Abstract

While DNA methylation plays a role in T-helper (Th) cell maturation, its potential dysregulation in the non-atopic Th1-polarized systemic inflammation observed in obesity-associated asthma is unknown. We studied DNA methylation epigenome-wide in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 8 obese asthmatic pre-adolescent children and compared it to methylation in PBMCs from 8 children with asthma alone, obesity alone and healthy controls. Differentially methylated loci implicated certain biologically relevant molecules and pathways. PBMCs from obese asthmatic children had distinctive DNA methylation patterns, with decreased promoter methylation of CCL5, IL2RA and TBX21, genes encoding proteins linked with Th1 polarization and increased promoter methylation of FCER2, a low-affinity receptor for IgE and of TGFB1, inhibitor of Th cell activation. T-cell signaling and macrophage activation were the two primary pathways that were selectively hypomethylated in obese asthmatics. These findings suggest that dysregulated DNA methylation is associated with non-atopic inflammation observed in pediatric obesity-associated asthma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity and asthma are common and debilitating conditions that are especially prevalent in urban Hispanic and African American populations1,2. Over the past decade, obesity is recognized as an independent risk factor for asthma3,4,5,6,7 and is associated with greater morbidity compared to asthma in normal-weight children8,9. Mechanistic studies suggest that obesity-associated asthma is a distinct entity, but its pathophysiology remains poorly defined10.

While obesity is a chronic inflammatory state characterized by leptin-mediated T helper (Th)1 inflammation11, “classic” childhood asthma is predominantly allergic in nature with a relative bias toward a Th2 phenotype12. In contrast to Th2 inflammation, non-atopic inflammation13,14 with Th1 polarization15 which correlated with lower airway obstruction has been reported in obese asthmatics15, lending support to the hypothesis that obesity-associated asthma is a distinct asthma phenotype.

Both asthma and obesity are multifactorial conditions and likely reflect a combined effect of genetic and environmental modulation16,17. Epigenetic dysregulation manifested by DNA methylation, potentially reflecting the combined genetic and environmental modulation, has been reported in context of both obesity and asthma alone16,17. DNA methylation also plays a role in Th cell differentiation18. However, the potential dysregulation of DNA methylation associated with non-atopic Th-1 polarized systemic inflammation in obesity-associated asthma have not been investigated. To address this gap in knowledge, in a pilot study, we performed an epigenome-wide association study to investigate DNA methylation in Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from obese asthmatic children, comparing it to methylation in PBMCs from children with asthma alone, obesity alone and healthy control individuals. We hypothesized that obese asthmatic PBMCs have distinct epigenome-wide DNA methylation patterns that are associated with Th cell differentiation when compared to the other three study groups. We also proposed to study whether inflammatory pathways activated in the context of obesity-associated asthma are distinct from those activated in normal weight children with asthma and those with obesity alone. Although designed as a pilot study, our results are strongly suggestive of a role for the epigenome in mediating risk associated with obesity in the causation of asthma.

Results

Study population

Demographic characteristics did not significantly differ between the four study groups (Table 1), other than mean weight and BMI z-score, in keeping with the study design. Asthma severity also did not differ between the obese asthmatics and normal-weight asthmatics (p = 0.7). Among obese asthmatics, 12.5% had intermittent, 37.5% had mild persistent, 25% had moderate persistent and 25% had severe persistent asthma while among normal-weight asthmatics, 25% had intermittent, 25% had mild persistent, 25% had moderate persistent and 25% had severe persistent asthma.

Epigenome-wide DNA methylation patterns in obese asthmatics compared to normal weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls

DNA methylation profile in PBMCs from obese asthmatics was distinct from the profile in PBMCs from normal-weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls as seen on volcano plots (Figure 1) and heat maps (Figure 2a). While 7119 loci were differentially methylated in PBMCs from obese asthmatics compared to those from normal-weight asthmatics, 12,875 were differentially methylated compared to PBMCs from obese non-asthmatics and 6773 were differentially methylated when compared to healthy controls (Figure 2b). Two hundred and fifteen loci were consistently differentially methylated in obese asthmatic PBMCs compared to the other three study groups. The top fifty differentially methylated promoter loci with an angle difference of greater than 20 (~20% difference in methylation19) in PBMCs from obese asthmatics compared to those from normal-weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls are summarized in Table 2,3,4.

Volcano plots comparing DNA methylation in obese asthmatics (OA) to (a).

Normal-weight Asthmatics (NwA) (b). Obese non-asthmatics (Ob) and (c). Healthy Controls (HC) (plot of loci specific methylation differences (x-axis) vs. −log10p value (y-axis). The red dots represent the top 1% loci where the methylation difference between the two study groups was greater than 20.

