Abstract

In this paper, we study theoretically and experimentally the friction between a rough parabolic or conical profile and a flat elastomer beyond the validity region of Amontons' law. The roughness is assumed to be randomly self-affine with a Hurst exponent H in the range from 0 to 1. We first consider a simple Kelvin body and then generalize the results to media with arbitrary linear rheology. The resulting frictional force as a function of velocity shows the same qualitative behavior as in the case of planar surfaces: it increases monotonically before reaching a plateau. However, the dependencies on normal force, sliding velocity, shear modulus, viscosity, rms roughness, rms surface gradient and the Hurst exponent are different for different macroscopic shapes. We suggest analytical relations describing the coefficient of friction in a wide range of loading conditions and suggest a master curve procedure for the dependence on the normal force. Experimental investigation of friction between a steel ball and a polyurethane rubber for different velocities and normal forces confirms the proposed master curve procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Friction is a phenomenon that people have been interested in for thousands of years but its physical reasons are not clarified completely yet. Not only is it still not possible to predict the frictional force theoretically, there are also no reliable empirical laws of friction which would satisfy the needs of modern technology. In practice, the simplest Amontons' law of dry friction1 is usually used, stating that the force of friction, F, is proportional to the normal force, FN: F = μFN, the proportionality coefficient μ being called coefficient of friction. According to Amontons, the coefficient of friction does not depend on the normal force and the contact area. Amontons did not differentiate between the static and the sliding coefficients of friction, nor even between different materials (he states that the ratio of the frictional force to the normal force is “roughly” one third of the normal force, independently of the contacting materials as long as they are not lubricated1). However, already Coulomb knew that the coefficient of friction, even between the same material pairing, can change by a factor of about four depending on the contact size2 and on the normal force2. As a matter of fact, there are no obvious reasons for the validity of Amontons' law. On the contrary, much effort has been made in the 1940th–60th years to understand why Amontons' law is approximately valid3,4. More recently, the violations of Amontons' “law” became a subject of vivid interest among researchers and focus has shifted towards a detailed understanding of factors responsible for these violations as well as the construction of generalized laws of friction. Several recent studies focused on violations of Amontons' law for static friction due to the dynamics of onset of sliding, which have been studied both experimentally5,6,7 and theoretically in three-dimensional8 and one-dimensional models9,10. These works showed that it is possible to understand and to exactly control the “violations” of the Amontons' law. The detailed dependence of the sliding coefficient of friction on normal force was not studied yet. In the present paper, we investigate the force of sliding friction beyond Amonton's law for elastomers with linear elastic rheology and formulate rules for constructing generalized laws of friction for this class of materials. Theoretical findings are supported by experimental data.

We use the standard assumption that elastomer friction is caused by energy dissipation in the volume of the elastomer due to local deformations11,12. For illustrations and basic understanding we implement this mechanism in the frame of a one-dimensional model based on the method of dimensionality reduction (MDR)13. As this method has recently been subject of a very controversial discussion, we would like to briefly describe the arguments for and against its validity. For small normal or tangential movements of three-dimensional bodies in contact, the total energy dissipation can be calculated either by integrating the dissipation rate density over the whole volume or equivalently determined over total force and displacement. Either method, providing the correct relation between macroscopic forces and displacements is therefore suited for simulation of elastomer friction. It was shown that the force-displacement relation of elastic bodies can be described by a contact with a properly defined one-dimensional foundation, provided the indenter is an (arbitrary) body of revolution13. As the macroscopic contact configuration is one of the essential properties in our treatment, we conclude, that the MDR is appropriate to simulate this “macroscopic part” of the contact problem. Furthermore, the applicability of the method of dimensionality reduction (MDR) (again with respect to the force-displacement relations) was later extended and verified for contacts of randomly rough, self-affine surfaces with elastic14 and viscous15 media and for tangential contacts16. In the paper by Lyashenko et. al.17, the validity of the MDR was questioned. The authors of this paper showed that the MDR does not allow the simulation of the real contact area of random surfaces (apart from the limit of very small forces). This conclusion is correct and is confirmed by Popov in the review paper18 and the monograph16 devoted to the MDR. The force-displacement relations, on the contrary, are correctly described in the frame of the MDR. This was illustrated in16 by comparison with direct three-dimensional simulations of randomly rough surfaces having the spectral power density C(q) ~ q−2H − 2, where q is the wave vector, for values of parameter H in the range −1 < H < 3 as well as for contacts of rough spheres19. This shows, that the MDR can be a useful modeling tool even for simulation of fractal rough surfaces as long as we stay within the standard Grosch' paradigm of the rheological nature of elastomer friction12.

