa and Cryptista including P. bilix, we subjected a phylogenomic alignment including the genomic data, which were generated from a single picozoan cell isolated from seawater19, to the ML analysis. Unfortunately, the additional ML analysis was not able to resolve the precise position of the picozoan sequences in the tree of eukaryotes (Fig. S1), being consistent with the previous phylogenomic studies15. As a large portion (86%) of the picozoan sequences in our phylogenomic alignment is missing, the position of Picozoa needs to be revisited after future genomic and/or transcriptomic analyses on a cultured picozoan strain.

The reliable relationship among P. bilix, cryptomonads and kathablepharids enables us to propose evolutionary scenarios for some morphological and ultrastructural characteristics shared amongst cryptists (see below). Palpitomonas bilix and cryptomonads possess flat mitochondrial cristae7,24,25, while kathablepharids have tubular cristae26. Thus, we propose that flat mitochondrial crista is an ancestral characteristic of cryptists (see ‘LCAC’ in Fig. 3a) and a ‘flat-to-tubular’ transformation of mitochondrial cristae occurred on the branch leading to kathablepharids (marked ‘A’ in Fig. 3a). However, we cannot exclude the alternative possibility, which assumes that the LCAC possessed tubular cristae and ‘tubular-to-flat’ transformation of mitochondrial cristae occurred on the multiple branches in the Cryptista clade.

Character evolution in the Cryptista.

(a). The phylogenetic relationship among cryptophytes, goniomonads, kathablepharids and Palpitomonas bilix, based on the 157-gene phylogeny (see Fig. 1). The putative morphology and ultrastructural characteristics of the last common ancestor of the Cryptista (LCAC) are schematically illustrated. A, Acquisition of the sheath and the conoid-shaped feeding apparatus, loss of bipartite flagellar hairs and ‘flat-to-tubular’ transformation of the mitochondrial cristae; B, Acquisition of the periplast; C, Acquisition of spines and simplification of flagellar hairs; D, Acquisition of ejectisomes. (b). Alternative scenarios of the evolution of lifestyle in Cryptista. Green and orange lines represent phagotrophic and photosynthetic capacities, respectively. left, LCAC employed both phagocytosis and photosynthesis, as anticipated from the chromalveolata hypothesis29; right, LCAC was a non-photosynthetic predator.

The ornamental structures of the cell membrane vary among cryptist members. While P. bilix is a naked cell without any obvious ornamental structures, the cell membrane of cryptomonads is sandwiched by proteinaceous plates called periplasts24 and that of kathablepharids is covered by a sheath structure26. The sheath structure of kathablepharids is composed of structurally distinct two layers27 and seems to be distinct from the periplast of cryptomonads in origin. Consequently, it may be reasonable to consider that they are not homologous structures. We here propose that the ancestral cryptist possessed no ornamental elaboration of the cell membrane (see ‘LCAC’ in Fig. 3a) and the sheath structure and periplast emerged on the branches leading to kathablepharids and cryptomonads, respectively (marked ‘A’ and ‘B’ in Fig. 3a).

Ultrastructurally characterized species of kathablepharids such as Kathablepharis spp. possess a conoid-shaped feeding apparatus, which resembles superficially the apical complex of apicomplexan parasites26. As no conoid-shaped feeding apparatus has been found in any cryptists except kathablepharids, this structure was likely invented on the branch leading to kathablepharids (marked ‘A’ in Fig. 3a) and enabled the flagellates to feed on large-sized prey cells, such as eukaryotic algae (note that goniomonads and P. bilix are bacteriovorus).

Variation in flagellar appendages has been reported among cryptist members. Bipartite flagellar hairs were reported in both P. bilix and cryptophytes7,28. The flagellum of goniomonads has spines and simple flagellar hairs28. The sheath structures that cover the surfaces of kathablepharid cells are further extended to the flagella. Thus, the variation in flagellar accessories found in the Cryptista clade can be reconciled as follows; the ancestral cryptist possessed flagella with bipartite hairs and this feature has been retained in cryptophytes and P. bilix (see ‘LCAC’ in Fig. 3a). It remains unclear whether the ancestral flagella were equipped with a ‘cryptophyte-like’ bilateral row or ‘P. bilix-like’ unilateral row of bipartite hairs. After the divergence of major cryptist lineages, the bipartite flagellar hairs were likely substituted by the spines/simple hairs on the branch leading to goniomonads (marked ‘C’ in Fig. 3a) and replaced by the sheath structures on the branch leading to kathablepharids (marked ‘A’ in Fig. 3a).