(a). Heat maps of methylation differences discriminating obese asthmatics (OA) from (A) normal weight asthmatics (NwA), (B) obese non-asthmatics (Ob) and (C) healthy controls (HC). Red indicates more methylation and yellow less methylation by HELP-tagging. The columns represent subjects in each study group while the rows are the loci where the methylation difference between the two study groups being compared was greater than 20. (b). Proportional Venn diagram depicting overlap of differentially methylated CpG sites identified when obese asthmatics (OA) were compared to (A) normal-weight asthmatics (NwA), (B) Obese non-asthmatics (Ob) and (C) healthy controls (HC). Two hundred and fifteen loci were consistently differentially methylated in obese asthmatics compared to the other three groups.

Cell to cell signaling and T lymphocyte differentiation were the primary functions of the genes targeted at their promoters for differential methylation that were identified by IPA analysis in PBMCs from obese asthmatics compared to normal-weight asthmatics and healthy controls (Table 5). Compared with normal-weight asthmatics and healthy controls, PBMCs from obese asthmatics had decreased methylation of gene promoters associated with Th cell differentiation (ADAM17, LIF, NHEJ1, AHR, IL2RA, TBX21, and CCL5 (RANTES)). Conversely, gene promoters of FCER2 (CD23), a low affinity receptor for IgE and TGFB1, encoding for TGFβ, secreted by T regulatory cells (Tregs) that controls Th cell differentiation, were hypermethylated in PBMCs from obese asthmatics, compared to normal-weight asthmatics and healthy controls respectively, in keeping with the observed higher Th cell mediated inflammation15,20. Compared to obese non-asthmatics, genes encoding CCL5, PGDR and PI3K, known to influence chemotaxis of natural killer cells and macrophages were hypomethylated and GNA12 and z, members of the G protein family that are ubiquitous in the intracellular signaling pathways were hypermethylated in PBMCs from obese asthmatics.

Differentially methylated pathways in obesity associated asthma

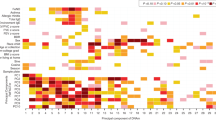

To obtain information about the functional relevance of DNA methylation differences observed at the molecular level, we applied IPA to identify the canonical pathways selected for DNA methylation targeting in PBMCs from obese asthmatics compared to normal-weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls. In keeping with the gene functions identified to be modulated by DNA methylation, the primary canonical pathways found to be differentially methylated in PBMCs from obese asthmatics compared to normal-weight asthmatics including T cell signaling and CCR5 signaling and nitric oxide and reactive oxygen release from macrophages (Figure 3a). As compared to both PBMCs from obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls (Fig. 3b and 3c), obese asthmatics had differential activation of pathways associated with 4-IBB signaling and regulation of activation of IL-2 expression on T lymphocytes. In addition to those discussed above, we retained other pathways in the figure as these pathways appear to be of physiologic significance and it would be interesting if the same pathways were enriched in a larger sample size.

(a). Canonical pathways differentially methylated between obese asthmatics and normal-weight asthmatics. T cell and macrophage signaling and macrophage activation were the primary canonical pathways differentially methylated between obese and normal-weight asthmatics. (b). Canonical pathways differentially methylated between obese asthmatics and obese non-asthmatics. Macrophage activation and T cell signaling were the primary canonical pathways differentially methylated between obese asthmatics and obese non-asthmatics. (c). Canonical pathways differentially methylated between obese asthmatics and healthy controls. Macrophage activation, T cell signaling and IL-15 mediated natural killer (NK) cell modulated Th cell activation were the primary canonical pathways differentially methylated between obese asthmatics and healthy controls.

In addition to canonical pathways, we also mapped the molecular interaction networks utilizing IPA software. In the network comparing obese asthmatics to normal-weight asthmatics, we found that while the IFNγ promoter itself was not differentially methylated, it was the hub of the enriched pathways and was associated with other differentially methylated factors (Figure 4a). Further, while factors associated with known obesity-specific innate immune mechanisms (including ALOX15, IGFB4, SOCS2 and SOCS3) were hypomethylated in obese non-asthmatics, obese asthmatics had evidence of hypomethylation of IFNG, CCL5 and PPARG promoters, cytokines and transcription factors associated with both innate and non-atopic adaptive immunity (Figure 4b). Similarly, as compared to healthy controls, promoters of CCL5 and CSF1 gene, associated with macrophage mediated inflammation and differentiation and survival respectively, was hypomethylated in PBMCs from obese asthmatics (Figure 4c).