Following the above arguments, we use the MDR as a basis for the simulations of elastomer friction in this paper. As our aim is achieving a basic understanding of frictional behavior between a rigid body and an elastomer, we consider the following simple model: (a) the elastomer is modeled as a Kelvin body, which is completely characterized by its static shear modulus G and viscosity η, (b) the non-disturbed surface of the elastomer is planar and frictionless, (c) the shape of the rigid counter body is assumed to be a superposition of a simple macroscopic profile and random self-affine fractal roughness without long wave cut-off (Figure 1), (d) no adhesion or capillarity effects are taken into account and (e) we consider a one-dimensional model. In the subsequent sections, the restrictions are discussed and the model is generalized for arbitrary linear rheology.

Results

Generalized law of friction for rough indenters with power-law profiles

Let us consider a rigid indenter having the form

consisting of the macroscopic power-shaped profile

and a superimposed roughness h(x), as shown in Figure 1.

Coordinates x and z are measured from the minimum of the macroscopic form, so that g0(0) = 0. The ensemble average of the rough profile is assumed to be zero: 〈h(x)〉 = 0. The roughness was assumed to be a self-affine fractal having the power spectral density C1D ∝ q−2H − 1, where q is the wave vector and H, the Hurst exponent. This one-dimensional power density corresponds to the two-dimensional power density of the form C2D ∝ q−2H −218. The spectral density was defined in the interval from qmin = 2π/L, where L is some reference length, to the upper cut-off wave vector qmax = π/Δx. The spacing Δx determines the upper cut-off wave vector and is an essential physical parameter of the model. Surface topography was characterized by the rms roughness h0, which is dominated by the long wavelength components of the power spectrum and the rms gradient of the surface ∇z, dominated by the short wavelength part of the spectrum. Throughout this paper, we will assume that the indentation depth of the indenter, d, is much larger than the rms value of the roughness,  . This means that the large-scale configuration of the contact is primarily determined by the macroscopic form of the indenter and does not depend on the roughness (Figure 2a).

. This means that the large-scale configuration of the contact is primarily determined by the macroscopic form of the indenter and does not depend on the roughness (Figure 2a).

According to the MDR18, the Kelvin body can be modeled as a series of parallel springs with stiffness Δkz and dash pots with damping constant Δγ (Figure 2b), where

The rigid indenter is pressed into a viscoelastic foundation to the depth d and is moved in tangential direction with velocity v (Figure 1), so that at time t it is described by the equation

For convenience, we introduced the coordinate  in the coordinate system moving together with the rigid indenter.

in the coordinate system moving together with the rigid indenter.

The normal force in each particular element of the viscoelastic foundation is given by

where u is the vertical displacement of the element of the viscoelastic foundation. For elements in contact with the rigid surface, this means that

The normal and the tangential force are determined through equations

We first consider the force of friction at very low velocities. The contact configuration is then approximately equal to the static contact. The uppermost left and uppermost right points −a1 and a2 of the contact (see Figure 2a) are then both determined by the condition g(−a1) − d ≈ g(a2) − d = 0. Because of the relation g(−a1) = g(a2), the integrals  and

and  in (7) and (8) vanish. Therefore

in (7) and (8) vanish. Therefore

We assume that the gradient of the macroscopic shape of the indenter is much smaller than that of the roughness,  , so that

, so that

where ∇z is the rms value of the surface gradient and Lcont = a1 + a2 the contact length. For the coefficient of friction, we get

where τ = η/G is the relaxation time. This equation shows, that both the macroscopic shape of the indenter and the microscopic properties of surface topography determine the coefficient of friction: the contact length is primarily determined by the macroscopic properties (shape of the body and the normal force) while the rms gradient is primarily determined by the roughness at the smallest scale.