Unlike the characteristics discussed above, we can investigate the evolution of the ejectisomes in Cryptista at both ultrastructural and molecular levels. Ejectisomes are found in cryptomonads and kathablepharids20, but not in P. bilix7. As P. bilix, is basal to ejectisome-bearing members of Cryptista, this ejective organelle was most likely established in the common ancestor of cryptomonads and kathablepharids (marked ‘D’ in Fig. 3a). We found tri gene transcripts in the transcriptomic data from all of the ejectisome-bearing cryptist memebers. In contrast, we failed to detect any tri gene transcripts from the transcriptomic data of P. bilix. Curiously, among the four tri genes in cryptophytes (i.e. Py. helgolandii and Gu. theta), the tri1 transcript was missing in both Goniomonas spp. and R. truncata, suggesting that the tri1 gene likely encodes a protein that is unique to cryptophycean ejectisomes. Alternatively, we may have overlooked the tri1 gene sequences in the transcriptomic data from Goniomonas spp. and/or R. truncata, in case of the goniomonad and/or kathablepharid homologues being too diverged from the cryptophyte homologues. To understand the conservation, diversity and evolution of cryptist ejectisomes, the data regarding protein components in both goniomonad and kathablepharid ejectisomes are indispensable.

The chromalveolate hypothesis assumes that cryptophytes, haptophytes, stramenopiles and alveolates derived from a common ancestor bearing a red alga-derived plastid29. As cryptophytes are nested within phagotrophic lineages in the Cryptista clade, this hypothesis demands the ancestral cryptist cell to operate both phagocytosis and photosynthesis (i.e., mixotrophy), followed by changes in lifestyle after the divergence of cryptists—specifically, cryptophytes and other cryptist members would have abandoned phagocytosis and photosynthesis, respectively (Fig. 3b, left). Alternatively, it is also possible that the ancestral cryptist cell was a non-photosynthetic predator and photosynthesis was established after the split of cryptophytes and goniomonads (Fig. 3b, right).

Both morphological/ultrastructural and molecular data from P. bilix are useful to understand character evolution in Cryptista. Nevertheless, we need to re-examine the phylogentic affiliation of Picozoa (see the above discussion) and to survey novel microbial eukaryotes in natural environments, since the true diversity of Cryptista has yet to be uncovered. For instance, environmental PCR surveys have detected two uncultured cryptomonad lineages, CRY-1 and CRY-330,31 and the morphological and molecular data from CRY-1 and CRY-3 are essential to fill the gaps between cryptophytes and goniomonads. We also anticipate that novel cryptist members, which represent lineages branching earlier than P. bilix, remain undetected in nature. Such novel cryptists, if they exist, are significant to understand the early evolution of Cryptista and help resolving the position of Cryptista in the tree of eukaryotes.

Methods

Cultures, RNA extraction and sequencing

Palpitomonas bilix NIES-2562 was maintained in the laboratory at the University of Tsukuba. Goniomonas sp. ATCC PRA-68 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Palpitomonas bilix and Goniomonas sp. were grown in ESM and URO-YT media32, respectively, at 20°C. Approximately 4.19 × 108 cells of P. bilix and 1.31 × 108 cells of Goniomonas sp. were harvested from approximately 15 L of 1-week-old cultures. Total RNA was extracted from the harvested cells using Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsland, CA, USA) by following the manufacturer's protocol. This yielded 0.734 and 0.777 mg of total RNA of P. bilix and Goniomonas sp., respectively. cDNA library constriction and 454 pyro-sequencing by the GS FLX system (454 Sequencing, Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA) were performed at Dragon Genomics Center (TAKARA Bio, Mie, Japan). 104,136 and 132,161 single-path reads from the P. bilix and Goniomonas sp. libraries were assembled into 8,586 and 8,394 contigs, respectively, by the MIRA assembly program version 3.233 with accurate option. The raw sequence data were deposited to GenBank as DRR013022 (P. bilix) and DRR013023 (Goniomonas sp.). The contig sequences are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Phylogenomic analysis