(a). Network of differentially methylated molecules in obese asthmatics compared to normal-weight asthmatics. Genes encoding for molecules in red nodes are hypomethylated in obese asthmatics while those in green nodes are hypermethylated relative to normal weight asthmatics. (b). Network of differentially methylated molecules in obese asthmatics compared to obese non-asthmatics. Genes encoding for molecules in red are hypomethylated in obese asthmatics while those in green are hypermethylated relative to obese non-asthmatics. The nodal relationships indicated in solid lines denote direct while those in dashed lines denote indirect interactions. The shape of each node denotes the molecule class: horizontal ovals are transcription factors, vertical ovals are transmembrane receptors, horizontal diamonds are peptidases, vertical diamonds are enzymes, squares are growth factors, horizontal rectangles are nuclear receptors, vertical rectangles are ion channels, inverted triangles are kinases and circles are “other” molecules. (c). Network of differentially methylated molecules in obese asthmatics compared to healthy controls. Genes encoding for molecules in red are hypomethylated in obese asthmatics while those in green are hypermethylated relative to healthy controls. The nodal relationships indicated in solid lines denote direct while those in dashed lines denote indirect interactions. The shape of each node denotes the molecule class: horizontal ovals are transcription factors, vertical ovals are transmembrane receptors, horizontal diamonds are peptidases, vertical diamonds are enzymes, squares are growth factors, horizontal rectangles are nuclear receptors, vertical rectangles are ion channels, inverted triangles are kinases and circles are “other” molecules.

Discussion

In this pilot study, we found evidence to support the hypothesis that PBMCs derived from pre-adolescent obese asthmatic minority children have distinct patterns of DNA methylation differing from those observed in PBMCs from normal weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls. There was decreased promoter methylation of a subset of genes that encode for molecules associated with innate immune and non-atopic patterns of inflammation, including CCL521, IL2RA22 and TBX2123, a transcription factor associated with increased Th1 differentiation, while promoter methylation of FCER (CD23), a low affinity receptor for IgE24 and of TGFB1, released by Tregs to control T cell mediated inflammation25, was increased. Together, differential methylated molecules in PBMCs from obese asthmatic children were associated with pathways linked to T cell differentiation and increased macrophage activation, the two primary cell types that have been linked to the pathophysiology of obesity-associated asthma20,26. We have previously demonstrated that obesity-associated asthma is associated with Th1 polarization in this study sample, with increased Th1/Th2 cell ratio when compared to normal-weight asthmatics15, providing a biological pathway for prior reports of non-atopic pattern of inflammation in obesity-associated asthma13,27. Epigenome wide methylation patterns found in the current study suggest that DNA methylation may play a role in the observed Th1 polarization among obese asthmatics.

We utilized an epigenome-wide methylation assay that yielded quantitative DNA methylation data on ~2.0 million loci. Previous studies performed in our laboratory using this technology have reported a strong correlation between genome-wide and single locus methylation19,28,29, supporting the inferences drawn from the epigenome-wide studies. Our approach is different from those previously utilized in epigenetic studies done in context of asthma where single gene promoter methylation sites were studied among asthmatics using bisulphite MassArray or Pyrosequencing30. In addition to obtaining promoter-specific methylation data by our approach, we were able to obtain methylation profiles on other genes not routinely studied in the context of obesity or asthma. These methylation profiles were used to elucidate the interaction between the products of the differentially methylated genes, thereby identifying pathways that are modulated by DNA methylation and play a role in the inflammatory patterns observed among obese asthmatics. This information provides a more comprehensive insight into the complex interactions between inflammatory pathways activated by the co-existence of two chronic inflammatory conditions, asthma and obesity.

In keeping with the atopic phenotype of asthma among normal weight individuals, prior studies of DNA methylation profiles performed in asthmatics have found decreased methylation of IL-4 promoter and increased methylation of IFNγ promoter in adults30 and children31, confirming the role of methylation in naïve Th cell maturation32 and in asthma. Differential methylation has correlated with cytokine production by the cells providing evidence of the functional implications of methylation30,31. Recently, using massively-parallel sequencing, Kim et.al. have demonstrated differential methylation in bronchial mucosa from atopic adults with asthma compared to non-atopic asthmatics, providing additional support for the role of DNA methylation in asthma pathogenesis33. Consistent with our findings of Th1 polarization with lower serum levels of IL-13 and higher levels of IL-6 and TNFα, as well as higher Th1/Th2 cell ratio in obese asthmatic pre-adolescent children15, we found hypomethylation of CCL5, a pro Th1 chemokine21 that has strong chemotaxis not only for naïve and memory T cells but also for macrophages, the primary cell associated with obesity mediated inflammation34. Similarly, TBX21, a transcription factor involved in selective differentiation of naïve Th cells into Th1 cells23 was also hypomethylated in PBMCs from obese asthmatics relative to healthy controls. However, since similar differences in TBX21 methylation were not observed between obese and normal-weight asthmatics, it is possible that differential methylation of other pathways, such as those mediated by GATA3, a Th2 transcription factor or downstream molecules such as IL-4, IL-5 or IL-13, may also play a role in the observed Th1 polarization among obese asthmatics relative to normal-weight asthmatics. Conversely, there was evidence of hypermethylation of IgE receptor CD2324 in obese asthmatics compared to normal-weight asthmatics. CD23 is proposed to play a role in antigen presentation and regulation of immune responses, particularly with enhancement of IgE mediated T and B cell responses24. Together these results provide evidence that observed patterns of DNA methylation likely play a role in non-atopic inflammatory phenotype of obesity-associated asthma.