Consider the opposite case of high sliding velocities. The detachment of the elastomer from the indenter occurs when the normal force (which is the sum of elastic and viscous force, Eq. (6)) vanishes. If the rms value of the elastic force and the viscous force become of the same order of magnitude, the detachment will occur in almost all points with negative surface gradient, thus a one-sided detachment of the elastomer from the indenter will take place. Characteristic rms values of the three terms in Eq. (6) are proportional to Gd, Gh and ηv∇z. If the indentation depth is much larger than the roughness of the profile,  , then the condition for one-sided detachment of the elastomer from the indenter reads Gd ≈ ηv∇z or

, then the condition for one-sided detachment of the elastomer from the indenter reads Gd ≈ ηv∇z or

In that case, the friction coefficient achieves an approximately constant value20 of

Although this result was derived in ref. 20, we would like to comment here shortly on it. In the plateau region, the elastomer behaves practically as a viscous fluid: the elasticity does not play any role and all contacts are “one-sided.” The normal and tangential forces reduce to  ,

,  . For the normalized coefficient of friction we get

. For the normalized coefficient of friction we get

For an exponential probability distribution function of the gradient of the surface, the ratio of the integrals in (15) is equal to  , in accordance with (14) and it depends only weakly on the form of the distribution function.

, in accordance with (14) and it depends only weakly on the form of the distribution function.

For the macroscopic power law shape (2), the indentation depth and contact radius are given by16

Substituting the contact length Lcont = 2a into equation (12), we obtain the coefficient of friction at low velocities:

where we introduced dimensionless variables

Numerical simulations presented in Figure 3 for the case of a rough cone show that all data in the coordinates  collapse to one master curve with a slope equal to one. The validity of equation (17) was numerically confirmed for the following ranges of parameters. The reference length of the system was L = 0.01 m and the number of elements N = L/Δx was typically 5000. 11 values of the Hurst exponent ranging from 0 to 1 were studied. All values shown below were obtained by averaging over 200 realizations of the rough surface for each set of parameters. Parameter studies have been carried out for 20 different normal forces FN ranging from 10−1 to 101 N, 20 values of the G modulus from 105 to 107 Pa, 20 values of rms roughness h0 from 10−6 to 10−4 m and 20 values of the spacing Δx from 10−7 to 10−5 m, 20 values of angles θ ranging from 5 to 75° and 20 relaxation times τ ranging from 10−4 to 10−2 s, while in each simulation series only one parameter was varied.

collapse to one master curve with a slope equal to one. The validity of equation (17) was numerically confirmed for the following ranges of parameters. The reference length of the system was L = 0.01 m and the number of elements N = L/Δx was typically 5000. 11 values of the Hurst exponent ranging from 0 to 1 were studied. All values shown below were obtained by averaging over 200 realizations of the rough surface for each set of parameters. Parameter studies have been carried out for 20 different normal forces FN ranging from 10−1 to 101 N, 20 values of the G modulus from 105 to 107 Pa, 20 values of rms roughness h0 from 10−6 to 10−4 m and 20 values of the spacing Δx from 10−7 to 10−5 m, 20 values of angles θ ranging from 5 to 75° and 20 relaxation times τ ranging from 10−4 to 10−2 s, while in each simulation series only one parameter was varied.

Dependence of  on ξ at low velocities.

on ξ at low velocities.

Different symbols correspond to different sets of parameters H, v, FN, G, θ, τ and ∇z. All data collapse to one master curve described by equation (17).