The contig (nucleotide) sequences of P. bilix and Goniomonas sp. were conceptually translated into amino acid sequences by ExPASy translation tool website (http://web.expasy.org/translate) and then added and aligned to the single-protein datasets analyzed in Kamikawa et al.17 manually. We also added the sequence data of R. truncata, Collodictyon triciliatum, Galdieria sulphuraria and Cyanophora paradoxa. Ambiguously aligned positions were excluded from individual alignments manually. Each of the single-protein datasets were subjected to maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis with the LG model34 incorporating empirical amino acid frequencies and among-site rate variation approximated by a discrete gamma distribution with four categories (LG + Γ + F model), in which heuristic tree searches were performed based on 10 randomized maximum-parsimony (MP) starting trees. One hundred bootstrap replicates were generated from each dataset and then subjected to ML bootstrap analysis with the LG + Γ + F model, in which heuristic tree searches were performed from a single MP tree. RAxML ver. 7.6.335 was used for the ML analyses described above. Occasionally, individual protein datasets failed to recover monophylies of Opisthokonta, Amoebozoa, Alveolata, Stramenopiles, Rhizaria, Rhodophyta, Virideplantae, Glaucophyta, Haptophyta, Cryptophyta, Jakobida, Euglenozoa, Heterolobosea, Diplomonadida, Parabasalia, and/or Malawimonadida, because of contamination, erroneous incorporation of paralogues or lateral gene transfers. These cases were detected by searching for splits in individual protein trees that were supported ML bootstrap values ≥70% and that conflicted with the well-accepted taxonomic groups listed above (data not shown). We manually identified the sequences that were responsible for these conflicts and excluded them from the phylogenomic analyses described below. The single-gene alignments were then combined into a phylogenomic (157-gene) alignment. The dataset analyzed in the present study was composed of sequence data from multi-cellular eukaryotes and microbial eukaryotes maintained in the laboratory (see Results for the reason for including no uncultivated organism in the phylogenomic alignment). After preliminary analyses, several rapidly evolving (long-branched) taxa (e.g., Trichomonas and Giardia) were excluded. The final alignment includes 64 taxa with 41,372 amino acid positions. The detailed gap information of each single-gene alignment is supplied in Table S1. The single-gene and 157-gene alignments are available from https://sites.google.com/site/ryomakamikawa/Home/dataset/palpitomonas_2013.

The 157-gene alignment was phylogenetically analyzed by the ML and Bayesian methods using RAxML ver. 7.6.3 and PhyloBayes MPI ver. 1.3b36, respectively. For ML and ML bootstrap analyses, we applied the LG4X model, which allows amino acid equilibrium frequencies and their exchangeabilities to vary across four categories under a distribution-free scheme for site rates37. We evaluated Akaike Information Criterion scores for all of the amino acid substitution models implemented in RAxML and the LG4X model was selected as the most appropriate one to analyze the 157-gene alignment (Table S2). The ML tree was heuristically searched from 10 randomized MP starting trees. In ML bootstrap analyses (100 replicates), heuristic tree search was performed from a single MP tree per replicate. We also subjected the 157-gene alignment to Bayesian analysis with the CAT-Poisson model incorporating among-site rate variation approximated by a discrete gamma distribution. Two Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs were run for 10,000 generations, sampling log-likelihoods every 10 trees. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated after discarding the first 25% of the trees stored during MCMC as ‘burn-in’ (‘maxdiff’ value = 0.24).

Database surveys of tri genes

The putative homologues of tri1, tri2, tri3-1 and tri3-2, which encode the proteins comprising the ejectisomes in the cryptophyte Pyrenomonas helgolandii21, were searched in the transcriptomic data from P. bilix, Goniomonas sp. and R. truncata, as well as in the genome data of the cryptophyte Gu. theta. The nucleotide sequences of tri1, tri2, tri3-1 and tri3-2 of P. helgolandii were used as the queries for tblastx surveys with E-value cut-off <10−10. The deduced amino acid sequences of Tri proteins were manually aligned. tri1 or tri1-like sequences were further surveyed in the transcriptomic data of Goniomonas sp. and R. truncata by HMMER22. The HMM profile was generated from cryptophyte Tri1 amino acid sequences (GenBank accession numbers AFH35045.1, XP_005829861.1, XP_005830134.1, XP_005841702.1 and XP_005824080.1).