Stefanowicz et al.35 recently demonstrated cell-specific methylation differences in context of asthma and atopy, a systemic disease, highlighting the need for simultaneous investigation of DNA methylation in cells obtained from systemic circulation and from disease-targeted organs. They, however, did not find any significant methylation differences in PBMCs obtained from asthmatics and healthy controls, findings that differ from our observations. There may be several factors contributing to the observed differences. There were inherent differences in the technique used to elucidate methylation patterns. While our method using DNA methylation specific restriction enzymes followed by ligation mediated PCR amplification allows the study of ~2 million loci, Stefanowicz et al. investigated methylation at 1505 loci on bisulphite treated DNA using a cancer panel, potentially limiting their ability to identify differential methylation at several additional loci. Moreover, our study cohort included older children, so inherent differences in age, as well as potential differences in ethnicity and asthma severity between the two study samples may offer additional explanations for the differences. Prior studies investigating the influence of ethnicity on clinical phenotypes have identified ethnicity-specific single nucleotide polymorphisms that correlate with clinical parameters including peripheral white cell counts36 and disease such as multiple sclerosis37. Whether similar ethnicity-specific differences in the epigenome are associated with disease incidence and severity needs further investigation.

Macrophages are the primary cell type linked to obesity-mediated inflammation34. Recent studies have demonstrated that alveolar macrophages in adult obese asthmatics are of the pro-inflammatory phenotype that can be activated by leptin alone26. We found that PBMCs from obese non-asthmatics had evidence of decreased promoter methylation of several proteins including ALOX15, IGFBP4, SOCS2 and SOCS3 that are associated with obesity-specific activation of innate immune pathways38. However, in PBMCs from obese asthmatics, key cytokines and inflammatory mediators released by macrophages and involved in monocyte chemotaxis and proliferation and survival including CCL5 and CSF1, and downstream molecules such as PI3K involved in T cell differentiation39, signal transduction and NFκB pathway40 were hypomethylated compared to obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls, together supporting a greater role of macrophage-mediated inflammation in childhood obesity-associated asthma, relative to children with obesity alone and healthy controls. Given that obesity-mediated inflammation is primarily driven by leptin11 and leptin levels in our cohort were higher among obese asthmatics than obese non-asthmatics15, we speculate that DNA methylation may be one mechanism by which leptin may be influencing macrophage function and systemic inflammation among obese asthmatics. In keeping with the complex biological pathways influenced by methylation, while systemic Th1 polarization was observed in obese asthmatic children15, IFNγ promoter itself was not differentially methylated in obese asthmatics compared to normal-weight asthmatics. We observed that other differentially methylated molecules indirectly related with IFNγ promoter and maybe altered the IFNγ pathway but the extent to which these potentially played a role in the Th1 polarization by modulating IFNγ production needs further investigation.

This study has a small sample size and only represents a first attempt to determine whether epigenetic changes are involved in obesity-associated asthma, with limited power to detect anything but the strongest and most consistent changes. Furthermore, we recognize that our use of mixed PBMCs, comprised of T cells, B cells and monocytes, reduces our ability to detect T cell-specific changes. To have generated data indicative of systematic changes occurring at loci with properties consistent with a role in asthma and obesity indicates that this avenue is worth pursuing further and that epigenome-wide DNA methylation analysis can identify additional genes which may orchestrate the observed inflammatory patterns needs additional investigation. These results suggest that DNA methylation influences several genes that together determine the phenotype associated with a particular disease. As recently highlighted41, identification of a pathway in addition to methylation differences at a single gene level is needed to better define the pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with pulmonary disease and identify key biomarkers that may be amenable to pharmacologic intervention, given the reversible nature of DNA methylation42. We also recognize the lack of gene expression studies, due to limited number of PBMCs, limits the extrapolation of our results into biological consequences. However, since we had previously observed a Th1 polarized phenotype in the same samples that underwent quantification of DNA methylation, our current results provide a foundation for potential role of DNA methylation in Th1 polarization in obese asthmatics and provide pilot data for future studies to validate our findings with gene expression studies. Given our small sample size, our results are also susceptible to by-chance findings. Hence, future studies of DNA methylation patterns of individual cell types combined with gene expression studies within the peripheral blood mononuclear cells are needed to better determine the role of methylation in the differentiation and activation of each immune cell in obese asthmatics.