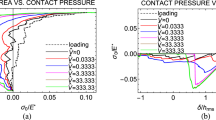

It is easily seen that we can get both limits (12) and (14) by writing

where α is a dimensionless fitting parameter. Numerical simulations (Figure 4) show that this dependence is valid for all parameter sets used in our simulations, while the best fit is achieved with α = 1.5. Interestingly, parameter α seems not to depend on the macroscopic shape of the indenter.

Friction law in a case of a general linear rheology and the “force master curves”

Let us now consider friction of elastomers with a more realistic rheology, which is characterized by the frequency dependent complex shear modulus G(ω) = G′(ω) + iG″(ω), where G′ is the storage modulus and G″ the loss modulus21. At low frequencies, the shear modulus tends towards its static value G0. For simplicity, we will assume that the macroscopic contact mechanics of the indenter is completely governed by the static shear modulus G0, which is correct for sufficiently small sliding velocities. On the other hand, the frictional force is almost completely determined by the smallest wavelength components in the spectrum of roughness and thus by high frequency rheology. The frictional force at low velocities can be therefore estimated by using equation (11) and substituting η → G″(ωmax)/ωmax, where  :

:

The contact length is completely determined by the macroscopic contact mechanics of the indenter, equation (16), where we substitute the constant static shear modulus G0. For the friction coefficient, we therefore get

At high frequencies, the plateau value of  will be achieved. An interpolation between (21) and this value is provided by

will be achieved. An interpolation between (21) and this value is provided by

with α ≈ 1.5. This equation shows that the coefficient of friction for rigid bodies having macroscopic power-law shape has the general form

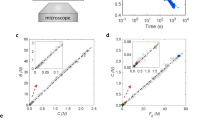

where p(v) is a function of velocity, which depends on the rheological properties of the elastomer. Since FN · p(v) = exp(logFN + logp(v)), this means that the dependencies of the coefficient of friction as a function of logFN will have the same shape for arbitrary velocities, only shifted along the logFN-axis by a velocity-dependent shift factor. This property gives the possibility to construct dependencies of the coefficient of friction on the normal force and the sliding velocity using a “master curve procedure” similar to those used for determining dependencies of the coefficient of friction on velocity from measurements at different temperatures12: Experimental results for the friction coefficient are presented as a function of logFN at various velocities in Figure 5. Following this hypothesis, we assume that at different velocities, the measured curves are only shifted pieces of the same curve. Now, one attempts to shift the curves such that they form a single “master curve” (Figure 6). The resulting curve gives the dependence of the coefficient of friction in a wider range of forces than the range used in the experiment. At the same time, the shift factors at different velocities will provide the dependence of the coefficient of friction on velocity. The result is a complete dependence of the coefficient of friction in a wide range of velocities and forces. Repeated for different temperatures and using the standard master curve procedure12, this will lead to restoring the complete law of friction as function of velocity, temperature and normal force. However, in the present paper, we avoid the well discussed subject of the temperature dependence and concentrate our efforts completely on the force dependence.

Horizontal shifting of the curves shown in Figure 5 relative to the curve at the reference velocity of 1 mm/s provides a “master curve”.

It has two distinct linear parts.

Note that the main logic of the result (23) is not dependent on the details of the model and even on it dimensionality. The scaling relation (23) follows solely from the assumption that the macroscopic form of the contact is determined by the macroscopic properties of material and do not depend on microscopic details and on the other hand, that the microscopic properties are determined mainly by the indentation depth. These general assumptions are equally valid for one-, two- and three dimensional models. Below we explain this important point in more detail.