References

López-Garcia, P., Philippe, H., Gail, F. & Moreira, D. Autochthonous eukaryotic diversity in hydrothermal sediment and experimental microcolonizers at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 100, 697–702 (2003).

Massana, R., Guillou, L., Díez, B. & Pedrós-Alió, C. Unveiling the organisms behind novel eukaryotic ribosomal DNA sequences from the ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 4554–4558 (2002).

Moore, R. B. et al. A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites. Nature. 451, 959–963 (2008).

Yabuki, A., Ishida, K. & Cavalier-Smith, T. Rigifila ramosa n. gen., n. sp. Filose amoeba with a distinct pellicle, is related to Micronuclearia. Protist. 164, 75–88 (2013).

Seenivasan, R., Sausen, N. Medlin, L. K. & Melkonian, M. Picomonas judraskeda gen. et sp. nov.: the first identified member of the Picozoa phylum nov., a widespread group of picoeukaryotes, formerly known as ‘picobiliphytes’. PLoS ONE. 8, e59565 (2013).

Not, F. et al. Picobiliphytes: a marine picoplanktonic algal group with unknown affinities to other eukaryotes. Science. 315, 253–255 (2007).

Yabuki, A., Inagaki, Y. & Ishida, K. Palpitomonas bilix gen. et sp. nov.: A novel deep-branching heterotroph possibly related to Archaeplastida or Hacrobia. Protist. 161, 523–538 (2010).

Keeling, P. J. The endosymbiotic origin, diversification and fate of plastids. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 365, 729–748 (2010).

Okamoto, N., Chantangsi, C., Horák, A., Leander, B. S. & Keeling, P. J. Molecular phylogeny and description of the novel katablepharid Roombia truncata gen. et sp. nov. and establishment of the Hacrobia taxon nov. PLoS ONE. 4, e7080 (2009).

Cavalier-Smith, T. Symbiogenesis: Mechanisms, evolutionary consequences and systematic implications. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 44, 145–172 (2013).

Rice, D. W. & Palmer, J. D. An exceptional horizontal gene transfer in plastids: gene replacement by a distant bacterial paralog and evidence that haptophyte and cryptophyte plastids are sisters. BMC Biology. 4, 31 (2006).

Ishida, K. et al. Comprehensive SSU rRNA Phylogeny of Eukaryota. Endocyt. Cell Res. 20, 81–88 (2010).

Archibald, J. M. The puzzle of plastid evolution. Curr. Biol. 19, R81–R88 (2009).

Cavalier-Smith, T. Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree. Biol. Lett. 6, 342–345 (2009).

Burki, F., Okamoto, N., Pombert, J. F. & Keeling, P. J. The evolutionary history of haptophytes and cryptophytes: phylogenomic evidence for separate origins. Proc. Biol. Sci. B. 279, 2246–2254 (2012).

Burki, F. et al. Phylogenomic reshuffles the eukaryotic supergroups. PLoS ONE. 2, e790 (2007).

Kamikawa, R. et al. Gene content evolution in discobid mitochondria deduced from the phylogenetic position and complete mitochondrial genome of Tsukubamonas globosa. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 306–315 (2014).

Zhao, S. et al. Collodictyon - an ancient lineage in the tree of eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1557–1568 (2012).

Yoon, H. S. et al. Single-cell genomics reveals organismal interactions in uncultivated marine protists. Science. 332, 714–717 (2011).

Kugrens, P., Lee, R. E. & Corliss, J. O. Ultrastructure, biogenesis and functions of extrusive organelles in selected non-ciliate protists. Protoplasma. 181, 164–190 (1994).

Yamagishi, T., Kai, A. & Kawai, H. Trichocyst ribbons of a cryptomonads are constituted of homologs of R-body proteins produced by the intracellular parasitic bacterium of Paramecium. J. Mol. Evol. 74, 147–157 (2012).

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Computat. Biol. 7, e1002195 (2011).

Cavalier-Smith, T. & Chao, E. E. Oxnerella micra sp. n. (Oxnerellidae fam. n.), a tiny naked centrohelid and the diversity and evolution of heliozoa. Protist. 163, 574–601 (2012).

Kugrens, P. & Lee, R. E. Organization of cryptomonads. The Biology of Free-living Heterotrophic Flagellates. Patterson, D. J. & Larsen, J. (eds.). 219–233 (Clarendon press, Oxford, 1991).