In conclusion, in a pilot study investigating DNA methylation patterns among obese asthmatic pre-adolescent children compared to those with asthma alone, obesity alone and healthy controls, we found that methylation patterns in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in obesity-associated asthma are distinct and are indicative of activation of innate and adaptive immune responses, including T cell differentiation and release of pro-inflammatory substances from macrophages. Although both obesity and obesity-associated asthma have similar inflammatory profiles with systemic non-atopic inflammation, the DNA methylation patterns suggest inherent differences with activation of distinct inflammatory pathways in obese asthmatics. Further studies are needed to investigate which cell types are contributing to the observed methylation patterns and to confirm and validate our findings.

Methods

Study material and ethics statement

Peripheral blood samples used to study genome-wide methylation were a subgroup of samples obtained from pre-adolescent minority children participating in a study investigating inflammatory patterns in obesity-associated asthma15. This subgroup consisted of samples from 32 children, including 8 from each of the 4 study groups of obese asthmatics, normal-weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls where the parent/legal guardian of the participating child had given written informed consent for use of the residual PBMCs for future studies. As previously described, obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 95th percentile for age and normal-weight as BMI less than the 85th percentile15. Asthmatics were those diagnosed by their primary care physicians, as per the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines43. Co-existence of atopic conditions including allergic rhinitis and eczema did not differ between the two study groups with asthma. The characteristics of the subgroup including demographics and asthma severity did not differ from those of the parent study. The Institutional Review Board at Montefiore Medical Center approved the parent study as well as the use of residual de-identified samples for the current study.

The Ficoll-Hypaque method was used to isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from whole blood, the purity of which was confirmed by flow cytometry [Figure S1]. The cells were aliquoted, frozen in 10% DMSO and stored in liquid nitrogen until further processing. Genomic DNA was isolated from aliquots of 3 × 106 PBMCs using Gentra Puregene Blood kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

HELP-tagging assay to test DNA methylation

Epigenome-wide methylation studies in PBMCs from the four study groups were performed by using the massively-parallel sequencing (MPS)-based HELP-tagging assay on the genomic DNA as previously reported44,45. Briefly, 5 μg of genomic DNA was digested by HpaII and purified by phenol/chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. The digested DNA was then ligated at the cohesive end to the first adaptor including a restriction enzyme site that was digested by EcoP151 followed by ligation of the second adaptor that was MPS compatible. These adaptors served as priming sites for ligation-mediated PCR amplification. Further, to generate longer flanking sequences, a T7 polymerase was added followed by a reverse transcription step, allowing the generation of libraries for MPS that were compared to human MspI reference libraries. Libraries were sequenced using Illumina Genome GAIIx/HiSeq 2000 sequencer following the manufacturer's instructions.

While MspI digestion is methylation insensitive and cuts the DNA at all CCGG sites, HpaII digestion is methylation sensitive and cuts DNA only at CCGG sites where the central CG is unmethylated at the cytosine nucleotide. Comparison of HpaII count to MspI count for each locus thereby allows quantification of methylation. The angle obtained by plotting HpaII count on the y-axis and MspI count on the x-axis provides a quantitative measure of locus-specific methylation. A higher angle formed when HpaII count is high relative to MspI is evidence of relative hypomethylation while a smaller angle is evidence of hypermethylation19. Prior studies in our lab have demonstrated a correlation of ~0.9 between replicates and between angle values obtained by HELP-tagging and quantification of methylation by bisulphite MassArray (Sequenom)19,28,29.