It is well known, that if a rigid body of an arbitrary shape is pressed against a homogeneous elastic half-space then the resulting contact configuration is only a function of the indentation depth d. At a given indentation depth, the contact configuration does not depend on the elastic properties of the medium and it will be the same even for indentation of a viscous fluid or of any linearly viscoelastic material. This general behavior was recognized by Lee and Radok22,23 and was verified numerically for fractal rough surfaces15. Further, the contact configuration at a given depth remains approximately invariant for media with thin coatings24 or for multi-layered systems, provided the difference of elastic properties of the different layers is not too large25. It was argued that this is equally valid for media which are heterogeneous in the lateral direction (along the contact plane)26. Along with the contact configuration, all contact properties including the real contact area, the contact length, the contact stiffness, as well as the rms value of the surface gradient in the contact area will be unambiguous functions of the indentation depth. The indentation depth is thus a convenient und robust “governing parameter” for contact and frictional properties of media with linear rheology. Note, that this is equally valid for tangential contact. This can easily be illustrated with the example of contact of a rigid body with an incompressible elastic half-space: For a circular contact with an arbitrary radius a, the ratio of the normal stiffness kz and the tangential stiffness kx is constant and given by the Cattaneo-Mindlin factor27,28, for incompressible media kz/kx = 1.5. From this follows that for a frictional contact with the coefficient of friction μ, the maximum tangential displacement to the onset of complete sliding is determined solely by the indentation depth and is equal to ux, max = 1.5 μd. This result does not depend on the form of the body and is valid for arbitrary bodies of revolution29 and even for randomly rough fractal surfaces30. This fact, that the contact configuration is solely determined by the indentation depth is as a matter of fact the only physical reason needed to get the simple scaling relations for the coefficient of friction between rough rigid bodies and linearly viscoelastic elastomers described by equation (23). While the particular form (22) can depend on the model used, the general functional form (23) is a universal one and is not connected with the method of dimensionality reduction used in this paper.

Experimental

Our numerical and theoretical analysis shows that under some conditions the dependencies of the coefficient of friction on the normal force, presented in double logarithmic axes, is self-similar at different velocities and can be mapped onto each other by a simple shifting along the force axis. To prove this hypothesis, we measured the coefficient of friction between a band of polyurethane (PU) and a steel ball with radius R = 50 mm.

The measured coefficients of friction as a function of force are shown in Figure 5. If the shifting procedure formulated in last Section is valid, all the curves shown in this figure have to be considered as different parts of the same curve shifted along the logFN-axis. Figure 6 illustrates that it is indeed possible to shift all the curves to produce one single “master curve”. It is interesting to note that the resulting master curve has two distinct linear regions, meaning a power dependence of the coefficient of friction on the normal force. The crossover between different powers occurs at the force FN ≈ 40 N which coincides with the force  , at which the contact diameter 2a becomes equal to the thickness of the rubber layer D = 10−2 m. At this force the stiffness-force dependence changes from the Hertzian k ∝ F1/3 to k ∝ F1/221 and we expect a change of the scaling relation.

, at which the contact diameter 2a becomes equal to the thickness of the rubber layer D = 10−2 m. At this force the stiffness-force dependence changes from the Hertzian k ∝ F1/3 to k ∝ F1/221 and we expect a change of the scaling relation.

Figure 7 shows the dependence of the shifting factor on the sliding velocity. Roughly speaking, the shifting factor is a linear function of the logarithm of velocity with the slope −0.15. This result can be interpreted as follows. In the intermediate frequency range, the loss modulus G″often is a power function of frequency:

where ω0 is a reference frequency and β a power typically in the range of 0.1 to 0.531. In this case equation (22) can be rewritten as (here for a sphere with radius R, n = 2, cn = 1/R):

In this case, the shift factor is a linear function of logv with the slope −3β/2. Comparing this with the experimental value of −0.15 gives β = 0.1. This is compatible both with the rheological data for the used rubber compound and with data from literature.

Discussion

We analyzed the frictional behavior of elastomers under the following simplifying assumptions: (a) the rigid counter body has a power law shape (e.g. paraboloid or cone), (b) the macroscopic contact mechanics of the indenter is governed mainly by the low frequency shear modulus, which can be assumed to be approximately constant, (c) the friction is governed by the corrugations with the smallest wavelength in the spectrum of the surface roughness. Under these assumptions, we have shown that the coefficient of friction is a function of a dimensionless argument, which is a multiplicative function of powers of velocity and force. The exact form of this argument depends both on the rheology and the macroscopic form of the indenter. But independently of the exact form, the dependence of the coefficient of friction in the range from very small velocities to the plateau occurs to be a universal function of this argument, suggesting a generalization of the known “master curve procedure”: If the dependence of μ on the normal force is presented in double logarithmic coordinates, it will have the same shape for arbitrary velocities, only shifted along the velocity axis. We have proven this procedure with experimental results obtained on polyurethane rubber. In combination with the widely used shifting procedure for varying temperature12, it allows to determine generalized laws of friction as functions of velocity, temperature and normal force. The results of the present paper generalize and validate the results of the pioneering work by Schallamach32.