Mignot, J. P. Étude ultrastructurale de (Cyathomonas truncata) from (flagellé Cryptomonadine). J Microsc. (Paris). 4, 239–252 (1965).

Clay, B. & Kugrens, P. Systematics of the enigmatic kathablepharids, including EM characterization of the type species, Kathablepharis phoenikoston and new observations on K. remigera comb. nov. Protist. 150, 43–59 (1999).

Lee, R. E. & Kugrens, P. Katablepharis ovalis, a colorless flagellate with interesting cytological characteristic. J. Phycol. 27, 505–513 (1991).

Kugrens, P., Lee, R. E. & Andersen, R. A. Ultrastructural variations in cryptomonad flagella. J. Phycol. 23, 511–518 (1987).

Cavalier-Smith, T. Principles of protein and lipid targeting in secondary symbiogenesis: Euglenoid, dinoflagellate and sporozoan plastid origins and the eukaryote family tree. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 46, 347–366 (1999).

Shalchian-Tabrizi, K. et al. Diversification of unicellular eukaryotes: cryptomonad colonizations of marine and fresh waters inferred from revised 18S rRNA phylogeny. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 2635–2644 (2008).

Kim, E. & Archibald, J. M. Ultrastructure and molecular phylogeny of the cryptomonad Goniomonas avonlea sp. nov. Protist. 164, 160–182 (2013).

Kasai, F., Kawachi, M., Erata, M., Mori, F., Yumoto, K., Sato, M. & Ishimoto, M. NIES-collection list of strains, 8th edition. Jap. J. Phycol. (Sôrui) 57 (Suppl.), 1–350 (2004).

Chevreux, B. et al. Using the miraEST assembler for reliable and automated mRNA transcript assembly and SNP detection in sequenced ESTs. Genome Res. 14, 1147–1159 (2004).

Le, S. Q. & Gascuel, O. An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1307–1320 (2008).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 22, 2688–2690 (2006).

Lartillot, N., Rodrigue, N., Stubbs, D. & Richer, J. PhyloBayes MPI: Phylogenetic reconstruction with infinite mixtures of profiles in a parallel environment. Syst. Boil. 62, 611–615 (2013).

Le, S. Q., Dang, C. C. & Gascuel, O. Modeling protein evolution with several amino acid replacement matrices depending on site rates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 2921–2936 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Andrew J. Roger (Dalhousie University, Canada) for his technical helps and suggestions. We also thank Dr. Aaron Heiss (University of Tsukuba, Japan) for critical comments and English-language corrections. A.Y., R. K. and S. A. I. were supported by Research Fellowships from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for Young Scientists (Nos. 201242 and 236484 for A.Y., 210528 for R.K. and 24007 for S.A.I.). M.K. was supported by a Discovery grant (227085-2011) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada awarded to Andrew J. Roger. This work was supported by grants from the JSPS awarded to Y.I. (Nos. 21370031, 22657025 and 23117006). Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analyses conducted in the present work have been carried out under the “Interdisciplinary Computational Science Program” in Center for Computational Sciences, University of Tsukuba.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Y., R.K., K.I. and Y.I. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data. M.K., S.A.I., E.K., A.S.T. and K.K. gave technical support and additional data. All authors discussed results and implications. A.Y. and Y.I. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supple. info

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yabuki, A., Kamikawa, R., Ishikawa, S. et al. Palpitomonas bilix represents a basal cryptist lineage: insight into the character evolution in Cryptista. Sci Rep 4, 4641 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04641

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04641

This article is cited by

-

Substrate specificity of plastid phosphate transporters in a non-photosynthetic diatom and its implication in evolution of red alga-derived complex plastids

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Nuclear genome sequence of the plastid-lacking cryptomonad Goniomonas avonlea provides insights into the evolution of secondary plastids

BMC Biology (2018)

-

Comparative mitochondrial genomics of cryptophyte algae: gene shuffling and dynamic mobile genetic elements

BMC Genomics (2018)

-

Extensive molecular tinkering in the evolution of the membrane attachment mode of the Rheb GTPase

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Ophirina amphinema n. gen., n. sp., a New Deeply Branching Discobid with Phylogenetic Affinity to Jakobids

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.