Library quality assessment

As described by Jing et al.45, the Illumina genome analyzer uses the CASAVA software to perform image analysis and base calling, the outputs from which are the raw sequence reads in Illumina's QSEQ format. For quality assessment of the sequences, each noncallable (unknown) base represented as a period is converted to “N”, which are statistically analyzed to assess sequencing success and individual cycle efficacy. The library quality is further assessed by determining the proportion and position of the 3′ adaptor sequence within the reads, where the first two CG represent the cohesive end for ligation of HpaII digestion products and the other six nucleotides are the EcoP151 recognition site. A high percent of reads containing the adaptor sequence starting at position 27 is indicative of a high quality library. By removing sequences with excessive tracts of unknown bases (“N”s) and those lacking the adaptor sequence, spurious sequences are eliminated. Of the remaining sequences, the first base is removed since it originated from the 3′ adaptor ligation and the 5′ adaptor is masked by replacing the bases with “N”s to maintain a uniform tag size. Illumina's alignment algorithm, ELAND, treats unknown (“N”) bases as wild cards and therefore does not penalize them during alignment to the reference genome. During the alignment, a maximum of two mismatches are allowed and insertion/deletions are ignored. Statistics generated from the alignment include details on rejection of sequences that had greater than 10 aligned hits and those with no match at all, retaining only those that had unique or fewer than 10 aligned hits that were mapped to an annotated HpaII site. The counts of sequence tags aligned adjacent to every HpaII/MspI site are assessed. Tags that align to more than one locus are given a proportional count. Cumulative HpaII counts are normalized with MspI counts for each HpaII/MspI annotated site. To quantify methylation, the normalized accumulative proportional (NAP) count for the HpaII digested sample and the MspI reference sample are represented as Cartesian coordinates for vectors projected in two dimensional space where the Y axis represents the HpaII NAP count and the X-axis represents the MspI NAP count. Represented as a vector, the direction (angle relative to the origin) corresponds to quantification of hypomethylation. These angle values are then linear scaled to a range from 0 to 100 and stored as WIG files45. On an average, methylation status of 1.8 × 106 loci is obtained per sample.

Data snalysis

Demographic characteristics of the study population were analyzed using STATA statistical software version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). DNA methylation results were analyzed using R (version 2.12.0 (http://www.R-project.org). The MPS output was pre-processed and underwent normalization for total count numbers as described above. The locus-specific angle obtained by plotting HpaII against MspI was compared between obese asthmatics and normal weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls, using paired T-test. The small sample size in this pilot study does not allow us to set a False Discovery Rate, or adjust for multiple testing. We therefore analyzed the biological significance of the top 2 × 104 or the top 1% most consistently differentially methylated loci in obese asthmatics compared to normal-weight asthmatics, obese non-asthmatics and healthy controls in which differential methylation were defined as an absolute difference of angle value of >20, corresponding to ~20% difference in methylation. We report the locus-specific differential methylation in obese asthmatics compared to the other three study groups. Differentially methylated loci were defined in terms of genomic context (e.g., occurring in a gene promoter, defined as ± 1000 base pairs from the transcription start site). All p values reported are two tailed with statistical significance set a priori at 0.05. All data are available through the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GEO:GSE43705).

Ingenuity pathway analysis

The biologic function application of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA, www.ingenuity.com, Redwood City, CA) was used to investigate whether differentially methylated gene promoters were enriched for specific functional relationships. The analysis was filtered to human genes and to immune cells. Canonical pathway identification was filtered to those associated with cellular or humoral immune response, or cytokine signaling. Differentially methylated gene promoters in obese asthmatic PBMCs associated most strongly with functional networks relevant to cell to cell signaling when compared to normal weight asthmatics, chemotaxis of natural killer (NK) cells when compared to obese non-asthmatic and differentiation of T lymphocytes when compared to healthy control PBMCs. Graphic representation of the canonical pathways and the functional networks was obtained from IPA.

References

New York State Asthma Surveillance Summary Report, October 2009. http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/ny_asthma/pdf/2009_asthma_surveillance_summary_report.pdf.

Matte, T. Ellis, J. A. Bedell, J. Selenic, D. Young, C. & Deitcher, D. Obesity in the South Bronx: A look across generations, New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene,. 2007. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/dpho/dpho-bronx-obesity.pdf.

Lang, J. E., Feng, H. & Lima, J. J. Body Mass Index-Percentile and Diagnostic Accuracy of Childhood Asthma. Journal of Asthma 46, 291–299, 10.1080/02770900802712963 (2009).

Bibi, H. et al. The relationship between asthma and obesity in children: is it real or a case of over diagnosis? J Asthma 41, 403–410 (2004).

Cassol, V. E. et al. Obesity and its relationship with asthma prevalence and severity in adolescents from southern Brazil. J Asthma 43, 57–60, T42P625L8J650U07 [pii]10.1080/02770900500448597 (2006).

Figueroa-Munoz, J. I., Chinn, S. & Rona, R. J. Association between obesity and asthma in 4–11 year old children in the UK. Thorax 56, 133–137 (2001).