Methods

MDR calculation

Method of Dimensionality Reduction (MDR) is based on mapping of three-dimensional contact problem to contacts with one-dimensional elastic or viscoelstic foundations18. It gives exact solutions for contacts of bodies of revolution and provides a good approximation for all properties which depend on the force-displacement relationship such as contact stiffness, electrical resistance and thermal conductivity and also dissipated energy and frictional force for elastomers. The details are described in the introduction and at the beginning of the Section Results.

Experiment

The experimental set-up for measuring elastomer friction is shown in Figure 8. The rubber band with a size of 300 × 50 × 5 mm was glued to a moving stage using a solvent-free two-component epoxy glue. We used polyurethan rubber with a static shear modulus of about 3 MPa and yield modulus of 48 MPa. The maximum pressure in the contact area was, in all experiments, at least one order of magnitude smaller than the latter, so that there was no plastic deformation of rubber. The stage could be moved with the aid of a hydraulic actuator with controlled velocity in the range of 5 · 10−4 m/s to 0.58 m/s. The normal and tangential forces were measured with a 3D force sensor, on which the steel ball (radius 25 mm) was mounted. The ambient temperature was 25,5°C (+/− 0,5) and the relative air humidity 30% (+/− 5). Under these conditions the dynamic friction coefficient was measured at constant normal force and horizontal velocity. A total of 1680 measurements were taken. Data for any parameter set (normal force and temperature) was averaged over six measurements. Every measurement series was started at the smallest normal force and increased in steps. At every level of normal force, the measurement was made with 28 horizontal velocities. Before proceeding to the next force level the material was examined for wear both visually and with a microscope and cleaned with pressurized air. At low normal forces wear was virtually non-existent and remained weak even at higher forces. Chemical cleaning agents were not used to treat the surface of the rubber.

Measurements were carried out in the velocity range of 3 · 10−3 m/s to 2 · 10−2 m/s for normal forces in the range of 1 N to 100 N. The lower velocity bound was chosen because the sliding at lower velocities was instationary. The maximum velocity was chosen to avoid significant temperature changes in the contact. The local temperature rise due to frictional heat can be estimated as ΔT ≈ 2μG0dv/λ, where λ ≈ 20 Wm−1K−1 is the thermal conductivity of the steel ball21, which almost completely controls the thermal flow and G0 ≈ 3 · 106 Pa the static shear modulus of the used rubber (Rheological measurements were carried out by Thermoplastics Testing Center of UL International TTC GmbH). For the largest force of FN = 102 N, we get an indentation depth of  . With μ ≈ 0.5 and v = 10−2 m/s we can estimate the average temperature rise as ΔT ≈ 0.06 T. Maximum temperature changes in micro contacts can be estimated as ΔT ≈ 2μG∞h0v/λ, where G∞ ≈ 1.5 · 109 Pa is the glass modulus (Rheological measurements were carried out by Thermoplastics Testing Center of UL International TTC GmbH) of the used rubber and h0 ≈ 10−7 m the rms roughness of the ball, which was determined using a white light interferometric microscope. For velocity v = 10−2 m/s we get an estimation ΔT ≈ 0.08 K which is of the same order of magnitude as the average temperature rise. Due to repeated sliding, the temperature change can get larger than the above estimation. The temperature changes of the rubber surface were controlled in experiments by an infrared camera (see Figure 8). We found empirically that the temperature change does not exceed 1 k for the following range of velocities: up to v ≈ 4 · 10−2 m/s for FN ≈ 102 N, up to v ≈ 2 · 10−2 m/s for FN ≈ 10 N and up to v ≈ 10−2 m/sfor FN ≈ 100 N.