Sithole, F., Douwes, J., Burstyn, I. & Veugelers, P. Body mass index and childhood asthma: a linear association? J Asthma 45, 473–477, 794833837 [pii]10.1080/02770900802069117 [doi] (2008).

Ginde, A. A., Santillan, A. A., Clark, S. & Camargo Jr, C. A. Body mass index and acute asthma severity among children presenting to the emergency department. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 21, 480–488, PAI911 [pii]10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00911.x [doi] (2010).

Belamarich, P. F. et al. Do obese inner-city children with asthma have more symptoms than nonobese children with asthma? Pediatrics 106, 1436–1441 (2000).

Dixon, A. E. et al. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop report: obesity and asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc 7, 325–335 (2010).

Ferrante, A. W., Jr Obesity-induced inflammation: a metabolic dialogue in the language of inflammation. J Intern Med 262, 408–414 (2007).

Cho, S. H., Stanciu, L. A., Holgate, S. T. & Johnston, S. L. Increased Interleukin-4, Interleukin-5 and Interferon γ in airway CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171, 224–230 (2005).

Nagel, G. et al. Associations of adipokines with asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in German schoolchildren. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 20, 81–88, 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00740.x (2009).

Mai, X. M., Chen, Y. & Krewski, D. Does leptin play a role in obesity-asthma relationship? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 20, 207–212 (2009).

Rastogi, D. et al. Obesity-associated asthma in children: A distinct entity. CHEST 141, 895–905 (2012).

Sharma, S. et al. The impact of self-identified race on epidemiologic studies of gene expression. Genet Epidemiol 35, 93–101 (2011).

Gluckman, P. D. & Hanson, M. A. Developmental and epigenetic pathways to obesity: an evolutionary- developmental perspective. Int J Obes 32, S62–71 (2008).

Agarwal, S. & Rao, A. Modulation of chromatin structure regulates cytokine gene expression during T cell differentiation. Immunity 9, 765–775 (1998).

Suzuki, M. & Greally, J. M. DNA methylation profiling using HpaII tiny fragment enrichment by ligation-mediated PCR (HELP). Methods 52, 218–222, 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.04.013 (2010).

Dixon, A. E. et al. Relationship of adipokines with immune response and lung function in obese asthmatic and non-asthmatic women. J Asthma 48, 811–817 (2011).

Lapteva, N. & Huang, X. F. CCL5 as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 10, 725–733 (2010).

Liao, W., Lin, J. X. & Leonard, W. J. Interleukin-2 at the crossroads of effector responses, tolerance and immunotherapy. Immunity 38, 13–25 (2013).

Miller, S. A. & Weinmann, A. S. Molecular mechanisms by which T-bet regulates T-helper cell commitment. Immunol Rev 238, 233–246 (2010).

Acharya, M. et al. CD23/FcεRII: molecular multi-tasking. Clin Exp Immunol 162, 12–23 (2010).

Vignali, D. A. A., Collison, L. W. & Workman, C. J. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Immunol 8, 523–532 (2008).

Lugogo, N. L. et al. Alveolar macrophages from overweight/obese subjects with asthma demonstrate a proinflammatory phenotype. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 186, 404–411 (2012).

von Mutius, E., Schwartz, J., Neas, L. M., Dockery, D. & Weiss, S. T. Relation of body mass index to asthma and atopy in children: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study III. Thorax. 56, 835–838 (2001).

Pascual, M. et al. Epigenetic changes in B lymphocytes associated with house dust mite allergic asthma. Epigenetics 6, 1131–1137 (2011).

Einstein, F. et al. Cytosine methylation dysregulation in neonates following intrauterine growth restriction. PloS One 5, e8887 (2010).

Kwon, N. H., Kim, J. S., Lee, J. Y., Oh, M. J. & Choi, D. C. DNA methylation and the expression of IL-4 and IFN-gamma promoter genes in patients with bronchial asthma. J Clin Immunol 28, 139–146, 10.1007/s10875-007-9148-1 (2008).

White, G. P. et al. CpG methylation patterns in the IFNgamma promoter in naive T cells: variations during Th1 and Th2 differentiation and between atopics and non-atopics. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 17, 557–564, 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00465.x (2006).

Miller, R. L. & Ho, S. M. Environmental epigenetics and asthma: current concepts and call for studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 177, 567–573 (2008).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling of the bronchial mucosa of asthmatics: relationship with atopy. BMC Med Genet 14 (2013).

Dalmas, E., Clément, K. & Guerre-Millo, M. Defining macrophage phenotype and function in adipose tissue. Trends Immunol 32, 307–314 (2011).