. With μ ≈ 0.5 and v = 10−2 m/s we can estimate the average temperature rise as ΔT ≈ 0.06 T. Maximum temperature changes in micro contacts can be estimated as ΔT ≈ 2μG∞h0v/λ, where G∞ ≈ 1.5 · 109 Pa is the glass modulus (Rheological measurements were carried out by Thermoplastics Testing Center of UL International TTC GmbH) of the used rubber and h0 ≈ 10−7 m the rms roughness of the ball, which was determined using a white light interferometric microscope. For velocity v = 10−2 m/s we get an estimation ΔT ≈ 0.08 K which is of the same order of magnitude as the average temperature rise. Due to repeated sliding, the temperature change can get larger than the above estimation. The temperature changes of the rubber surface were controlled in experiments by an infrared camera (see Figure 8). We found empirically that the temperature change does not exceed 1 k for the following range of velocities: up to v ≈ 4 · 10−2 m/s for FN ≈ 102 N, up to v ≈ 2 · 10−2 m/s for FN ≈ 10 N and up to v ≈ 10−2 m/sfor FN ≈ 100 N.

References

Amontons, G. De la resistance cause'e dans les machines, tant par let frottements des parties qui les component, que par la roideur des cordes qu'on y employe, et la maniere de calculer l'un et l'autre. Mem. l'Academie R. (1699).

Coulomb, C. A. Theorie des machines simple. (Bachelier, 1821).

Bowden, F. P. & Tabor, D. The Friction and Lubrication of Solids. (Clarendon Press, 1986).

Archard, J. F. Elastic Deformation and the Laws of Friction. Proc. R. Soc. London A 243, 190–205 (1957).

Ben-David, O. & Fineberg, J. Static Friction Coefficient Is Not a Material Constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 254301 (2011).

Rubinstein, S. M., Cohen, G. & Fineberg, J. Detachment fronts and the onset of dynamic friction. Nature 430, 1005–1009 (2004).

Ben-David, O., Cohen, G. & Fineberg, J. The Dynamics of the Onset of Frictional Slip. Nature 330, 211–214 (2010).

Otsuki, M. & Matsukawa, H. Systematic Breakdown of Amontons' Law of Friction for an Elastic Object Locally Obeying Amontons' Law. Sci. Rep. 3, 1586; 10.1038/srep01586 (2013).

Capozza, R. & Urbakh, M. Static friction and the dynamics of interfacial rupture. Phys. Rev. B 86, 085430 (2012).

Amundsen, D. S., Scheibert, J., Thøgersen, K., Trømborg, J. & Malthe-Sørenssen, A. 1D Model of Precursors to Frictional Stick-Slip Motion Allowing for Robust Comparison with Experiments. Tribol. Lett. 45, 357–369 (2012).

Greenwood, J. A. & Tabor, D. The Friction of Hard Sliders on Lubricated Rubber: The Importance of Deformation Losses. Proc. Phys. Soc. 71, 989–1001 (1958).

Grosch, K. A. The Relation between the Friction and Visco-Elastic Properties of Rubber. Proc. R. Soc. London A 274, 21–39 (1963).

Heβ, M. On the reduction method of dimensionality: The exact mapping of axisymmetric contact problems with and without adhesion. Phys. Mesomech. 15, 264–269 (2012).

Pohrt, R., Popov, V. L. & Filippov, A. E. Normal contact stiffness of elastic solids with fractal rough surfaces for one- and three-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. E. 86, 026710 (2012).

Kürschner, S. & Popov, V. L. Penetration of self-affine fractal rough rigid bodies into a model elastomer having a linear viscous rheology. Phys. Rev. E. 87, 042802 (2013).

Popov, V. L. & Heβ, M. Methode der Dimensionsreduktion in Kontaktmechanik und Reibung. Eine Berechnungsmethode im Mikro- und Makrobereich. (Springer, 2013).