Stefanowicz, D. et al. DNA methylation profiles of airway epithelial cells and PBMCs from healthy, atopic and asthmatic children. PloS One 7, e44213 (2012).

Nalls, M. A. et al. Admixture mapping of white cell count: genetic locus responsible for lower white blood cell count in the Health ABC and Jackson Heart studies. Am J Hum Genet 82, 81–87 (2008).

Patterson, N. et al. Methods for high-density admixture mapping of disease genes. Am J Hum Genet 74, 979–1000 (2004).

Campión, J. M. F. & Martínez, J. A. Individuality and epigenetics in obesity. Obes Rev 10, 383–392 (2009).

Han, J. M., Patterson, S. J. & Levings, M. K. The Role of the PI3K Signaling Pathway in CD4(+) T Cell Differentiation and Function. Front Immunol 3 (2013).

Sanchez-Margalet, V. & Martin-Romero, C. Human leptin signaling in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: activation of the JAK-STAT pathway. Cell Immunol 211, 30–36 (2001).

Center, D. M. et al. Genomic Medicine and Lung Diseases: NHLBI Workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186, 280–285 (2012).

How Kit, A., Nielsen, H. M. & Tost, J. DNA methylation based biomarkers: Practical considerations and applications. Biochimie (2012).

Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Institute of Health: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, 2007. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/.

Suzuki, M. et al. Optimized design and data analysis of tag-based cytosine methylation assays. Genome Biol 11, R36, 10.1186/gb-2010-11-4-r36 (2010).

Jing, Q., McLellan, A., Greally, J. M. & Suzuki, M. Automated computational analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiling data from HELP-tagging assays. Methods Mol Biol 815, 79–87 (2012).

Scheller, J., Chalaris, A., Garbers, C. & Rose-John, S. ADAM17: a molecular switch to control inflammation and tissue regeneration. Trends Immunol 32, 380–387 (2011).

Pot, C., Apetoh, L., Awasthi, A. & Kuchroo, V. K. Molecular pathways in the induction of interleukin-27-driven regulatory type 1cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res 30, 381–388 (2010).

Mathieu, M. E. et al. LIF-dependent signaling: new pieces in the Lego. Stem Cell Rev 8, 1–15 (2012).

Sekiguchi, J. M. & Ferguson, D. O. DNA double-strand break repair: a relentless hunt uncovers new prey. Cell 124, 260–262 (2006).

Barouki, R., Aggerbeck, M., Aggerbeck, L. & Coumoul, X. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor system. Drug Metabol Drug Interact 27, 3–8 (2012).

Hall, J. A. & Georgel, P. T. CHD proteins: a diverse family with strong ties. Biochem Cell Biol 85, 463–476 (2007).

Croft, M. et al. TNF superfamily in inflammatory disease: translating basic insights. Trends Immunol 33, 144–152 (2012).

Oguma, T., Asano, K. & Ishizaka, A. Role of prostaglandin D(2) and its receptors in the pathophysiology of asthma. Allergol Int 57, 307–312 (2008).

Cabrera-Vera, T. M. et al. Insights into G protein structure, function and regulation. Endocr Rev 24, 765–781 (2003).

Gough, D. J., Levy, D. E., Johnstone, R. W. & Clarke, C. J. IFNgamma signaling-does it mean JAK-STAT? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 19, 115–124 (2008).

Guzman-Rojas, L. et al. PRELI, the human homologue of the avian px19, is expressed by germinal center B lymphocytes. Int Immunol 12, 607–612 (2000).

Mouchemore, K. A. & Pixley, F. J. CSF-1 signaling in macrophages: pleiotrophy through phosphotyrosine-based signaling pathways. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 49, 49–61 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The project was funded by a pilot grant from the Dean's Office, Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R. conceived the project, conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. M.S. helped with the experiments and with data analysis and critical review of manuscript. J.M.G. provided input on project conception, analysis of results and manuscript development.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Info File #1

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rastogi, D., Suzuki, M. & Greally, J. Differential epigenome-wide DNA methylation patterns in childhood obesity-associated asthma. Sci Rep 3, 2164 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02164

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02164

This article is cited by

-

Epigenetic regulation of pediatric and neonatal immune responses

Pediatric Research (2022)

-

A review of epigenetic changes in asthma: methylation and acetylation

Clinical Epigenetics (2021)

-

Transcriptome analysis of peripheral whole blood identifies crucial lncRNAs implicated in childhood asthma

BMC Medical Genomics (2020)

-

The association of genetically controlled CpG methylation (cg158269415) of protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type N2 (PTPRN2) with childhood obesity

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Asthma, GERD and Obesity: Triangle of Inflammation

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.