Lyashenko, I. A., Pastewka, L. & Persson, B. N. J. On the Validity of the Method of Reduction of Dimensionality: Area of Contact, Average Interfacial Separation and Contact Stiffness. Tribol. Lett. 52, 223–229 (2013).

Popov, V. L. Method of reduction of dimensionality in contact and friction mechanics. Friction 1, 41–62 (2013).

Pohrt, R. & Popov, V. L. Contact Mechanics of Rough Spheres: Crossover from Fractal to Hertzian Behavior. Adv. Tribol. 974178 (2013).

Li, Q. et al. Friction between a viscoelastic body and a rigid surface with random self-affine roughness. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 034301 (2013).

Popov, V. L. Contact Mechanics and Friction. Physical Principles and Applications. (Springer, 2010).

Lee, E. H. Stress Analysis in Viscoelastic Bodies. Quart. Appl. Math. 13, 183–190 (1955).

Radok, J. R. M. Viscoelastic stress Analysis. Quart. Appl. Math. 15, 198–202 (1957).

Argatov, I. I. & Sabina, F. J. Spherical indentation of a transversely isotropic elastic half-space reinforced with a thin layer. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 50, 132–143 (2012).

Gao, H. J., Chiu, C. H. & Lee, J. Elastic contact versus indentation modeling of multi-layered materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 29, 2471–2492 (1992).

Popov, V. L. Method of dimensionality reduction in contact mechanics: heterogeneous systems. Phys. Mesomech. 16, 97–104 (2013).

Cattaneo, C. Sul contatto di due corpi elastici: distribuzione locale degli sforzi. Rend. dell Accad. Naz. dei Lincei. 27, 342–348. 434–436, 474–478 (1938).

Mindlin, R. D. Compliance of Elastic Bodies in Contact. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 16, 259–262 (1949).

Ciavarella, M. The generalized Cattaneo partial slip plane contact problem. I—Theory. Int. J. Solids Struct. 35, 2349–2362 (1998).

Grzemba, B., Pohrt, R., Teidelt, E. & Popov, V. L. Maximum micro-slip in Tangential Contact of randomly rough self-affine surfaces. not Publ.

Le Gal, A., Yang, X. & Klüppel, M. Evaluation of sliding friction and contact mechanics of elastomers based on dynamic-mechanical analysis. J. Chem Phys. 123, 014704 (2005).

Schallamach, A. The load dependence of rubber friction. Proc. Phys. Soc. London B 65, 657–661 (1952).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (Germany) under the contract 03EFT9BE55, Q. Li was supported by a scholarship of China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.L.P. and Y.S.C. conceived the research and carried out the analysis, L.V. performed the experiments, Q.L. carried out the numerical simulation, M.P. designed the program code. All authors discussed the results and contributed in preparing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Popov, V., Voll, L., Li, Q. et al. Generalized law of friction between elastomers and differently shaped rough bodies. Sci Rep 4, 3750 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03750

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03750

This article is cited by

-

Investigating frictional contact behavior for soft material robot simulations

Meccanica (2023)

-

Universal limiting shape of worn profile under multiple-mode fretting conditions: theory and experimental evidence

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Friction between a temperature dependent viscoelastic body and a rough surface

Friction (2016)

-

The research works of Coulomb and Amontons and generalized laws of friction

Friction (2015)

-

Comment on “Contact Mechanics for Randomly Rough Surfaces: On the Validity of the Method of Reduction of Dimensionality” by Bo Persson in Tribology Letters

Tribology Letters (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

on ξ for the following set of parameters: FN = 10 N, G = 106 Pa, h0 = 5 · 10−5 m, τ = 10−3 s, H = 0.4 and θ = 10° (conical indenter) or R = 10−2 m (parabolic indenter).

on ξ for the following set of parameters: FN = 10 N, G = 106 Pa, h0 = 5 · 10−5 m, τ = 10−3 s, H = 0.4 and θ = 10° (conical indenter) or R = 10−2 m (parabolic indenter).